THE TRAINING OF LECTURERS IN THE ECOSYSTEMIC THINKING PERSPECTIVE

Idalberto José das Neves Júnior 1 ![]()

![]() ,

Luiz Síveres 2

,

Luiz Síveres 2![]()

![]()

1 PhD

in Education, Catholic University of Brasilia, Brasília, Brazil

2 PhD in Sustainable Development, Catholic University of Brasilia, Brasília, Brazil

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Current

reality perception can be characterized by different trends, such as the

existential void and social conformism, which in turn impact upon the

educational process. The objective of this study is to suggest a training

process for lecturers in the exercise of the teaching profession in terms of

more cross-sectional and inclusive projects, underpinned by ecosystemic thinking, informed by complexity and transdisciplinarity. The references for this study were

the theoretical precepts of Pensamento Ecossistêmico na Educação (Ecosystemic Thinking

on Education) of Moraes

(2004), the binomial Estímulo Intelectual e Relacionamento Interpessoal (Intellectual Stimulation and Interpersonal

Relationship) of Lowman

(2004), the concepts on the transdisciplinary attitude and the transdisciplinarity of Nicolescu (1996) and Moraes et al. (2014), and the metaphors on the lecturer as a craftsman and an artist

by Axelrod

(1973) and of the Universidade-Semente

(seed-university) and Universidade-Fruto

(fruit-university) by Ribeiro

(1997). The research was based on a higher education institution case

study, performed in the middle of 2019 through a questionnaire and interviews

with eight lecturers, whose contributions were hermeneutically analyzed. The

results highlighted the possibility that good lecturers are those whose

starting point is the presumption of ecosystemic

thinking, integrating individual, knowledge, and agency in teaching. |

|||

|

Received 22 August 2022 Accepted 23 September 2022 Published 12 October 2022 Corresponding Author Idalberto José das Neves Júnior, idalbertoneves@gmail.com DOI10.29121/granthaalayah.v10.i9.2022.4779 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2022 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Training of Lecturers, Ecosystemic Thinking, Exercise of Teaching |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The training of lecturers in their initial academic stages or in the continuous exercise of teaching constitutes a challenge that grows bigger in the course of time and deepens as new generations arrive. This demand may be related to teaching conceptions that do little to integrate the individual, the knowledge, and the acting, ignoring the need for a multi-layered understanding of this situation, of facts that in their turn demand ever-broader perception on the social reality, as well as the cross-sectional understanding of pedagogical processes.

Conjuncture trends directly or indirectly impacting the training of lecturers and their respective teaching exercise seem to be connected with a loss of existential meaning process and, consequently, a disenchantment towards the professionalization. This can be verified on the argument provided by Lipovetsky (2005), stating that contemporary reality is identified as the “era of the void”. Actually, this reality of existential emptiness would be inversely proportional to the diversity of the present technologies and the myriad of available information.

In this context, it is possible to infer the importance of the individuals’ subjectivity and inter subjectivity in their dialogic relations, established through pedagogical processes that prioritize questioning, reflection, and action developed in weaves of learning in a social dynamic that recognizes the importance of interactions and of these individuals’ views towards the learning’s object, as well as of these individuals towards other individuals.

This situation can be confirmed by Castoriadis (2006), who corroborates the previous approach and understands that we are experiencing an “adrift society”, that is, a social project configured by apathy, depoliticization, and privatization, transforming human beings into production and consumption machines, and that humankind is undergoing a period of widespread conformism.

The existential void and social conformism experiences, however, being global trends, do impact local projects and situational procedures. This can be seen on Morin (2003, p. 15) description, stating that educational systems “[...] taught to isolate objects (from their environments), to separate subject areas (instead of acknowledging their correlations), and to dissociate problems, instead of gathering and integrating them.” This observation implies, however, a contradictory educative process, compartmentalized and mechanistic, lacking consideration for the creative, integrative, and entrepreneurial potentiality of the individuals involved in the process of teaching and learning.

Many other features could be incorporated to these, but regarding the cross-sectional questioning, there is a noticeable fragmentation of personal and social relations, disenchantment with social and cultural projects, as well as the partition of teaching projects for lecturers and the partition of the respective teaching exercise. The configuration of these problems points to the question: why does the teaching training process, referring to the ecosystemic thinking, could be suitable for the training of good lecturers?

Numberless initiatives have been performed and various suggestions could be recommended helping to solve this challenge. To meet the goal of this study, which is suggesting a training process for lecturers during their teaching exercise in terms of more cross-sectional and integrative projects and to answer the formulated question, the ecosystemic thinking is being advocated because, according to Moraes (2004), such approach allows establishing personal relations and connections, exercise integrated movements and flows, as well as strengthening self-organized and autopoietic dynamics and procedures in the teaching exercise.

The ecosystemic thinking has as guiding principles the complexity and the transdisciplinarity and can be characterized as a relational and dialogic thinking where everything is connected and interlinked, favouring the praxis of thinking that can transform people’s reality and contribute to the pedagogical training of good teachers.

From this setting on, we intend to establish in the first part a dialog between some formative analogies, subsequently a reflection on the ecosystemic thinking principles, and, finally, based on these presumptions and analysis of collected data, suggest some proposals for the continuous training of lecturers in the exercise of teaching under the ecosystemic thinking perspective.

2. DIALOG AMONG FORMATIVE ANALOGIES

The formative processes prevalent feature is guided by the

separation between training and profession, by the partition between

subjectivity and objectivity, and by the estrangement between theory and

praxis. Aiming at understanding the necessary integration among these

procedures, some formative analogies are the object of reflection, according to

the dialog established between the intellectual stimulation and the

interpersonal relationship, the artist’s ability and the craftsman’s

competence, and the fruit-university spatiality and the seed-university

potentiality.

2.1. THE SUBJECTIVITY BETWEEN THE INTELLECTUAL STIMULATION AND THE INTERPERSONAL RELATIONSHIP

As a rule, the teaching individual is always a relational being.

Yet, in the contemporary context, where formative prevalence is intensely

focused on conceptual aspects, to the advantage of the instrumental rationality

dimension to the point that reason became the prevailing dynamics in teaching

and learning processes, and consequently of the initial and continuous training

of lecturers, it is necessary to reinstate a more cordial and interactive

procedure.

Based on this trend, a Lowman (2004) proposal suggesting as

an educative effectiveness criterion the correlation between the intellectual

stimulation and the interpersonal

relationship is being retrieved. According to the author, lecturers that manage

to establish a dialogic relation between these two procedures are considered more effective and affective with their

students and more productive and significant in the sharing of knowledge.

For this reason, the lecturer’s performance in

intellectual stimulation and their commitment to interpersonal relationship

seem to raise on students’ higher interest in the developed themes and unleash

more significant bonds among the group of academic activities participants.

According to Lowman (2004), such aspects are

founded on the presumption that reason and emotion manifestations motivate

students to do their very best on their activities. Therefore, this dialogic

dynamic would potentialize on the side of intellectual stimulation a higher clarity

on the presented concepts and, on the side of interpersonal relationship, would

be linked to the awareness to understand interpersonal phenomena, thereby

increasing motivation, autonomy, and the desire for learning, thus contributing

to the presumptions of the ecosystemic thinking

through the pedagogical praxis of good lecturers.

2.2. THE PROCESSUALITY BETWEEN THE ARTIST’S ABILITY AND THE CRAFTSMAN’S COMPETENCE

The lecturers formative process, whether in the initial

stage or in the continuous exercise of teaching, is imbued with dimensions

correlated to personal abilities and social competences, which generally are

developed through loose and non-integrated ways. For this reason, we propose to

establish a dialog between these essential dimensions of the teaching demeanor and on the performance of the magisterial

function.

The lecturers formative process, whether in the initial stage or in the continuous exercise of teaching, is imbued with dimensions correlated to personal abilities and social competences, which generally are developed through loose and non-integrated ways. For this reason, we propose to establish a dialog between these essential dimensions of the teaching demeanor and on the performance of the magisterial function.

To characterize a

more theoretical approach, it would be advisable to assume the Axelrod (1973) categorization for ranking teaching professionals. According to the

author, teachers can be described using two categories, the first including

“ways of teaching where questions formulated by the pupil are not required or

encouraged to the fulfilment of the learning established by the teacher. We

call these styles didactic forms” Axelrod (1973, p. 9). The second category is composed by those

who incorporate “ways of teaching where the questioning on the part of the

student is required if he/she wants to successfully perform the task

administered by the teacher. We call these teaching styles evocative forms” Axelrod (1973, p. 10). Referring to this understanding, the author

calls craftsmen those who achieve excellence in the didactic style and artists

those who achieve excellence in the evocative style.

The dialogic between the didactic attitude, understood as craftsman-teacher, and the evocative style, identified as artist-teacher, reveals the opportunity to coordinate these dynamics in complementary and interactive form. Such argument becomes even more explicit because with didactic the craftsman-teacher can be more directed to teach what he/she knows, where the exercise of proposing questions by the learner is not required, emphasizing the instruction and, therefore, revealing a gifted professional in what he/she is willing to achieve. The artist-teacher, on the other hand, is the one gifted with special abilities, with artistic vocation, to interpret roles, to form minds, he/she develops pupils as persons, emphasizes learning and has a high performance on the transformation of people, evoking ways of thinking by means of questioning and inquiring.

The dialog between the craftsman-teacher and the artist-teacher, according to Axelrod (1973), could contribute to the postulation of a formative project that integrates the theoretical foundations and the practical functioning, the educative themes bounded to teaching and learning procedures, as well as to the interactive process between instructing to produce and teaching to think. These postulates can, in their turn, establish a correlation with the interactive and integrative teaching and learning process principles, which supports the presumptions of the ecosystemic thinking, a relational and dialogic thinking that favours the students’ learning and the pedagogical practice of good lecturers.

2.3. THE FORMATIVE SPACE OF A FRUIT-UNIVERSITY AND A SEED-UNIVERSITY

The formative space of teachers and lecturers, whether in

the context of the undergraduate diplomas or in the teaching practice on higher

education schools, is developed within a higher education institution. In the

Brazilian context, such institutions have been much more identified with a

transplanted model than with a locally born and developed model, of tropical features

and energies.

Referring to this perception, Ribeiro (1997), creator of the

University of Brasilia, used the metaphor of the Fruit-University and the Seed-University during his honorary doctorate speech at the

Sorbonne (Université de Paris), in 1978. He then said that one of his greatest

failures, together with the best of what there was in the Brazilian

intelligentsia, was the foundation of the University of Brasilia, as a Fruit-University,

instead of creating a Seed-University,

intended to accomplish an inverse function, as well as of promoting the

Brazilian society’s social and cultural development.

The purpose, according to Ribeiro (1997), was planting in the

capital the headquarters of the Brazilian critical awareness and that all the

human knowledge and revolutionary spirit converged there to accomplish the

single mission that really mattered to the intellectual person among peoples

who failed in history, which was expressing their potentialities through an

interracial civilization, revealing awareness on their destiny as a nation.

Understanding this suggestion and in conformity with this

proposal, the great challenge is to accomplish the transition of still

disciplinary, systematized, and bureaucratic institutions into

transdisciplinary, autonomous, and democratic institutions. At last, without

detracting the Fruit-University that certainly offered humankind much

knowledge, it would be appropriate to potentialize a Seed-University, which

could exercise its originality to develop a

formative process that could coordinate fruit and seed, aspects considered

inherent to institutions imbued with ecosystemic

thinking.

The experience revealed through the three proposed

analogies, together with many other that could be mentioned, will hopefully be

able to formulate a lecturer training process able to establish a dialog

between the sense and meaning loaded experiences through the full-fledged

exercise of intellectual stimulation dimensions and interpersonal relationship, according to

the proposal of Lowman (2004); that it could

facilitate a coordination among the performance of training process, informed

by Axelrod (1973)

theoretical precepts, so that they can become education artists and craftsmen

through the development of abilities and competences, and that it will be

possible to provide the educational institutions with coordinating projects

between a fruit-university and a seed-university. Such procedures can

contribute to the understanding of the ecosystemic

thinking and its practical consolidation, understanding the proposed analogies

as capable ways of causing transformation on the course of the lecturer’s

training development and in the exercise of the teaching profession.

3. PRESUMPTIONS OF THE ECOSYSTEMIC THINKING

The presumptions

of the ecosystemic thinking can hypothetically

contribute to the lecturer’s training process in the consideration and in the

practice of the teaching activity. From this understanding on, it is possible

to infer that transdisciplinary teaching is complex in its

epistemological nature, understood here as a fundamental feature for a better

comprehension of relations, connections, and emergencies that take place in the

educational environments Moraes et al. (2014). For this reason, resumption and targeting of some ecosystemic

principles are advised, having as presumption a dialogic relation between

complexity and transdisciplinarity.

The fact that ecosystemic thinking is based on complexity and transdisciplinarity potentializes the acknowledgment of mutual, simultaneous, and recurrent interactions between the subjects

and their environment, between learners and teachers, individuals and contexts,

reason and emotion. This perception also includes acknowledging

the existence of relational dynamism among individuals, between individuals and

culture instruments, between individuals and their belief systems,

organizations, and ways of thinking and doing Moraes (2004).

3.1. THE DIMENSIONS OF ECOSYSTEMIC THINKING

Under the presumptions of complexity and transdisciplinarity, the dimensions of ecosystemic

thinking constitute an integrated and integrative weaving, however, to

understand its contribution they are described in their singularity, even if

forming a systemic process. As a theoretical anchor of this paradigm,

there are the precepts of ecosystemic thinking, based

on ontological, epistemological, and methodological dimensions, according to Moraes and Valente (2008).

The ontological dimension of the ecosystemic

thinking encompasses a dynamic, diffuse, relational, undetermined, and

nonlinear, continuous/discontinuous, and unpredictable dialogic reality.

However, in this reality of contraries’ unity, a dynamic of the come-to-be

prevails over the ways of being, and, therefore, the reality constructed by the

relation subject/object must be multidimensional, integrating the different

levels of reality, a reality that emerges as integrated totality,

configuring a global, complex, integrated, interactive, and participative

unity. Thus, the essence of the being is formulated in his come-to-be,

integrated to the historic reality and to the binding process of the subjects’

thinking and action.

Subsequently, the epistemological dimension is guided by

the constructivist and interactionist configuration and founded on the

dialogical intersubjectivity, which generates a complex epistemological base

implying on the acceptance of the multiple and diverse nature of the studied

subject and object, involving a nonlinear dynamic and, therefore, dialogic,

interactive, recursive, and open. At the same time, it redeems the human

knowledge bio-, psycho-, and sociogenesis and, therefore, subject and object

are inseparable and interdependent because the presence of intersubjectivity is

indicative of the impossibility of a purely objective knowledge, for there is

always an object in relation to a subject that observes and thinks,

highlighting the mechanisms of interrelation, of self-organization, and of

self-ecological organization.

At last, the methodological dimension shelters the

prevalence of qualitative methods, but without denying the complementarity of

quantitative ones, provided that there is theoretical

and methodological compatibility. The method is understood as open, adaptive,

and evolutionary knowledge’s action strategy, and acknowledged as a way

discovered during the journey, constructed step by step, tributary of

bifurcations, retrospections, deviations, and recursions. By this token, the

method underpinned on complex causality indicates the need of open, flexible,

dynamic, and revisable procedures, using multi-methods; however, having

uncertainty as a permanent feature of the scientific search and construction.

Nonetheless, these dimensions constitute a dynamic that

propels the acknowledgment of the ecosystemic

thinking basic presumptions, which are complexity and transdisciplinarity,

both having impacts on the educational project.

3.2. THE ECOSYSTEMIC THINKING INFORMED BY COMPLEXITY AND

TRANSDISCIPLINARITY

The ecosystemic thinking

presumption is connected to complexity and transdisciplinarity

inserted in the phenomenon of life, which is by itself inconclusive and

complex, being in permanent transformation and inserted in a dynamic that we

grope without entirely seeing it.

In such an approach, the theory of complexity views the

subject in its integral form, demanding the reintegration of the whole, which

allied to teaching requests a radical change of both unitary and connected,

relational and collaborative knowledge, essential precepts to the ecosystemic thinking exercise.

In the theory of complexity, the disjunctive thinking is

changed into integrative, with a view of the whole, of networks, and

interconnections. The instability, the unfinished, and the man’s conscious

intervention to transform this time or environment are acknowledged. Through

intersubjective presumption, the acknowledgment of the other takes place, due

to the multiple versions, and to a plural reality simultaneously analysed by

different findings.

Under such complexity it is possible to approach D'ambrosio (2009) triangle of

life—individual, nature, and society—and determine which would be the

possibilities to integrate activities, enlarge the time to learn, use the

available space for different and new educational explorations, respecting the

pupils’ needs.

Moraes (1997) affirms that the

educational phenomena must be perceived as processes, in the complexity of

their interrelations, being at the same time determinants and determined, in

movement and permanent state of change and transformation, in relation to the

principles of uncertainty and complementarity.

The quantum

physics principles, Werner Karl Heisenberg’s uncertainty and Niels Bohr’s

complementarity, rephrased the epistemological question of science because they

rescued the role of the subject, of the scientific observer in all processes,

resulting in implications to the philosophy of science and to education Moraes (2015).

These principles

are present in the ecosystemic thinking, which is

nurtured by complexity and many other principles capable to coordinating,

integrating, and reconnecting processes, phenomena, and facts Moraes (2020) among them transdisciplinarity.

For Nicolescu (1996), transdisciplinarity

is that thing that happens to be located between disciplines, through them, and

even beyond them, when encompassing the world, whose imperative would be the

unity of knowledge. For Torre et al. (2008), transdisciplinarity

presents three core conceptual areas: scientific, epistemological, and

methodological knowledge construction; greening—or “ecologized”—action;

and transdisciplinary attitude.

In relation to

this transdisciplinary attitude and to transdisciplinarity,

here follows a conceptual synthesis of such reflections Moraes (1997, 2004, 2008, 2015 ); Moraes et al. (2014); Moraes and Valente (2008); Torre et al. (2008).

Transdisciplinary willingness is what enables us to

address a transdisciplinary action, a daring manner, and a quest for knowledge.

It is an attitude towards the alternatives to know more and better, which

propels exchange, dialog with oneself and with the other, a humble approach

towards the limitation of the being, a form of challenge in front of the new,

it is an attitude of searching new accesses to reality and it is an action that

searches intelligibility, it is an epistemological attitude that promotes the

partnership and integration of what happens on different levels of reality.

Transdisciplinarity searches for

knowledge unity, but not through the reduction of the real to a reading, to a single

reading, as mathematization, or the formalization of knowledge, which in

traditional thinking means everything that must come to that single reading.

This quest has its way through the possible dialog among the different reality

dimensions, which are the different knowledge areas. For this reason, we depart

from disciplinarity, always recognizing disciplines as something extremely

important to the understanding of reality in order to

arrive at transdisciplinarity.

With this approach transdisciplinarity

presents the existence of levels of reality because all knowledge is

complementary, non-fragmented and inseparable and including the logic of the

third, where contrary propositions may also be true because connected to Niels

Bohr complementarity principle, breaching the dualistic thinking to capture

levels of reality excluded by classical thinking, and even open to

spirituality.

Thus, there is another complexity category that allows

capturing the inter-, intra-, and trans-relations, which exist among the

various levels of reality, a plural unity of knowledge for us to understand and

work the reality. It all opens to the dialog of findings to comprehend and

construct another possible world, founded on cultural diversity, on the

co-evolution of cultures, and new awareness, respecting differences. With this

referral, transdisciplinarity can promote

reconciliation between the subject-object, between the exterior and interior

man, in an attempt to recompose the different

fragments of knowledge.

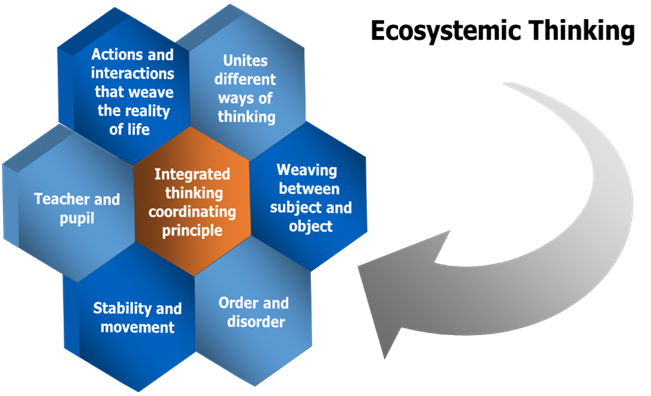

This ecosystemic thinking approach, based on complexity and transdisciplinarity, configures a thinking coordinating principle by means of the union of different ways of thinking, of the weaving between subject and object, of order and disorder, of stability and movement, of the relation between teacher and pupil, and of the integrated actions that weave the reality of life, as Figure 1 demonstrates.

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Source Constructed from Moraes (2004) Ideas |

The figure reveals, therefore, the ecosystemic thinking integrative principle matricially coordinated, with distinct educational possibilities, revealing the systemic dynamics that, in this case, is always complex and transdisciplinary. As in a field of possibilities, it is with such an approach that the understanding of the training of lecturers in the exercise of teaching is intended, having the ecosystemic thinking as presumption.

4. THE TEACHERS’ TRAINING IN THE CONSTRUCT OF ECOSYSTEMIC THINKING

From the theoretical description, a case study was

performed, and the survey took place in a communal and confessional higher

education institution that during the research was organized in knowledge areas

through schools. For the understanding of the research object it was requested

to these schools’ directors the indication of five (5) lecturers that they considered good educators according to

the following qualities and competences: excellent evaluation by pupils; those

recurrently praised by pupils; those who develop concepts and/or innovative

incentives involving pupils on learning processes; involvement on the

development of new degrees, laboratories, or curriculums; creativity and impact

on pedagogy and/or applications in the development of classroom or hybrid

trainings. Subsequently, a questionnaire was sent to 6,560 students of 47-degree

programs, which formed the local base of students in Dec. 2018. 1,0009 students

of 37-degree programs answered and the results confirmed almost exactly the same names indicated by school directors. This

instrument to collect data demanded from students indicating the best lecturer

of their undergraduate courses and the identification of up to three (3) names

of lecturers considered unforgettable because of their particular

form of intellectual stimulation and relationship with students, of

establishing the dialog between the artist’s ability and the craftsman’s

competence, or the attitude linked to knowledge, whether if more as a seed than

as a fruit.

Based on this information, a half-structured interview was

performed with 8 lecturers in the period between June and August 2019 on their

reflections and teaching practices, considering that both directors as well as

students coincided in this indication. To keep confidentiality regarding the

identification of these lecturers, they were identified with the letter P and

the numbers 1-8 for each participant.

The selected lecturers were interviewed based on

ontological perception, epistemological reflection, and methodological

practice; all respective contributions were hermeneutically analysed according

to Schleiermacher

(2010), Gadamer

(2009), and Dilthey (2010), with the objective of

understanding what they were reporting according to the informed categories,

which are described and analysed from the interviews and the ecosystemic thinking theories, as well as connected to the

analogies that introduced such reflection.

CATEGORY 1 –

ONTOLOGICAL FORMATION

For the ontological formation category, it is recommended

prioritizing the analogy of Lowman (2004), which suggests the

dialog between the intellectual stimulation and the interpersonal

relationship. In this context, it is important to stress that the ontological

dimension—the one of the beings—was prevalently reported, as well as the terms

love, joy, assist the other, empathy, and otherness, both based on theoretical

references as on considerations presented by the lecturers, what may indicate

the importance of this dimension to the training of good lecturers.

In relation to the

theoretical foundations of the ecosystemic thinking Moraes (2004, 2020) applied to the outcomes of the analysis

performed on the interviewed lecturers’ vocation, it is possible to

infer—resorting to theoretical perspectives of this thinking—elements able to

clear the findings regarding the characterization of a good lecturer, for

example, with the terms accepting the other, develop autonomy, establishing an

ecology of findings, exercise empathy, otherness and solidarity, and conducting

the practice with ethical principles. This reveals that such lecturers treat

students as human beings, loaded with historicity and experiences that must be

considered for the students’ education, where each individual

is constructing his/her history, experiencing and developing possibilities of

learning.

Demonstrating love for students is an important factor for

potentializing the students’ learning, establishing an environment of

instigation and intellectual stimulation, constituting a field packed with

educational possibilities. The relationships of lecturers with students are

preferably guided by the exercise of empathy and recognition of otherness.

The interviewed lecturers demonstrate respect for students because they consider students in their individual differences. These lecturers’ way of acting results in an attitude that favours the development of adequate and satisfying interpersonal relations as well as optimizes intellectual development. Such attitudes of the interviewed are embodied from the transcription of some excerpts of the interviews.

Above all, I do not have a biologist with me, I have a

human being like me (P1).

[...] sacred is

what each person believes in, has faith in. In my conception, I believe a lot

in each one’s sacred and that we have to respect the

sacred of everybody, which you have learned since your childhood [...]. [...] I

look for respecting this conception [...] (P5).

The demands of teaching, the demand of practice becomes

softer because my concern is not the technique, it is knowing if I am

developing a good human being (P7).

[...] I think the

most important for constructing this pathway is receptivity, is to avoid

embarrassing the student, or judging his questions, or answering that his

question belongs to a different discipline or that ‘we shall see’ [...] (P6).

[...] it’s been

almost ten years teaching the same discipline and each group has a singular

dynamic, each class has its own kind. [...]. Maybe first and above all, respect,

and invitation. From there on, perhaps things may develop well (P8).

Analysing these reports highlight, in a prevalent way, the

dialog between intellectual stimulation and interpersonal relationship,

according to the Lowman (2004) analogy, as a

fundamental condition of life and possibility of relational bonds, the

acceptance of a plurality of approaches, views, and understandings, openness to

ideas and to solidarity in the search for the others’ participation and

collaboration, solidarity, and love as ways of dealing with one another.

It is possible to deduce that the student forms his own

identity with liberty and autonomy, reaching self-awareness, and that the

dialog is exercised as a possibility of relational bond, that the spaces of

learning are conceived in an ecology suited to liberate ideas, that solidarity

and otherness increase students inclusion on educative processes and that

legitimate demonstration of cooperation, solidarity, and love stimulate

learning, according to Moraes (2004), having as reference

the ecosystemic thinking.

Additionally, the reports allow inferring the importance

of dialog as fundamental life condition and for the establishment of a relation

bond, of the sense of solidarity and cooperation for the students’ inclusion,

of the demonstration of love to the student favouring the development of

learning and the correction and right answering in the light of good living

ethical principles, bringing joy and curiosity to the places of learning.

Having as presumption the ecosystemic

thinking, and in order to configure the lecturers’

training process, the ontological proposal would be strongly guided by the

integration between the teacher’s relational attitude and the intellectual

activity of the lecturer. That is, human affection and epistemological

affection would be the dynamics recommended for the training of lecturers in

the exercise of teaching.

CATEGORY 2 –

EPISTEMOLOGICAL REFLECTION

The epistemological category would be more connected to

the analogy of the seed-university and the fruit-university. Thus, according to

Ribeiro

(1997), the Brazilian

knowledge construction process occurred mainly approaching the fruit in

detriment of a seed characterized thinking. Such aspect can still be observed

in the current context, primarily in the creation and approach of sciences.

This can be perceived both in literature as in the

lecturers’ explanations, while indicating a way of organizing knowledge and how

they can make the difference in the students’ learning. These approaches can be

perceived as one tries to search learning strategies according to the students’

needs, and for that lecturers must support the student during the pathway of

his/her learning, dealing with errors as possibilities to verify what is

pending, demonstrating the importance of initial planning for the execution of

classes, stressing the relevance of the contents’ sequential chain for learning

retention, using digital technologies as learning artifacts, and exercising

interdisciplinarity.

It is possible to infer from these perceptions that

intimacy with contents and the loving feeling that a lecturer has for his or

her knowledge area are elements that add to the effectiveness of the student’s

learning. These ways in which lecturers organize knowledge were outlined from

some interviews and are described in sequence.

This is a great challenge because I see many students

coming with a very fragmented view, so we really have to

perform a construction of it along the semester, it is not something that will

happen in the blink of an eye, it is a construction process (P2).

[...] do not attach

do much to the content in the sense of getting constrained in it, but adding

components of others, it has a nice aspect, an economical aspect, and sometimes

you capture a pupil in it [..] you capture through interdisciplinarity [...]

(P6).

What I have today as educational background inside botany

allows me certain comfort, I can transit among knowledge areas and integrate

them relatively easily (P1).

[...] I think it

takes a very big identity and a detail I perceive and talk a lot about is the

love for knowledge, your passion for the discipline grows as you deepen this

knowledge [...] (P6).

Whenever you get restricted to some knowledge, you have

various distinct effects on the student, he gets bored with that, he loses

interest, and it can even result in discouragement towards his learning (P3).

[...] you notice that the students are in a process and

that they already understood, they already noticed this critical view that they

must have on language itself and of language in a general way (P4).

It is possible to infer from the interviewees reports that intimacy with contents and the loving feeling that a lecturer has for his or her knowledge area are elements that add to the effectiveness of the student’s learning, configuring a seed-thinking. The search for learning that demonstrates a holistic form, the understanding of phenomena in its entirety and globality, and the lecturer’s affection for the knowledge area that transcends applicability to the solution of problems are also facts that can be stressed from these reports.

These reports

emphasize that the pedagogy developed by lecturers highlight the dialog

exercise for the establishment of a relational bond, that didactic situations

are always underway, allowing the construction of new possibilities, the

development of a mutual belonging awareness in a learning environment both

collaborative and liberating for ideas, what brings sense and significance to

learning, the complementarity of processes and approaches that favour the

development of inter- and transdisciplinary methodologies Morin and Moigné

(2008), and transcendence, allowing the achievement

of a new evolutionary stage in the students’ learning.

These reports emphasize the didactic strategies as essential artifacts to learning effectiveness, where the lecturer must achieve a certain level of awareness regarding the contents planning and the execution of classes, which in front of emergencies should be adjusted to the needs of the context and of the students.

The possibility for the epistemological category to be characterized as an inductive element of dynamics in the training of lecturers in the exercise of teaching constitutes a fundamental aspect. However, the mere transmission of knowledge (fruit) must be replaced in order to unveil creative and interactive processes (seed), so that knowledge potentializes new forms of learning.

CATEGORY 3 –

METHODOLOGICAL PRACTICE

The methodological practice category may be closer to the

analogy proposed by Axelrod (1973), as he suggests

coordination among the artist’s ability and the craftsman’s competence. To

compose methodological practice, both literature as lecturers inform

methodological strategies that can contribute to the effectiveness of students

learning, such as: having in mind what it is essential, namely to take to a

space of learning connections, relations, and associations that require from

students the search for new possibilities as the learning progresses; enable an

ecosystemic view so that the student is able to

connect, relate, and interpret; search practices that present contextualized

knowledge, adding to learning effectiveness; evaluate the whole learning

process, issuing feedbacks, praising students assertions and the construction

of a critical view on the educative processes; providing students support, so

that they understand the content and do not lose interest and motivation; have

the application of contents and human relationships as guidelines; define

processes that prioritize interaction between lecturer and students and among

students; and encourage students to perform searches and to connect other

information departing from their reality.

These indicators highlight that the methodology developed

by the lecturers emphasizes dialog for the establishment of a relational bond

and that didactic situations are permanently kept in progress, allowing the

construction of new learning possibilities, bringing sense

and meaning to the educative project through the complementarity of procedures

and approaches, favouring the development of methodologies that allow a new

evolutionary stage in the students learning.

Referring to some lecturers’ reports, such approaches were identified and are presented below.

[...] we have laboratory classes, which associate practical activities and theory [...] it is very common and frequent that we see (observe) departing from knowledge and then shortly after the students manage to experience it while practicing (P1).

[...] I assess the whole process, but there is a final stage—when the text is rewritten—that I say is the process's most important part. [...] feedback on what he has produced, of the reflections he has made and on how he is using language (P4).

[...] when they are on-site, they notice that there are various problems and that the methodology could seem fantastic, but they face situations demanding solutions that they will have to find by themselves (P2).

[...] I will use the whole class to explain and prompt them to think, reflect, and question in a certain sense (P6).

We come with an array, and this array multiplies as the semesters flow, and we get to know the group itself and the course dynamics. And I think diversification is what brings the greatest possibilities (P8).

[...] the personal attitude of living with the differences, respecting, comprehending it in a positive way and incorporating it for life, for I think that is the university’s role: to transform people, I mean it in the sense that the person who gets in here must get out in a better shape, and achieving it is the lecturers’ role (P7).

The analysis of these reports demonstrates that the lecturers’ proposed methodologies allow the construction of the student’s own identity with liberty and autonomy, stimulating them in terms of participation, solidarity, equality, and diversity, as well as to establishment of exchanges, symbiosis, and retrospections in a self- and ecologically organized procedural dynamics where dialog develops an essential role to the relation bond.

Therefore, the learning context is an affective, cultural, and ecological psychosocial setting, where transformation and the interaction of numberless factors take place to favour the development of an educational process in a contextualized way. Thus, knowledge and learning construction processes are developed through interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary perspectives, enabled by a plurality of focal points and particular views to promote the exercise of solidarity and otherness.

Through the

presumption of the ecosystemic thinking Moraes (2004, 2020), the data analysis under ontological,

epistemological, and methodological views highlights that the interviewed

lecturers’ ways of being, thinking, and acting encompass all the theoretical

elements of this paradigm, enabling—in these perspectives’ attributes form—the

disclosure of a training process for outstanding lecturers in the exercise of

teaching.

5. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Acknowledging the importance of the ecosystemic thinking in the contemporary educational context is enabling the understanding and the formulation of a training process in conformity with the current reality’s weaves and uncertainties. From this perspective, ecosystemic thinking might prove adequate and intrinsically able to help with going beyond a standardized reality, introducing creative, significant, and innovative aspects.

Thus, the lecturers’ training in their continued teaching education stage remains a challenge because the dualistic comprehension between reason and emotion, craftsman, and artist, or between seed and fruit, according to the presented analogies, remains very evident. However, the possibility of overcoming this dualism and proposing more dialogical dynamics might be accomplished considering the alternative of the ecosystemic thinking.

Thus, having the ecosystemic thinking as cross-sectional dynamics, the formative proposal formatting would have to be exercised through complexity and transdisciplinarity, preferably encompassing the ontological, epistemological, and methodological dimensions, which are aspects that require integrative, complementary, and holistic dynamism because of the involvement of the existential disposition (be), the sapiential reflection (know), and the attitudinal commitment (act).

Besides, the interviewees' understanding can help to highlight the perception that lecturers who are considered good professionals—whether by students or school directors and regardless of their scientific areas—achieve such a result as they manage to coordinate the lecturer as a human being with the exercise of teaching having as a presumption the ecosystemic thinking.

Therefore, suggesting a lecturers’ training process in their continued exercise of teaching requires dialogical dispositions between the lecturer as a human being and his professional acting; the dialogic reflection between the accumulated experience and the prospect of constructing knowledge, and additionally that such process should go on a pilgrimage among active, reflective, and propositional methodologies aiming at adding to the training of ethical people, skilled professionals, and education committed citizens.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Federal District Research Foundation (Fundação de Apoio à Pesquisa do Distrito Federal - FAP/DF).

REFERENCES

Axelrod, J. (1973). The University Teacher as Artist. San Francisco. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.36919730105

Castoriadis, C. (2006). Uma Sociedade a Deriva: Entrevistas e Debates 1974-1997. Aparecida, SP.

D'ambrosio, U. (2009). Transdisciplinaridade. (2nd ed.). São Paulo.

Dilthey, W. (2010). Introdução às Ciências Humanas : Tentativa De Uma Fundamentação Para o Estudo Da Sociedade e Da História. Rio de Janeiro.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg. (2009). Verdade e Método II : Complementos e Índice. Petrópolis.

Lipovetsky, G. (2005). A Era Do Vazio : Ensaios Sobre O Individualismo Contemporâneo. Barueri.

Lowman, J. (2004). Dominando as Técnicas de Ensino. São Paulo.

Moraes, M. C. (1997). O paradigma Educacional Emergente. Campinas, SP.

Moraes, M. C. (2004). Pensamento Ecossistêmico : educação, aprendizagem e cidadania no século XXI. Petrópolis, RJ.

Moraes, M. C. (2008). Ecologia dos Saberes - Complexidade, Transdisciplinaridade e Educação. São Paulo.

Moraes, M. C. (2015). Transdisciplinaridade, Criatividade e Educação : Fundamentos Ontológicos E Epistemológicos. Campinas, SP.

Moraes, M. C. (2020). Pensamento Ecossistêmico: Educação, Aprendizagem e Cidadania. In : FEITOSA, Berenice et al. Educação Transdisciplinar: Escolas Criativas e Transformadoras.

Moraes, M. C., Batalloso Navas, J. M., & Mendes, P. C. (2014). Ética, Docência Transdisciplinar e Histórias de Vida : Relatos Em Reflexões Em Valores Eticos. Brasília.

Moraes, M. C., & Valente, J. A. (2008). Como Pesquisar Em Educação a Partir Da Complexidade E Da Transdisciplinaridade. São Paulo. https://doi.org/10.7213/rde.v7i22.4147

Morin, E. (2003). A Cabeça Bem-Feita : Repensar a Reforma, Reformar O Pensamento. (8nd ed.). Rio de Janeiro.

Morin, E., & Le Moigné, Jean-Louis. (2008). Inteligência da Complexidade : Epistemologia e Pragmática. Lisboa.

Nicolescu, B. (1996). La Transdisciplinarité : Manifeste. Monaco.

Ribeiro, D. (1997). Confissões. São Paulo.

Schleiermacher, F. D. E. (2010). Hermenêutica - Arte e Técnica da Interpretação. Petrópolis, RJ.

Torre, S., Pujol, M. A., & Moraes, M. C. (2008). Transdisciplinaridade e Ecoformação : Um Novo Olhar sobre a Educação. São Paulo.

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© Granthaalayah 2014-2022. All Rights Reserved.