Public Perceptions and Awareness of Climate Change in River Nile State, Sudan: Bridging Knowledge Gaps for Effective Adaptation Strategies

Monzer Hamed 1![]()

![]() , Wafa

Omer 2

, Wafa

Omer 2![]()

![]() , Aisha

Abd-Almoniem 3

, Aisha

Abd-Almoniem 3![]()

![]() , Mona

Mergani 4

, Mona

Mergani 4![]()

![]() , Noura

Mohammed 5

, Noura

Mohammed 5![]()

![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, Environmental Health, Faculty of Public Health/Shendi University,

Shendi River Nile State, Sudan

2, 3, 4, 5 BSc, Environmental Health, Faculty of

Public Health/Shendi University, Shendi River Nile State, Sudan

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Climate change presents significant global

challenges, necessitating a deep understanding of public perception and

awareness to inform effective policies and adaptive strategies. This study

examines the perceptions, knowledge, and concerns regarding climate change

among residents of River Nile State, Sudan, through a cross-sectional survey

of 400 respondents. Most participants were female (79%) and had attained

university-level education (41.5%), factors likely influencing environmental

awareness. Geographic diversity across localities such as Aldamer, Shendi,

and Barbar highlights the importance of localized climate impacts and

adaptation needs. Participants identified terrorism, infectious

diseases, and armed conflict as the most serious threats to human survival,

with climate change perceived as less immediate (mean = 3.10). This

prioritization of socio-political issues over long-term environmental

challenges underscores the need for improved risk communication and public

awareness campaigns. While 81% of participants acknowledged rising

temperatures over the past decade, only 36% were aware of local environmental

policies, revealing a significant gap between climate change awareness and

knowledge of policy responses. Participants reported noticeable climate changes,

including shifts in rainfall patterns (36%) and temperature (18.8%),

consistent with regional climate projections for Africa. Knowledge of

specific climate change drivers varied, with greenhouse gases (mean = 4.3)

and ocean currents (mean = 4.1) being well understood, while aerosols (mean =

3.2) and deforestation (mean = 3.2) were less familiar, indicating a need for

targeted educational initiatives. Air pollution (67.8%) and river pollution (63.5%)

were ranked as the most pressing environmental issues, reflecting concerns

about immediate health and ecological impacts. Temperature fluctuations

(39.8%) and flooding (58.5%) were also considered important. Agriculture,

health, and water resources were identified as the sectors most affected by

climate change, aligning with global findings on exacerbated food insecurity,

water scarcity, and health risks. The study emphasizes the importance of addressing

knowledge gaps and integrating climate change into broader environmental and

development agendas. Public engagement, participatory approaches, and

context-specific adaptation strategies are essential for building climate

resilience. By framing climate change within the context of local concerns

and enhancing public awareness, this study contributes to the development of

inclusive and effective climate adaptation strategies, ultimately supporting

sustainable development and environmental sustainability. |

|||

|

Received 15 January 2024 Accepted 12 February

2025 Published 31 March 2025 Corresponding Author Monzer

Hamed, monzerseta@hotmail.com DOI 10.29121/granthaalayah.v13.i3.2025.5964 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Climate Change, Perception, Awareness,

Adaptation, Sudan |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Climate change represents one of the most profound

challenges of the modern era, with far-reaching implications for ecosystems,

economies, and societies across the globe. The scientific consensus, as

articulated in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports,

underscores the urgency of addressing climate change's causes and consequences IPCC (2014); IPCC (2018)). The impacts of climate change are not uniform; they vary

across regions, scales, and communities, necessitating diverse adaptation

strategies (Adger et al. (2005);

Brooks

et al. (2005). This

variability is particularly evident in vulnerable regions such as Africa, where

climate change exacerbates existing socio-economic challenges, including food

insecurity, water scarcity, and forced migration (Boko et al. (2007); Niang et

al. (2014); Berchin et al. (2017)). Similarly, small island developing states (SIDS)

face existential threats from rising sea levels and extreme weather events,

highlighting the need for transformative adaptation approaches (Mimura et al. (2007); Pelling

and Uitto (2001). Adaptation to climate change is a complex

process that involves not only technological and infrastructural solutions but

also socio-cultural, economic, and institutional dimensions (Smit and Wandel (2006); Klein et al. (2014)). Successful

adaptation requires an understanding of local vulnerabilities, adaptive

capacities, and the broader socio-political context in which adaptation occurs

(Adger et

al. (2005); Conway and Schipper (2011)). For instance, in

Zimbabwe, climate change impacts have been met with varying degrees of adaptive

capacity, influenced by factors such as governance, resource availability, and

community resilience (Brown et al. (2012)). Similarly, in the

Caribbean, the interplay between climate change and water management

underscores the importance of regional cooperation and integrated approaches to

adaptation (Cashman et al. (2010); Campbell et al. (2011)).

Public perceptions and knowledge of climate change play a critical role in shaping adaptive responses. Studies have shown that awareness and understanding of climate risks are key determinants of individual and collective action (DeBono et al. (2012); Glasgow et al. (2018)). However, perceptions are often influenced by socio-cultural factors, leading to diverse interpretations of vulnerability and risk (O'Brienet al. (2007); Thomas and Twyman (2005). For example, farmers in the Limpopo Basin, South Africa, have developed localized adaptation strategies based on their perceptions of climate variability, which may not always align with scientific assessments Gbetibouo (2009). This highlights the need for effective risk communication and participatory approaches to bridge the gap between scientific knowledge and local practices (Eriksen et al. (2011); Wise et al. (2014).

The role of governance and international support in facilitating adaptation cannot be overstated. Official development assistance (ODA) has been identified as a critical mechanism for supporting adaptation in developing countries, particularly in regions with limited financial and technical resources Ayers and Huq (2009). However, the effectiveness of such support depends on its alignment with local priorities and the empowerment of vulnerable communities Denton et al. (2014); Leal Filho et al. (2019). Moreover, the concept of climate-resilient pathways emphasizes the integration of adaptation and mitigation efforts within the broader framework of sustainable development (Denton et al. (2014); Kates et al. (2012). In Africa, the impacts of climate change are particularly severe due to the continent's high dependence on natural resources and its limited adaptive capacity Hulme et al. (2001); Niang et al. (2014). The Fourth Assessment Report of the IPCC highlights that Africa is one of the most vulnerable continents to climate variability and change due to its high exposure and sensitivity to climate hazards Boko et al. (2007). For instance, in Sudan, the sustainable livelihood approach has been used to assess community resilience to climate change, revealing the importance of local knowledge and practices in enhancing adaptive capacity Elasha et al. (2005). Similarly, in Ethiopia, the challenges and opportunities for adaptation are shaped by the country's unique socio-economic and environmental context, underscoring the need for context-specific strategies Conway and Schipper (2011) .In the Caribbean, climate change poses significant threats to water resources, agriculture, and coastal ecosystems (Campbell et al. (2011); Cashman et al. (2010). The region's vulnerability is exacerbated by its geographical location, which makes it prone to extreme weather events such as hurricanes and tropical storms Fontenard (2016). The Caribbean's experience with climate change adaptation offers valuable lessons for other regions, particularly in terms of the importance of regional cooperation, community engagement, and the integration of traditional knowledge with scientific research (Fontenard (2016); Mimura et al. (2007). Public perceptions of climate change are shaped by a variety of factors, including cultural beliefs, socio-economic status, and access to information (Glasgow et al. (2018); DeBono et al. (2012). In Malta, for example, public perceptions of climate change as a human health threat have been influenced by the country's unique environmental and socio-political context, highlighting the importance of targeted risk communication strategies DeBono et al. (2012). Similarly, in developed nations, observed climate change adaptation has been shaped by public perceptions, institutional frameworks, and the availability of resources Ford et al. (2011). The concept of vulnerability is central to understanding the impacts of climate change and the potential for adaptation (Smit and Wandel (2006); Brooks et al. (2005)). Vulnerability is determined by a combination of factors, including exposure to climate hazards, sensitivity to these hazards, and adaptive capacity (Adger et al. (2005); Thomas and Twyman (2005)). In natural-resource-dependent societies, equity and justice are critical considerations in climate change adaptation, as marginalized groups are often disproportionately affected by climate impacts (Thomas and Twyman (2005)). For example, in Sudan, vulnerability assessments have revealed the importance of addressing socio-economic inequalities and enhancing community resilience through participatory approaches (Zakieldeen (2009). Transformational adaptation is increasingly recognized as a necessary response to climate change, particularly in cases where incremental adaptations are insufficient to address the scale and magnitude of climate impacts (Kates et al. (2012); Wise et al. (2014). Transformational adaptation involves fundamental changes in socio-ecological systems, including changes in governance, economic structures, and social practices (Kates et al. (2012). In Africa, for example, transformational adaptation may involve the adoption of new agricultural practices, the diversification of livelihoods, and the strengthening of institutional frameworks to support climate-resilient development Ziervogel et al. (2008); Niang et al. (2014). The role of uncertainty in adaptive capacity is another critical consideration in climate change adaptation Vincent (2007). Uncertainty arises from a variety of sources, including incomplete knowledge of climate impacts, variability in climate projections, and the complexity of socio-ecological systems Vincent (2007). Addressing uncertainty requires a flexible and adaptive approach to decision-making, as well as the integration of diverse sources of knowledge, including scientific research, local knowledge, and traditional practices Vincent (2007); Eriksen et al. (2011).

In conclusion, addressing climate change requires a multifaceted approach that considers the interplay between scientific knowledge, local perceptions, and socio-political dynamics. As the global community strives to limit warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, the need for equitable, inclusive, and context-specific adaptation strategies becomes increasingly urgent IPCC (2018); VijayaVenkataRaman et al. (2012).

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Study Design

A descriptive Cross-sectional community-based study was conducted in River Nile State Sudan, aimed to assess the climate change Perception and Awareness level, of the People of the River Nile State Sudan.

2.2. Study Area

The River Nile state lies in northern, Sudan (32'36° N and

16'22° E) and has an area of 124 000 km2 with a population of about 1 250 000

from different ethnic groups. El Damer, Atbara, Shendi, and Abu Hamad are the

most important cities.

2.3. Study Population, Data Collection, and Analysis

The basic data in this study was gathered through a survey

of 400

persons in the River Nile State, Sudan. A survey questionnaire was designed to

evaluate public awareness and perception of climate change the respondent was

asked to fill out the questionnaire and answer all the questions. The first

part of the questionnaire was about general demographic and personal

information. The second part is climate change-related issues. The respondents

were chosen via random stratified sampling and were interviewed face-to-face.

The purpose of the survey and when the words used in the study have been

clarified to the respondents and kept confidential. Software Statistical

Package analyzed the data for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics 22).

2.4. Ethical Considerations

In conducting this study, all ethical guidelines were strictly followed to ensure the protection and respect of the participants involved. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement in the research. They were thoroughly informed about the purpose of the study, the procedures involved, any potential risks and benefits, and their right to withdraw at any time without any repercussions.

3. Results

Table 1

|

Table 1

Distribution of Participants by Gender, Educational Level, and Locality |

|||

|

Variable |

Category |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Gender |

Male |

84 |

21.0% |

|

Female |

316 |

79.0% |

|

|

Educational

Level |

Primary School |

75 |

18.8% |

|

Secondary School |

133 |

33.3% |

|

|

University |

166 |

41.5% |

|

|

Others |

26 |

6.5% |

|

|

Locality |

Aldamer |

101 |

25.3% |

|

Atbra |

46 |

11.5% |

|

|

Shendi |

98 |

24.5% |

|

|

Barbar |

56 |

14.0% |

|

|

Almatama |

53 |

13.3% |

|

|

Abohamad |

28 |

7.0% |

|

|

Albohera |

18 |

4.5% |

|

|

Total |

400 |

100.0% |

|

Table 2

|

Table 2 Perceived

Threats and Their Severity |

|||||||||

|

Variable |

Least threat |

Minor affect |

Neutral threat |

Major Threat |

Most

serious |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

Percent |

Rank |

|

Terrorism |

39 |

24 |

67 |

251 |

19 |

4.05 |

1.38 |

81% |

4 |

|

Poverty |

57 |

18 |

77 |

183 |

65 |

3.75 |

1.43 |

75% |

4 |

|

Economic

Situation |

48 |

53 |

123 |

66 |

110 |

3.34 |

1.33 |

67% |

3 |

|

Lake of Clean

(Drinking Water) |

39 |

38 |

85 |

183 |

55 |

3.76 |

1.37 |

75% |

4 |

|

Biodiversity

(Habitats)Loss |

63 |

83 |

109 |

36 |

109 |

3.11 |

1.42 |

62% |

3 |

|

Increasing

Population |

89 |

39 |

120 |

66 |

86 |

3.22 |

1.52 |

64% |

3 |

|

Spread

of Infectious diseases |

32 |

33 |

54 |

240 |

41 |

4.06 |

1.34 |

81% |

4 |

|

Armed

Conflict |

35 |

30 |

68 |

217 |

50 |

3.96 |

1.34 |

79% |

4 |

|

Nuclear

weapon |

53 |

28 |

39 |

233 |

47 |

3.95 |

1.47 |

79% |

4 |

|

Climate

change |

56 |

82 |

108 |

74 |

80 |

3.10 |

1.32 |

62% |

3 |

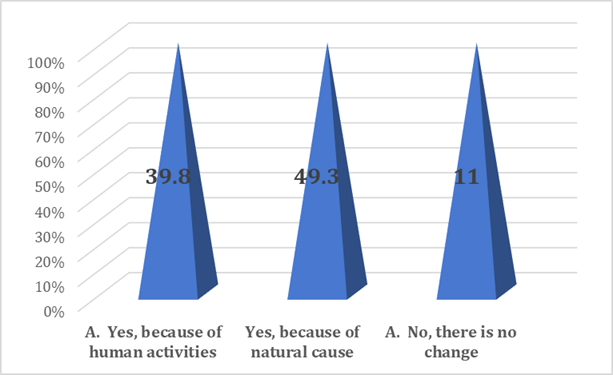

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Demonstrate

Participants That Think the Earth’s Temperature has been Rising over the Past

Decade. |

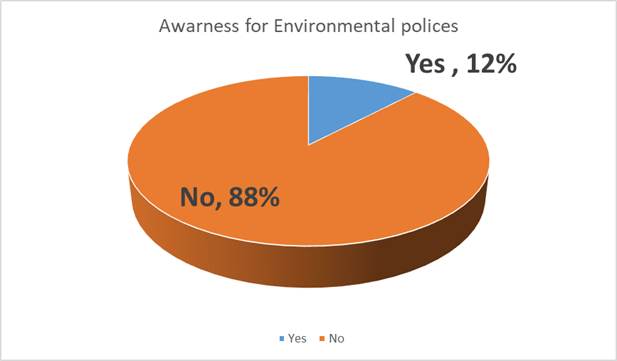

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 Participant

Awareness of the Environmental Policies in River Nile State, Sudan. |

Table 3

|

Table 3 Participants’ Observations of Climate

Changes over the Past 10 Years |

||

|

Variable |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Rain |

144 |

36.0% |

|

Temperature |

75 |

18.8% |

|

Season Shift |

51 |

12.8% |

|

Flood |

88 |

22.0% |

|

Drought |

4 |

1.0% |

|

NO |

38 |

9.5% |

|

Total |

400 |

100.0% |

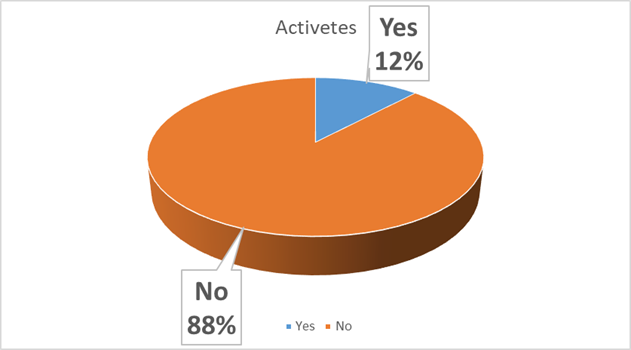

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 Participants

that follow any Climate Change Activities |

Table 3

|

Table 3 Participants’ Understanding of

Climate Change Factors |

||||||||||

|

Variable

|

Don know at all |

Not

broad |

Slightly

broad |

Moderately

broad |

Quite

broad |

Very

broad |

Mean |

Std.Deviation |

Percent |

Rank |

|

Greenhouse

gases |

36 |

30 |

84 |

55 |

25 |

170 |

4.3 |

1.7 |

72 |

5 |

|

Aerosols |

33 |

39 |

75 |

95 |

100 |

58 |

3.2 |

1.7 |

53 |

4 |

|

Currents

in the sea/ocean |

58 |

22 |

88 |

51 |

27 |

154 |

4.1 |

1.8 |

68 |

5 |

|

Melting

of ice or volcanic eruptions |

81 |

44 |

74 |

48 |

129 |

24 |

3.7 |

1.9 |

62 |

4 |

|

El Niño |

58 |

22 |

88 |

51 |

27 |

154 |

4.1 |

1.8 |

68 |

5 |

|

Deforestation |

37 |

57 |

57 |

41 |

121 |

87 |

3.2 |

1.9 |

53 |

4 |

|

Overall,

climate change |

67 |

58 |

135 |

53 |

11 |

76 |

2.9 |

1.8 |

48 |

2 |

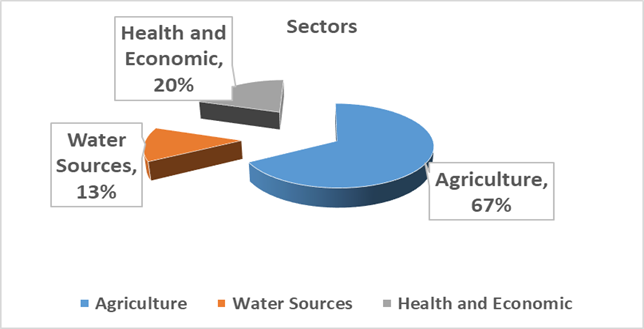

Figure 4

|

Figure 4 Most Sectors

are Affected by Climate Change According to Participant Opinion. |

Table

4

|

Table 4 Perceived Importance of Environmental Issues

among Residents |

||||||||||

|

|

Very Important |

Fairly

Important |

Important |

Slightly

Important |

Not at all

Important |

Mean |

Std.Deviation |

Percent |

Rank |

|

|

Air pollution |

F |

271 |

34 |

42 |

30 |

23 |

1.8 |

1.2 |

36 |

1 |

|

% |

67.8 |

8.5 |

10.5 |

7.5 |

5.8 |

|||||

|

Pollution of

rivers |

F |

254 |

58 |

61 |

27 |

0 |

1.6 |

1.5 |

32 |

1 |

|

% |

63.5 |

14.5 |

15.3 |

6.8 |

0 |

|||||

|

Flooding |

F |

234 |

45 |

63 |

42 |

16 |

1.9 |

1.3 |

38 |

2 |

|

% |

58.5 |

11.3 |

15.8 |

10.5 |

4 |

|||||

|

% |

66.5 |

11.8 |

15.8 |

2.5 |

3.5 |

|||||

|

Poor waste

management |

F |

265 |

40 |

57 |

21 |

17 |

1.7 |

1.1 |

34 |

1 |

|

% |

66.3 |

10 |

14.3 |

5.3 |

4.3 |

|||||

|

Temperature

rise or drop |

F |

159 |

76 |

76 |

65 |

24 |

2.3 |

1.3 |

46 |

2 |

|

% |

39.8 |

19 |

19 |

16.3 |

6 |

|||||

|

Using up the

earth's resources |

F |

224 |

53 |

77 |

31 |

15 |

1.9 |

1.2 |

38 |

1 |

|

% |

56 |

13.3 |

19.3 |

7.8 |

3.8 |

|||||

|

Radioactive

waste |

F |

262 |

43 |

29 |

35 |

31 |

1.8 |

1.3 |

36 |

2 |

|

% |

65.5 |

10.8 |

7.3 |

8.8 |

7.8 |

|||||

4. Discussion

The demographic data

reveals that the majority of participants were female (79%), with a significant

proportion having attained university-level education (41.5%). This gender and

educational distribution may influence the participants' awareness and perceptions

of climate change, as education is often correlated with higher environmental

literacy (Glasgow et al. (2018). The geographic distribution of participants

across localities such as Aldamer, Shendi, and Barbar highlights the diversity

of the sample, which is crucial for understanding localized climate change

impacts and adaptation needs (Boko et al. (2007); Niang et al. (2014).

Participants

identified terrorism, the spread of infectious diseases, and armed conflict as

the most serious threats to human survival, with mean scores of 4.05, 4.06, and

3.96, respectively. Climate change, however, was ranked lower (mean = 3.10),

indicating that it is perceived as a less immediate threat compared to

socio-political issues. This aligns with studies suggesting that public

perceptions of climate change are often influenced by more visible and

immediate concerns, such as health and security (DeBono

et al., (2012); Glasgow et al. (2018). The relatively lower ranking of climate

change as a threat may reflect a need for improved risk communication and

public awareness campaigns to highlight its long-term and interconnected

impacts (Eriksen et al. (2011).

Awareness of Climate

Change (Figures 1 and Figures 2) Figure 1 shows

that a significant majority of participants (81%) believe that the Earth’s

temperature has been rising over the past decade, indicating a general

awareness of global warming. However, Figure 2

reveals that only 36% of participants are aware of environmental policies in

River Nile State, Sudan. This disparity suggests a gap between awareness of

climate change and knowledge of local policy responses, underscoring the need

for better dissemination of information and community engagement in policy

implementation Ayers and Huq (2009); Denton et al, (2014).

Participants

reported noticeable changes in climate over the past decade, with rainfall

(36%) and temperature (18.8%) being the most frequently observed changes. This

is consistent with regional climate projections for Africa, which predict

increased variability in rainfall patterns and rising temperatures (Hulme et al. (2001); Christensen et al. (2007). The reported shifts in seasons and increased

flooding (22%) further highlight the localized impacts of climate change, which

are critical for designing context-specific adaptation strategies (Brooks et al. (2005); Conway and Schipper (2011).

Participants

demonstrated moderate knowledge of climate change-related issues, with

greenhouse gases (mean = 4.3) and ocean currents (mean = 4.1) being the most

understood concepts. However, knowledge of aerosols (mean = 3.2) and

deforestation (mean = 3.2) was relatively lower. This indicates a need for

targeted educational initiatives to enhance understanding of specific climate

change drivers and their impacts (Gbetibouo, 2009; Glasgow et al. (2018). The overall knowledge score for climate change (mean = 2.9) suggests

that there is room for improvement in public awareness and education efforts.

Perceived Importance

of Environmental Issues (Table 4) Air

pollution (67.8%) and river pollution (63.5%) were ranked as the most important

environmental issues by participants, reflecting concerns about immediate

health and ecological impacts. Temperature rise or drop (39.8%) and flooding

(58.5%) were also considered important, though to a lesser extent. These

findings align with studies emphasizing the need to address local environmental

issues as part of broader climate change adaptation efforts Cashman et al. (2010); Fontenard (2016). Climate Change Adaptation in the

Caribbean: Lessons from the Past, Challenges for the Future. Caribbean Studies,

44(1-2), 3-28.. The high importance placed on poor waste

management (66.3%).

Participants

identified agriculture, health, and water resources as the sectors most

affected by climate change. This is consistent with findings from other

regions, where climate change exacerbates food insecurity, water scarcity, and

health risks (Ziervogel et al. (2008); Niang et al. (2014). The recognition of these impacts highlights

the need for integrated adaptation strategies that address multiple sectors

simultaneously Denton et al, (2014); Leal Filho et al. (2019).

The results

underscore the importance of addressing public perceptions and knowledge gaps

in climate change adaptation efforts. While participants are generally aware of

climate change, their understanding of specific drivers and local policy

responses is limited. This suggests a need for targeted educational campaigns

and participatory approaches to enhance public engagement and support for

adaptation initiatives (Eriksen et al. (2011); Wise et al. (2014).

The prioritization

of immediate environmental issues, such as air and water pollution, over

long-term climate change threats highlights the need to frame climate change

adaptation within the context of local concerns. This can be achieved by

integrating climate change into broader environmental and development agendas,

as suggested by the concept of climate-resilient pathways (Denton et al, (2014); Kates et al. (2012).

Conclusion: The

findings from this study provide valuable insights into the perceptions,

knowledge, and concerns of participants regarding climate change and

environmental issues. While there is a general awareness of climate change,

significant gaps in knowledge and understanding remain, particularly in

relation to local policy responses and specific climate change drivers.

Addressing these gaps through targeted education, improved risk communication,

and participatory approaches is essential for building public support for

climate change adaptation and ensuring the effectiveness of adaptation

strategies. The prioritization of local environmental issues further

underscores the need for integrated approaches that address both immediate and

long-term challenges, ultimately contributing to sustainable development and

climate resilience.

These results align

with the broader literature on climate change adaptation, which emphasizes the

importance of context-specific strategies, public engagement, and the

integration of climate change into broader environmental and development

agendas (Adger et al. (2005); Smit and Wandel (2006); IPCC (2014). By addressing the identified gaps and

building on the strengths of local knowledge and perceptions, it is possible to

develop more effective and inclusive climate change adaptation strategies that

meet the needs of vulnerable communities.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

The study revealed a

significant lack of awareness and compliance with environmental regulations

among the residents, with only 12% of respondents being informed and involved

in policy-setting or community-wide policy-sharing. A large majority (89%) of respondents believe

that the earth’s temperature has been rising over the past decade due to human

activities, and 90% have noticed significant climate changes in the State,

particularly regarding rainfall patterns, flooding, and temperature increases.

The rising temperatures and changing

climate conditions are increasingly challenging the viability of agriculture,

industrial plants, and water availability, threatening the overall balance of

the ecosystem.

Initiatives should be undertaken to raise public awareness about environmental policies and the importance of community participation in policy-setting. Educational campaigns and community engagement programs could help bridge the knowledge gap. Efforts should be made to address the public's perception of threats, balancing the focus between immediate concerns like terrorism and the long-term impacts of climate change. This could involve integrating climate change education into broader security discussions. Encouraging greater community involvement in environmental policy-making and dissemination could foster a stronger sense of ownership and responsibility toward climate action and sustainability.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to express my profound thanks to the Public Health authorities for their assistance in data collection. My thanks are extended to all those who helped me in one way or another to finish this work.

REFERENCES

Adger, W.N., Arnell, N.W. and Tompkins, E.L., (2005). Successful Adaptation to Climate Change Across Scales. Global Environmental Change, 15(2), 77-86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2005.03.001

Ayers, J.M. and Huq, S., (2009). Supporting Adaptation to Climate Change: What role for Official Development Assistance? Development Policy Review, 27(6), 675-692. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2009.00465.x

Berchin, I.I., Valduga, I.B., Garcia, J. and de Andrade Guerra, J.B.S.O. (2017). Climate Change and Forced Migrations: An Effort Towards Recognizing Climate Refugees. Geoforum, 84, 147-150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.06.022

Boko, M., Niang, I., Nyong, A., Vogel, C., Githeko, A., Medany, M., Osman-Elasha, B., Tabo, R. and Yanda, P., (2007). Africa. In Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, 433-467.

Brooks, N., Adger, W.N. and Kelly, P.M., (2005). The Determinants of Vulnerability and Adaptive Capacity at the National Level and the Implications for Adaptation. Global Environmental Change, 15(2), 151-163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2004.12.006

Brown, D., Chanakira, R.R., Chatiza, K., Dhliwayo, M., Dodman, D., Masiiwa, M., Muchadenyika, D., Mugabe, P. and Zvigadza, S., (2012). Climate change impacts, vulnerability and adaptation in Zimbabwe. International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED).

Campbell, J.D., Taylor, M.A., Stephenson, T.S., Watson, R.A. and Whyte, F.S., (2011). Future climate of the Caribbean from a regional climate model. International Journal of Climatology, 31(12), 1866-1878. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.2200

Cashman, A., Nurse, L. and John, C., (2010). Climate change in the Caribbean: The water management implications. The Journal of Environment & Development, 19(1), 42-67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496509347088

Christensen, J.H., Hewitson, B., Busuioc, A., Chen, A., Gao, X., Held, I., Jones, R., Kolli, R.K., Kwon, W.T., Laprise, R. and Magaña Rueda, V., (2007). Regional climate projections. In Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, 847-940.

Collins, M., Knutti, R., Arblaster, J., Dufresne, J.L., Fichefet, T., Friedlingstein, P., Gao, X., Gutowski, W.J., Johns, T., Krinner, G. and Shongwe, M., (2013). Long-term Climate Change: Projections, Commitments and Irreversibility. In Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, 1029-1136. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.024

Conway, D. and Schipper, E.L.F., (2011). Adaptation to Climate Change in Africa: Challenges and Opportunities Identified from Ethiopia. Global Environmental Change, 21(1), 227-237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.07.013

DeBono, R., Vincenti, K. and Calleja, N., (2012). Risk Communication: Climate change as a Human-Health Threat, a Survey of Public Perceptions in Malta. European Journal of Public Health, 22(1), 144-149. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckq181

Denton, F., Wilbanks, T.J., Abeysinghe, A.C., Burton, I., Gao, Q., Lemos, M.C., Masui, T., O'Brien, K.L. and Warner, K., (2014). Climate-resilient pathways: Adaptation, mitigation, and sustainable development. In Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, 1101-1131.

Elasha, B.O., Elhassan, N.G., Ahmed, H. and Zakieldin, S., (2005). Sustainable Livelihood Approach for Assessing Community Resilience to Climate Change: Case Studies from Sudan. AIACC Working Paper, 17.

Eriksen, S., Aldunce, P., Bahinipati, C.S., Martins, R.D., Molefe, J.I., Nhemachena, C., O'Brien, K., Olorunfemi, F., Park, J., Sygna, L. and Ulsrud, K., (2011). When not Every Response to Climate Change is a Good One: Identifying principles for Sustainable Adaptation. Climate and Development, 3(1), 7-20. https://doi.org/10.3763/cdev.2010.0060

Fontenard, R., (2016). Climate Change Adaptation in the Caribbean: Lessons from the Past, Challenges for the Future. Caribbean Studies, 44(1-2), 3-28.

Ford, J.D., Berrang-Ford, L. and Paterson, J., (2011). A Systematic Review of Observed Climate Change Adaptation in Developed Nations. Climatic Change, 106(2), 327-336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-011-0045-5

Gbetibouo, G.A., (2009). Understanding Farmers' Perceptions and Adaptations to Climate Change and Variability: The Case of the Limpopo Basin, South Africa. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

Glasgow, S., Brechin, G. and Babbitt, C., (2018). Public Perceptions of Climate Change: A Review of the Literature. Environmental Communication, 12(1), 1-20.

Hulme, M., Doherty, R., Ngara, T., New, M. and Lister, D., (2001). African climate change: 1900-2100. Climate Research, 17(2), 145-168. https://doi.org/10.3354/cr017145

IPCC, (2014). Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC.

IPCC, (2018). Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C Above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty. IPCC.

Jones, R.N. and Preston, B.L., (2011). Adaptation and Risk Management. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 2(2), 296-308. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.97

Kang, S., (2014). Climate Change and Conflict in Africa: A Review of the Literature. African Studies Review, 57(3), 1-22.

Kates, R.W., Travis, W.R. and Wilbanks, T.J., (2012). Transformational Adaptation When Incremental Adaptations to Climate Change are Insufficient. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(19), 7156-7161. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1115521109

Klein, R.J.T., Midgley, G.F., Preston, B.L., Alam, M., Berkhout, F.G.H., Dow, K. and Shaw, M.R., (2014). Adaptation Opportunities, Constraints, and limits. In Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, 899-943.

Leal Filho, W., Balogun, A.L., Olayide, O.E., Azeiteiro, U.M., Ayal, D.Y., Muñoz, P.D.C., Nagy, G.J., Bynoe, P., Oguge, O., Toamukum, N.Y. and Saroar, M., (2019). Assessing the Impacts of Climate Change in Cities and their Adaptive Capacity: Towards Transformative Approaches to Climate Change Adaptation and Poverty Reduction in Urban Areas in a set of Developing Countries. Science of the Total Environment, 692, 1175-1190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.227

Mimura, N., Nurse, L., McLean, R.F., Agard, J., Briguglio, L., Lefale, P., Payet, R. and Sem, G., (2007). Small Islands. In Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, 687-716.

Niang, I., Ruppel, O.C., Abdrabo, M.A., Essel, A., Lennard, C., Padgham, J. and Urquhart, P., (2014). Africa. In Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part B: Regional Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, 1199-1265.

O'Brien, K., Eriksen, S., Nygaard, L.P. and Schjolden, A., (2007). Why Different Interpretations of Vulnerability Matter in Climate Change Discourses. Climate Policy, 7(1), 73-88. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2007.9685639

Pelling, M. and Uitto, J.I., (2001). Small Island Developing States: Natural Disaster Vulnerability and Global Change. Environmental Hazards, 3(2), 49-62. https://doi.org/10.3763/ehaz.2001.0306

Smit, B. and Wandel, J., (2006). Adaptation, Adaptive Capacity and Vulnerability. Global Environmental Change, 16(3), 282-292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.03.008

Thomas, D.S.G. and Twyman, C., (2005). Equity and Justice in Climate Change Adaptation Amongst Natural-Resource-Dependent Societies. Global Environmental Change, 15(2), 115-124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2004.10.001

Tompkins, E.L. and Adger, W.N., (2004). Does Adaptive Management of Natural Resources enhance Resilience to Climate Change? Ecology and Society, 9(2), 10. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-00667-090210

Urry, J., (2015). Climate Change and Society. Polity Press. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137269928.0007

VijayaVenkataRaman, S., Iniyan, S. and Goic, R., (2012). A Review of Climate Change, Mitigation and Adaptation. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 16(1), 878-897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2011.09.009

Vincent, K., (2007). Uncertainty in Adaptive Capacity and the Importance of Scale. Global Environmental Change, 17(1), 12-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.11.009

Wise, R.M., Fazey, I., Smith, M.S., Park, S.E., Eakin, H.C., Van Garderen, E.A. and Campbell, B., (2014). Reconceptualising Adaptation to Climate Change as Part of Pathways of Change and Response. Global Environmental Change, 28, 325-336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.12.002

Zakieldeen, S.A., (2009). Adaptation to Climate Change: A Vulnerability Assessment for Sudan. International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED).

Ziervogel, G., Cartwright, A., Tas, A., Adejuwon, J., Zermoglio, F., Shale, M. and Smith, B., (2008). Climate Change and Adaptation in African Agriculture. Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI). Adger, W.N., Arnell, N.W. and Tompkins, E.L., (2005). Successful adaptation to Climate Change Across Scales. Global Environmental Change, 15(2), 77-86.

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© Granthaalayah 2014-2025. All Rights Reserved.