Original Article

Nominal Immiserizing Growth: Technological Progress, Deflation, and Foreign Currency Accumulation

|

Yasunori Fujita

1* 1 Keio University, Japan |

|

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

This paper develops a simple domestic macroeconomic model to examine how technological progress can generate immiserizing growth in nominal terms. While productivity improvements typically raise real output, the model shows that technological progress may sharply reduce prices when the price elasticity of demand is sufficiently low. As a result, the GDP deflator declines and nominal GDP falls over time despite continuous growth in real output. The analysis further demonstrates that declining nominal income leads to an expansion of foreign currency transactions, as domestic expenditure on goods decreases. By explicitly focusing on nominal GDP and price dynamics rather than real output alone, this paper provides a new interpretation of immiserizing growth and highlights an overlooked channel linking technological progress, deflation, and foreign currency accumulation. Keywords: Immiserizing Growth, Domestic Macroeconomy, Technological Progress,

Nominal GDP, Foreign Currency |

||

INTRODUCTION

Technological

progress is typically regarded as a fundamental source of economic growth and

improved living standards. In standard growth models, productivity improvements

raise real output and consumption, thereby enhancing social welfare. However, a

long-standing tradition in international economics has emphasized that economic

growth need not be unambiguously beneficial when it induces adverse price

movements. The seminal contribution by Bhagwati

et al. (1958) shows that growth can reduce welfare if it leads to a sufficiently

large deterioration in relative prices, a phenomenon known as immiserizing growth.

Closely related to

this insight is the observation that changes in relative prices generate a

wedge between production-based measures of output and income-based indicators.

In open economies, real GDP does not necessarily capture changes in purchasing

power when export and import prices move. Kohli et

al. (2004) demonstrates that real domestic income may

diverge substantially from real GDP due to terms-of-trade effects, while Kehoe

and Ruhl (2008) and Reinsdorf

et al. (2010) emphasize central role of deflators in

shaping both real and nominal income dynamics. These studies suggest that price

movements are not merely a secondary feature of growth but can fundamentally

alter the interpretation of macroeconomic performance.

A further strand

of research focuses specifically on the accumulation of foreign exchange

reserves and official foreign assets. Aizenman and

Lee (2007) distinguish precautionary motives from

mercantilist motives, while policy-oriented studies by the International Monetary Fund. (2011) and the European

Central Bank. (2006) highlight the macroeconomic costs of

sustained reserve accumulation, particularly under sterilized intervention.

More recently, Adler et

al. (2019) document systematic patterns of foreign

exchange intervention and show how such policies affect inflation and monetary

conditions. These contributions indicate that rising foreign currency holdings

may coexist with disinflationary or deflationary pressures. At the same time,

modern macroeconomic research has increasingly linked technological progress

and globalization to persistently low inflation. Studies such as Gopinath

et al. (2015) and Forbes

et al. (2019) argue that global competition and

technological innovation weaken pricing power and flatten Phillips curves,

generating sustained downward pressure on prices.

Despite these

advances, most existing studies focus primarily on real variables—such as real

GDP, productivity, or welfare—and treat nominal aggregates as secondary. In

particular, mechanism through which technological progress lowers the GDP

deflator, thereby reducing nominal GDP even as real output expands, has

received relatively little attention in formal dynamic models. Moreover,

interaction between deflationary price dynamics and accumulation of foreign

assets has not been fully explored in a parsimonious theoretical framework.

This paper

contributes to the literature by extending Fujita

et al. (2025) and developing a simple domestic

macroeconomic model that explicitly incorporates foreign currency transactions.

The model abstracts from goods trade and instead focuses on interaction between

technological progress, price formation, nominal income, and foreign currency

purchases. We show that when the price elasticity of demand is sufficiently

low, technological progress leads to a sharp decline in prices, causing nominal

GDP to fall over time even as real output grows. At the same time, trading

volume of foreign currency increases as nominal income is reallocated away from

domestic goods expenditure. This mechanism provides a new interpretation of immiserizing growth in nominal terms.

The remainder of

the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the basic model. Section

3 analyzes the conditions under which technological

progress generates immiserizing growth and increased

foreign currency transactions. Section 4 concludes.

BASIC MODEL

Let us consider a

domestic macroeconomic economy in which goods and foreign currency are traded

using money. Let Y(t), F(t), and M(t) denote the transaction volume of goods,

foreign currency purchases in domestic currency terms, and money supply in

period t, respectively.

We assume that

foreign currency is only purchased and not sold during the periods under

consideration. This assumption captures a situation in which households and

firms accumulate foreign assets as a store of value under persistent domestic

price declines. In addition, output produced in period t-1 constitutes income

in period t. Let P(t) denote the price of goods in period t. Then, total income

in period t, which is equal to the money supply M(t), is given by

![]()

This formulation

relies on the principle of three-sided equivalence, according to which

production GDP equals distribution GDP.

We further assume

that total income in period t, M(t), is fully spent on goods and foreign

currency purchases within the same period. Since expenditure on goods in period

tis P(t)Y(t) and expenditure on foreign currency in domestic currency terms is

F(t), budget constraint in period t is expressed as

![]()

Demand for goods

in period t is assumed to increase with disposable income net of foreign

currency purchases, M(t)-F(t), and to decrease with the price level P(t).

Accordingly, demand function for goods, Y^D (t), is specified as

![]()

where A is a

positive constant, ε is a positive constant that expresses price

elasticity of demand, and c is a marginal propensity to consume that satisfies

0<c<1.

On the supply

side, output grows at a constant rate g due to technological progress. Letting

Y_0 denote initial output, supply of goods in period t, Y^S (t), is given by

![]()

We assume full

employment and market clearing in every period, so that goods demand equals

goods supply, Y^D (t)=Y^S (t)=Y(t). Therefore, the equilibrium condition is

written as

![]()

Technological progress, immiserizing growth and trading volume of foreign currency

We are now ready

to derive the condition under which the economy in this paper exhibits immiserizing growth.

First,

substituting equation (2) into equation (5) and rearranging terms yield

![]()

Since the

left-hand side of equation (6) represents nominal GDP in period t, it follows

that nominal GDP is negatively related to P(t)^(ε-1)-c. Specifically, if

P(t)^(ε-1)-c increases over time, nominal GDP decreases, whereas if

P(t)^(ε-1)-c decreases over time, nominal GDP increases.

Equation (6) can

also be rewritten to determine the price level P(t) as

![]()

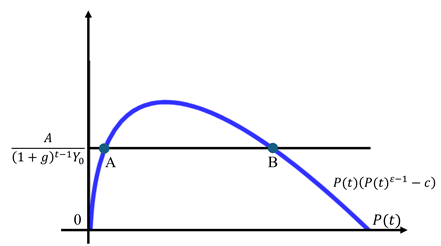

When ε<1,

Figure 1(i) illustrates that equation (7) admits two

solutions for P(t), denoted by points A and B. Let the right-hand side of

equation (7) be denoted by R. Taking the total differential of equation (7), we

obtain

![]()

At point A, the

condition εP(t)^(ε-1)-c>0 holds. Hence,

a small increase in the price raises the left-hand side of equation (8),

implying that P(t) must decrease to restore equality. This confirms that point

A is a stable equilibrium.

In contrast, at

point B, the condition εP(t)^(ε-1)-c<0

holds. In this case, a small increase in the price lowers the left-hand side of

equation (8), implying that P(t) must increase further to satisfy the equation.

Therefore, point B is an unstable equilibrium.

In what follows,

we focus on the stable equilibrium at point A and adopt it as the equilibrium

price level.

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 (a) Determination

of the Equilibrium Price P(t)when ε<1 |

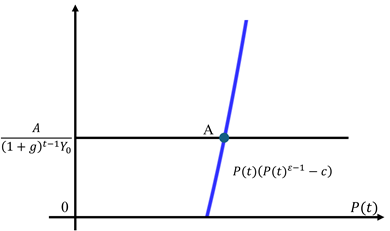

In contrast, when

ε>1, Figure 1(ii) shows that P(t) is uniquely determined at point A and

exhibits stable behavior.

|

Figure 1 (b)

Determination of the Equilibrium Price P(t)when ε>1 |

Since ![]() decreases over time, from Figures 1(i) and 1(ii), we obtain the

following Lemma 1.

decreases over time, from Figures 1(i) and 1(ii), we obtain the

following Lemma 1.

Lemma 1.

Suppose that the

supply of goods grows over time due to technological progress.

Regardless of

whether ε<1or ε>1, the equilibrium price P(t) decreases

monotonically over time.

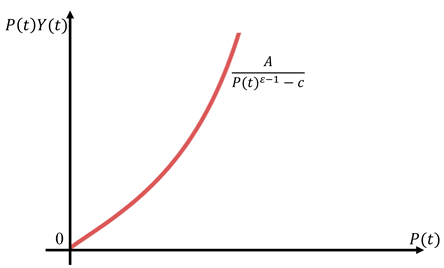

Graph of (6), on

the other hand, is depicted as an increasing curve as in Figure 2(i) if ε<1.

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 (a) Dynamics of Nominal

GDP P(t)Y(t)when ε<1. |

As prices decline

in response to technological progress, nominal GDP decreases over time,

illustrating Lemma 2(i).

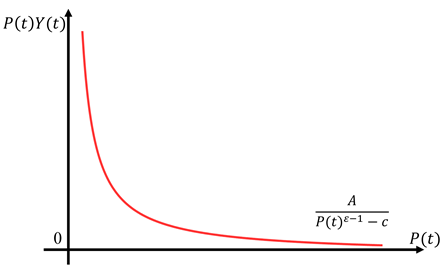

|

Figure 2 (b) Dynamics

of Nominal GDP P(t)Y(t)when ε>1 |

As prices decline

in response to technological progress, nominal GDP increases over time,

illustrating Lemma 2(ii).

Figures 2(i) and 2(ii), in conjunction with Lemma 1, lead to the

following result, stated as Lemma 2.

Lemma 2.

(i)If ε<1, technological progress induces a

monotonic decline in nominal GDP, P(t)Y(t), despite continuous growth in real

output.

(ii)If

ε>1, technological progress induces a monotonic increase in nominal

GDP, P(t)Y(t).

M(t)is given at

the beginning of period t,. Hence, from equation (2),

a decrease in P(t)Y(t)leads to an increase in F(t). Combining this result with

Lemma 1 and Lemma 2(i), we obtain the following

Proposition.

Proposition.

When the price

elasticity of demand is sufficiently low (ε<1), technological progress

generates immiserizing growth in nominal terms:

nominal GDP declines over time, while the trading volume of foreign currency

increases.

Concluding remarks

This paper has

shown that technological progress can generate immiserizing

growth in nominal terms by sharply reducing prices and, consequently, nominal

GDP. Unlike the traditional literature, which focuses on welfare or real

income, our analysis highlights the central role of the GDP deflator in shaping

macroeconomic outcomes.

The results also

suggest a novel interpretation of rising foreign currency transactions in

low-inflation or deflationary environments: foreign asset accumulation may

reflect not only precautionary motives but also a mechanical consequence of

declining nominal income. This perspective may help to reconcile persistent

external surpluses with weak nominal growth observed in several advanced

economies.

Extending the

model to incorporate unemployment, endogenous growth, and two-way foreign asset

trading remains an important avenue for future research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Adler, G., Lisack, N., and Mano, R. (2019). Large-Scale Foreign Exchange Intervention: Evidence from a New Dataset (IMF Working Paper No. 19/40). International Monetary Fund.

Aizenman, J., and Lee, J. (2007). International Reserves: Precautionary Versus Mercantilist Views, Theory and Evidence. Open Economies Review, 18(2), 191-214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-007-9030-z

Bhagwati, J. (1958). Immiserizing Growth: A Geometrical Note. Review of Economic Studies, 25(3), 201-205. https://doi.org/10.2307/2295990

European Central Bank. (2006). The Accumulation of Foreign Reserves (ECB Occasional Paper Series No. 43).

Forbes, K. (2019). Inflation Dynamics: Dead, Dormant, or Determined Abroad? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring, 257-338. https://doi.org/10.1353/eca.2019.0015

Fujita, Y. (2025). Reconsidering the Immiserizing Growth in a Simple Domestic Macroeconomic Model with Financial Assets. Archives of Business Research, 13(3), 237-241. https://doi.org/10.14738/abr.133.18343

Gopinath, G. (2015). The International Price System. In Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium Proceedings. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. https://doi.org/10.3386/w21646

International Monetary Fund. (2011). Reserve Accumulation and International Monetary Stability (IMF Policy Paper).

Kehoe, T. J., and Ruhl, K. J. (2008). Are Shocks to the Terms of Trade Shocks to Productivity? Review of Economic Dynamics, 11(4), 804-819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.red.2008.04.001

Kohli, U. (2004). Real GDP, Real Domestic Income, and Terms-of-Trade Changes. Journal of International Economics, 62(1), 83-106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2003.07.002

Reinsdorf, M. (2010). Terms of Trade Effects: Theory and Measurement. Review of Income and Wealth, 56(S1), S177-S205. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4991.2010.00384.x

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© Granthaalayah 2014-2026. All Rights Reserved.