Original Article

PROCESSING OF Ni-BASED SUPERALLOYS USING ENERGY-CONCENTRATED CAVITATION WITH HEAVY WATER AND SYNCHROTRON X-RAYS

INTRODUCTION

Hydrogen gas

turbines are a vital aspect of achieving a carbon-neutral society. Although

current systems operate on the principle of co-firing using 30% hydrogen in

natural gas, 100% hydrogen combustion is anticipated in the future. However,

turbine blades require further improvements in strength and service life to

allow operation at temperatures in excess of 1600 °C. Conventional Ni-based

superalloys containing rare metals have been widely used for this purpose but

new surface-modification technologies are needed due to concerns regarding cost

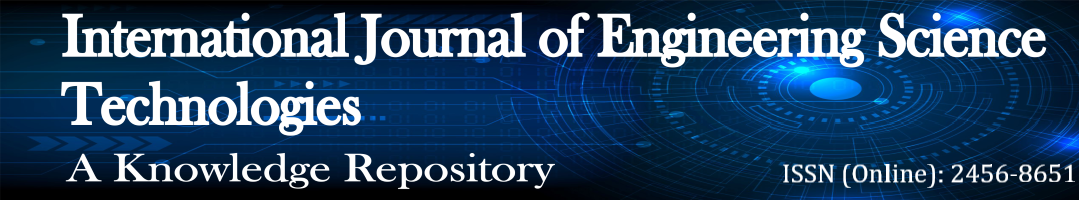

and structural stability. As shown in Figure 1, the authors previously

developed a focused energy multifunction cavitation (MFC) technique combining a

water jet, ultrasound, a magnetic field, laser irradiation, and a positron

source (PLMEI-MFC) Yoshimura

et al. (2023), Yoshimura

et al. (2024). When ultrasound is applied to this water

jet system, variations in acoustic pressure induce the repeated isothermal

expansion and adiabatic compression of air bubbles in the jet to produce high

temperatures and pressures within the bubbles Nagata

et al. (1992), Suslick

et al. (1991), Yeung et

al. (1993), Gompf et

al. (1997), Gendanken

et al. (2004). The microjets produced during bubble

collapse can generate extremes of heat and pressure capable of modifying the

surfaces of various material. This process is termed MFC because it can impart

advanced surface functionalities Yoshimura

et al. (2016), Yoshimura

et al. (2018a), Yoshimura

et al. (2018b), Yoshimura

et al. (2020). This technique was later modified by adding

synchrotron X-rays as a photoionization source Rack et al. (2008), Sun et al. (2022), Owen et al. (2016), Fengcheng

et al. (2024), resulting in the development of a

PXMEI‑MFC (Positron X‑ray Magnetic Energy Integration –

Multifunction Cavitation) system involving synchrotron irradiation Yoshimura

et al. (2025-3). This technology generates high temperatures

and pressures via the collapse of cavitation bubbles, enabling the

strengthening, cleaning, microstructural stabilization, and γ' phase

optimization of Ni-based superalloy surfaces. PXMEI-MFC using acetone or

deuterated acetone has demonstrated significantly increased bubble temperatures

and pressures, leading to the pronounced strengthening of SC610 alloy surfaces

together with the removal of oxide films Yoshimura

et al. (2025-3).

Heavy water

(D₂O) and non-deuterated water (H₂O) exhibit similar physical

properties yet differ in vapor pressure, viscosity, and bond energy, and so

would be expected to affect the temperatures and pressures associated with

cavitation collapse. Theoretically, D₂O should provide stronger adiabatic

compression, potentially generating higher temperatures and pressures. In the

present study, PXMEI-MFC was applied to the Ni-based superalloys SC610 and

CMSX-4 using either water or mixtures of water and heavy water. The goal of

this work was to determine whether the strengthening and self-organization

effects observed in systems using acetone or deuterated acetone can be

reproduced in aqueous systems. Additional aims were to clarify the manner in

which variations in the properties of the liquid medium affect cavitation

behavior and surface modification and to evaluate the role of photoionization

induced by synchrotron radiation.

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 A Summary of

Systems for Concentrating Energy in Cavitation Bubbles |

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The specimens used

in this study were second-generation Ni-based single-crystal superalloys

containing Re (SC610-SC and CMSX-4), both of which exhibit high creep strength

and excellent oxidation resistance. The chemical compositions of these

materials are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Each specimen had dimensions

of ⌀30 mm × 1 mm thickness and was buff-polished sequentially

using #80, #220, #500, #800, #1200, and #2000 abrasive papers followed by a

final polishing with an oxide suspension. Each specimen was subsequently

spot-welded to an electrode and electrolytically polished in a solution of 10%

hydrochloric acid and 90% methanol at 3 V DC for 60 s to reveal the

crystal structure. PXMEI-MFC processing of the specimens was conducted on the

BL09 beamline within the Kyushu Synchrotron Light Research Center.

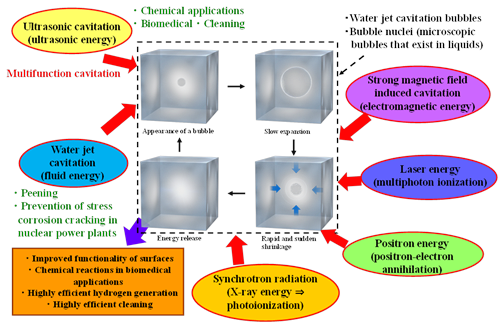

Figure 2(a)

shows the crystal structure of the Ni-based single-crystal superalloys used in

this study. These materials each contained an ordered γ' phase and a

disordered γ matrix. The γ' phase had an L1₂ structure based on

a face-centered cubic lattice, as shown in Figure 2(c). The alloys

employed in turbine rotor blades experience high temperatures and centrifugal

forces during use that can induce structural changes. As shown in

Figure 2(b), the γ' and γ phases in such metals align

perpendicular to the applied force vector. The resulting creep damage is known

as rafting, and elements such as Ta, W, and Re are added to Ni and Al to

stabilize the structure and suppress this phenomenon.

The pretreatment

of Ni-based superalloy turbine blades typically involves several steps. The

surface of each blade is first cleaned with solvents to remove contaminants

such as oils, following which the material is polished to eliminate fine

defects and remove impurities. The blade is subsequently immersed in a chemical

bath to remove surface oxides and contaminants, followed by heat treatment at a

specific temperature to stabilize the internal microstructure. The objective of

the work reported herein was to reproduce this complex pretreatment sequence

within a single process using the PXMEI-MFC system.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Chemical Composition

of the SC610-SC Alloy used in this Work (mass%) |

|||||||||

|

Cr |

Co |

Ni |

Mo |

Hf |

Ta |

W |

Re |

Al |

Nb |

|

7.4 |

1.0 |

Bal. |

0.6 |

0.1 |

8.8 |

7.2 |

1.4 |

5.0 |

1.7 |

Table 2

|

Table 2 Chemical Composition of the CMSX-4-SC Alloy Used in this work (mass%) |

|||||||||

|

Cr |

Co |

Ni |

Mo |

Hf |

Ta |

W |

Re |

Al |

Ti |

|

6.5 |

9 |

Bal. |

0.6 |

0.1 |

6.5 |

6 |

3 |

5.6 |

1 |

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 Diagrams Showing an Alloy Specimen (a) before and (b) After Rafting

and (c) a Diagram Showing the Crystal Structure of the γ' Phase (that

is, the L12 Structure) |

It is vital that a

Ni-based single-crystal superalloy has optimal proportions of the γ and

γ' phases. Specifically, a γ' volume fraction of approximately 70% is

considered ideal with regard to maximizing high-temperature performance Caccuri

et al. (2017), Yu et al. (2020). This composition enhances both creep

strength and structural stability at elevated temperatures. High-temperature

casting of these alloys also promotes the formation of a single-crystal

structure that improves strength and durability by eliminating grain

boundaries. Finally, it is known that controlling the proportion of the γ'

phase can maximize creep life. An overly high γ' volume fraction can

accelerate the collapse of the rafted structure, potentially reducing creep

life. Therefore, it is vital to maintain an appropriate ratio of the two

phases.

Ni-based

single-crystal superalloys are widely used in components exposed to the highest

temperatures in aircraft engines and industrial gas turbines, such as high- and

intermediate-pressure turbine blades, vanes, and shrouds. The widespread use of

these alloys is attributed to their exceptional mechanical properties at

temperatures up to approximately 1150 °C Caccuri

et al. (2017), Yu et al. (2020). These superior properties arise from the

absence of grain boundaries and the high proportion (approximately 70% in most

commercial alloys up to 800 °C) of strengthening γ' precipitates

with an L1₂ crystal structure coherently embedded within the disordered

face-centered cubic γ matrix Caccuri

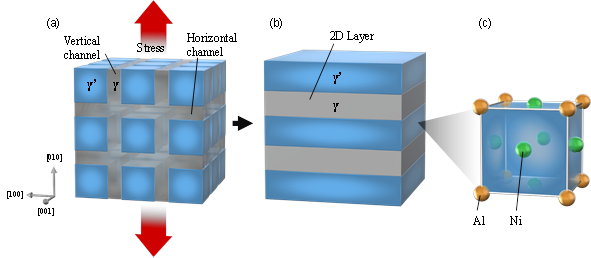

et al. (2017), Yu et al. (2020), Wang et al. (2025), Tan et al. (2025), Wang et al. (2024). Figure 3 presents a diagram of the reaction chamber used in this

study [16]. The chamber was filled with water containing 1.0% heavy water that

was discharged using a high-pressure pump providing a maximum pressure of

40 MPa and a maximum flow rate of 200 mL/min (L.TEX8731, L. TEX

Corporation). The high-pressure mixture of water and heavy water was injected

through a 0.2 mm nozzle installed at the center of the tank. The spray

pressure was measured using a pressure gauge while the flow rate was monitored using

a flowmeter attached to the pump. Although the nozzle of this apparatus is

typically made of SUS304 stainless steel, the nozzle employed in the present

study was fabricated from the Ni-based superalloy CM186LC to allow the unit to

withstand the severe processing environment. The spray pressure and flow rate

were 30 MPa and 195 mL/min, respectively. A 22Na positron source

was placed at the top of the tank to irradiate the water surface with positrons

and an acrylic lid was installed to prevent water escaping from the chamber.

The arrangement of the ultrasonic transducers and neodymium magnets was

equivalent to that described in previous reports [1,2]. A mixture of

non-deuterated water and heavy water was injected onto SC610 specimens having a

columnar-crystal morphology. As cavitation bubbles generated at the nozzle

collapsed, numerous new bubbles were formed and the specimen was positioned at

the location at which the cavitation cloud was most concentrated.

Five ultrasonic

transducers each having a frequency of 28 kHz (WSC28ST standard

oscillator and WSC28 integrated custom oscillator, Honda Electronics Company)

were placed around the cavitation jet to generate longitudinal acoustic

pressure waves. At low acoustic pressures, the bubbles underwent isothermal

expansion whereas at high acoustic pressures these bubbles rapidly contracted

and experienced adiabatic compression. Repetition of this process generated

extremely high temperatures inside the bubbles, enabling cavitation-based

processing. A total of 78 neodymium magnets was installed, comprising 39 at the

top of the chamber and 39 at the base. The top and bottom of the apparatus

corresponded to the north and south magnetic poles, respectively, with magnetic

field lines running from the lower right to the upper left of the device.

During MFC processing, charged bubbles were generated containing H⁺,

OH⁻, D⁺, and OD⁻ ions generated by thermal decomposition of

water vapor together with N+ ions penetrating through the bubble walls. These

charged bubbles collided with one another perpendicular to the flow direction

as they moved through the strong magnetic field in accordance with Fleming’s

rule. These collisions produced new high-temperature, high-pressure bubbles,

thereby enhancing the processing intensity.

In the case of

LMEI-MFC processing, laser light having a wavelength of 450 nm and output

power of 42.3 mW was imparted to the cavitation cloud to induce

multiphoton ionization inside the bubbles, increasing the ion charge states.

This irradiation strengthened the Coulomb interactions between bubbles,

resulting in more frequent bubble collisions and an increased number of

bubbles. However, because previous studies showed that laser irradiation

required processing times exceeding 30 min, high energy monochromatic

X-rays generated by synchrotron radiation were used instead of laser light in

the present work.

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 Diagram of the Apparatus

used for EI-MFC Processing in a Strong Magnetic Field Together with Synchrotron

X-Rays and Positron Excitation |

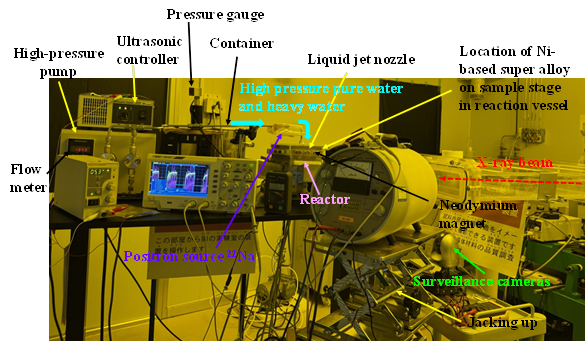

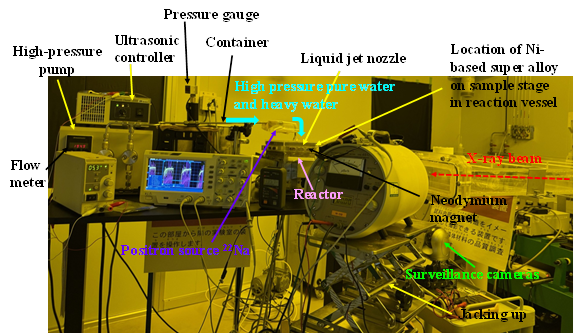

Figure 4 shows the installation of the PXMEI-MFC

system on the BL09 beamline at the Kyushu Synchrotron Light Research Center.

During these experiments, the BL09 beamline provided a high-flux monochromatic

X-ray beam with a uniform wavelength, a beam size of 8 mm (width) × 130 mm

(height), an energy of 8 keV, and a photon flux of 5×108 photons/s/mm² at 200

mA. To prevent beam loss during transmission through the surrounding air, a

rectangular acrylic introduction tube was installed, with its inlet and outlet

sealed by 0.05-mm-thick polymer films. This tube was filled with helium. Upon

irradiation of the MFC apparatus, positrons underwent partial annihilation

through interactions with electrons, producing gamma rays and releasing energy

via the reaction 𝑒+ + 𝑒− → 2𝛾 (1.02 MeV).

In previous studies using this system, a mixture of acetone and deuterated

acetone served as the liquid medium. In contrast, the present study employed a

mixture of 1% heavy water and 99% water to further increase the temperature and

pressure of the bubbles. This mixture was stored in a processing tank and

delivered using a high-pressure pump, and the distance between the nozzle and

the sample was set to 20 mm. A monochromatic X-ray beam with a height of 8 mm

and a width of 130 mm was directed perpendicularly onto the jet at a height of

5 mm above the sample surface.

|

Figure 4 Photographic Images Showing the

Installation of the PXMEI-MFC Device on The BL09 Beamline at the Kyushu

Synchrotron Light Research Center. (A) the Arrangement of the PXMEI-MFC

Experimental Apparatus Prior to X-Ray Irradiation, as Seen Inside the

Experimental Hutch, and (B) the PXMEI-MFC Apparatus During X-Ray Irradiation as

Seen from Outside the Experimental Hutch |

EXPERIMENT RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

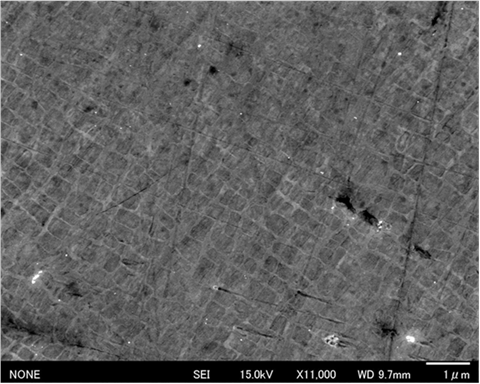

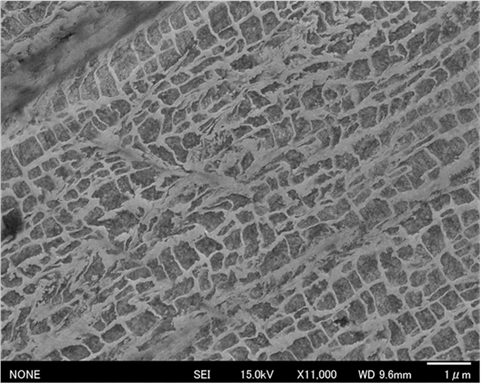

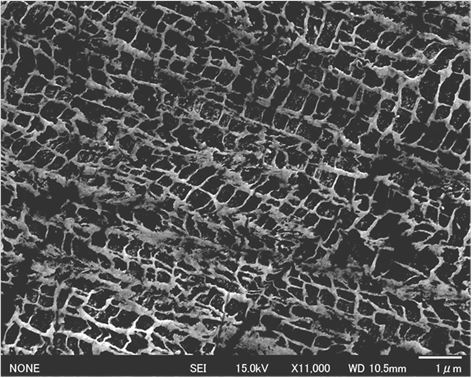

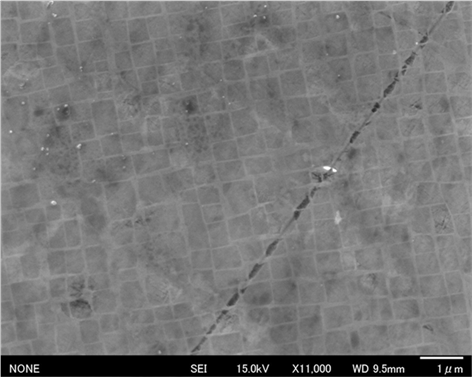

Figures 5 and Figure 6 provide scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

images of the central surface regions of SC610 specimens processed for 20 min

using the PXMEI-MFC system with water and with a mixture of water and heavy

water, respectively. When using water as the liquid medium, the lattice

structure of the metal was not affected even after the relatively long

processing time of 20 min. In contrast, the incorporation of heavy water led to

significant disruption of the lattice despite the low heavy water concentration

of 1%. It is also apparent from Figure 6 that the γ′ phase was removed to

a greater extent than the γ phase.

Prior work using a

mixture of acetone and deuterated acetone gave the desired γ′ phase

proportion of 70% as a result of self-organization of the alloy, which was not

achieved in the present work. In the case of the acetone/deuterated acetone system,

the balance of various energies tended to improve the properties of the SC610

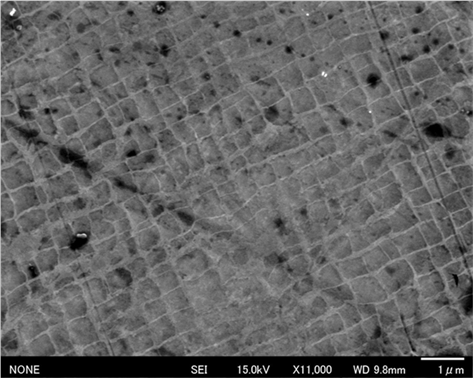

and a high-strength surface was formed through self-organization. Figure 7 shows an SEM image of the region surrounding

the jet center shown in Figure 6. It can be seen that the lattice structure

was disrupted even in this peripheral area and that the γ′ phase was

stripped away to a significant depth. Theoretically, it should be possible to

induce self-organization of the SC610 surface and to increase the strength of

the alloy even when using non-deuterated water. This might require a processing

duration that allows diffusion and rearrangement of the alloy atoms to occur

near the surface before the γ′ phase is destroyed, to promote

self-organization of this phase and give the desired proportion of

approximately 70%. To achieve this, the excess energy imparted to the surface

must be suppressed by reducing both the pressure and flow rate. Because SC610

exhibits high strength and a large proportion of the γ′ phase, the

application of an excessive impact force leads to the destruction of this

phase. Therefore, lowering the water-jet discharge pressure and carefully

adjusting the flow rate could prevent damage to this phase while promoting

structural ordering.

Figure 5

|

Figure 5 SEM Image of the Central

Surface of an SC610 Specimen Processed for 20 Min Using the PXMEI-MFC System

with Non-Deuterated Water |

Figure 6

|

Figure 6 SEM Image of the Central Surface of an

SC610 Specimen Processed For 20 Min Using the PXMEI-MFC System with a Mixture

of Non-Deuterated and Heavy Water |

Figure 7

|

Figure 7 SEM Image of the

Surface Around the Processed area of the SC610 Specimen Shown in Figure 6 |

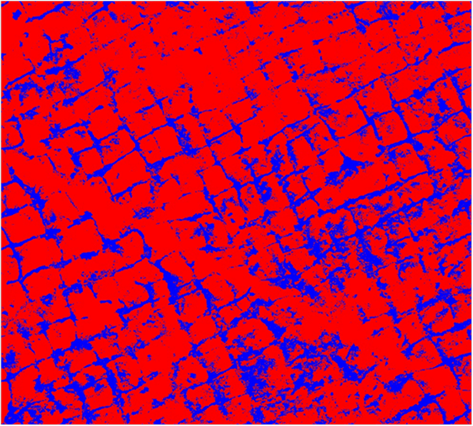

Figure 8 shows an SEM image of a CMSX-4 specimen

prior to processing with the PXMEI-MFC apparatus. It is evident that the

γ′ and γ phases were arranged in an orderly manner in this

material. Figure 9 presents an SEM image of the region of this

sample on which the jet impact was centered after 10 min of processing by

PXMEI-MFC using a mixture of non-deuterated and heavy water. Although the

γ phase lattice structure exhibits only slight disturbance, etching of the

γ′ phase can be observed, similar to the results shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7. Figure 10 shows the binarized version of the SEM image

in Figure 9. The γ′phase, indicated in red,

accounts for 79% of the image area while the γ phase, indicated in blue,

comprises 21% of the total area. In contrast, a mixture of acetone and

deuterated acetone previously demonstrated surface strengthening as a result of

self-organization to give a γ′ phase proportion of approximately 70%

over a wide region. As noted, this is the optimal proportion of this phase with

regard to achieving the highest possible strength. On this basis, it is evidently

necessary to identify an energy input that provides the appropriate extent of

atomic diffusion and reduces the amount of γ′ phase relative to the

result shown in Figure 9.

Figure 8

|

Figure 8 SEM Image Of A CMSX-4 Specimen Prior To

Processing By PXMEI-MFC |

Figure 9

|

Figure 9 SEM Image of the

Center of a CMSX-4 Specimen after 10 min of PXMEI-MFC Processing with a

Mixture of Non-Deuterated and Heavy Water |

Figure 10

|

Figure 10 Binarized Version

of the SEM Image Shown in Figure 9. The γ' Phase is Shown in red and

Comprises 79% of the Specimen while the γ Phase is Shown in Blue and

Comprises 21% |

Figure 11 provides a laser microscopy image showing

the surface of a sample of the Ni-based single-crystal superalloy CM186LC-DS

after 10 min of PXMEI-MFC processing using a mixture of acetone and deuterated

acetone. A rafting microstructure in which the γ and γ' phases are

aligned parallel to one another near the central depression can be observed. It

should be noted that rafting does not occur simply as a consequence of a high

energy input. Rather, this phenomenon requires a unidirectional stress field

together with sufficient atomic diffusion over an appropriate time scale, and a

suitable lattice misfit. The system comprising a mixture of water and heavy

water provided high bubble collapse energies but generated a highly disordered

and excessive stress field, such that the surface reactions and the dissolution

of the alloy were intensified. As a result, rafting did not occur but the

γ' phase was damaged and selectively removed. Rafting typically occurs in

Ni-based superalloys in response to conditions that promote creep or thermal

fatigue. The signs and magnitudes of the γ/γ' phase elastic misfit,

the direction of the external stress (whether tensile or compressive), and the

temperature/time scale (as required to allow sufficient diffusion) determine

whether the γ' phase connects along the stress direction to form a rafted

structure, meaning a plate-like arrangement in which γ and γ' phases

align parallel to one another. Thus, rafting is not driven by high-energy

impacts but by the formation of a directional, quasi-static stress field

combined with diffusion-mediated phase rearrangement.

An

acetone/deuterated acetone mixture has a lower surface tension than water or

heavy water together with a higher vapor pressure. These factors suppress

asymmetric bubble deformation during collapse, leading to collapse modes that

generate sharp microjets that are less likely to appear in aqueous systems.

Consequently, the stresses imparted near the specimen by bubble collapse tend

to be more homogeneous and quasi-steady in a time-averaged sense.

The occurrence of

rafting in the CM186LC specimen and the formation of a self-organized γ'

phase having a proportion of 70% in the SC610 alloy can be attributed to the

different energy relaxation pathways arising from alloy-specific

characteristics. These characteristics include the initial γ/γ'

misfit and the γ' proportion together with the creep strength and

deformability of the alloy. In the case of the CM186LC, these conditions favor

the formation of a weakly oriented rafted structure, whereas the same conditions

promote more uniform self-organization and the formation of an optimal 70%

proportion of the γ' phase in the higher-strength SC610 alloy.

The mixture of

water and heavy water provided higher bubble collapse energies but the

resulting microstructures exhibited lattice disorder, selective removal of the

γ' phase, and the absence of a rafted structure. Hence, increasing the

energy input did not promote rafting but instead degraded the alloy’s lattice

structure and enhanced dissolution of the metal. It is possible to suggest a

mechanism whereby an excessive energy input prevents rafting. In this

mechanism, the stress field becomes highly random and overly intense, thus

losing the directionality required for rafting. High-energy aqueous cavitation

produces bubble collapses with highly random positions and orientations such

that shock waves and microjets impinge on the alloy from multiple directions.

As a result, the local stresses are large but lack directionality and also

occur in the form of numerous extremely short pulses. This phenomenon resembles

a collection of high-speed impacts rather than a creep-like stress field. Under

such conditions, the γ' phase does not align directionally and localized

shear forces occur along with the formation of defects, lattice decomposition,

and alloy dissolution. In the case of the system using a mixture of water and

heavy water, interfacial dissolution and chemical reactions will be more

important than diffusion-driven ordering. The cavitation in this process will

generate radicals that react with dissolved oxygen while localized zones of

high temperature and pressure will promote oxidation and dissolution to a greater

degree compared with acetone-based systems. Because the γ' phase contains

significant amounts of Al, Ti, and Ta in addition to Ni, the chemical

properties of this material differ from those of the γ phase, making

selective dissolution or degradation possible. The observed lattice disorder

and selective removal of the γ' phase indicate that surface/interface

destruction and dissolution occurred rather than the microscopic-scale

diffusion-driven ordering required for rafting.

Figure 11

|

Figure 11 Laser Microscopy

Image of the Surface of a NI-Based Superalloy CM186LC-DS Specimen After 10

Min Of PXMEI-MFC Processing Using a Mixture of Acetone and Heavy Acetone |

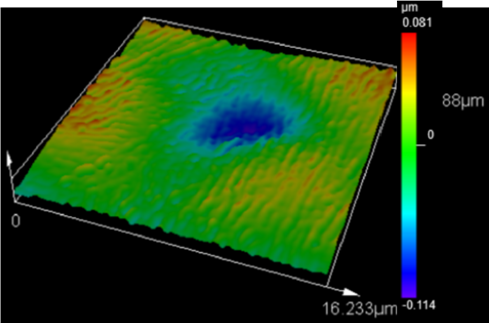

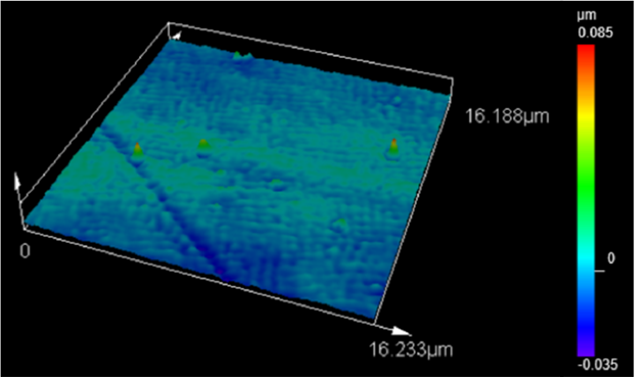

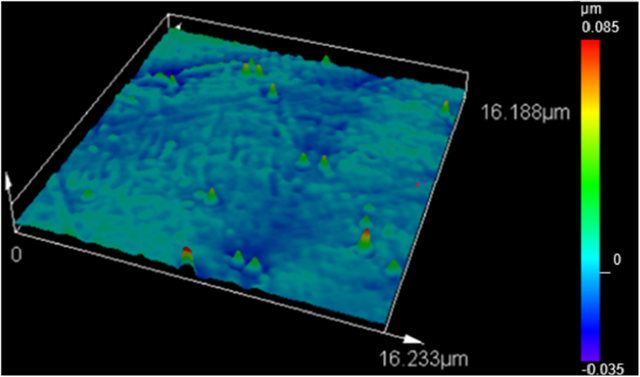

Figure 12 shows a laser microscopy image acquired before 10 min of processing

with the PXMEI-MFC apparatus using a mixture of water and heavy water. Similar

to the SEM image obtained prior to processing, a lattice structure composed of

the γ' and γ phases is apparent. After processing, slight distortions

of the lattice structure and localized surface irregularities appear. The

arithmetic mean roughness values before processing (Ra: 0.003 μm, Sa:

0.004 μm) were increased to 0.019 μm and 0.007 μm, respectively,

after processing Figure 13. However, the surface flattening observed

when using a mixture of acetone and heavy acetone was not observed.

Figure 12

|

Figure 12 Laser Microscopy

Image of a CMSX-4 Specimen Prior to PXMEI-MFC Processing |

Figure 13

|

Figure 13 Laser Microscopy

Image of the Specimen Shown in Figure 12 After 10 Min Of PXMEI-MFC Processing

Using a Mixture of Water and Heavy Water |

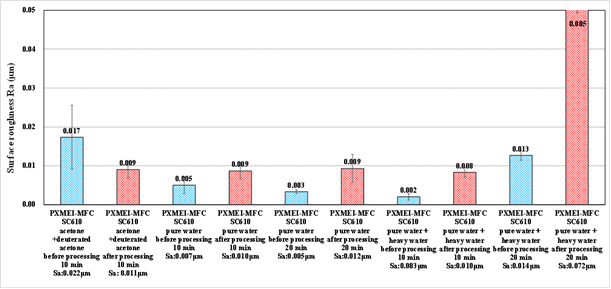

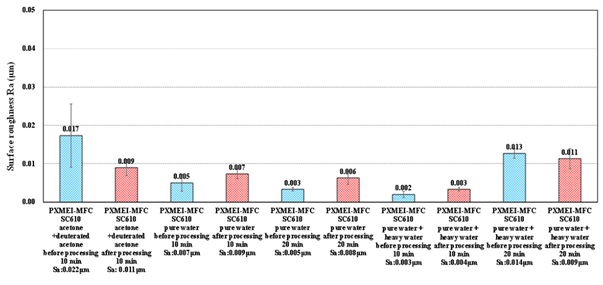

Figure 14 summarizes the surface roughness values

found by laser microscopy at the centers of the processed areas of SC610

specimens treated with the PXMEI-MFC technique under various conditions. A

mixture of acetone and heavy acetone decreased the initial arithmetic mean

surface roughness, Ra, of 0.017 μm and arithmetic mean height, Sa, of

0.022 μm to 0.009 μm and 0.011 μm, respectively, indicating that

the surface was flattened. In contrast, when a mixture of water and heavy water

was used, the surface roughness was instead increased after processing under

all conditions. In particular, 20 min of processing with water and heavy water

increased the initial values of Ra = 0.013 μm and Sa = 0.014 μm to

0.085 μm and 0.072 μm, respectively. These results suggest that

microjets generated by cavitation and containing heavy water generated higher

impact pressures.

Figure 15 summarizes the surface roughness values

determined by laser microscopy around the periphery of the treated areas of

SC610 specimens processed under various PXMEI-MFC conditions. Compared with the

centers, the overall roughness values for these regions were lower. While the

acetone/heavy acetone mixture produced a uniform surface, the water/heavy water

combination evidently resulted in a spatial distribution of roughness. Notably,

following 20 min of processing with a mixture of water and heavy water, the center

region exhibited a sharp increase in Ra from 0.013 μm before processing to

0.085 μm after processing, whereas the peripheral region showed a decrease

from Ra = 0.013 μm to Ra = 0.011 μm.

Figure 14

|

Figure 14 Surface Roughness

Values at the Centers of Specimens of the NI-Based Superalloy SC610 After

PXMEI-MFC Processing Under Various Conditions as Determined by Laser

Microscopy |

Figure 15

|

Figure 15 Surface Roughness Values at the Peripheral

Areas of Specimens of the NI-based Superalloy SC610 After PXMEI-MFC

Processing Under Various Conditions as Determined by Laser Microscopy |

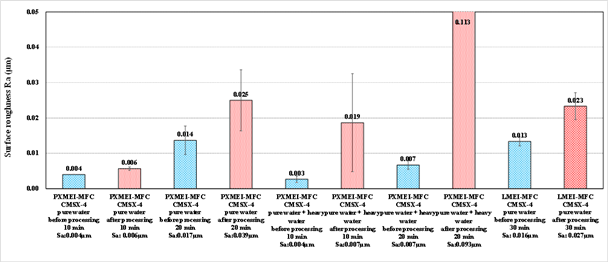

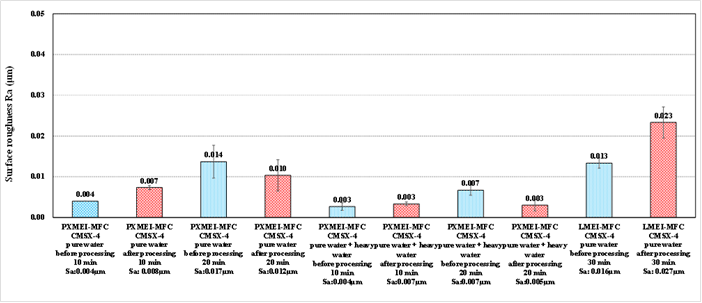

Figures 16 and 17

show the surface roughness values at the centers and peripheral regions,

respectively, of CMSX-4 samples processed under various PXMEI-MFC conditions.

In all cases, the surface roughness was increased after processing. A 20 min

treatment using a mixture of water and heavy water provided a maximum value of

Ra = 0.113 μm at the center that exceeded the value obtained by LMEI-MFC

processing for 30 min. In contrast, within the peripheral region, the roughness

decreased from Ra = 0.007 μm before processing to Ra = 0.003 μm after

processing, indicating surface flattening. This outcome suggests that the

cavitation energy was concentrated at the center of processing, whereas the

energy in the peripheral region was at a level more suitable for surface

smoothing.

Figure 16

|

Figure 16 Surface Roughness

Values at the Centers of Specimens of the Ni-Based Superalloy CMSX-4 after

PXMEI-MFC or LMEI-MFC Processing Under Various Conditions as Determined by Laser

Microscopy |

Figure 17

|

Figure 17 Surface Roughness values at the Peripheral Areas of Specimens of the

Ni-Based Superalloy CMSX-4 after PXMEI-MFC or LMEI-MFC Processing Under

Various Conditions as Determined by Laser Microscopy |

Specimens were

characterized by SEM (JEOL Ltd., JSM-7000F) and energy-dispersive X-ray

spectroscopy (EDS; Oxford Instruments, X-Max series) before and after

processing. When PXMEI-MFC processing was performed using a mixture of acetone

and heavy acetone, the microstructure-stabilizing elements Ta, W, and Re were

found to diffuse toward the surface and to segregate. In the present

experiments using the water/heavy water system, slight surface segregation of

Ta was observed in the SC610 specimens at both the jet center and the

peripheral regions, while a small extent of W segregation was evident in the

CMSX-4 alloy.

Exposure to X-rays

can induce both photoionization and radiolysis inside cavitation bubbles,

leading to the reduction of oxide films by hydrated electrons (Eaq–) and

reducing radicals such as H·. However, the EDS results showed no significant

change in the oxygen content of the metal after processing, indicating that the

oxide film had not been removed, even though such removal was observed in

trials using an acetone/heavy acetone mixture. This finding suggests that the

balance of applied energies was insufficient to induce photoionization or

radiolysis. The high water-jet pressure of 30 MPa used in this study produced

an extremely high flow velocity, shortening the bubble residence time and the

interfacial interaction time. As such, reactive species were likely to

disappear before reaching the surface of the metal. Because the radiolysis

yield of water or heavy water depends on the absorbed dose and linear energy

transfer, reducing the jet pressure while increasing the X-ray intensity could

possibly provide better results.

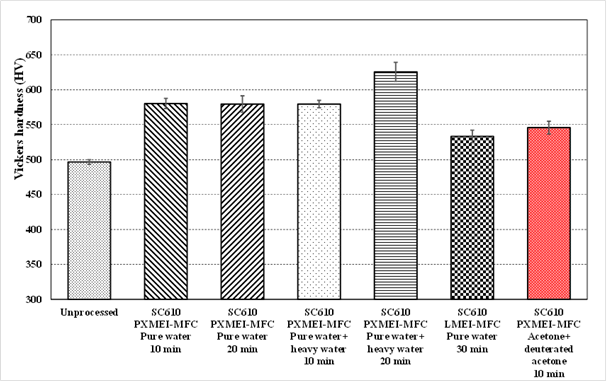

This study

originally intended to investigate the compressive residual stresses imparted

to alloy surfaces. However, the crystal structures of the Ni-based superalloys

could not be confirmed using an X-ray residual stress measurement system. As an

alternative, surface hardness data were obtained using a micro-Vickers hardness

tester after various cavitation treatments. Because the size of the processed

region was limited when using the mixture of water and heavy water, the entire

specimen surface was first observed by low-magnification laser microscopy,

followed by a high-magnification observation of the processed area. The

observation region was then designated using a permanent marker and

micro-Vickers hardness measurements were performed within this region. The

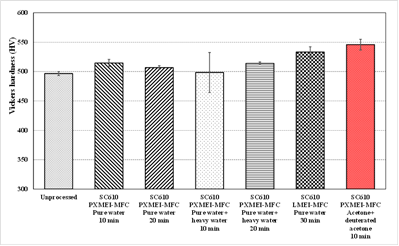

results for the SC610 and CMSX-4 specimens are summarized in Figure 18 (jet center), Figure 19 (jet periphery), Figure 20 (jet center), and Figure 21 (jet periphery), respectively.

In the case of the

SC610 alloy, both 10 and 20 min trials using water resulted in a hardness

increase of approximately 80 HV, indicating that varying the processing

duration had no significant effect. A 10 min treatment with heavy water also

produced an increase of about 80 HV. However, this result may have been

influenced by the experimental sequence. In the trial in which the SC610 sample

was processed using heavy water for 10 min, 24 L of water and 200 mL of heavy

water were added to the tank, whereas only non-deuterated water was present in

the reaction chamber. In contrast, the 20 min experiment involving the SC610

alloy was conducted following a 10 min treatment of a CMSX-4 specimen with

heavy water, meaning that the reaction chamber already contained a mixture of

water and heavy water. As a result, the cavitation generated during the 20 min

processing trial involved a greater concentration of heavy water. Treatment of

the SC610 with heavy water for 20 min in this manner produced a hardness

increase of 130 HV, demonstrating that cavitation in a medium incorporating

heavy water at even a low concentration had a greater effect on the alloy. This

outcome suggests that the cavitation collapse pressure was increased in the

presence of heavy water.

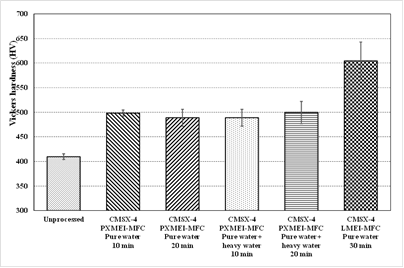

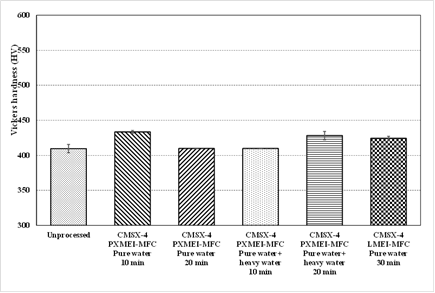

The CMSX-4

specimens exhibited hardness increases ranging from 70 to 90 HV regardless of

the processing time (either 10 or 20 min) or the presence of heavy water.

Treatment using the LMEI-MFC apparatus involving laser irradiation produced the

highest hardness increase of approximately 200 HV. As shown in Figure 16, a Figure 20 min processing trial using the water/heavy

water system resulted in significant lattice destruction and a drastic increase

in surface roughness. Conversely, the lattice structure composed of γ' and

γ phases was preserved after 30 min of LMEI-MFC processing, resulting in

higher hardness.

Figure 18

|

Figure 18 Vickers Hardness Values at The Processing

Centers of Specimensof the NI-Based Superalloy SC610 After Processing by

PXMEI-MFC Or LMEI-MFC Under Various Conditions |

Figure 19

|

Figure 19 Vickers Hardness Values

at the Peripheral areas of Specimens of the NI-Based Superalloy SC610 after

Processing by PXMEI-MFC or LMEI-MFC Under Various Conditions |

Fiugre 20

|

Figure 20 Vickers Hardness Values at the Processing

Centers of Specimens of the NI-Based Superalloy CMSX-4 after Processing by

PXMEI-MFC or LMEI-MFC Under Various Conditions |

Figure 21

|

Figure 21 Vickers Hardness

Values at the Peripheral Areas of Specimens of the NI-Based Superalloy CMSX-4

After Processing By PXMEI-MFC Or LMEI-MFC Under Various Conditions |

CONCLUSIONS

A PXMEI-MFC system

incorporating X-ray irradiation from a synchrotron facility was used to process

samples of the Ni-based superalloys SC610 and CMSX-4 with a mixture of water

and heavy water. In previous work, processing with a mixture of acetone and heavy

acetone enabled uniform treatment across the entire specimen. Processing with

the present combination of water and heavy water resulted in higher hardness

compared with values obtained using the acetone/heavy acetone mixture but over

a smaller area. Moreover, no significant surface segregation of Ta, W, or Re,

all elements that stabilize the lattice structure, was observed. Interestingly,

the addition of even a small proportion of heavy water to the non-deuterated

water increased the processing capability of the system. Self-organization of

the alloy leading to the formation of a high-strength γ' phase in the

ideal proportion of 70% did not occur and the lattice structure of the metal

showed both deformation and degradation. Consequently, the single-crystal

Ni-based superalloys specimens were not strengthened. To prevent destruction of

the γ' phase, it will be necessary to reduce the jet pressure and flow

rate to lower the energy input. Because heavy water increases the degree of

metal processing to a significant extent at a given jet pressure, the injection

pressure must be lowered accordingly.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are

grateful to Dr. Kotaro Ishiji of the SAGA Light Source facility for providing

invaluable technical assistance and insightful contributions to this research.

Dr. Ishiji’s expertise and dedication were instrumental in the successful

completion of this study.

REFERENCES

Caccuri, V., Cormier, J., and Desmorat, R. (2017). γ′-Rafting Mechanisms under Complex Mechanical Stress state in Ni-Based Single Crystalline Superalloys. Materials & Design,131, 7-497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2017.06.018

Fengcheng, L., Runze, L., Wenjun, L., Mingyuan, X., and Song, Q. (2024). Synchrotron Radiation: A Key Tool for Drug Discovery. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 114(1), 29990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2024.129990

Gendanken, A. (2004). Using sonochemistry for the fabrication of nanomaterials. Ultrason. Sonochem., 11 (2), 47–55. 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2004.01.037

Gompf, B., Gunther, R., Nick, G., Pecha, R., and Eisenmenger, W. (1997). Resolving sonoluminescence pulse width with time-correlated single photon counting. Phys. Rev. Lett., 79, 1405-1408. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.79.1405

Nagata, Y., Watanabe, Y., Fujita, S., Dohmaru, T., Taniguchi, S. (1992). Formation of colloidal silver in water by ultrasonic irradiation. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun., 21, 1620–1622. https://doi.org/10.1039/C39920001620

Owen, R. L., Juanhuix, J., and Fuchs, M. (2016). Current advances in synchrotron radiation instrumentation for MX experiments. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 602(15), 21-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2016.03.021

Rack, A., Zabler, S., Müller, B. R., Riesemeier, H., Weidemann, G., Lange, A., Goebbels, J., Hentschel, M., and Görner, W. (2008). High resolution synchrotron-based radiography and tomography using hard X-rays at the BAMline (BESSY II). Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment, 586(2), 327-344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2007.11.020

Sun, R., Wang, Y., Zhang, J., Deng, T., Yi, Q., Yu, B., Huang, M., Li, G., and Jiang, X. (2022). Synchrotron radiation X-ray imaging with large field of view and high resolution using micro-scanning method. Journal of Synchrotron Radiation, 1241–1250.

Suslick, K. S., Choe, S. B., Cichowlas, A. A., and Grinstaff, M. W. (1991). Sonochemical synthesis of amorphous iron. Nature, 354, 414–416. https://doi.org/10.1038/353414a0

Tan, L., Yang, X. G., D.Q. Shi, W.Q. Huang, Lyu, S. Q., and Fan, Y. S. (2025). Effect of Microstructure Rafting on Deformation Behaviour and Crack Mechanism During High-Temperature Low-Cycle Fatigue of a Ni-Based Single Crystal Superalloy. International Journal of Fatigue, 190(1086199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2024.108619

Wang, P., Wen, Z., Li, M., Lu, G., Cheng, H., He, P., and Yue, Z. (2024). Modified crystal plasticity constitutive model considering tensorial properties of microstructural evolution and creep life prediction model for Ni-based single crystal superalloy with film cooling hole. International Journal of Plasticity, 183(104150). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijplas.2024.104150

Wang, R., You, W., Zhang, B., Li, M., Zhao, Y., Liu, H., Chen, G., Mi, D., Hu, D. (2025). Constitutive modeling of creep behavior considering microstructure evolution for directionally solidified nickel-based superalloys. Materials Science and Engineering: A 919, 147499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2024.147499

Yeung, S., Hobson, T., Biggs, S., and Grieser, F. (1993). Formation of Gold Sols Using Ultrasound. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun., 4, 378–379. https://doi.org/10.1039/C39930000378

Yoshimura, T., (Inventor). (2020). Assignee: Sanyo-Onoda City public university, Patent no. US, 10(590), 966 B2, Date of Patent, Method for Generating Mechanical and Electrochemical Cavitation, Method for Changing Geometric Shape and Electrochemical Properties of Substance Surface, Method for Peeling off Rare Metal, Mechanical and Electrochemical Cavitation Generator, and Method for Generating Nuclear Fusion Reaction of Deuterium. International PCT Pub. No.: W02016/136656, Pet Care Trust. No: PCT/JP2016/055016

Yoshimura, T., Maeda, Y., and Ito, S. (2025-3). Development of processing technology for Ni-based superalloys using energy-concentrated cavitation with synchrotron X-rays. Results in Materials, SSRN prerelease. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5185563

Yoshimura, T., Tanaka, K., and Ijiri, M. (2018b). Nanolevel Surface processing of fine particles by waterjet cavitation and multifunction cavitation to improve the photocatalytic properties of titanium oxide. Intech open access, Open Access Peer-reviewed Chapter 4, Cavitation - Selected Issues, 43-72. http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.79530

Yoshimura, T., Tanaka, K., and Yoshinaga, N. (2016). Development of Mechanical-Electrochemical Cavitation Technology. Journal of Jet Flow Eng., 32(1), 10-17, http://id.ndl.go.jp/bib/027265536

Yoshimura, T., Tanaka, K., and Yoshinaga, N. (2018a). Nano-level material processing by multifunction cavitation. Nanoscience & Nanotechnology-Asia, 8(1), 41-54. 10.2174/2210681206666160922164202

Yoshimura, T., Yamamoto, S., and Watanabe, H. (2023). Precise peening of Cr–Mo steel using energy- intensive multifunction cavitation in conjunction with a narrow nozzle and positron irradiation. Results in Materials 20(100463) 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinma.2023.100463

Yoshimura, T., Yamamoto, S., and Watanabe, H. (2024). Precise peening of Ni-Cr-Mo steel by energy-intensive multifunction cavitation in conjunction with positron irradiation. International Journal of Engineering Science Technologies, 8(2), 1–16.

Yu, Z., Wang, X., Yang, F., Yue, Z., James C., and Li, M. (2020). Review of γ’ Rafting Behavior inNickel-Based Superalloys: Crystal Plasticity and Phase-Field Simulation. Crystals, 10, (2020)1095. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst10121095

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© Granthaalayah 2014-2026. All Rights Reserved.