ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

dynamics-aktion- Pedagogical dynamics

proposal, useful for Design Studio teaching and beyond

1 Teacher at I Darte, Basque School of

Art and Higher School of Design, Spain

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

This paper [1], [2] is a continuation and a complement to the previous paper: #eindakoa#. (what we’ve done) A pedagogical method of Interior Design Projects’ method. [3] That paper developed a pedagogical method of design throughout a full course at a project Design Studio. This paper extends that previous paper and develops its pedagogical approach through a series of pedagogical dynamics and strategies, defined on a more precise and detailed scale. Each dynamic is artistically designed, almost like an action, to create a ‘learning event’ and teach the content of Design Studio through experience. These dynamics are inspiring, to such an extent that they can be transferred to any discipline. However, this article includes a specific theoretical support: a discussion and a comparative contrast with different models of the pedagogical method of the architectural project Design Studio. The first half

of the dynamics are developed to enrich a conventional class, prior to the

Covid-19 pandemic. The second half of the dynamics are developed in response

to the Covid-19 situation. They creatively exploit the possibilities of

different platforms for online teaching. |

|||

|

Received 09 April 2022 Accepted 15 May 2022 Published 30 May 2022 Corresponding Author Eneko

Besa, DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v3.i1.2022.118 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2022 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Dynamic, Pedagogy, Design Studio Teaching, Evaluation |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

This paper does not need an introduction beyond the direct presentation of the dynamics. They are shown as they are, starting with some descriptive images and the instructions for their development.

This narrative shows by itself the value of these pedagogical these dynamics of design pedagogy which, already in their very conception, are ‘designed actions’ or even ‘design in action’, and they constitute what we could call ‘educational performances’ within the classroom.

The

paper completes the description of each dynamic with the definition of the

objectives, as well as with scientific research and discussion, thus specifying

the content and intrinsic values, and describing the deep scope that these

dynamics can have despite their simplicity or their apparent naivety.

Figure 1

|

Figure

1 |

Some of

the dynamics (tear out, tectonic materials, sprint-projecting) were already

mentioned in the narrative descriptions of the previous paper. Other dynamics

are new, and, regarding their conception, it is necessary to appreciate the

influence of IRALE300, a Basque language training course, during autumn 2019 in

Vitoria-Gasteiz.[4] The

pedagogical experiences that the author experienced in that course are not

directly transferable to a design course, since they were linguistic

pedagogies. However, the dynamism and sense of everything received in that

course has been a source of inspiration and an exciting push to develop new

dynamics like those proposed here.

It is also necessary to thank the IRALE consultation service (kontsulta zerbitzua) for the impeccable work they have done reviewing almost all the Basque translations used in the course, as well as the generosity they have shown in making a linguistic revision of this article (Spanish version).

Without

further delay, here there are the dynamics.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Reconstructing the rubric /

Reconstruyendo la rúbrica / Errubrika berreraikitzen |

|

|

Context |

|

|

This dynamic is carried out just when we start the first exercise once

its statement has been explained. |

|

|

Procedure |

|

|

p1 |

We take the

rubric of a typical exercise. |

|

p2 |

We delete the

dividing lines, and we print it. |

|

p3 |

We trim it with

the guillotine, taking into account its content and also the difficulty that

making smaller pieces entails, separating certain contents, etc. |

|

p4 |

We divide the students

into groups of 4 or 5 and give them the dissected rubric. |

|

p5 |

Students

reconstruct the rubric and take a photo of their reconstruction proposal. |

|

p6 |

They

autocorrect themselves based on the answer that can be found on the blog of

the subject. |

|

p7 |

We all discuss

the different solutions and variables that have appeared. |

|

p8 |

From the

comments of the students, we discuss which ones may be admissible, and we

decide upon a new evaluation rubric. |

|

Materials |

|

|

m1 |

Printed rubric. |

|

m2 |

Guillotine or scissors. |

|

m3 |

Students’ phones to take pictures of

their solutions. |

|

m4 |

Mobile device or computer to check the

solution on the blog. |

|

Space |

|

|

e1 |

An arrangement of tables in groups to

carry out group work. |

|

e2 |

Tables’

arrangement that allows a subsequent dialogue without needing much movement,

avoiding distractions. |

|

Timing |

|

|

5’ |

5 minutes to explain the activity. |

|

25’ |

25 minutes for students to reconstruct

the rubric. |

|

20’ |

20 minutes for self-correction. |

|

5’ |

5 minutes break. |

|

50’ |

50 minutes to discuss different versions. |

|

Objectives |

|

|

obj1 |

Reading (something unusual nowadays). |

|

obj2 |

Personally, and actively integrating the

contents and, above all, the structure of the rubric. |

|

obj3 |

Interpreting and evaluating their own

solution. |

|

obj4 |

Discussing and

formulating alternative proposals to the teacher’s rubric. |

|

obj5 |

Actively participating

in the criteria by which they will be evaluated. |

|

Discussion |

|

|

As obj4 and

obj5 point out, from the beginning of the course, this approach recreates a

participatory and democratic design studio (hooks, 2021:30), to the point

that a shared discussion can reconfigure the teacher’s rubric. This

integrates Thomas A. Dutton’s deconstructive and critical approaches of the

‘hidden curriculum’ that can be seen in the work by Dutton (1987). However, as it

is possible to find hidden intentions in the curriculum, the students also

bring their unconscious prejudices with them. And so, without entering into

deeper discussions, but somehow echoing the theory of the primal horde

pointed out by Freud (1913-14:143-148), it is common for students, from the

first moment something is presented, to sound out the limits and weaknesses

that would make the authority ‘fall’. Anyone involved

in education experiences this, especially if the students are offered an

evaluation rubric. This is especially evident in the first few days of class,

a key moment in which all parties are measuring their strengths. In fact,

from this psychoanalytical approach, what students appreciate most is to have

an authority in front of them who does not knuckle under their unconscious

attempts to overthrow him/her. Therefore, the

main point is to be able to maintain a dialogue capable of integrating and

welcoming the conscious movement, as well as the unconscious motivations. In

this way, power is no longer understood as much as a hierarchical structure

to maintain or overthrow, but rather as the mutual projection of all

unconscious states or hidden curricula. Thus, the work of the teacher will

consist in exploring the ultimate motivations of both, the teachers

themselves and the students, to achieve the maximum integration of everyone

involved and all possible situations. In this manner,

we understand the design studio through the acceptance of the mutual transfer

and countertransference that occurs between teacher and student. These are

concepts that are close to the psychoanalytic field that we also find in

Ochsner’s study (2000), a study that approximates the Design Studio to the

therapist-patient relationship. In this case,

this deep interaction begins right from the first day of class with a dynamic

in which the teacher dares to offer a rubric that is open to reconstruction.

Thus, we avoid tedious situations of reading a technical document, such as a

quasi-institutional text like the rubric. We go for play and curiosity,

following the approaches offered in the book The Smile of Knowledge by

Fernández Bravo (2019). |

|

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 |

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 |

I

The

connotative meaning of the images of the collage is expressive.

However,

these images are not only selected due to their connotative meaning,

they are

also used taking advantage of other features.

·

Photos are limited and cropped providing a relationship with the

background.

·

These images participate in the form of the composition, expressing a

concept related to symmetry and antimetry.

T

The collage shows an expressive force.

The meaning of the pictures used in the collage can be

guessed, but it is not entirely clear why these images have been chosen.

Pictures are related to the meaning of the collage and

its strength, but their shape does not intervene in the composition of the

collage.

Pictures of the collage have been chosen in terms of

their connotative meaning and expressive force; however, their shape and their

suggestive spatial possibility have not been taken into account

Table 2

|

Table 2 Collaging the collage / Collageando el

Collage / Collagea collageatzen |

|

|

Context |

|

|

When we start this dynamic, the students

have just made the collage that is part of the ‘Aula-studio’ exercise defined in the previous article Besa (2019) (However, for organizational reasons, in

the 2019-2020 academic year, this dynamic was carried out at another time

during the course) |

|

|

Procedure |

|

|

p1 |

We choose an exercise which is already

finished, the collage. |

|

p2 |

We scan the collages of the students. |

|

p3 |

The teacher designs a presentation of the

work in which he presents their collages in pairs in each slide. (See the

attached image of one slide. The reader can also notice this in the

photographs about the development of the dynamic, specifically in the images

that the screens show). |

|

p4 |

The teacher assigns comments to each collage

in the slides. Comments based on an

interpretative and creative subjectivity, never a relativistic subjectivity.

The teacher designates each comment with a letter (A, B, Z, T, etc.) as the

title of the comment. |

|

p5 |

In the presentation the teacher does not

define which collage each comment corresponds to. Students have to discover

it. |

|

p6 |

Using the

title-letters, the students designate which comment each collage correspond

to. They write the letter on the

backside of a post-it. |

|

p7 |

We place the

pair of post-it notes on the board in order, making them correspond to the position of each of the

collages. Las parejas de post-it se van colocando en la pizarra o en un

panel en orden, haciéndolas corresponder con la posición de cada uno de los

collages. |

|

p8 |

After

completing the exercise, we flip the post-it and discover that each group,

thanks to the position of the letters, has created the title: “ZORIONAK

GUZTIOI!” which means “CONGRATULATIONS TO ALL!” (Logically, it is the teacher

who has previously rigged the order of the letters of the titles so that when

solving the exercise, they remain in the order that forms said title) |

|

p9 |

The evaluation

criteria implicit in the comments and the presentation of this dynamic can be

found later on the blog as part of the statement for the next collage. |

|

Materials |

|

|

m1 |

Presentation. |

|

m2 |

Projector or screen. |

|

m3 |

Post-it pads. |

|

m4 |

Panel or whiteboard to stick the post-its. |

|

Space |

|

|

e1 |

Tables placed in groups for group work. |

|

e2 |

A disposition that allows the view of the

projection and the panel. |

|

Timing |

|

|

50’ |

50 minutes for the dynamic. |

|

5’ |

5 minutes break. |

|

30’ |

30 minutes to comment and assimilate

previous steps. |

|

20’ |

20 minutes for personal questions. |

|

Objectives |

|

|

ob1 |

Introducing

oneself into a subjective, creative, interpretive work; distinguishing it

from the most immediate and prevailing objectivist keys. |

|

ob2 |

Differentiating

creative subjectivity from relativistic subjectivity. |

|

ob3 |

Appropriating

the specific way of thinking about the subject (as practically all the groups

are right in the result, the students understand that the criteria and

contents of the subject are not as ambiguous as at first, they might seem). |

|

ob4 |

Integrating and

assuming criticism in an open and enriched way. |

|

ob5 |

Distancing and

freeing oneself from the emotional-affective filter, in this case, this

dynamic provides a distance from the exercise itself that allows participants

to listen and integrate different comments. |

|

ob6 |

Obliquely

assimilating concepts and questions that are not so easy to understand in a

univocal or a direct way. |

|

ob7 |

Assuming the

evaluation criteria of the exercise in an experiential way. |

|

Discussion |

|

|

These dynamic designs

an experience capable of transmitting a content that is difficult to

assimilate in an explicit or exclusively rational way Ledewitz (1985). To do this, the

dynamic transforms one of the traditional processes of the design studio:

teacher-student criticism, or, as Schön Schön (1984) calls it,

teacher-student ‘reciprocal reflection-in-action’. In this case, this dymamic

extends the teacher-student relation involving the rest of the class within

it. Thus, this

activity aims to offer an alternative to the problems of the teacher-student

relationship that are typical of design studio, some of them compiled in the

publications by Frederickson (1990), Anthony (1987) and Ciravoğlu (2014): “The studio becomes the main medium of

architectural design education, and the conversation (mainly attributed as

critique) between student and the tutor becomes the means of this education.

Here the student is expected to learn by doing. However, the conversation,

which may be in one of the following forms as one-on-one, desk or jury

critique, is a very fragile one. According to Goldschmidt et al. (2010) many

students often misinterpret a critique of their work as waged against them in

person, which may result in anger, hurt feelings, or resistance. On the other

hand, many students, especially in the early stages of their studies, are

quite dependent on their teachers, and feel insecure until they receive from

the teacher both approval and explicit guidance for the advancement of their

projects. Even though the forms of critique are very determining, there is

too limited knowledge on the pedagogy of these critics. Schön (1984) identified that

learning in design studio begins with ill-defined problems (…)” Ciravoğlu (2014) As the students introduce themselves into

the game, they integrate and assume the criticism of their work, as well as

criticism of the work of their classmates. Students are no longer directly

face to face with the teacher's criticism. Thus, any possible resistance is

diluted. Even the revision of the exercise is not immediate, but rather the

students have to wait until the end, and thus, the dynamic provides necessary

time to integrate and assume comments and criticism. On the other hand, students receive the

teacher’s words indirectly, through the choice made by their classmates, from

a presentation in which their work is presented together with other works,

and thus, the content is approved and assumed by all. The end result, "ZORIONAK

GUZTIOI!" (‘Congratulations to all!’ because everyone is right), shows

us that the criticism and its contents are not so partial or biased. Coming

from the subjectivity of the teacher and, therefore, being inevitably unique,

these comments can be assumed, interpreted, and integrated by the whole

group. On the other hand, students are no longer

subjugated to or dependent on the teacher’s comments, but rather students

feel the need to interpret, elaborate and become active creators of the

conceptual content that allows them to self-evaluate their own projects. This last question, along with the rest,

is enhanced with similar dynamics that are collected later in this article. |

|

Table 3

|

Table 3 Evaluating evaluation / Evaluación de

la evaluación / Ebaluazioaren ebaluazioa |

|

|

Mark only one answer in each case: |

|

|

Context |

|

|

This dynamic takes place several days

after the evaluation criteria have been explained. |

|

|

Procedure |

|

|

p1 |

We prepare a

Google form related to the evaluation criteria of the course. |

|

p2 |

We send it to

the students. They can fill in it is consulting the evaluation criteria of

the course in the blog. |

|

p3 |

We design this

Google form with two answers per question. A correct answer and another

bizarre answer, reflecting attitudes and situations that, unfortunately,

students sometimes show, but they will never assume as their own

attitudes. |

|

p4 |

Using

playfulness, the students get trapped, they have no other options than: ·

Choose the correct answer, committing

themselves and acknowledging that they have read and understood the

evaluation criteria. Also, they assume that they understand that other

attitudes are not appropriate. ·

Not answer the form, so they cannot later

claim that the evaluation criteria have not been made clear. ·

Only people who will have no problems

passing can dare other alternatives, and thus, a student once even asked:

"Can I perform an answer?" |

|

Materials |

|

|

m1 |

Google Forms application or another

analogue platform. |

|

m2 |

Mobile device or computer to answer the

test and consult the blog. |

|

Space |

|

|

e1 |

Online space |

|

e2 |

For the future: search for the most

suitable platform, which could offer the best environment and design. |

|

Timing |

|

|

5’ |

5 minutes to explain the dynamic. |

|

50’ |

50 minutes to do the test. |

|

5’ |

5 minutes break. |

|

30’ |

30 minutes to

comment the sense and objectives of the test and clarify any doubts regarding

the evaluation criteria. |

|

Objectives |

|

|

ob1 |

Dynamically

explaining, searching for alternatives to the traditional class. |

|

ob2 |

Integrating

digital platforms and other means of communication subverting their immediate

application (it is not simply a matter of transferring the traditional class

to the online space, but rather it is about ‘taking advantage’ of its

possibilities). |

|

ob3 |

Using jokes and

caricatures, we reflect on and bring out attitudes that at first sight we do

not want to recognize, but that deep down are an active force. |

|

ob4 |

Taking

responsibility of our own decisions. Integrating one’s stance, reducing the

exculpatory tendency that is projected outwards. |

|

Discussion |

|

|

With this

dynamic, we again return to the issues raised about the ‘hidden curriculum’

(Dutton, 1987:16). As it has been pointed out in the first dynamic, education

largely consists of working, more or less directly or indirectly, on what is

happening in hidden strata or, more technically, unconscious layers. With this test,

we try to generate a dynamic in which unconscious movements are revealed

indirectly, obliquely, through playfulness. On the one

hand, the first thing that this dynamic reveal and explains is the approach

to the subject, ‘trying to define and fine-tune a subject that, in the case of Design

Studio, is not so easily objectifiable’; leaving

room for errors, accidents, repetitions, and recoveries, while leaving the

responsibility to students to take on board the decisions taken. In the same way

that it does with the curriculum, the test also ‘uncovers’ attitudes of the

students that are more or less unconscious. I can declare that some of the

most absurd questions on the test are caricatures, just a ‘little’ exaggerated,

of attitudes that I have had to face during all these years dedicated to

education. |

|

Figure 4

|

Figure 4 |

Table 4

|

Table 4 Evaluating a project (sei zentzu) /

Evaluando un proyecto (sei zentzu) / Sei zentzu proiektuaren ebaluazioa |

|

|

Context |

|

|

We perform this

dynamic while the students are developing the exercise ‘Sei Zentzu’ defined in the previous article Besa (2019). In that

exercise, students must overcome the difficulty of designing an action, pure

action and not decoration or physical design, in a place that is also

generic. This dynamic constitutes an evaluative stage once the first attempts

to solve the exercise have been made. |

|

|

Procedure |

|

|

p1 |

The teacher

classifies in groups the projects done by students. All standard errors are

collected in each group. In each group there is at least one project that represents

a standard error. |

|

p2 |

Before the

students enter the classroom, the teacher arranges projects on the tables in

groups. |

|

p3 |

Students come

into the classroom and place themselves in a group that does not include

their work. Students are thus randomly distributed in groups. |

|

p4 |

Working in

groups they evaluate each one of the projects using the evaluation criteria

of the exercise, and they place a post-it on each project with a comment

written by all of them. |

|

p5 |

Once they have

placed their comments, they also place the comments that the teacher had made

previously, which he/she had hidden under the tables. They compare their

comments with those of the teacher. |

|

p6 |

Groups rotate

through the classroom, and thus they see the comments that other classmates,

as well as the teacher, have made about their work and about other projects. |

|

p7 |

Once the

objectives and the standard errors have been assimilated through this

dynamic, the next day we give the students another opportunity and repeat the

exercise. |

|

Materials |

|

|

m1 |

Projects by students |

|

m2 |

Post-it pads. |

|

m3 |

Tape. |

|

Space |

|

|

e1 |

Tables arranged in groups. |

|

e2 |

Students’

groups should have the possibility to rotate. In our case, despite the

limited space, we managed to achieve an arrangement that allowed a perimeter

tour and rotation. |

|

Timing |

|

|

5’ |

5 minutes of indications. |

|

35’ |

35 minutes for groups to make their

comments. |

|

10’ |

10 minutes to distribute teacher’s

comments. |

|

5’ |

5 minutes break. |

|

30’ |

30 minutes to see the rest of the

projects and comments. |

|

20’ |

20 minutes for sharing. |

|

Objectives |

|

|

ob1 |

Evaluating and

co-evaluating one’s own work through the work of others. |

|

ob2 |

Distancing

oneself and breaking any attachment to one’s own exercise to be able to

recognize issues that in a direct or explicit way would not be recognized. |

|

ob3 |

Entering a

critical relationship in an open and plural way, avoiding comparisons typical

of close rivalries. |

|

ob4 |

Discerning and

clarifying the subterfuges and the loopholes we cling to to avoid the creative

trance which a totally new exercise leads us to. |

|

ob5 |

Recognizing the

meaning and the objectivity of an exercise and evaluation parameters that

initially seemed totally ethereal and relative to us. |

|

ob6 |

Assimilating

concepts and questions that are not so easily understandable in an univocal

or direct way. |

|

ob7 |

Assuming the

evaluation criteria of the exercise in an experiential way. |

|

Discussion |

|

|

The discussion

that would fit here is analogous to the one compiled in the ‘collaging the collage’

dynamic. However, this

dynamic goes further: the students not only collect the evaluative content

that the teacher has defined, but also in this case, they are the ones who

develop critical content and later they compare it with the comments of the

rest of the students and the teacher. Thus, we offer

an alternative that delves into the autonomy proposed by the ‘independent

decision making’ line in the work by Bose et al. (2006). However, this

dynamic intensifies certain variables such as play and interaction: ·

At the beginning, the group carries out

the critique, still without knowing the teacher’s opinion, but taking into

account the criteria established in the rubric (first critical milestone). ·

Then, groups have to correctly place the

teacher's comments on each project (second critical milestone, which helps

them to contrast the first step and prepares them for the next one). ·

The groups develop this entire critique,

assessing the work of other colleagues before seeing the comments others have

made about their own work (third critical milestone). As noted in the

‘collaging the collage’ dynamic, this tour allows a distance from one’s own

work, providing time and a process to access critical comments about the

student’s own work that they would not have directly assumed in the first

place. But also, the

milestones described above try to elevate and give direction to mere comments

between students, comments that may lose their critical sense because they

are among ‘equals’. A ‘group peer critique’ (Ibid. p.35) does not guarantee

qualitative judgment just by constituting a group. Groups also deviate,

either to mere condescending comments that do not provide meaningful creative

content, or to the contrary, to destructive criticism generated by pure

rivalry. In this case,

the teacher's intervention, and the dynamic itself try to rescue ‘group peer

critique’ of these deviations. The teacher, through his/her comments and the

design of this dynamic, sets an irrevocable direction. However, while

maintaining all authorship and authority, these dynamic distances the teacher

and also lowers his/her possible authoritarianism, in fact, his/her comments are

exposed and contrasted with those of the students, also generating, by this

interaction, a critical milestone for the teacher hooks (2021). |

|

Figure 5

|

Figure 5 |

Table 5

|

Table 5 Evaluating Koolhaas, ‘anteprojecting’

warming up / Evaluando a Koolhaas, calentando motores anteproyecting |

|

|

Context |

|

|

This dynamic is

carried out before we develop the ‘Anteprojecting’ exercise

defined in the previous article Besa (2019) In this

exercise, the students are going to carry out several preliminary projects in

different commercial premises, rotating a single programme around them: the

programme of a luxury boutique. (The original title ‘Anteproyecting’ has been changed to ‘Anteprojecting’, more apropiate) |

|

|

Procedure |

|

|

p1 |

We put the

tables together and the students’ computers on them, generating a perimeter

tour, so we can move round. |

|

p2 |

On each of the computers,

on the students’ internet browser, we search for a Koolhaas project for PRADA

firm. We offer these projects as inspiring examples for the ‘ante projecting’

exercise that we are going to develop next. |

|

p3 |

In front of

each computer, we place the correction rubric with which the ‘anteprojecting’

exercise will be corrected. |

|

p4 |

Each group uses

a different colour to mark comments on the rubric and corrects Koolhaas’

project using this rubric. |

|

p5 |

We post the

project with our comments and WE MARK KOOLHAAS! |

|

p6 |

We move around

evaluating all the projects and reading the comments of the rest of the

students. |

|

Materials |

|

|

m1 |

Computers connected to the internet. |

|

m2 |

Post-it pads. |

|

m3 |

Printed rubric. |

|

m4 |

Markers or

coloured pencils for each group to mark the rubric with different colours. |

|

Space |

|

|

e1 |

Tables arranged

to form an island that allows a perimeter tour. |

|

Timing |

|

|

10’ |

10 minutes to

place the computers and search the projects on the internet. |

|

40’ |

40 minutes to comment on the projects. |

|

5’ |

5 minutes break. |

|

30’ |

30 minutes to write down the comments. |

|

20’ |

20 minutes to share. |

|

Objectives |

|

|

ob1 |

Reading

(something very unusual nowadays). Reading the rubric and information on the

internet. |

|

ob2 |

Critically

interpreting the information of the internet, helping each other to reach a

common understanding and a shared insight. |

|

ob3 |

Assimilating

the contents and objectives of the exercise by way of a game, avoiding

unsuccessful theoretical classes. |

|

ob4 |

Evaluating one

of the greatest (Koolhaas) by means of our rubric, thus assimilating the

rubric’s contents transversally. At the same time, by joking, we ‘lower’ one

of the greatest from his pedestal. |

|

ob5 |

Breaking our

schemas and stereotypes, contrasting our prejudices with the radicality of

Koolhaas' examples. |

|

ob6 |

Assimilating

previous examples in an active and participatory way, turning research into

experience. |

|

Discussion |

|

|

As the

interactional study model Salama (2015) and the

‘concept-test model’ Ledewit (1985) point out, the

designer approaches a project not so much by an analysis/synthesis process,

but rather in a ‘conjecture/analysis mode’. In the latter, the designer opts

in the first instance for a conceptual scheme that is tested by an analysis

and transformed by analogies into new ideas. That is why the

starting conceptual schemas and previous ideas that build our preconceptions

and conjectures, fundamentally the information, is substantial when

approaching a project Salama (2015), Ledewitz (1985). Therefore,

before the project is carried out, this dynamic enriches the vision of the

students, offering information while, at the same time, providing a tool for

its assimilation (the rubric) Salama (2015). Thus, we offer

information to students not as a set of data that is not significant for the

designer, but rather as information that is assimilated through the

conceptual criteria included in the rubric. We do not offer the students

examples as a catalog of results or standard solutions, neither mere

prototype that are more or less stereotyped; we do not provide unqualified

content, but rather the code of the rubric allows them to assimilate the

information in a projective way. This offers a unique and creative

alternative to the ‘knowledge and design’ approach by Hillier et al. (1972). In this way, we

direct and orient research towards certain conceptual objectives. We do not

discard other orientations that are more open to the students’ proposals,

orientations that promote personal interests of the students, thus guiding

the research towards free and autonomous initiative (as is pointed out in the

work by Fernando, 2018). However, we consider these dynamics more appropriate

for higher courses once the students have acquired and assimilated the

inescapable disciplinary concepts. It is also

necessary to point out that we do not reference Koolhaas in an imitative way,

but rather we investigate his conceptual contributions. Thus, we move away

from the ‘analogical model’ Salama (2015), Simmons (1978). In this way,

as happened in the Aula-Studio exercise proposed in the previous article Besa (2019), we approach references

not so much by copying or imitating them, but rather by conceptually

understanding/interpreting them. In addition,

since we evaluate Koolhaas, we are daring to question one of the greatest. We

dialogue with him through his accomplishments, rotating in a group. As a

result, we overthrow the absolutist and individualistic positions that

certain figures have reached Besa (2019), Besa (2021a). Through an

interactive discussion we break the individualism, the excessive notoriety of

the ‘solo artist’ Kellbaugh (2004). |

|

Figure 6

|

Figure 6 |

Table 6

|

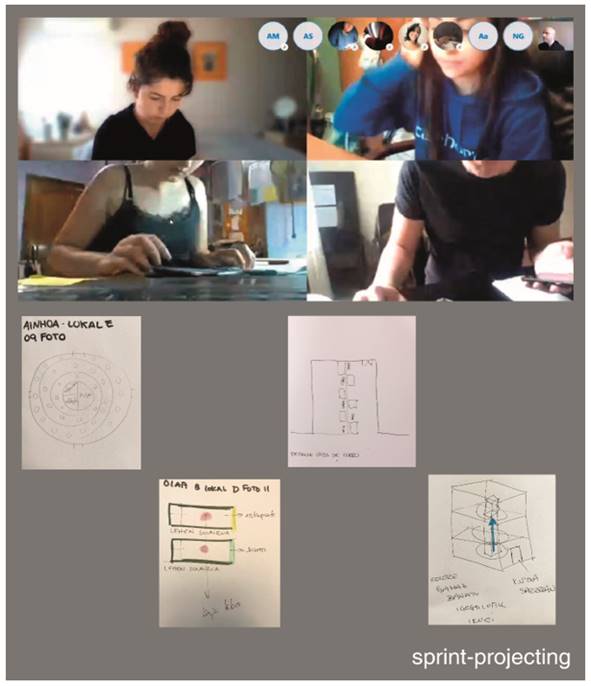

Table 6 sprint-projecting |

|

|

Context |

|

|

This dynamic is

developed in addition to the other dynamics of the 'Anteprojecting' exercise defined in the previous article Besa (2019) |

|

|

|

In the first

instance, we carried out the dynamic of the ‘anteprojecting’ exercise defined

in the previous article: ·

We define an exercise with different

commercial premises: named A, B, C, D, etc. Each with a problem to solve

narrow premises, premises with more than one level, premises in the middle of

a park, premises divided by a commercial passage, premises on the top floor

of a tower, old premises with an entrance shared with the access to other

houses, among other examples. We developed

several two-hour challenges. ·

On the first day, we raffle the different

types of premises among the students, assigning one type to each student.

They have to design a boutique. ·

The next day each student corrects the

design of a partner. They make the correction that the teacher would make,

marking the rubric and marking a copy of the work of the partner (from here

on we continue online due to lockdown). ·

The following day the ‘challenge’

continues: each student reinterprets and redesigns the project that they

corrected the day before. ·

The day after that, together with their

partner, they make a group, and they solve a new project in new premises. Before this

last step, we performed the following dynamic: |

|

Procedure |

|

|

p1 |

Each student

makes an A5 format booklet with several white sheets. |

|

p2 |

We hold a draw;

using Flippity we change the order of the class list. |

|

p3 |

Each student

begins to solve the project in one of the premises. |

|

p4 |

After 5 minutes,

each student passes a picture of his/her work by WhatsApp to the next student

on the list (in the classroom it would be done by physically handing over the

notebook). |

|

p5 |

Each time we

pass the notebook we reduce the time: first 5 minutes, then 2 minutes…

finally 1 minute. |

|

p6 |

Once the

dynamic is over, each student collects all the images that were sent, puts

them in a PDF and delivers the document to the teacher. |

|

Materials |

|

|

m1 |

Due to the

coronavirus lockdown, the dynamics from now on were carried out online. This

is why internet and mobile connection were necessary to send the documents

quickly. |

|

m2 |

White sheets to

make an A5 booklet. |

|

m3 |

Pencil, no

rubber allowed. |

|

Space |

|

|

e1 |

Desk at

student’s workplace. |

|

e2 |

WhatsApp or

email connection network between students. |

|

e3 |

Skype

connection to organize the dynamic, set times, etc. |

|

Timing |

|

|

10’ |

Ten minutes to

explain and organize the dynamic. |

|

40’ |

40 minutes to

develop the dynamic in successive stages of increasingly shorter time. |

|

5’ |

5 minutes

break. |

|

20’ |

Comment on the

result and the objectives of the dynamic. |

|

Objectives |

|

|

ob1 |

Instrumentalizing

representation as a methodological tool, speeding up the representative

process to unsuspected extremes with the intention of reaching what would be

unexpected and impossible solutions in a conventional logical-rational

process. |

|

ob2 |

Liberating

freehand representation with the aim of being able to produce and represent

projects that can be communicated in an agile way without weighing down the

creative process. |

|

ob3 |

Speeding up and

stimulating freehand representation. |

|

ob4 |

Broadening and

expanding students’ own ideas and conceptions through the integration and

transformation of ideas of other colleagues. |

|

ob5 |

Creatively reappropriating

digital and media tools, redirecting them towards unconventional uses

(WhatsApp). |

|

Discussion |

|

|

This dynamic

offers the opportunity to readjust and correct initial sketches and ideas,

enriching the preconceptions of initial approaches by students in the first

instance. Thus, we introduce students into the design method of multiple

cycles: a concept proposal followed by its corresponding critical test that

leads to a new concept Ledewitz (1985). Thanks to these

exchanges, with the reception of the ideas from different colleagues and due

to the constant changes of premises, students obtain a critical distance from

their own project and form their own projecting method. Thus, they assume an

impartial or an indirect criticism that would be difficult to admit directly Ledewitz (1985). |

|

Figure 7

|

Figure 7 |

Table 7

|

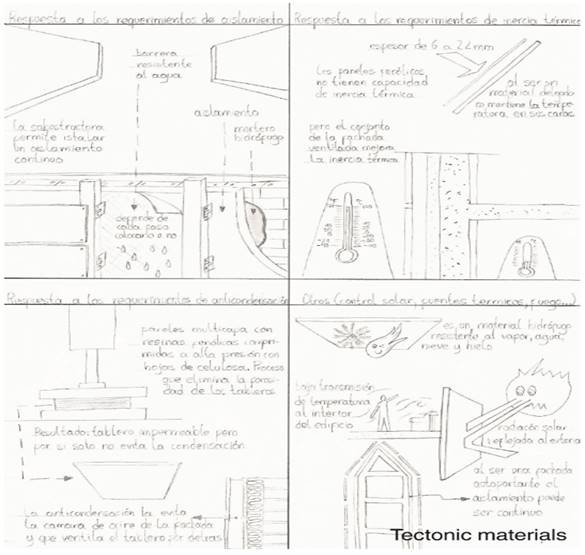

Table 7 Tectonic materials / Materiales

tectónicos / Material tektonikoak |

|

|

Context |

|

|

This dynamic is

carried out before we start the exercise ‘Txiringito’

defined in the previous article Besa (2019). In this exercise,

students must develop a Stand based on a specific construction material. |

|

|

Procedure |

|

|

p1 |

We list some

construction materials: wood, brick, phenolic panel, aluminum composite

panel, plastic, glass, etc. |

|

p2 |

Each of the

materials on the list is linked to each of the published issues of TECTÓNICA magazine.www.tectonica.es/p/pen.html |

|

p3 |

We raffle

materials among the students, assigning a material to each one. |

|

p4 |

We provide a

template with the basic questions to answer: material,

description, variables and types, historical development, landmark buildings,

response to structural stability requirements, self-supporting stability,

permeability, insulation, thermal inertia, condensation, typical details,

typical pathologies. |

|

p5 |

Extending the

theoretical content provided by TECTÓNICA

magazine, students will search for technical and commercial information on

the internet. |

|

P6 |

We proposed the

exercise in line with the subject of construction. The rest of the subjects

of the course also collaborated: history, photography, design culture, among

others. |

|

Materials |

|

|

m1 |

Paper and pencil. |

|

m2 |

TECTÓNICA magazine, each student with the issue

they have been assigned. |

|

m3 |

Mobile device

to photograph or any scanning tool. |

|

Space |

|

|

e1 |

Online space

created with Drive and Skype. |

|

e2 |

This dynamic

was carried out online. If we had physically worked in the classroom, we

would have looked for a way to meet for critical and co-evaluative sessions. |

|

Timing |

|

|

7d |

7 days until a

preliminary deadline in which we evaluate the process by means of written corrections

and common public criticisms via Skype. |

|

7d |

7 more days to

complete the exercise. |

|

14d |

This dynamic

provided time and served as a buffer to organize the online education system. |

|

Objectives |

|

|

ob1 |

Exploring the

ins and outs of the construction discipline, getting used to diving into its

dispersed, generic, and often contradictory information (especially in terms

of terminology and classifying parameters). |

|

ob2 |

Facing the big

problem of the construction world: taking a generic solution from a catalogue

and making it your own solution. Interpreting extensive theoretical

information from specific and particular parameters. |

|

ob3 |

Critically

assuming the commercial information of certain products from defined

technical criteria. |

|

ob4 |

Differentiating

physical construction concepts that due to confusion tend to overlap, all

this through a practical application. |

|

ob5 |

Synthesizing

information visually and graphically. |

|

ob6 |

Liberating

freehand representation in order to be able to produce, and quickly

represent, design sketches and construction details on site. |

|

ob7 |

Defining the

construction bases of the material that has been assigned, as prior

information for carrying out the subsequent project. |

|

Discussion |

|

|

This dynamic is

integrated into a broader exercise, called ‘Txiringito’, explained in the

previous paper Besa (2019). It simulates

a real commission: a construction material company requests to design a

promotional stand in the free space outside the centre where we study. Given the

difficulty of simulating a commission and a real situation in the educational

field, we make this attempt to bring students closer to the ‘case problem

approach’ by Marmot and Symes (1985), in our particular situation, through a

project in our school, which was also going to be completed with an Erasmus

exchange with a school (Alpha College) in the Netherlands. The exchange was

frustrated by the lockdown. However, in

this specific dynamic, the approach to real practice is carried out by

leading students to the commercial world of construction and its disparity of

information. A very real and difficult situation in construction. We tried other

approaches with a fundamentally social content in other courses, close to the

‘case problem approach’ mentioned here. We approached the reality of the

elderly (exercise ‘Ayunta-chunta’ described in the previous paper, ‘#eindakoa#’ (Besa (2019), and

‘Abue-linking’ exercise carried out in the 2018-2019 academic year in

collaboration with Beti Gizartean Foundation). |

|

Figure 8

|

Figure 8 |

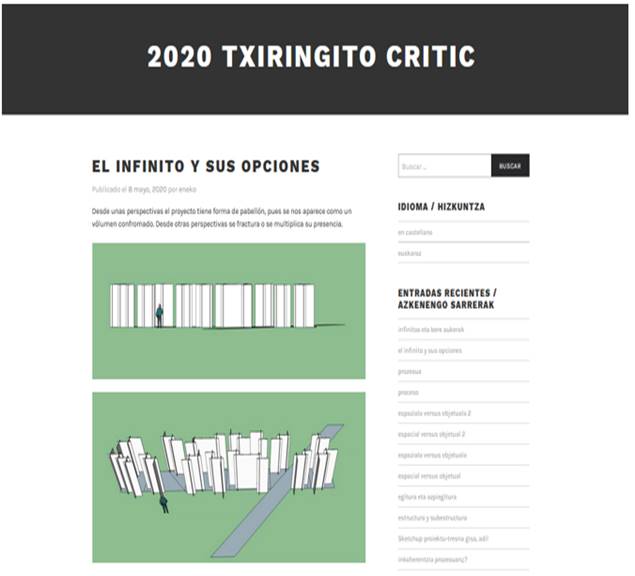

Table 8

|

Context |

|

|

This dynamic is

carried out during the exercise ‘Txiringito’ defined in the previous article Besa (2019). In this

exercise, students must develop a Stand based on

a specific construction material. |

|

|

Procedure |

|

|

p1 |

The teacher

creates a blog using WordPress. An extra blog

produced to deepen the online learning we have been forced into by the

COVID-19 lockdown. |

|

p2 |

Categories are

defined according to language (Basque or Spanish). |

|

p3 |

Teacher creates

posts: ·

images of students’ works ·

images and videos of other projects ·

open comments that need to be completed ·

open controversial issues |

|

p4 |

Students have

to comment on the posts made by the teacher and also any comments made by

other classmates. |

|

p5 |

The teacher

also participates by commenting and promoting discussion and dialogue. |

|

Materials |

|

|

m1 |

Blog created on

WordPress. |

|

m2 |

Drive folder

where the students upload their work. |

|

Space |

|

|

e1 |

Online learning

space created on the web using a blog. |

|

Timing |

|

|

1w |

1 week, the

professor revises the student’s work, he/she posts this work on the blog with

the corresponding comments. |

|

= |

During the same

week, students receive individual critiques; these critiques become group

critiques on the blog. |

|

2w |

The blog

continues active during the following weeks, during a week of vacation and

the weeks after that. It can be accessed by the students, where they can get

some criteria if they are stuck in their project and need to move forward. |

|

1m |

Subsequently,

participation is again encouraged during the following month. |

|

Objectives |

|

|

ob1 |

Evaluating and

co-evaluating one’s own work, in this case on the web. |

|

ob2 |

Obtaining

criteria in the discipline’s issues, a criterion that cannot be achieved

without common and exchanged critiques. |

|

ob3 |

Developing

basic autonomy when making design decisions. |

|

ob4 |

Breaking the

dependency on the critique of the teacher, on the exclusive approval of the

teacher. |

|

Discussion |

|

|

This activity

aims to offer an alternative to the problems of teacher-student criticism

typical of the design studio, problems already mentioned in a previous

dynamic, listed in the work by Ciravoğlu (2014). It should be

noted that the blog changed throughout the course. The first posts were long,

waiting for the comments of the students. Later, this question was improved,

making shorter posts and participating after in the students’ comments. Thus, the blog

evolved, instead of presenting the entire content first while waiting for the

subsequent discussion, it started to clarify the content through

participation in the discussion. In reality,

this dynamic is not so different from previous dynamics and basically it is

the dynamic of so many blogs that already exist. We do not intend to downplay

it, but beyond the originality with respect to the previous proposals, we

show here this dynamic to point out the process of disappropriation that

every teacher must go through. Ellsworth (2005). This is a very

important question, as it is the process that every teacher must follow in

all dynamics. Being a teacher involves a big effort of disappropiation. In

essence, any dynamic should basically ‘make room’ for the initiative and the

will of the students to emerge. Teaching, then, is not “knowing how to

teach”, but rather, “learning to teach”. Teaching to learn by “listening to

the learner”, as the title of the work by Bravo (2019) points out. It is also

important to remember that an online dynamic never replaces a face-to-face

dynamic. At least in this technique, participation is not simultaneous, and

comments are answered with delay, losing direct spontaneity and immediate

interaction. In other techniques and applications tested during the Covid-19

lockdown we have achieved greater fluidity, although it is easily verified

that they never replace actually being present in the classroom. |

|

Figure 9

|

Figure 9 |

Table 9

|

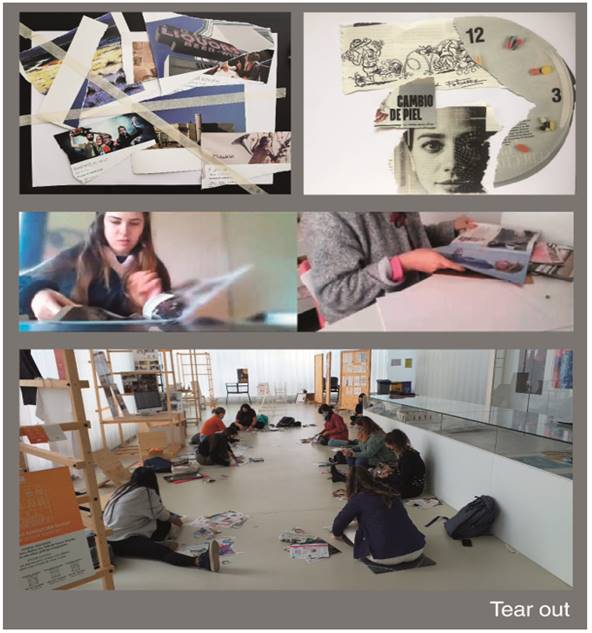

Table 9 Tear out / Rasgar, arrancar / Urratu |

|

|

Context |

|

|

This dynamic is

already mentioned in the previous article Besa (2019), within the ‘Aula-Studio’ teaching unit (pp.

35-37). The exercise comes from the ‘Ideas

Course’ tutored by Amanda Hopkins and Tony Clelford in July 2010 at

Central Saint Martins. |

|

|

Procedure |

|

|

p1 |

First of all,

the teacher explains the dynamic, demonstrating the process by

himself/herself, then the exercise begins: |

|

p2 |

The teacher

asks a question, the students have to answer using the dynamic. How did you

feel during lockdown? What positive attitude

have you found out about yourself that you did not know about before this

period? |

|

p3 |

In a scant

minute, students flip through the magazine and tear out the pages containing

images that suggest something to them in relation to the question asked. Fast,

unconscious, compulsive movements, with hardly any thought, while the teacher

urges them not to stop or not to reflect. |

|

p4 |

Afterwards, in

another minute, students fold (if they want) the pages, selecting the parts

they are interested in, and spread them out over a large space that has been

made available on their desk. Again, compulsive movements. |

|

p5 |

With the mobile

device, each student takes pictures of his/her display of images and uploads

them to Drive. |

|

p6 |

Once the entire

class has performed this procedure, we view and interpret the assignments one

by one. |

|

p7 |

First, around a

single work, anyone other than the author interprets what they see.

Afterwards, the teacher and, later, the author offer their interpretation. |

|

p8 |

The instructions

and the statement of the exercise can be found on the blog, in this case once

the exercise has been completed. |

|

Materials |

|

|

m1 |

A pile of

magazines full of images. |

|

m2 |

Mobile device

to take pictures. |

|

m3 |

In the case of

not having magazines, any material that is available at home can be used. |

|

Space |

|

|

e1 |

It is important

to free up the space to be able to expand on the arrangement of the images.

No spatial limit should further confine our freedom! |

|

e2 |

Space to

comment on images, physically around the table, or webspace due to lockdown.

(The photographs include the Web version and the on-site version performed in

the 2020-2021 academic year) |

|

Timing |

|

|

5’ |

5 minutes to

explain the dynamic. |

|

1’ |

1 minute for a

compulsive and agile tearing out of images from magazines. |

|

1’ |

1 minute to

make an arrangement or display of the chosen images. |

|

10’ |

10 minutes to

comment on each selected display. |

|

20’ |

The dynamic is

repeated once or twice. |

|

15’ |

Reading the

statement and commenting on it (in this case the statement is delivered at

the end, never at the start so as not to condition the exercise). |

|

Objectives |

|

|

ob1 |

Quick and

unconscious movement to enhance the right side of the brain. |

|

ob2 |

Unconsciously

associating or suggesting, but also interpreting the results. |

|

ob3 |

Getting into

creative interpretive subjectivity, different from relativistic opinion. |

|

ob4 |

Exploring the

intrinsic chiasmus type relationship between subject and object

(Merleau-Ponty, 1964) present in all artistic activities (subject/object,

symbolic/formal, etc.) (This objective was already in the paper #eindakoa#). |

|

ob5 |

Integrating a

useful technique for moments of stagnation when it is necessary to encourage

intuition and inspiration. |

|

Discussion |

|

|

This exercise

seeks to offer students a freedom that is typical of creative

self-expression. This is an educational trend developed in the sixties which

echoes approaches of the preliminary course at bauhaus by itten Vega (2019), and even

previous ones, of Fröebel’s or Pestalozzi’s education Vega (2019). However, while

the exercise enhances unconscious expression and projection, it also aims to

introduce students to interpretive work. It is not only about projecting or

expressing, of course it is necessary to allow ideas to flow and to connect

with unconscious strata, but also, it is important to be able to interpret

the result, conceptualize it, decipher the keys that allow us to advance and

glimpse the next step. In this sense,

as we value interpretation as the genuine thought of the project studio, we

share Gallagher’s hermeneutical thought (1992, collected in Philippou (2001). “Based on the two premises of Gallagher’s

exploration of the connection between education and interpretation, that

‘understanding is always interpretational’ and that ‘learning always involves

interpretational’ (Gallagher 1992), I propose a conception of the design

studio as the site of active interpretation, and the site where a synthesis

of a multiplicity of interpretations bearing on architecture takes place. A

hermeneutical approach to the learning activity in the design studio is,

necessarily, based on a conception of the architectural design process itself

as an interpretation process. (…) ‘An essential aspect of all educational

experience (…) involves venturing into the unknown’ (Gallagher 1992). At the

same time, however, ‘a large part of the art of thought, and small enough so

that, in addition to the confusion naturally attending the novel elements,

there shall be luminous spots from which helpful suggestions may spring’

(John Dewey).” |

|

Figure 10

|

Figure 10 |

Table 10

|

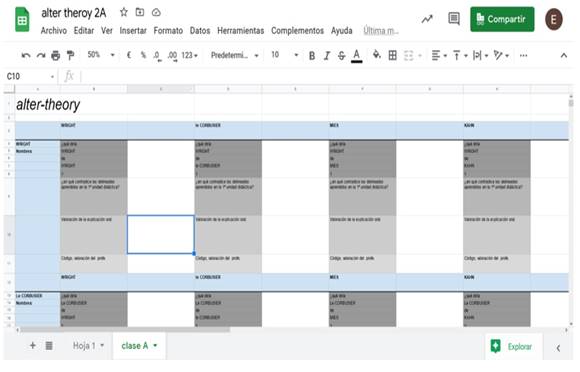

Table 10: Alter-theory |

|

|

Context |

|

|

This exercise was developed in October

2020, once the article had been sent to the magazine of the Spanish version

of the paper. This exercise deserves to be included in the paper since it

introduces an alternative innovation to online teaching, and also because it

complements the previous online exercises. This dynamic

was carried out during the exercise ‘Krisi

dwelling’ defined in the previous article (‘#eindakoa#’, Besa,

2019:37-38). In this exercise, students must graphically analyze mythical

houses of modernity through conceptual drawings without being able to express

anything through writing. |

|

|

Procedure |

|

|

p1 |

Until now, the

teacher used to explain the book ‘Commentary on Drawings by 20 Current

Architects’ Cortés and Moneo (1976). This theory

accompanied one of the didactic units of the course following the traditional

class model. |

|

p2 |

Given the

coronavirus situation, instead of directly transferring the traditional

master class to the online system, we we opte for an alternative: alter-theory. |

|

p3 |

We form groups,

we assign each group one of the architects that the teacher used to explain:

Le Corbusier, Wright, Mies, Kahn, etc. |

|

p4 |

We give out the

material that the teacher used until now. Both the theoretical support and

the slide show. |

|

p5 |

Each group

makes a video, maximum 6 minutes, explaining one of the architects

(exceptionally they can extend it to 10 minutes if the video does not repeat

itself). |

|

p6 |

We upload all

the videos to a shared folder and students watch all the videos. |

|

p7 |

Once students

watch all the videos, they fill in a shared and editable Excel table called

‘alter-theory’. In this Excel table we find the following questions: |

|

p8 |

The first

question in the table (see image): "What

would Le Corbusier think of Wright?" "What

would Wright think of Le Corbusier?" Etc. That is to say,

each group takes on the personality of its architect and makes him comment on

the architecture and drawings of the architect of other groups. |

|

p9 |

The second

question: “How does each

architect contradict what he learned in the previous didactic unit?” Note: In the

previous didactic unit we taught a very precise and very disciplinary way of

delineating. In this didactic unit 'we unlearn what we have learned' and we

discover that drawing and graphic expression are tools that each architect

recreates according to his/her communicative intention and interests (see:

#eindakoa#, Besa, 2019:37-38). |

|

p10 |

In the same

online Excel table, each group makes an assessment of the oral presentation

of the rest of the groups. To do this, we

give the students a list of evaluation criteria for oral presentations. |

|

P11 |

The teacher

makes his/her own evaluations, but places them out of order; students have to

discover which group each teacher’s comment corresponds to. |

|

Materials |

|

|

m1 |

Computer,

internet connection. |

|

m2 |

The book:

‘Commentary on Drawings by 20 Current Architects’ Cortés and Moneo (1976). |

|

m3 |

App or software

for making and editing videos. |

|

Space |

|

|

e1 |

Desk at students’

workplace. |

|

e2 |

Shared folder

on Drive. |

|

e3 |

Shared editable

Excel document. |

|

Timing |

|

|

10’ |

Ten minutes to

explain and organize the dynamic. We explain it using an online video. |

|

2h |

2 hours for

reading the theoretical material and understanding the projects. |

|

2h |

2 hours for the

preparation of the oral presentation and the making of the video. |

|

3h |

3 hours to see

the videos of the rest of the groups and comment on them in the Excel table. |

|

Objectives |

|

|

ob1 |

Transferring

the theory to an online space in a creative way. Encouraging the creation of

another/alternative theory, alter-theory. |

|

ob2 |

Recreating

theory in a personalized, active, and involved way. |

|

ob3 |

Bringing the

theory back to life, leading the students to even take on the role of the

‘big’ giants that we explained in this theory. |

|

ob4 |

Relating and

linking the characters that until now have been shown to us as free-standing

heroes in representations that distort their human figures. That is why it is

a theory of ‘the other’, of ‘the alter’, a theory of otherness, alter-theory. |

|

ob5 |

Integrating the

evaluation criteria in an experiential way, seeing errors similar to mine in

‘the others’ (alter-theory) and allowing ‘the others’ to make me see mine. |

|

ob6 |

Participating

in a cross evaluation in which even the teacher's evaluations are exposed to

criticism. |

|

Discussion |

|

|

I teach in two groups, in which: Group B: total failure. Group A: relatively

well resolved, although we can observe some of the same problems as Group B.

(Group B had the handicap of being fewer, therefore there was more work. In

addition, in their case, they had to translate all the material into Basque). With the implementation

of this dynamic, in the event that the students manage to minimally express

the concepts related to the drawing of ‘the great’ architects, we can see how

innumerable interactions and fruitful interpretations arise from the

questions asked in the table. On the one hand, the students take on the role

of the architects deducing and recreating the opinion that they would offer

each other about their drawings. On the other hand, the perception that the

students capture with respect to the drawings of 'the greats' in relation to

what they previously learned in the previous didactic unit is tremendously

interesting. Actually, the

dynamic worked in both groups. Even in the crudest failure, it also worked.

In fact, when the teacher saw the videos, he immediately foresaw the failure,

yet he still went ahead and let the students crash. What interest

could we have in this failure? ·

Suffering in my own flesh how badly I

sometimes communicate, having to fill in a table based on the information

that was poorly communicated by other colleagues. Suffering in my

own flesh ‘the others’ to find out

who I am. Alter-theory. Using cross

dynamics in which I simply evaluate colleagues is not enough, they tend to

lead us to soft generic judgments because we all avoid conflict in one way or

another. In this dynamic, we are all compromised because if the partner has

not done his/her job correctly I cannot continue with mine. ·

Loss of information. Some students

did not heed the teacher’s instructions and did not carry out this task in

pursuit of the established objectives. Some students

made their video from other material, different from the one prescribed in

the exercise. This material did not even refer to the architects’ drawings,

nor did it answer the questions that students had to fill in on the table. Although the

instructions were provided in a short video that the students could watch

over and over again, and despite the fact that all the material was presented

clearly in a folder, the basic instructions of the teacher were disregarded. Furthermore,

when we have to transmit the information ourselves, we lose content, as the

failure of the exercise shows. In other words,

the failure of this dynamic makes us aware of the emptiness we are doomed to

if we do not assume autonomy and basic responsibility. ·

We note the difficulty of some texts like

these. We do not access the basic depth, nor do we have the basic culture or

basic knowledge to understand them. We are facing a vicious circle, because

in order to understand this type of text it is necessary to read them more,

but to be able to read them with some interest it is necessary to understand

them. In other words,

failure leads us to better appreciate the explanations of those who can

introduce us to understandings that we cannot access by ourselves. Failure

leads us to appreciate something that until now we had taken for granted. Thus, surely

this dynamic does not reach the depths of someone like Lévinas, who (in his

work Totalité et infinite, 1961)

attempts to open sameness to radical otherness

(to radical difference), however,

it is a dynamic that has made us break ourselves and be aware of how we

became very accustomed to the ‘same’

without giving it the value that corresponds to it. But precisely,

if this game calls into question how little we take advantage of a

traditional theoretical class, its failure also reveals the loss of

information and rigor that occurs in many alternative dynamics. This failure

has led the students to request a repetition of the exercise to collect the

information that had been lost. Something completely new that we have to

fully appreciate. The student’s

performance in the following exercise improved substantially. |

|

2. CONCLUSION

This paper presents an open conclusion. It does not end like the previous one (#eindakoa#), in which the last part wrapped up the paper with an explanation of the cohesion and meaning of the entire course.

On the contrary, in this case, the conclusion stays open to a continuity and prolongation of these essays in works and dynamics in the near future. In fact, the Covid-19 lockdown has truncated the normal development of the course and has forced us at the last moment to implement dynamics in an online format, which shows to what extent this article is open to contingency.

However, we do not understand this contingency as something negative, nor is that the only reason for not concluding this paper in the same way as the previous one. The true reason is that the work is in a moment of experimentation that has a lot to do with the same experimental character of these dynamics (thus we share Ellsworth's approach, (2005). This does not mean that a conclusion has been avoided, since in some way it is already present in the discussion and evaluation of each one of the dynamics.

Beyond the fact that the article is open to future conclusions, we do find a conclusive common point to all the dynamics: the experimental and artistic, almost performative, nature of this approach. Since, if the objective is teaching to design, if the content of the course consists of teaching how to create actions and even events, its dynamics cannot but be artistically designed and also be thought of as pure actions and events.

In this way, the article is open to development and action, to future situations that, creatively addressed, will yield pedagogical alternatives from which we will continue to learn.

Credits

The works shown in this article, as well as on the blog, were developed by students of Interior Design Projects course who took part in these dynamics, during 2019-2020 and 2020-2021:

Amaia Alba, Yaiza Etxaniz, Janire Ezcurdia, Naroa González, Naiara Guerra, Nerea Labraza, Iraia Lecuona, Selma Dennis Linares, Amaia Molinuevo, Maite Morrás, Andoni Muñóz, Alisson Nicol Ochoa, Ainhoa Saavedra, Jorge Leonardo Velázquez, Julene Arburua, Jakue Arruabarrena, Olatz Barragan, Marina Bocos, Andrea del Hoyo, Jasna Gora de Vicente, Naroa Iraola, Sarai Iturriotz, Maider Ann Jenkin, Eider Macazaga, Ainhoa Mardones, Yeray Marquez, Rocio Ortega, Naia Ortiz de Zarate, Amaia Pidal, Naiara Armentia, Naia Campesino, Clara Gibaja, Maialen Muñoa, Ane Rayo, Amaiur Sáez de Eguilaz, Josune Santiago, Nerea Sanz, Amaia Subinas, Eire Vila, Katalin Ortiz, Ane Anton, Ainare Azconizaga, Maiane Eguiluz, Marta Escudero, Paula Fernández, Maitane Fernández del Moral, Delia Gómez, Aitana Manzano, Patricia Marquinez, Anne Miranda, Gaizka Perez de Carrasco, Nahia Pombar, Sara Rodríguez, Yuqian Shi, Emilia Tit, Garazi Zúñiga.

In order to develop the comparative of the ‘Collaging the collage’ dynamic, we also used works by the students in 2018-2019:

Iñigo Artaraz, Ane de la Fuente, Itzea Díaz, Josune Espada, Edurne Fuente, Rubén García, Osoitz González, Naiara Guerra, Jone Hernández, Tamara Herrera, Maialen Lekue, Cristina Llarena, Irune López de Zubiria, Aroa Martínez, Leire Soler, Mikel Azkoiti, Estera Mardarie, Miren Montilla, Ainhoa Mugica, Nerea Olagüenaga, Izaskun Ortega, Haizea Polo, Olatz Razquin, Garazi Remacha, Yuriko Shinto, Ane Trinidad, Jorge Valle.

The works published in the dynamic called ‘Tear out’ were carried out by Jorge Leonardo Velázquez (on the left) and by Amaia Molinuevo (on the right).

The work that can be seen in the screenshot taken from ‘Txiringito critic’ and the work in ‘Tectonic Materials’ were developed by Jorge Leonardo Velázquez.

The works published in the dynamic called ‘Collaging the collage’ were carried out by Nerea Olaguenaga (on the left) and by Amaia Alba (on the right).

The works published in the ‘Sprint-projecting’ dynamic were carried out by (from left to right): Ainhoa Mardones, Olatz Barragan, Nerea Labraza and Andrea del Hoyo.

Photographs by the author, except:

Small photographs of the ‘Collageando el collage’ dynamic. Top right (orange post-it), photograph by Naia Campesino. Bottom left (colored post-it), photograph by Emilia Tit

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Anthony, K.H. (1987). Private Reactions to Public Criticism; Students, Faculty, and Practicing Architects State Their Views on Design Juries in Architectural Education. Journal of Architectural Education, 40(3), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1080/10464883.1987.10758454

Besa, E. (2015). Arquitecto, obra y método. Análisis comparado de diferentes

estrategias metodológicas singulares de la creación arquitectónica

contemporánea. Tesis Doctoral, ETSAM UPM. Text of the conclusion and the index

in English published here:

https://idus.us.es/handle/11441/70078?locale-attribute=en.

Besa, E. (2019). #eindakoa# (lo que hemos hecho) Un MÉTODO pedagógico del MÉTODO de Proyectos de Diseño de Interior. EARI, Educación Artística Revista de Investigación, (10), 33-63. This paper (#eindakoa#) has been presented, peer reviewed and accepted to be published in English in the Architectural Episodes 02 congress proceedings. https://doi.org/10.7203/eari.10.13763

Besa, E. (2021a). Arquitecto, obra y método : Kazuyo Sejima, Frank O. Gehry, Álvaro Siza, Rem Koolhaas, Peter Zumthor. Diseño Editorial.

Besa, E. (2021b). dynamics-aktion. Propuesta de dinámicas pedagógicas, útiles en el Taller de Proyectos de diseño y más allá. EARI, Educación Artística Revista de Investigación, (12), 23-42. https://doi.org/10.7203/eari.12.17633

Bose, M., Pennypacker, E. & Yahner, T. (2006). Enhancing critical thinking through 'independent decision-making' in the studio. Open House international, 31(3), 33-42. https://doi.org/10.1108/OHI-03-2006-B0005

Bravo, J.A.F. (2019). La sonrisa del conocimiento. Una metodología que escucha al que aprende para hablar al que enseña. Editorial CCS.

Ciravoğlu, A. (2014). Notes on architectural education : An experimental approach to design studio. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, (152), 7-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.09.146

Cole, R. J. (1980). Teaching Experiments Integrating Theory and Design. Journal of Architectural Education, 34(2), 10-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10464883.1980.10758644

Cortés, J. A. & Moneo, R. (1976). Comentario sobre dibujos de 20 arquitectos actuales. Escuela Técnica Superior de Barcelona.

Dutton, T.A. (1987). Design and Studio Pedagogy. Journal of Architectural Education, 41(1), 16-25. https://doi.org/10.2307/1424904

Ellsworth, E. (2005). Places of Learning. Media, Architecture, Pedagogy. RoutledgeFalmer. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203020920

Fernando, N.A. (2007). Decision Making in Design Studios : Old Dilemmas and New Strategies. In SALAMA, A.N. and Wilkinson, N., (Eds), Design studio pedagogy : horizons for the future. The Urban International Press, 143-152.

Frederickson, M.P. (1990). Design juries : A study in lines of communication. Journal of Architectural Education, 43(2), 22-27. https://doi.org/10.2307/1425031

Freud, S. (1991). Tótem y tabú y otras obras (1913-1914) VIII. (J. L. Echeverry, Trad.) Amorrortu editors. (Original work published 1913-1914).

Friedman, K. (2003). Theory construction in design research : criteria: approaches, and methods. Design Studies, 24(6), 507-522.

Hillier, B., Musgrove, J. & O'Sullivan, P. (1972). Knowledge and design. En MITCHELL, W. (ed.), Environmental design : Research and Practice. University of California at Los Angeles.

Kellbaugh, D. (2004). Seven fallacies in architectural culture. Journal of Architectural Education, 58(1), 66-68. https://doi.org/10.1162/1046488041578167

Ledewitz, S. (1985). Models of Design in Studio Teaching. Journal of Architectural Education, 38(2), 2-8. https://doi.org/10.1080/10464883.1985.10758354

Levinas, E. (1977). Totalidad e infinito. Ensayo sobre la exterioridad. (M. García Baró (Trad.) Ediciones Sígueme. (Original work published 1961).

Marmot, A. & Symes, M. (1985). The Social Context of Design : A Case Problem Approach. Journal of Architectural Education, 38(4), 27-31. https://doi.org/10.2307/1424860

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1964). Le visible et l'invisible. Editions Gallimard.

Ochsner, J.K. (2000). Behind the Mask : A Psychoanalytic Perspective on Interaction in the Design Studio. Journal of Architectural Education, 53(4), 27-31. https://doi.org/10.1162/104648800564608

Philippou, S. (2001). On a Paradox in Design Studio Teaching or the Centrality of the Periphery. In Proceedings of Architectural Educators : Responding to Change At: Architectural Education Exchange, Centre for Education in the Built Environment (CEBE), Cardiff University.

Robinson, J. W. & Weeks, J. S. (1983). Programming as a Design. Journal of Architectural Education, 37(2), 194-206.

Salama, A. M. (2015). Spatial Design Education. New Directions for Pedagogy in Architecture and Beyond. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315610276

Schön, D.A. (1984). The architectural Studio as an Exemplar of Education for Reflection-in-Action. Journal of Architectural Education, 38(1), 2-9. https://doi.org/10.1080/10464883.1984.10758345

Simmons, G. (1978). Analogy in design : Studio teaching models. Journal of Architectural Education, 31(3), 18-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10464883.1978.10758137

Vega, E. (2019). De Weimar a Ulm. Mito y realidad de la Bauhaus 1919-1972. Experimenta Editorial.

[1] This paper has been partially published in Spanish in

this previous version:

Besa, E.

(2021b).

dynamics-aktion. Propuesta de dinámicas pedagógicas, útiles en el

Taller de Proyectos de diseño y más allá. EARI, Educación Artística Revista de Investigación, 12, 23-42.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7203/eari.12.17633