ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Earthen Art - The Ceramic Heritage of Neolithic Kashmir

Abdul Adil Paray 1![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Manoj Kumar 2

,

Dr. Manoj Kumar 2![]()

![]()

1 PhD

Research Scholar, Department of Ancient Indian History Culture and Archaeology,

Indira Gandhi National Tribal University, Amarkantak, Madya Pradesh, India

2 Faculty,

Department of Ancient Indian History Culture and Archaeology, Indira Gandhi

National Tribal University, Amarkantak, Madhya Pradesh, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Neolithic art

marks a turning point in the evolution of human culture, from roving

hunter-gatherer cultures to permanent agricultural settlements. This change

aided in the development of new technology, social structures, and most

significantly, the advancement of art and craftsmanship. Because of its

practical and ceremonial applications, pottery-making emerged as a prominent

craft. This essay investigates the evolution of art throughout the Neolithic

era, concentrating on the techniques, styles, and cultural significance of

pottery manufacture. The art of the ceramic heritage of Neolithic Kashmir

represents a significant aspect of the Kashmir's early human history,

showcasing the development of pottery and earthen art from the Neolithic

period. This heritage is not just a testament to the artistic skills of

ancient peoples but also provides insights into their daily lives, societal

structures, and interactions with the environment. Neolithic sites in Kashmir

have yielded a wealth of pottery pieces, characterized by their fine

finishes, intricate designs, and functional forms. These artefacts indicate a

high level of craftsmanship and an understanding of ceramic technologies that

were advanced for their time. The pottery often features geometric patterns,

animal figures, and other motifs that may have held cultural or symbolic

significance. The earthenware from Neolithic Kashmir is typically made from

locally sourced clay, shaped by hand or with simple tools, and then fired in

kilns or open fires to achieve durability. The variety of forms—from storage

jars and cooking pots to bowls and plates - suggests a diversified use in

daily activities such as food preparation, storage, and consumption. These

ancient ceramics also provide evidence of trade and cultural exchange.

Variations in styles and techniques between different sites within the

region, and similarities with pottery found in other parts of South Asia,

suggest that Neolithic communities in Kashmir were not isolated but part of a

broader network of interaction. The study of Neolithic Kashmir's ceramic

heritage is crucial for archaeologists and art historians as it helps

reconstruct the lifestyles, technological advancements, and aesthetic

sensibilities of early societies in the region. Additionally, it underscores

the importance of preserving such art and skill at the archaeological sites,

which face threats from environmental factors, urban development, and illicit

trafficking. |

|||

|

Received 03 February 2024 Accepted 11 July 2024 Published 17 July 2024 Corresponding Author Abdul

Adil Paray, adilphd.igntu@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v5.i2.2024.951 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2024 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Neolithic Culture, Pottery, Earthen Art, Heritage,

Kashmir |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Pottery was one of the earliest artistic endeavours that

emerged from the Neolithic era. The development of cooking methods and storing

excess food are two requirements of established life that are frequently linked

to the invention of pottery. Early Neolithic pottery was utilitarian and

simple, but as time passed, it grew more complex and varied, representing the

cultural traits of many areas. The genesis of the art of pottery goes back to

the Neolithic period Burkit (1926), 50-57 in human history, and it marks a significant

advancement in human technological and cultural development. This era began

around 10,000 BCE in some parts of the world Sevizzero

& Tisdell (2014), 10), 4000 BCE – 3000 BCE in the Indian subcontinent Allchin & Bridget (1996), 33 and around 3000 BCE – 2500

BCE in the valley of Kashmir Bandey (2009), 69-70

and 4000 – 3500 BP from Qasimbagh Betts (2019), 17-39.

The Neolithic period saw communities transitioning from nomadic lifestyles to

settled farming and village life. Pottery emerged as a critical innovation,

reflecting changes in human society, economy, and culture. The legacy of

Neolithic earthen art continues to inspire contemporary artists in Kashmir and

beyond, who draw upon ancient motifs and techniques to create modern works in

the industries and factories that reflect the rich cultural history.

The craft of pottery making was a significant art as well as a craft of the Neolithic people, as their primary purpose was the principle of utility with the aesthetic exhibition of it in the form of various designs, decorations, and shapes. In addition, it was a distinguished art of that time because the people experimented, failed, and succeeded, made errors and corrections, changes, and continuities, etc., resulting in the different shapes, sizes, colours, textures, designs, and overall technology for the fabrications of the earthen vessels Shali (1993), 27-33.

Pottery is the most reported artefact retrieved from the surface and in context at the Neolithic sites in Kashmir valley. Like many others, the regional survey’s core methodology was collecting and analysing pottery; understanding potential site interactions and functions by examining them inside or between the sites in an area was one of the important objectives. A diverse range of pottery shreds, varying in fabric, surface treatment, ornamentation, and body parts of vessels, was collected to achieve a balance in the collection process. The fragments of the pottery bases, body pieces, shoulders, neck shreds and rims of different colours, inclusions, and textures with unlike surface treatments like incisions, slips, perforations etc. collected in various contexts including, on the surface, in the vertical sections and piled up by the farmers (most of the sites are under agricultural land) for instance at Hariparigam, Olchibagh, Haigam, Gopus Wudur, etc.

The pottery from all the Neolithic sites under study is

categorized into four types: gritty ware, burnished ware, fine ware, and coarse

ware (Figures 22-29). These four items are regarded as the diagnostic items

from Kashmir’s Neolithic era Ghosh (1964), 19, Mitra (1984), 22-23, Mani (2000), 1-28, Mani (2008), 234, and Bandey (2009), 122-131. Amongst these

four types of diagnostic ware types of pottery, coarse ware (sometimes referred

to as rippled rim pottery) stands out for its use of black and grey colours,

ring and pedestal bases, and surface ornamentation of dots or curvy lines. Due

to surface striations, fine ware—also known as combed grey ware—has been

discovered in two colours: grey and buff. The basket and mat imprint can be seen

on the base, which serves as its distinctive design feature. With pedestals and

flat bases, burnished pottery is mostly available in shades of steel grey and

black, and it has carved triangle motifs on the neck and rim of the vessels.

Gritty porcelain is available in red and buff tones, and many specimens have

pedestal bases without any decoration.

Along with typology, the categorization of pottery offered a

complex analytical tool for identifying and classifying potteries in regions

without local typologies. Since the Neolithic group already had a comprehensive

understanding of hierarchical systems for classifying pottery into broad

groupings like coarse, fine, and burnished ware, classification was clearer Khazanchi

& Dikshit (1980), 49. The primary

criteria for the classification of Neolithic pottery are the raw materials,

clay types, tempers, and embellishments Blakely & Bennett (1989), 6-7. As a result,

Neolithic ceramics were categorized into more or less distinct groups based on

how similar and different their physical and material appearances were.

2. Pottery from Unexcavated Neolithic Sites

The earliest and only excavated Neolithic sites where these

four ceramic styles were discovered are Burzahom, Gufkral, and Kanispora.

During later expeditions to determine the distribution of the Neolithic

material culture in Kashmir, these four ceramic types were also documented from

several locations in Kashmir. The descriptions of these pottery types give the

relative age range of each category of Neolithic pottery in Kashmir Pant et al. (1982), 37-40, Saar (1992), and Bandey (2009), 121–135 discusses the

interpretation of these descriptions. According to their estimates, gritty red

or buff pottery first occurred between 1700 and 1000 BC, followed by burnished

ware between 2000 and 1700 BCE, and coarse grey and fine grey ware between 2000

and 1700 BCE.

The examination of four ceramic categories revealed the

composition of coarse grey ware, which includes spherical cooking pots with

either pedestal or flat bases, rims that ripple, and basins. Selected pieces

from these categories were also drawn. Fine grey pottery is characterized by

bowls, jars, and spherical-bodied pots featuring out-turned collars and

rippling rims. In the production of burnished grey or buff ware, artisans

crafted high-necked jars with flaring rims, globular bodies, flat bases, and

bowls, some with stands, as well as dishes on stands, spherical pots, vases,

and miniature pots. Gritty red or buff porcelain was fashioned into

pedestal-based bowls and small miniature pots. These items are consistent with

the forms found in the archaeological sites of Burzahom, Gufkral, and

Kanispora, as described across the four types of ceramics.

Handcrafted grey ware in a variety of hues, such as dull red, brown, and buff, was among the pottery varieties noted during the field study. Mat imprints are a common characteristic of several varieties, particularly on pots with a flat base, which suggests that they were made on mats. There have been discovered to be several types of exquisite pottery, including jars, funnel-shaped containers, bowls, stems, globular pots, etc. Additionally, the era's pottery assortment featured plates set on hollow stands, stems adorned with triangular perforations, and high-necked jars that boasted flared rims, rounded bodies, and level bases. The technique employed to craft these ceramics was coiling.

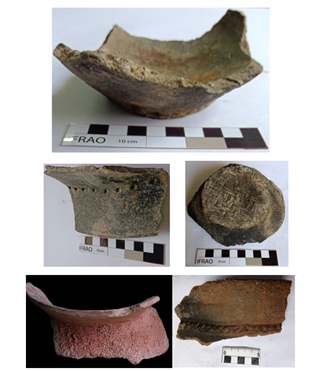

From certain Neolithic settlements yet to be excavated, hand-crafted pottery was unearthed, predominantly in coarse grey, along with some instances of dull, rough red ware and black burnished ware decorated with knobbed patterns. The collection includes a variety of shapes, such as dishes on stands, vases, large jars, bowls, basins, and featuring mat-impressed bases, pinched and reed impressions, and oblique patterns, all with rough textures both inside and out. Additionally, the Neolithic period yielded wheel-turned pottery, encompassing black burnished ware, burnished grey ware, and a small quantity of red gritty ware fragments. The assortment of shapes was expanded to include high-necked jars with flaring rims, rounded bodies, flat bases and cone-shaped vases. The neck area is adorned with pinched and oblique motifs, reed and straw imprints, and bases and sides imprinted with mat and cord. (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10). A few pot shreds are characterized by graffiti marks (Figure 2) in Table 1.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Distribution of Pottery Collected from Unexcavated Neolithic Sites (Average/M2) |

||||

|

Features |

Coarse Grey |

Fine Grey |

Burnished |

Gritty Red |

|

Average No. of Fragments/M2 |

19 |

22 |

14 |

9 |

|

Average Thickness |

4.88 mm |

3.85 mm |

3.76 mm |

3.52 mm |

|

Rims |

6 |

9 |

5 |

3 |

|

Bases |

3 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

|

Shreds |

10 |

9 |

8 |

3 |

|

Common Shapes |

Bowls (5), Vase (3) |

Dish (4), Dish on

Stand (2), Globular Pot (3), Jars (3) and Basins (3) |

Big and Small jars

(3), Bowls (2) and Vases (2) |

Long Necked Jar (1),

Vase (1), shallow cup (1), Dish (2) |

|

Handmade |

12 |

7 |

6 |

3 |

|

Wheel throne |

7 |

15 |

8 |

4 |

|

Designs |

Irregular Reed/Brush

Marks, Mat impression, Finger marks (4) |

Deep incised

brush/combing, Scrapping marks, incised nail decorations, Mat impressions,

obliquely cut rim (7) |

Mat impressions on

base, reed/straw brushed comb surface, Incised oblique, marks, finger marks

(3) |

Pinched designs,

Incised designs (2) |

|

Miscellaneous |

--- |

Cord Impressions (1) |

Knobbed Designs on

Neck region (1) |

--- |

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Neolithic Pot Shreds with Cord and Reed Impressions |

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 The Graffiti on the Neolithic Fine Red Ware and Black Ware from Gufkral |

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 The Burnished Black Ware and Other Wares with Designs from Gufkral and Hariparigam |

Figure 4

|

Figure 4 Neolithic Handmade Pot Shreds |

Figure 5

|

Figure 5 Pot Shreds from Neolithic Sites (Coarse, Burnished, Fine and Gritty Wares) |

Figure 6

|

Figure 6 Fine Grey Ware Pot Shreds from Unexcavated Neolithic Sites |

Figure 7

|

Figure 7 The Designed Fine Grey Ware Pot Shreds from Gopus Wudur and Qasimbagh Neolithic Sites |

Figure 8

|

Figure 8 A Piece of Grey Fine-Wear Handmade Potsherd and a Designed Base of a Dish Stand |

Figure 9

|

Figure 9 A Broken Pot in the Section and the Same Pot After Cleaning |

Figure 10

|

Figure 10 Mat-Impressed Pottery from Unexcavated Neolithic Sites |

Figure 11

|

Figure 11 Plain Bases of Fine Grey Ware Neolithic Pottery |

Figure 12

|

Figure 12 Pot Shreds from Neolithic Sites (Coarse, Burnished, Fine and Gritty Wares) |

Figure 13

|

Figure 13 Buff Ware, Black Ware with Designs, Gritty Red Ware and Coarse Ware |

Figure 14

|

Figure 14 Neolithic Pot Shreds from Various Unexcavated Neolithic Sites |

Figure 15

|

Figure 15 Fine Combed Grey Ware |

Artistic

Description of the Neolithic Pottery

During the field survey, four primary types of pottery were identified: coarse greyware, burnished greyware, gritty, dull redware, and fine greyware. The fine grey ware is distinguishable by its ringing sound and fine texture, colour, thinness, and lightweight nature when struck. The strip method predominates in its preparation. A concise description and illustrations of the most frequently encountered pottery types, both as surface finds and within sections, are provided below:

Most of the pottery of coarse grey clay is mat-impressed, with a few small exceptions for fine grey and rough red ware. The pottery is handcrafted and improperly baked; it is produced with the coil method for creating pots and the strip technique for appliqué. The decorations are distinct and not smudged, which suggests that the pottery was turned on a turntable. Most of the pottery is poorly baked and handcrafted, with no distinction between strip and coil styles.

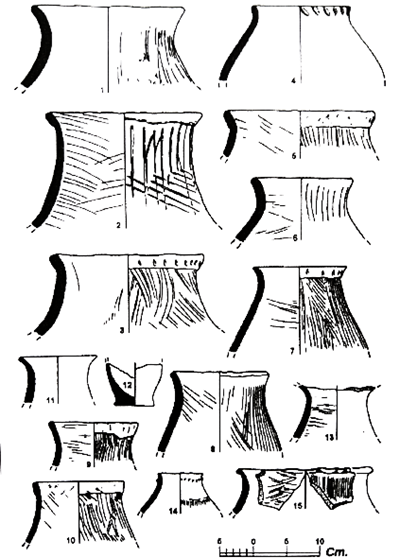

Darkish grey spots are on the surfaces of coarse grey pottery (Item Nos. 1 to 10 in Figure 16), suggesting indifferent firing or reduction conditions. Coarse grey ware is consistently fired to dull grey or dark grey. Gritty red pottery is dull brown, while fine grey pottery is drab or ashy grey. The predominant form has irregular cracks caused by coarse sand grains and is a coarse greyware. The paste comprises particles of quartz, gritty sand, and crushed rock. Quartz and thicker grit were frequently used in the tempering process for large storage pots.

Fine grey ware (13, 14, and 15) has a finer, less porous matrix and thin to medium ceramic thickness. It is consistently burned to an ashy grey or dull grey colour. Sand, crushed rock, and quartz grains make up the majority of the paste's ingredients. (11 and 12) Gritty red pottery has a rougher, porous matrix and is light brown in colour.

The three main utensils come in the following shapes: noat (ghara), matha (matka), daig (handi), dulla (deep basin), tsoad (smaller pitcher), pyala (bowl), and vaer (lota). The matha kinds of Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 15 are contrasted with the tsoad types of Figure 4, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, and Figure 9.

The ceramic has subtle decorations but no noticeable surface treatment. Rims are occasionally lightly pinched or squeezed at predetermined intervals to create a theme. In other situations, softer pinching is more typical. The outside surface of the rim is the only place where ornamental motifs may be found. In one example, a second band is applied externally just below the rim, and the shoulder is systematically grooved and pinched to form a regular pattern of projections and indentations.

Weed, reed, and rush brushing is a surface treatment for pots. An incised pattern is created by the thorough brushing, which is deepest in number 2. Except for the deep basin (dulla) type (item no. 26), which has obliquely horizontal brushing, most pot forms have either vertical or oblique brushing.

Four different brushing techniques are noticed, with imprints that vary in width and depth from wider and deeper to narrower and more spaced. In the shorter sweeps, the lines are appropriately spaced, while in the larger sweeps, the lines are frequently put tightly together. In the thinner ones, the imprints are thin, and it could take some help for the eye to recognise the pattern. Inner surfaces exhibit oblique or horizontal brushing, frequently in an uneven and disorganised manner. Sometimes there isn't any brushing at all.

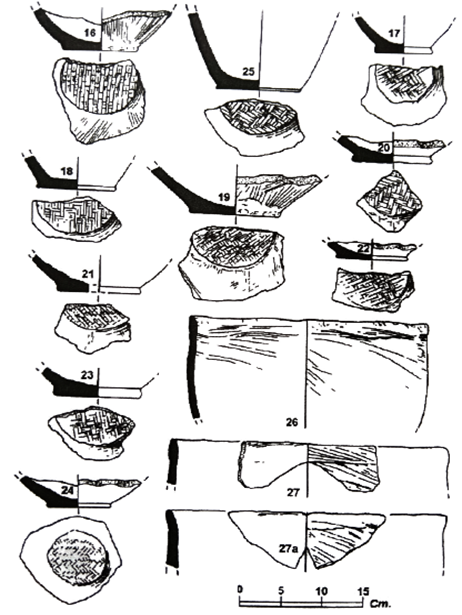

One distinguishing characteristic that shows various weaving patterns is the mat imprint on pot bottoms. It seems like turntable movement was used to shape and dry the pots on mats. Chevron, horizontal and vertical strip combinations, cross-wise patterning, and horizontal and vertical strip patterns are among the available patterns. These patterns offer stimulating areas for further research.

Figure 16

|

Figure 16 Illustrations of Various Neolithic Pottery Types. |

Figure 16, item No. 1. A specimen of

coarse grey pottery with a thick core that shows sand and crushed rock material

with a concave neck and curving rim. The surface has a dull grey colour with

the mouth and neck form of a Kashmiri matha. There is a pinched

decoration design below the rim, and the centre is somewhat unoxidized Smokey

grey.

Item No. 2. An appliqué band creates a curving, outwardly

thickened rim on a piece of coarse grey pottery, displaying a decorative

design. The clay is just somewhat gritty, and the neck is lengthy. With oblique

horizontal brushing in the bottom section and deep outside brushing in the

upper part, the surface has a dull grey colour. The long neck and additional

characteristics point to a Kashmiri matha type—which is utilised in

communities to store grain.

Item No. 3. Crushed rock, gritty sand, quartz inclusions, and

a curving rim with a Smokey grey centre are characteristics of a coarse grey

ware fragment. The shape of the mouth and neck is similar to a Kashmiri matha

type. The rim is gently pinched and features a pattern of depressions and

protrusions. An uneven internal brushing is seen on the periphery.

Item No.4. A shard of coarse grey ware with a smooth rim

point to a Kashmiri deg type vase. There are protrusions and depressions

on the rim due to frequent pinching or pressing. Crushed rock particles and an

unoxidized, Smokey grey core make up the core. The surfaces have a drab, dark

grey colour with faint indications of oblique and vertical brushing. There is

no brushing on the interior surface.

Item No. 5. A shard of coarse grey pottery with an uneven

pattern and an out-curved rim suggests it is of the Kashmiri matha type.

It has dull-grey surface colour, and gently squeezed rim or pinched on the

outside. A crooked design is created by brushing the inner surface.

Item No.6. A shard of coarse grey ware with a curved rim

indicates that it is similar to Kashmiri noat, with a thick core

composed of quartz, grit, and sand. The inside surface is dark grey, and the

outside is drab grey. There is horizontal brushing on the inside surface and

gentle brushing on the outside surface.

Item No. 7. A long-necked vase with a smooth, curving rim on

a piece of coarse grey pottery suggests it is a Kashmiri tsoad type.

Grit, sand, and quartz grains make up the core. The exterior brushing is done

with care, both vertically and horizontally, creating an uneven pattern that

complements the irregular design of the rim.

Item No. 8. A fragment of coarse grey pottery with a curving

rim adorned with a delicately pinched outer rim. A Kashmiri tsoad type

is suggested by the shape of the mouth and neck. There is vertical brushing,

dark grey surfaces, and an unoxidized, smoky grey core with grit and sand.

Item No. 9. A shard of coarse grey ware with soft pinching and

a curved rim, points to a Kashmiri tsoad type. There is a dull grey

exterior and a dark grey interior. The piece of fabric is medium in texture and

has some oblique and vertical brushing.

Item No. 10. A piece of coarse grey pottery with a long neck

and a slightly curved rim points to a Kashmiri tsoad type. There is a

dark brown portion on the inside and a dull grey outside. The fragment is

medium-weight cloth with a core of quartz and sand that is unoxidized and

Smokey grey.

Item No. 11. The fragment, indicative of the Kashmiri vaer

type, is a piece of gritty red ware characterized by a flared rim and an

elongated neck. Its composition is of a coarse texture, incorporating thick

grit, sand, and a core of quartz, devoid of any decorative elements. Evidence

of external brushing using a soft, light material is shown by the presence of

fine horizontal lines on the upper part of the neck.

Item No. 12. A damaged bowl fragment in rough red ware with

dull brown surfaces, no brushing, and a thin, coarse fabric core with grit and

coarse sand tapering to a thick disc base.

Item No. 13. The fragment, identified as a fine grey ware with

a flaring mouth, is indicative of the Kashmiri vaer type. Its exterior

is ashy grey, in contrast to the dull grey interior. The core remains

unoxidized, exhibiting a smoky grey color, with minimal evidence of tempering.

Brushing on the exterior is vertical and spaced irregularly.

Item No. 14. This fragment of exquisite grey pottery has a

narrow, curving rim, a grooved shoulder, and a shape resembling a Kashmiri

vaer (lota). The colour inside the vessel is dull grey, while ashy grey

outside. The inside surface is rough and lacks brushing, while the exterior

surface has an appliqué band with a beaded motif.

Item No. 15. A fine grey ware fragment features a curved rim,

a Kashmiri matha-type mouth and neck, and ashy grey surfaces. Crafted

from fine clay and subjected to minimal tempering, the vase features vertical,

relatively fine brushing on its exterior and irregular brushing within its

interior.

Figure 31, Item Nos. 16 – 24. These are broken

pieces of coarse grey pottery vases, mostly the bases. Most of the vessels

feature bodies that are either thick or of medium thickness, with sides that

narrow down to disc-shaped bases. Cores show heavy grit, sparsely coarse sand,

pulverized rock, and occasionally little quartz fragments found as filler. No.

20's inner surfaces are rough. Nos. 17 and 19 have dark grey surfaces. There

are signs of brushing in nos. 16 - 24; they are primarily obliquely horizontal.

It is highly noticeable in numbers 16 and 19, highlighting the appearance of an

engraved design. The lines in number 24 are quite slim. The impressions of

different patterns left by these shards collectively have a specific meaning

that influences the weaving techniques and patterns of matting.

Item No. 25. A broken, coarse grey ware vase with a deep

bowl-like outline, thick sides, and a mat impression on the base, with no

brushing visible, is found in its lower portion.

Item No. 26. Featuring a thickened rim adorned with an

irregular pattern, this fragment of coarse grey ware has a dark grey surface

and a core filled with thick grit and sand. Its shape is reminiscent of the

Kashmiri dulla type, characterized by horizontal and oblique brushing

patterns. Pots of the dulla type were prevalent in Kashmir valley and

served important roles in religious ceremonies in the recent past.

Item No 27. A fragment of a coarse grey ware vase, larger than

item no. 26, is broken and features a thickened rim. Its exterior is a dull

grey while the interior is brown, showing signs of significant tempering. The

outer surface displays lines from oblique horizontal brushing.

Item No. 27a. A variant of coarse grey ware with a little curved

rim, coarse body surface, and unoxidized smoky grey core with grit content.

Inner surface is rough, outer surface has haphazard brushing.

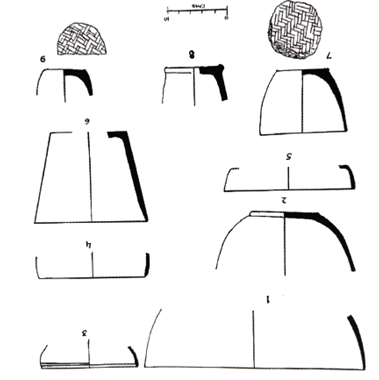

Figure 17

|

Figure 17 Illustrations of Various Neolithic Pottery Types |

Figure 18

|

Figure 18 Handmade Bowls and Basins |

In the above figure (Figure 18), the

illustrations represent the various types handmade basins from various

unexcavated Neolithic sites of Kashmir valley. The shapes include 1. Convex

sided bowl, 2. Convex sided bowel with pedestaled ring base, 3 – 4. Shallow

basin, 5. Shallow basin with straight base, 6. deep bowl with tapering straight

sides and straight base, 7. deep convex sided bowl and base having mat

impression, 8. bowl with straight sides and base having ledge, 9. bowl with

straight base carrying mat impression.

3. Conclusion

The development of shape, fire, and clay processing methods during the Neolithic era was a significant technical advance. Early potters discovered that clay could be shaped into a variety of forms by combining it with water and other ingredients, such as sand or crushed shells. After letting the mixture dry, it was burnt in pits or early kilns to solidify. Neolithic pottery had both practical and symbolic purposes. It transformed food preparation, transportation, and storage in a functional way. Larger, more established populations were supported by the ability to store excess grain and other goods in sturdy, waterproof vessels. Pots and pans for cooking enhanced food preparation methods, while bowls and jars made of clay made resource sharing and transportation easier. The art of Neolithic pottery making varied greatly throughout the Neolithic period due to customs, materials that were accessible, and technical advancements. For instance, The Neolithic man of Kashmir learnt an advancement in pottery-making skills with the invention of wheel-thrown pottery and more complex kilns. On the other hand, hand-building methods like coiling and pinching persisted also. The art of fabrication of the ceramics had a significant impact on society. The emergence of craft specialization and trade networks was probably aided by the requirement for clay supplies, kiln facilities, and specialized skills. Furthermore, the development of complex civilizations, the rise of trade networks, and the population increase may have been aided by the capacity to store and move food more efficiently.

Before the development of the potter's wheel, the Neolithic period employed various hand-building techniques, including coiling and pinching, although these differed depending on the locale. The durability and polish of early Neolithic pottery were restricted by the temperatures that could be reached when firing them in open fires or crude kilns. Neolithic pottery was originally fashioned in modest decorative forms. modest incised lines or impressed patterns created by tools or natural items were frequently used to embellish pots. More intricate designs, including painted decorations made from natural colours, started appearing as time passed. The aesthetics not only expressed details about the social and cultural identities of the people who created them but also had aesthetic appeal.

One of the most important markers of the social and cultural norms of the first agricultural communities is Neolithic pottery. Pottery products' shapes and decorations may convey a variety of social and religious ideas as well as social rank and commercial connections. Ceremonial pottery, for example, is frequently discovered in burial sites and has more intricate patterns, suggesting its use in beliefs and rituals related to the afterlife. Sherds, or pieces of pottery discovered at archaeological sites of Kashmir valley, offer important information on the Neolithic people's food, networks of commerce, and the evolution of their handicrafts. Archaeologists' understanding of the relationships between neighbouring populations and the distribution of Neolithic civilizations throughout different locations has also been aided by studying pottery Yatoo (2012), 197-245.

Neolithic pottery-making reflects the emergence of new social and religious rituals as well as the transition towards established communities, marking an important stage in the history of human culture. We may learn more about the early agricultural communities' everyday routines, cultural customs, and technological innovations by studying Neolithic pottery. Understanding Neolithic art, especially pottery, is essential to comprehending our common history and the underlying principles of civilization. Neolithic art is among the earliest forms of human expression.

The ceramic heritage of Neolithic Kashmir, as encapsulated in the study of Earthen Art, offers a profound glimpse into the region's ancient culture and technological ingenuity. The intricately crafted pottery, with its distinct forms and decorative motifs, not only served utilitarian purposes but also reflected the aesthetic sensibilities and societal values of its creators. Through the lens of these ceramic artefacts, we can trace the evolution of early human settlements in Kashmir, their interactions with the environment, and their advancements in craftsmanship. This heritage, preserved in the clay of bygone eras, continues to resonate with contemporary scholars and enthusiasts, bridging the past and present. By appreciating the ceramic legacy of Neolithic Kashmir, we honour the artistic achievements of our ancestors and enrich our understanding of the historical tapestry that shapes our modern identity.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded and supported by ICHR under File No. 4-01/2021-JRF/ICHR and I also acknowledge the anonymous reviewers.

REFERENCES

Allchin, F.R., & Bridget, A. (1996). Rise of Civilization in India and Pakistan. Cambridge University Press, 33.

Bandey, A. A. (2009). Prehistoric Kashmir: Archaeological History of Palaeolithic and Neolithic Cultures, Dilpreet Publishing House, New Delhi, 69-80, 122-135.

Betts, A., Yatoo, M., Spate, M., Fraser, J., Kaloo, Z., Rashid, Y., Pokharia, A., & Zhang, G. (2019). The Northern Neolithic of the Western Himalayas: New Research in the Kashmir Valley, Archaeological Research in Asia 18, 17-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ara.2019.02.001

Blakely, J. A., & Bennett, W.J. (1989). Analysis and Publication of Ceramics-The Computer Data-Base in Archaeology, BAR International Series, 551, 6-7. https://doi.org/10.30861/9780860546986

Burkit, M.C. (1926). Our Ealy Ancestors. Cambridge University Press, 50-57.

Ghosh, A. (1964). Indian Archaeology 1961-62 A Review. Archaeological Survey of India

Faridabad, 19.

Khazanchi, T.N., & Dikshit,

K.N. (1980). The Grey ware Culture of Northern

Pakistan, Jammu and Kashmir and Punjab. Puratattva, No. 9, The Indian

Archaeological Society, New Delhi, 49.

Mani, B.R. (2000). Excavations at Kanispur: 1998-99 (District Baramulla Kashmir).

Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in History and Archaeology 10, Centre of

Advanced Study, Dept. of Ancient History, Culture, and Archaeology, University

of Allahabd, Allahabad, 1-28.

Mani, B.R. (2008). Kashmir Neolithic and Early Harappan: A Linkage, Pragdhara, 18,

Varanasi, 229-247.

Mitra, D. (1984). Indian Archaeology 1981-82 A Review: Archaeological Survey of India,

Calcutta, 16-25.

Pant, R.K., Gaillard, C., Nautiyal, V.,

Gaur, G.S., & Shali, S.L. (1982). Some New

Lithic and Ceramic Industries from Kashmir, Man and Environment, VI, 37-40.

Saar, S.S. (1992). Archaeology: Ancestors of Kashmir, Lalit Art Publishers New Delhi.

Sevizzero, S., & Tisdell, C.

A. (2014). The Neolithic Revolution and Human

Societies: Diverse Origins and Development of Paths, HAL-02153090, 10.

Shali, S.L. (1993). Kashmir: History and Archaeology through the Ages. Delhi: Indus

Publishing Company, 27-33.

Yatoo, M. (2012). 'Characterising Material Culture to Determine Settlement Patterns in North West Kashmir', Ph. D. Thesis, School of Archaeology and Ancient History, University of Leicester, 197-245.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.