Passive Instagram use and Emerging Indian female adult wellbeing: A mediation analysis of social comparison and FoMO during covid-19

1 UGC - Senior Research Fellow,

Department of Communication and Journalism, UCASS, Osmania University, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Recent studies in cyberpsychology examined the phenomena of passive Social Networking Sites (SNSs) usage leading to social comparison and thereby leading to FoMO (Fear of Missing Out) George et al. (2019) in general. A review of prior research indicates that for women, but not for males, the relationships between social comparison and FOMO and self-perceived physical beauty were substantial Myers and Crowther (2009).The present study explores the relation between passive Instagram use, social comparison, and FoMO among the Emerging Indian female adults during the covid-19 pandemic. The study focuses on the SNS (Instagram) and its impact on age and gender by undertaking cross-sectional research. It takes into account a diverse sample of college students (N = 302, Mage = 18-25, SD age = between 4 to 5, 100% female). To assess participants' engagement in technology-based social comparisons and feedback-seeking behaviours on Instagram, an 11-item social comparison orientation (INCOM, Iowa-Netherlands comparison orientation scale) English version is used. Social

comparison theory Festinger

(1954) and Symbolic Interactionism are used to explain the study’s

results. The research outcome shows that there is a significant deviation in

the mediation of social comparison and FoMO on the

passive Instagram usage among the Emerging Indian Female Adults during the

covid-19, While the studies conducted before the pandemic show otherwise George et al. (2019). |

|||

|

Received 04 November 2022 Accepted 06 December 2022 Published 31 December 2022 Corresponding Author Santhosh kumar Putta, santoshkera@gmail.com DOI10.29121/granthaalayah.v10.i12.2022.4936 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2022 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Instagram, Social Comparison Theory, FoMo, Female Adolescent Well-Being, Symbolic

Interactionism, Emerging Indian Female Adults |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The Internet penetration rate in India is at 47 percent as of 2021, a consistent increase in internet accessibility compared to 27 per cent five years ago Basuroy (2022). Internet accessibility in India varied on factors like gender and socioeconomic divide. Statistics show that most of internet users are between 20 to 29 years of age and far more male than female users, with the digital gender gap increasing further in rural areas Keelery (2020). A majority of the digital population are mobile internet users due to the availability of cheap data plans owing to the digitisation policy of India India (2015)and increased competition among telecom networks with the entry of jio Infocomm Philipose (2020) in to the 4G data market in September 2016 and emerged as one of the most popular internet-related service providers. This Digital revolution is met with much enthusiasm in India, and social networking sites have become the most widely used internet-based services among the Indian youth. Facebook and Instagram are two of the most popular social media platforms in India. Most of the Indian population uses these platforms, especially millennials and gen Z. In 2018, 73% of Facebook users in India were between 18 and 24 years old Keelery (2020). Instagram is also very popular among young adults, and in 2018 it had more than 80 million users in India. The United States and India jointly head the ranking of most Instagram users, with 140 million users in January 2021 Tankovska (2021).

Societies have always been shaped more by the nature of the media we communicate than by the content of the communication Mcluhn and Fiore (1967). In the age of mobile-mediated communication, SNSs provide an easy and innovative way of communication, like every medium of communication in the past this too has its unique advantages and disadvantages varying in the degree of its impact. The effectiveness of SNS depends on how it is used. Research shows that active social networking use is associated with increased subjective well-being. In contrast, passive SNS use is associated with reduced subjective well-being Verduyn et al. (2015), Prolonged SNS usage can lead to psychological disorders such as Depression, Fear of missing out etc… Burnell et al. (2019).

Research suggests that most young people spend their time on SNS passively browsing the content, such as updates, profiles etc. Tiffeny et al. (2009). Furthermore, we point out mediators of social comparison and FoMO in relation to the effects of passive SNS use on various depressive symptoms and investigate the impact of social networking sites in general and Instagram in particular in the Indian context. This study becomes very significant as the number of Instagram users in India are the highest in the world along with United States of America Keelery (2020).

While India is in the process of catching up with use of internet with the global west till 2019, the covid-19 pandemic has accelerated the adoption of social networking sites and social media, with India and other countries going into lockdown in early 2020, forcing everyone to stay indoors and mobile and computer technologies mediated our personal, professional, and social lives with most of the users with the median age of 27.1 years in India Keelery (2020).

Pre-pandemic research shows social networking users tend to present themselves in a very positive way online Vogel and Rose (2016), This can be problematic for passive SNS users in two ways. First, other posts on social networks can represent positive social events Hu et al. (2014). Passive browsing can therefore lead to the perception that other people have a better social life than you, which can reduce your sense of belonging Ashley and Frances (2018). Second, a person's appearance on social networking sites can be enhanced through filtering and editing. Thus, affecting the self-perceptions of the Passive SNS users, especially in terms of physical attractiveness Fardouly et al. (2015). Exposure to these types of content can be harmful in two ways: a) by evoking harmful social comparisons, and b) by activating feelings of missing out Burnell et al. (2019). The pandemic lockdown has restricted the individuals to their homes, in turn restricting their social life. This current study examines the relation between passive Instagram use, social comparison, and FoMO with psychological well-being and its subscales of the Emerging Indian Female adults during the pandemic who have experienced various levels of FoMO before and after joining the Instagram.

2. The current study

This study examined how passive Instagram use by Emerging Indian Female adult during Covid-19 was associated with social comparison, FoMO, and psychological well-being. In several respects, this study will be a valuable addition to the existing literature in this area. First, this is one of the few studies that tested the pathway between passive Instagram use, social comparison, FoMO, psychological well-being and its subscales. This pathway has been suggested by other researchers for the social networking sites in general Przybylski (2013). Few studies tested it explicitly and followed a similar methodological and the extended study investigating passive SNS use and well-being Kaitlyn et al. (2019). Second, it is one of the few studies investigating passive Instagram usage. Third, A review of previous literature suggests that the pathway from social comparison and FoMO to self-perceived appearance is significant for women, but not for men Myers and Crowther (2009), the study focuses on a specific age group of female Instagram users(Emerging Adults) who are at a crucial and distinct stage of personality development and identity exploration Arnett (2000). Fourth, the study is being conducted during the second wave of theCovid-19 pandemic. It analyses the Instagram usage and mediating roles of social comparison and FoMO and its relation to psychological well-being and its sub scales during pandemic, which makes it an important pandemic study. Fifth, the study investigates how psychological well-being affects the female users who felt FoMO before and after they are on Instagram.

There are multiple

ordering methods for

passive use of

Instagram, FoMO, social comparison,

and psychological well-being. The main hypothesis

is that passive

viewing of content

posted on Instagram by other users may induce fear that other users are

having more rewarding

experiences than one's

the users have, hence Instagram’s use

may induce FoMO.

based on the idea that it can arouse the emotions

of humans Sarah et al. (2017). This allows FoMO to follow Instagram's

passive usage. If

we consider FoMO

as a kind of upward social comparison, FoMO follows social comparison.

A study examining

passive use of SNS found

that once the

process of passive

browsing is initiated, users are typically

expected to go

through the comparison process before making

explicit upward comparisons Burnell et al. (2019). Adverse mental health

effects occur after these upward comparisons

are made.

Alternatively, users with a high level of FoMO can turn

to SNS such as

Instagram for their

connectivity needs of socialization Przybylski (2013), the study investigates both the phenomenon and its impact on

psychological well-being. In turn, lower well-being might indicate depressive

symptoms. The current research looks at the two opposing possibilities in

detail.

H1A: Passive Instagram use positively predicts social comparison, which in turn predicts higher levels of FoMO, which subsequently predicts lower psychological well-being during a pandemic.

H1B: FoMO positively predicts passive Instagram usage, which predicts increased social comparison and lower psychological well-being during a pandemic.

Additionally, previous research suggests that

declining well-being may lead to use of SNS and social media

as a method of mood management (Instagram

browsing, posting, liking,

etc.). Interrelationships between Different Types of Instagram Use and Depressed Mood in Adolescents, 2017). Therefore,

the current study tests

that method as

an exploratory analysis.

H1C: Lower psychological well-being predicts greater passive Instagram use, which predicts increased social comparison and FoMO during a pandemic.

H1D: Social comparison positively predicts higher levels of FOMO, which in turn predicts lower psychological well-being, which subsequently predicts greater Passive Instagram use during a pandemic

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

A convenient sample of 325 female college students

(mostly undergraduates) aged 18-25 took the survey from the

different parts of India during the early 2nd wave of the covid-19

pandemic in the year 2021 (Mage = 20.07, SD age = 1.734, 100% female, 74.9%

urban, 11.3% semi-urban, 13.8% rural). A very

last pattern of 302 college students finished all of the survey items. Respondents

of the survey are contacted through fellow teachers and principals of the

different colleges in India. A survey questionnaire in the form of google form

consisting of demographic, SNS and Instagram usage related questions and

different scales measuring FOMO. Social comparison and psychological well-being

was. circulated in the students' official WhatsApp groups, which are used by

the faculty and management of the colleges for academic communication. Only

measures that are relevant to the current study are reported.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Passive Instagram use

Initially, the participants are asked whether they own a

smartphone or not? Because of the existing gender gap and digital divide,

especially in rural India, followed by whether they are on Instagram? How much

time per day is spent viewing other profiles? Whether they had experienced FOMO

before they were on Instagram? And did the time spent on

Instagram increased due to the pandemic? All the questions are multiple-choice

questions differing in the number of choices. While 97.3% of students owned a

personal smartphone, 2.7% didn’t, 86.5% of female students were on Instagram,

and the same sample is considered for the present study. On average, students passively

browsed Instagram for

105minutes per day.

When asked about whether they have experienced FoMO

before joining Instagram, 39.4% of respondents said yes, 35.6 % said no, while

25% responded with maybe. 78.6% percentage of the respondents agreed that

Instagram usage is increased during the pandemic due to the social

restrictions, quarantines, and government lockdowns. When asked about which is

their favourite social networking site? 70.4% of the respondents said it is

Instagram, confirming the popularity of this particular SNS among the Emerging

Indian female Adults. Even though the present study is unique considering the

pandemic and a specific SNS, the current study's

estimates exceed those

of previous studies,

indicating that young people typically spend

an aggregate of

one hour or more

per day on social media. Shensa et al. (2015).

3.2.2.

Social comparison

A 11-Item Social Comparative

Orientation Scale (INCOM,

Iowa-Netherlands Comparative Orientation Scale) English version is adopted to measure the social comparison among

the Emerging Indian female Instagram users as the Analysis of the data

collected with the scale showed good psychometric properties. It demonstrated

the scales’ ability to predict the comparison behaviour effectively Gibbons and Buunk (1999). Respondents answered items using five-point scale (1: “I disagree

strongly” and 5: “I agree strongly”). The questionnaire is developed following Festinger (1954) differentiates between two distinct dimensions of social comparison: (a) Comparison of

skills on “How

are you?” (Items

1-6) (b)Comparison of

opinions on questions

“what shall I feel/think?” (Items 7-11) Schneider and Schupp (2011).

3.2.3. Fear of Missing out

FoMO among the emerging Indian female Adults was measured using Przybylski (2013) 10- item FoMO scale. Items were answered using a 5-point scale by the respondents (1: “Not at all true of me”, 5: “extremely true of me”). The individual scores to all the items calculated by the averaging responses and form a reliable composite measure (a =.87 to .90) and are currently used as the primary assessment for measuring FoMO in social networking use Burnell et al. (2019).

3.2.4. Psychological well-being

To measure the psychological well-being, 18-item Ryffs scale is used Ryff and Keyes (1995) to assess the psychological well-being of the Emerging Indian female Instagram users during the pandemic. The scale consists of six distinct dimensions of wellness, three questions in each subscale, namely, Self-acceptance (Q1, Q2, Q5), personal growth (Q11, Q12, Q14), Autonomy (Q15, Q17 and Q18), environmental mastery (Q4, Q8, Q9),, positive relations with others(Q6, Q13, Q16), purpose in life(Q3, Q7, Q10). A six-factor model of psychological well-being provides a comprehensive theoretical framework for examining adolescent positive functioning. This study suggests that the theoretical model of Ryffs should be more age-specific and situational in order to better operationalize it Mclellan and Gao (2018). Even though studies have reported inadequate validity and reliability of Ryffs scales, these are widely used in psychology and other interdisciplinary fields to measure psychological well-being. Respondents responded to items using a 7-point Likert scale (1: “strongly agree”, 5: "strongly disagree"). Q13, Q11, Q1, Q2, Q3, Q8, Q9, Q12, and Q17, Q18 are reverse coded using the formula ((number of subscale points) +1) – (respondents answer). Higher scores indicate higher levels of psychological well-being.

4. Analytical approach

We performed a series of path models and mediation analysis using R

software (version 3.6.2,

Lavaan package)

to identify paths between

passive Instagram use,

social comparisons, FoMO,

psychological well-being and combinations of

their dimensions. All

the Emerging Indian female Instagram users who have completed the scales were

included in the models after performing an exploratory analysis of the data collected

(N= 302). Models were specified

using maximum likelihood

estimation and bootstrapping.

5. Results

5.1. Hypothesised Models

To examine

the hypothesis H1A, we tested a mediation pathway model

in which passive

Instagram use predicted social comparison, social

comparison predicted FoMO, and FoMO

predicted psychological well-being Figure 1. Baseline model test statistic is considered as the sample size is

less, the model fit was good, c2(6) = 86.519, p

= .001, CFI =0.998, TFI = 0.994, RMSEA =0. 017, 95%

CI [.000, .117], SRMR = .025. while FoMO(indirect

effect, b = -0.30,

p<0.001) fully mediated social comparison and psychological well-being,

social comparison(indirect effect, b

= -0.03 , p>0.05) did not mediated FoMO and passive Instagram usage among the emerging Indian

female adults, passive Instagram usage has a direct impact on the psychological

well-being(direct effect, b = -0.07 , p<0.001) and has a significant impact on

the subscales of autonomy(direct effect, b

= -0.18 , p<0.001), environmental mastery(direct effect, b = -0.07 ,

p<0.001) and personal relationship with others (direct effect, b = 0.05,

p<0.001) of the psychological well-being.

To examine hypothesis 1B, we tested our mediation

pathway model using

FoMO, which predicts passive Instagram

use, and social

comparison, which predicts psychological well-being. Model

fit was poor, c2(6) = 86.519, p = .001, CFI =0.332, TFI =

-1.005, RMSEA =0. 298, 95% CI [.234, .368], SRMR = .135.

Thus, rejected hypothesis 1B. To test hypothesis

1C, we tested

a psychological well-being

mediated pathway model that predicts passive

Instagram use. It

predicts social comparison and predicts FoMO. To This model fit was

poor, c2(6) = 86.519, p

= .001, CFI =0.912, TFI = 0.736, RMSEA =0. 108, 95%

CI [.044, .184], SRMR = .059.

Descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1. To test

hypothesis 1D, we tested

a social comparison

mediation pathway model

that predicts FoMO. FoMO predicts a decrease

in psychological well-being,

while psychological well-being

predicts an increase

in passive Instagram use. Model fit was perfect, c2(6) = 86.519, p

= .001, CFI =1.000, TFI = 1.021, RMSEA =0. 000, 95%

CI [.000, .104], SRMR = .019. FOMO and psychological well-being

fully mediated the association between social comparison and passive Instagram

usage (indirect effect b = 0.41, p<0.001, via FoMO and psychological well-being b = -0.30, p<0.001). As mediators, FoMO

and Psychological well-being was directly related to adult

women's passive use

of Instagram during pandemic (b = -0.07, p<0.001 and b

= -0.04, p<0.001, respectively): Thus, the results supported the hypothesis

1D.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Correlations and Descriptive Statistics |

|

|

mean

(SD) |

|

|

Passive Instagram usage (min). – PIU. |

104.9(78.89) |

|

Social comparison – SCS |

34.30(5.04) |

|

Fear of Missing Out – FoMOS. |

29.25(8.26) |

|

Psychological well-being – PWB. |

81.45(15.2) |

|

Autonomy. – AU. |

13.85(3.9) |

|

Environmental Mastery – EM. |

13.00(3.85) |

|

Personal growth – PG. |

14.91(4.28) |

|

Positive relationship with others – PRWO. |

12.70(3.71) |

|

Purpose in life – PIL. |

13.24(3.41) |

|

Social Acceptance – SA. |

13.73(4.32) |

|

Note: N=302, *p<.01, **p<0.001 |

|

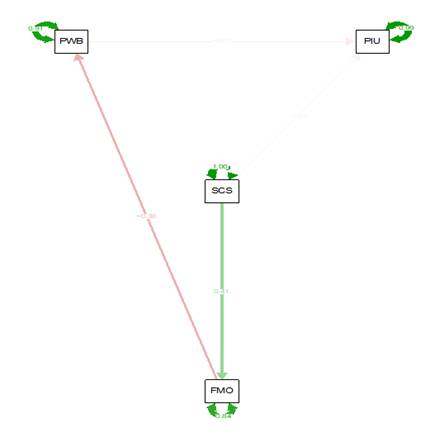

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 c2(6) = 86.519, p = .001, CFI =1.000, TFI =

1.021, RMSEA =0. 000, 95% CI [.000, .104], SRMR = .019. PWB –

psychological well being SCS – Social

comparison FoMOs – Fear

of missing out PIU –

Passive Instagram Use (minutes) |

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 Mediation Path Model for Hypothesis 1D |

6. Exploratory Models

A sensitivity analysis is performed

to test the robustness of the model

presented in Hypothesis

1D. First, the

model was asked to

rate her age (18–25 years), gender

(female), a measure

of passive Instagram use (time spent on passive Instagram

use), and her high-to-moderate

FoMO experience.

Held up when

controlling. We then examined a set of models with constrained and unconstrained equality in multiple

groups by age,

her FoMO experience prior to

joining Instagram, and

passive use of

Instagram to determine the differences between

FoMO subsamples.

I verified the

difference between the

models. The unconstrained model showed a weaker path.

A separate analysis was conducted for passive Instagram usage among the three different groups of people according to the level of FoMO experienced before joining Instagram (PIUOAFY- Users who have experienced high to moderate levels of FoMO before joining the Instagram, PIUOAFM - people who have experienced some level of FoMO before joining the Instagram, PIUOAFN - people who have experienced no FoMO before joining the Instagram, PIUAFY 18_20 – Users who have experienced high to moderate levels of FoMO before joining the Instagram aged between from 18 to 20 years of age), each of these models demonstrated acceptable fit Table 2.

Table 2

|

Table

2 Fit Statistics for the Path

Models Separated by Level of Fomo Experienced

Before Joining Instagram |

|||||

|

|

N |

chi-square |

CFI |

RMSEA |

SRMR |

|

1. |

PIUOAFY |

134. |

c2(6) = 45.128 p<.001. 0.997. |

.022[.000, .174]. |

.035 |

|

2. |

PIUOAFM. |

74. |

c2(6) = 86.519 p<.001. |

.000[.000, .215]. |

.038 |

|

3. |

PIUOAFN. |

94. |

c2(6) = 86.519 p<.001. |

.000[.000, .000]. |

.009 |

|

4. |

PIUOAFY18_20 |

84. |

c2(6) = 30.272 p<.001. |

.131[.000, .284]. |

.067 |

|

Note: All models used the same path model as shown in Figure 1. |

|||||

7. Discussion

Outcomes of the study indicate

that passively browsing Instagram does not predict social comparison; instead

have a direct impact on the psychological well-being of the user during the

pandemic, while social comparison positively predicts High values of FoMO then predict low values

of psychological well-being during. The study extends the previous research Burnell et al. (2019), suggesting that passive SNS usage leads to social comparison, which

predicts FoMO and predicts more significant

depressive symptoms among the SNS users. The study tested the mediation of FoMO and Social comparison among a varied sample of

Emerging Indian female Instagram users, considering the level of FoMO experienced before joining the Social Networking

platform (Instagram) during the covid-19 pandemic.

Social comparison theory Festinger (1954) suggests that people have an instinctive

urge to compare

themselves with others,

even in the absence

of objective information.

Researchers have previously suggested that social

comparison leads to

upward social comparison, which plays an important role in SNS Verduyn et al. (2015) In particular, passively

browsing other users' content on social networks such as Facebook and Instagram can

lead to positive

social comparisons and

negatively affect well-being. The finding of the current research is a particular case

of the suggested path, which examined the impact of passive Instagram usage on

the emerging Indian female psychological well-being during the pandemic; the

current research considerd the experience of FoMO before joining Instagram and studied the mediating

roles of social comparison and FoMO in predicting the

psychological well-being of the Emerging Indian female Instagram user during

the pandemic.

The model tested is consistent

across emerging Indian female Instagram users, which deviates from the path

suggested by the previous research Burnell et al. (2019), validating the mediating roles of social comparison and FoMO on the impact of passive SNS usage on the depressive

symptoms and well-being Verduyn et al. (2015). While Social comparison does not predict passive Instagram Usage among

the emerging Indian female adults during the pandemic, FoMO predicts social

comparison and mediates

social comparison and psychological well-being among

emerging Indian female adults during the pandemic. Secondly, passive Instagram

use negatively predicts the psychological well-being of the user, impacting the

subscales of autonomy, environmental mastery and personal growth, and does not

have a significant impact on the subscales of positive relationships with

others, purpose in life and self-acceptance during the pandemic.

The model was generally consistent across individuals who have experienced moderate to no FOMO before joining Instagram and individuals who have experienced High levels of FoMO before joining Instagram follows a different path model, in which FoMO and social comparison are the mediating factors while the social comparison is causing increased passive Instagram usage among the Emerging Indian Female adults during the pandemic. As the previous research suggests, it is surprising that passive SNSs use leads to social comparison, which does seem to be the case during a pandemic.

Current research points to some limitations. First, the

research is cross-sectional. Longitudinal and experimental

studies are needed to

determine the causality

of the constructs

studied during the pandemic.

Second, a relatively

small, convenient sample size (N = 302) of college students was used, which limited generalization. Third, the presentation

of measures is not

balanced. Therefore, the results may have been influenced by

the order of investigation. Fourth, Instagram

passive usage ratings consisted of open-ended,

self-reported items about

viewing other profiles on Instagram and watching IGTV. Future

research may look at other social networking platforms and

passive use in general, and objectively

assess the use

of Instagram and other

social networks.

Finally, the findings suggest that social comparison does not predict passive Instagram use during a pandemic. In contrast, FoMO positively predicts social comparison and mediates passive Instagram usage and psychological well-being; passive Instagram usage has a direct impact on the psychological well-being of the emerging Indian female adults and has a significant impact on autonomy, environmental mastery and personal growth and does not have a significant impact on the positive relationships with others, social acceptance, and purpose in life during the covid-19 pandemic.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging Adulthood: A Theory of Development from the Late Teens Throughh the Twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469-480.

Ashley, V. W., and Frances, S. C. (2018). Facebook

Undermines the Social Belonging of First Year Students. Personality and

Individual Differences, 13-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.03.043.

Basuroy, T. (2022). Internet Penetration Rate In India 2007-2021.

Burnell, K., George, M. J., Vollet, J. W., Ehrenreich, S. E., and Underwood, M. K. (2019). Passive Social Networking Site use and Well-Being: The Mediating Roles of Social Comparison and the Fear of Missing Out. Cyber Psychology, 13 (3). https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2019-3-5.

Digital and Social Media Landscape In India. (2022).

Fardouly, J. D., Diedrichs, P. C., Vartanian, L. R., and Halliwell, E. (2015). Social Comparisons on Social Media: The Impact of Facebook on Young Women's Body Image Concerns and Mood. Body Image, 13, 38-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.12.002

Festinger, L. (1954). A Theory of Social Comparison. SAGE

Journals. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202.

Frison,

E., and Eggermont, S. (2017). Browsing, Posting, and Liking on

Instagram: The Reciprocal Relationships Between Different Types of Instagram

Use and Adolescents' Depressed Mood. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social

Networking, 20(10), 603-609. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2017.0156.

Gibbons, F. X., and Buunk, B. P. (1999). Individual

Differences In Social Comparison: Development of A Scale of Social Compariosion

Orientation. Journal of Personality And Social Psychology, 76(1), 129-142. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.76.1.129.

Hu,

Y., Manikonda, L., and Kambhampati, S. (2014). What we Instagram. In

Proceedings of the Eight International AAI Conference on Weblogs and Social

Media, 595-598. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v8i1.14578.

India, G. O. (2015). E− Governance, Policy Initiatives Under Digital India. Retrieved From Ministry of Communication and Information Technology.

Keelery, S. (2020). Internet usage in India - Statisics and facts. statista.com.

Keelery, S. (2020). Social media usage in India - Statistics and facts. statista.com.

Mclellan, R., and Gao, J. (2018). Using Ryffs Scales of

Psychological Well Being in Adolscents in Mainland China. BMC Psychology, 6

(17). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-018-0231-6.

Mcluhn, M., and Fiore, Q. (1967). The Medium Is the Message. In M. Mcluhn and Q. Fiore (Eds.), The Medium is the Message. Penguin Books.

Philipose, M. (2020). How Reliance Jio Transformed India's Telecom Industry, In Five Charts.

Przybylski, M. D. (2013). Fear of Mission Out Scale: Fomo. https://doi.org/10.1037/t23568-000.

Quingzhao,

and Bin, L. (2017). Mma: An R Package For Mediation Analysis With Multiple

Mediators. Journal of Open Research Software, 11. https://doi.org/10.5334/jors.160.

Ryff, C. D., and Keyes, C. M. (1995). The Structure of Psychological

Well Being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 719-727. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719.

Sarah, L. B., Jens, F. B., Lucy, R. B., and Jean, D. U. (2017).

Motivators of Online Vulnerability: The Impact of Social Network Site Use and FOMO.

Computers in Human Behavior, 248-255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.09.055.

Schneider, S., and Schupp, J. (2011). The Social Comparison Scale:Testing The Validity, Reliability, and Applicability of the Iowa-Netherlands Comparison Orientation Measure (INCOM) on the German Population. SOEP Papers on Multidisciplanary Panel Data Research, 1-31.

Shensa, A., Sidani, J. E., Lin, L., Bowman, N. D., and Primack, B. A.

(2015). Social Media Use and Perceived Emotional Support Among US Young Adults.

Journal of Community Health, 541-549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-015-0128-8.

Tankovska, H. (2021). Countries With The Most Instagram Users 2021. Statista.Com.

Tiffeny, A., Pempek, Y. A., Yermolayeva, S. L., and Calvert. (2009). College Students' Social Networking Experiences on Facebook. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 227-238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2008.12.010.

Verduyn,

P., Lee, D. S., Park, J., Shablack, H., Orvell, A., Bayer, J., Ybarra, O., Jonides,

J., and Kross, E. (2015). Passive Facebook Usage Undermines Affective

Well-Being: Experimental and Longitudinal Evidence. Journal of Experimental

Psychology. General, 144(2), 480-488. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000057.

Vogel,

E. A., and Rose, J. P. (2016). Self-Reflection and Interpersonal

Connection: Making the Most of Self-Presentation on Social Media. Translational

Issues In Psychological Science, 2(3), 294-302. https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000076.

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© Granthaalayah 2014-2022. All Rights Reserved.