ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

|

LEGACY OF PATRIARCHAL GOD AND THE POLITICS OF

MYTH-MAKING: LOCATING THE GENDERED POSITION IN RELIGIOUS VISUAL ART 1 Lecturer,

Department of English, Mahishadal Girl’s College, Vidyasagar University, West

Bengal, India

|

|

||

|

|

|||

|

Received 14 October 2021 Accepted 01 December 2021 Published 14 January 2022 Corresponding Author Abhijit Maity, amengvu@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v3.i1.2022.66 Funding: This research received

no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or

not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2022 The Author(s).

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution,

and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are

credited.

|

ABSTRACT |

|

|

|

This essay discusses how the imagination of women in India is framed

up by the gender-biased mythical representations. By looking at the mythical

representations that are circulated through centuries in many popular mages,

paintings and calendar-portraits, a discursive pattern can be found that has

positioned women in a secondary level, belonging to men. The family itself

becomes a political site in the process of normalizing women’s submissiveness

to men by comparing their actions with the Goddesses. By interrogating the

gendered position of Goddess like Lakshmi and her male counterpart Lord

Vishnu, this essay attempts to problematize with the mode of representation

in religious visual images. I conclude by arguing that these religious representations

in visual images have negative impact on the Hindu women, especially, in

rural areas, and thus, keep the unhealthy gender role intact in Indian

society. |

|

||

|

Keywords: Gendered Visual Culture, Mythmaking, Feminism and

Religion, Patriarchy in India 1. INTRODUCTION

“No man,

even in anger, should ever do anything that is disagreeable to his wife; for

happiness, joy, virtue, and everything depend on the wife. Wife is the sacred

soil in which the husband is born again, even the Rishis cannot create men

without women”. Adi Parva,

Book- 1.74.50-51 (Dutta 1895 , 108) A woman’s primary duty of being

truthful, sincere, and obedient to the others, especially to her male

counterpart, has always been considered as important qualities to be nurtured

and admired in the family. From the beginning of her upbringing within a

socio-cultural confinement, one is thrown into an ocean of moral lessons of

how to achieve those qualities that would later make her a ‘perfect’ woman to

the people in society. Religious lessons, which work as a strong discursive

backbone, are one of the vital chapters in the book of moral lessons. Visual representations

have stronger impact on an individual in compared to textual/scriptural

representations. This paper seeks to understand how the imagination of women

in rural India is framed up by the gendered visual representations. By

looking at the mythical representations that are circulated through centuries

in many popular mages, paintings and calendar-portraits, a discursive pattern

can be found that has positioned women in a secondary level, belonging to

men. The family itself becomes a |

|

||

political site in the process of normalizing women’s submissiveness to

men by comparing their actions with the Goddesses. By interrogating the gendered

position of Goddess like Lakshmi and her male counterpart God Vishnu, this

paper attempts to problematize with the mode of representation in religious

visual images. In conclusion, the paper argues that these religious

representations in visual images have negative impact on the Hindu women,

especially, in rural areas, and thus, keep the unhealthy gender inequality

intact in Indian society. The preference is given to rural areas because these

images and calendar representation, bear a special meaning in a rather

under-developed socio-cultural space.

2. Hindu Goddesses as Role Model

For decades, feminist scholarship in India has invested much energy in positioning the Hindu Goddesses and their literal as well as visual representations within a broader feminist framework. The pious presence of Hindu Goddesses has always been thought of as an instrumental agency in many social as well as political activism. The pantheon of Hindu Goddesses and their representations have been used as an inspirational source for women’s active engagements in private and public sphere. Locating the source of inspiration behind the political success of some of the famous, powerful, and transgressive female politicians in India and Nepal, Tawa Lama points out how the Hindu Goddesses were thought to be a symbolic resource in shaping the political life of women in both countries. Lama states, ‘The Hindu goddesses have been, in the last twenty years, the object of much interest in various circle, both in India and in the West. Ecofeminism and New Age spirituality have invoked her as a source of inspiration’ (2001, 6).

Here Tawa Lama seeks to understand the process of religious reworking in the history of Indian polity and how ‘the invocation of the goddess translates a political endeavour into a religious mission’ during India’s struggle for independence from the British rule. Referring to the female deities, who worked as epitomes of powerful feminine presence, he suggests two conclusions, ‘firstly, the Goddess seems to be both a symbolic resource which can be used by women in a political context, and the pillar of a Hindu “feminine mystique”. Secondly, her varying uses have a heuristic virtue as far as the political contexts in which they occur are concerned’ (2001, 20).

Debotri Dhar finds out in mythology the politics of desire and feminist agency that have been reworked in contemporary fiction. In her reading of Anita Nair’s psychological novel Mistress (2005), Dhar writes,

In comparison to other key Hindu goddesses such as Sita, whose devotion to their men is very much in keeping with societal mores, Radha therefore seems to stand out as an anomaly, an improbable “feminist” icon within mainstream mythology who challenges the very bedrock of patriarchy through her provocative agency. (2012, 2)

After getting an overview of the contemporary scholarship on Hindu mythology, it would be clear that there are many debatable issues come out of such studies regarding the Hindu Goddesses’ role as feminist agency in post-independent socio-political movements. Such as Sundar Rajan ’s famous inquiry in “Is the Hindu Goddess a Feminist” presents multiple political issues and social problems in contemporary India and their relationships with many Hindu female deities working as symbolic source of inspiration (2012). Lavanya Vemsani in her recent book Feminine Journeys of the Mahabharata: Hindu Women in History, Text, and Practice (2021) has pointed out how scholars have repeatedly used some of the terminology to mention the particularities of the Hindu Goddesses like ‘tooth Goddess/wild Goddess and breast Goddess/spouse Goddess/mother Goddesses’, and this is done either unknowingly or with ‘the natural tendency of the feminine to follow authority’ (8). Vemsani offers a detailed feminist study of the various sources of the episodes and incidents in the Mahabharata.

Again, another interesting study locates the mobilization of the Hindu Goddesses as powerful source of inspiration in many visual and verbal campaigns against gender-based violence Smears (2019). Pointing at the usefulness of employing Hindu Goddesses as powerful feminist symbol in contemporary India, Ali Smears offers a critical observation on the theological connection between the Goddesses and women, associated with a common possession of Shakti (power). Smears also states:

The Brahmanical tradition in particular views sexuality as a form of Shakti, but the uninhibited expression of sexual desire is seen as potentially dangerous, and inappropriate for women, as desire could lead a woman to engage in sex outside of socially sanctioned situations. Therefore, marriage is considered a way to control and direct a woman’s Shakti by controlling and directing her sexuality. Although all women are born as manifestations of Shakti, their Shakti can increase or decrease depending on specific actions. Motherhood within marriage is a way to direct women’s sexuality and power into a productive and auspicious expressions of Shakti. (2019, 2)

Most importantly, what is common in all these feminist approaches to the mythological or religious deities is that they have found in Hindu Goddesses the source of Shakti, energy, and inspiration for the devotees, and having ‘a uniquely popular, positive figure of feminine power’ (Lama 2001, 5). But little attention is paid to those rare visual representations of the Hindu Goddess that defines women in a secondary, subservient, and obedient position. Popular calendar images that are made largely available in rural areas are used as discursive tools to create and re-create a common, shared knowledge of women’s submissiveness in the family.

3. Obedient or Domestic Goddess

All the popular female deities in Hindu religion can be divided into two categories: innocent and violent Goddesses, or as Lama writes ‘benign Goddesses and fierce Goddesses, respectively characterized by a set of features such as their character, appearance, mobility, kinship, residence, worshippers, priest etc.’ (2001, 5). In the category of benign Goddesses, one can find names like Sita or Lakshmi, and Kali and Durga are the names usually known as fierce Goddesses. Among them, Lakshmi, Goddess of Fortune, is treated favourably in most of the Hindu families. Lakshmi is the emblem of all virtuous, likable qualities that have acquired an accepted version of ‘goodness’ in society. In the family, girls are told to be one like Lakshmi, to be free from sin, free from fierce or anger, not to be stubborn or individualist. The following mage shows the presence of Goddess Lakshmi sitting at the feet of her lord, the God Vishnu:

|

|

|

Figure 1 This

is a popular calendar image of Lakshmi sitting at the feet of Narayana, an

incarnation of Lord Vishnu, and pressing them for his comfort. Lord Vishnu is

one of the principal deities of Hinduism and has other names like Narayana or

Hari. Courtesy: Pinterest. |

|

|

|

Figure 2 This

calendar image shows Goddess Lakshmi sitting at Narayana’s (an incarnation of

God Vishnu) feet. Courtesy: Pinterest. |

|

|

|

Figure 3 This

portrayal shows Goddess Lakshmi holding one foot of Vishnu on her lap.

Courtesy: Pinterest. |

|

|

|

Figure 4 A

colourful painting of Goddess Lakshmi and Lord Vishnu shows Lakshmi holding

the feet of Vishnu on her lap in a manner of reverence. Courtesy: Pinterest. |

|

|

|

Figure 5 Another

popular calendar image shows Goddess Lakshmi touch Vishnu’s feet. Courtesy:

Pinterest. |

|

|

|

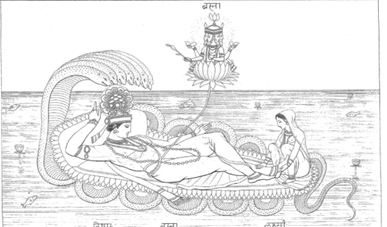

Figure 6 A rare line drawing shows Lakshmi sitting at the feet of Vishnu. The famous 19th century Orientalist Edward Moor compiled many such drawings and illustrations in The Hindu Pantheon published in 1810 (2012, 7). Source: https://www.istockphoto.com/vector/brahma-vishnu-and-lakshmi-gm180749496-24959658 |

|

|

|

Figure 7 This is a sculpture marble statue of Narayana and Lakshmi, largely sold in village fairs, and markets (also online stores). Courtesy: Artisans Crest. Source: https://www.artisanscrest.in/products/sculpture-white-marble-krishna-04. |

In the above figures, the ways Goddess Lakshmi is presented clearly show her subservient position. Different examples are presented here in order to demonstrate how single motif is multiplied and popularized throughout ages in various images, portraits, and paintings. Each figure shows the position of Lakshmi below the God Vishnu. A gender hierarchy is maintained in these visual representations by positioning woman at the feet of man. These religious visual images and the mythologies related to them are stored in socio-religious space in a recreation method. The presence of such representation showing the servitude of women determines ‘the cultural process’ of female subordination in Indian society (Visuvalingam 1996, 293). Goddess Lakshmi pressing the feet of lord Vishnu is taken by the devotees as a way to dedicate oneself not only to the service of her husband but also to the other elder male members in society. Lord Vishnu is represented as lying idly and receiving good care from his wife. So, the obedient or subservient position of the Goddess Lakshmi in visual representations works as a site of discursive backbone to create women’s subservient position in domestic space. In a patriarchal social structure, the above images exhibit the idea of man-made religion in which “men impose their ideas on women” by planting in them the notions of a pre-existed patriarchal superstructure (Mukhopadhyay 2020 , 2).

4. Conclusion

In rural or semi-urban social space, the cultural affectations of such visual representations and the popular mythological stories related to them have serious impact on the girls, who generally do not dare to ask questions to the elders. Most of the women in rural areas are brought up with the belief that they must possess qualities that are socio-culturally accepted as ‘good’. And being obedient or submissive to the men is the primary part to possess those ‘positive’ favourable qualities. These qualities are the genuine possession of Goddess Lakshmi. Those women who will not learn to possess those qualities cannot not be like Lakshmi but can be like her opposite incarnation, who is known as Alakshmi. In a family, Alakshmi is seen to embody all sinful, malicious, and disobedient qualities that are opposite to the qualities that Lakshmi possesses. Therefore, from the beginning, the female imagination is formulated or framed up by others to be, to behave, and to act like Lakshmi.

In his book Provincializing Europe, Dipesh Chakrabarty discusses the cultural appropriations of the concepts around the embodiments of Lakshmi and Alakshmi in Indian Hindu tradition. Chakrabarty observes that, as it is believed, if Alakshmi enters into family Lakshmi cannot prevail there. He also states,

The stories of Lakshmi and Alakshmi, however, were – and still are in many households – part of religious rituals that marked the daily, weekly, annual calendars of women’s religious activities in Hindu Bengali families. Ever since printing technology became available, books carrying stories of Lakshmi and Alakshmi, meant for use by women in ritual contexts, have been in continuous supply from the small and cheap presses of Calcutta (emphasis intended). (2000, 227)

So, the concepts around the activities that qualify women as ‘good’ or ‘evil’ in civil society are not new in Indian Hindu families, and religion has its primary source. Religious rituals around the stories of Lakshmi and Alakshmi are meant for women. It is interesting to note that those ‘small and cheap presses in Calcutta’ produce pamphlets or chapbooks that can easily be bought by those who are not economically strong. Those books, images, portraits are circulated and distributed among the people living even in the remote villages. Even still these calendar images and portraits are freely distributed by the sellers or storekeepers in rural areas on a particular day of each year. In most cases, the first day of Bengali calendar year is chosen by them to follow the religious ritual, in which all the customers who had not cleared their dues would be invited to get a packet of sweetmeats and a calendar image. In almost every household that calendar image is hung on the wall, projecting Goddess Lakshmi serving and sitting at the feet of Lord Vishnu. In these rituals, Goddess Lakshmi is naturally given a priority over other Hindu gods or Goddesses.

However, the family plays the religious as well as political role in shaping the imaginations or roles of the girls/women in society. These portraits are presented to them as visual texts which generally validate the verbal mythological stories they popularly share among the young girls. Thereby, these religious visual arts or images are used as cultural tools that shape a discursive pattern by defining the gender role within the family in particular and within the society in general.

RefErences

Chakrabarty, D. (2000). Provincializing Europe : Postcolonial Thought and Historical Différence. Princeton University Press.

Dhar, D. (2012). Radha' s Revenge : Feminist Agency, Postcoloniality, and the Politics of Desire in Anita Nair's Mistress. Postcolonial Text, 7(4), 1-18.

Dutta, M. N. (1895). A Prose English Translation of the Mahabharata. Elysium Press.

Lama, S. T. (2001). The Hindu Goddess and Women's Political Représentation in South Asia : Symbolic Resource or Feminine Mystique ? Revue Internationale de Sociologie, 11(1), 5-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/03906700020030956.

Moor, E. (2012). Hindu Gods and Goddesses : 300 Illustrations from "The Hindu Pantheon". Courier Corporation, Reprint & Revised.

Mukhopadhyay, A. (2020). The Authority of Female Speech in Indian Goddess Tradition : Devi and Womansplaining. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52455-5.

Smears, A. (2019). Mobilizing Shakti : Hindu Goddesses and Campaigns Against Gender-Based Violence". Religions, 10(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10060381.

Sundar, R. R. (2012). Is The Hindu Goddess a Feminist. Jura Gentium : Rivista Di Filosofia Del Diritto Internazionale E Della Politica Globale, 2, 1-16.

Vemsani, L. (2021). Feminine Journeys of the Mahabharata: Hindu Women in History, Text, and Practice. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-73165-6.

Visuvalingam, E. C. (1996). Bhairava and the Goddess Tradition, Gender and Transgression. In A. Michaels, C. Vogelsanger, & A. Wilke (Eds), Wild Goddesses In India And Nepal, 253-301.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2022. All Rights Reserved.