|

|

|

|

Original Article

PREDICTING MACHINE FAILURES AND SYSTEM SECURITY USING MACHINE LEARNING AND DEEP LEARNING ALGORITHMS

INTRODUCTION

In general, ML techniques must be used in

conjunction with other security measures to offer complete security for IoT

systems. ML algorithms and methods have been applied in various tasks,

including machine translation, regression, clustering, transcription,

detection, classification, probability mass function, sampling, and estimation

of probability density. Numerous applications utilize ML techniques and

algorithms, such as spam identification, image and video recognition, customer

segmentation, sentiment analysis, demand forecasting, virtual personal

assistants, detection of fraudulent transactions, automation of customer

service, authentication, malware detection, and speech recognition4.

In addition, IoT and ML integration can

enhance the devices of IoT levels of security, thereby increasing their

reliability and accessibility. ML’s advanced data exploration methods play an

important role in elevating IoT securityfr om only

providing security for communication devices to intelligent systems with a high

level of security5. ML-based models have emerged as a response to cyberattacks

within the IoT ecosystem, and the combination of Deep Learning (DL) and ML

approaches represents a novel and significant development that requires careful

consideration. Numerous uses, including wearable smart gadgets, smart homes,

healthcare, and Vehicular Area Networks (VANET), necessitate the implementation

of robust security measures to safeguard user privacy and personal information.

The successful utilization of IoT is evident across multiple sectors of modern

life6. By 2025, we expect that the IoT will have an economic effect of

$2.70–$6.20 trillion. Research findings indicate that ML and DL techniques are

key drivers of automation in knowledge work, thereby contributing to the

economic impact. There have been many recent technological advancements that

are shaping our world in significant ways. By 2025, we expect an estimated

$5.2–$6.7 trillion in annual economic effects from knowledge labor automation7. This research study addresses the

vulnerabilities in IoT systems by presenting a novel ML- based security model.

The proposed approach aims to address the increasing security concerns

associated with the Internet of Things. The study analyzes

recent technologies, security, intelligent solutions, and vulnerabilities in

IoT-based smart systems that utilize ML as a crucial technology to enhance IoT

security. The paper provides a detailed analysis of using ML technologies to

improve IoT systems’ security and highlights the benefits and limitations of

applying ML in an IoT environment. When compared to current ML-based models,

the proposed approach outperforms them in both accuracy and execution time,

making it an ideal option for improving the security of IoT systems. The

creation of a novel ML-based security model, which can enhance the

effectiveness of cybersecurity systems and IoT infrastructure, is the

contribution of the study. The proposed model can keep threat knowledge

databases up to date, analyze network traffic, and

protect IoT systems from newly detected attacks by drawing on prior knowledge

of cyber threats.

|

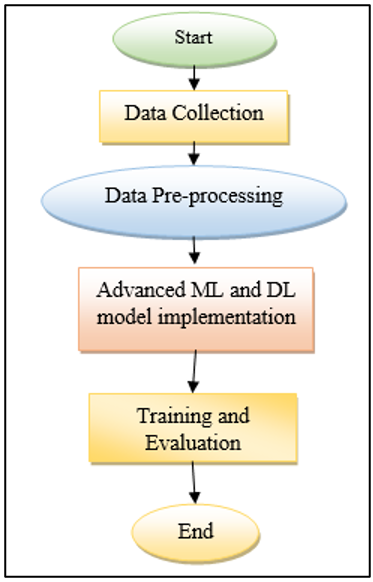

Figure 1

|

|

Figure 1 IOT

Applications |

The study comprises five sections: “Related

works” section presents a summary of some previous research. “IoT, security,

and ML” section introduces the Internet of Things’ security and ML aspects.

“The proposed IoT framework architecture” section presents the proposed IoT

framework architecture, providing detailed information and focusing on its

performance evaluation. “Result evaluation and discussion” section provides an

evaluation of the outcomes and compares them with other similar systems. We

achieve this by utilizing appropriate datasets, methodologies, and classifiers.

“Conclusions and upcoming work” section concludes the discussion and outlines

future research directions.

Nowadays, with the rise of the Internet of

Things (IoT), a large number of smart applications are being built, taking

advantage of connecting several types of devices to the internet. These

applications will generate a massive amount of data that need to be processed

promptly to generate valuable and actionable information. Edge intelligence

(EI) refers to the ability to bring about the execution of machine learning

tasks from the remote cloud closer to the IoT/Edge devices, either partially or

entirely. Examples of edge devices are smartphones, access points, gateways,

smart routers and switches, new generation base stations, and micro data centers.

|

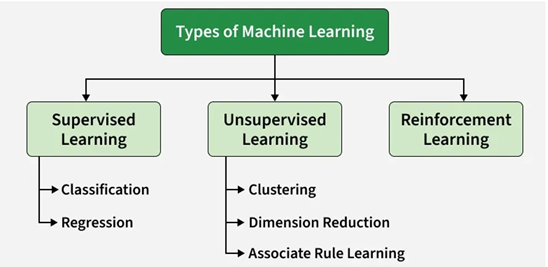

Figure 2 |

|

Figure 2 Types

of Machine Learning |

Some edge devices have considerable computing

capabilities (although always much smaller than cloud processing centers), but most are characterized by very limited

capabilities. Currently, with the increasing development in the area of MEMS

(Micro–Electro– Mechanical Systems) devices, there is a tendency to carry out

part of the processing within the data producing devices themselves (sensors) Kunst et

al. (2019),

Tessoni and Amoretti (2022),

Vollert et al. (2021),

O’Donovan et al. (2019) . There are certainly several

challenges involved in performing processing on resource-limited devices,

including the need to adapt complex algorithms and divide the processing among

several nodes. Therefore, in Edge Intelligence, it is essential to promote

collaboration between devices to compensate for their lower computing capacity.

Some synonyms of this concept found in the literature are: distributed

learning, edge/fog learning, distributed intelligence, edge/fog intelligence

and mobile intelligence Romeo et

al. (2020),

Boyes et al. (2018),

Arena et al. (2022) .

The leverage of edge intelligence reduces some drawbacks of running ML tasks

entirely in the cloud, such as:

High latency Kaushik

and Yadav (2023): offloading

intelligence tasks to the edge enables achievement of faster inference,

decreasing the inherent delay in data transmission through the network backbone;

·

Security and privacy issues Adhikari

et al. (2018),Zhou and Tham (2018): it is

possible to train and infer on sensitive data fully at the edge, preventing

their risky propagation throughout the network, where they are susceptible to

attacks. Moreover, edge intelligence can derive non-sensitive information that

could then be submitted to the cloud without further processing;

·

The need for continuous internet

connection: in locations where connectivity is poor or intermittent, the ML/DL

could still be carried out;

·

Bandwidth degradation: edge computing

can perform part of processing tasks on raw data and transmit the produced data

to the cloud (filtered/aggregated/pre-processed), thus saving network

bandwidth. Transmitting large amounts of data to the cloud burdens the network

and impacts the overall Quality of Service (QoS) Liu et al. (2018).

·

Power waste Carbery

et al. (2018): unnecessary

raw data being transmitted through the internet demands power, decreasing

energy efficiency on a large scale. The steps for data processing in ML vary

according to the specific technique in use, but generally occur in a

well-defined life cycle, which can be represented by a workflow.

Model building is at the heart of any ML

technique, but the complete life cycle of a learning process involves a series

of steps, from data acquisition and preparation to model deployment into a

production environment. When adopting the Edge intelligence paradigm, it is

necessary to carefully analyze which steps in the ML

life cycle can be successfully executed at the edge of the network. Typical

steps that have been investigated for execution at the edge are data

collection, pre-processing, training and inference. Considering the

aforementioned steps in ML and the specific features of edge nodes, we can

identify many challenges to be addressed in the edge intelligence paradigm,

such as (i) running ML/DL on devices with limited

resources, (ii) ensuring energy efficiency without compromising the inference

accuracy; (iii) communication efficiency; (iv) ensuring data privacy and

security in all steps; (v) handling failure in edge devices; and (vi) dealing

with heterogeneity and low quality of data. In this paper, we present the

results of a systematic literature review on current state-of-the-art

techniques and strategies developed for distributed machine learning in edge

computing. We applied a methodological process to compile a series of papers

and discuss how they propose to deal with one or more of the aforementioned

challenges.

To align with Industry 4.0, traditional

industrial automation approaches are evolving with the integration of new

elements. The Internet of Things (IoT) and Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS) play

crucial roles in enabling artificial intelligence and facilitating intelligent

manufacturing, leading to the creation of innovative products and services Kunst et

al. (2019). Companies

embracing this approach face increased competition in a dynamic market

environment, where simply increasing production capacity does not guarantee

success Tessoni and Amoretti (2022). Despite

various interpretations of industrial challenges, incorporating domain

knowledge into understandable and explainable models remains challenging Vollert

et al. (2021). DSS,

leveraging machine learning algorithms, aids in product design iterations and

facilitates effective policymaking, potentially enabling quicker recovery from

failures O’Donovan et al. (2019),Romeo et al. (2020). Furthermore,

leveraging vast amounts of data, particularly in predicting machine failures

and scheduling maintenance, allows industries to enhance performance and

autonomously manage product requirements Boyes et

al. (2018). However, many

manufacturing organizations struggle to embrace data-driven strategies due to

various challenges, particularly during the data preprocessing stage Arena et

al. (2022). As data

generated within Industry 4.0 proliferate, machine learning algorithms play a

vital role in extracting insights for improved understanding Kaushik

and Yadav (2023). Nowadays ML

can not only be used to diagnose problems, but can also be used to diagnose,

prognosticate, and forecast problems Adhikari

et al. (2018),Zhou and Tham (2018). In many

instances, machines exhibit signs of deterioration and symptoms before they

fail. Predictive maintenance (PdM) is a strategy used

by engineers to anticipate failures before they occur, relying on sensor-based

condition monitoring of machinery and equipment. However, implementing PdM requires substantial data and real-time monitoring,

posing challenges such as latency, adaptability, and network bandwidth Liu et al. (2018). Implementing

predictive maintenance at various stages of design offers several benefits but

also presents challenges. Advantages include increased productivity, reduced

system faults Carbery

et al. (2018), decreased

unplanned downtime, and improved resource efficiency Wang and Wang (2017). Predictive

maintenance also enhances maintenance intervention planning optimization Balogh

et al. (2018). However,

managing data from multiple systems and sources within a facility is

challenging, as is obtaining accurate data for predictive modelling Bousdekis et

al. (2019),Ferreira et al. (2017). Additionally,

implementing machine learning models and artificial intelligence faces

challenges such as collecting training data Xu et al. (2018),

LITERATURE REVIEW

Maintenance can be broken down into two

primary categories reactive maintenance and proactive maintenance. These are

the types of maintenance most performed in Industries. After a valued item has

had a breakdown, the purpose of reactive maintenance is to return it to working

order Ding and Kamaruddin (2015). Through the

utilization of preventative and predictive maintenance procedures, the purpose

of proactive maintenance is to forestall the occurrence of expensive repairs

and the early breakdown of assets. Corrective maintenance does not incur any

upfront costs and does not need any prior preparation to be carried out Susto and Beghi (2016). In most

cases, machines will experience some level of deterioration before finally

breaking down. It is possible to monitor the trend of degradation to rectify

any flaws that may exist before they cause any failure or the equipment to

break down. Since machine maintenance is only carried out when it is necessary,

this tactic results in greater levels of efficiency Susto and Beghi (2016). One such

strategy that assists us in predicting failures before they take place is known

as predictive maintenance (PdM). For this strategy to

work, the asset in question needs to undergo condition monitoring, which

employs sensor technologies to look for warning signs of deteriorating

performance or impending breakdown. The PdM allows

for the decision-making process to be examined from two different vantage

points: the diagnosis and the prognosis. According to Jeong et al. Jeong et

al. (2007),diagnosis is

the process of determining the underlying cause of a problem, whereas prognosis

is the process of estimating the likelihood that a failure will occur in the

future Lewis and Edwards (1997). Prognosis

maintenance policy is further divided into statistical-based maintenance and

condition-based maintenance. Industry 4.0 equipped digital model gives

maintenance staff the ability to schedule repairs more effectively because it

provides real-time equipment information. It is evident that predictive

maintenance is gaining more attention due to the recent advancements in data

collection through Industry 4.0technologies and data analysis capabilities

using evolutionary algorithms, cloud technology, data analytics, machine

learning and artificial intelligence. According to U car et al. Ucar et al. (2024) AI is the main

component of PdM for next-step autonomy in machines,

which can improve the autonomy and adaptability of machines in complex and

dynamic working environments. It is comprehensible that predictive maintenance

is getting additional consideration because of recent advancements in data

accessibility and analytics capabilities brought on by expanding research into

ML and AI algorithms. Machine learning is frequently used by researchers to

anticipate failure and improve output. Hesser and Markert Hesser

and Markert (2019) used an

Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model embedded within a CNC-milling machine to

monitor tool wear. Models like this one can be applied to older machinery that

can be used in Industry 4.0, as well as for research purposes. Kamariotis et al. (2024)found testing and validating

AI-based PdM systems face a challenge due to the

absence of standard evaluation metrics. This complicates the comparison of

system performance and assessment of accuracy and reliability. Various

evaluation metrics, including prediction accuracy, mean squared error, and

precision and recall, have been suggested by researchers to address this issue.

Sampaio et al. (2019) created an ANN model

based on vibration measurements for the training dataset. Additionally, they

compare the outcomes of ANN to those of Random Forest and Support Vector

Machine (SVM), two other ML techniques, and discover that ANN is superior.

Binding et al. [29] created Logistic Regression, XG Boost, and Random Forest

models to assess the machine’s operational status. By way of choice criteria,

Random Forest and XG Boost execute far improved as compared to Logistic

Regression, while all algorithms perform better than one another in terms of

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC). It was developed by Falamarzi et al. [30] to track forecast data and measure variation.SVM models predict curved segment gauge deviation

better than ANN models do for straight segment gauge deviation. To recognize

various rotary equipment scenarios, Biswal and Sabareesh [31] developed a Deep

Neural Network (hereafter referred to as DNN) and Convolutional Neural Network

(hereafter referred to as CNN). It can be used to monitor bearings in

production lines and enhance the monitoring of online conditions in coastal

turbines for wind energy. Data mining canbe used to

predict system behaviour based on historical data. Amodel-based

approach that heavily relies on analytical models to illustrate how the system

operates has a few benefits. In fields with an abundance of data, like

industrial maintenance, machine learning maybe used [32]. Actual results,

answers based on cloud-based, and new algorithms are all becoming more popular.

Quiroz et al. [33] applied the Random Forest technique for fault identification

and validity and reliability analysis with turned 98 %diagnostic accuracy rate.

Yan and Zhou [34] use TF- IDF (Term Frequency- Inverse Document Frequency) and

RF (Radio Frequency) data from aircraft speed and torque sensors to create ML

models for defect prediction. After extracting the features with TF-IDF from

the unprocessed data after the earlier flights, Random Forest had an accurate

optimistic degree of 66.67 percent and a percentage of false positives of0.13

percent. To predict wear and failures, Lee et al. [35] observed the spindle

motor and cutting machine using data-driven machine learning modelling. It has

been demonstrated that models using SVM and neural networks with artificial intelligence

can forecast system health and longevity with high accuracy. According to Palangi et al. [36], recurrent neural network (RNN) and

long short-term memory networks (LSTM) algorithms perform well with data that

is sequential, time-series data with dependencies that last along

time, and information from IoT flow sensors. LSTM and Naïve Bayes models

combined, according to the study, may effectively identify trends and produce

forecasts. The Naive Bayes anomaly detector was created by the LSTM model. Learning

through deep learning with Cox proportional hazard (CoxPHDL)

was developed in a research study to address the common problems of data

flexibility and filtering that occur when functional maintenance information is

analyzed [37]. The main goal was to develop an

integrated solution based on dependability analysis and deep learning. In

Gensler et al. [38] IoT application that combines solar panel prediction, the

Deep Belief Network (DBN).

The idea of security in IoT devices has been

recently articulated in studies that analyze the

security needs at several layers of architecture, such as the application,

cloud, network, data, and physical layers. Layers have examined potential

vulnerabilities and attacks against IoT devices, classified IoT attacks, and

explained layer-based security requirements8. On the other hand, industrial IoT

(IIoT) networks are vulnerable to cyber attacks.

Developing IDS is important to secure IIoT networks. The authors presented

three DL models, LSTM, CNN, and a hybrid, to identify IIoT network breaches9.

The researchers used the UNSW-NB15 and X-IIoTID

datasets to identify normal and abnormal data, then compared them to other

research using multi-class, and binary classification. The hybrid LSTM + CNN

model has the greatest intrusion detection accuracy in both datasets. The

researchers also assessed the implemented models’ accuracy in detecting attack

types in the datasets9. In Ref.10, the authors introduced the hybrid synchronous-asynchronous

privacy-preserving federated technique. The federated paradigm eliminates

FL-enabled NG-IoT setup issues and protects all its pieces with Two- Trapdoor

Homomorphic Encryption. The server protocol blocks irregular users. The asynchronous

hybrid

LEGATO algorithm reduces user dropout. By

sharing data, they assist data-poor consumers. In the presented model, security

analysis ensures federated correctness, auditing, and PP. Their performance

evaluation showed higher functionality, accuracy, and reduced system overheads

than peer efforts. For medical devices, the authors of Ref.11 developed an

auditable privacy-preserving federated learning (AP2FL) method. By utilizing

Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs), AP2FL reduces issues about data leakage during

training and aggregation activities on both servers and clients. The authors of

this study aggregated user updates and found data similarities for non-IID data

using Active Personalized Federated Learning (ActPerFL)

and Batch Normalization (BN). In Ref.12, the authors addressed two major

consumer IoT threat detection issues. First, the authors addressed FL’s unfixed

issue: stringent client validation. They solved this using quantum-centric

registration and authentication, ensuring strict client validation in FL. FL

client model weight protection is the second problem. They suggested adding

additive homomorphic encryption to their model to protect FL participants’

privacy without sacrificing computational speed. This technique obtained an

average accuracy of 94.93% on the N-baIoT dataset and

91.93% on the Edge- IIoT set dataset, demonstrating consistent and resilient

performance across varied client settings. Utilizing a semi-deep learning

approach, Steel Eye was created in Ref.13 to precisely detect and assign

responsibility for cyber attacks that occur at the

application layer in industrial control systems. The proposed model uses

category boosting and a diverse range of variables to provide precise

cyber-attack detection and attack attribution. Steel Eye demonstrated superior

performance in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, and Fl-score compared to

state-of-the-art cyber-attack detection and attribution systems. In Ref.14,

researchers developed a fuzzy DL model, an enhanced adaptive neuro-fuzzy

inference system (ANFIS), fuzzy matching (FM), and a fuzzy control system to

detect network risks. Our fuzzy DL finds robust nonlinear aggregation using the

fuzzy Choquet integral. Metaheuristics optimized ANFIS attack detection’s error

function. FM verifies transactions to detect block chain fraud and boost

efficiency. The first safe, intelligent fuzzy block chain architecture, which

evaluates IoT security threats and uncertainties, enables block chain layer

decision- making and transaction approval. Tests show that the block chain

layer’s throughput and latency can reveal threats to block chain and IoT.

Recall, accuracy, precision, and F1-score are important for the intelligent

fuzzy layer. In block chain-based IoT networks, the FCS model for threat

detection was also shown to be reliable. In Ref.15, the study examined

Federated Learning (FL) privacy measurement to determine its efficacy in

securing sensitive data during AI and ML model training. While FL promises to

safeguard privacy during model training, its proper implementation is crucial.

Evaluation of FL privacy measurement metrics and methodologies can identify

gaps in existing systems and suggest novel privacy enhancement strategies.

Thus, FL needs full research on “privacy measurement and metrics” to thrive.

The survey critically assessed FL privacy measurement found research gaps, and suggested further study. The research also

included a case study that assessed privacy methods in an FL situation. The

research concluded with a plan to improve FL privacy via quantum computing and

trusted execution environments.

IoT, security, and ML IoT attacks and security vulnerabilities

Critical obstacles standing in the way of

future attempts to see IoT fully accepted in society are security flaws and

vulnerabilities. Everyday IoT operations are successfully managed by security

concerns. In contrast, they have a centralized structure that results in

several vulnerable points that may be attacked. For example, unpatched

vulnerabilities in IoT devices are a security concern due to outdated software

and manual updates. Weak authentication in IoT devices is a significant issue

due to easy-to-identify passwords. Attackers commonly target vulnerable

Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) in IoT devices using code injections,

a man-in-the-middle (MiTM), and Distributed

Denial-of-Service (DDoS)16. Unpatched IoT devices pose risks to users,

including data theft and physical harm. IoT devices store sensitive data,

making them vulnerable to theft. In the medical field, weak security in devices

such as heart monitors and pacemakers can impede medical treatment. Figure 1

illustrates the types of IoT attacks (threats)17. Unsecured IoT devices can be

taken over and used in botnets, leading to cyber attacks

such as DDoS, spam, and phishing. The Mirai software in 2016 encouraged

criminals to develop extensive botnets for IoT devices, leading to

unprecedented attacks. Malware can easily exploit weak security safeguards in

IoT devices18. Because there are so many connected devices, it may be difficult

to ensure IoT device security. Users must follow fundamental security

practices, such as changing default passwords and prohibiting unauthorized

remote access19. Manufacturers and vendors must invest in securing IoT tool

managers by proactively notifying users about outdated software, enforcing

strong password management, disabling remote access for unnecessary functions,

establishing strict API access control, and protecting command-and-control

(C&C) servers from attacks.

IoT applications’ support security issues

Security is a major requirement for almost

all IoT applications. IoT applications are expanding quickly and have impacted

current industries. Even though operators supported some applications with the

current technologies of networks, others required greater security support from

the IoT-based technologies they use20. The IoT has several uses, including home

automation and smart buildings and cities. Security measures can enhance home

security, but unauthorized users may damage the owner’s property. Smart applications

can threaten people’s privacy, even if they are meant to raise their standard

of living. Governments are encouraging the creation of intelligent cities, but

the safety of citizens’ personal information may be at risk21,22. Retail

extensively uses the IoT to improve warehouse restocking and create smart

shopping applications. Augmented reality applications enable offline retailers

to try online shopping. However, security issues have plagued IoT apps

implemented by retail businesses, leading to financial losses for both clients

and companies.

PROPOSED METHODOLOGY

This study employs a quantitative,

experimental, and comparative research design to evaluate the efficiency of

Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) models in predicting machine

failures within an Industry 4.0 environment. The design emphasizes supervised

learning techniques, model benchmarking, hyperparameter optimization, and

rigorous performance validation using real-world industrial data.

|

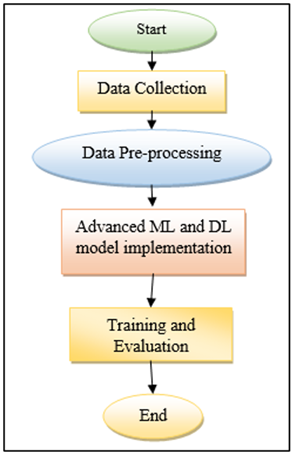

Figure 3 |

|

Figure 3 Proposed

Methodology Flowchart |

Two major analytical components structure the

research: ML-based classification models for machine failure prediction and

LSTM-based deep learning models for time-series behaviour analysis. Both

components are tested on a highly imbalanced predictive maintenance dataset

sourced from the UCI Repository. The experimental design allows systematic

comparison of models under identical conditions, ensuring fairness in

evaluating accuracy, detection capability, and robustness. This approach

supports developing reliable predictive maintenance solutions capable of

offering early warnings and improving industrial decision-making.

Data Source and Description

The study utilizes the Predictive Maintenance

Dataset from the UCI Machine Learning Repository, which contains comprehensive

machine-level operational data, including thermal readings, rotational speed,

torque, voltage levels, tool wear, and system load conditions. The dataset

reflects real industrial behaviour, combining normal operating records with

rare failure occurrences, resulting in a significantly imbalanced class

distribution. It includes several categories of machine failures, such as tool

wear, heat-related issues, overstrain, power failures, and random breakdowns.

Key variables consist of sensor-generated numerical features and operational

parameters, along with binary and multi-class failure labels. This rich,

multi-dimensional dataset provides an ideal testing ground for evaluating

predictive maintenance algorithms, enabling the study to assess how well ML and

DL models capture early deterioration signals and accurately classify impending

failures.

Data Preprocessing

A structured data preprocessing workflow was

implemented to ensure reliability and analytical accuracy. The dataset was

first examined for missing values and noise, though no missing entries were

found due to the dataset’s curated nature. Minor inconsistencies were addressed

through outlier detection and stability checks on sensor readings. Since

machine failures occur infrequently, the dataset suffered from severe class

imbalance, which was corrected using the SMOTE oversampling technique to

synthetically generate minority failure samples. Feature engineering steps

included scaling and normalizing numerical attributes, encoding categorical

variables, and applying a stratified train–test split to preserve class

proportions. These preprocessing techniques enhanced data quality, improved

model learning, and ensured that both ML and DL models were trained on

balanced, representative, and properly formatted inputs.

Machine Learning Models Used

The study implemented and compared seven

machine learning algorithms to identify the most effective model for predicting

machine failures. These included Random Forest, Logistic Regression, Support

Vector Machine, Naïve Bayes, Decision Tree, Gradient Boosting methods, and the XGBoost Classifier, which emerged as the primary performer.

Each algorithm was trained using standardized procedures and evaluated using

identical metrics to ensure fairness. To enhance model performance, Random

Search CV was employed for hyperparameter tuning due to its efficiency and

superior exploration of parameter space compared to Grid Search.

1) Random

Forest (RF)

Random Forest is an ensemble learning method

that builds multiple decision trees and aggregates their predictions to improve

accuracy and reduce overfitting. Each tree is trained on a randomly sampled

subset of data and features, making the model robust against noise and

variance. RF is highly effective for classification tasks, handles nonlinear

relationships well, and performs strongly in predictive maintenance scenarios

where sensor data contain complex patterns.

2) Logistic

Regression (LR)

Logistic Regression is a simple yet powerful

statistical classification model that estimates the probability of a binary

outcome using a logistic function. It is widely used due to its

interpretability and low computational cost. LR works best with linearly

separable data and provides insights into feature importance. Although less

effective for complex nonlinear patterns, it serves as a strong baseline for

machine failure prediction tasks.

3) Support

Vector Machine (SVM)

Support Vector Machine is a supervised

learning model that identifies an optimal hyperplane separating classes with

maximum margin. SVM performs exceptionally well in high-dimensional spaces and

can model nonlinear relationships through kernel functions. Its robustness to

overfitting makes it suitable for predictive maintenance datasets. Although

computationally expensive for large datasets, SVM delivers high accuracy when

distinguishing between normal and failure states in machine data.

4) Naïve

Bayes (NB)

Naïve Bayes is a probabilistic classifier

based on Bayes’ theorem, assuming independence among features. It is efficient,

fast, and performs well even with small datasets or noisy data. NB is

particularly useful in early-stage prediction tasks due to its low training

time. Although the independence assumption may not always hold, it remains

effective for machine failure classification where quick approximations of

failure likelihood are required.

5) Decision

Tree (DT)

Decision Tree is a rule-based classification

model that splits data into branches using feature thresholds, forming an

interpretable tree structure. It models nonlinear patterns and interactions

without requiring complex data preprocessing. DT is easy to visualize and

understand, making it useful for industrial applications. However, it is prone

to overfitting when used alone, which is why it often serves as a base model

for ensemble techniques.

6) Gradient

Boosting Methods

Gradient Boosting builds an ensemble of weak

learners—typically decision trees—in sequential stages, where each new model

corrects the errors of the previous ones. It optimizes predictive performance

by minimizing loss functions using gradient descent. This approach captures

complex relationships and delivers highly accurate results. Gradient boosting

is well-suited for predictive maintenance tasks that require sensitivity to

subtle failure patterns in sensor readings.

7) XGBoost

Classifier (Primary ML Model)

XGBoost

(Extreme Gradient Boosting) is an advanced and optimized boosting algorithm

designed for high speed, scalability, and superior performance. It incorporates

regularization, parallel processing, and optimized tree-building techniques,

making it highly effective for structured industrial datasets. XGBoost handles missing values, nonlinear relationships,

and class imbalance efficiently. Its exceptional accuracy, reliability, and

fast execution make it the leading model for machine failure prediction in this

study.

Deep Learning Framework

The study incorporates a deep learning

framework to capture temporal behavior and sequential

dependencies inherent in machine operating data. The primary model used is Long

Short-Term Memory (LSTM), a recurrent neural network architecture specifically

designed to learn long-term patterns from time-series sensor readings. LSTM effectively

identifies gradual deterioration trends, cyclical fluctuations, and hidden

temporal relationships that traditional ML models may overlook, making it

highly suitable for modeling machine failure

progression. To benchmark its performance, the study also employs a baseline

Artificial Neural Network (ANN) built on a standard multi-layer perceptron

structure. While ANN can learn complex feature interactions, it does not retain

sequential memory, resulting in lower accuracy compared to LSTM. However, the

study notes that ANN performance can improve with deeper architectures and

optimized hyperparameters. Together, these deep learning models provide a

comprehensive evaluation of temporal predictive capabilities in industrial

failure prediction scenarios.

Model Training and Validation

Model training and validation were carried

out using a structured approach to ensure accuracy, fairness, and reliability

in the performance comparison of all machine learning models. After the dataset

underwent preprocessing and balancing through the SMOTE technique, it was

divided into two subsets: 70% for training and 30% for testing. This split was

applied after oversampling to prevent data leakage and maintain the integrity

of model evaluation. The training set was used to fit each model and optimize

parameters, while the testing set served as an independent dataset to assess

generalization performance. This ensured that the models learned from a

balanced dataset but were evaluated on realistic, unseen distributions

representative of actual industrial conditions.

To measure predictive performance, multiple

evaluation metrics were applied, capturing both statistical accuracy and

failure detection capability. Accuracy provided an overall measure of correct

predictions, while Precision, Recall, and F1 Score offered deeper insights into

the model’s sensitivity to rare failure events. ROC-AUC Score evaluated the

models’ ability to distinguish between failure and non-failure classes across

thresholds, and the Confusion Matrix revealed specific misclassification patterns.

Together, these metrics ensured a comprehensive assessment of each algorithm’s

effectiveness in predictive maintenance scenarios.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The primary goal of the classification model

is to predict whether the machine will break down within the allotted time. It

is possible to forecast the residual usable life of the machine by utilizing

the regression model; nevertheless, the value of the prediction shifts with the

deterioration of the asset. They can go down significantly or up significantly.

However, if many assets need to be tracked, it will not be possible to do so on

an individual basis for each asset. As a result, a classification model has

been developed that provides certain early warnings with precision and within a

predetermined time frame. The performance metrics of several machine learning

models are displayed in Table 1. After obtaining the results for the various ML

models, the hyper parameters of these models will be modified to attain a

greater degree of precision and accuracy. As the tuning of hyper parameters was

discussed in the previous section and it is known that the "Random Search

CV" method is superior to the other commonly employed parameter

optimization techniques, we can move on to the next step. The effects of hyper

parameter tuning and optimization on the performance metrics of multiple

machine learning models are displayed in Table 2. Based on the data presented in

Table 2, it can be concluded that the XG Boost classifier is the most effective

of all the algorithms used in the modeling process.

It is primarily because it has the highest AUC score.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Evaluation

Metrics of a Classification Model. |

|||||

|

Model |

Accuracy |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-Score |

AUC-Score |

|

Logistic

Regression |

0.6453 |

0.4419 |

0.9625 |

0.6057 |

0.5331 |

|

KNN |

0.7168 |

0.6709 |

0.6831 |

0.6769 |

0.7007 |

|

SVC |

0.7293 |

0.7809 |

0.8027 |

0.7916 |

0.7138 |

|

Decision

Tree (Gini) |

0.6998 |

0.7713 |

0.7668 |

0.7690 |

0.7237 |

|

Decision

Tree (Entropy) |

0.6998 |

0.7713 |

0.7668 |

0.7690 |

0.7237 |

|

Bagging

Classifier |

0.8239 |

0.8859 |

0.5799 |

0.7010 |

0.7842 |

|

Adaptive

Boosting |

0.7786 |

0.8551 |

0.8657 |

0.8604 |

0.7814 |

|

Adaptive

Boosting |

0.7671 |

0.8520 |

0.8557 |

0.8538 |

0.7817 |

|

Random

Forest Classifier |

0.7964 |

0.9054 |

0.9234 |

0.9143 |

0.8202 |

|

XG

Boost Classifier |

0.8480 |

0.9460 |

0.9466 |

0.9463 |

0.8544 |

Table 2

|

Table 2 Evaluation Metrics

of Classification Model

After Hyper Parameters Tuning

Optimization |

|||||

Model

|

Accuracy

|

Precision

|

Recall

|

F1-Score

|

AUC-Score

|

Logistic Regression

|

0.6692

|

0.4693

|

0.9976

|

0.6383

|

0.5532

|

KNN

|

0.7407

|

0.6983

|

0.7182

|

0.7081

|

0.7208

|

SVC

|

0.7532

|

0.8083

|

0.8378

|

0.8228

|

0.7339

|

Decision Tree

(Gini)

|

0.7237

|

0.7987

|

0.8019

|

0.8003

|

0.7438

|

Decision Tree

(Entropy)

|

0.7237

|

0.7987

|

0.8019

|

0.8003

|

0.7438

|

Bagging

Classifier

|

0.8478

|

0.9133

|

0.6150

|

0.7353

|

0.8043

|

Adaptive Boosting

|

0.8025

|

0.8825

|

0.9008

|

0.8916

|

0.8015

|

Gradient

Boosting

|

0.7910

|

0.8794

|

0.8908

|

0.8850

|

0.8018

|

Random Forest

|

0.8203

|

0.9328

|

0.9585

|

0.9455

|

0.8403

|

XG Boost

Classifier

|

0.8719

|

0.9734

|

0.9817

|

0.9776

|

0.8745

|

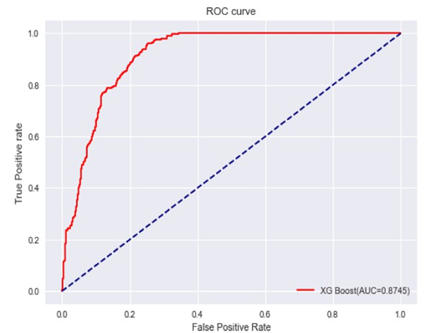

And the highest accuracy among all the

models. The ROC curve for an XG Boost model illustrates its ability to

discriminate between positive and negative classes across various threshold

values, serving as a pivotal tool for evaluating its classification performance.

The ROC-curve corresponding to the XG Boost model is depicted in Fig. 7, and

the confusion matrix for the XG Boost model applied to the validation dataset

is shown in Table 3.

|

Figure 4

|

|

Figure 4 ROC

Curve of XG Boost Model. |

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE WORK

Predictive maintenance appears as an essential method for accomplishing the goals of Industrial Revolution 4.0 in the worldwide industrial sector. The classification models created in this study greatly improve maintenance planning by providing early indications of asset breakdown. Critical tracking of multiple assets at the same time is now possible using these models. However, implementing predictive maintenance presents obstacles, such as addressing dataset imbalance and optimizing hyperparameters for greater performance. The growing applications of machine learning in all domains of science and technology attempts better prediction through applying wellknown models and comparing their performances. Though the models applied in this study are well known machine learning and deep learning models, the focus of this work was on trying to explore the models that ensure accurate prediction with an imbalance dataset. The researchers can apply the same set of algorithms for predicting machine failure in any type of industrial setting. Additionally, this study has developed a data-driven model for predicting machine failure and compared results from different machine learning algorithms. Practitioners and policymakers can take note that these algorithms require availability of large amount of error-free data to predict failure accurately. Many industries do not invest in data collection through IOT and sensor devices and face frequent breakdowns and interruption in their production lines. Analytics of collected manufacturing and operations data can help in saving huge amounts of time and money of manufacturing and service industries. Additionally, while a relevant problem, this paper does not focus on exploring why some algorithms and techniques are individually better than others. Still, the techniques considered represent the most used approaches, and the algorithms used for the meta-learner also provide a decent insight into the performance that can be expected. The SMOTE approach effectively resolved the imbalance in the dataset, allowing for the comparison of different machine-learning methods. The results show that the XG Boost Classifier outperforms other ML algorithms in terms of performance measures, even after hyperparameter adjustment. This emphasizes the significance of balancing datasets and fine- tuning model parameters to ensure accurate predictions. Furthermore, the use of deep learning models, notably Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), outperforms typical machine learning approaches. Although the accuracy of Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) initially fell short, layer-based optimization has the potential to improve. Despite its efficiency, predictive maintenance remains very expensive due to the use of advanced monitoring technology. Future efforts should focus on creating low-cost sensor technologies to reduce monitoring costs. Furthermore, future work will focus on optimizing hyperparameter tweaking in machine learning models. Furthermore, investigating a range of deep learning algorithms other than LSTM could improve the modelling process and provide more reliable forecasting capabilities. In conclusion, while predictive maintenance provides significant benefits for maintenance planning and efficiency, overcoming problems such as dataset imbalance and cost considerations is critical. Continued R&D efforts will help to advance and widely adopt predictive maintenance solutions in the industry. Predicting machine failures through predictive models, one of the goals of Industry 4.0, provides timely warnings of potential equipment failures and helps organizations to schedule maintenance activities. The results of this study demonstrate the effectiveness of machine learning and deep learning algorithms in predictive maintenance, enabling proactive maintenance interventions and resource optimization. It also contributes to the growing body of research on machine learning applications in industrial settings, advancing theoretical understanding and paving the way for further refinement of predictive maintenance methodologies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Adhikari, P., Rao, H. G., and Buderath, M. (2018). Machine Learning-Based Data Driven Diagnostics and Prognostics Framework for Aircraft Predictive Maintenance. In Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on NDT in Aerospace (24–26). Dresden, Germany.

Arena, S., Florian, E., Zennaro, I., Orrù, P. F., and Sgarbossa, F. (2022). A Novel Decision Support System for Managing Predictive Maintenance Strategies Based on Machine Learning Approaches. Safety Science, 146, 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2021.105529

Balogh, Z., Gatial, E., Barbosa, J., Leitão, P., and Matejka, T. (2018). Reference Architecture for a Collaborative Predictive Platform for Smart Maintenance In Manufacturing. In 22nd International Conference On Intelligent Engineering Systems (Ines) (Pp. 299–304). Ieee. Https://Doi.Org/10.1109/Ines.2018.8523969

Bousdekis, A., Mentzas, G., Hribernik, K., Lewandowski, M., von Stietencron, M., and Thoben, K.-D. (2019). A unified architecture for proactive maintenance in manufacturing enterprises. In Enterprise Interoperability VIII (307–317). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13693-2_26

Boyes, H., Hallaq, B., Cunningham, J., and Watson, T. (2018). The Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT): An Analysis Framework. Computers in Industry, 101, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compind.2018.04.015

Carbery, C. M., Woods, R., and Marshall, A. H. (2018). A Bayesian Network-Based Learning System For Modelling Faults In Large-Scale Manufacturing. In Ieee International Conference On Industrial Technology (Icit) (1357–1362). Ieee. Https://Doi.Org/10.1109/Icit.2018.8352377

Da Cunha Mattos, T., Santoro, F. M., Revoredo, K., and Nunes, V. T. (2014). A Formal Representation for Context-Aware Business Processes. Computers In Industry, 65(8), 1193–1214. Https://Doi.Org/10.1016/J.Compind.2014.07.005

Ding, S. H., and Kamaruddin, S. (2015). Maintenance Policy Optimization—Literature Review and Directions. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 76, 1263–1283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-014-6341-2

Ferreira, L. L., Albano, M., Silva, J., Martinho, D., Marreiros, G., Di Orio, G., and Ferreira, H. (2017). A Pilot for Proactive Maintenance in Industry 4.0. In 2017 IEEE 13th International Workshop on Factory Communication Systems (WFCS) (1–9). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/WFCS.2017.7991952

Hesser, D. F., and Markert, B. (2019).

Jeong, I. J., Leon, V. J., and Villalobos, J. R. (2007). Integrated Decision-Support System for Diagnosis, Maintenance Planning, and Scheduling of Manufacturing Systems. International Journal of Production Research, 45(2), 267–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207540600678896

Kaushik, A., and Yadav, D. K. (2023). Analysing Failure Prediction for a Manufacturing Firm Using Machine Learning Algorithms. In Advanced Engineering Optimization Through Intelligent Techniques: Select Proceedings of AEOTIT 2022 (pp. 457–463). Springer Nature Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-9285-8_44

Kunst, R., Avila, L., Binotto, A., Pignaton, E., Bampi, S., and Rochol, J. (2019). Improving Devices Communication in Industry 4.0 Wireless Networks. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 83, 1–12.

Lewis, S. A., and Edwards, T. G. (1997). Smart Sensors and System Health Management Tools for Avionics and Mechanical Systems. In 16th DASC. AIAA/IEEE Digital Avionics Systems Conference. Reflections to the Future. Proceedings 2 (8-5). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/DASC.1997.637283

Liu, Z., Jin, C., Jin, W., Lee, J., Zhang, Z., Peng, C., and Xu, G. (2018). Industrial AI Enabled Prognostics for High-Speed Railway Systems. In 2018 IEEE International Conference on Prognostics and Health Management (ICPHM) (1–8). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICPHM.2018.8448431

O’Donovan, P., Gallagher, C., Leahy, K., and O’Sullivan, D. T. (2019). A Comparison of Fog and Cloud Computing Cyber-Physical Interfaces for Industry 4.0 Real-Time Embedded Machine Learning Engineering Applications. Computers in Industry, 110, 12–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compind.2019.04.016

Romeo, L., Loncarski, J., Paolanti, M., Bocchini, G., Mancini, A., and Frontoni, E. (2020). Machine Learning-Based Design Support System for the Prediction of Heterogeneous Machine Parameters in Industry 4.0. Expert Systems with Applications, 140, 112869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2019.112869

Schmidt, B., and Wang, L. (2018). Cloud-Enhanced Predictive Maintenance. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 99, 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-016-8983-8

Schmidt, B., and Wang, L. (2018). Predictive Maintenance of Machine Tool Linear Axes: A Case from Manufacturing Industry. Procedia Manufacturing, 17, 118–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2018.10.022

Susto, G. A., and Beghi, A. (2016). Dealing with Time-Series Data in Predictive Maintenance Problems. In 2016 IEEE 21st International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA) (1–4). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ETFA.2016.7733659

Tessoni, V., and Amoretti, M. (2022). Advanced Statistical and Machine Learning Methods for Multi-Step Multivariate Time Series Forecasting in Predictive Maintenance. Procedia Computer Science, 200, 748–757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2022.01.273

Ucar, A., Karakose, M., and Kırımça, N. (2024). Artificial Intelligence for Predictive Maintenance Applications: Key Components, Trustworthiness, and Future Trends. Applied Sciences, 14(2), 898. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14020898

Vollert, S., Atzmueller, M., and Theissler, A. (2021). Interpretable Machine Learning: A Brief Survey from the Predictive Maintenance Perspective. In 2021 26th IEEE International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA) (1–8). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ETFA45728.2021.9613467

Wang, K., and Wang, Y. (2017). How AI Affects the Future Predictive Maintenance: A Primer of Deep Learning. In International Workshop of Advanced Manufacturing and Automation 32 (1–9). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5768-7_1

Xu, Y., Sun, Y., Liu, X., and Zheng, Y. (2018). A Digital-Twin-Assisted Fault Diagnosis Using Deep Transfer Learning. IEEE Access, 7, 990–999. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2890566

Zhou, C., and Tham, C. K. (2018). Graphel: A Graph-Based Ensemble Learning Method for Distributed Diagnostics and Prognostics in the Industrial Internet of Things. In 2018 IEEE 24th International Conference on Parallel and Distributed Systems (ICPADS) (903–909). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/PADSW.2018.8644943

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© IJETMR 2014-2025. All Rights Reserved.