ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

READING SILAPPADIKARAM IN THE CONTEMPORARY TIMES: A STUDY OF ITS PERFORMATIVE ASPECTS

Dr. Venkata Naresh Burla 1![]()

![]() ,

Dr. M. Ramakrishnan 2

,

Dr. M. Ramakrishnan 2![]()

![]()

1 Assistant Professor, Department of

Performing Arts, Central University of Jharkhand, Ranchi, Jharkhand, India

2 Assistant

Professor of Folklore, Department of Anthropology and Tribal Studies, Central

University of Jharkhand, Ranchi, Jharkhand, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

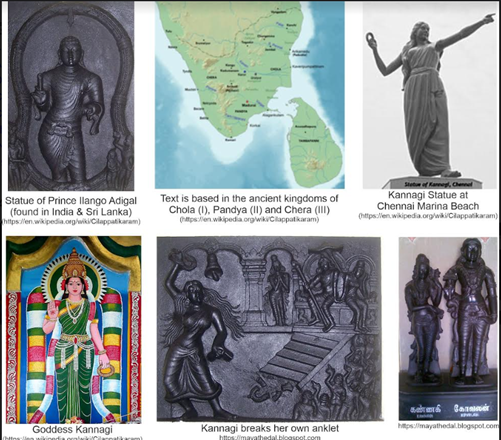

Silappadikaram is a classic literary work of ancient Tamil society, believed to

have been composed around the 5th century BCE by Ilango Adigal.

It encompasses elements of Jainism, Buddhism, and other religious traditions

then prevalent, and also it incorporates themes,

myths, and theological principles from each of the belief systems. The epic

offers a vivid portrayal of both virtuous and malevolent deeds, while

exploring themes of joy and suffering. What sets Silappadikaram apart from other epics is that the text focuses on an ordinary

couple, as opposed to kings and armies. The text painstakingly demonstrates

the behavioural nuances of society, ranging from

commoners to rulers. Love and separation, gaining and losing power, are

recurring themes in Indian classical dramas by notable playwrights like Vishakadatta, Kalidas, Bhasa,

and Bhavabhuti, etc. These plays were created with the intention of

influencing society, specifically targeting individuals in positions of power

and authority. However, post-colonial Indian theatre took a different

approach, placing common individuals as protagonists in the plays. Works such

as Aadhe Adhure, Ghashiram Kotwal, Hayavadana, and Sakharam Binder address prevalent societal issues, with the central character

being an ordinary person. The main aspects of modern theatre and the plays

mentioned here primarily explore the everyday activities of common

individuals and how they are influenced by other members of society, economic

factors, and politics. This paper studies the contemporary relevance of Silappadikaram in modern theatre by drawing a comparison with these modern

Indian plays. |

|||

|

Received 20 February 2024 Accepted 28 March 2024 Published 06 April 2024 Corresponding Author Dr.

Venkata Naresh Burla, burla.venkatanaresh@gmail.com

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v5.i1.2024.992 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2024 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Silappadikaram, Modern

Theatre, Identity, Sexuality, Politics |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Silappadikaram (the tale of an

anklet) is one of the most important works of

classical Tamil literature, composed by Ilanko Adikal in the 5th or 6th century

CE, which is considered the Sangam period of Tamil literature Parthasarathy (2004/1993).

The epic

poem is believed to have been written in the city of Madurai, which was a center of Tamil culture and literature at that time. The

name Silappadikaram means "the story of

the anklet" in Tamil, referring to the incident that triggers the main

events of the poem. It is a narrative poem that tells the story of Kannagi, a

virtuous woman who seeks justice for her husband Kovalan's wrongful execution.

The epic is divided into three parts: the Puhar, the Madurai, and the Vanchi

episodes. Silappadikaram serves as a

valuable source for understanding the social and cultural history of ancient Tamil

Nadu by providing a vivid portrayal of the customs, traditions, values, and challenges.In the epic, the rigid

social hierarchies prevalent in ancient Tamil Nadu are depicted, including the

division of society into different castes and the norms and customs associated

with them. It highlights the challenges faced by individuals who navigate these

hierarchies, such as Kannagi's struggle for justice despite her social status.

The text offers glimpses into the roles and expectations of women in ancient

Tamil society. Kannagi exemplifies the idealized virtues of a devoted wife, but

she also demonstrates resilience and agency in seeking justice for the death of

her husband. Silappadikaram provides insights

into trade, commerce, and agrarian practices in ancient Tamil Nadu. A narrative

follows Kovalan, a merchant, and emphasizes the importance of trade routes and

markets to the economy of the region. There are various cultural practices depicted

in the epic, including dance, music, and religious rituals, shedding light on

the cultural fabric of ancient Tamil society. As an example, the Madurai

Meenakshi Temple and its festivities play a prominent role in the narrative,

reflecting the importance of religious institutions in people's lives. However,

this paper aims to discuss the importance of the text in the modern context,

specifically within the framework of performing arts, encompassing both folk

and modern theatrical forms. The paper explores the theatrical quality of the

text and the performative elements found within, highlighting their

significance in addressing contemporary questions pertaining to the performing

arts. Moreover, this paper exemplifies an interdisciplinary approach to

classical Tamil text that resonates profoundly in today's multifaceted world of

artistic expression and cultural inquiry.

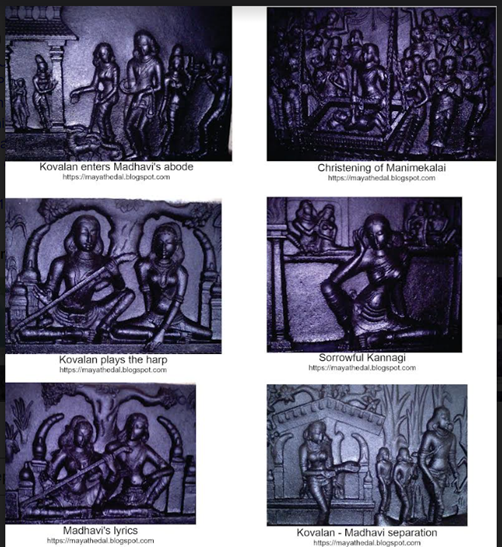

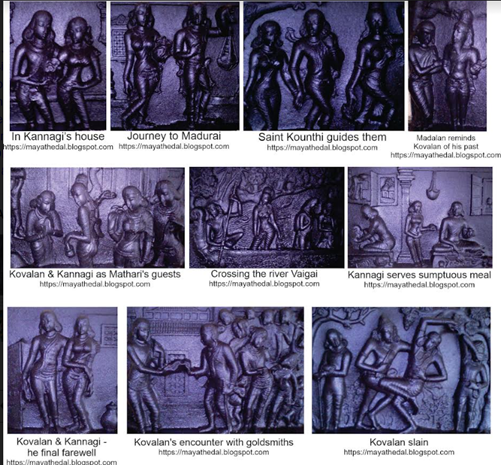

Silappadikaram explores a

wide range of themes, encompassing love, loyalty, justice, and fate. The

central theme of the epic revolves around the pursuit of justice. The narrative

follows the story of Kovalan, a young merchant, and his union with the virtuous

Kannagi. Despite his love for the courtesan Madhavi, Kovalan's life takes a

tragic turn when he is falsely accused of theft by a deceitful goldsmith. The

goldsmith, who had stolen the queen's anklet, accuses

Kovalan and convinces the king of Madurai to execute him. In a turn of events,

Kannagi arrives in Maturai as a widow and proves

Kovalan's innocence. Filled with grief and anger, she tears off one of her

breasts and hurls it towards the burning city of Maduri. Kannagi's pursuit of

justice ultimately leads to the downfall of the king and the city itself. An important

underlying theme in Silappadikaram is the

power of fate. The poem highlights the belief that human actions are influenced

by destiny and that even the most virtuous individuals can face misfortune.

However, it also suggests that righteous actions can alleviate the impact of

fate and eventually lead to redemption.

Silappadikaram holds the

significance as a Tamil literary work and serves as a valuable resource for

comprehending the culture, society, and history of ancient Tamil Nadu. Notably,

the poem provides a captivating portrayal of gender roles and relationships. It

presents a nuanced perspective on the position of women in ancient Tamil

society, depicting them as active and independent individuals rather than

passive dependents under male guardianship. Kannagi, the poem's female

protagonist, emerges as a resilient and fearless woman who ardently fights for

justice, ultimately toppling a corrupt king. In contrast, Kovalan is portrayed

as impulsive and reckless, driven by his pursuit of pleasure and wealth.

Moreover, Silappadikaram offers insights into

the intricate social hierarchies prevalent in ancient Tamil society. It

showcases a diverse range of social classes, from commoners to royalty,

illuminating how individuals navigate their positions within these hierarchies.

For instance, Kovalan, being a prosperous merchant, utilizes his wealth and

influence to curry favor

with the ruling elite. Conversely, Kannagi, a commoner, employs her intellect

and strength to challenge the corrupt king and bring about justice.

The poem also grants glimpses into the religious and

cultural practices of ancient Tamil society. It underscores the central role of

religion and spirituality in the lives of ordinary people, highlighting their

efforts to forge a connection with the divine in their daily existence.

Furthermore, Silappadikaram underscores the

significance of art and literature in ancient Tamil society, showcasing how

these expressive forms were employed to convey moral messages and reflect the

prevailing values of the era. In addition to its rich socio-political and

economic elements, Silappadikaram holds

historical importance as one of the world's oldest surviving epic poems. It

provides a detailed account of the Pandyan, Chera,

and Chola dynasties that once flourished in ancient Tamil Nadu. That is, all

the three ancient Tamil kingdoms have been found mentioned in the narrative

text not merely as casual reference but intertwined with the story - story

begins from Poompukar, the capital of the Cholas,

then it moves towards Madurai and ends in the land of Cheras

land. The division of the text itself is seen as evidence for it that while Puharkkandam (Puhar Chapter) mentions the events that

happened in the city of Puhar that falls under the Chola kingdom, Maduraikkanadam (Madurai Chapter) portrays the events that

happened in the city of Madurain in the Pandya

kingdom and Vanchikkandam (Vanchi chapter) presents

the events that happen in the Chera kingdom. Subramanyam (1977), Noble (1990), Dikshitar (1978), Dikshitar (1939), Kapoor (2023). However, this

study primarily focuses on the performance perspective of the poem, seeking to

delve into its performative aspects and implications.

2. Themes and

Significance of Silappadikaram

Love, separation, and the acquisition or loss of power are

recurring themes in Indian classical dramas, shared by playwrights such as

Kalidasa, Bhasa, Bhavabhuti, and Shudraka,

among others. These themes serve as narrative devices to explore the human

condition and portray the challenges and struggles individuals face in their

personal and public lives. Silappadikaram,

being a significant narrative with meticulous descriptions and the

incorporation of narrative formulas, exemplifies the principles of narratology

found in modern literature. It recounts the simple yet elegant romantic

dynamics among the married couple Kovalan and Kannagi, as well as Madhavi, a

renowned dancer, and the daughter of Chitrapathy, who

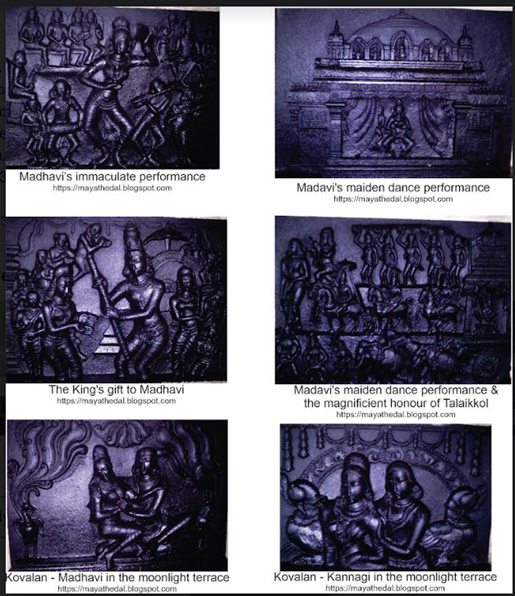

becomes Kovalan's mistress. When viewing the story from a performance

perspective, Madhavi emerges as a prominent character. She is a talented dancer

who began her training at the age of five and achieved mastery by the age of

twelve. Madhavi's performance at the annual festival in Kaveripoompattinam

signifies the importance of such festivals, stage performances, and prize

distributions (where she received a Royal Medal and 1008 grams of coins), among

other elements. Kovalan falls in love with Madhavi after witnessing her

captivating performance at the annual festival, which is depicted in

contemporary popular culture such as cinema and theatrical performances.

Silappadikaram holds

importance as it offers theories on the origin of dance. The talaikkol used in Madhavi's performance symbolizes

Jayanta, the son of Indra, and is a significant element of her debut public

performance, known as Arangetram (staging of first performance). The misdeeds

of Jayanta, who was cursed by sage Agastya along with celestial nymph Urvasi,

become part of the curse's ritualistic symbolism and are also incorporated into

worship practices. Silappadikaram mentions

numerous dance forms within its text, including Alliyam,

Kodukotti, Kudaj,

Kudam, Pedi, Kadayam,

Pandarangam, Mal, Tudi, Marakkal, and

Pavai. Many of these dance forms are

associated with gods and deities such as Shiva, Muruga, Kama, Durga, Krishna,

Lakshmi, and Indrani. The first six dances are performed in a standing

position: Alliyam depicts Lord Krishna's

triumph over a mad elephant, Kodukotti portrays

Lord Shiva's dance after destroying the triple cities of demons, Kudaj represents Lord Skanda's victory over demons, Kudayam is performed by Kannan after securing the

release of his grandson Anirudh from Banasura's prison, Pandarangam

illustrates Shiva's dance to entertain Brahma following his victory over the

demons' triple cities, and Mal describes the wrestling match between

Bana and Lord Krishna. The remaining five dances are performed in a lying

position: Thudi depicts Skanda's dance after

defeating the demon Suran, Kadayam portrays

Indrani's dance at the north gate of Banasura's palace, Pedu showcases

Manmathan's dance in the guise of a eunuch to secure the release of his son

Anirudh, Marakkal represents Goddess Durga's

dance with stilts when facing poisonous creatures sent by demons, and Pavai depicts Goddess Lakshmi's dance against warring

demons. Silappadikaram also makes several

references to performance-related terms such as natya (dance), ranga (stage), pindi (body

movements), varam (tune), karanam (dance sequences), and mandala

(circular formation). It is believed that that some of the dance principles

from Natyashastra were adapted for Tamil settings, as evident from the dance

terminology used in Silappadikaram. The text

also presents three types of dancers that can be compared to modern-day

classifications: kaval ganika (women guards), kalattiladumkutti (dancers in the military camp),

and adalkuttis (dancers who perform ahakkuttu or sringara

dances like padams). In this context, Kapila

Vatsyayan notes that "It appears that by the time of the Silappadikaram, the three-fold classification of

dancing girls as ganikas, kuttis,

and adalsiladi—corresponding to the later

classifications taliyilar, patiyilar,

and devaradiyal—had come into vogue" Vatsyayan (1968), 213-214.

The section on Arangetram holds

importance within the text and provides detailed coverage of various elements

such as Madhavi's dance teacher's proficiency and skills, accompanists such as

singers and musicians, and crucially, stage management details. Silappadikaram mentions two distinct types of dances

based on akam and puram: Ahakuttu and Purakkuttu, respectively. Akam comprises twin concepts such as Vasai (satire) and Pugal (praise), Vettiyal

(performed before kings) and Poduviyal

(performed before ordinary people), Vari and Vari Shanti, Shanti and Vinodham, and Aryam. Shanti Kutthu is further divided into Chokkam

or Suddha nrttam

(pure dance, later known as nritta) and

incorporates the 108 karanas. Mei Kutthu, on the other hand, encompasses Desi, Vadugu, and Singalam.

PurakKutthu has three modes: Perunatai, Charyay, and Bhramari.

The inclusion of various Kutthus in Silappadikaram indicates its significance as a

text that reflects modern performance types. Furthermore, the beauty of the

text lies in Aranketrukkathai, which presents its

content in the blended mode of Iyal (prose), Isai

(music), and Natakam (drama), collectively

known as Muttamil (three forms of Tamil

language). Scholars have recognized parallels between Tamil and Sanskrit

traditions on this level. Kutthu is extensively

detailed in the text, with kravi kutthu and aaichiyar

kutthu being discussed in depth. Dance forms like

kodukotti and pandarangam

are regarded as sacred to Shiva, Tudi to Murugan, Marakal

to Kottravai, Pavai to Lakshmi, and Kadayam to

Indrani. Dance varieties such as Marakkal, Pavaikootu, and Kodukotti remain

popular till date, for example, kudamadal (Karagattam) and marakkaladal

(dummy horse dance). These dances are now classified as folk arts Vatsyayan (1968), 213-214.

Interestingly, the description of dances and koottu

is not limited to Arankettrakkathai alone; other

sections of the text mention dances performed by hunters, cowherds, and tribal

communities. Vettuvavari, popularly known as the

dance form of hunters, is depicted as Salini, born into the Maravar

clan, beginning her dance with appropriate gestures, and becoming possessed by

divinity, with her hair standing on end and hands raised aloft. She continued

to dance, moving from place to place, astonishing the foresters... she then

proclaimed these unfulfilled vows Vatsyayan (1968), 213-214.

3. Indian plays -

popular Themes

The theme of love held a central position in the plays

written by playwrights like Kalidasa, Bhavabhuri, and

Bhasa, etc. Love was often portrayed as a

transformative force capable of uniting individuals, but also capable of

driving them apart. Kalidasa's play "Shakuntala" exemplifies

this theme, with the love story between King Dushyant and the hermit Shakuntala

taking centre stage. The play illustrates how love can transcend social

barriers and bring together people from different backgrounds. However, it also

emphasizes the repercussions of forgetting love and underscores the

significance of memory and remembrance in relationships. In Bhavabhuti's play

"Uttararamacharita," the

departure of Sita from Ayodhya serves as a pivotal event that leads to the

ultimate conflict between Rama and Ravana. The play delves into the emotional

turmoil experienced by Sita as she leaves her home and is compelled to adapt to

a new life in the forest. The theme of gaining or losing power emerges as

another prominent motif in classical Indian dramas. These plays often portray

the struggles individuals face when attempting to acquire or retain power,

along with the ensuing consequences. Bhasa's play

"Charudatta"

exemplifies this theme, featuring a central character who is a poor Brahmin.

After saving the life of a courtesan, he attains power and wealth. However, his

newfound authority comes at a cost, as he becomes the target of jealousy and

deceit from those around him. These themes serve to explore the human condition

and depict the challenges and struggles individuals encounter in their personal

and public lives.

In addition to Sanskrit Kavya (poetry) and literary

texts from the time of Natyashastra, Silapathikaram

stands out for providing concrete evidence of a solo dancer and her art. The

poem portrays either the female protagonist or antagonist as accomplished and

trained dancers, indicating a period in which dance forms thrived. It

demonstrates the existence of patrons who supported and safeguarded the arts as

well as the artists themselves. This reflects a progressive dimension of

society that allowed women to pursue dance as a profession and showcased their

talents on public platforms. For the dance theorist and historian Mandakranta

Bose, the dance was indeed an evolving art as evident in textual references.

And for him, the dramatists and authors such as Kalidasa, Vararuci,

Bhavabhuti, Harsha, Rajasekhara, Damodara Gupta, Jayanta Bhatta, and Alamkarikas such as Dandin, Bhamaha,

Bhoja, Sharadatanaya, Sagaranandin,

etc., have used numerous terms to denote dances that utilize body movements for

the expression of ideas and emotions, and that are absent in Bharata's work -

indicating their subsequent developments, suggesting an expansion of the art of

dancing Mandakranta (2002).

The Indian theatre scene has always served as an active

arena for social commentary and cultural critique. The plays written and staged

in India during the late 20th century marked a significant shift as common

individuals became the protagonists, and societal issues took centre stage.

Four plays that captured the imagination of both audiences and critics were

"Aadhe Adhure”

(Halfway House), "Ghashiram Kotwal” (Ghashiram, the chief police officer), “Hayavadana”

(Horse face/Horse headed), and "Sakharam Binder" (Sakharam, the

Binder). The rationale behind selecting "Aadhe Adhure,” "Ghashiram

Kotwal," "Hayavadana," and

"Sakharam Binder" in relation to the text lies in their thematic

depth and cultural significance. Each of these plays offers a profound

exploration of human psychology and confronts the prevalent social and cultural

challenges of their respective times. "Aadhe Adhure" delves into the complexities of familial

relationships and societal expectations; "Ghashiram

Kotwal" critiques power dynamics and corruption; "Hayavadana"

explores the intricacies of identity and desire; and "Sakharam

Binder" addresses issues of gender and personal autonomy. By analyzing these plays, the text aims to provide a

comprehensive understanding of the intersection between dramatic literature,

psychological inquiry, and socio-cultural commentary, thereby enriching the

discourse on these themes within the context of the chosen text. Each of these

plays delved into the complexities of the human psyche and delved deeply into

the social and cultural challenges of their respective times.

4. Aadhe

Adhure: The Quest for Completeness

"Aadhe Adhure,"

written by Rakesh (1999), is a notable

example of a realistic modernist play. The play delves into the lives of a

middle-class family, exploring their struggles with unfulfilled aspirations,

insecurities, morality, societal norms, individual freedom, and internal

conflicts within the family unit. The protagonist, Savitri, is an ordinary

woman and mother of three who possesses a good education and puts in immense

effort but fails to provide her family with a respectable standard of living.

Dissatisfied with her life, she desperately seeks solutions to her problems,

resorting to dubious business practices, socializing with wealthy men, and

manipulating her boss to secure a job and stability for her unemployed son.

Savitri strives to balance her work and home life while enduring an abusive and

unemployed husband. Despite her relentless efforts to improve the family's

lifestyle and social status, she faces constant disappointment. Within the

family, Savitri confronts conflicts, including with her husband Mahinder. Her

son Ashok rejects the support of her boss to enter the workforce due to his

disdain for him. He spends his time flipping through magazines and randomly

tearing out images of figures like Marilyn Monroe and Audrey Hepburn. Savitri's

elder daughter Benny had left home years ago and returns to find her marriage

in turmoil. Her younger, more rebellious daughter Kinni displays precociousness

and disobedience, preoccupied with exploring adult relationships. In the play,

nearly every character is engaged in conflict with one another. After years of

coexistence, the family reaches a point where they find themselves unable to

live with or without one another Saraswat (2014). In the play,

the character Savitri experiences a deep dissatisfaction with her life and

yearns for a sense of fulfillment. "Aadhe Adhure" delves into

themes of loneliness, disillusionment, and existential angst, which were

relatively new in Indian theatre during its time. The play examines the

intricate relationships and conflicts among family members as they grapple with

finding their own identities and pursuing happiness. The confined living space

and financial struggles further intensify their tensions, resulting in

explosive arguments and bitter confrontations. Through the characters'

struggles and conflicts, the play raises poignant questions about societal

expectations, gender roles, and the true meaning of happiness and fulfillment in life. The play concludes with an open-ended

ending, allowing the audience to interpret the characters' destinies and

reflect upon the thought-provoking issues presented throughout the play.

5. Hayavadana:

A Search for Identity and desire for fulfillment

The play “Hayavadana" (lit.

horse-headed) written by Girish Karnad in 1971, holds a significant place in

modern Indian literature as it delves into themes of identity, love, and

desire. Set in medieval India, the play revolves around the story of two best

friends, Devadatta and Kapila, who both develop feelings for the same woman,

Padmini, who serves as the protagonist. The power dynamics among these three

main characters serve as a crucial aspect of the play. Devadatta, a Brahmin,

possesses linguistic and poetic skills, and holds a position of power and

privilege in society. Kapila, on the other hand, is a wrestler, strong

physically but belonging to a lower caste, and lacks the same privileges as

Devadatta. Despite being married to Devadatta, Padmini becomes the object of

affection for both men, leading to a competition for her love and attention.

Padmini, caught in the middle, struggles to make a decision

for herself Karnad

(1997)."Hayavadana" offers a unique blend of myth, folktales,

and contemporary Indian society, tackling themes such as identity, love, and

the quest for fulfillment. The play also delves into

the power dynamics between men and women within society. Padmini, despite being

a strong and independent woman, finds herself constrained by the societal

expectations and limitations imposed upon women in ancient India. She is

expected to be submissive and obedient to men, without the agency to make her

own decisions. This places her in a challenging position as she navigates her

own desires and emotions while also grappling with societal norms. Another

prominent aspect of "Hayavadana" is its

exploration of the concept of identity. The play raises questions about whether

identity is determined solely by physical appearance or if it is shaped by

inner qualities such as intelligence and kindness. It also probes the influence

of social status on one's sense of self-worth. The search for completeness

emerges as another vital theme within the play. Each character embarks on a

personal quest for something that they believe will bring them a sense of

wholeness—be it love, intelligence, or physical perfection. However, they

ultimately come to realize that true completeness can only be attained through

self-acceptance, recognizing that external factors cannot provide lasting fulfillment.

6. Ghashiram

Kotwal: The Abuse of Power and the Corrupt Nature of Politics

The play "Ghashiram

Kotwal," (police chief Ghasiram) written by

Vijay Tendulkar in 1972, is set in 18th-century Pune and revolves around the

story of Ghashiram, a man who ascends to power as the

kotwal (police chief) of the city. However, his corrupt and ruthless methods of

maintaining order ultimately lead to his downfall.The

drama begins by introducing the morally corrupt state of the Brahmins in Pune,

who hold positions of power. The dishonest chief of Pune, Nana Phadnavis,

visits the lavani dancer Gulabi,

where Ghashiram is employed Balsing

(2019). Ghashiram's

intellect impresses Nana. The next day, as a Brahmin, Ghashiram

attends the Peshwa's feast to collect alms. However, he faces mistreatment, is

falsely accused of pickpocketing, and is sentenced to prison by the Pune

Brahmins. This incident fuels Ghashiram's desire for

revenge. To accomplish his objective and secure the position of Kotwal from

Nana, Ghashiram trades his own teenage daughter,

Gauri. Once appointed, he enforces strict regulations on the city,

indiscriminately imprisoning individuals for minor offences. Nana turns a blind

eye to the grievances of the commoners who complain about Ghashiram,

as he is deeply infatuated with Gauri. As the situation escalates, the Brahmins

ultimately lodge a complaint with the Peshwa. The Peshwa summons Nana, who

orders Ghashiram to be killed Tendulkar (2014). The play's

protagonist, Ghashiram, undergoes a transformation

from an ordinary man to a powerful figure in society. He offers his daughter

Gauri to Nana Phadanvis in exchange for the position

of Kotwal, utilizing the corrupt system to his advantage. The play delves into

themes of power, politics, and the exploitation of power. It offers a critical

portrayal of the Peshwa regime, highlighting how the ruling class manipulates

and exploits ordinary individuals for their own gain."Ghashiram

Kotwal" serves as a potent critique of power abuse and the corrupt nature

of politics. Ghashiram's rise to the position of

kotwal is not based on merit, but rather on his willingness to engage in any

means necessary to achieve his ambitions. He resorts to bribery, blackmail, and

even murder to climb the social ladder, prioritizing his own interests over the

welfare of the people he is entrusted to serve. From its onset, the play

establishes a power dynamic between the Brahmins and non-Brahmins in Pune. Ghashiram initially faces suspicion and is treated as an outsider

by the Brahmins. However, as he gains power and influence, he exploits his

position and manipulates the system to his advantage. He employs his authority

to eliminate adversaries and solidify his position, resorting even to the

murder of a woman who rejects his advances. As Ghashiram

becomes increasingly corrupt, the play delves into the conflict between

individual desires and societal norms. Ghashiram's

insatiable thirst for power and wealth drives him to commit progressively

heinous acts, which he justifies as necessary for maintaining order in the

city. The play juxtaposes his actions with those of other characters who

attempt to resist the oppressive power structure of Pune. Nana Phadnavis, for

example, confronts Ghashiram and suffers the

consequences for challenging him. Throughout the play, Tendulkar emphasizes the

role of social and political hierarchies in perpetuating corruption and

injustice. Ghashiram's actions receive support and

protection from influential figures in the city who turn a blind eye to his

crimes as long as he serves their interests. Moreover,

the play highlights the gendered aspect of power dynamics, as Ghashiram's actions are facilitated by the subjugation of

women and the objectification of their bodies. Tendulkar (2009)

7. Sakharam

Binder: An Exploration of sexuality, power, and patriarchy

"Sakharam Binder,"(Sakharam,

the Binder) the play written by Vijay Tendulkar in 1972, delves into the themes

of power, gender, and morality. The play narrates the story of Sakharam Binder,

a bookbinder who resides outside the confines of societal norms, engaging in

sexual relationships with multiple women. However, his unconventional lifestyle

leads to conflict and violence, ultimately resulting in his own downfall.

Sakharam introduces himself as an individual who has rejected traditional roles

and societal norms, striving to live life on his own terms Wadikar (2011). Sakharam's rejection

of societal norms is most evident in his relationships with women. He holds the

belief that marriage is a social construct that restricts individuals, and

instead, he seeks women who are willing to cohabit with him and fulfil his desires

without the need for marriage. Additionally, he advocates for women to break

free from the confines of traditional gender roles imposed by Indian society

and encourages their freedom of expression. Tendulkar portrays Sakharam

Binder's character issues, which predominantly revolve around violence. These

conflicts arise from interpersonal and personal relationships, vividly

reflecting the characters' tendency towards violent expressions throughout the

play. The central theme of the play revolves around the relationship between

the protagonist, Sakharam, and his seventh and eighth mistresses, Laxmi and Champa. These three characters hold pivotal roles

in the narrative, shaping its entirety. Dawood, Sakharam Binder's Muslim

friend, is a secondary character in the play, initially portrayed as composed

during the first act. However, his deceitful nature becomes evident later on as he engages in a relationship with Champa,

Sakharam's eighth mistress, betraying his friendship with Sakharam Binder.

Faujdar Shinde, Champa's husband, is similarly depicted as a violent individual

who subjects his wife to abuse while under the influence of alcohol. The play

concludes with Sakharam's downfall, as the women he has taken in depart from

his life, and the repercussions of his violent past catch up to him. These

characters are portrayed as individuals prone to various forms of violence,

including physical, psychological, political, sexual, and verbal violence Sharma

(2019).

Through the character of Sakharam, Tendulkar illuminates

the significance of power in relationships and its potential to oppress and

exploit others. The women in the play bear the brunt of Sakharam's whims and

desires, underscoring the power dynamics embedded in their interactions. The

play exposes the pervasive violence and exploitation endured by women in the

name of tradition and societal norms. Moreover, it prompts to question the

responsibility of individuals in perpetuating these oppressive systems and

emphasizes the necessity for resistance and rebellion against them. The play

engenders crucial inquiries regarding the essence of human relationships and

the intricate nature of power dynamics, abuse, and gender roles within Indian

society. It challenges conventional patriarchal norms and underscores the

urgency for a more nuanced comprehension of human relationships. Silappadikaram shares common themes with "Aadhe Adhure," "Hayavadana," "Ghashiram

Kotwal," and "Sakharam Binder." These works collectively delve

into the complexities of human relationships, the repercussions of one's

actions, and the quest for fulfillment and identity. Mohan

Rakesh's play "Aadhe Adhure"

explores themes of marital discord and societal expectations. It portrays the

struggles of a middle-class Indian family and the conflicts that arise from the

husband's inability to provide for his family. Similarly, Silappadikaram

also addresses marital discord and societal expectations, depicting Kovalan's

abandonment of his wife Kannagi due to his pursuit of wealth and material

pleasures. Girish Karnad's play "Hayavadana"

delves into themes of identity and the human search for completeness. It

narrates the story of Devadatta and Kapila, two friends who both love the same

woman, Padmini. Kapila becomes consumed by his desire for Padmini and

sacrifices his own identity in a desperate attempt to win her love. Similarly, Silappadikaram portrays Kovalan as being consumed by

his desire for wealth and material pleasures, leading to his tragic downfall.

Vijay Tendulkar's play "Ghashiram Kotwal"

explores themes of political corruption and power struggles in 19th-century

India. It narrates the story of Ghasiram, a corrupt

municipal official who ascends to power through deceit and manipulation.

Similarly, Silappadikaram addresses themes of

justice and power struggles through Kannagi's quest for justice following her

husband Kovalan's wrongful execution. In "Sakharam Binder," another

play by Vijay Tendulkar, themes of gender roles and societal expectations are

examined. The play portrays Sakharam, a bookbinder who takes in and mistreats

women abandoned by their families. Similarly, Silappadikaram

presents Kannagi as a strong and independent woman who challenges societal

expectations and norms. Overall, these works collectively explore universal

themes of human relationships, consequences of actions, and the search for

completeness and identity, albeit through different cultural and historical

contexts.

8. Conclusion

In general, Silappadikaram

is a profound and intricate work that provides a captivating insight into the

social and cultural norms prevalent in ancient Tamil society. By depicting

gender roles, social hierarchies, and religious and cultural practices, the

epic poem offers a nuanced and enlightening perspective on the values and

beliefs of that era. It delves into significant topics such as feminism,

women's empowerment, social justice, human rights, and cultural identity. Silappadikaram stands as a crucial cultural and

literary artefact, extensively studied in the field of performance studies, and

revered by scholars and readers alike for its enduring significance. It is treated as

a pure literary text that is devoid of any political context or activities

constructed around the politics of the kingdoms in a direct way. However, it

subtly deals with the socio-cultural and political life that can be seen from

Kannagi’s reaction and the Madurai king’s response in admitting the blunder he

committed. "Am I the king? I listened to the words of a goldsmith! / I

alone am the Thief! Through mu error / I have failed to protect the people / Of

the southern kingdom. Let my life crumble in the dust. / He fell

down in a swoon. His great queen / Shuddered in confusion,

and said: / There is no refuge / For a woman who lost her husband.” /

(The Silappadikaram: the Tale of Anklet, tr. Parthasarathy

(2004/1993): 189-190, quoted in Kapoor

(2023):167-168). Then, "When the lord of the Vaigai saw

the dust on her body, / Her dark hair undone, the single anklet / Blazing in

her hand, he lost heart. / Her words Pounded his ears, and he gave his life.” /

(The Silappadikaram: the Tale of Anklet, tr. Parthasarathy

(2004/1993): 190, quoted in Kapoor

(2023):168). The fair and

impartial judgement is being upheld through these lines and the whole text is

configured to prove this point, and the kings of those time had been sensitive

to well-being of the people through their moral and ethical life. It is presented

in three books (kandams), further

divided into stories (kathairs), with each kandam named after the location where the story

takes place, such as Punarkkandam, Maduraikkandam, and Vanchikkandam.

The text comprises twenty-five stories and five song cycles: The love songs of

the seaside grove; The song and dance of the hunters; he round

dance of the herdswomen; The round dance of the hill dwellers; and The

benediction. The inclusion of patikam,

although considered a later addition, holds significance not only for this text

but also for other literary works. It signifies the poetic intent to elucidate

certain truths, such as the consequences faced by even kings if they violate

the law and the commendation of the virtuous wife by great men. It also

underscores the manifestation and fulfillment of

deeds. The poem is named Cilappatikāram, the

epic of the anklet, as the anklet symbolizes the illumination of these truths Adigal (1992), 21.

Although the text is considered parallel to Sanskrit

literature, it contains mentions and references to numerous Sanskrit epics,

legends, and puranic texts. In this regard, Zvelebil's

statement is relevant, as he describes Silappadikaram

as the "first literary expression and the first ripe fruit of the

Aryan-Dravidian synthesis in Tamilnadu" Rani

& Shivkumar (2011), 79-99. Silappadikaram holds a significant place in popular

culture, with film adaptations based on its content. Additionally, it has

attained spiritual and religious significance among the people, with Kannagi

being deified and worshipped in many parts of South India. However, the text

possesses contextual relevance from a performance standpoint, necessitating an

in-depth exploration of its contemporary relevance in folk and modern theatre.

This discussion aims to initiate further exploration in this direction.

In addition to its rich intertextuality with Sanskrit

literature and its enduring cultural and religious significance, the

performative aspects of Silappadikaram warrant

further examination to fully appreciate its contemporary relevance. The text's

narrative complexity and dramatic elements suggest its potential for adaptation

and reinterpretation in various forms of theatre, both traditional and modern.

By delving into its performative dimensions, scholars and artists can uncover

new layers of meaning and relevance that resonate with contemporary audiences.

Exploring how Silappadikaram is enacted and

experienced on stage can provide valuable insights into its enduring appeal and

relevance in today's cultural landscape. Therefore, while acknowledging its

historical and literary importance, it is crucial to expand our analysis to

encompass its performative aspects, thus paving the way for a deeper

understanding of its continuing impact and significance in both scholarly

discourse and popular culture. Another point that needs to be mentioned about

the text is that though it introduces Madhavi as a central character who had

been trained rigorously in music, dance, and the poem composition, through the

reflection of social attitudes on the artist, the text introduces the twist in

the story. Therefore, Kovalan’s movement towards Madhavi is not accidental

rather it is the narrativization of social attitude towards arts and artists.

However, the text constructs and projects Madhavi not as an ordinary woman

performer, but as a morally upright woman who proves her moral and ethical

character by returning all the wealth of Kovalan stolen by her mother without

the knowledge of either Kovalan or Madhavi.

Finally, to the credit of the text apart from the performative elements, it is considered as a secular text when compared to other contemporary texts such as Manimeghalai, Civaka Chinthamani and Vilaiyapathi. Further, the moral or justice the text establishes through the neat description of the story is relevant in the modern context, for instance, “Arasiyal pizhaithorku aramkootru avathum” that reads as for those who have committed injustice in ruling/politics, it is believed that the justice itself will turn as demon of death. Kapoor (2023), 166.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Adigal, I. (1992). The Cilappatikāram of Ilanko Adikal: An Epic of South India. New York: Columbia University Press.

Balsing, A. M. (2019). Vijay Tendulkar's Ghashiram Kotwal: As A Revenge Tragedy. Literary Endeavour 10 (1), 23-26.

Dikshitar, V.R.R. (1939). The Silappadikaram. Humphrey Milford: Oxford University Press.

Dikshitar, V.R.R. (1978). The Cilappadikaram. Madras: South India Shaiva Sidhanta Publications Society.

Kapoor, R. (2023). The Concept of Justice and Dharma in Cilappathikaram: the Story of Anklet, Vol.-24, 160 -170.

Karnad, G. (1997). Hayavadana. Oxford.

Mandakranta, B. (2002). Speaking of Dance: The Indian Critique, (New vistas in Indian Performing Arts, No. 3) D.K. Print 2. World.

Noble, S. A. (1990). The Tamil Story of the Anklet: Classical and Contemporary Tellings of"Cilappatikaram". Diss. University of Chicago.

Parthasarathy, R. (2004/1993). The Cilappatikaram: The Tale of an Anklet. Penguin India.

Rakesh, M. (1999). Highway House: A Translation of Ashe Adhure. Worldview Publication.

Rani, P., & Shivkumar, V. (2011). "An Epic as a Socio-Political Pamphlet". Portes, 5(9), 79-99.

Saraswat, S. (2014). The Quest of Completeness: Mohan Rakesh's Aadhe Adhure. Asian Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, 2(9), 86-88.

Sharma, P. (2019). Delineation of Domestic Violence: A Study of Vijay Tendulkar's Shakaram Binder. Journal of Advanced and Scholarly Research in Allied Education, 16(1), 394-397.

Subramanyam, K. N. (1977). The Anklet Story: Shilappadhikaaram at Ilango Adigal. Delhi: AgamPrakasan.

Tendulkar, V. (2009). Ghashiram Kotwal. Seagull Books.

Tendulkar, V. (2014). Five Plays. Oxford University Press.

Vatsyayan, K. (1968). Classical Indian Dance in Literature and the Arts, Sangeet Natak Akademi.

Wadikar, S. B. (2011). Sakharam Binder: Tendulkar's Human Zoo. The Criterion: An International Journal in English 2(1), 1-12.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.