Original Article

Political Elites Rebellion and Its Impact on South Sudan

INTRODUCTION

Background of the study

Personal,

political, military, social, or religious grievances can lead to a rebellion,

which is a mass movement for destruction of a country. Rebellions and civil

wars are not solely motivated by opportunistic greed or by long-standing

grievances as argued by Collier

and Hoeffler (2004) rather, academics contend that people rebel

because they feel as though they are being denied the financial advantages or

social standing that they are entitled to. Potential rebels might also be

discouraged from rebelling if they would have to give up important economic

possibilities and obligations. Collectively, these problems demonstrate that

equitable government and economic opportunity should lessen the incentives and

chances for rebellion. One of the first reasons for why humans fight is that they

have innate enmity for other groups. According to this explanation, grievances

and feuds build up over centuries until members of different racial, ethnic, or

religious groups despise one another, frequently having forgotten or

misinterpreted the original and long-ago triggers. They then get ready to fight

and murder each other at any moment.

Ancient hatreds

were prominently mentioned in accounts of the atrocities in Bosnia and Rwanda.

Bosnia allegedly plunged into civil war in 1992 as a result of the collapse of

communism, which released primal hatreds among Serbs, Croats, and Bosniak

neighbours. Some traced these animosities back to the fourth-century divide

between Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Christianity that spanned the Balkans.

Similarly, the Rwandan genocide is frequently described as a reflection of

Hutus' fundamental hatred for Tutsis. Citing ancestral hatreds offers a simple

reason for ethnic violence. However, it is nearly certainly incorrect. Multiple

studies have revealed little, if any, correlation between a country's ethnic or

religious variety and its risk of experiencing civil war. Furthermore, it

appears that whether distinct groups display even modest enmity, it is heavily

influenced by circumstances. For example, Daniel Posner discovered that the

Chewa and Tumbuka ethnic groups display tremendous enmity in Malawi, yet the

same groups are fairly cordial in Zambia, even agreeing to marry across ethnic

lines. Similarly, prior to the civil conflict in Bosnia, one-quarter of

marriages crossed ethnic and religious lines.

A popular example

of how resources can fuel conflicts is diamond, as highlighted in the book

Blood Diamond During Sierra Leone’s Civil War, that rebel groups would captured

easily mined diamond fields. These diamonds were then smuggled out of the

country, helping to finance a rebellion or civil war. The rebels argued that

certain natural resources, such as oil, are associated with an increased

likelihood of conflict or insurgency, and other resources, such as diamonds,

are associated with increased insurgency or conflict duration. This is because

natural resources can lower the cost of starting a war and provide rebels with

an easy way to finance protracted conflicts. Natural resources can also make it

more profitable for the state to claim the prize, further reducing the

opportunity costs of rebellion. For the same reason, Collier and Hoeffler also

conclude that states with low GDP per capita are more likely to experience

civil war and insurgency because low median incomes make conflict a more

profitable option Collier

and Hoeffler (2004).

Fearon,

and Laitin (2003) offer the opposite view. They see

opportunity structures created by state weakness as the cause of rebellion or

civil war. They find evidence in favour of riot technology as a mechanism. In

addition, they find that ethnicity, religion, or any cultural or demographic

characteristics do not seem to be positively associated with the beginning of

civil war. Economic factors are likely to play a role in the conflict, likely

to generate grievances Fearon,

and Laitin (2003). In Why Men Rebel, Ted Gur argues that

people are motivated to rebel by “relative deprivation” rather than absolute

poverty or pure greed. Basically, “relative disadvantage” is a group’s feeling

and belief that they have not received the economic benefits or political voice

they believe they are entitled to. This sense of injustice causes conflict. In

addition, groups are often particularly motivated by the fact that they have

lost advantages or power they once enjoyed, or fear that a change in circumstances

will lead to a loss of power and economic advantages Ted

(1970).

Since gaining

independence in 2011, South Sudan has experienced chronic political instability

and civil conflict. Central to these conflicts are the actions and rebellions

of political elites, whose motivations and impacts are complex and

multifaceted. Despite their significant role in the ongoing turmoil, the

specific reasons why these elites choose to rebel and the impacts of their

actions are not well understood. This gap in understanding hinders effective

conflict resolution and governance strategies.

The purpose of this study

The study seeks to

move beyond surface-level grievances and analyse the strategic calculations,

motivations, and limitations that drive South Sudanese elites to rebel. This

involves examining the interplay of personal ambition, ethnic loyalties, access

to resources, and the pursuit of power within the context of a fragile state.

Ultimately, this study seeks to provide a nuanced and comprehensive

understanding of the complex dynamics surrounding elite-led rebellions in South

Sudan, moving beyond simplistic narratives to reveal the often-invisible ways

in which these conflicts shape the country’s political landscape.

Statement of problem

Despite the

frequent occurrence of elite rebellions in South Sudan, particularly in Juba,

their impacts often remain invisible to both the local and international

communities. This phenomenon presents a significant challenge to understanding

and addressing the root causes of instability in the country Johnson

(2014). The political elites in South Sudan are

deeply divided along ethnic lines, primarily between the Dinka and Nuer tribes.

These divisions foster a climate of mistrust and conflict, yet the consequences

of elite actions are often overshadowed by the broader ethnic tensions.

Persistent power struggles between key political figures, such as President

Salva Kiir and his former deputy Riek Machar, have led to recurrent cycles of

violence and rebellion. However, the visible impact of these power struggles on

governance and public life is often obscured by ongoing conflicts and

humanitarian crises Jok (2011).

Control over

lucrative resources, especially hydrocarbons, is a major driver of elite

rebellion. Corruption and patronage networks complicate the political

landscape, but the tangible effects on economic development and public welfare

remain difficult to discern due to widespread poverty and infrastructure

challenges Patey

(2014). The continuous conflict has resulted in a

severe humanitarian crisis, with millions of people displaced. The focus on

immediate humanitarian needs often overshadows the political dynamics and their

specific impacts, making it hard to attribute changes to particular elite

actions. South Sudan's fragile state institutions struggle to implement and

sustain reforms. The frequent changes in leadership and policy rarely lead to

significant, visible impacts on the ground due to the lack of effective

governance structures De Waal (2014).

While significant

research has been conducted by Dr. Luka Patey in (2014) on the causes and

consequences of political instability in South Sudan, there remain several

critical gaps in understanding the specific impacts of elite rebellions and why

these impacts often remain invisible. These gaps hinder effective policy-making

and intervention strategies aimed at fostering stability and development in the

country. Addressing these research gaps is crucial for developing a more

comprehensive understanding of the political dynamics in South Sudan and

improving the effectiveness of interventions aimed at stabilizing the country.

By focusing on micro-level impacts, the intersection of humanitarian and

political issues, institutional responses, media practices, and comparative

analysis, this study can provide deeper insights into the reasons why the

impacts of political elite rebellions in South Sudan remain invisible Copnall

(2014).

Research Objectives

Broad objective

To examine the

phenomenon of political elites’ rebellion in South Sudan and its impacts on the

country’s political stability and development.

Specific objectives

1)

To

identify the primary motivations behind the rebellions of political elites in

South Sudan.

2)

To

investigate the effects of rebellions on the people of South Sudan.

3)

To

explore the potential paths towards conflict resolution and peacebuilding in

the context of political elites’ rebellion in South Sudan.

Research Questions

1)

What are

the primary motivations behind the rebellions of political elites in South

Sudan?

2)

What are

the effects of rebellions on the people of South Sudan?

3)

What

will be the way forward towards conflict resolution and peacebuilding in the

context of political elites’ rebellion in South Sudan?

Significance of the Problem

Addressing these

problems is critical for several reasons:

·

A deeper

understanding of elite motivations and the hidden impacts of their actions can

inform more effective policy and peacebuilding interventions that target the

root causes of conflict.

·

Conflict

resolution: by highlighting the less visible consequences of elite actions,

this study can contribute to more holistic conflict resolution strategies that

go beyond immediate humanitarian responses.

·

Academic

contribution: this study will add to the academic discourse on political

instability and conflict, providing insights that can be applied to other

post-colonial states facing similar challenges.

Justification

The persistent

conflict and political instability in South Sudan pose significant challenges

to peacebuilding, governance, and development. Understanding the underlying

factors driving these issues is essential for crafting effective interventions.

This study focuses on the motivations behind political elite rebellions and the

often-invisible impacts of their actions, which are crucial yet underexplored

dimensions of the conflict in South Sudan. Informed policy making is imperative

by identifying the motivations behind elite rebellions, policymakers can

develop targeted strategies to address the root causes of conflict. This can

lead to more effective peacebuilding efforts and the stabilization of political

institutions. Besides, improved governance is critical through understanding

the invisible impacts of elite actions in creating governance structures that

are more resilient to manipulation and subversion by political elites. This can

strengthen state institutions and promote long-term stability.

In addition,

theoretical advancement is essential by applying and testing theories of

political instability, elite behavior, and conflict in the context of South

Sudan. The study can refine and expand existing theoretical frameworks.

Practical implication is desirable through detailed insights into elites’

motivations and the indirect consequences of elites’ actions can inform the

design of comprehensive conflict resolution mechanisms that address both

visible and hidden dimensions of the conflict. Understanding the less visible

impacts of elite rebellions can improve the effectiveness of humanitarian

interventions by highlighting areas that may be neglected due to a lack of

visibility in media and policy discussions.

Limitation of the study

The delimitation

of the study is that, it relied on secondary data that is more accessible to

primary data whose acquisition is limited. The primary data was collected from

the accessible population, whereas the general and target population

information was acquired through secondary data. The study focused on political

elites’ rebellion and its impact on South Sudan. The study's limitations

include the constrained time, resources, and access to government data.

Conceptual framework

|

|

|

Source:

Researchers, 2025 |

The conceptual

framework above consists of independent variables and dependent variable.

Independent variables consist of political motivation, economic motivation and

personal motivations. Dependent variable is the effect and consists of

rebellion which is caused by independent variables that led to elite

fragmentations and conflicts in South Sudan.

Literature Review

Main motives behind the rebellions of political elites in South Sudan.

Ethnic tensions and identity politics

Ethnicity has

historically been a critical factor in the political landscape of South Sudan.

Political elites often mobilize their ethnic constituencies as a means to

solidify their political influence. In a highly diverse country, this

politicization of ethnicity has led to factionalism within the state, with

elites frequently competing for power through ethnic lines rather than national

cohesion. The rivalry between President Salva Kiir (Dinka) and former Vice

President Riek Machar (Nuer) is a prime example of how ethnic politics drive

rebellion and conflict. The 2013 civil war, triggered by political

disagreements, quickly escalated into an ethnic conflict, largely due to the

way political leaders harnessed ethnic grievances for their own advantage. Ethnic

tensions and identity politics have played a critical role in shaping the

political landscape of South Sudan, both before and after the country’s

independence in 2011. The politicization of ethnicity is deeply rooted in the

country’s colonial history and has been exacerbated by successive conflicts,

ultimately becoming a powerful force behind political elite rebellions. The

manipulation of ethnic identities by political leaders for personal and

political gain has contributed to the destabilization of South Sudan, fueling

cycles of violence and rebellion. This expanded section will delve deeper into

the historical context, the ethnic divide, the role of elites, and the

consequences of ethnic politics on rebellion Rolandsen

(2015).

Historical context: colonial legacy and ethnic fragmentation

The ethnic

divisions in South Sudan can be traced back to the colonial period when the

British authorities adopted policies that emphasized and reinforced ethnic

identities. During colonial rule, the British practiced a policy of indirect

rule, where they governed the southern region of Sudan through local chiefs,

often based on ethnic affiliation. This system institutionalized ethnic

divisions by privileging certain ethnic groups over others and laying the

groundwork for ethnic competition over resources and political influence. The

colonial government also geographically and politically isolated the southern

part of Sudan from the northern part, fostering deep mistrust between the two

regions. Southern Sudanese, many of whom were from ethnic groups such as the

Dinka, Nuer, Shilluk, and Azande, felt marginalized by the northern government,

which was dominated by Arab and Muslim elites. This historical marginalization

fueled grievances that later found expression in two civil wars (1955-1972 and

1983-2005) between the northern government and southern rebels, including the

Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA).

After decades of

civil war, the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) in 2005 and South Sudan’s

subsequent independence in 2011 did not resolve the ethnic tensions but instead

provided a new platform for ethnic competition among southern elites. Ethnicity

remained a central factor in politics as leaders sought to secure power by

mobilizing their ethnic constituencies, which has created new forms of rivalry

and distrust Jok (2015).

The Ethnic Divide: Dinka and Nuer rivalry

The rivalry

between the Dinka and Nuer, the two largest ethnic groups in South Sudan, has

been one of the most prominent examples of how ethnic divisions drive political

conflict. The Dinka, the largest ethnic group, has historically dominated the

country’s political landscape, particularly since independence. President Salva

Kiir, a Dinka from the Bahr el Ghazal region, has used his ethnic base to

consolidate power within the government and the military. This has led to

accusations of favoritism and marginalization from other ethnic groups,

particularly the Nuer. The Nuer, the second-largest ethnic group, has been at

the forefront of political opposition to the Dinka-dominated government. Riek

Machar, a Nuer leader and former Vice President, has positioned himself as a

representative of Nuer grievances against the Dinka-led government. The rivalry

between Machar and Kiir came to a head in December 2013, when a political

dispute within the ruling Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) escalated

into a full-scale civil war. What began as a political struggle quickly took on

ethnic overtones, with the Dinka and Nuer mobilizing along ethnic lines Young (2016). The conflict led to horrific

violence, with both sides targeting civilians based on their ethnicity. Human

rights organizations documented mass killings, rapes, and other atrocities

committed against both Dinka and Nuer civilians during the war. The ethnicization

of the conflict deepened the divide between the two groups, making

reconciliation and peacebuilding efforts even more challenging.

Elite manipulation of ethnicity for political gain

Ethnicity has been

a tool for political elites in South Sudan to mobilize support and gain

political influence. Elites have often framed political disputes in ethnic

terms, using the grievances of their ethnic groups to justify their claims to

power. This tactic not only helps them rally support but also deflects

attention from personal ambitions or broader political issues. Salva Kiir’s

consolidation of power within the SPLM, particularly after the death of John

Garang in 2005, has been viewed by other ethnic groups as a way of maintaining

Dinka dominance within the government. Kiir’s decision to dismiss Riek Machar

and other prominent Nuer figures from their positions in 2013 was perceived as

an ethnic power grab, leading to Machar’s rebellion. Machar, in turn, mobilized

Nuer forces by framing his rebellion as a defense of Nuer rights and a response

to Dinka dominance. This dynamic has played out repeatedly in South Sudan’s

history, with political elites using ethnic grievances to justify their

rebellions. However, the use of ethnic identity as a political tool has had

disastrous consequences, as it has deepened ethnic divisions and created a

cycle of violence and retribution between groups. Instead of fostering national

unity, the ethnicization of politics has fragmented the state and undermined

efforts to build a cohesive national identity Young

(2016).

Struggles for power and leadership

Power struggles

among South Sudan's political elites have been central to the numerous

rebellions. The country’s leadership structure heavily concentrates power in

the presidency, leading political elites to view the presidency as the ultimate

prize for political and economic control. The 2013 and 2016 civil wars are

clear illustrations of how personal ambitions and political rivalries among

elites, particularly between Kiir and Machar, have led to violent conflict.

Elites who feel excluded from key positions within the government often resort

to rebellion as a means of renegotiating power structures or gaining leverage

in peace agreements. The struggles for power and leadership in South Sudan have

been a major driving force behind political instability, rebellion, and civil

war. These power struggles are rooted in the country’s complex political

landscape, where leadership positions are highly coveted due to their control

over resources, military power, and government institutions. The absence of

strong democratic institutions, the centralization of power in the executive

branch, and personal rivalries among political elites have all contributed to

intense competition for leadership. This expands from the historical

background, the centralization of power, factionalism within the ruling elite,

and the broader consequences of these leadership struggles De Waal (2014).

South Sudan’s

political landscape is heavily shaped by the legacy of its long struggle for

independence from Sudan. The Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), and its

military wing, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), were the dominant

forces in this liberation struggle, led by figures like John Garang and Salva

Kiir. The SPLM/A’s military success and eventual political victory in securing

South Sudan’s independence in 2011 meant that the movement's leaders became the

de facto rulers of the new state. However, the transition from a liberation

movement to a civic governing body proved difficult. The SPLM/A was built on a

hierarchical, military-style leadership structure, contradictions that lack

democratic mechanisms for resolving disputes or sharing power. As a result,

leadership positions within the SPLM/A, and later within the government of

South Sudan, became highly contentious, with various factions vying for control

Johnson

(2014)

The death of John

Garang in a helicopter crash in 2005, just months after the signing of the

Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) that ended Sudan’s civil war, created a

power vacuum that further intensified the struggle for leadership. Salva Kiir,

Garang’s deputy, assumed leadership of the SPLM and the presidency of the newly

autonomous government of Southern Sudan, but his leadership was immediately

challenged by other senior figures within the movement. These internal power

struggles, which were largely unresolved at the time of independence in 2011,

continued to fester and eventually led to the outbreak of civil war in 2013 and

many other small wars in the nascent state.

Centralization of power in the executive

One of the key

factors driving the struggles for leadership in South Sudan is the extreme

centralization of power in the executive branch, particularly the presidency.

The president appoints and fires at will. He can appoints state officer today

and revoke the appointment tomorrow. Thus, Salva Kiir gives and Salva Kiir

takes, may his name be glorified. Besides, President Kiir wields significant

control over politics, military and country’s resources. This concentration of

power has made the presidency the focal point of political competition among

elites, as controlling the executive office translates into controlling the

state apparatus and resources. Under President Salva Kiir, the executive branch

has increasingly consolidated power, sidelining other political institutions,

such as the legislature and the judiciary, which remain weak and

underdeveloped. Kiir’s dominance over the military, especially his close ties

with top commanders in the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), has allowed

him to maintain a firm grip on power. However, this centralization has also

created resentment among other political elites, who feel excluded from

decision-making and denied access to state resources Rolandsen

(2015). The concentration of power in the

presidency also means that losing political office can result in a total loss

of influence, which incentivizes elites to resist leadership transitions. As a

result, South Sudan’s political landscape has been marked by attempts to hold

onto power at all costs, often through violent means. Political elites who are

removed from office or feel threatened by the incumbent government frequently

resort to rebellion as a way to renegotiate their access to power.

Factionalism within the ruling elite

Factionalism

within the ruling elite has been a persistent problem in South Sudan’s

political system. Since independence, the SPLM has been plagued by internal

divisions and leadership disputes, particularly between President Salva Kiir

and his former deputy, Riek Machar. These divisions have often revolved around

personal rivalries, but they have also been exacerbated by ethnic affiliations,

with Kiir representing the Dinka ethnic group and Machar representing the Nuer.

The rivalry between Kiir and Machar reached its peak in December 2013, when a

political dispute within the SPLM escalated into a violent conflict. Kiir

accused Machar of attempting a coup, leading to Machar’s dismissal as Vice

President and the subsequent outbreak of civil war. Machar denied the coup

allegations and mobilized forces loyal to him, primarily from the Nuer ethnic

group, sparking widespread violence across the country. This conflict was not

just about ethnic divisions but also about competing visions for the country’s

leadership. Machar had long criticized Kiir’s increasingly autocratic

leadership style and sought to position himself as a reformer within the SPLM.

However, his challenge to Kiir’s leadership was seen as a direct threat to

Kiir’s hold on power, leading to a violent confrontation between the two

factions. The rivalry between Kiir and Machar is indicative of a broader

pattern in South Sudan’s political elite, where leadership disputes are often

settled through violence rather than negotiation or democratic means. The absence

of strong institutions to mediate these disputes has meant that political

competition frequently leads to armed conflict, further destabilizing the

country Jok (2015)

Personal rivalries and opportunism

While ethnic and

political divisions are important factors in the power struggles in South

Sudan, personal rivalries and opportunism have also played a key role. Many of

the political conflicts in South Sudan have been driven by the ambitions of

individual leaders who seek to gain or maintain power for personal benefit.

Political office in South Sudan offers access to wealth, patronage networks,

and control over the country’s hydrocarbon resources, which makes leadership

positions highly lucrative. For many political elites, rebellion has become a

tool for bargaining. Leaders who challenge the government through rebellion are

often offered positions of power in exchange for laying down arms. This pattern

of rebellion, negotiation, and co-optation has created a cycle of violence,

where political elites use armed conflict as a way to secure their place within

the government. Riek Machar’s repeated rebellions against the government,

followed by peace agreements that offered him a return to power, are a clear

examples of this dynamic. After the signing of the 2015 peace agreement, Machar

was reinstated as Vice President, only for the peace deal to collapse in 2016,

leading to another round of fighting until 2018 peace deal that built shaky and

risky coalition. This cyclical pattern highlights the role of opportunism in

South Sudan’s leadership struggles, where elites use violence as a strategy to

advance their personal ambitions Arnold (2013).

Consequences of power struggles on governance and stability

The struggles for

power and leadership in South Sudan have had devastating consequences for

governance and stability. The constant infighting among political elites has

weakened state institutions, making it difficult for the government to provide

basic services or maintain law and order. As leaders focus on securing their

positions within the government, they often neglect the needs of the broader

population, contributing to widespread poverty, food insecurity, and

displacement. The violent nature of this leadership struggles has also

undermined peacebuilding efforts. Peace agreements, such as the 2015 Agreement

on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (ARCSS),

failed because it didn’t address the root causes of elite competition. Instead,

it offered temporary power-sharing arrangements that were quickly broken when

one faction feels excluded or threatened. As a result, the country has

experienced repeated cycles of violence and instability, with little progress

toward sustainable governance. Patey (2017).

This is the same with 2018 Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the

Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS) which is at the brink of

collapse due to deep-seated mistrusts amongst the signatories to the Agreement.

The concentration of power in the executive has also stifled the development of

democratic institutions. South Sudan’s political system remains highly

centralized, with little room for opposition or independent views.

Resource control and economic marginalization

South Sudan's

wealth in natural resources, particularly, hydrocarbon has been a significant

motivator for political elites to rebel. Elites often view rebellion as a

pathway to control resource-rich areas, which in turn grants them access to

wealth and economic influence. Many of the key oilfields in South Sudan are

located in areas where elites have historical claims, creating incentives to

challenge central authority for local control of these regions Le Billion (2001). Resource control and economic

marginalization are at the heart of South Sudan’s conflicts and power

struggles. While the country is endowed with significant natural resources,

particularly, oil, which constitutes the backbone of its economy, these

resources have become a curse, as competition over their control has driven

conflict and exacerbated economic inequalities. Economic marginalization,

especially of communities living near resource-rich areas, has further deepened

grievances, fueling political instability and rebellion. This analysis will

explore the role of oil, land control, economic marginalization, corruption,

and the broader consequences of resource struggles in South Sudan.

Indeed, South

Sudan possesses vast oil reserves, which account for more than 80% of its

government. Oil exports are essential for funding public services,

infrastructure projects, and the military. The importance of oil to the

national economy has made control over oil resources a central issue in South

Sudan's political landscape. During the period leading up to South Sudan’s

independence in 2011, oil played a significant role in negotiations with Sudan.

Oil reserves are located primarily in South Sudan, while the infrastructure for

exporting oil (including pipelines and refineries) is located in Sudan. This

geographic split meant that oil became a key bargaining chip in peace

negotiations between the North and the South. Post-independence, disputes over oil

revenues between the two countries further contributed to tensions, leading to

the temporary shutdown of oil production in 2012 Le

Riche and Arnold (2013). Within South Sudan, oil control has fueled

political rivalries and violence. The central government, dominated by the

Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), has sought to maintain tight control

over oil revenues, which has sparked resentment from other political elites and

regions that feel excluded from the benefits. During the civil wars of 2013 and

2016, many of the major battlefronts were located near oil-producing regions,

as rebel forces sought to gain control over these vital resources.

Effect of rebellions on the people of South Sudan

The rebellions in

South Sudan have resulted in profound and multifaceted consequences for the

country, deeply affecting its social structures, economic conditions, and

overall quality of life. Since gaining independence in 2011, South Sudan has

grappled with numerous internal conflicts driven by political power struggles,

ethnic tensions, and disputes over vital resources. These rebellions have

triggered a cycle of violence and instability that has significantly disrupted

the lives of millions. The effect of rebellions on the people of South Sudan is

discussed on the following areas:

Humanitarian crisis

The humanitarian

crisis in South Sudan has reached alarming proportions due to the ongoing

conflicts, significantly worsening food insecurity and health challenges. The

prolonged violence has disrupted agricultural production, leading to chronic

shortages of food. As a result, malnutrition rates have soared, particularly

among vulnerable populations such as children and pregnant women. According to

the United Nations, millions have been displaced from their homes due to

fighting, which has rendered entire communities vulnerable. By late 2023, it

was estimated that over 7.76 million people in South Sudan required

humanitarian assistance, with many facing life-threatening hunger UN OCHA (2023). The World Food Programme (WFP)

reports that over half the population is in dire need of food aid, exacerbating

the crisis as families struggle to meet their basic needs. The effects of this

humanitarian crisis extend beyond immediate food shortages; they also have

significant implications for public health. The conflict has severely strained

the already limited healthcare infrastructure, leaving many without access to

essential services. Diseases such as cholera and malaria have proliferated in

areas lacking sanitation and healthcare resources. With the ongoing violence

making it difficult for humanitarian organizations to operate effectively, the

situation remains precarious. The WFP has noted that the lack of food security

not only leads to immediate health issues but also has long-term consequences

for the population's resilience and ability to recover from the ongoing

conflict WFP (2023). In this context,

addressing food insecurity and improving health services are critical for

stabilizing the humanitarian situation in South Sudan.

Displacement and Migration

The conflicts in

South Sudan have caused massive internal displacements, forcing millions to

flee either to neighboring countries or to United Nations camps. This

displacement disrupts established communities and leads to the disintegration

of social networks and support systems. According to the Internal Displacement

Monitoring Centre (IDMC) Report, there were over 2 million internally displaced

persons (IDPs) in South Sudan as of 2023, significantly impacting their access

to education, healthcare, and economic opportunities IDMC

Report (2023). Displaced individuals often find themselves living in

overcrowded conditions with limited access to basic necessities, making them

more vulnerable to diseases and malnutrition. The loss of livelihoods

exacerbates the plight of IDPs, as many have been forced to abandon their

homes, land, and businesses, plunging them into poverty and increasing their

dependence on humanitarian assistance. Additionally, the influx of IDPs into

urban areas and refugee camps creates pressure on already strained resources

and infrastructure. Host communities often struggle to accommodate the growing

population, leading to competition for limited resources such as food, water,

and healthcare services. This situation can foster tensions between displaced

individuals and host communities, potentially leading to conflict. The United

Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has reported that the influx of

IDPs and refugees can strain local services, further complicating the

humanitarian response and necessitating targeted interventions to address the

needs of both groups United

Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2023). Addressing displacement requires

comprehensive strategies that consider the needs of IDPs while supporting host

communities to mitigate tensions and foster social cohesion.

Violence and insecurity

The rebellions in

South Sudan have resulted in widespread violence, including attacks on

civilians, sexual violence, and targeted killings. These acts of violence

contribute to a climate of fear and insecurity that prevents communities from

rebuilding and often leads to cycles of retribution and further conflict. Human

Rights Watch has documented numerous cases of violence affecting women and

children, who are particularly vulnerable in these situations Human Rights Watch (2023). The prevalence of

violence not only endangers lives but also disrupts social fabric, making it

difficult for communities to re-establish trust and cooperation necessary for

recovery and development. The social repercussions of violence can be

long-lasting, as communities struggle to cope with the trauma and loss that

result from such acts.

Moreover, the

breakdown of law and order exacerbates the security situation, as criminal

gangs and armed groups often exploit the chaos for their gain. The power vacuum

created by weakened state institutions allows these groups to operate with

impunity, undermining efforts to restore stability and governance. Reports

indicate that the lack of effective law enforcement has resulted in increased

incidents of crime and violence, further eroding public confidence in the

government’s ability to protect its citizens Collier

and Hoeffler (2004). This cycle of violence not only impacts

immediate security but also hinders long-term peace-building efforts. The need

for comprehensive security sector reforms and community-based initiatives to

address the root causes of violence is critical for restoring trust and

establishing a safer environment for all citizens.

Economic decline

The ongoing

conflicts have significantly hindered economic development and stability in

South Sudan, creating a challenging environment for growth. Frequent

disruptions to trade, agriculture, and infrastructure have led to weakening of

national currency, South Sudanese Pound (SSP), soaring inflation and increased

poverty rates. The World Bank reported that South Sudan’s GDP has contracted

dramatically since the onset of conflict, resulting in widespread economic

hardship and diminishing opportunities for the populace World

Bank (2023). The instability has deterred foreign

investment, which is crucial for stimulating economic activity and rebuilding

infrastructure. As businesses are destroyed or forced to close, unemployment

rates rise, leaving many families struggling to provide for their basic needs.

Economic decline also exacerbates governance challenges, as the government

faces increasing difficulties in delivering essential services. The lack of

economic activity limits tax revenues, which in turn constrains the

government’s ability to fund education, healthcare, and social programs. This

creates a vicious cycle in which economic decline undermines governance, while

poor governance further hampers economic recovery African

Development Bank Report (2022). As a result, public trust in government

institutions erodes, making it more difficult to implement policies that

promote stability and growth. Addressing the economic decline in South Sudan

requires targeted interventions focused on rebuilding infrastructure, fostering

investment, and creating jobs to restore public confidence and facilitate

recovery.

Social fragmentation and ethnic tensions

Rebellions often

exacerbate ethnic tensions, leading to social fragmentation and deepening

societal divides. Allegiances formed during conflicts can complicate

reconciliation efforts, making unity increasingly challenging. Research by the

African Development Bank highlights how such fragmentation leads to lasting

animosities, perpetuating cycles of violence and instability African Development Bank Report (2022). Ethnic

tensions can arise from competition over resources, political representation,

and historical grievances, often leading to violence and discrimination against

certain groups. This polarization not only weakens community bonds but also

hinders collective efforts to address shared challenges, further entrenching

divisions. Social fragmentation can also have significant implications for

governance and the rule of law. As communities become divided along ethnic

lines, trust and cooperation between different groups diminish, making it

difficult to promote effective governance and uphold the rule of law Collier

and Hoeffler (2004). The lack of social cohesion can lead to

increased crime and violence as individuals prioritize the interests of their

ethnic group over the common good. Additionally, marginalized groups may resort

to informal justice mechanisms, which can lack transparency and accountability,

further undermining the formal legal system Stewart

and Fitzgerald (2001). Addressing social fragmentation and ethnic

tensions requires inclusive policies and initiatives that foster dialogue,

promote reconciliation, and encourage collaboration among diverse groups to

build a more cohesive and peaceful society.

Governance and rule of law breakdown

Rebellions have

significantly weakened the governance structures within South Sudan, leading to

a decline in the rule of law. Many citizens express a lack of trust in

government institutions, attributing this to widespread corruption and

ineffective governance exacerbated by ongoing conflict International

Crisis Group Report (2023). As a result, communities often turn to local

forms of governance, which can vary widely in effectiveness and accountability.

This reliance on informal systems can create disparities in access to justice

and undermine the ability of the government to maintain order and enforce laws,

leading to further instability.

The impact of

conflict on governance is multifaceted and far-reaching. The breakdown of state

institutions responsible for maintaining law and order creates a power vacuum

that allows criminal groups to flourish. Such conditions hinder efforts to

establish a functioning legal system and can result in increased violence and

human rights violations Collier

and Hoeffler (2004). Furthermore, the erosion of trust in

government can lead to social unrest and impede efforts to promote good

governance. Addressing these challenges necessitates comprehensive support for

rebuilding state institutions, enhancing accountability, and restoring public

trust in governance structures Stewart and

Fitzgerald (2001). Early intervention and assistance can play a vital

role in promoting good governance and the rule of law in post-conflict

societies, ultimately paving the way for a more stable and just future.

Long-term psychological effects

The psychological

impact of ongoing conflict in South Sudan cannot be overstated, as many

individuals suffer from trauma related to violence, loss of family members, and

the stress of displacement. Mental health services are scarce in South Sudan,

and the stigma surrounding mental health issues can prevent individuals from

seeking help Médecins Sans Frontières (2023).

The long-term psychological effects of exposure to conflict can manifest in

various ways, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and

anxiety. Children exposed to violence and loss are particularly vulnerable, as

these experiences can hinder their development and educational outcomes Beardslee and Beardslee (2002).

The way forward towards conflict resolution and peacebuilding in the context of political elites' rebellion in South Sudan

Inclusive genuine dialogue

Inclusive genuine

dialogue is essential to address the grievances that drive political elites to

rebel. In South Sudan, fostering dialogue among key stakeholders—including

political elites, rebel groups, civil society organizations, marginalized

communities, and women and youth groups—creates a platform to negotiate

power-sharing agreements and address grievances constructively. Such dialogue

must be comprehensive and inclusive to avoid further fragmentation. According

to Lederach (1997), peacebuilding in deeply

divided societies must involve a broad base of society in dialogues aimed at

reconciliation, including not only political elites but also marginalized

groups who often bear the brunt of violence. This ensures that all groups feel

represented in the peace process, thus reducing the likelihood of continued

rebellion or violence. While South Sudanese national dialogue conducted in 2017

to 2020 was problematic due to un-implementation of its resolutions, conducting

genuine national can help in lessening conflicts and rebellions in South Sudan.

Good governance reforms

Governance reforms

are key to addressing the underlying causes of political conflict and rebellion

in South Sudan. Corruption, weak state institutions, and unequal distribution

of resources fuel grievances among political elites and the general population.

Implementing reforms that promote transformative leadership, transparency,

accountability, and the rule of law can address these grievances and lay the

foundation for sustainable peace. The World Bank

(2020) emphasizes that good governance reforms should prioritize

fighting corruption through the establishment of independent anti-corruption

commissions and ensuring that public institutions are transparent and inclusive

in their service delivery. By enhancing the state’s capacity to deliver public

goods fairly, political elites and marginalized groups may find fewer reasons

to rebel. Additionally, governance reforms that promote decentralization can

empower local governments to provide services more effectively, reducing

regional disparities Rotberg (2014).

Confidence-building measures

Confidence-building

measures (CBMs) are essential in fragile post-conflict environments,

particularly, where mistrust among political elites and rebel groups persists.

Implementing CBMs such as cease-fire agreements, humanitarian access

provisions, and demobilization programs can help de-escalate violence and

restore trust among warring factions. John Paul Lederach (1997) highlights the

importance of incremental steps in peacebuilding through CBMs. These measures

create an environment conducive to dialogue and negotiations by demonstrating

commitment to peace and reducing tensions between conflicting parties. In South

Sudan, such measures could include agreements on demobilization, disarmament,

and reintegration (DDR) of combatants, as well as opening access to

humanitarian aid in conflict zones Höivik and

Galtung (1971).

Reconciliation efforts

Reconciliation is

a critical aspect of peacebuilding, particularly in a country where ethnic

tensions and historical grievances have fueled conflict. Reconciliation efforts

in South Sudan should include Truth and Reconciliation Commissions (TRCs) to

address past atrocities and human rights violations. By providing a platform

for victims and perpetrators to share their experiences, TRCs can contribute to

healing societal divisions and promoting national unity. As noted by Hayner (2011), TRCs have played a crucial role in

post-conflict reconciliation in countries such as South Africa and Sierra Leone

by addressing historical grievances, promoting accountability, and fostering

national healing. In South Sudan, reconciliation efforts should also include

inter-community dialogues that address the ethnic dimensions of the conflict

and promote social cohesion across divided communities Galtung

(1969).

International support

International

support is critical to ensuring the success of peacebuilding initiatives in

South Sudan. Regional organizations such as the African Union (AU), the

Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), and international partners

including the United Nations (UN) and the European Union (EU) can provide

essential technical assistance, financial resources, and mediation efforts.

International actors can help facilitate the implementation of peace

agreements, monitor ceasefires, and provide training for local peacebuilders. Lijphart (1977) argues that international actors

play a crucial role in mediating conflicts in divided societies by ensuring

that peace agreements are enforced and by providing the necessary resources for

rebuilding good governance institutions. International donors can also support

South Sudan by investing in capacity-building initiatives aimed at

strengthening state institutions and ensuring effective governance and service

delivery, thereby addressing the root causes of conflict Lederach (1997).

Power sharing mechanisms

Establishing

power-sharing mechanisms is an effective way of addressing the political

exclusion that fuels rebellion. Lijphart (1977) emphasizes

the need for inclusive governance structures that incorporate different

societal groups, including rebel factions and political elites. This approach

ensures that all stakeholders have meaningful participation in decision-making

processes, reducing the likelihood of rebellion. Lijphart’s theory of

consociational democracy suggests that proportional representation, minority

rights protections, and coalition governments can provide political elites with

the opportunity to engage in non-violent, democratic processes. In South Sudan,

implementing genuine power-sharing mechanisms as part of peace agreements—such

as the 2018 Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South

Sudan (R-ARCSS)—can help mitigate the political exclusion that often drives

elite rebellion Lijphart (1977).

Gap in the literature

In the study of

political elites' rebellions and their impacts on South Sudan, the literature

often focuses on broad topics such as ethnic divisions, power struggles, and

economic disparities. Many studies

discuss the general consequences of political instability, but few specifically

isolate the impacts of elite-led rebellions on South Sudan's governance,

economy, and social fabric. The hidden impacts, such as psychological trauma,

social disintegration, and infrastructure damage, remain underexplored. Much of

the existing literature addresses the macro-level outcomes, such as

displacement and humanitarian crises, without diving into the micro-level

impacts, such as how elite rebellions disrupt local governance or community

structures. While ethnic loyalty and power struggles are well-researched, more

nuanced motivations such as personal ambitions, access to natural resources,

and the pursuit of economic control are less studied.

How to fill the gap

This study should

focus on the specific less visible impacts of elite rebellions at the community

level. This includes studies on how local governance is affected and the

psychological and social impacts on civilians. Research should expand on elite

motivations beyond the binary ethnic and political narratives, examining how

personal ambition, resource control, and economic disparities drive rebellion.

A comparative study between different regions within South Sudan or between

South Sudan and other post-conflict countries could provide a deeper

understanding of the unique drivers of elite rebellions. This approach would

deepen the understanding of the multifaceted impacts of elite rebellions,

informing more effective peacebuilding and policy interventions.

Research Methodology

Research Design

Garg

and Kothari (2014) describe

research design as the framework for collecting and analyzing data to ensure

relevance to the research purpose while maintaining procedural economy Garg and Kothari (2014). According to Flick (2011), the design influences all aspects of

the research, from data collection to data analysis techniques. This study

utilized a case study design. Data was collected using questionnaires from

individuals working at the study location. The research incorporates both

qualitative and quantitative methods, dealing with numerical data and providing

descriptive analysis. Mugenda and Mugenda (1999)

note that qualitative research aims to provide a detailed, holistic view of

processes, using inductive analysis and emphasizing descriptions over numerical

data. In contrast, quantitative research sought large dataset in producing

generalizable results, using deductive analysis and focusing on discrete

numerical data. Random sampling was employed to ensure the sample was

representative Flick (2011).

Target Population

Ochieng

(2009) defines the target

population as the group of respondents the researcher will interact with. The

target population for this study was drawn from the entire population being

studied. A total of 120 participants was randomly selected to represent this

population, including both males and females from various age groups and

educational backgrounds.

Sample and Sampling Procedures

According to

Orodho and Kombo, as cited by Kombo and Tromp

(2006), sampling is the process of selecting a subset of individuals or

objects from a population so that the selected subset represents the

characteristics of the whole group. Ochieng (2009) explains

that sampling procedures involve selecting respondents from the study area,

which can be done through random sampling.

Sampling size

While the target

population was 120, sample size was

calculated using Taro Yemane formula as given below:

N=N/ (1+N€2) Where

N is the sample

size

N is the

population

E is the margin

error

Target population

= 120

Let the margin

area be at the confident interval of 90%

100% - 90% = 10%,

Where 10% is 0.1

N=120/

(1+70(0.1)2)

=120/ (1+70(0.01))

N=120/

(1+0.7)

120/ (1.7) = 70 Therefore, the sampling size will be 70

respondents.

Research Instruments

Mugenda

and Mugenda (1999) categorize

the information collected in a study as either primary or secondary data.

Primary Data

Primary data is

information gathered directly from the subjects in the sample.

Secondary Data

Secondary data

includes information obtained from articles, journals, newspapers, and other

documented sources. While the researchers collected primary data through

questionnaires, interviews, and observations, secondary data was collected

through books and other sources of empirical literature.

Questionnaires

Bell

(1999) defines questionnaires as

structured techniques for collecting primary data, consisting of written

questions answered by respondents. The researchers used questionnaires due to

their flexibility, allowing respondents time to think and answer without pressure,

ensuring honest responses. They are also economical, facilitating large-scale

and geographically widespread data collection.

Interviews and

Observations

Interviews allow

the researchers to gauge the interviewee's reliability, interest, and

expressions, providing effective and efficient communication of first-hand

information. Observations involve the researchers noting key areas as a method

of data collection. Both of them were used in this study.

Piloting

Piloting helped

identify unclear questions for review. After piloting, unclear questions were

refined for clarity.

Validity and Reliability

Validity

Accurate

Interpretation: The data

should reflect what it is intended to measure. If questionnaires or

measurements are being used, they must target the specific concepts or

variables central to the research. For instance:

Content

Validity: Ensures the

questionnaire covers all relevant areas of the subject.Construct Validity:

Measures whether the tool accurately captures the theoretical concepts.

External Validity: Determines whether the results can be generalized to other

populations, settings, or timeframes. This can be done by distributing

questionnaires to different groups or at different times, and assessing if the

data remains consistent across various settings.Face Validity: Examines if the

instrument appears effective in measuring what it claims to measure, based on

expert judgment. Overall, validity was measured using Content Validty Index

(CVI) which was 0.75, proving that the research instruments were valid.

Reliability

Consistency: a

reliable study produces consistent results under the same conditions. To show

reliability: Test-Retest Method: Conduct the same test or survey multiple times

with the same group, ensuring that results are similar across these trials. Any

significant changes in results may indicate a lack of reliability. Internal

Consistency: If using questionnaires, internal consistency (e.g., using

Cronbach's Alpha) shows if different items within the same test consistently

measure the same construct.mInter-Rater Reliability: When multiple observers or

raters are involved, consistency between their judgments or scores indicates

reliability.By employing methods such as distributing questionnaires across

different times (for validity) and comparing results from repeated trials (for

reliability), the study will demonstrate both accuracy and consistency of its

findings. Given that anything above 0.7 is reliable, the study used Cronbach

Alpha Coefficient (CAC) to calculate reliability. The results read 0.8 which indicated

that the research instruments were very reliable.

Data Analysis Procedures

Ochieng

(2009) describes data analysis

as critically verifying the collected data. Prior to data collection, the

researchers followed university procedures. Both closed-ended and open-ended

questionnaires were designed and distributed to the target population. The researchers

then collected and analyzed using tables and charts.

Ethical Considerations

The study adhered

to several ethical considerations, including voluntary participations, informed

consent, confidentiality of collected data, and communication of results.

Voluntary participation ensured that no respondents were coerced through

misrepresentation or promises of rewards Coolican (2014).

Participants were informed of the study's purpose and asked to voluntarily

participate before their involvement.

Results and Discussions

primary motivations behind the rebellion of political elites in South Sudan

Table 1

|

Table 1 Desire for Control Over Natural Resources

Drives Some Politicians to Rebel |

||

|

Response |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Strongly Agree |

41 |

58.6% |

|

Agree |

18 |

25.7% |

|

Not sure |

9 |

12.9% |

|

Disagree |

1 |

1.4% |

|

Strongly

Disagree |

1 |

1.4% |

|

Total |

70 |

100% |

|

Figure 1

|

|

Figure 1 Desire for Control Over Natural Resources

Drives Some Politicians to Rebel |

Table 1 and Figure 1 shows the respondents' views on whether the

desire for control over natural resources drives politicians to rebel. The

majority of the respondents, 58.6%, strongly agreed with this statement, while

25.7% agreed. Only 12.9% were unsure, and a very small percentage either

disagreed or strongly disagreed (1.4% each). This indicates that most

respondents believe that the desire for control over resources plays a

significant role in political rebellion.

Table 2

|

Table 2

Disagreement Over Governance and Distribution |

||

|

Response |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Strongly Agree |

36 |

51.4% |

|

Agree |

22 |

31.4% |

|

Not sure |

5 |

7.1% |

|

Disagree |

3 |

4.3% |

|

Strongly Disagree |

4 |

5.7% |

|

Total |

70 |

100% |

|

Figure 2

|

|

Figure 2 Disagreement Over Governance and

Distribution |

In Table 2 and Figure 2, 51.4% of respondents strongly agreed that disagreements over governance and distribution are key drivers of rebellion, and 31.4% agreed. Only 7.1% were not sure, while 4.3% disagreed and 5.7% strongly disagreed. This shows that a majority of the respondents support the idea that governance and distribution disputes contribute to political elites' rebellion.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Corruption Within Government Fuels

Discontent |

||

|

Response |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Strongly Agree |

34 |

48.6% |

|

Agree |

18 |

25.7% |

|

Not sure |

11 |

15.7% |

|

Disagree |

3 |

4.3% |

|

Strongly

Disagree |

4 |

5.7% |

|

Total |

70 |

100% |

|

Figure 3

|

|

Figure 3 Corruption Within Government Fuels

Discontent |

Table 3 and Figure 3 highlights that 48.6% of respondents

strongly agreed that government corruption fuels discontent, and 25.7% agreed.

A smaller group of 15.7% were unsure, and only 10% either disagreed or strongly

disagreed. This suggests that the majority of the respondents believe

corruption within the government plays a significant role in causing

discontent.

Table 4

|

Table 4 Lack of Trust Between Rival Political

Factions Contributes to Ongoing Conflicts |

||

|

Response |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Strongly Agree |

44 |

62.9% |

|

Agree |

12 |

17.1% |

|

Not sure |

6 |

8.6% |

|

Disagree |

7 |

10.0% |

|

Strongly

Disagree |

1 |

1.4% |

|

Total |

70 |

100% |

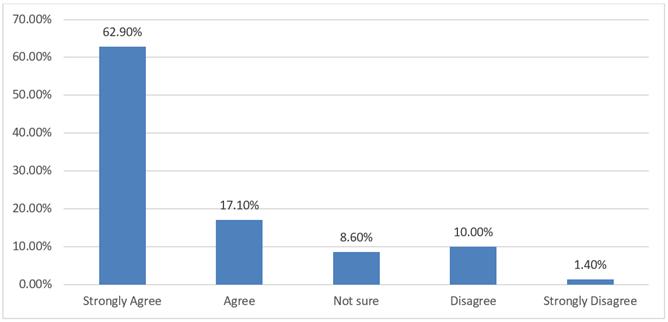

Figure 4

|

Figure 4 Lack of Trust Between Rival Political

Factions Contributes to Ongoing Conflicts |

In Table 4 and Figure 4, 62.9% of the respondents strongly agreed

that a lack of trust between rival political factions contributes to ongoing

conflicts, while 17.1% agreed. Around 8.6% were not sure, and 10% disagreed.

Only 1.4% strongly disagreed. This shows that the lack of trust among political

factions is a widely recognized issue among the respondents.

Table 5

|

Table 5 Socioeconomic Disparities Contribute

Significantly Towards Elite-Led Uprisings |

||

|

Response |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Strongly Agree |

21 |

30.0% |

|

Agree |

21 |

30.0% |

|

Not sure |

14 |

20.0% |

|

Disagree |

10 |

14.3% |

|

Strongly

Disagree |

4 |

5.7% |

|

Total |

70 |

100% |

|

Figure 5

|

|

Figure 5 Socioeconomic Disparities Contribute

Significantly Towards Elite-Led Uprisings |

Table 5 and Figure 5 reveals that 30% of respondents strongly agreed and another 30% agreed

that socioeconomic disparities play a significant role in elite-led uprisings.

About 20% were not sure, while 14.3% disagreed, and 5.7% strongly disagreed.

This indicates a general consensus that socioeconomic disparities contribute to

rebellions, though there is still some uncertainty among respondents.

Table 6

|

Table 6 The Pursuit or Consolidation of Power is

One Key Motivation Behind These Rebellions |

||

|

Percentage |

||

|

Strongly

Agree |

30 |

42.90% |

|

Agree |

26 |

37.10% |

|

Not

sure |

4 |

5.70% |

|

Disagree |

3 |

4.30% |

|

Strongly

Disagree |

7 |

10.00% |

|

Total |

70 |

100% |

Table 6 shows that 42.9% of respondents strongly

agreed and 37.1% agreed that the pursuit or consolidation of power is a key

motivation behind political rebellions. Only 5.7% were unsure, and a small

proportion (4.3% disagreed and 10% strongly disagreed) thought otherwise. This

highlights the strong belief that power dynamics are a driving force behind the

rebellions.

Table 7

|

Table 7 Frustration with Lack of Progress Towards

Peace |

||

|

Response |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Strongly Agree |

33 |

47.1% |

|

Agree |

16 |

22.9% |

|

Not sure |

4 |

5.7% |

|

Disagree |

5 |

7.1% |

|

Strongly

Disagree |

12 |

17.1% |

|

Total |

70 |

100% |

Table 7 indicates that 47.1% of respondents strongly agreed that frustration

over the lack of progress toward peace is a major factor behind rebellion,

while 22.9% agreed. Around 5.7% were unsure, while 7.1% disagreed and 17.1%

strongly disagreed. This suggests that frustration with the peace process is

viewed by many as a contributing factor, though some respondents disagree.

Table 8

|

Table 8 Loss or Displacement of the Civilian

Population |

||

|

Response |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Strongly Agree |

49 |

70.0% |

|

Agree |

12 |

17.1% |

|

Not sure |

1 |

1.4% |

|

Disagree |

5 |

7.1% |

|

Strongly

Disagree |

3 |

4.3% |

|

Total |

70 |

100% |

Table 8 reveals that 70% of the respondents strongly

agreed that rebellion leads to the loss or displacement of civilians, while

17.1% agreed. A small percentage (1.4%) were unsure, and 7.1% disagreed, with

4.3% strongly disagreeing. This indicates that most respondents acknowledge

civilian displacement as a significant effect of the rebellion.

Table 9

|

Table 9 Destruction of Infrastructure and Services |

||

|

Response |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Strongly Agree |

33 |

47.1% |

|

Agree |

25 |

35.7% |

|

Not sure |

1 |

1.4% |

|

Disagree |

6 |

8.6% |

|

Strongly

Disagree |

5 |

7.1% |

|

Total |

70 |

100% |

In Table 9, 47.1% of respondents strongly agreed that

rebellions result in the destruction of infrastructure and services, and 35.7%

agreed. Only 1.4% were unsure, and a smaller group (8.6% disagreed and 7.1%

strongly disagreed) did not agree. This shows that most respondents perceive

infrastructure destruction as a significant impact of political rebellion.

Table 10

|

Table 10 Economic Hardship and Poverty |

||

|

Response |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Strongly Agree |

30 |

42.9% |

|

Agree |

28 |

40.0% |

|

Not sure |

5 |

7.1% |

|

Disagree |

6 |

8.6% |

|

Strongly

Disagree |

1 |

1.4% |

|

Total |

70 |

100% |

Table 10 indicates that 42.9% of respondents strongly agreed and 40% agreed that

rebellion leads to economic hardship and poverty. A smaller group of 7.1% were

unsure, while 8.6% disagreed, and only 1.4% strongly disagreed. This highlights

the widespread belief that rebellion has a major negative effect on the

economy.

Table 11

|

Table 11 Psychological Trauma |

||

|

Response |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Strongly Agree |

25 |

35.7% |

|

Agree |

20 |

28.6% |

|

Not sure |

9 |

12.9% |

|

Disagree |

10 |

14.3% |

|

Strongly

Disagree |

6 |

8.6% |

|

Total |

70 |

100% |

Table 11 reveals that 35.7% of respondents strongly

agreed and 28.6% agreed that rebellions cause psychological trauma. Around

12.9% were unsure, while 14.3% disagreed and 8.6% strongly disagreed. This

shows that the psychological effects of rebellion are recognized, although some

respondents expressed uncertainty or disagreement.

Table 12

|

Table 12 Disruption to Education and Healthcare

Services |

||

|

Response |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Strongly Agree |

31 |

44.3% |

|

Agree |

23 |

32.9% |

|

Not sure |

6 |

8.6% |

|

Disagree |

6 |

8.6% |

|

Strongly

Disagree |

4 |

5.7% |

|

Total |

70 |

100% |

In Table 12, 44.3% of respondents strongly agreed and

32.9% agreed that rebellions disrupt education and healthcare services. A

smaller group of 8.6% were unsure, and 8.6% disagreed, while 5.7% strongly

disagreed. This indicates that a majority of the respondents perceive

significant disruptions in essential services due to rebellion.

Table 13

|

Table 13 Violation of Human Rights Including Abuse

and Exploitation |

||

|

Response |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Strongly Agree |

45 |

64.3% |

|

Agree |

15 |

21.4% |

|

Not sure |

1 |

1.4% |

|

Disagree |

8 |

11.4% |

|

Strongly

Disagree |

1 |

1.4% |

|

Total |

70 |

100% |

Table 13 shows that 64.3% of respondents strongly

agreed that rebellion leads to human rights violations, and 21.4% agreed. Only

1.4% were unsure, while 11.4% disagreed, and 1.4% strongly disagreed. This

suggests that most respondents view human rights abuses as a common consequence

of rebellion.

Table 14

|

Table 14 Social Disintegration Due to Conflict |

||

|

Response |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Strongly Agree |

39 |

55.7% |

|

Agree |

18 |

25.7% |

|

Not sure |

3 |

4.3% |

|

Disagree |

5 |

7.1% |

|

Strongly

Disagree |

5 |

7.1% |

|

Total |

70 |

100% |

In Table 14, 55.7% of respondents strongly agreed and

25.7% agreed that rebellion causes social disintegration. A small group of 4.3%

were unsure, and 7.1% each disagreed or strongly disagreed. This shows that the

majority of the respondents believe that social structures break down due to

conflict.

Table 15

|

Table 15 Negotiations and Dialogue |

||

|

Response |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Strongly Agree |

43 |

61.4% |

|

Agree |

15 |

21.4% |

|

Not sure |

5 |

7.1% |

|

Disagree |

4 |

5.7% |

|

Strongly

Disagree |

3 |

4.3% |

|

Total |

70 |

100% |

Table 15 indicates that 61.4% of respondents strongly

agreed that negotiations and dialogue are important for resolving conflicts,

and 21.4% agreed. Only 7.1% were unsure, while 5.7% disagreed, and 4.3%

strongly disagreed. This suggests that negotiations are viewed positively by

most respondents as a solution to conflict.

Table 16

|

Table 16 Truth-Seeking Processes |

||

|

Response |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Strongly Agree |

25 |

35.7% |

|

Agree |

32 |

45.7% |

|

Not sure |

6 |

8.6% |

|

Disagree |

3 |

4.3% |

|

Strongly

Disagree |

4 |

5.7% |

|

Total |

70 |

100% |

In Table 16, 35.7% of respondents strongly agreed and

45.7% agreed that truth-seeking processes are essential for conflict

resolution. About 8.6% were unsure, while 4.3% disagreed, and 5.7% strongly

disagreed. This shows that truth-seeking is widely supported, though a small

percentage of respondents are skeptical.

Table 17

|

Table 17 Reconciliation Initiatives |

||

|

Response |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Strongly Agree |

37 |

52.9% |

|

Agree |

28 |

40.0% |

|

Not sure |

3 |

4.3% |

|

Disagree |

2 |

2.9% |

|

Strongly

Disagree |

0 |

0% |

|

Total |

70 |

100% |

Table 17 shows that 52.9% of respondents strongly

agreed and 40% agreed that reconciliation initiatives are key to resolving

conflict. Only 4.3% were unsure, and 2.9% disagreed. This highlights that

reconciliation is highly favored as a path to peace among the respondents.

Table 18

|

Table 18 Power-Sharing Agreement |

||

|

Response |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Strongly Agree |

31 |

44.3% |

|

Agree |

19 |

27.1% |

|

Not sure |

9 |

12.9% |

|

Disagree |

7 |

10.0% |

|

Strongly

Disagree |

4 |

5.7% |

|

Total |

70 |

100% |

In Table 18, 44.3% of respondents strongly agreed and

27.1% agreed that power-sharing agreements are necessary for resolving

rebellion-related conflicts. A smaller group of 12.9% were unsure, while 10%

disagreed and 5.7% strongly disagreed. This shows that power-sharing is

considered a viable solution by many respondents.

Table 19

|

Table 19 Security Sector Reform |

||

|

Response |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Strongly Agree |

44 |

62.9% |

|

Agree |

18 |

25.7% |

|

Not sure |

4 |

5.7% |

|

Disagree |

3 |

4.3% |

|

Strongly

Disagree |

1 |

1.4% |

|

Total |

70 |

100% |

Table 19 reveals that 62.9% of respondents strongly