Zaheer Ahmed Khan 1 ![]()

![]() ,

Uvesh Husain 1

,

Uvesh Husain 1![]()

![]()

1 Associate

Professor, Economics and Business Studies Department, Mazoon

College, Muscat, Sultanate of Oman

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

This study investigates the role of entrepreneurial marketing as a predictor of firm performance. The research integrates variables of the dynamic interaction: mediating role of diversity of network and learning capability, moderating role of competitive intensity on the relationship between entrepreneurial marketing and performance of the firm. The study is explanatory in nature. To ensure the accuracy of quantitative results based on the experience of study participants, we employed a mixed method of qualitative and quantitative data collection. Data was collected in two stages: 1) field survey, 2) interviews of SMEs owners in Oman. The sample was purposively drawn from SMEs managers perceived to be knowledgeable about the tourism industry. No significant relationship was found between entrepreneurial marketing and firm performance. In addition, it was found that network selection mediates the relationship between entrepreneurial marketing and firm performance; however, learning capability does not. This study

adds to the literature of the Omani market context on a strategic issue and

provides managers with useful insights. Mixed methods provide a

methodological contribution to understanding the dynamic relationship between

variables presented in the entrepreneurship literature. |

|||

|

Received 18 July 2022 Accepted 20 August 2022 Published 07 September 2022 Corresponding Author Uvesh Husain, owais.husain@mazcol.edu.om DOI 10.29121/granthaalayah.v10.i8.2022.4741 Funding: The research

leading to these results has received funding from the Research Council (TRC)

of the Sultanate of Oman under the Block Funding Program. TRC Block Funding

Agreement No: BFP/RGP/CBS/18/115”. Copyright: © 2022 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: SMEs, Entrepreneurial Marketing, Firm

Performance, Learning Capability, Diversity of Network Structure, Competitive

Intensity |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The concept of entrepreneurial marketing (EM) was introduced in 1982, and later extended by scholars Hills and Hultman (2011), Morris et al. (2002), Stokes (2000). Small firms are very limited in resources, so they must take marketing actions that are visionary and creative. Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are likely to be highly opportunity-oriented using resource leveraging for value creation as an important entrepreneurial marketing dimension Polas and Raju (2021). The EM paradigm integrates marketing and entrepreneurship into a comprehensive concept and characterizes EM through the following dimensions: proactiveness, opportunity focus, risk-taking, and innovativeness, customer intensity, resource leveraging, and value creation Hisrich and Ramadani (2017), Morris et al. (2002).

It is very important for the economic growth of a country to have a healthy SME sector. At the development stage of the Sultanate of Oman, the growth of small and medium enterprises (SMEs), to strengthen the economic growth of the country is highly emphasized in policies. In Oman, the government has been focusing on the role of SMEs in supporting tourism and implementing SME policies to meet the employment creation target through SME development. Sokhalingam et al. (2013). Marketing is the major determinant of business success, and SME entrepreneurs must master the marketing concept for their success and growth. The marketing practices of SME businesses differ from those of large organizations. This concern has attracted much attention from SME researchers who have found that traditional marketing practices are not suitable for SMEs; they must seek an entrepreneurial marketing approach. For SMEs to achieve sustainable growth and sustainability, they must utilize innovative marketing practices. It is important to understand that SMEs face specific challenges that prevent conventional marketing from being as effective as it could be Sadiku-Dushi et al. (2019). Therefore, adopting an entrepreneurial marketing philosophy is the most appropriate strategic decision for SMEs.

Therefore, Entrepreneurial Marketing (EM) considers the marketing limitations faced by SMEs and combines entrepreneurship with marketing. Growth and profitability are highly uncertain in a competitive, complex, and constantly evolving environment, and companies need to pursue new opportunities. Nowadays, companies face a wide range of risks that require them to develop contemporary business models. The entrepreneurial process is vital to helping companies recognize, explore, exploit opportunities, and strategize. Martin and Javalgi (2016), Yang and Gabrielsson (2017) .

Small businesses must develop an entrepreneurial culture to learn from experience, based on their knowledge of the market conditions. Creativity, openness to change, and self-efficacy is among the major factors influencing the entrepreneurial culture. Therefore, small, and medium-sized businesses are embracing entrepreneurial marketing Martin and Javalgi (2016). Researchers rarely address entrepreneurial marketing in relation to SMEs in Oman: the research has been concentrated on structural issues. For example, researchers Al Barwami et al. (2014), Al Buraiki and Khan (2018), Atef and Al-Balushi (2015), Bilal and Al Mqbali (2015), Saqib et al. (2017) have reported that policy and administrative challenges, lack of skills, and lack of production capacity followed by the financial and marketing issues hinder the growth of SMEs.

SMEs in Oman need to assess their marketing potential for knowledge creation, innovation, and skills development for sustainable growth Hussain (2017). The absence of adequate research on SMEs in the context of entrepreneurial marketing in Oman merits an empirical investigation to examine the impact of entrepreneurial marketing on the performance of SMEs. Therefore, given Oman's marketing landscape, this study examines the impact of entrepreneurial marketing (EM) on performance. Specifically, it considers the mediating effect of the network's learning capacity and diversity on the relationship between entrepreneurial marketing and SME performance. Furthermore, the study examines the impact of competitive intensity on the relationship between entrepreneurial marketing and SME performance.

2. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES

This research is grounded on Barney (1991) : concept of strategic resource-based view (SRBV) of firms. During recent years, there has been a great emphasis on a strategic resource-based view of the organization and dynamic capabilities Choi and Wacker (2011), Hitt et al. (2016). Capabilities, knowledge, learning, and resource dependence of organizations are among the resource-based view. SRBV theory leads towards competitive advantage and greater returns for resources and capabilities of a business and posts future strategies as the core management philosophy Sahoo (2019).

2.1. ENTREPRENEURIAL MARKETING AND FIRM PERFORMANCE

Due to increased market uncertainty, traditional marketing efforts have become ineffective in improving organizations' performance. Effective marketing can either directly or indirectly improve organizations' performance strategies through the entrepreneurial marketing approaches will help in enhancing SME's capabilities Eggers et al. (2012), Hakala (2011), Sahid and Hamid (2019). The concept of EM is diverse and there is a significant level of divergences in understanding it. Ioniţǎ (2012) clarified that differences between EM and small business marketing are driven by the differences between entrepreneurs and small business owners. Hills et al. (2010) argue about the difference between EM and traditional marketing due to entrepreneurial orientation (EO) and marketing orientation (MO) as constructs of EM. Mort, G et al. (2012) identified four key strategies for entrepreneurial marketing: 1) opportunity creation, 2) innovative products based on customer intimacy, 3) improved resources, 4) legitimacy. These core EM strategies are defined as a function of improved performance; therefore, the entrepreneurial marketing models a strategic decision-making process within the context of the market of SMEs. Effective strategies add value to entrepreneurial ventures and network and entrepreneurial marketing competencies are two key concepts to guide towards a strategic focus Kuratko et al. (2015).

Modern marketing entails currently successful tools such as traditional and digital marketing. Husain et al. (2021) revealed that digital marketing plays a vital role in the success of marketing: use of mobile apps significantly leads to higher brand engagement. Unlike traditional predictive logic (non-entrepreneurs’ approach), entrepreneurs think through an effective logic. Explaining entrepreneurial marketing Whalen et al. (2016) proposed that entrepreneurial marketing combines innovation, responsiveness and risk-taking to create, communicate and deliver value to customers, entrepreneurs, marketing specialists, their partners and society. He defined entrepreneurial marketing (EO) as “The process of opportunity discovery, opportunity exploitation and value creation are carried out by an individual who often exhibits a proactive orientation, innovation focus, and customer intensity and can leverage relationships and resources and manage risk” Haden et al. (2016). The customer is the central element of SMEs and customer orientation is a fundamental way of doing business among entrepreneurs.

A meta-analysis Kirca et al. (2005), Rauch et al. (2009) verified that marketing orientation (MO) and financial performance are positively correlated and both EO and MO have EM attributes (e.g., Risk Taking & Value Creation). Therefore, these commonalities anticipate a positive relationship between EM and the company's performance. Similarly, innovation and marketing capacity as dimensions of EM are driven by the fact that MO and EO respectively have a positive relationship to organizational performance. Hence, this study hypothesizes as following.

H1: Entrepreneurial marketing influences the

performance of SMEs.

2.2. LEARNING CAPABILITY

External marketing capability and human capital interact to achieve higher returns through market detection and knowledge creation. By leveraging the capabilities of outside-in marketing, firms can develop skill sets, as well as ensure employee engagement Mu et al. (2018). Learning capacity impacts the ability to innovate, to market efficiently, and to learn as well as it is linked to organizational learning and change Sahoo (2019). Dynamic capabilities have a significant effect on competitive advantage in a changing environment: higher dynamic capability and entrepreneurial marketing tends to be a highly competitive advantage Khouroh et al. (2020). Therefore, SMEs adjust their capabilities as part of a strategy to become competitive in the market. From a learning capacity perspective, knowledge is the content of a cognitive and social process embedded in an organization's work practices. Classifying learner organizations Antunes et al. (2020) suggest organizational learning as a process of creating organizational memory which corresponds to outputs. Consequently, organizing memory can be viewed as a result of organizational learning Migdadi (2019). Covin and Lumpkin (2011). explained organizations' learning capacity as a strategic perspective and resource that contributes to competitive advantage. The learning capabilities and entrepreneurial orientation are generally found to be positively related and strengthen each other’s effect on firm performance as a mediator Alegre and Chiva (2013), Altinay et al. (2016). Entrepreneurship orientation positively influences organizational learning levels Dada and Fogg (2016) . The company's market sensing capabilities are vital as an opportunity recognition capability for improving growth Miocevic and Morgan (2018). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis.

H2: The learning capability of the organizations

mediates the relationship between entrepreneurial marketing and the performance

of SMEs.

2.3. NETWORK STRUCTURE

Network structures provide ties and collaborations within and outsides of the organizational boundaries. Networks are a source of acquiring and sharing market knowledge for development. The network structure is more decentralized and less hierarchical, therefore, becomes more flexible and informal. Entrepreneurship research Hoang and Antoncic (2003), Hoang and Yi (2015), Slotte–Kock and Coviello (2010) emphasized that organizations use cohesion and trust-based social networks that affect the entrepreneurial strategic choice and outcomes. As a strategic posture, entrepreneurial orientation is one in which behaviour and actions are motivated by the search for opportunities. Shared resources from several clusters help in enhancing firm performance. Shared resources from several clusters contribute to firm performance. Hence, entrepreneurship-oriented firms follow entrepreneurial initiatives through existing and emerging networks as an open system mindset to enhance entrepreneurial posture Jiang et al. (2018). Capitalizing on emerging opportunities firms use networks for leveraging outside resources. The strength of an organization's resource base is enhanced by its internal and external networks. The diverse network structure exposes the firm to the identification of more marketing opportunities in their environment. The diversity of networks enables entrepreneurs with a varying set of knowledge and resources that reinforce value creation and proactive behaviour Nieves and Osorio (2015), Nsereko et al. (2018). Therefore, a diverse portfolio of alliances with partners leads to the enhancement of innovative capability and legitimacy in the marketplace through inclusive attention to various stakeholders. Furthermore, strong ties help companies cut transaction costs and build trust with customers. Thus, we present our hypothesis.

H3: Network structure mediates the relationship between

entrepreneurial marketing and the performance of SMEs.

2.4. COMPETITIVE INTENSITY

Morrish et al. (2010)explained that competition urges the firms to be more flexible to succeed, which is one of the important aspects of EM. The competitive intensity forces the firms to be more aggressive to discover new aspects to satisfy customer needs Kohli and Jaworski (1990). As a result of a competitive environment, firms are willing to take diverse risks in the pursuit of opportunities. Competitive actions are less important to firms than exploring opportunities actively. Service standardization, new product development, and technology advancement are the main innovations due to competitive intensity Njoroge et al. (2020). The competitive hostility reinforces the relationship of EO, marketing capabilities, and venture performance Therefore, the moderating influence of competitive intensity is obvious to hold for the EM-performance relationship. Due to the intense competition in the industry, and to the turbulence in the environment, EO-MO implementation provides an opportunity to align with EO and to hedge risks by remaining close to customers Morgan and Anokhin (2020). The intensity of competition enhances the firm's propensity of engagement in EO Whalen et al. (2016) and the relationship of marketing capabilities, entrepreneurial orientation, and firm performance rely on competitive intensity Martin and Javalgi (2016). Considering this, we propose the following hypothesis.

H4: Competitive intensity moderates the relationship

between entrepreneurial marketing and the performance of SMEs.

3. METHODOLOGY

This research used a mixed-method approach combining semi structured interviews and a structured questionnaire. Combining mixed method with quantitative data served as an effective way to understand the voice of the participants and to ensure the outcome of quantitative results based on the experiences of the participants.

Data was collected in two stages: 1) survey data collection; 2) interviews. Purposive sampling was used to select firms representing tourism industry and owners, managers, and senior employees of SMEs from the tourism sector was selected in the sample. Out of 400 questionnaires distributed via email and 142 via personal contact, 127 usable questionnaires were received and used for analysis Table 1.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Respondents' Profile |

|||

|

Type of

Business |

Field

Survey |

Participants In Interview |

|

|

SME |

Respondents |

||

|

Tourism services |

8 |

14 |

2 |

|

Travel Trade |

10 |

18 |

2 |

|

Accommodation |

22 |

39 |

2 |

|

Foods and Beverages |

10 |

20 |

1 |

|

Attractions and retail trade |

13 |

25 |

1 |

|

Car rental services |

7 |

11 |

1 |

|

Total |

70 |

127 |

09 |

|

Small firms |

54 |

||

|

Medium firms |

16 |

||

|

Source: Field survey |

|||

For quantitative data, a self-administered structured questionnaire measuring responses on a seven-point Likert scale was used based on adapted survey items from previous studies. To measurement entrepreneurial marketing, items were adapted from Fiore et al. (2013), diversity of the network Zahra et al. (2000), learning capability Day (1994), competitive intensity measures Kohli (1993).

Based on the objectivity of the topic and methodology Creswell (2013), purposive sampling was used, and 09 business managers/owners were selected considered as key informant to provide real information based on their experience and knowledge. Proceeding into investigations through qualitative data, 7 semi-structured, open-ended interview questions derived from constructing items of quantitative survey were used. Questions were available in both English and Arabic languages. Interviews from individual participants were conducted face-to-face and through online video discussion moderated by researchers. The interview data were analysed based on a three-stage procedure Creswell et al. (2007), Miles and Huberman (1984) : transcribing, reduced data into themes through coding, and representing the data.

Table 2

|

Table 2 |

|

|

Suggested steps |

Analytical steps |

|

Familiarizing with data |

· Verbatim transcription in Arabic and English languages with systematic and equal transcription of all the interviews. · Translation of Arabic language interviews in English. · Reading of transcripts several times and recording codes separately. Listening audio and video recordings of the interviews of respondents several times to assure accuracy in translation and transcription. |

|

Searching for themes |

· The moderator and co-moderators discussed the different pre-codes after every interview. Themes from patterns were identified with a focus on data from actual verbal statements not the goals of the study. |

|

Review of themes |

· Deriving themes from codes. Examination of differences between the interviews. Discussion on themes and sub-theme regarding their relevance with the goals of the research. |

|

Definitions and names of themes. |

· Interviews were listened to again to assure the themes and their names. |

|

Reporting |

· Discussion between authors about how to describe and report them in an article. |

4. QUANTITATIVE DATA ANALYSIS

Several formatively measured constructs are included in the model to better understand the complex phenomenon through theoretical extensions. There are issues regarding distribution, and there is uncertainty about the normality of the data. A theoretical framework can be tested from a prediction perspective using PLS-SEM in such conditions. Hair Jr et al. (2016). The analysis was carried out at three levels: evaluation of the measurement model, structural model, and predictive relevance of the model.

4.1. EVALUATION OF THE MEASUREMENT MODEL

For reflective model, internal consistency, convergent validity, and discriminant validity Hair et al. (2020) assessed the measurement model. Table 3 shows the key indicators; the average variance extracted (AVE), and item loading (loadings > 0.708, AVE > 0.5) confirmed the convergent validity Hair et al. (2013). Internal consistency and reliability were suggested by Composite reliability (CR), Cronbach’s alpha (C>0.70), and ρA above 0.70 Henseler et al. (2015).

Table 3

|

Table 3 Construct Validity |

||||||

|

Construct |

Item |

Outer loading |

Cronbach’s alpha |

rho_A |

CR |

AVE |

|

Competitive Intensity (CI) |

ci1 |

0.871 |

0.813 |

0.898 |

0836 |

0.787 |

|

ci2 |

0.866 |

|||||

|

ci3 |

0.882 |

|||||

|

ci4 |

0.928 |

|||||

|

Entrepreneurial Marketing (EM) |

em1 |

0.735 |

0.800 |

0.834 |

0.866 |

0.618 |

|

em2 |

0.864 |

|||||

|

em3 |

0.744 |

|||||

|

em4 |

0.795 |

|||||

|

|

em5 |

0.809 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

em6 |

0.727 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

em7 |

0.723 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

em8 |

0.754 |

|

|

|

|

|

Firm Performance (FP) |

fp1 |

0.894 |

0.751 |

0.771 |

0.858 |

0.670 |

|

fp2 |

0.820 |

|||||

|

fp3 |

0.734 |

|||||

|

Learning Capability (LC) |

lc1 |

0.882 |

0.815 |

0.822 |

0.879 |

0.645 |

|

lc2 |

0.800 |

|||||

|

lc3 |

0.796 |

|||||

|

lc4 |

0.727 |

|||||

|

Diversity of Networking (NW) |

nw1 |

0.907 |

0.790 |

0.839 |

0.876 |

0.703 |

|

nw2 |

0.777 |

|||||

|

nw3 |

0.827 |

|||||

|

|

nw4 |

0.783 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

nw5 |

0.813 |

|

|

|

|

The heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) measure Hair et al. (2019), Henseler et al. (2015) determined the discriminant validity; and all the HTMT values Table 4 are lower than 0.90 indicated discriminant validity Hair et al. (2019).

Table 4

|

Table 4 Discriminant Validity: HTMT |

||||

|

CI |

EM |

FP |

LC |

|

|

CI |

||||

|

EM |

0.081 |

|||

|

FP |

0.168 |

0.667 |

||

|

LC |

0.179 |

0.856 |

0.729 |

|

|

NW |

0.185 |

0.719 |

0.838 |

0.818 |

4.2. STRUCTURAL MODEL

To assess the structural model (relationships between the latent variables) we investigated the structural model's significance, relevance, predictive power, and effect size to evaluate its significance and relevance. Bootstrapping (5000 samples) was used to test the significance of the relationship between constructs of the structural model Preacher and Hayes (2008).

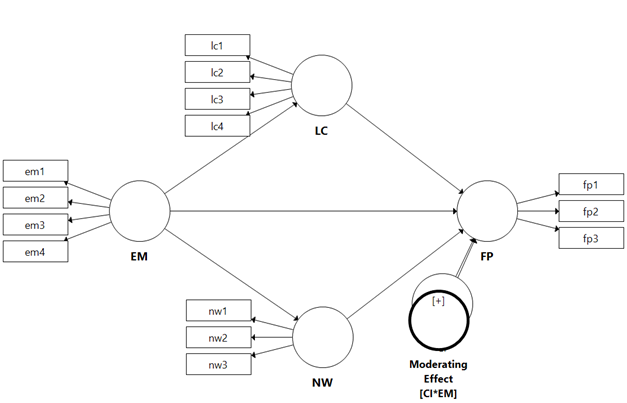

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Conceptual Model |

4.3. ANALYSIS OF HYPOTHESIZED RELATIONS

Hypothesized direct relations Table 5 shows an insignificant effect of entrepreneurial marketing on firm performance (H1: β= 0.166, t = 0.966, p >0.05). Hence, H1 was not supported. Other hypothesized direct relationship: EM -> LC (β = 0.725, t = 14.196, p<0.05), EM -> NW (β = 0.631, t = 9.977, p<0.05), NW -> FP (β = 0.471, t = 3.358, p<0.05) were positive and significant. The relationship LC -> FP (β = 0.110, t = 0.577, p> 0.05) was positive but insignificant.

Table 5

|

Table 5 Analysis of Path Co-Efficient |

||||||

|

Hypothesis |

Path |

St. Beta |

SE |

T-Statistics |

P-Values |

95% Because |

|

H1 |

EM -> FP |

0.166 |

0.146 |

0.966 |

0.334 |

[-0.165, 0.399] |

|

EM -> LC |

0.725 |

0.051 |

14.196 |

0.000 |

[0.595,0.803] |

|

|

EM -> NW |

0.631 |

0.062 |

9.977 |

0.000 |

[0.476,0.732] |

|

|

LC -> FP |

0.110 |

0.186 |

0.577 |

0.564 |

[-0.272,0.454] |

|

|

NW -> FP |

0.471 |

0.146 |

3.358 |

0.001 |

[0.176,0.740] |

|

|

Dependent variable: Firm

Performance (FP), Predictors: Entrepreneurial

Marketing (EM) FP=Firm Performance, NW=Networking, LC= Learning Capability |

||||||

4.4. ANALYSIS OF INDIRECT RELATIONS

Table 6 shows the indirect effects. The indirect effect (EM -> LC -> FP: β=0.079, t= 0.570, p>0.05), [LL=-0.202, UL=0.333] does not indicate a mediation. Hence, H2 was not supported. Therefore, the learning capability of firms does not mediate the relationship between EM and FP. The effect of network structure (EM -> NW -> FP: β=0.294, t= 3.395, p< 0.05), [LL = 0.124, UL = 0.473] indicated a mediation. The direct relationship (EM>NW and NW>FP) is significant and indicates an indirect-only (full) mediation (Zhao, Lynch Jr, and Chen 2010) and supports H3. Competitive Intensity ([CI*EM] -> FP: β=0.143, t= 1.164, p>0.05) and [LL=-0.536, UL=0.119] did not indicate moderation.

Table 6

|

Table 6 Analysis of Indirect Effects |

||||||

|

Hypothesis |

Path |

St. Beta |

SE |

T-Statistics |

P-Values |

95% Because |

|

Mediating effects |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

H2 |

EM -> LC -> FP |

0.079 |

0.136 |

0.570 |

0.569 |

[-0.202,0.333] |

|

H3 |

EM -> NW -> FP |

0.294 |

0.09 |

3.395 |

0.001 |

[0.124,0.473] |

|

Moderating Effect |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

H4 |

[CI*EM] -> FP |

0.143 |

0.182 |

1.164 |

0.245 |

[-0.536,0.119] |

|

Dependent variable: Firm

Performance (FP), Predictor: Entrepreneurial Marketing (EM) Moderator: Competitive

Intensity (CI) Mediators: Diversity of

Networks (NW), Learning Capability (LC) |

||||||

Predictive Quality

For predictive relevance, the model and its parameter estimates were tested using blindfolding (Q2) to assess how well-observed values were constructed in model based on a prognosis of original values. Q2 greater than zero has predictive relevance Table 7. R2 values indicated a moderate variance explained (i.e., FP= 48.9 %, LC= 51.7 % and NW=38.9%) by endogenous latent constructs. Q² _predict values for constructs are above 0 which indicated a predictive relevance Henseler et al. (2015), Sarstedt et al. (2017).

Table 7

|

Table 7 Model Analysis |

||||

|

Endogenous latent constructs |

R2 |

R2 Adjusted |

Q² |

Q² _predict |

|

FP |

0.489 |

0.460 |

0.278 |

0.238 |

|

LC |

0.517 |

0.511 |

0.318 |

0.325 |

|

NW |

0.389 |

0.38 |

0.259 |

0.457 |

|

Q2:

Cross-validated constructs redundancy, Q² _predict predictive relevance, R2:

Coefficient of determination Notes: Q2

> =0 small, 0.25 medium and 0.5 large Hair et al. (2019) |

||||

VIF values for constructs and effect size (f2) measured multicollinearity and the strength of the relationship between variables Table 8. VIF values fall within the acceptable range (i.e., above 2); hence, there is no indication of collinearity issue Hair et al. (2019). The significance of the effect size (f2) was determined based Cohen (1988) criterion.

Table 8

|

Table 8 Effect Size |

||

|

Relationship |

VIF |

f2 |

|

NW>FP |

1.973 |

0.034 |

|

EM>FP |

2.312 |

0.021 |

|

LC>FP |

2.526 |

0.205 |

|

EM->LC |

1.000 |

0.272 |

|

EM>NW |

1.000 |

0.636 |

|

VIF:

Variance inflation factor, f2: effect size Notes:

f2> 0.02 small, 0.15 medium, and 0.35 large Cohen (1988) |

||

Predictive relevance

PLS-SEM Table 9 exhibits the predictive relevance for constructs. The Q2predict values are above zero and all the indicators RMSE (PLS -SEM) are less than RMSE (LM), which indicate high predictive power of the model Shmueli et al. (2019).

Table 9

|

Table 9 PLS Predict Assessment of Manifest Variables |

||||

|

PLS-SEM |

LM |

PLS_SEM |

||

|

RMSE |

Q²_predict |

RMSE |

-LM (RMSE) |

|

|

fp1 |

1.418 |

0.171 |

1.641 |

-0.223 |

|

fp2 |

1.377 |

0.174 |

1.863 |

-0.486 |

|

fp3 |

1.407 |

0.312 |

1.652 |

-0.245 |

|

lc1 |

1.252 |

0.451 |

1.750 |

-0.498 |

|

lc2 |

1.600 |

0.295 |

2.004 |

-0.404 |

|

lc3 |

1.561 |

0.229 |

2.603 |

-1.042 |

|

lc4 |

1.452 |

0.296 |

1.875 |

-0.423 |

|

nw1 |

1.160 |

0.361 |

1.620 |

-0.460 |

|

nw2 |

1.249 |

0.134 |

1.969 |

-0.720 |

|

nw3 |

1.132 |

0.241 |

1.457 |

-0.325 |

4.5. QUALITATIVE DATA ANALYSIS

The thematic analysis of qualitative data Table 10 through transcribed text aimed at reflecting the participant’s voice and conditions Polit and Beck (2012) to get the real picture of the phenomenon under investigation. Researchers used analytic steps Braun and Clarke (2006), Clarke and Braun (2014) to report the outcomes of interviews using inductive codes and derived themes as follows.

Table 10

|

Table 10 Analysis of Interview Information |

|||

|

Category |

Codes |

Theme |

Descriptors |

|

Diversity of network structure |

· External linkage · Networking behaviour · Clustering ·

Social

capital ·

Facilitation |

Benefits from collaboration |

Market relationship is very important and triggers and motivates us to internationalize, influence our market selection decision and mode-of-entry decision. Network structure allows access to additional relationships, helpful to gain initial credibility, and channels in the market. |

|

Learning capability |

· Information sharing · Opportunity recognition · Enhance capabilities |

Dynamic capabilities to sense the market |

Learning capability helps in incorporating knowledge acquired through firms' engagement in marketing. None of the respondents explained meaningfully, that what is their strategy to enhance learning capability. |

|

Entrepreneurial marketing |

· Proactive · Cost-effective · Innovation · Customer focus · Value · Advertisement |

Seek new business opportunities

|

The highest emphasis was on customer satisfaction followed by customer relationship. Value creation was recognized for successful marketing. Risk-taking and resource leverage remained missing from participants’ conceptualization. |

|

Firm Performance |

· Profit · New customers · New markets |

Growth |

Participants recognized the role of marketing actions related to the performance of the firm. There was no specific emphasis on which of the actions has supported performance in which areas of growth. Mostly, participants discuss on the general contribution of marketing to firm performance. |

|

Source: Interview data |

|||

Regarding the diversity network structure, 7 respondents (interviewed) acknowledged that they benefited from the network structure. The rest of the interviewees argued on the importance of the network structure but did not acknowledge gain from the diversity of the network structure to impact on their marketing for better performance of the firm.

“I agree that networking is very important. We need to establish networks in the market to get leads. Right now, I cannot refer to any network that has benefited my business directly, but network is a good source of information for me. As part of industry, we believe that business networking with different types of firms related to tourism business is very important”. (participant)

The overall theme of discussion conveyed that firms are benefiting from networking across different segments of market and marketing endeavor has a positive relationship with the diversity of network and eventually along with entrepreneurial marketing network contributes to the performance of the firm.

Participants provided useful insights in highlighting the importance of learning capabilities. Only four respondents agreed with their success in developing their learning marketing strategies.

“I agree that learning capability is critical to the creation of successful business strategies. Customers' feedback and industry contacts help us learn on a day-to-day basis. There are no specific learning targets or methods, but overall experience and information are extremely valuable in helping us to understand new market trends. It is hard to see how learning has benefited my business recently”. (participant).

The rest of the respondents did not report any benefits to their marketing gained from learning. This was not evident in interviews that how firms are developing and utilizing knowledge generated through learning. Thus, based on lack of systematic knowledge creation, we conclude that learning capability does not have any positive impacts on their performance.

Interviewees reasonably acknowledged the differences between entrepreneurial marketing and conventional marketing. All interviewed managers emphasized that customer satisfaction was the most important factor, followed by value creation and relationship with customers. All the interviewees emphasized the increasing value for customers specifically through new products and set of benefits attributed to product. The participants recognized the importance of new marketing methods; however, no one explicitly confirmed or explained how their firm was benefiting from entrepreneurial marketing. Interviewees did not highlight risk-taking and resource leverage during the discussion. Hence, a complete orientation of entrepreneurial marketing is lacking among firms. The participants acknowledged firm performance in terms of sales, profits, customers, and new markets, but they did not explicitly identify which actions contributed to growth in which areas.

5. DISCUSSION

5.1. THEORETICAL IMPLICATIONS

The study significantly describes on the strategic orientation of firms through their marketing approach. The study justified the gap successfully through incorporation of diversity of networks and learning capability with entrepreneurial marketing and firm performance. The outcomes provide a valuable contribution to marketing and entrepreneurship literature related to Omani context. A valuable contribution to understanding the entrepreneurial landscape of Oman is made by the research as a contribution to entrepreneurial learning. Furthermore, it provides valuable information on Omani SMEs' marketing practices.

5.2. PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

The research has an economic impact for Omani entrepreneurs in the exploration of marketing efforts for the success of their business. The outcomes of the research provide a practical insight to Omani SMEs to define marketing opportunities problems to generate, refine and evaluate marketing actions for the success of their business. The improvement in the performance of SMEs will foster an entrepreneurial culture and promote the creation of self-employment because growth in SMEs will help to reduce unemployment. Also, help the Omani institutions such as Authority for Small and Medium Enterprises Development (Riyada), Oman’s SME Development Fund (SMEF), Al Raffd Fund, Khazzan Project, the industrial innovation support programs, banks, and other institutions supporting SMEs and new ventures in developing marketing orientation programs for SMEs and entrepreneurs.

5.3. FUTURE DIRECTIONS AND LIMITATIONS

Potential limitations of the study cannot be ignored before generalizing the results of the study. First, unavoidable circumstances of COVID-19, kept researchers very limited in accessing the firms. Second, sampling in interviews was purposive due to accessibility issues and size in field survey is not large enough to represent the population adequately. Third, some other intervening variables and factors evident in the literature were not considered in the current study. However, despite the limitations, the outcomes of the study have successfully explained the phenomenon under investigation and achieved its objectives. Future research may include some other variables and contextual factors such as type of ownership of firm, age of firm, and owners’ experience to gain more clarity in understanding the phenomenon under investigation.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Al Kalbani, K. A., Rahman, A. A., and Malaysia-Talal, A. L. (2018). Implementing 3d Spatial Data Infrastructure for Oman-Issues and Challenges.

Al Barwami, K. M., Al-Jahwari, M. R., Al-Saidi, A. S., and Al Mahrouqi, F. S. (2014). Towards a Growing, Competitive and Dynamic Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Sector in Oman : Strategy And Policies, Central Bank of Oman, Economic Research and Statistics Department.

Al Buraiki, A., Khan, F. R. (2018). Finance and Technology: Key Challenges Faced By Small and Medium Enterprises (Smes) in Oman, International Journal of Management, Innovation and Entrepreneurial Research EISSN, 2395–7662. https://doi.org/10.18510/ijmier.2018.421

Alegre, J., Chiva, R. (2013). Linking Entrepreneurial Orientation and Firm Performance: The Role of Organizational Learning Capability and Innovation Performance. Journal of Small Business Management, 51(4), 491–507. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12005

Altinay, L., Madanoglu, M., De Vita, G., Arasli, H., and Ekinci, Y. (2016). The Interface Between Organizational Learning Capability, Entrepreneurial Orientation, And SME Growth. Journal of Small Business Management, 54(3), 871–891. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12219

Antunes, H. De J. G., and Pinheiro, P. G. (2020). Linking Knowledge Management, Organizational Learning and Memory, Journal of Innovation and Knowledge, 5(2), 140–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2019.04.002

Atef, T. M., Al-Balushi, M. (2015). Entrepreneurship as a Means for Restructuring Employment Patterns. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 15(2), 73–90. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1467358414558082

Barney, J. (1991). Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage, Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F014920639101700108

Bilal, Z. O., Al Mqbali, N. S. (2015). Challenges and Constrains Faced by Small and Medium Enterprises (Smes) in Al Batinah Governorate of Oman. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development. https://doi.org/10.1108/WJEMSD-05-2014-0012

Braun, V., Clarke, V. (2006). Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology, Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Choi, T., Wacker, J. G. (2011). Theory Building in the Om. Scm Field: Pointing to the Future by Looking at the Past, 47(2), 8-11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2011.03219.x

Clarke, V., Braun, V. (2014). Thematic Analysis, in Encyclopedia of Critical Psychology, Springer, 1947–1952.

Cohen, J. (1988). The Effect Size, Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 77–83.

Covin, J. G., Lumpkin, G. T. (2011). Entrepreneurial Orientation Theory and Research: Reflections on a Needed Construct, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(5), 855–872. https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1540-6520.2011.00482.x

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Steps in Conducting a Scholarly Mixed Methods Study, 1-54.

Creswell, J. W., Hanson, W. E., Clark Plano, V. L., and Morales, A. (2007). Qualitative Research Designs: Selection and Implementation, The Counseling Psychologist, 35(2), 236–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006287390

Dada, O., Fogg, H. (2016). Organizational Learning, Entrepreneurial Orientation, and The Role of University Engagement in Smes, International Small Business Journal, 34(1), 86–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242614542852

Day, G. S. (1994). The Capabilities of Market-Driven Organizations. Journal of Marketing, 58(4), 37–52.

Eggers, F., Hansen, D. J., And Davis, A. E. (2012). Examining the Relationship Between Customer and Entrepreneurial Orientation on Nascent Firms’ Marketing Strategy, International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 8(2), 203–222.

Fiore, A. M., Niehm,

L. S., Hurst, J. L., Son, J., and Sadachar, A. (2013).

Entrepreneurial Marketing : Scale Validation with Small, Independently-Owned

Businesses, Journal of Marketing Development and Competitiveness, 7(4), 63.

Haden, S. S. P., Kernek, C. R., and Toombs, L. A. (2016). The Entrepreneurial Marketing of Trumpet Records. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, 18(1), 109-126. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRME-04-2015-0026

Hair Jr, J. F., Howard, M. C., and Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing Measurement Model Quality in PLS-SEM Using Confirmatory Composite Analysis, Journal of Business Research, 109, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.069

Hair Jr, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Matthews, L. M., and Ringle, C. M. (2016). Identifying and Treating Unobserved Heterogeneity with FIMIX-PLS: Part I–Method. European Business Review, 28(1), 63-76. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-09-2015-0094

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2013). Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling : Rigorous Applications, Better Results and Higher Acceptance, Long Range Planning, 46(1–2), 1–12.

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., and Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM, European Business Review, 31(1), 2-24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Hakala, H. (2011). Strategic Orientations in Management Literature: Three Approaches to Understanding the Interaction Between Market, Technology, Entrepreneurial and Learning Orientations. International Journal of Management Reviews, 13(2), 199–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2010.00292.x

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2015). A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135.

Hills, G. E., Hultman, C. M., Kraus, S., and Schulte, R. (2010). History, Theory and Evidence of Entrepreneurial Marketing–An Overview, International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 11(1), 3–18. https://dx.doi.org/10.1504/IJEIM.2010.029765

Hills, G. E., And Hultman, C. M. (2011). Academic Roots : The Past And Present of Entrepreneurial Marketing, Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship, 24(1), 1–10.

Hisrich, R. D., Ramadani, V. (2017). Effective Entrepreneurial Management, Effective Entrepreneurial Management.

Hitt, M. A., Xu, K., and Carnes, C. M. (2016). Resource Based Theory in Operations Management Research. Journal of Operations Management, 41, 77–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2015.11.002

Hoang, H., Antoncic, B. (2003). Network-Based Research in Entrepreneurship: A Critical Review. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(2), 165–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00081-2

Hoang, H., Yi, A. (2015). Network-based research in entrepreneurship: A decade in review, 11(1), 1-54. http://dx.doi.org/10.1561/0300000052

Husain, U., Javed, S., and Ananda, S. (2021). Digital Marketing as a Game Changer Strategy to Enhance Brand Performance, International Journal of Technology Marketing, 15(2-3), 107-125. https://dx.doi.org/10.1504/IJTMKT.2021.10041546

Hussain, E. (2017). Exploration of Entrepreneurial Marketting Orientation Model Among Smes in Oman, International Journal of Economics and Management Sciences, 6(3), 1-6.

Ioniţǎ, D. (2012). Entrepreneurial Marketing : A New Approach for Challenging Times. Management and Marketing, 7(1).

Jiang, X., Liu, H., Fey, C., and Jiang, F. (2018). Entrepreneurial Orientation, Network Resource Acquisition, and Firm Performance: A Network Approach, Journal of Business Research, 87, 46–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.02.021

Khouroh, U., Sudiro, A., Rahayu, M., and Indrawati, N. (2020). The Mediating Effect of Entrepreneurial Marketing in the Relationship Between Environmental Turbulence and Dynamic Capability with Sustainable Competitive Advantage: An Empirical Study in Indonesian Msmes. Management Science Letters, 10(3), 709–720. http://dx.doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2019.9.007

Kirca, A. H., Jayachandran, S., and Bearden, W. O. (2005). Market Orientation : A Meta-Analytic Review and Assessment of its Antecedents and Impact on Performance. Journal of Marketing, 69(2), 24–41.

Kohli, A. K., Jaworski, B. J., and Kumar, A. (1993). MARKOR: A Measure of Market Orientation, Journal of Marketing Research, 30(4), 467–477. https://doi.org/10.2307/3172691

Kohli, A. K., and Jaworski, B. J. (1990). Market Orientation: The Construct, Research Propositions, and Managerial Implications. Journal of Marketing, 54(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251866

Kuratko, D. F., Morris, M. H., and Schindehutte, M. (2015). Understanding the Dynamics of Entrepreneurship Through Framework Approaches. Small Business Economics, 45(1), 1–13.

Martin, S. L., Javalgi, R. R. G. (2016). Entrepreneurial Orientation, Marketing Capabilities and Performance: The Moderating Role of Competitive Intensitjy on Latin American International New Ventures, Journal of Business Research, 69(6), 2040–2051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.10.149

Migdadi, M. M. (2019). Organizational Learning Capability, Innovation and Organizational Performance. European Journal of Innovation Management, 24(1), 151-172. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-11-2018-0246

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M. (1984). Drawing Valid Meaning from Qualitative Data: Toward a Shared Craft. Educational Researcher, 13(5), 20–30. https://doi.org/10.2307/1174243

Miocevic, D., Morgan, R. E. (2018). Operational Capabilities and Entrepreneurial Opportunities in Emerging Market Firms, International Marketing Review, 35(2), 320-341. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-12-2015-0270

Morgan, T., Anokhin, S. A. (2020). The Joint Impact of Entrepreneurial Orientation and Market Orientation in New Product Development: Studying Firm and Environmental Contingencies. Journal of Business Research, 113, 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.06.019

Morris, M. H., Schindehutte, M., and Laforge, R. W. (2002). Entrepreneurial Marketing: A Construct for Integrating Emerging Entrepreneurship and Marketing Perspectives, Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 10(4), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.2002.11501922

Morrish, S. C., Miles, M. P., and Deacon, J. H. (2010). Entrepreneurial Marketing: Acknowledging the Entrepreneur and Customer-Centric Interrelationship, Journal of Strategic Marketing, 18(4), 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/09652541003768087

Mort, G. S., Weerawardena, J., and Liesch, P. (2012). Advancing Entrepreneurial Marketing. European Journal of Marketing, 46(3/4), 542-651. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561211202602

Mu, J., Bao, Y., Sekhon, T., Qi, J., and Love, E. (2018). Outside-In Marketing Capability and Firm Performance. Industrial Marketing Management, 75, 37–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2018.03.010

Nieves, J., Osorio, J. (2015). The Role of Social Networks in Knowledge Creation, in the Essentials of Knowledge Management Springer, 333–364.

Njoroge, M., Anderson, W., Mossberg, L., and Mbura, O. (2020). Entrepreneurial Orientation in the Hospitality Industry: Evidence from Tanzania, Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 12(4), 523-543. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-11-2018-0122

Nsereko, I., Balunywa, W., Munene, J., Orobia, L., and Muhammed, N. (2018). Personal Initiative: Its Power in Social Entrepreneurial Venture Creation, Cogent Business and Management, 5(1), 329-349. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2018.1443686

Polas, M. R. H., Raju, V. (2021). Technology and Entrepreneurial Marketing Decisions During COVID-19, Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 22(2), 95–112.

Preacher, K. J., Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic And Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models, Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891.

Rauch, A., Wiklund, J., Lumpkin, G. T., and Frese, M. (2009). Entrepreneurial Orientation and Business Performance: An Assessment of Past Research and Suggestions for the Future, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 761–787. https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1540-6520.2009.00308.x

Sahid, S., Hamid, S. A. (2019). How to Strategize Smes Capabilities Via Entrepreneurial Marketing Approaches, Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 23(1), 1–5.

Sahoo, S. (2019). Quality Management, Innovation Capability and Firm Performance. The TQM Journal, 31(6), 1003-1027. https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-04-2019-0092

Saqib, M., Baluch, N. H., And Udin, Z. M. (2017). Moderating Role of Technology Orientation on the Relationship Between Knowledge Management and Smes’ Performance In Oman : A Conceptual Study, International Journal of Economic Perspectives, 11(1).

Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., and Hair, J. F. (2017). Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. Handbook of Market Research, 26, 1–40.

Shmueli, G., Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Cheah, J.-H., Ting, H., Vaithilingam, S., and Ringle, C. M. (2019). Predictive Model Assessment In PLS-SEM: Guidelines for Using Plspredict, European Journal of Marketing, 53(11), 2377-1347. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-02-2019-0189

Slotte–Kock, S., Coviello, N. (2010). Entrepreneurship Research on Network Processes: A Review and Ways Forward, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(1), 31–57. https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1540-6520.2009.00311.x

Stokes, D. (2000). Putting Entrepreneurship Into Marketing: The Processes of Entrepreneurial Marketing, Journal of Research in Marketing And Entrepreneurship, 2(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1108/14715200080001536

Whalen, P., Uslay, C., Pascal, V. J., Omura, G., Mcauley, A., Kasouf, C. J., Jones, R., Hultman, C. M., Hills, G. E., And Hansen, D. J. (2016). Anatomy of Competitive Advantage: Towards a Contingency Theory Of Entrepreneurial Marketing, Journal of Strategic Marketing, 24(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2015.1035036

Yang, M., Gabrielsson, P. (2017). Entrepreneurial Marketing of International High-Tech Business-To-Business New Ventures: A Decision-Making Process Perspective, Industrial Marketing Management, 64, 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2017.01.007

Zahra, S. A., Ireland, R. D., and Hitt, M. A. (2000). International Expansion by New Venture Firms: International Diversity, Mode of Market Entry, Technological Learning, and Performance, Academy of Management Journal, 43(5), 925–950. https://doi.org/10.2307/1556420

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© Granthaalayah 2014-2022. All Rights Reserved.