|

|

|

|

Inter-State Disparities in Healthcare Costs, Health Insurance Coverage and Financial Protection in India: A Comparative Analysis of National Sample Surveys for 1986-87, 1995-96, 2004 and 2014

Anil Gumber 1![]()

![]() ,

N. Lalitha 2

,

N. Lalitha 2![]()

![]() , Biplab Dhak 3

, Biplab Dhak 3![]()

![]()

1 Senior

Health Economist at Faculty of Health and Wellbeing, Sheffield Hallam

University, Sheffield, UK

2 Retired

from a Professorial position at Gujarat

Institute of Development Research, Ahmedabad, India

3 Assistant Professor, A N Sinha Institute of Social Studies, Patna, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

By

analysing data from the National Sample Survey for

four rounds (1986–87, 1995–96, 2004 and 2014) this research focuses on

changes in people's health seeking behaviour, the

cost of treatment, and principal factors affecting health insurance premium

payments by BPL and APL families. With variations between states, it is

discovered that over time, less people sought care from public providers and

more people preferred private providers. Despite the fact

that both men and women are now more likely to seek treatment for

their illnesses, a sizeable portion of the population (more in rural than in

urban areas), still refuses treatment because they believe their illness is

not serious enough to warrant it. Whilst the cost of healthcare has gone up

over time, the difference between public and private costs of treatment has

shrunk, possibly as a result of the higher recurring

cost in public health facilities and imposing of user fees and cutting on the

delivery of free medication. Since the middle of the 2000s, public insurance

companies have offered low-cost hospitalisation

insurance programmes like the Jan Arogya Bima

Policy and Rashtriya Swasthya

Bima Yojana (RSYB) to help with the healthcare needs of the underprivileged

sector of society. According to the insurance premiums, more households that

paid premiums in 2004 and 2014 belonged to groups with higher Monthly Per

Capita Expenditures (MPCE) and were not economically in the poorest tier. The

inter-quintile MPCE differential (between the top and bottom quintile) also

reveals significant inter-state disparities in terms of the percentage of

households that paid a premium and the percentage of households that had

health insurance. The factors that determine whether a family enrols in health insurance imply that increasing

enrolment from the poor households got coverage through RSBY. At the national

level, BPL/APL households with insurance reported, on average, higher hospitalisation costs than non-insured households, with

the difference being significantly higher for urban households. This finding

suggests the prevalence of insurance collusion and moral hazard, particularly

in the cities from developed states of Punjab, Haryana, Gujarat, and Maharashtra.

Further, BPL households, particularly from rural India, have received very

little financial relief as a result of the

insurance. |

|||

|

Received 27 March 2023 Accepted 28 April 2023 Published 13 May 2023 Corresponding Author Anil Gumber, A.Gumber@shu.ac.uk DOI 10.29121/ijetmr.v10.i5.2023.1315 Funding: This research received

no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or

not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2023 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Health

Insurance Coverage, Financial Protection, Healthcare Costs |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Healthcare

system in India is a typical mix of public and private providers with wide

inter-state disparities in terms of their spread and coverage. The total health

expenditure (THE) for India is estimated to be 3.16% of Gross Domestic Product

(GDP) of which public sector contributed 40.61%, household out-of-pocket (OOP)

48.21%, the Private Health Insurance 6.57% and the remainder by Social Security

and External Donors (National Health Accounts 2018-19, Government of India. (2022). Since the inception of National

Health Accounts, the total health expenditure as percentage of GDP has

continuously declined from 4.2% in 2004-05 to 3.8% in 2015-16 and further to

3.2% in 2018-19. It is interesting to note that the contribution of government

has increased from 22.5% in 2004-05 to 40.6% in 2018-19, that of the household

OOP decreased from 69.4% to 48.2% whilst that of private health insurance

increased from 1.6% to 6.6% during the same period. The Central and State

governments’ health expenditure together account for just 1.3% of GDP which is

drastically below the 5% norm required to support the Universal Health Coverage

mission.

Several

evidences both quantitative and qualitative have consistently demonstrated that

the high level of household OOP health expenditure on treatment including

private health insurance premium is responsible for pushing people into poverty

Gumber (2000); World (2001); Van et al. (2006); Selvaraj and Karan (2009); Berman et al. (2010). It may be noted that private

health expenditure is higher than public expenditure across all major states.

The burden of OOP expenditure falls on a quarter or a third of the households

with incomes below the poverty line Deolalikar et al. (2008), which has impacted the reduction

in consumption expenditure on food and other essential items, increased

indebtedness, and growing untreated illness; and which could further lead to

gender bias in health-seeking behaviour Sen (2003).

Although

public health system has not equally spread-out geographically and has several

shortcomings in terms of providing both quantity and quality of services in India,

even then it has been evident from the previous National Sample Survey

Organisation (NSSO) Survey Rounds on Healthcare Utilisation that public health

services are the preferred option, particularly, for inpatient care Gumber (2002), Gumber (2021). Moreover, health outcomes,

especially, infant mortality, respond more to public health and local clinical

interventions than to hospital care Deolalikar et al. (2008), and these may vary across states.

This

paper presents the health and morbidity scenarios prevalent in India at four

time points using the NSSO surveys for 1986-87, 1995-96, 2004 and 2014 and thereby

examines the trends in the use of healthcare services separately for rural and

urban residents by public and private providers and their associated expenditure

on treatment as inpatient and outpatient. It further explores inter-state disparities in health

insurance enrolment/coverage and the extent of financial protection received by

insured households. These four survey rounds depict three important periods of

growth, namely the liberalization period of the 1980s, the period of fiscal

contraction in the 1990s that saw the decline in social spending Bhat and Jain (2006), Selvaraj and Karan (2009), the phase of globalization and the

launch of National Rural Health Mission in 2005. The paper also discusses

whether the states have made a notable progress towards achieving Universal

Health Coverage (UHC) goals in terms of improving equity in accessing

healthcare services and reducing financial hardship to meet the catastrophic

hospital treatment cost.

The

analysis took into account 17 of India’s largest

states; however, the computation of “All-India” averages included all major and

smaller states and union territories. There have been a few splits in states after

November 2000; hence we have added back Chhattisgarh to Madhya Pradesh,

Uttaranchal to Uttar Pradesh and Jharkhand to Bihar (which depicts a

pre-bifurcation scenario) in order to compare statistics

between NSSO Rounds. Furthermore, to account for inflation between survey

rounds we converted the cost of treatment in real terms by deflating the OOP

expenditure by the wholesale price index of pharmaceutical products at 1993-94

prices. Pharmaceutical prices are a significantly better reflection of the

actual rising cost of Indian healthcare services than the deflator based on

consumer price/wholesale price index for all commodities. The inflation rate of

pharmaceutical products has turned out to be higher than those for all commodities.

The wholesale price for pharmaceutical product is estimated to have increased

by 318 per cent against 240 per cent for prices of all commodities during the

period 1994-95 to 2011-12 (This is computed from RBI report on Wholesale Price

Index for various years under sub-category - Manufacture of

Pharmaceuticals, Medicinal Chemical and Botanical Products). Since much of the household’s

recurring health expenditure is incurred on purchasing the necessary drugs as

an inpatient/ outpatient, the use of price index for pharmaceutical items than

any other price index is more appropriate to demonstrate the financial burden of

rising healthcare expenditure on people seeking treatment in India.

The paper

is structured in five sections, including the introduction. Section 2 presents

a summary health scenario for India. The

healthcare utilisation pattern and associated cost of treatment for inpatient

and outpatient care for rural and urban residents are examined in Section 3. The

amount of household financial and health insurance protection is shown in

Section 4 for the major states. The summary and conclusions are presented in

the final section.

2. Health Scenario in India

With the

increasing attention towards achieving better population health, India has

significantly improved its health in terms of higher life expectancy and lower

levels of mortality over the last 50 years. According to health indicators provided

by the Central Bureau of Health Intelligence, Government of India. (2018), the birth rate decreased from 25.8

in 2000 to 20.4 in 2016 and the crude death rate decreased from 8.5 to 6.4

during the same period. Other health metrics, such as the infant and maternal

mortality rates, have also decreased over time as a result of the numerous

programmes included in previous Five Year Plans.

Between the 1970s and 2015, the infant mortality rate dropped from 120 per

1,000 live births by more than a third to 37. Similarly, the maternal mortality ratio decreased

from 400 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 1997-98 to 167 in 2011-13. In spite of these improved health outcomes, substantial disparities

in these health indicators continue to prevail among the states Balarajan et al. (2011).

In

contrast to other Asian nations like China, Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, the

Republic of Korea, and Sri Lanka, India's progress has lagged

behind. Due to the continuous epidemiological transformation and the

explosive increase of non-communicable diseases, the nation is also dealing

with the new challenge of a "double burden of disease." Even though

India has made tremendous progress in containing communicable diseases, their disease

burden on the nation is still significant. The prevalence of chronic

non-communicable diseases (NCDs), such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes,

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, malignancies, common mental disorders,

and accidents, has gradually increased along with the drop in morbidity and mortality

from communicable diseases. The National Health Policy 2015 states that

communicable diseases still account for 24.4% of all disease burden while

maternal and neo-natal ailments contribute to 13.8%. The NCDs (39.1%) and

injuries (11.8%) now constitute the bulk of the country’s disease burden.

The

government health spending in India must significantly grow in

light of the prevalent disease burden. The supply and financing of

various health services between the federal government and the states are

clearly demarcated. The financing and provision of curative healthcare are both

regarded as state matters. The Employees' State Insurance Scheme (ESIS),

primary healthcare facilities, and hospital services are entirely funded by the

state. The federal government fully

funds programmes for family welfare and medical education. The

majority of national disease control programmes are funded on a 50:50

share basis by the federal government and the states. However, the state's

contribution to the overall cost of these programmes turns out to be around

three-fourths, i.e., only basic inputs are shared equally. The state has to bear all the administrative cost including salaries

of the staff. The centre and states share equally the capital investment. The federal

government’s share is little over 40% in the total expenditure on medical

education and research, Broadly, thus the states fully manage and fund all

curative care services. This implies that State’s economic and financial conditions

as well as human resources have a direct impact on people’s health outcomes.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Key Health Financing Indicators for

India across NHA Rounds |

||||

|

|

NHA 2004-05 |

NHA 2013-14 |

NHA 2014-15 |

|

|

1 |

THE

as % of GDP |

4.2 |

4 |

3.9 |

|

2 |

THE

per capita (Rs) |

1201 |

3638 |

3826 |

|

3 |

CHE

as % of THE |

98.9 |

93 |

93.4 |

|

4 |

Total

Govt. Health Exp. As % of THE |

22.5 |

28.6 |

29 |

|

5 |

OOPE

as % of THE |

69.4 |

64.2 |

62.6 |

|

6 |

Social

security expenditure on health as per cent of THE |

4.2 |

6 |

5.7 |

|

7 |

Private

Health Insurance as a % THE |

1.6 |

3.4 |

3.7 |

|

8 |

External/Donor

Funding for health as per cent of THE |

2.3 |

0.3 |

0.7 |

|

|

Note: THE, CHE, and OOPE refer to Total Health Expenditure, Current Health

Expenditure, Out-of-Pocket Expenditure, respectively. Source: Government of India, 2017a,

National Health Accounts, 2014-15, p.11. |

|

||

Four key

facts emerge from key indicators presented in the NHA 2014-15 Table 1: (1) the increase in the share of

total government health spending to 29%; (2) the decline in OOP expenditure

from 69.4% in 2004-05 to 62.6%; and (3) 0.3% increase in the private health

insurance in 2014-15 and decrease by

the same amount in the social security expenditure compared to NHA 2013-14, but

with a notable increase compared to NHA 2004-05.

Against

this general backdrop, we examine in the following section the pattern of

health care utilisation across 17 major states over four survey rounds.

3. Pattern of Healthcare Utilisation and Cost of Treatment

3.1. Health Seeking Behaviour

The share

of illness episodes treated following on a medical advice is more an indicator of

the health-seeking behaviour of

consumers rather than of morbidity alone. The gender differences in the number

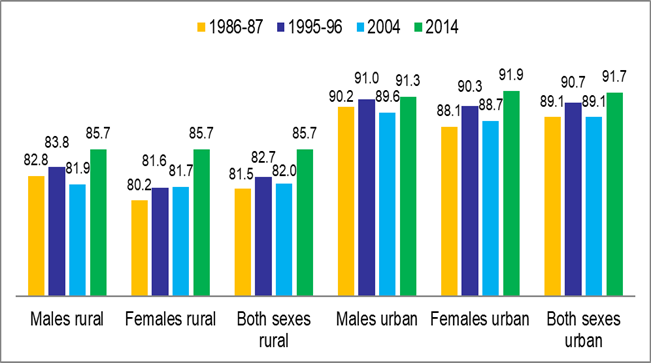

of illnesses treated, as shown in Figure 1, highlight the disparities between

rural and urban residents’ patterns of health-seeking behaviour. It

demonstrates that over the all-India, the proportion of illnesses treated in

urban regions for both genders continuously remained greater than those in rural

areas in all four rounds. This might be primarily because urban areas have

better access to medical facilities. In 2014, the rural-urban divide is found

to be smaller than that was in 1986–1987. Additionally, the gender difference

favouring men that was evident in the prior three rounds disappeared by 2014.

However, there are significant differences in health seeking behaviour between

men and women and between rural and urban areas and within select states

indicating positive and negative trends

over the four rounds.

Figure 1

|

Figure

1 Share of treated illnesses by sex and rural-urban

residence (%) |

When

compared to 1986–1987, there has been a little improvement in health seeking

behaviours across all-India for both sexes in 2014. Compared to 1986–1987,

rural areas of Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Odisha, Rajasthan,

and Tamil Nadu saw a noticeable improvement in health seeking behaviour in 2014

but Assam, Bihar, and West Bengal saw a decline. To our surprise, urban regions

in Assam, Bihar, Jammu & Kashmir, Odisha, and Punjab saw a decline in

health seeking behaviour whereas Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra saw a notable

improvement. In numerous states, particularly in rural areas, significant

gender disparities in ailment treatment have been noted (for more information,

see Gumber et al. (2017).

Despite

the diagnosis of illness, not everyone seeks medical help/assistance due to underlying

various socio-economic and cultural reasons. One of such reasons could be

because “respondents are known to underestimate both latent illness and chronic

illness and the perception of being ill is known to be dependent on cultural

factors, health awareness and access to care” Sundarraman and Muraleedharan (2015). The NSS surveys had collected

responses on the underlying reasons for ‘not seeking treatment’ for their ailments,

which could be due to: (a) non-availability of medical facility nearby; (b)

lack of faith; (c) lengthy waiting period; (d) financial reasons; (e) ailment

not regarded as serious; and (f) all other remaining reasons. In rural and

urban India, 15.4% and 1.3% of ailments respectively were not treated due to

lack of medical facility in 2014. The access to a nearby medical facility in

rural areas is a cause of concern. This suggests that a particular segment of

the population is denied access to basic primary healthcare.

The cost and

affordability of seeking care also plays a significant role in whether or not the poor and vulnerable individuals seek

medical attention. The number of respondents from rural and urban areas who

stated that they were unable to receive medical treatment during the NSS rounds

increased, which suggests that the gap in access to healthcare is expanding. It

has been noted that when there is an illness, the poor are more prone to

mention financial costs as justifications for skipping care. Both rural and urban

areas have seen an increase in this tendency over time Balarajan et al. (2011). According to a previous survey,

approximately half of those in the lowest quintile of spending avoid medical

care due to cost Gumber (1997). In some of the poorest states, the

main barrier to receiving treatment was financial. The proportion of untreated

illnesses in rural versus urban areas was significantly correlated, according

to state-level data, and the size of the correlation coefficient grew over

time, going from 0.643 in 2004 to 0.815 in 2014. This demonstrates unequivocally

that both rural and urban populations are impacted by state-level socioeconomic

conditions and the size of health infrastructure.

3.2. Public and Private Healthcare Providers

The

health of the impoverished is significantly influenced by access to public

health services. People might be forced to pay exorbitant fees or decide not to

use any health services at all if they don't have a choice Sen et al. (2002). It is critical to comprehend the

role played by public health providers in both inpatient and outpatient care in

a nation where private health spending hovers around 60% on average. The

private sector's involvement in the delivery of health care is expanding

quickly. The government actively promotes the entry of new private players by

offering tax breaks and subsidising land and capital for the construction of

hospitals. The inter-state examination of private health providers' growth

through time could not be done in this paper since there are no official records

for keeping track of hospitals, nursing homes, and clinics in rural and urban

locations. However, Hooda (2015) compiled the estimates from various

sources including NSSO Enterprise Surveys and estimated that there were 1.04

million private health enterprises in India in 2010-11 (See Table 2). Their number expanded

considerably in the post-liberalisation phase of 1990s which further got accelerated

exponentially in the 2000s specifically in urban locations (the share of

private health enterprises in rural locations in 2010-11 was just 18%).

The

public health sector has grown throughout time as well, although in the last 10

years the expansion of number of hospitals and beds increased substantially. This

was primarily motivated by the need to promote institutional births and lower

maternal and newborn mortality rates in order to achieve the global sustainable development

objectives agenda. The improvement indicator of people served per hospital bed

between 2004 and 2014 reflects some of these developments. It's interesting to

note that the expansion of the public health sector in rural areas has received

a much fairer allocation than the expansion of the private health sector, which

dominated in urban areas in the 2000s. According to the MoHFW's

National Health Profile, which is shown in Table 2 for the period 2004–14, the

quantity of public hospital beds in rural areas actually grew

at a much faster pace from 111,872 to 183,602 (64% rise) than in urban areas

from 357800 to 492177 (38% rise).

However,

the rate of growth of government hospital beds in rural areas varied greatly by

state; Jammu and Kashmir showed the largest decadal growth (222%), followed by

Rajasthan (182%), Tamil Nadu (176%), and Uttar Pradesh (172%). On the other hand,

during the same time period, Punjab and Gujarat saw a

decline in the number of hospital beds in rural areas. The National Rural

Health Mission financing has resulted in the misclassification or

reclassification of several urban hospitals as rural hospitals over time, and

some states have classified CHCs or upgraded PHCs as rural hospitals. As a

result, these results should be evaluated with caution. Because of this, we

have seen negative or insignificant growth rates in the number of government

hospital beds in urban areas during 2004-14 in various states, including Bihar,

Andhra Pradesh, and Rajasthan.

In Jammu

and Kashmir (196%), Uttar Pradesh (89%), Assam (81%) and Madhya Pradesh (72%),

there was a noticeable increase in the number of government rural and urban

hospital beds between 2004 and 2014. The population served per government

hospital bed increased in Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, and Bihar between 2004 and

2014 due to a decline in the number of government hospital beds in these

states. Bihar, Andhra Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh's public health

infrastructure, as measured by the population served per hospital bed, remained

deficient in 2014. On the other end of the spectrum, Himachal Pradesh, Kerala,

and West Bengal provided better health infrastructure.

3.3. Reliance on Public Health Services for Inpatient Care

The

information in Table 3 demonstrates that at all-India

level, the share of public providers in inpatient care for rural residents though

declined from 59.7% in 1986-87 to 41.7% in 2004 but exhibited improvement to 50.3%

in 2014. During 1986 to 2014, the decline in the share of public providers for

rural people is relatively less, compared to the decline witnessed for urban people

at all-India level. The share of public providers in urban India fell from

60.3% in 1986-87 to 35.5% in 2014. If we consider only 2004-2014 period, in

contrast to increase in utilisation for rural residents, the share of public

providers decreased slightly from 38.2% to 35.5% for urban residents.

At the

state level, the situation is more or less comparable

to that of all-India, where a general reduction between 1986–1987 and 2014 is

visible, although an increase in the share of public providers is noted between

the years of 2004 and 2014. Haryana,

Himachal Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Punjab, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, and

Uttar Pradesh all adhere to this pattern.

Even

while a few states recorded a decrease in the proportion of public providers in

1995–96 compared to 1986–1987, they subsequently consistently improved. This

group includes Madhya Pradesh and Assam. Public providers for inpatient

treatment for rural people have consistently decreased in Andhra Pradesh,

Gujarat, Karnataka, Kerala, and Maharashtra from 1986 to 1987. This is

concerning, as the percentage is lower than the 2014 average for all-India.

Andhra

Pradesh, Gujarat, Haryana, Karnataka, Kerala, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, and West

Bengal are the states that exhibit a constant fall in the share of public

providers for inpatient treatment in urban areas, similar to

the situation for all-India. The share of public providers in other

states—aside from Rajasthan and West Bengal—is lower than the national average.

Assam, Bihar, and Punjab are states that have experienced a revival over the

past ten years (2004–2014). While Uttar Pradesh's ranking stayed stable, Madhya

Pradesh's standing somewhat worsened in 2014 compared to 2004.

In rural

areas the increase in availability of government hospital beds over time

directly altered the healthcare utilisation pattern for rural residents. First of all, the inter-state correlation coefficient

between population served per government hospital bed with percentage share of

treated illnesses in 2014 was highly significant (-0.720 for rural and -0.611

for urban areas). Further, the population served per government hospital bed

was also significantly correlated (-0.619) with percentage change in share of

treated illnesses between 2004 and 2014 in rural areas; thus

signifying improvement in the access to government health facilities in a state

leads to better health seeking behaviour for their rural residents.

The

improvement (reduction) in reliance on public health facilities for inpatient

care particularly by rural populations in various states during 2004-14 is

directly associated with the expansion (contraction) of government health

infrastructure. Assam, Madhya Pradesh, Punjab, and Uttar Pradesh exhibited an

upward directional relationship, while Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat showed a

downward directional association. Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, and Kerala showed

a stable position, while the remaining states showed a mixed association. The

percentage share of public providers for inpatient care and variations in the

number of government hospital beds were generally shown to be positively

correlated at the state level (0.532 for 2004; 0.500 for 2014). We also

discovered a negative correlation between the number of private enterprises per

100,000 people (as shown in Table 2) and the percentage share of public

providers in inpatient care (-0.536 for 2004 and -0.593 for 2014) for 17 major

states. Hooda (2015) observed that the expansion of

private health enterprises at the state level was negatively correlated with

the reliance on public hospitals.

3.4. Share of Public Providers for Outpatient Care

For both

rural (28.3%) and urban (21.2%) people across all of India, the reliance on

public providers for outpatient care in 2014 was found to be significantly

lower than that for inpatient care. It is interesting to note that compared to

1986–1987, the proportion of public providers providing outpatient care to

rural households has improved in 2014. Assam, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha,

Punjab, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal are the states that are

following this trend, whereas the other nine states have experienced a fall.

Since 1986–1987, only Haryana has had a continuous fall. We have seen that two

of those nine states—Bihar and Maharashtra—restored reliance on public providers

between 2004 and 2014.

Even in urban

India, the percentage of public providers for outpatient treatment has

decreased from 1986–1987, though stagnation was seen between 1995–1996 and

2004. Since 1986–1987, the share of public providers in urban Karnataka and

West Bengal areas has consistently decreased. Since 2004, a few states,

including Assam, Kerala, Maharashtra, Punjab, and Uttar Pradesh, seem to have

resumed relying on public services. In urban areas of Andhra Pradesh, Bihar,

Gujarat, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha,

and Rajasthan, the proportion of public providers providing outpatient care has

decreased since 2004.

To some

extent in 2014, the public providers in outpatient care has played a dominant

role for either rural or urban or in both populations of hilly states of India

(Assam, Himachal Pradesh, and Jammu and Kashmir) and in Odisha. Additionally,

between 2004 and 2014, states that expanded their public health infrastructure

also saw an improvement in how many people used outpatient treatments. We

discovered a strong negative association (-0.521) between the percentage share

of public providers in outpatient care for urban areas in 2014 (as shown in Table 2) for 17 major states and the

population served by a government hospital bed.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Distribution of Government Hospital

Beds in Rural and Urban areas (2004 and 2014) and Private Health Enterprises

(2010-11) by Major States |

||||||||||||

|

Major States |

Government Hospital Beds** |

Population served per Govt. Hospital Bed** |

Private Health Enterprises* (2010-11) |

|||||||||

|

Rural Areas |

Urban Areas |

All Areas |

||||||||||

|

2004 |

2014 |

% Annual Change |

2004 |

2014 |

% Annual Change |

% Annual Change |

2004 |

2014 |

% Annual Change |

Number |

Per 100,000 population |

|

|

Andhra

Pradesh |

3005 |

7380 |

14.56 |

32106 |

12468 |

-6.12 |

-4.33 |

2297 |

4381 |

9.07 |

74603 |

88 |

|

Assam |

3000 |

7504 |

15.01 |

4382 |

5877 |

3.41 |

8.13 |

3800 |

2369 |

-3.77 |

7109 |

23 |

|

Bihar* |

4440 |

10129 |

12.81 |

23468 |

6837 |

-7.09 |

-3.92 |

4419 |

8130 |

8.40 |

79322 |

58 |

|

Gujarat |

11893 |

8945 |

-2.48 |

23163 |

18983 |

-1.80 |

-2.02 |

1564 |

2196 |

4.04 |

46111 |

76 |

|

Haryana |

1068 |

2454 |

12.98 |

6050 |

5210 |

-1.39 |

0.77 |

3185 |

3481 |

0.93 |

36312 |

143 |

|

Himachal

Pradesh |

2388 |

3328 |

3.94 |

5398 |

5448 |

0.09 |

1.27 |

817 |

795 |

-0.27 |

4302 |

63 |

|

Jammu

& Kashmir |

1820 |

5867 |

22.24 |

1475 |

3893 |

16.39 |

19.62 |

3212 |

1245 |

-6.12 |

4953 |

39 |

|

Karnataka |

7320 |

9884 |

3.50 |

33984 |

43138 |

2.69 |

2.84 |

1343 |

1154 |

-1.41 |

48178 |

79 |

|

Kerala |

7771 |

18082 |

13.27 |

18068 |

20318 |

1.25 |

4.86 |

1299 |

918 |

-2.93 |

34846 |

104 |

|

Madhya

Pradesh* |

10398 |

11542 |

1.10 |

12869 |

28657 |

12.27 |

7.28 |

3553 |

2532 |

-2.87 |

65779 |

67 |

|

Maharashtra |

11460 |

12398 |

0.82 |

30593 |

39048 |

2.76 |

2.23 |

2409 |

2277 |

-0.55 |

95684 |

85 |

|

Odisha |

4721 |

7099 |

5.04 |

8425 |

9584 |

1.38 |

2.69 |

2971 |

2505 |

-1.57 |

19782 |

47 |

|

Punjab |

4590 |

2900 |

-3.68 |

4383 |

8904 |

10.31 |

3.16 |

2824 |

2420 |

-1.43 |

40489 |

146 |

|

Rajasthan |

7465 |

21088 |

18.25 |

24615 |

10760 |

-5.63 |

-0.07 |

1910 |

2229 |

1.67 |

40490 |

59 |

|

Tamil

Nadu |

3318 |

9150 |

17.58 |

40249 |

55093 |

3.69 |

4.75 |

1498 |

1069 |

-2.86 |

43605 |

60 |

|

Uttar

Pradesh* |

9900 |

27146 |

17.42 |

25963 |

40764 |

5.70 |

8.94 |

5796 |

3472 |

-4.01 |

245662 |

117 |

|

West

Bengal |

10946 |

19684 |

7.98 |

47570 |

58882 |

2.38 |

3.43 |

1447 |

1170 |

-1.91 |

112470 |

123 |

|

All |

111872 |

183602 |

6.41 |

357800 |

492177 |

3.76 |

4.39 |

2336 |

1833 |

-2.15 |

1035497 |

86 |

|

Source: * NSS 2010-2011 (67th Round),

Unincorporated Non-Agricultural Enterprises; Hooda (2015: p14). ** National Health Profile for

various years, Centre Bureau of Health Intelligence, DGHS, MoHFW, Govt. of India, New Delhi. Notes: For a couple of states data

for government rural/urban hospital beds were not available for 2004 or 2014;

these were replaced by later years. |

||||||||||||

Table 3

|

Table 3

Share of Public Providers in Treated Illnesses, 1986-87 to 2014 |

||||||||||||||||

|

State |

Inpatient Care |

Outpatient Care |

||||||||||||||

|

Rural |

Urban |

Rural |

Urban |

|||||||||||||

|

1986- 87 |

1995- 96 |

2004 |

2014 |

1986- 87 |

1995- 96 |

2004 |

2014 |

1986- 87 |

1995- 96 |

2004 |

2014 |

1986 -87 |

1995- 96 |

2004 |

2014 |

|

|

Andhra Pradesh |

30.8 |

22.2 |

27.4 |

26.7 |

41.7 |

35.4 |

35.8 |

23.7 |

21.6 |

22.0 |

22.3 |

15.6 |

22.6 |

19.0 |

20.4 |

12.2 |

|

Assam |

89.8 |

69.2 |

75.0 |

91.7 |

82.4 |

63.0 |

55.2 |

62.6 |

53.0 |

29.0 |

35.6 |

84.3 |

29.6 |

22.0 |

29.1 |

44.6 |

|

Bihar |

50.1 |

24.1 |

21.7 |

56.1 |

46.8 |

31.9 |

26.5 |

49.1 |

16.9 |

13.0 |

7.8 |

13.9 |

18.0 |

33.0 |

16.9 |

12.3 |

|

Gujarat |

56.0 |

31.4 |

31.3 |

27.5 |

61.8 |

36.3 |

26.1 |

24.5 |

35.1 |

25.0 |

22.0 |

23.7 |

19.6 |

22.0 |

18.0 |

15.0 |

|

Haryana |

54.1 |

30.3 |

20.6 |

39.9 |

56.7 |

37.0 |

29.0 |

23.2 |

16.9 |

13.0 |

12.0 |

10.6 |

21.7 |

11.0 |

19.9 |

8.5 |

|

Himachal Pradesh |

88.0 |

86.5 |

78.1 |

77.3 |

78.9 |

91.3 |

89.7 |

75.5 |

60.7 |

39.0 |

68.6 |

43.3 |

47.7 |

48.0 |

86.1 |

79.4 |

|

Jammu & Kashmir |

96.5 |

97.7 |

91.2 |

94.0 |

96.1 |

95.9 |

86.4 |

82.2 |

59.8 |

44.0 |

53.8 |

48.4 |

47.4 |

28.0 |

50.9 |

41.0 |

|

Karnataka |

59.8 |

45.0 |

40.0 |

37.3 |

50.0 |

29.3 |

28.9 |

23.2 |

36.4 |

26.0 |

34.6 |

26.1 |

31.3 |

17.0 |

16.7 |

14.5 |

|

Kerala |

43.6 |

39.5 |

35.6 |

34.4 |

56.3 |

37.3 |

34.6 |

33.0 |

34.0 |

28.0 |

38.0 |

36.3 |

34.8 |

28.0 |

24.0 |

31.1 |

|

Madhya Pradesh |

80.4 |

40.4 |

57.2 |

67.4 |

79.0 |

54.7 |

48.7 |

48.2 |

27.1 |

23.0 |

22.7 |

29.5 |

25.9 |

19.0 |

24.8 |

24.0 |

|

Maharashtra |

45.8 |

30.9 |

28.7 |

26.9 |

49.4 |

30.7 |

28.0 |

24.4 |

36.5 |

16.0 |

17.4 |

20.2 |

35.3 |

17.0 |

11.7 |

14.6 |

|

Odisha |

90.7 |

84.2 |

79.1 |

84.2 |

82.2 |

77.9 |

73.1 |

61.4 |

52.7 |

38.0 |

56.8 |

75.5 |

47.9 |

34.0 |

58.3 |

54.4 |

|

Punjab |

49.2 |

37.7 |

29.4 |

36.1 |

52.0 |

26.5 |

26.4 |

31.7 |

13.4 |

7.0 |

17.6 |

16.8 |

15.6 |

6.0 |

18.9 |

22.5 |

|

Rajasthan |

81.0 |

63.3 |

52.1 |

65.6 |

86.5 |

72.1 |

63.7 |

58.0 |

56.1 |

36.0 |

45.5 |

44.1 |

57.5 |

41.0 |

53.9 |

29.1 |

|

Tamil Nadu |

56.9 |

40.4 |

40.8 |

45.4 |

58.2 |

34.2 |

37.2 |

32.6 |

38.7 |

25.0 |

30.7 |

42.3 |

35.5 |

28.0 |

22.1 |

28.6 |

|

Uttar Pradesh |

58.3 |

46.1 |

27.8 |

43.9 |

61.1 |

39.0 |

31.5 |

31.6 |

10.4 |

8.0 |

11.7 |

14.6 |

17.2 |

9.0 |

15.3 |

16.1 |

|

West Bengal |

91.9 |

79.9 |

78.7 |

77.5 |

75.9 |

71.3 |

65.4 |

55.1 |

19.6 |

15.0 |

21.1 |

22.5 |

25.3 |

19.0 |

21.4 |

14.8 |

|

All-India |

59.7 |

43.8 |

41.7 |

50.3 |

60.3 |

41.9 |

38.2 |

35.5 |

25.6 |

19.0 |

24.1 |

28.3 |

27.2 |

20.0 |

20.0 |

21.2 |

3.5. Provision of Free Health Services by the Public Sector

In the

delivery of free healthcare services for both inpatient and outpatient care,

private sector organisations have a very little role. As a result, free medical

care is available to people who use government facilities. Table 4 gives data on the proportion of

patients who got free hospital beds (as a proxy for free inpatient care) and

free medicine (as a proxy for free outpatient care) in order

to capture this element.

Similar to

the share of public providers in rural areas, free provision of beds in

inpatient care has decreased from 60.7% in 1986-87 to 37% in 2004 and then

improved to 47.3% in 2014 at the all-India level. In urban areas across all-India,

a same trend is also evident, but the percentage rise from 2004 to 2014 is just

2.6. However, as pointed out by Sundarraman and Muraleedharan

(2015), this pattern shows how public

health care consumption is geared towards the poor. Most states, particularly

for rural residents, follow this tendency, including Bihar, Haryana, Jammu and

Kashmir, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Punjab, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu,

Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal. No state has a steadily rising trend in its

free hospital bed offerings. While free bed provisions in Assam and Himachal

Pradesh continue to fall, they have stagnated in Odisha since 2004. In terms of

providing free beds for rural inhabitants, Assam outperformed all other states

in 1986–1987 with a 95.5% share; however, by 2014, this percentage had dropped

to just 50.6.

As was

already mentioned, in 2014, all of India saw a slight improvement in the free

availability of beds in urban areas. This pattern is seen in the urban areas of

Assam, Bihar, Gujarat, Haryana, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and

Punjab. The number of free beds available to the urban population in some

states has consistently decreased between 1986–1987 and 2014; these states

include Andhra Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir, Odisha, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, and

West Bengal. Even lower than the national average of 34.6% is the proportion of

free bed providing in urban Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Haryana, Karnataka,

Maharashtra, and Punjab. Again, no state exhibits a rising trend in the

provisioning of free beds.

Table 4

|

Table 4 Percentage of Patients Receiving Free Hospital Bed and Free Medicine

1986-87 to 2014 |

||||||||||||||||

|

State |

Free Hospital

Bed (Inpatient care) |

Free

Medicines (Outpatient care) |

||||||||||||||

|

Rural

Inpatient |

Urban

Inpatient |

Rural

Outpatient |

Urban

Outpatient |

|||||||||||||

|

1986- 87 |

1995- 96 |

2004 |

2014 |

1986- 87 |

1995- 96 |

2004 |

2014 |

1986- 87 |

1995- 96 |

2004 |

2014 |

1986- 87 |

1995- 96 |

2004 |

2014 |

|

|

Andhra Pradesh |

33.3 |

21.9 |

31.1 |

32.8 |

41.3 |

36.8 |

33.9 |

30.1 |

20.8 |

20.1 |

10.3 |

9.3 |

24.2 |

8.5 |

6.9 |

7.5 |

|

Assam |

95.5 |

76.5 |

60.2 |

50.6 |

76.1 |

58.0 |

41.3 |

42.9 |

31.0 |

12.6 |

2.7 |

2.6 |

10.5 |

6.0 |

5.6 |

3.9 |

|

Bihar |

47.7 |

20.0 |

22.4 |

48.2 |

56.5 |

38.9 |

30.4 |

41.8 |

5.2 |

1.5 |

0.2 |

1.1 |

26.6 |

10.4 |

3.7 |

0.4 |

|

Gujarat |

40.0 |

26.1 |

27.7 |

26.3 |

39.4 |

25.4 |

18.7 |

22.8 |

21.5 |

9.5 |

8.6 |

15.0 |

13.9 |

10.2 |

11.7 |

8.8 |

|

Haryana |

54.0 |

29.6 |

11.6 |

32.8 |

53.3 |

16.7 |

20.1 |

22.2 |

8.2 |

3.7 |

1.3 |

0.4 |

12.2 |

1.7 |

3.2 |

2.0 |

|

Himachal Pradesh |

86.5 |

79.0 |

74.1 |

70.0 |

77.3 |

71.0 |

80.5 |

48.3 |

24.1 |

4.5 |

3.6 |

0.9 |

8.8 |

6.8 |

9.0 |

0.5 |

|

Jammu &

Kashmir |

93.4 |

96.8 |

83.2 |

91.1 |

91.6 |

88.1 |

78.5 |

75.2 |

20.3 |

5.1 |

3.6 |

1.1 |

12.7 |

5.2 |

2.8 |

0.4 |

|

Karnataka |

58.8 |

37.8 |

38.2 |

32.9 |

36.6 |

25.3 |

28.2 |

20.8 |

26.5 |

16.3 |

14.6 |

4.9 |

25.4 |

8.2 |

4.8 |

3.4 |

|

Kerala |

45.1 |

37.5 |

33.6 |

35.4 |

45.2 |

31.7 |

29.5 |

31.3 |

29.8 |

9.3 |

11.1 |

14.4 |

25.4 |

8.7 |

6.6 |

9.3 |

|

Madhya Pradesh |

77.2 |

39.2 |

49.1 |

64.6 |

73.3 |

49.1 |

41.6 |

47.0 |

24.5 |

3.3 |

2.9 |

12.2 |

17.9 |

7.8 |

7.7 |

8.2 |

|

Maharashtra |

42.8 |

28.7 |

22.5 |

25.3 |

39.7 |

28.6 |

20.6 |

23.1 |

17.0 |

8.6 |

6.3 |

11.4 |

21.9 |

8.8 |

4.5 |

7.0 |

|

Odisha |

88.7 |

83.1 |

78.8 |

78.8 |

88.0 |

75.2 |

65.1 |

55.2 |

25.0 |

8.0 |

7.8 |

4.9 |

24.6 |

5.0 |

5.1 |

4.2 |

|

Punjab |

46.3 |

26.8 |

11.5 |

30.5 |

46.1 |

18.7 |

10.7 |

16.8 |

6.5 |

0.6 |

1.2 |

1.8 |

7.6 |

2.3 |

1.6 |

4.0 |

|

Rajasthan |

81.8 |

65.8 |

50.8 |

66.9 |

84.9 |

70.5 |

61.3 |

56.0 |

15.6 |

0.1 |

3.2 |

24.5 |

17.5 |

9.8 |

7.5 |

17.8 |

|

Tamil Nadu |

59.5 |

42.9 |

42.5 |

52.0 |

57.8 |

38.9 |

37.8 |

36.8 |

37.3 |

27.8 |

25.7 |

35.3 |

34.3 |

25.1 |

20.6 |

24.4 |

|

Uttar Pradesh |

59.1 |

39.8 |

16.8 |

39.8 |

56.1 |

32.6 |

21.8 |

34.7 |

6.0 |

1.8 |

2.2 |

3.0 |

10.5 |

4.0 |

4.5 |

6.7 |

|

West Bengal |

90.4 |

79.6 |

71.8 |

72.6 |

69.4 |

64.5 |

51.9 |

48.7 |

15.4 |

3.7 |

4.0 |

2.6 |

18.5 |

8.2 |

4.9 |

1.5 |

|

All-India |

60.7 |

41.6 |

37.0 |

47.3 |

55.2 |

38.2 |

32.0 |

34.6 |

17.5* |

7.7 |

6.4 |

9.4 |

19.7* |

9.3 |

6.8 |

9.3 |

|

Note: * denotes the All-India average based on the weighted average of 17

major states (states are weighted according to their share in the total

estimated hospitalised / ill persons). |

||||||||||||||||

3.6. Provision of Free Medicines

People

become prone to debt when they purchase medications, especially when they do so

frequently for a chronic illness. Provision of free medications would

significantly lessen this vulnerability. The NHA 2014–15 estimates that the

overall pharmaceutical spending in 2014–15 was Rs. 171025 crores, or 37.9% of

the current health expenditures (CHE). According to the NHA 2014–15,

pharmaceutical spending includes money spent on prescription drugs used in

medical interactions, money spent on self-medication (often referred to as

over-the-counter products), and money spent on pharmaceuticals used in

inpatient and outpatient care from prescribing physicians (Government of India,

2017a, p. 10). Prescription drugs made up Rs. 128887 crores, or 28.6%, of the

total Rs. 451286 crores of the CHE (Government of India, 2017a, p. 22).

Overall,

provision of free medicines during 1986-87 to 2014 decreased to 9.4% and 9.3%

in rural and urban areas at all-India level. Tamil Nadu is the only state where

more than 25% of rural patients have received free medicines; whilst this

percentage is lower for urban patients. Tamil Nadu and Rajasthan are the two

states where the percentage of patients reporting free medicines in 2014 is

high for both rural and urban populations, thanks to the drug procurement model

adopted in both the states.

According

to reports, more than 20% of rural patients in 10 states received free

medications in 1986-87. In 1995–96, there were only two states left (Andhra

Pradesh and Tamil Nadu), and by 2004 there was only one state left (Tamil

Nadu). However, Rajasthan and Tamil Nadu both appear on this list in 2014. In

Haryana, Himachal Pradesh and Jammu and Kashmir, less

than 1% of rural patients have reported getting free medicines and in another

seven states this was less than 5%.

In the

urban areas also, free provisioning of medicines which was at 19.7% in 1986-87

has decreased to 9.3% in 2014 (though better than the 6.3% in 2004). All the

states, including Tamil Nadu that is hailed as the model for other states to

follow in provisioning of medicines Lalitha (2009) have recorded steep decline in the

free provisioning of medicines in 2014 compared to 1986-87.

The fact

that the share of medications in inpatient and outpatient treatment is higher

than that of other components shows how much of a burden this is on the

population. According to Berman et al. (2010)'s analysis, the OOP expenditure to

cover healthcare expenditures, particularly those brought on by the lack of

free drugs, will further bankrupt the poor. Additionally, we observe a

discrepancy between the states that have improved urban services and those that

have improved rural services. Concerningly, "among various components,

highest expenditure was incurred on medicine both in public and private health

care institutions and this varied within a range of 38-66 percent" (p.31),

according to the National Health Accounts for 2004–2005. In public health care

facilities, around 66% of expenditures were made on medicine for the rural

population, compared to a slightly lower 62% for the urban population (Table 5). The cost of medicines in the

public sector has increased as a result of the lack of

medications for inpatient care.

Table 5

|

Table 5 Components of Inpatient Care Expenditure in

Public and Private Sector (%) |

||||||||

|

Type of

Hospital |

Sector |

Doctor's fee |

Diagnostic Test |

Bed etc. |

Medicine |

Blood etc. |

Food |

Total |

|

Private |

Rural |

26 |

9 |

17 |

40 |

3 |

5 |

100 |

|

Urban |

27 |

11 |

17 |

38 |

4 |

3 |

100 |

|

|

Public |

Rural |

4 |

12 |

4 |

66 |

4 |

9 |

100 |

|

Urban |

5 |

15 |

6 |

62 |

5 |

8 |

100 |

|

|

Source:

Government of India. (2005): Table 4.3, National Health Accounts,

2004-05. |

||||||||

3.7. Cost and Burden of Treatment

Without a

question, cost is the main factor to take into account

when deciding between a public and private institution, particularly for the

treatment of chronic and serious illnesses. The National Health Policy 2015

states that 60% of inpatient care and 80% of outpatient care are provided by

the private sector. The statistics in Table 6 show how much more expensive

private hospitals are as compared to public hospitals. Between 1986–1987 and

2014, the ratio of the cost of treatment for inpatient care at constant prices

nearly quadrupled (from 1.6 to 4.5) for rural residents and nearly doubled

(from 2.4 to 4.1) for urban residents at the national level in India. It is interesting

to note that the gap in inpatient costs between private and public providers in

rural and urban areas is narrowing down. Alternatively, it implies that the

cost of treatment between private and public hospitals is closing in the 2000s.

This could be due to the following factors:

(1) severe competition within the private sector has brought down prices for

their services; (2) public sector has started levying user charges in several

states which in turn increased their cost of treatment, almost equivalent to the

private sector; and (3) user fees has been implemented for the services

provided by the private sector under the scheme of public-private partnership. User fees for hospital

services were first instituted in Karnataka in 1996, followed by Odisha, Madhya

Pradesh, 1998, Uttar Pradesh, 2000, West Bengal, and Rajasthan in 2001 Shariff and Mondal (2009).

It would

be interesting to examine the cost trend for both rural and urban residents in

various states. Assam, Kerala,

Rajasthan, and Tamil Nadu all had an increase in the private-public cost ratio

for inpatient care for rural population during the course of

the four-year period (1986–87 to 2014). Implicitly, it shows the growing cost

difference between private and public hospitals in these states, which may be

related to the public hospitals' superior performance in these states. Does the

relative cost of therapy for rural individuals decrease over time in any

states? Several states reported lower costs in 1995–96 than in 1986–87, but

then increased costs in 2004 and 2014.

These

include West Bengal, Bihar, Gujarat, Jammu and Kashmir, Karnataka, Odisha,

Tamil Nadu, and Uttar Pradesh. For rural inhabitants requiring inpatient care,

we have observed an increase in costs between private and public providers in

14 of the 17 states since 2004. Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Tamil

Nadu have the largest cost ratio differences, with the private sector becoming

much more expensive. The Tamil Nadu situation is really odd.

Tamil Nadu has the greatest private-public cost ratio across all years. Only

Tamil Nadu has recorded a double-digit ratio, specifically in 2004 and 2014,

demonstrating the stark contrast between public and private providers for both

rural and urban populations (24.8 and 17.9, respectively). In contrast, these

ratios have remained stable throughout all four periods only in Gujarat for

both rural and urban populations

(ranged between 2.1 and 2.9 only).

Between

1986–1987 and 2014, the cost ratios for urban people increased in Andhra

Pradesh and Assam while being stable in Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Punjab, Uttar

Pradesh, and West Bengal. The majority of states have seen an increase in the cost of

inpatient care for urban inhabitants over the past ten years (2004–2014)

between private and public providers. The ratio across all of India increased

to 4.1 in 2014 from 3.1 in 2004, but it stayed below the norm in eight states

(Bihar, Haryana, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Punjab, Rajasthan,

and Uttar Pradesh). In contrast, the

cost ratio in Himachal Pradesh decreased from 3.4 in 2004 to 1.1 in 2014,

showing that the price of inpatient care for urban patients ended up being the

same at public and private hospitals.

Table 6

|

Table 6 Ratio of Cost of Treatment

between Private and Public Provider, 1986-87 to 2014 |

||||||||||||||||

|

State |

Inpatient |

Outpatient |

||||||||||||||

|

Rural |

Urban |

Rural |

Urban |

|||||||||||||

|

1986- 87 |

1995- 96 |

2004 |

2014 |

1986- 87 |

1995- 96 |

2004 |

2014 |

1986- 87 |

1995- 96 |

2004 |

2014 |

1986- 87 |

1995- 96 |

2004 |

2014 |

|

|

Andhra Pradesh |

2.2 |

3.8 |

2.5 |

4.0 |

5.2 |

5.4 |

9.1 |

8.4 |

1.8 |

4.1 |

1.8 |

2.4 |

4.2 |

2.3 |

2.6 |

1.8 |

|

Assam |

0.6 |

1.0 |

1.9 |

4.5 |

3.4 |

3.2 |

7.5 |

5.7 |

0.8 |

0.6 |

1.5 |

1.6 |

0.4 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

5.5 |

|

Bihar |

1.3 |

1.2 |

1.6 |

3.6 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

0.9 |

3.5 |

0.6 |

1.2 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

1.7 |

3.0 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

|

Gujarat |

2.3 |

2.2 |

2.8 |

2.1 |

2.9 |

2.2 |

2.6 |

2.9 |

1.6 |

2.3 |

1.6 |

3.1 |

1.5 |

1.7 |

2.7 |

1.5 |

|

Haryana |

1.5 |

1.3 |

0.5 |

2.7 |

1.9 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

2.7 |

1.6 |

0.8 |

1.4 |

1.1 |

1.9 |

0.5 |

1.1 |

1.6 |

|

Himachal

Pradesh |

1.8 |

1.1 |

2.4 |

2.2 |

3 |

3.2 |

3.4 |

1.1 |

0.8 |

NE |

0.7 |

0.9 |

1.3 |

NE |

1.7 |

0.9 |

|

Jammu &

Kashmir |

2.1 |

1.0 |

2.3 |

6.2 |

5.5 |

2.6 |

5.5 |

4.3 |

0.8 |

NE |

1.2 |

1.3 |

1.0 |

NE |

0.6 |

2.5 |

|

Karnataka |

2.8 |

2.3 |

3.1 |

5.2 |

3.3 |

2.9 |

6.2 |

6.4 |

1.8 |

2 |

2.1 |

1.4 |

1.4 |

1.4 |

1.8 |

1.5 |

|

Kerala |

1.6 |

1.7 |

2.1 |

7.4 |

2.6 |

1.5 |

1.9 |

6.8 |

1.5 |

1.6 |

1.3 |

1.9 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

1.2 |

1.9 |

|

Madhya Pradesh |

1.7 |

1.6 |

1.8 |

8.8 |

2.8 |

2.3 |

3.5 |

2.5 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

1.0 |

1.1 |

1.9 |

0.5 |

1.8 |

2.3 |

|

Maharashtra |

2.9 |

2.5 |

3.2 |

6.1 |

5.1 |

3.7 |

3.8 |

7.6 |

1.2 |

2.0 |

1.3 |

2.9 |

1.3 |

1.6 |

2.7 |

2.5 |

|

Odisha |

2.0 |

1.5 |

2.6 |

5.6 |

0.9 |

5.5 |

2.3 |

5.3 |

0.7 |

1.2 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.9 |

0.9 |

0.6 |

2.1 |

|

Punjab |

1.3 |

1.7 |

1.4 |

3.4 |

2.1 |

1.1 |

2.2 |

2.5 |

0.8 |

1.2 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

1.0 |

0.8 |

0.3 |

0.7 |

|

Rajasthan |

1.1 |

1.5 |

1.7 |

6.6 |

1.2 |

1.9 |

1.8 |

3.4 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

0.4 |

2.2 |

1.0 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

0.8 |

|

Tamil Nadu |

9.0 |

5.8 |

13.4 |

24.8 |

12.4 |

6.2 |

10.5 |

17.9 |

5.1 |

7.5 |

4.0 |

4.1 |

4.1 |

5.0 |

13.6 |

2.4 |

|

Uttar Pradesh |

1.4 |

1.1 |

1.2 |

4.1 |

1.5 |

1.3 |

2.4 |

2.2 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

2.1 |

1.0 |

0.7 |

0.9 |

1.54 |

0.8 |

|

West Bengal |

6.0 |

2.1 |

4.3 |

3.6 |

5.6 |

5.8 |

4.0 |

5.5 |

1.4 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

1.4 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

1.1 |

1.4 |

|

All-India |

1.6 |

2.1 |

2.8 |

4.5 |

2.4 |

2.4 |

3.1 |

4.1 |

0.7 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

0.9 |

1.2 |

1.44 |

1.4 |

For both

rural and urban populations, the private-public cost ratio for outpatient

treatment is not as high as it is for inpatient care. The increase in the cost

gap between rural and urban areas in India as a whole has

been slower during the time period under examination. It's interesting to note

that in 2014, the cost difference for outpatient care is greater for rural

people of Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Punjab, and Tamil Nadu compared

to urban residents. Tamil Nadu's outpatient costs are noticeably greater than

those in other states, similar to inpatient cost

ratios.

In some

jurisdictions, the outpatient cost of a private provider is less than the

national average, despite the fact that there is no

discernible pattern between rural and urban residents. In other words, in 2014,

both rural and urban people of Bihar and Himachal Pradesh found private

providers to be less expensive than public providers, whereas only urban

residents of Punjab, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh found this to be the case.

Although there are user fees paid in public hospitals in Odisha, Rajasthan, and

Madhya Pradesh, it can also be claimed that the private sector prices have not

increased as much as in other states like Tamil Nadu or Karnataka, despite the fact that it is partly reflecting on the general

health seeking conduct of people. It can also be because the public sector in

such states performs better. “A well-functioning public health care system not

only assures effective services to those at the lower end of the socio-economic

hierarchy but can also set a ceiling for the prices and a norm for the quality

in the private sector. It can, therefore, be a major anchor for equity overall

in the health service system. Inter-state comparisons within India appear to

confirm this as states with better public health services have lower prices in

the private sector” (cited in Sen et al. (2002)).

3.8. Cost of Inpatient Treatment

For each hospitalisation episode in 2014, the average cost of treatment

(including fees, medications, clinical and diagnostic tests, surgery, and

hospital bed charges in real terms) was Rs. 3965 for rural people and Rs. 7109

for urban people across the nation (Table 7). Due to the cost of

living and the type of care sought, it makes sense that urban patients'

treatment costs were greater than those of rural patients. For both rural and

urban populations across all of India, the cost of treatment has grown in real

terms for inpatient care (Table 7). Gujarat, Himachal

Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Punjab, Tamil Nadu,

and West Bengal are among the states that have noticed this tendency,

especially among rural residents.

Kerala,

Tamil Nadu, and West Bengal had the highest annual percentage change in costs

for rural residents between 1986 and 2014 (22.1, 17.3, and 11.3, respectively),

which is significantly higher than the national average of 5.4%. In contrast,

this was the lowest in states that are comparatively less developed (Bihar,

J&K, Assam, Rajasthan, Odisha, and Uttar Pradesh). It is important to note

that, with the exception of Odisha (where there has

been a marginal drop), rural inhabitants in the majority of states had a sharp

increase in the cost of inpatient care in 1995-96. In every other state, either

2004 or 2014 saw a decrease in treatment expenses. As a result, 2.8 is the

national average for the percentage of yearly change from 1995 to 2014,

compared to 1.8 from 2004 to 2014.

Between 2004 and 2014, the percentage of yearly change in inpatient

costs for rural inhabitants in five states—Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Kerala,

Maharashtra, and West Bengal—was higher than the national average. In Assam,

Bihar, Haryana, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh, rural residents have experienced

a negative yearly percentage change, indicating a decrease in the true cost of

treatment during 2014. Punjab reportedly had the highest inpatient cost for

rural people in 2014 (Rs. 7356), followed by Kerala (Rs. 5551) and Maharashtra

(Rs. 5369).

Similar to

the overall Indian trend, a rise has been seen in all four periods for the cost

of inpatient care for the urban population in 14 of the 17 states. Bihar, Jammu

and Kashmir, and Punjab are exceptions. Since the average yearly change for all

10 states between 1986 and 2014 was 8.1%, Tamil Nadu, Haryana, Andhra Pradesh,

Madhya Pradesh, Assam, and Kerala all saw very high growth rates of between 19%

and 21%. With the exception of Bihar, Jammu and

Kashmir, and Punjab, the percentage changes between 2004 and 2014 are negative.

Changes in the context of Gujarat, Haryana, and Rajasthan are less than the

national average of 3.9% among the remaining states where the change in cost is

positive. Overall, compared to other states, the cost of inpatient care was

greater for all inhabitants in Tamil Nadu, Punjab, and Haryana, while it was

lower in Jammu & Kashmir and Rajasthan.

At all-India

level, the cost of outpatient care for rural residents has increased from

Rs.141 (1986-87) to Rs.182 (2004) and then to Rs.176 (in 2014) (Table 8). But for urban residents,

outpatient costs have consistently increased from Rs.152 in 1986-87 to Rs.225

in 2014. At all-India level, the cost of outpatient care for rural residents

increased from 1986-87 to 2004 and then declined in 2014. Rural residents of Andhra Pradesh, Haryana,

and Karnataka exhibit this trend. Thus, there is an increase in treatment

expenses from 1986 to 2014, a drop from 1995 to 2014, and a flattening from

2004 to 2014. In some states, the cost

of outpatient care has decreased in 1995–1996 when compared to 1986–1987,

increased in 2004, and then decreased in 2014. This wave pattern is seen in

Kerala, Assam, Bihar, and Gujarat. In these situations, the cost in 2014 was

lower than the cost in 1986–1987, resulting in a negative annual change from

1986–2014. For rural residents, nine states—Haryana, Jammu and Kashmir, Karnataka,

Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal—have

seen changes that are more than the 0.9% national average.

In all

four time periods, outpatient costs for urban inhabitants in India as a whole increased, with an average yearly growth of 1.8%

from 1986 to 2014. A notable percentage change was observed in Assam, where

costs were at their lowest in 1986-87. Only Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Odisha (with

a very slight real-term increase nonetheless), and

Tamil Nadu have recorded a cost increase throughout the course of all four time

periods. Due to the sharp increase in costs in 2014, the annual change in

outpatient costs for urban residents in the recent ten years (2004-2014) has

increased by 2.8%, more than it did in 1986-2014 and 1995-2014. Assam, Haryana,

Himachal Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Tamil Nadu all experience a sharp increase in

cost in real terms.

People

should have enough insurance coverage to protect themselves from financial

risks due to the rising costs of treatment, especially for inpatient care, as

is covered in the section that follows

Table 7

|

Table 7 Cost of Treatment for

Inpatient Care, 1986-87 to 2014 (at 1993-94 prices) |

||||||||||||||

|

State |

Average Cost of Treatment (Rs) |

Annual Percentage Change |

||||||||||||

|

Rural inpatient |

Urban Inpatient |

Rural inpatient |

Urban inpatient |

|||||||||||

|

1986- 87 |

1995- 96 |

2004 |

2014 |

1986- 87 |

1995- 96 |

2004 |

2014 |

1986- 2014 |

1995- 2014 |

2004- 2014 |

1986- 2014 |

1995- 2014 |

2004- 2014 |

|

|

Andhra Pradesh |

1291 |

5273 |

3442 |

4092 |

1470 |

4008 |

5427 |

9228 |

8.0 |

-1.2 |

2.1 |

19.5 |

7.2 |

7.8 |

|

Assam |

900 |

1595 |

2225 |

1674 |

1655 |

3109 |

6087 |

10219 |

3.2 |

0.3 |

-2.8 |

19.2 |

12.7 |

7.5 |

|

Bihar |

2089 |

3166 |

3776 |

2804 |

1984 |

3055 |

5953 |

5738 |

1.3 |

-0.6 |

-2.9 |

7.0 |

4.9 |

-0.4 |

|

Gujarat |

1481 |

2184 |

3236 |

3852 |

2084 |

2729 |

4718 |

5678 |

5.9 |

4.2 |

2.1 |

6.4 |

6.0 |

2.3 |

|

Haryana |

2438 |

2645 |

5097 |

4941 |

1391 |

5362 |

7967 |

8836 |

3.8 |

4.8 |

-0.3 |

19.8 |

3.6 |

1.2 |

|

Himachal

Pradesh |

1719 |

2075 |

4705 |

5103 |

1862 |

2168 |

5223 |

7630 |

7.3 |

8.1 |

0.9 |

11.5 |

14.0 |

5.1 |

|

Jammu & Kashmir |

1163 |

2090 |

3015 |

2144 |

1148 |

2963 |

4195 |

3444 |

3.1 |

0.1 |

-3.2 |

7.4 |

0.9 |

-2.0 |

|

Karnataka |

1626 |

2458 |

3470 |

3713 |

2150 |

2947 |

4459 |

6307 |

4.8 |

2.8 |

0.8 |

7.2 |

6.3 |

4.6 |

|

Kerala |

796 |

1881 |

2249 |

5551 |

843 |

1581 |

3048 |

5137 |

22.1 |

10.8 |

16.3 |

18.9 |

12.5 |

7.6 |

|

Madhya Pradesh |

1205 |

1797 |

2706 |

3141 |

1041 |

2276 |

3760 |

6460 |

6.0 |

4.2 |

1.8 |

19.3 |

10.2 |

8.0 |

|

Maharashtra |

1628 |

2534 |

3436 |

5369 |

2682 |

3279 |

5365 |

8072 |

8.5 |

6.2 |

6.2 |

7.4 |

8.1 |

5.6 |

|

Odisha |

1353 |

1346 |

2460 |

2511 |

1282 |

3173 |

3545 |

5274 |

3.2 |

4.8 |

0.2 |

11.5 |

3.7 |

5.4 |

|

Punjab |

2524 |

4092 |

7158 |

7356 |

2795 |

4686 |

11354 |

8296 |

7.1 |

4.4 |

0.3 |

7.3 |

4.3 |

-3.0 |

|

Rajasthan |

1856 |

2492 |

4465 |

3417 |

1329 |

2583 |

4517 |

4575 |

3.1 |

2.1 |

-2.6 |

9.0 |

4.3 |

0.1 |

|

Tamil Nadu |

845 |

2330 |

3129 |

4802 |

1246 |

3227 |

6379 |

8467 |

17.3 |

5.9 |

5.9 |

21.5 |

9.0 |

3.6 |

|

Uttar Pradesh |

2266 |

3567 |

5211 |

4214 |

3266 |

4836 |

5285 |

8615 |

3.2 |

1.0 |

-2.1 |

6.1 |

4.3 |

7.0 |

|

West Bengal |

757 |

1605 |

2474 |

3070 |

1914 |

2639 |

4876 |

6824 |

11.3 |

5.1 |

2.7 |

9.5 |

8.8 |

4.4 |

|

All-India |

1605 |

2627 |

3408 |

3965 |

2227 |

3216 |

5272 |

7109 |

5.4 |

2.8 |

1.8 |

8.1 |

6.7 |

3.9 |

Table 8

|

Table 8 Cost of Treatment for

Outpatient Care, 1986-87 to 2014 (at 1993-94 prices) |

||||||||||||||

|

State |

Average Cost of Treatment (Rs) |

Annual Percentage Change |

||||||||||||

|

Rural Outpatient |

Urban Outpatient |

Rural Outpatient |

Urban Outpatient |

|||||||||||

|

1986- 87 |

1995- 96 |

2004 |

2014 |

1986- 87 |

1995- 96 |

2004 |

2014 |

1986- 2014 |

1995- 2014 |

2004- 2014 |

1986- 2014 |

1995- 2014 |

2004- 2014 |

|

|

Andhra Pradesh |

126 |

135 |

156 |

133 |

119 |

141 |

184 |

203 |

0.2 |

-0.1 |

-1.6 |

2.6 |

2.4 |

1.1 |

|

Assam |

158 |

124 |

184 |

120 |

23 |

148 |

239 |

547 |

-0.9 |

-0.2 |

-3.9 |

86.1 |

15.0 |

14.4 |

|

Bihar |

297 |

175 |

239 |

226 |

175 |

174 |

181 |

186 |

-0.9 |

1.6 |

-0.6 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

|

Gujarat |

154 |

129 |

181 |

154 |

175 |

179 |

240 |

146 |

0.0 |

1.1 |

-1.6 |

-0.6 |

-1.0 |

-4.3 |

|

Haryana |

136 |

155 |

240 |

182 |

134 |

340 |

140 |

299 |

1.3 |

1.0 |

-2.7 |

4.6 |

-0.7 |

12.6 |

|

Himachal Pradesh |

247 |

71 |

140 |

179 |

222 |

109 |

179 |

326 |

-1.0 |

8.4 |

3.1 |

1.7 |

11.1 |

9.2 |

|

Jammu & Kashmir |

192 |

154 |

179 |

255 |

154 |

122 |

245 |

265 |

1.2 |

3.6 |

4.7 |

2.6 |

6.5 |

0.9 |

|

Karnataka |

88 |

100 |

245 |

152 |

124 |

141 |

195 |

206 |

2.7 |

2.9 |

-4.2 |

2.4 |

2.6 |

0.6 |

|

Kerala |

115 |

112 |

195 |

156 |

96 |

98 |

110 |

190 |

1.3 |

2.2 |

-2.2 |

3.6 |

5.1 |

8.1 |

|

Madhya Pradesh |

141 |

127 |

110 |

217 |

220 |

308 |

190 |

241 |

2.0 |

3.9 |

10.9 |

0.3 |

-1.2 |

3.0 |

|

Maharashtra |

190 |

135 |

190 |

161 |

192 |

152 |

183 |

245 |

-0.6 |

1.0 |

-1.7 |

1.0 |

3.4 |

3.8 |

|

Odisha |

117 |

121 |

183 |

184 |

111 |

112 |

156 |

213 |

2.1 |

2.9 |

0.1 |

3.4 |

5.1 |

4.1 |

|

Punjab |

154 |

144 |

156 |

173 |

151 |

133 |

199 |

243 |

0.5 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

2.3 |

4.6 |

2.4 |

|

Rajasthan |

188 |

157 |

199 |

168 |

207 |

162 |

172 |

316 |

-0.4 |

0.4 |

-1.7 |

2.0 |

5.3 |

9.3 |

|

Tamil Nadu |

77 |

84 |

172 |

155 |

87 |

106 |

156 |

184 |

3.7 |

4.7 |

-1.1 |

4.2 |

4.1 |

2.0 |

|

Uttar Pradesh |

169 |

184 |

156 |

213 |

235 |

186 |

195 |

329 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

4.0 |

1.5 |

4.3 |

7.6 |

|

West Bengal |

98 |

107 |

195 |

150 |

164 |

112 |

182 |

180 |

2.0 |

2.2 |

-2.6 |

0.4 |

3.3 |

-0.1 |

|

All-India |

141 |

144 |

182 |

176 |

152 |

159 |

180 |

225 |

0.9 |

1.2 |

-0.4 |

1.8 |

2.3 |

2.8 |

4. Health Insurance and Financial Protection

India's

economy is expanding in the provision of health insurance coverage to its

people. Inpatient hospitalisation and certain medical care are covered by

health insurance companies in India. The Indian government has permitted

private companies in the insurance industry since 2000. However, according to the

National Health Policy 2015, 72% of all persons covered by insurance fall under