ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Depiction of Hindu Iconography in the paintings of Thota Vaikuntam

Banti Kumar 1![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Waseem Mushtaq 2

,

Dr. Waseem Mushtaq 2![]()

![]()

1 Research

Scholar, Department of Fine Arts, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, Inida

2 Associate

Professor, Department of Fine Arts, Women’s College, Aligarh Muslim University,

Aligarh, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The history of

a human being is also the history of who or why or how human beings have

worshipped something that they believed was more powerful than them. The

history of human being is also the history of

artists as how they have imagined, depicted or visualized this superpower.

For instance, in the Indus Valley Civilization, we find that humans made clay

idols which may have been worshipped, for instance, in the form of Mother Goddess

and Pashupati Nath. Across prehistoric, ancient and medieval periods, as the

circumstances of human life changed, so did the nature of worshiping and the

nature of art. This act of worship gave rise to some of the greatest

religions in the world with their dedicated sacred text, rituals, followers,

and patronage. Each religion had a distinct and unique equation with art and it was based on this equation that it became

possible to study and interpret a work of art. This approach of study or

interpretation was later classified as iconography. The present paper aims to

locate the presence of Hindu iconography in modern India with special

reference to the paintings of Thota Vaikuntam, who

is known for drawing extensively from the iconographic representations of

Shiva, Ganesh, and Krishna. |

|||

|

Received 22 February 2024 Accepted 04 June 2024 Published 15 June 2024 Corresponding Author Banti

Kumar, drbantikumarsingh@gmail.com

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v5.i1.2024.981 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2024 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Hindu Iconography, Hindu Art, Thota Vaikuntam, Modern Indian Art |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

In Hinduism, the imagery of Vishnu, Shiva and Devi constitutes the primary visual imagery. Gods and goddesses are worshipped as a concrete image (murti) made, generally, in stone, terracotta, plaster, ivory, and metal ("Hindu iconography" 2021). Over the millennia of its development, Hinduism has adopted several iconic symbols, forming a major part of Hindu iconography, that are imbued with spiritual meaning based on either the scriptures or cultural traditions. The exact significance accorded to any of the icons varies with region, period, patronization and denomination of the followers. Over time, some of the symbols, for instance, the Swastika, have broader association while others like Aum are recognized as unique representations of Hinduism ("Indian Iconography and sculptural art" 2021). Other aspects of Hindu iconography are, for example, the terms murti for icons and mudra for gestures and positions of the hands and body.

An icon, derived from the Greek word

"eikon," refers to a representation of a God or Saint in a painting,

mosaic, or sculpture that is intended for worship or is related to religious

rites. While it shares some similarities with primitive fetishist signs used in

simple rituals, it holds a clearer and more sophisticated meaning. This Greek

term "eikon" finds its close counterparts in Indian terminologies

like area, beta, and vigraha, which also refer to

representations of deities or saints receiving the adoration of their bhaktas

or worshipers. In some Indian works of literature, these icons are described as

the actual bodies or forms (Tanu or Rupa) of the gods. Most often, these

depictions are anthropomorphic

or theomorphic, but they can

also take the form of symbolic representations with no clear shape. Iconography

is a specialized discipline that concerns itself with the study of these

religious images. Banerjea (1956), p. 1.

In the

realm of religious iconography, icons or images of religious figures and symbols

hold importance in worship and religious rituals. These icons carry specific

meanings and convey theological concepts to believers. Additionally,

iconography encompasses the process of creating sacred images and the artistic

techniques and conventions employed in their production.

The

Hindu iconography is largely anthropomorphic, which implies the depiction of

Gods and goddesses in humanized forms. For example, the artists depiction of

ten heads of a human to represent Ravana, symbolizes that Ravana’s mind was as

powerful as the mind of ten humans. In Indian art there are examples of

enormous scale of the statutes of Gods and goddesses made in

order to demonstrate the superiority of God. In Hindu idols, each idol

has two, four, six and sometimes eight hands. And in each hand, there is a

different symbol or instrument or gesture denoting various meanings (Achar). Everything connected with the Hindu

icon has a symbolic meaning; the posture, gestures, ornaments, number of arms,

weapons, vehicle, consorts and associate deities (parivāra

devatā). The symbolism or the iconic imagery has

its origin in various sacred texts such as Brāhmanas

and Aranyakas, and later the iconic symbols are

explained in the various Purāṇas such as Srimad Bhāgavatam, Viṣṇu Purāṇa,

Śiva Purāṇa; Upaṇiṣads

such as Gopāla-uttara-tāpini Upaniṣad, Kṛṣṇa

Upaniṣad and Āgamas

and so on.

The research

paper focuses on the paintings of Thota Vaikuntam who

predominantly draws from Hindu iconography. The objective of employing such

references is to convey ancient cultural aspects to contemporary society and to

fulfill the purpose of Hindu iconography through the artist's work. Many modern

Indian artists have incorporated, depicted or appropriated Hindu iconography

into their artworks. Of the several reasons, the one that appears most common

is that, by means of re-visiting iconographic themes the artists want to

reconnect with the values that they hold to be significantly relevant to the

contemporary society and reclaim as a perennial way of life. Investing each

symbol and sign with a sense of profundity the artist brings the ancient Indian

aura of divinity and spirituality back to life through these paintings. Some of

the most recurrent examples of iconographic representation that Vaikuntam has extensively explored are, for instance,

Krishna with a flute; Krishna shown lifting the Govardhan Mountain to protect

Vrindavan's villagers, birds, and animals from Indra's wrath; Radha and Krishna

and so on.

2. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

In this

research paper, the researcher aims to explore and analyze scripts and

artifacts that shed light on the fundamental dimensions of art, particularly

focusing on the unexplored aspects within Hindu iconography. To achieve this,

the researcher extensively examines relevant literature and thoroughly

investigates the icons and symbols present in the artist's work concerning

Hindu iconography. The study involves a comprehensive review of books written

by prominent authors who specialize in Hindu iconography, along with a thorough

analysis of the artist's body of work. Through this examination, the researcher

uncovers confidential information pertaining to previously unexplored areas

within the realm of iconography.

The research

methodology relies on secondary data and draws from various sources, including

books, journals, research papers, and artworks. By utilizing descriptive

research methods, the paper documents and observes the multiple transformations

in art forms facilitated by the influence of Hindu iconography.

Overall, this

research paper delves into the lesser-explored dimensions of art and

iconography by drawing from a wide array of data sources and using a

descriptive approach to comprehensively understand the changes brought about by

Hindu iconography in the realm of art.

3. OBJECTIVE

The focus of

the present study is to trace and investigate the impact of Hindu iconography

on modern art in India with specific reference to the works of Thota Vaikuntham.

By examining the influence of Hindu iconography on modern artists, the research

aims to shed light on how this rich traditional practice of the past has

inspired and shaped artistic expressions in the present.

By closely

examining contemporary artworks, the research seeks to identify how artists

have adapted, appropriated and reinterpreted traditional iconography to suit

modern sensibilities and societal contexts.

The research

also focuses on understanding the transformative changes that Hindu iconography

has brought to different art forms over time. By studying the evolution of

artistic styles, techniques, and themes, the study aims to reveal the dynamic

relationship between Hindu symbols and icons and their influence on the visual

arts.

In essence,

this study endeavors to present a comprehensive and detailed exploration of how

Hindu iconography has left an indelible mark on the artistic landscape of

India, from ancient times to contemporary art scenes. By tracing this influence

and delving into the nuanced connections between icons, symbols, and art forms,

the research provides valuable insights into the cultural and artistic heritage

and its continuing relevance in the contemporary art.

4. LITERATURE

REVIEW

Many

scholars hold the view that image worship was part of the Vedic culture, though

there are many contrary views as well. One of the most cited book

in the context of Hindu iconography is Elements of Hindu Iconography, 1912 by

Gopinath Rao, (1872-1919), Indian archeologist and

epigraphist. Gopinath Rao for instance, affirms that image worship in India to

be a very ancient tradition citing examples from the period of Yaksa and Ptanjali. As mentioned by Ratan Parimoo,

‘Ptanjali had defined dharana as the process of fixing the mind on some object, well

defined in space, while Panini (around sixth century B.C.) had explained the

meaning of pratikrti

as “anything made after an original”’ Parimoo (2023): 19. As mentioned by Parimoo that Rao was clear in his methodological approach

by ‘listing postures of deities and ayudhas including their symbolism before describing the

deities based on references from Silpa

texts as well as Puranic myths. Rao’s contribution in the field of Hindu

iconography, especially his scholarship on Saivism and Saiva iconography, will

form the basic framework in identifying and classifying the knowledge of Hindu

iconography with respect to traditional Indian art. The classical scholarship

on Hindu iconography will further guide in identifying, assessing and analyzing its impact on modern Indian art in general and in

the artwork of select modern Indian artists in particular.

The

references that Parimoo is hinting at are very

crucial in developing a basic understanding as how Hindu iconography was

formulated to interpret the ancient and classical art of India. For instance, Parimoo recounts that:

“Rao had incorporated

Coomaraswamy’s paper on Dance of Siva (1911) in his section on nrtya-murtis, the latter had acknowledged in

a paper of 1920s that Gopinath Rao had quite rightly affirmed that the

so-called Trimurti of Elephanta caves was essentially

a Saivite image known by the nomenclature, Sdasiva or

Mhadeva, citing references concerning the five heads

and corresponding five powers attributed to Siva. He identified further Saivite

images under this classification. He also discovered textual sources for the

eight-headed images of Siva. This section paved the way for Stella Kramrich’s paper on Siva Mahadeva at Elephanta

(1946) and with the readymade textual sources available, enabled her to create

an integrated prose, interweaving form and content.

Parimoo further cautions about the

possibility of prejudices and biases that the implication of iconography can

lead to, as he cites the views asserted by J.N. Banarjea, Indian historian and

Indologist, in his book The Development of Indian Iconography, 1941:

The term ‘icon’ (icon, Gr.

Eikon), figure representing a deity, or a saint, in painting, mosaic and

sculpture, which is in some way or the other associated with the rituals

connected with the worship of different divinities.

Banerjee’s

understanding of Hindu iconography, however, is limited in the sense that he

perceived iconography as subservient to religion. His accounts on iconography

also suffered due to his prejudiced response to pre-historic and tribal artists

for treating them as fetishistic and crude. It is

important to refer to and take into account all shades

of scholarship in order to fully understand the significance of Hindu

iconography and its relevance to modern Indian art.

In

the western art history, the contribution of Erwin Panofsky is considered

paramount in the development of iconography as a branch of study that deals

with “exploration and interpretation of the subject-matter in a work of art”. The term iconography has its origin in the

Greek words where ‘eikon, means “image” and graphe,

means “writing”. In this way iconography implies “the way in which an artist “writes” the image, as well as what the

image itself “writes”—that is, the story”. Taking into

account both the approaches as applied by Rao and Panofsky, we can

conveniently overcome the limited and prejudiced approach of the likes of

Banerjee.

Panofsky formulated three broad methods of iconography: description,

analysis and contextualized interpretation of the art object.

As a

comparative method, iconography will attempt to explore, analyse and interpret

the content or subject matter of the artworks in a specific context, that is,

to locate the impact or influence or presence of Hindu iconography in the

selected paintings of modern Indian artists.

Further, Panofsky realized that iconography is limited as it

is traditionally concerned with religious content, and thus, in

an attempt to expand its scope, he introduced the term “iconology.” Iconology, according to

Panofsky, not only expands the scope of ‘iconography’ beyond religious content

but also includes all possible aspects that would “illuminate the content of a

work of art”. The progression from “iconography studies” to “iconology”

emphasizes the fact that mere “identification”, “authentication” or even

“stylistic analysis”, attributes of “iconography studies”, was not enough to

grasp the holistic understanding of a work of art, hence a more rigorous

approach is required to not only study the content of an artwork but also the

contextual circumstances and temporal environment, historical purpose, cultural

significance, political dynamics and so on.

In

this way, methodologically, the present study will apply both ‘iconographic’

and ‘iconological’ approaches. ‘Iconographic’ approach will address the

traditional/classical Indian art in the light of Hindu iconography with

reference to the textual scholarship and visual sources. ‘Iconological’

approach will explore, analyze and contextually

interpret, using qualitative interpretation, the selected art works in the

light of the impact of tradition on Indian modernism.

The

works of some of the prominent scholars that will play a crucial role in

identifying and exploring various dimensions of Hindu iconography are: Bhattacharya, B.C. The Jaina Iconography, Chandra,

Pramod, On the Study of Indian Art, Coomaraswamy, A.K. ‘The Origin of the

Buddha Image’, Eck, Diana L., Darśan: Seeing the

Divine Image in India, Flood, Gavin, An Introduction to Hinduism, Huntington,

Susan, The Art of Ancient India, Sivaramamurti, C.

Sanskrit Literature and Art: Mirror of Indian Culture, Memoirs of the

Archaeological Survey of India.

Many

modern and contemporary Indian artists have drawn inspiration from various

aspects of Hinduism. Some inspirations are direct while some are subtle or

metaphorical. The present paper may not be able to incorporate all such

artworks. However, the artists who have been consistently drawing inspiration

from Hinduism and whose works reflect a sustained aesthetic and conceptual

engagement with Hindu iconography will find a mention here. There is a great

possibility that not many artworks, that bear an explicit impact of Hindu

iconography, will have been a subject of some serious research. This would

imply that many relevant art works have hardly been approached with an academic

investigation in the form of books, articles, curatorial exhibitions and so on.

In this case various other methods, such as interviews, exhibition catalogue,

newspaper reviews, dairies of the artist, letters and so on will compensate the

absence of literature.

5. THOTA VAIKUNTHAM

Thota Vaikuntham was

born in 1942 in Burugupali, Andhra Pradesh, in South

India. He drew inspiration from rural areas of the state, with village men and

women often being central characters in his works. In

particular, women from Telangana have been the main subjects of his

artworks. His

earliest childhood sketches were largely based on the religious figures, Rama,

Hanuman, Krishna, and Ravana, drawn from the great Hindu epic Ramayana, the

engagement that later set the tone for his works based on Hindu iconography. Born to a very modest family his parents understood his passion for art and

allowed him to peruse it as a career, a very rare dispensation in a middle

family. He joined painting department at the College

of Fine Arts, Hyderabad and later had the privilege to continue his

training at the prestigious Faculty of Fine Arts, M S University Baroda. Under the guidance of the great mentor-artist

K G Subramanyan Vaikuntham was able to develop a

sustained engagement with indigenous cultural milieu he was part of and, as a result,

developed a distinctively unique pictorial vocabulary. Vaikuntham,

today, is primarily known for his lifelong artistic engagement with the rural

life of Telangana and rich and vibrant colour plate.

However, he has exuberantly painted figures that explicitly draw from Hindu

iconography, which doesn’t find much mention, and thus becomes the focus of the

present study.

6. ICONOGRAPHY OF KRISHNA

Krishna holds a

significant place in Hinduism as the eighth incarnation of Lord Vishnu and is

revered as the Supreme Lord in his own right. He is adored for his qualities of

compassion, sensitivity, and love, making him one of the most revered gods in

Indian culture. Hindus celebrate Krishna's birthday annually as Krishna

Janmashtami. He is commonly depicted with a flute in hand. In paintings and

sculptures throughout India, Krishna is portrayed in various forms. He has a

beautiful blue body with four arms, holding a lotus flower symbolizing purity,

a crescent moon above his head representing knowledge, and two wheels

representing power. Vredeveld (2022)

In Indian

tradition, Krishna is depicted in various forms, sharing common characteristics

with dark, black, or blue skin colour, as the term

Krishna means black in Sanskrit. In this incarnation, he, like Vishnu, has

slain numerous entities, including his maternal uncle Kansa. His bride in this

form is Rukmini. Dashavatar (2015). However, in ancient and medieval

stone carvings and stone-based artworks Krishna is depicted in human skin

color. In some texts, his body color is poetically described as the color of a

jamun, which is a purple-colored fruit. Vredeveld (2022)

1) Krishna and Govardhan Mountain

Vrindavan is

situated on the banks of the river Yamuna, and Mathura is a city near

Vrindavan. Krishna's life, from infancy to adulthood, unfolded in this place,

making it a significant pilgrimage center for Vaishnavism.

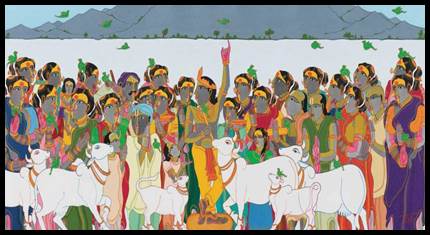

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Krishna Lifting the

Govardhan Hill Sources https://openthemagazine.com/art-culture/thota-vaikuntam-rural-reveries/ |

Figure 1: “Krishna lifting the Govardhan Hill” In this painting, Vaikuntham depicts the

story of Krishna lifting the Govardhan Hill, which was a mountain known as

Govardhan Hill. The story behind this painting is that Krishna lifted the

Govardhan Mountain on his finger to protect the Brajwasis

from Indra's wrath. Krishna is portrayed in a three-fold posture known as the Tribhang Mudra, adding movement to the picture. He is

adorned with jewels and a crown, holding a flute in one hand. The surroundings

feature Brajwasis, animals (cows), and birds (parrots).

Representations of Krishna

(2023)

2) Krishna and the Gopis

The story of

Krishna stealing the garments of gopis bathing in the

Yamuna frequently appears in works of art. The folio from the Bhagavata Purana

manuscript, received in the 16th century, contains its reference. Krishna's

intention in stealing the clothes was to teach the gopis

not to bathe half-naked in the water, as it exposes them to the water deity

(Varun). After learning of this, the

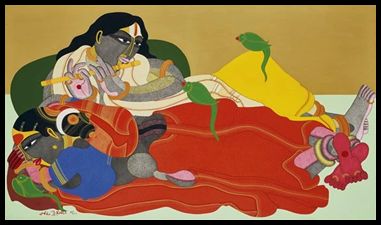

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 Untitled 1942 Acrylic on Canvas, Size: 47.5 x 71.25 Source https://www.mutualart.com/Artwork/Radha-and-Krishna/7FF8BF98A4FC9F56 |

Gopis express

regret to Krishna, who then returns the garments to them. The Gopis desired him

as a spouse due to their affection for him. Representations of Krishna

(2023)

Artists have

portrayed Krishna and the Gopis more frequently, particularly depicting the gopis dancing and chanting around Krishna in what is known

as Ras Leela. The artist positions Krishna at the center of this painting, with

Gopis seated around him. Krishna is depicted playing the flute while dressed in

a blue T-shirt and a white dhoti, symbolizing purity. A parrot sits on his

thigh, and the gopis are shown engaging in various

activities, with each of them having two or more parrots as a symbol of their affection.

The painter effectively demonstrates that despite being involved in multiple

activities, the gopis' focus remains on Krishna. Representations of Krishna

(2023)

3) Krishna and Radha

Radha holds a

special place among the Gopis and is frequently depicted with Krishna in

various settings. The Vaishnava sect, centered around Rama and Krishna, gained

popularity in western, northern, and central India as a Bhakti movement until

the sixteenth century. After that, the movement spread throughout the Indian

subcontinent, and Krishna came to be worshipped not only as a god but also as

an ideal.

Krishna was

regarded as the creator of the universe, while Radha symbolized the human soul.

The devotion of the soul to the Supreme is beautifully portrayed in the Gita

Govinda painting, showcasing Radha's self-sacrifice for her beloved Krishna. Gita Govinda, a remarkable composition

by Jayadeva in the twelfth century, stands as a profound Sanskrit poem where

the dominant Shringar Rasa, or the essence of

romantic love, prevails. Within its verses, the spiritual love shared between

Radha and Krishna manifests in a tangible, physical form, evoking deep emotions

and devotion to its readers. Representations of Krishna

(2023)

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 Radha and Krishna, 2006 Acrylic on Canvas Size: 48 x 72inches Source https://www.mutualart.com/Artwork/Radha-and-Krishna/7FF8BF98A4FC9F56 |

Similarly, in

the fourteenth century, Bhanudatta

crafted the Sanskrit text Rasa Manjari,

a literary masterpiece referred to as the "Bouquet of Bliss." This

enchanting work not only explores the diverse rasas or emotions but also delves

into the intricate differences between the hero (male) and heroine (female)

characters. These distinctions are based on various factors, such as their age

- encompassing childhood, youth, and adulthood - and their individual

characteristics, aptly described through Angik Vaskasajja - categories like Padmini, Trani, Shankhini,

Hastini, and more. Representations of Krishna

(2023) Both Gita Govinda and Rasa Manjari

hold a significant place in Indian literature, showcasing the depth of emotions

and portraying the eternal love and devotion that has captivated the hearts of

countless readers and devotees over the centuries. The richness of their poetry

and the exploration of human emotions continue to inspire and resonate with

audiences, making them timeless classics in the realm of Indian literature. Representations of Krishna

(2023)

7. ICONOGRAPHY OF GANESHA

The name

Ganesha is derived from the combination of two words - "Gana" and

"Ish." "Gana" refers to a "host,"

"crowd," or "an army of deities," while "Ish"

signifies "ruler," "lord," or "sovereign."

Therefore, Ganapati, or Lord Ganesha, can be understood as the "lord of

hosts" or the "Lord of the Gunas." His divine presence holds

significant importance in Hinduism. Forms of Ganesha. (2020)

Lord Ganesha is

known by an array of names and forms, each

representing unique aspects of his divine nature. Some of his well-known

epithets include Vighneshwar, the remover of obstacles; Ekdant, the one with a

single tusk; Siddhi Daata, the bestower of success;

Sumukh, the one with a beautiful face; Kapil, the reddish-brown one; Gajakarnak, with elephant-like ears; Lambodar, the one with

a large belly; Vikat, the formidable one; Vighnanash,

the destroyer of obstacles; Vinayaka, the leader of all beings; Dhumraketu, the one with smoke-hued banner; Gandhakshya, the one with a fragrant aura; Bhalchandra, the

moon-crested one; Gajanan, the elephant-faced; and many more. Each name

encapsulates the divine qualities and attributes of Lord Ganesha, endowing him

with diverse significance and symbolism. Forms of Ganesha. (2020)

In traditional

iconography, Ganesha is often depicted with his consorts, Buddhi and Siddhi,

standing alongside him. Buddhi, representing wisdom and intellect, symbolizes

the power of knowledge and discernment. Siddhi, on the other hand, embodies

success and achievement, representing the fruition of one's endeavors and

spiritual accomplishments. Together, Buddhi and Siddhi are seen as the two

powers of Lord Ganesha, signifying the union of wisdom and success, which are

integral in navigating life's journey with divine guidance and blessings.

Ganesha's divine presence radiates profound wisdom, auspiciousness, and

benevolence, making him a beloved and revered deity among devotees across the

world. Forms of Ganesha. (2020)

Elephant head: The iconic representation of Ganesha

with an elephant head has a fascinating mythological background. When Ganesha's head was

accidentally severed, Lord Shiva brought him back to life by placing the head

of an elephant on his body. In recognition of his bravery and loyalty, Shiva

blessed Ganesha to be worshiped before all other deities. There are three

different versions of the story behind Ganesha’s severed head. Murthy (2017)

According to the first story

described in Varaha Purana, Shiva created Ganesha by mixing five elements.

Because of this, he looked very beautiful and attractive. Due to this, there

was panic among the deities. That is why Shiva increased the size of Ganesha's

stomach and gave the shape of an elephant's head to his head, which would

reduce his beauty and attractiveness. Saffronart (2023)

According to the second story,

due to the sight of Shani Dev, the head of baby Ganesha was burnt to ashes.

Brahma told the sad Parvati that whose head would be found first, his head

would be placed on the head of Ganesha. The first head found was that of a baby

elephant. In this way, Ganesh became 'Gajanan. Kishor (2019)

According to the third story

described in Siva Purana, Mother Parvati created Ganesha from the dirt of her

body. After making him sit at the door, Parvati started taking a bath.

Meanwhile, Shiva came and started entering Parvati's house. When Ganesha stopped

him, an angry Shiva beheaded him. Then, to please the sad Parvati, Shiva placed

the head of an elephant on the head of the child Ganesha. From then onwards,

Ganesh started being called 'Gajanan'. Unveiling the Symbolism of Ganesha (2023).

Ganesha's hands and feet: Ganesha is often depicted with four arms, but in

various forms, he can be seen with 2, 6, 8, 10, or 16 arms, each representing

different attributes. Symbolically, Ganesha's multiple arms signify his ability

to overcome physical and spiritual obstacles. He is portrayed holding various

objects, such as a conch shell, axe, rope, noose, and trident. Like other

deities, Ganesha is often shown seated on a lotus, representing knowledge and

divinity. One of his hands is usually seen in the Abhay Mudra, a gesture of

fearlessness and protection. Furthermore, Ganesha's posture, with one leg on

the ground and the other bent, symbolizes the balance between fulfilling

worldly duties and recognizing our divine nature.

Left-facing trunk and Right-facing trunk: The direction of Ganesha's trunk

also holds significance. When his trunk faces the left, it is called Ganesha Vastu, representing the peaceful aspect of Ganesha and is

preferred for attaining inner peace. Conversely, when his trunk faces the

right, it is known as Dakshinabhimukhi or

Siddhi-Vinayak, depicting a more aggressive and powerful energy.

Broken tusk: In some depictions, Ganesha is shown with a broken

tusk, earning him the name Ekadanta. According to legend, Ganesha used his tusk

as a pen to write the Mahabharata, symbolizing his wisdom and intellect. The

multifaceted symbolism of Lord Ganesha's various attributes reflects his

profound significance as the remover of obstacles, the bestower of blessings,

and the embodiment of wisdom and divine energy in Hindu tradition. Forms of Ganesha. (2020)

The meaning behind some of the characteristic symbols

depicted in Hindu iconography:

·

Big ears and small mouth: listen more and speak less

·

Big head - think big, learn more, and use your intelligence to its full

potential.

·

Small eyes - concentrate, see beyond what you see, and use all senses.

·

Rope - to bring you closer to the highest goal.

·

One Tusk - Keep the Good and Throw the Bad

·

Trunk - high efficiency and adaptability

·

Modak - Reward of Sadhana

·

Axe - To cut all the bonds of attachment

·

Blessings - Blesses and protects on the spiritual path to the Supreme.

·

Big stomach - digest all the good and bad in life calmly

·

Prasad - The whole world is at your feet and begging for you

·

Mouse: Desire, unless controlled, can cause havoc. You ride the desire

and keep it under control and don't let it take you for a ride. Ganesh symbols and their

meanings. (n.d.)

Thota Vaikuntam has painted

several forms of Ganesha in his paintings:

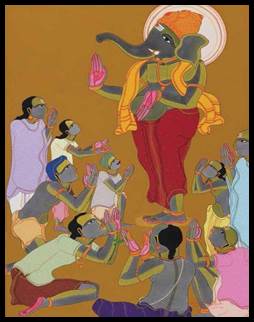

|

Figure 4 Ganesh Pooja by Thota Vaikuntam Source https://openthemagazine.com/art-culture/thota-vaikuntam-rural-reveries |

Figure 4 Ganesh Pooja: The painting depicts the ritual of Ganesh Pooja where

Ganesh is in a standing posture. And his one hand is in Abhay Mudra. According

to Hinduism the two-hand form of Lord Ganesha is known as “Dwibhuja

Ganapati”. He has worn a crown on his head.

There is a circle behind his head, which is called Sahasrar

Chakra, which means thousand, infinite, innumerable Pawandevi (2023). He wears a red color, dhoti. We see

Ganesha is surrounded by many people praying with

folded hands. The sublime scale of Ganesha is shown by making him larger than

the devotees.

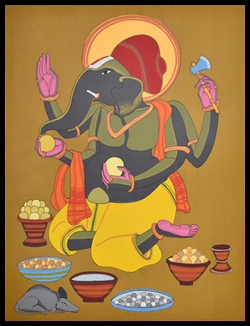

Figure 5

|

Figure 5 Ganesh | serigraph on archival paper | Paper size: 40 x 30 inches, Image size: 35 x 25 inches |

Figure 5 Ganesha (2015): In this painting, the artist has shown the four hands of

Ganesha.

One hand is in

Abhaya Mudra, while the other is holding a Modak. He has a snake tied around his stomach. There

is also a mouse sitting near him, which is his vehicle, which is a symbol of

Ganesha's abilities. The mouse is also called Mooshak.

The mouse

represents wisdom, brilliance, and intelligence, which is presided over by

Ganesha. The mouse symbolizes the ego, which can gnaw at all virtues and must

be tamed. There are some laddoos (sweets) in the basket. Two utensils are also kept near them. And two other hands are in different postures. He is wearing a

blue dhoti. Ganesha’s vaahana.

(2020)

![]()

![]()

8. ICONOGRAPHY OF SHIVA

Shiva, a

Sanskrit word meaning 'auspicious,' is one of the three main deities in

Hinduism and is worshipped as the supreme God. He is also known by several

names, such as Shambhu (gentle), Shankara (benevolent), Mahesh (great Lord),

and Mahadeva (great deity). Shiva is represented in various forms, alongside

his wife Parvati and son Skanda, as the cosmic dancer Nataraja, as a naked

ascetic, a mendicant, a yogi, with a dog (Bhairava),

and even with a body that is half male and half female (Ardhanarishvara),

symbolizing the union of Shiva and his consort.

Shiva embodies

diverse aspects, including being a great ascetic and the Lord of fertility. As

a bisexual deity, he holds dominion over both poison and medicine. His

multifaceted nature makes him a significant and revered figure in Hindu

mythology and spirituality. Doniger (2023)

There

are explained some symbols and their meanings:

·

Moon: Shiva is the element where there is no mind and the moon is the mind's symbol. Without meaning,

'mindless' cannot be expressed or understood. No-mind, infinite consciousness

requires a mind to express itself in the manifested world. So that little mind

(crescent) is on the forehead to describe the indescribable. Wisdom is beyond

the mind, but it needs to be expressed by the touch of the mind, and the

crescent moon symbolizes this. Knowledge is beyond the mind, but it needs to be

expressed with the color of the mind and is symbolized by the crescent moon. Symbolism Behind the Form of

Shiva (2023)

·

Snake: In the state of

meditation, when the eyes are closed, it appears as though the individual is

unconscious, but he is awake. A serpent is depicted around the neck of Lord

Shiva to signify this state of consciousness. To demonstrate Shiva's attention,

they wrapped a serpent around his neck. Therefore, the snake represents

alertness. Snakes are also very sensitive to certain energies. There is a snake

around Shiva's neck. Vishuddhi stops the poison, and the snake carries the

poison. The center of Shiva is considered to be

Vishuddhi, the word Vishuddhi meaning “filter.” Hence, he is also known as Vishkanth or Neelkanth, as he filters all the poisons. Purohit (2015)

·

Third Eye: The third eye of Shiva,

also known as the mystic eye, differs in appearance from the actual eye.

Typically, the third eye remains closed, because as soon as it opens it

unleashes destruction. The third eye symbolizes Shiva's karmic memory.

Generally, Shiva's third eye is viewed as a symbol of power and destruction.

People recognize the third eye as the innate wisdom and knowing eye. His third

eye also symbolizes the rejection of desire. Purohit (2015)

·

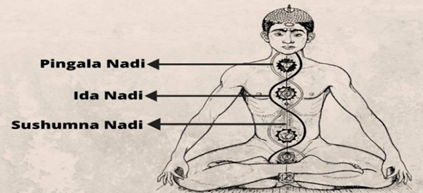

Trident (trishul): Shiva's Trishul represents life's three most important aspects. These are the three basic dimensions of life. They are

also called Ida, Pingala, and Sushumna.

These are the three mains basic nadis referring to

the state of energy in the human body system. These nadis

are left, right, and central. Seventy-two thousand nadis

emanate from these three basic Nadis. The balance between Pingala and Ida makes

us influential in the world; it helps us handle life's aspects. Pingala and Ida

symbolize the basic duality in existence. Shiva’s adornments – the symbols

and symbolism of Shiva. (2015)

|

Source

(Sushumna Nadi), Ida and Pingala Nadi crisscross |

·

Damru: Damru represents his relationship with Shiva.

The two triangles in the Damru symbolize Purusha and

Prakriti and their union, which results in the creation, motion, speech, and

sounds, or Shabda. When they are separated, everything ends

and the mind becomes mute. Damru also represents the Jiva, the embodied soul, who is helplessly entangled in

Shiva's drama and acts based on his own will and strength. The two triangles in

the Damru represent the mind and body, whereas the

Jiva represents its connection to birth and mortality. Rudralife. (2022)

·

The Holi River (Ganga): Ganga is also called the

most river and the goddess of the river; this represents the water coming out

of Shiva's head through the matted hair and falling to the ground, hence the

name Gangadhara, which means “the bearer of the river Ganges.” Shiva is not

only the god of destruction but also the bearer of peace and purity. The Ganges

is also considered a symbol of knowledge.

Surabhi (2020)

·

Nandi (the bull): Shiva's vehicle Nandi

symbolizes eternal waiting; waiting is considered the greatest virtue in Indian

culture. One who knows to sit and wait. he knowns the

true essence of meditation. Nandi does not expect Shiva to come out tomorrow.

He doesn't expect anything. He'll stay forever. This quality is the essence of

receptivity. Before going to any temple, it should have the qualities of Nandi.

Purohit (2015)

·

Figure 6 (Shiva, 2008) In this painting, the artist has painted Shiva in Nataraja form. ('Nataraj' translates to

'monarch of dancers” in Sanskrit (nata = dance, raja = king). It is a unique

form of Shiva. In this form, Shiva is dancing. Therefore, this form is also

called a dance of Shiva (Tandava). According to this form, Shiva is the lord of

the dance. In this Tandava pose, his hair has spread all around. The unusual

form of Shiva as Nataraja is beautifully displayed in this painting. This pose

of Shiva is a wonderful result of artistry. Shiva is dancing in the Tandava

dance style. The lower left hand comes across the chest in Gajahastha

Mudra, pointing to the feet in the air; the lower right hand represents Abhaya

Mudra as a blessing. The Secret Behind Lord Nataraja

form of Lord Shiva. (2023)

Figure 6

|

Figure 6 (Shiva), 2008 Medium: acrylic on canvas, Size:181.6

x 151.2 cm. (71.5 x 59.5 in.) Source https://www.artnet.com/artists/thota-vaikuntam/untitled-shiva-owXWhNbV71KlF7YKbsD_hQ2Untitled |

The Tandava

represents the rhythmic motion and dynamic energy of the universe. According to

Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, Nataraj is “the clearest representation of God's

activity that any art or religion can claim.” It would be hard to discover a

more fluid and dynamic depiction of a moving figure than Shiva's dancing form.”

This cosmic dance of Shiva is called 'Anandtandava,'

meaning dance of bliss, and represents the cosmic cycles of creation and

destruction and the everyday rhythm of birth and death. The dance is a visual

allegory of the five principle manifestations of

eternal energy – Creation, Destruction, Preservation, Moksha and Illusion.

According to Coomaraswamy, Shiva's dance also represents his five activities:

'Srishti' (creation, evolution); 'status' (protection, support); 'Samhara' (destruction, development); 'Tirobhava'

(illusion); and 'Anugraha' (release, liberation, grace).

9. CONCLUSION

In Indian

culture and art, Gods have been revered and worshipped in various forms since

ancient times. These divine beings hold a significant place in society and

religion, with each incarnation teaching unique qualities, virtues, and morals.

As a result of their distinct characteristics, they become the subjects of

iconography. The artist, Thota Vaikuntham, has

skillfully incorporated Hindu iconography into his artworks, evoking timeless

emotions of love and sacrifice for the contemporary society.

Vaikuntham portrays Krishna as the epitome of love and Ganesha as a symbol of renunciation. Krishna as an iconic symbol of love is beautifully articulated in paintings based on Krishna and Radha and Krishna and gopis. Krishna is also depicted as a protector, for instance in the painting titled as Krishna and Gobardhan Mountain, in which Krishna is protecting the cowherds and animals by lifting the mountain on one of his fingers. In the Ganesh Puja artwork, the artist has portrayed the people's faith and devotion to Lord Ganesha. In the depiction of Shiva doing the tandav, Shiva is recognized for his abilities as a destroyer and conservator. Each icon in Hindu iconography holds its own identity and significance. The artist wants to convey a powerful message to art enthusiasts and fellow artists that, despite the numerous representations of Ganesha and Krishna abundantly available in the long history of Indian art, an artist can still revisit, re-think, re-appropriate these perennial symbols of love and sacrifice with renewed energy and great enthusiasm. More importantly, Vaikuntam’s diverse articulations, interpretations, appropriations and adaptations based on Hindu iconography reflect a deep emotion to make these iconic divinities strike a chord with the present world order and inspire the contemporary man to distance from the greed of materialistic yearnings and seek peace in the spiritual way of life taught by the great Hindu religion.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Banerjea, J. N. (1956). The Development of Hindu Iconography. Vikram Jain for Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 1.

Dashavatar. (2015, November 19). Retrieved July 27, 2023, From D’Source.

Doniger, W. (2023, Apr 24). “Shiva” Encyclopedia Britannica. Accessed June 02, 2023.

Forms of Ganesha. (2020, October 23). Retrieved April 2, 2023, from Lord Ganesha.

Ganesh symbols and their meanings. (n.d.). Retrieved from 2023, April 13. thedivineindia.

Ganesha’s vaahana. (2020, August 22). Retrieved from 2023, April 11. Amar Chitra Katha.

Kishor, S. (2019, Sept 2). “Who Is Ganesh Ji?” Patrika News. Accessed 13 Apr 2024.

Murthy, N. (2017, Feb 17). “Bhaavanaatharangam A Retrospective” an Exhibition of Works by Thota Vaikuntam Showcases His Works Spanning Four Decades” The Hindu. Accessed May 18, 2023.

Parimoo, R. (2023). Towards a New Art History: Studies in Indian Art Edited by Shivaji Panikkar, D.K. Print World.

Pawandevi (2023). Sahasrara Chakra - Crown Center. Retrieved From 2023, April 10.

Representations of Krishna (2023). Khan Academy,

Rudralife. (2022, November 25). ‘Damaru’: The Drum of Lord Shiva. Retrieved From 2023, May 14, 2023.

Saffronart - JS Home (2023). Saffronart.com. Accessed 27 July 2023.

Shiva’s adornments – the symbols and symbolism of Shiva. (2015, Summer 2). Retrieved From 2023, May 14. Sadhguru.

Surabhi. (2020, February 18). The Meaning Behind Every Symbol of Lord Shiva. Retrieved From 2023, May 14.

Symbolism Behind the Form of Shiva (2023). The Art of Living (United Kingdom). Accessed May 15, 2023.

The Secret Behind Lord Nataraja form of Lord Shiva. (2023, March 14). Retrieved From 2023, May 15. Statue Studio.

Purohit (2015). The Third Eye of Lord Shiva: Significance and Symbolism (2015). Temple Purohit - Your Spiritual Destination | Bhakti, Shraddha Aur Ashirwad, 24 Aug, 2015. Accessed May 13, 2023.

Unveiling the Symbolism of Ganesha (2023). The Art of Living - Making Life A Celebration, The Art of Living, 8 Aug 2023. Accessed 12 Apr 2024.

Vredeveld, P. (2022). “Krishna, Incarnation of Vishnu, Supreme Being in Hinduism” Original Buddhas, 2022. Accessed July 27, 2023.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.