Original Article

INFLUENCE OF BACTERIOSPERMY ON THE LEVEL OF APOPTOSIS OF EJACULATED SPERMATOZOODS

INTRODUCTION

Since ejaculate is

a mixture of secretions obtained from the urogenital tract and male accessory

glands, seminal fluid culture reveals the presence of microbes in any part of

the seminal tract De Francesco et al. (2011). In recent years, increasing attention has

been paid to urogenital tract infections; many microorganisms may be involved

in the pathogenesis of diseases of the male reproductive system Shash et al.

(2023). Bacterial infiltration of the male

reproductive system triggers a local immune response, which is usually

accompanied by the release of cytokines and leukocytospermia

Frączek and Kurpisz (2015),Agarwal et al. (2018),Ventimiglia et al.(2020), which is often associated with a decrease

in male reproductive capacity. Finally, there is an opinion that bacterial

metabolism can alter the biochemical or physicochemical characteristics of

seminal plasma or the medium used for sperm processing, which may compromise

sperm survival both in vivo and in vitro Heidari Pebdeni et al. (2022). There is growing evidence that certain

bacterial species contribute to deterioration of sperm quality by directly

reducing sperm viability and motility, altering sperm morphology, and

indirectly affecting sperm quality through oxidative stress and immune or

autoimmune reactions Domes et

al. (2012). However, the most important mechanism

leading to the death of ejaculated sperm during urogenital tract

inflammation/infection is related to apoptosis.

Microorganisms

have been detected in semen Frączek and Kurpisz (2015) with varying effects on the reproductive

tract and sperm quality. However, no extensive studies have been conducted

linking the type of bacteriospermia and the level of

apoptosis in ejaculated sperm.

The aim of the

work: to conduct a comparative study of the influence of different types of bacteriospermia on the apoptosis of ejaculated human

spermatozoa.: to conduct a comparative study of the influence of different

types of bacteriospermia on the apoptosis of

ejaculated human spermatozoa.

Material and Methods

The study group

consisted of 20 healthy, fertile, normozoospermic

volunteers aged 20 to 35 years, recruited from the Astrakhan Center for Family Health and Reproduction, and 62 patients

with various types of bacteriospermia, treated at

urology hospitals in Astrakhan and Akhtubinsk. All

patients provided written consent to participate in the study. Semen samples

were obtained by masturbation after 3–5 days of sexual abstinence. After

liquefaction (30 minutes at room temperature), the samples were subjected to

routine semen analysis in accordance with recommendations published by the

World Health Organization Lutsky

et al. (2023). All samples were subjected to

microbiological analysis. Semen samples were plated on blood agar (BA) and

MacConkey agar (MCA) plates in the microbiology laboratory within 3 hours of

sample collection, according to WHO recommendations, followed by aerobic

incubation at 37°C for 24–48 hours. Samples with significant bacterial growth

(≥ 106 CFU/ml) were further tested to the species level using biochemical

identification tests. For Gram-positive bacteria: Gram stain, catalase, slide

coagulase, novobiocin, bacitracin, bile esculin, and optochin; for

Gram-negative bacteria: Gram stain, TSI agar (triple sugar iron), SIM test

(motility, indole, sulfur), Simmons citrate, urease,

and oxidase Koneman

et al. (1997). Semen samples with normal semen parameters,

no antisperm antibodies, and no signs of bacterial

infection (peroxidase-positive leukocytes <0.2 × 10 /ml and negative

bacterial culture) were selected as controls. Sperm from the collected semen

samples were separated from seminal plasma by centrifugation at 600 g for 8

min. The semen pellets were washed with warm phosphate-buffered saline (PBS),

pH 7.4, and adjusted to a final concentration of 4 × 10 sperm/ml PBS. Apoptosis

was analyzed by flow cytometry. The ANNEXIN V-FITC

APOPTOSIS DETECTION KIT I (BD Pharmingem™, USA) was

used to further confirm apoptosis. Sperm suspensions (2 × 10 6 /mL) were washed

once with PBS supplemented with Ca 2+ and then double-stained with annexin

V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI). After 15 min of incubation on ice in the

dark, the cells were diluted 1 × 1 with binding buffer consisting of 10 mM

HEPES, 140 mM NaCl, and 3.3 mM CaCl2. The apoptotic status in each group was

determined by flow cytometry on an Attune® NxT flow

cytometer according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the data were analyzed using FlowJo software.

Results and discussion

Among 82 semen

cultures (including controls), 47.56% had positive bacteriospermia,

of which Gram-negative bacteria were isolated with a significant predominance

(72.05% of all positive cultures). E. coli (14.63% of total cultures) was the

most frequently isolated bacterium, followed by K. pneumoniae (10.98%) and

Acinetobacter s (7.31%). Staphylococcus haemolyticus

(6.1%), Bacteroides ureolyticus (4.88%), and

Lactobacillus s (3.66%).

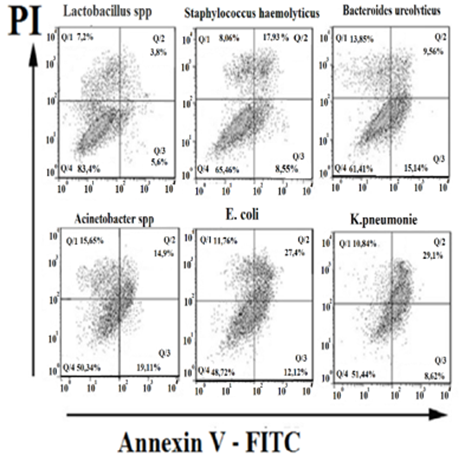

To quantify bacteriospermia-induced apoptosis in ejaculated

spermatozoa, flow cytometry analysis was performed after double labeling with Annexin V-FITC/PI. Sperm were isolated from

ejaculates with positive cultures for apoptosis assessment Table 1. Sperm from ejaculates with normal spermogram parameters and negative bacteriological results

were used as controls. Using multiparameter analysis and simultaneous cell

staining with nucleic acid dyes that do not penetrate living cells, such as

propidium iodide (PI), allows differentiation between cells in the early phase

of apoptosis (AnV+PI-), late apoptosis (AnV+PI+), and dead cells (AnV-PI+).

The ability to simultaneously assess membrane marker expression and AnV staining is highly valuable, allowing characterization

of the apoptotic cell population.

The cell profile

dot plots shown were obtained in 1 of 5 independent experiments that yielded

similar results. Quadrant Q1 reflects necrotic cells (AnV-PI+),

quadrant Q2 reflects late apoptosis (AnV+PI+),

quadrant Q3 reflects early apoptosis (AnV+PI-), and

quadrant Q4 reflects the percentage of viable cells (AnV-PI-).

As shown in Fig. 1, the proportion of apoptotic ejaculated spermatozoa

significantly increased overall in bacteriospermia. Table 1 was compiled based on the dot graphs, which

clearly reflects the dynamics of changes in the level of apoptotic spermatozoa.

Figure 1

|

Picture 1 Flow

Cytofluorimetry of Apoptosis Induction in Ejaculated Sperm Depending on the

Type and Type of Microorganisms During Bacteriospermia.

Scatter Plots After Double Labeling with Annexin

V‑FITC and PI. The X-Axis Represents FITC Staining and the Y-Axis

Represents PI (Propidium Iodide) Staining. |

Externalization of

phosphatidylserine or early apoptosis in the case of Lactobacillus spp does not differ significantly from the control group,

but overall, the total apoptosis caused by Lactobacillus spp

is twice as high as the control Table 2. It has been suggested that lactobacilli

induce apoptosis due to the production of hydrogen peroxide, which causes

non-selective apoptosis Krüger

and Bauer (2017). A comparison of the early and late

apoptosis rates for various pathogens causing bacteriospermia

is also noteworthy. While Staphylococcus haemolyticus

and K. pneumoniae induce minor early apoptosis, late apoptosis under the

influence of these bacteria is much more pronounced Table 2. In the case of staphylococcal infection,

the main proapoptotic factors are numerous toxins characteristic of

staphylococci, including Staphylococcus haemolyticus.

Some toxins cause membrane damage and externalization of phosphatidylserine,

others activate caspases and DNA degradation, which is manifested in a positive

reaction to annexin and a positive reaction to propidium iodide (Ann+PI+), called late apoptosis Zhang et

al. (2017). K. pneumoniae exhibits high adhesive

capacity to the surfaces of various cells, thanks to P-glycoprotein and causes Ann+PI+ apoptosis, and also promotes transcriptional

expression of pro-inflammatory genes IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, as well as the

production of IL-8, IL-1β and TNF-α, which in turn are also

pro-apoptotic factors Cheng et

al. (2020).

Table 1

|

Table 1 Bacteriospermia.

Types and Types of Pathogens |

||||

|

pathogen |

Type |

Number

of positive cultures |

% From

the total number of crops |

% From

the number of positive cultures |

|

E. coli |

gram

negative |

12 |

14,63% |

30,77% |

|

K.

pneumoniae |

gram

negative |

9 |

10,98% |

23,08% |

|

Acinetobacter s |

gram

negative |

6 |

7,31% |

15,38% |

|

Staphylococcus

haemolyticus |

gram-positive |

5 |

6,1% |

12,82% |

|

Bacteroides

ureolyticus |

gram

negative |

4 |

4,88% |

10,26% |

|

Lactobacillus

s |

gram-positive |

3 |

3,66% |

7,69% |

Table 2

|

Table 2 Changes in the Level of Apoptosis of

Ejaculated Spermatozoa Depending on the Type and Kind of Microorganisms in Bacteriospermia (in the Table, all Reliabilities are

Calculated in Relation to the Control) |

||||||

|

type

of bacteria |

Аnn+PI- Early

apoptosis |

р |

Аnn+PI+ Late

apoptosis |

р |

Total Apoptosis |

р |

|

control |

3,8±0.72 |

- |

1,9±0,21 |

- |

4,7±0,61 |

- |

|

Lactobacillus

s |

5,6±0,38 |

0.0627 |

3,8±0,31 |

0.0267 |

9,4±0,35 |

0.00023 |

|

Staphylococcus

haemolyticus |

8,55±0,35 |

0.0008 |

17,93±0,35 |

0.000027 |

26,48±0,62 |

0.000001 |

|

Bacteroides

ureolyticus |

15.14±0,32 |

0.00002 |

9,56±2,75 |

0.0274 |

24,74±1,07 |

0.000001 |

|

Acinetobacter spp |

19,11±0,86 |

0.00003 |

14,9±1,9 |

0.000253 |

34,01±3,7 |

0.000106 |

|

E. coli |

12,12±0,84 |

0.0003 |

27,4±1,8 |

0.000002 |

39,52±2,56 |

0.000001 |

|

K.

pneumoniae |

8,62±0,8 |

0.00288 |

29,1±2,85 |

0.00003 |

37,72±3,83 |

0.000061 |

Gram-negative

bacteria (e.g., Escherichia coli) contain negatively charged molecules such as

phosphatidylglycerol and phosphates in their cell membranes Matsumoto (2001), whereas healthy mammalian cells mainly

contain phospholipids with a neutral charge, and bacterial lipids provoke the

externalization of phosphatidylserine, initiating the signaling

phase of apoptosis Boon and Smith (2002). Escherichia coli, a facultative anaerobe,

is a major cause of urinary tract infections Beebout

et al. (2022), and according to our data, bacteriospermia caused by Escherichia coli has the greatest

pro-apoptotic effect on ejaculated spermatozoa. Studies have shown that in

mouse cells infected with Escherichia coli (E. coli), there was an increase in

the content of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, leptin and resistin, and an increase in the levels of apoptotic

proteins (caspase-3, caspase-9 and bax/bcl-2) Guo et al. (2021).

Flow cytometry

also allows us to assess the percentage of necrotic AnV-PI+

cells, which is particularly important for assessing the viability of

ejaculated sperm. According to our data, the percentage of necrotic cells among

sperm isolated from semen containing Gram-positive bacteria averaged 7.9±0.62%,

while the percentage of necrotic cells in sperm isolated from semen containing

Gram-negative bacteria averaged 13.025±0.84%, which is 64% higher than in

Gram-positive bacteriospermia.

Conclusion

Thus, it is shown that semen contains unique

microbial profiles that appear to be characteristic of a certain subpopulation

of men. E. coli was the most frequently isolated bacterium, followed by K.

pneumoniae, Staphylococcus haemolyticus, Bacteroides ureolyticus, Lactobacillus s These observations are

consistent with previous studies Farahani

et al. (2021). Many of the bacterial species identified in

this study have a significant impact on the development of sperm apoptosis.

These are primarily gram-negative bacteria E. coli and K. pneumoniae. Many

types of bacteriospermia are characterized by a

decrease in the functional characteristics of sperm and, as a result,

subfertility and infertility Heidari Pebdeni et al. (2022). It can be speculated that microorganisms

can influence the environment in which sperm mature, thereby influencing their

physiology, in other words, inducing sperm apoptosis. Apoptosis induced by the

sperm microbiota may be one of the mechanisms underlying male infertility. The

development of new biomarkers for male infertility is crucial for improving the

diagnosis and prognosis of this disease

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Agarwal, A., Rana, M., Qiu, E., AlBunni, H., Bui, A. D., and Henkel, R. (2018). Role of Oxidative Stress, Infection and Inflammation in Male Infertility. Andrologia, 50(11), e13126. https://doi.org/10.1111/and.13126

Beebout, C. J., Robertson, G. L., Reinfeld, B. I., Blee, A. M., Morales, G. H., Brannon, J. R., and Chazin, W. J. (2022). Uropathogenic Escherichia Coli subverts Mitochondrial Metabolism to Enable Intracellular Bacterial Pathogenesis in Urinary Tract Infection. Nature Microbiology, 7(9), 1348–1360. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-022-01205-w

Boon, J. M., and Smith, B. D. (2002). Chemical Control of Phospholipid Distribution Across Bilayer Membranes. Medical Research Reviews, 22(3), 251–281. Https://Doi.Org/10.1002/Med.10009

Cheng, J., Zhang, J., Han, B., Barkema, H. W., Cobo, E. R., Kastelic, J. P., and Zhou, M. (2020). Klebsiella Pneumoniae Isolated from Bovine Mastitis is Cytopathogenic for Bovine Mammary Epithelial Cells. Journal of Dairy Science, 103(4), 3493–3504. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2019-17458

De Francesco, M. A., Negrini, R., Ravizzola, G., Galli, P., and Manca, N. (2011). Bacterial Species Present in the Lower Male Genital Tract: A Five-Year Retrospective Study. European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care, 16(1), 47–53. https://doi.org/10.3109/13625187.2010.533219

Domes, T., Lo, K. C., Grober, E. D., Mullen, J. B., Mazzulli, T., and Jarvi, K. (2012). The Incidence and Effect of Bacteriospermia and Elevated Seminal Leukocytes on Semen Parameters. Fertility and Sterility, 97(5), 1050–1055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.01.124

Farahani, L., Tharakan, T., Yap, T., Ramsay, J. W., Jayasena, C. N., and Minhas, S. (2021). The Semen Microbiome and its Impact on Sperm Function and Male Fertility: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Andrology, 9(1), 115–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/andr.12886

Frączek, M., and Kurpisz, M. (2015). Mechanisms of the Harmful Effects of Bacterial Semen Infection on Ejaculated Human Spermatozoa: Potential Inflammatory Markers in Semen. Folia Histochemica et Cytobiologica, 53(3), 201–217. https://doi.org/10.5603/FHC.A2015.0019

Frączek, M., Hryhorowicz, M., and Gill, K. (2016). The Effect of Bacteriospermia and Leukocytospermia on Conventional and Nonconventional Semen Parameters in Healthy Young Normozoospermic Males. Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 118, 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jri.2016.08.006

Guo, H., Zuo, Z., Wang, F., Gao, C., Chen, K., Fang, J., Cui, H., Ouyang, P., Geng, Y., Chen, Z., Huang, C., Zhu, Y., and Deng, H. (2021). Attenuated Cardiac Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Apoptosis in Obese Mice with Nonfatal Infection of Escherichia Coli. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 225, 112760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112760

Heidari Pebdeni, P., Saffari, F., Mirshekari, T. R., Ashourzadeh, S., Taheri Soodejani, M., and Ahmadrajabi, R. (2022). Bacteriospermia and its Association with Seminal Fluid Parameters and Infertility in Infertile Men, Kerman, Iran: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Reproductive BioMedicine, 20(3), 202–212. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijrm.v20i3.10712

Koneman, E. W., Allen, S. D., Janda, W. M., Schreckenberger, P. C., and Winn, W. C. (1997). Diagnostic Microbiology: The Nonfermentative Gram-Negative Bacilli ( 253–320). Lippincott-Raven.

Krüger, H., and Bauer, G. (2017). Lactobacilli Enhance Reactive Oxygen Species-Dependent Apoptosis-Inducing Signaling. Redox Biology, 11, 715–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2017.01.015

Lutsky, D. L., Nikolaev, A. A., and Lutskaya, A. M. (2023). Guide to the Study of Human Ejaculate (2nd rev. ed.). Astrakhan.

Matsumoto, K. (2001). Dispensable Nature of Phosphatidylglycerol in Escherichia coli: Dual Roles of Anionic Phospholipids. Molecular Microbiology, 39(6), 1427–1433. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02320.x

Shash, R. Y. M., Mohamed, G. A. A., Shebl, S. E., Shokr, M., and Soliman, S. A. (2023). The Impact of Bacteriospermia on Semen Parameters Among Infertile Egyptian Men: A Case–Control Study. American Journal of Men’s Health, 17(3), 15579883231181861. https://doi.org/10.1177/15579883231181861

Ventimiglia, E., Capogrosso, P., Boeri, L., Cazzaniga, W., Matloob, R., Pozzi, E., Chierigo, F., and Abbate, C. (2020). Leukocytospermia is Not an Informative Predictor of Positive Semen Culture in Infertile Men: Results from a Validation Study of Available Guidelines. Human Reproduction Open, 2020(3), hoaa039. https://doi.org/10.1093/hropen/hoaa039

Zhang, X., Hu, X., and Rao, X. (2017). Apoptosis Induced by Staphylococcus Aureus toxins. Microbiological Research, 205, 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2017.08.006

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© Granthaalayah 2014-2026. All Rights Reserved.