ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Community Radio Broadcasting: Regaining the lost faith and authenticity of radio broadcasting in India

Dr. Lokesh Sharma 1![]()

![]() ,

Anjali Gupta 2

,

Anjali Gupta 2![]()

![]()

1 Associate

Professor, Department of Journalism & Mass communication, Banasthali Vidyapith, Tonk,

Rajasthan, India

2 Research

Scholar, Department of Journalism & Mass communication, Banasthali

Vidyapith, Rajasthan, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The debacle of

conventional broadcast media, in spanning and drawing the local communities

has stimulated the mandate of Community Broadcasting. Through the times,

communal media has risen as a feasible alternative option to the conventional

and recognized media. A highly sought-after kind of civic broadcasting is the ‘Community Radio’, and it is fervently utilized and

functioned in a community, intended for the community and by members of the

community. As the public service broadcaster in India, All India Radio offers

the best radio programming. Nowadays, private FM radio stations are

considered to be second-tier. The third tier,

community radio, promises to be the most accessible. The reach of community

radio in India has significantly increased over the past 20 years. In the country today, there are more than

350 active community radio stations, the majority of which serve rural areas.

In community radio, the creators of information and communications are from

resident communities and delineate local worries and unease through constant

involvement which makes it trustworthy and authentic. The public services

broadcasting has been questioned over the issues of authenticity as it is recognised as the mouthpiece of government whereas

commercial and entertainment-related concerns dominate the

private FM Radio. Community radio uses its own distinctive idioms and

terminology to inform, educate and engage the community using a low cost, low

return model of operation. This paper investigates how the

community radio has emerged as an authentic and trustworthy medium of

communication in the contemporary broadcasting services. The foremost and

widely recognised community radio station in the

Indian state of Rajasthan, Apno Radio Banasthali 90.4 FM has been chosen for conducting the

case study. The conclusions of this research divulge that the community radio

has regained the lost faith and authenticity of radio broadcasting

particularly in terms of information dissemination. |

|||

|

Received 20 January 2024 Accepted 02 June 2024 Published 10 June 2024 Corresponding Author Dr. Lokesh Sharma, sharmaislokesh3@gmail.com

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v5.i1.2024.932 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2024 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Broadcasting, Media, Community Radio, Trust,

Authentic |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The historical account of broadcasting in India is very interesting. The Government of India Act of 1935 permitted state governments to operate radio stations, and after the constitution came into effect in 1950, broadcasting was added to the central list. The narrative story of Indian broadcasting commenced during the colonial time on July 23, 1927 as the foremost station of the Indian Broadcasting Company (IBC) went on the air. During the Quit India Movement, Dr. Ram Monohar Lohia operated an underground radio station for three months in the year 1942 (Sekhar). “Radio broadcasting in India was regulated by the notion that its goal was to generate and distribute a variety of programmes with the aim of educating, enlightening, awakening, and enriching all societal segments during the entirety of the 20th century.” (All India Radio, 2013). The revival of radio truly began in India in 1995 with the launch of FM broadcasting by AIR, where some slots were handed to commercial producers on a sponsorship basis. In 2003, private players were granted licences to run FM radio stations in India, ushering in a period of radio privatisation. This pattern persevered, with an expanding number of FM stations receiving phased licences. Radio sets regained their positions in homes and found spots of their own in buses and auto rickshaws as an outcome largely based on the music-based entertainment programmes, exuberant and energetic Radio Jockeys, and participatory formats that made FM immensely popular, especially among the young people. Atton (2002)

Kolkata has 16 FM stations with a total population of over 14 million in the extended metropolitan area. Nine of these are for-profit businesses, three are nonprofits, and the remaining ones are run by All India Radio. One of the initial four private radio stations in the city of Kolkata, Radio Mirchi, began broadcasting in May 2003. It has continuously been rated as the best station around greater Kolkata region over the last ten years. The Times Group secured the most frequencies after the Indian government chose to grant licences for private FM broadcasting in the year 2000 and launched its very own Private FM radio station under the brand title Radio Mirchi. Balan & Norman (2012)

Community media is a form of participatory and inclusive media that emerged as a result of discontent with mainstream media, its content and coverage. It operates on the ideals of free expression and participatory democracy, fosters community cohesion, and enhances relationships within the community. Gordon (2006) observes that “Community radio is a radio station operated by the community members with community interests in mind without the constraints of making a profit”. As the voice of the voiceless, community radio is a non-profit service that sets itself apart from other forms of media. It symbolises a fresh approach to using the radio medium and advocates for the community's downtrodden citizens. Buckley (2006)

The airwaves are property of the public, conferring to the

1995 ruling of the illustrious Supreme Court of India. Following the

decision of the Supreme Court of India in the year 1995 stating that the air

frequencies are belonging of the public, the concept of "community

radio" has come to the front with the government's sanction of the

creation of radio stations to extremely regarded educational

establishments. It resulted in the

creation of campus radio stations with the ability to broadcast over a range of

10-15 kilometres. Launching at least 4000 community radio stations was part of

the 2006 government's strategy, which was in effect at the time. Dagron (2001)

The 2006 Community Radio Guidelines have made it possible for educational institutions, nonprofit organisations, and agricultural research facilities to launch community radio stations that only broadcast to the surrounding communities. The study area for this study has been determined to be the Rajasthan, a state in the Indian subcontinent. In the state, 22 community radio stations are currently in operation at present (as of the time of writing).

1.1. Conceptual framework

Jürgen Habermas developed the concept of the public sphere, who stated that the public sphere is a domain of social life in which public opinion can be formed. According to Habermas (1992), the public sphere is a place where citizens discuss public issues, a space that serves as a bridge between society and the state. It is open to all citizens and emerges from any dialogue in which individuals come together to form a public. In order to create a public realm, the citizen plays the role of a private individual and discusses the issues of public interest rather than states or private interests. Dutta & Ray (2009)

Saeed (2009) observed that the commercial broadcasting is a market model, whereas public broadcasting is elitist. The elite model reduces public opinion to mass opinion and communication to dissemination, whereas the market model employs participation to position the viewer as a consumer rather than a citizen. Privatization and commercialization of mass communication channels has deteriorated the content in terms of kind and the nature of issues highlighted. The channels influenced by privileged class deliver partial and distorted information to the people. According to Kruse et al. (2018), new modes of communication provide greater interaction and connectivity, both of which are critical for the growth of the public sphere. Hardt (1993)

The need of the hour is for community-based media that can play a neutral and growth-oriented role. The presence of community radio is very significant in an era of market-driven industry and commercialization. Community radio gives opportunities to those who do not have other avenues to express their concerns a platform to do so. It arose from dissatisfaction with mainstream media and serves as an alternative media channel for the community. The present study proposes further exploration of effects of the public sphere in the context of community radio. Sharma et al. (2021)

2. Review of Literature

Reeves

& Nass (1996) observes that “Authenticity has always been a valued characteristic,

but the ever-flowing sea of misinformation and its assumed impact on the masses

has heightened our desire to an additional level. Just as computers become social actors when people treat them like

humans what matters may not be whether a given message exchange meets the

prescribed structural or relational requirements of authentic social

communication, but how much it feels like it does to those participating in or

witnessing it. The current model seeks to account for "communication"

impacts that are not convertible to "message" effects by focusing on

individuals' subjective perception of communication as its primary building

component.” Lee

(2020).

Enli

(2015) in their work “Mediated authenticity: How the media constructs reality”

elaborate on the meaning of legitimacy of communication which is

mediated. The work explains that authenticity involves trustworthiness (i.e.,

being accurate, correct), spontaneity (i.e., being true to oneself, unscripted),

and originality (i.e., being honest, factual). Encompassing former conviction

that centres upon the identity of the communicator or content of the message,

authenticity of communication here denotes to the degree to which an act of communication,

in total, is professed to be realistic and factual. Howley

(2010)

Sharma & Kashyap (2014) in their research “Community

Radio: An Innovative Medium for Capacity Building of Rural People” outlined the

advancements of community radio in India. In contrast to public and corporate

broadcasting, community media is a media service that offers a novel kind of

radio broadcasting. They broadcast material that is widespread and significant

in a particular local market but is occasionally disregarded by media avenues,

including television and commercial ones. The community radio stations embody

regional and significant populations and are run by the groups they represent, and

are controlled, and affected by them. They commonly are not centred on

generating revenue and offer a way for individuals, groups, or communities to

share their tales and experiences, become media contributors and creators in a media-rich

world, and do it in a safe and supportive environment. Jallov

(2012)

Krishna et al. (2017) in the study

“Socio-Technological Empowerment of Rural Households through Community Radio

Stations” puts forward that a significant aspect of community Radio (CR) is

that it is a form of radio which provides platform to the masses of the people

who live for from the urban areas. These people are, in fact, &

under-privileged and underdeveloped and have no access to the media or any

means of communication to give mouth to their feelings. C.R is a direct support

at the ground-level, promotes their expression of thoughts & feelings and

propels local culture as well as the value of their culture. The mem purpose of

C. R. is to make the voice of such people heard, who are deprived of such any

platform: community radio really fulfils its purpose by providing platform for

the volunteers at the local level. In the present day,

community radio serves as a platform for the cultural voluntary sector, civic

society, government agencies, nongovernmental organisations, and local residents to work together to support the development

of their communities. Neighbourhood radio channels, which are the primary

objectives and primacies of this type of broadcasting, also aid their listeners

by presenting a variety of programming containing diverse content. Radio insists

on a reciprocal operation that involves a collaborative process.

Katsaounidou et al. (2019) in the Chapter “Media Authenticity and

Journalism: An Inseparable Framework” discusses the much-needed urgency

of the hour is to re-establish the trust and faith between the media and the

common masses. It seems that the faith has been lost somewhere and we should

focus on re-generating and redeveloping that lost faith between the

newsgathering i.e. news-making and the end- user of the news.

Murada & Sreedher (2019) in their book “Community Radio in India” shares that community radio station can be established, strengthened, and rooted deeply among the masses by involving academics and grassroot organizations. However, the biggest obstacle in developing and sustaining the C.R (s) in the awareness and participation of C.R. volunteers among the mass communities. There is lack of procurement and distribution of quality material and organizing training programmes at the grass root level. Such obstacles need to be put to an end or say they should be rip in the bud at the earliest level/stage. This calls for science initiative, evolving and outlining suitable methodologies to attract donors and those who are dedicated for this honorable cause.

McNair (2000) in their work “Journalism and Democracy: An Evaluation

of the Political Public Sphere” discusses that the majority

of journalists feel that objectivity separates news reporting from other

infotainment or political opinion pieces as the essential component of the

journalism profession. Thus, it is thought that the idea of "Truth"

occupies a prominent position within the news gathering and publishing sector.

Sharma et al. (2022) in his book

“Community Radio and Empowerment: An empirical study on rural empowerment

by Community Radio Statistics of Rajasthan (India)” analysed and inspected the

part played by community radio stations in enabling the pastoral and rural

communities of the state of Rajasthan in India. He also describes the

essentials of community media featuring its foundation and progress across the

globe. Community Radio as well

as the Community Radio Volunteers plays a very vital and substantially

significant role in the displacement of the community ratio concept across the

Globe. In order to achieve this remarkable feat, the

Community radio training programme has a special and

specific role to play. The CR volunteers help in making the community radio popular

among the marginalized communities and help in improving the skill and

awareness of the marginalized communities.

3. Research Questions

The contemporary radio broadcasting in India particularly private FM radio broadcasting is struggling with the credibility and loosing the faith among listeners in terms of reliable and relevant information. It has been proven that community radio is an exceptional channel of communication at grass root level but do the listeners prefer the community radio in comparison to public and private radios? What are the factors and aspects of CRS that build trust in the listeners? Why do listeners have faith in the CRS in terms of relevant reliable and useful information? Such interrogations and questions are the steering force behind the study which will explore how and at what extent the community radio initiatives in Rajasthan (India) are regaining the lost faith of radio broadcasting in India. Khan (2010)

4. Objectives

The main objective

of the study is to understand and analyse the factors and aspects that build

the trust of listeners in the community radio stations and makes the station a

reliable source of information. Nirmala (2015)

5. Research Methodology

The present research is planned and designed as descriptive research wherein content analysis and quantitative analysis methods have been used. The content analysis analysis approach has been adopted to analyze the programme content and quantitative analyse approach has been used to analyse the preferences and choices of listeners pertaining to programme content and various training programmes conducted by the radio stations to motivate and encourage the participation.

5.1. Sampling

The selection of CRS is conducted using the non-probability sampling method known as the purposive sampling method. The measures for choosing a community radio station are (1) Various types of currently operating stations in Rajasthan, (2) well-known stations that have been serving the area for more than 10 years and are located in rural areas. The community radio stations chosen for conducting the study are Tilonia Radio 90.8 FM in Ajmer district of Rajasthan, Radio Madhuban 90.4 FM in Sirohi district, Radio Banasthali 90.4 FM in Tonk district, and Kamalvani 90.4 FM in Jhunjhunu district of Rajasthan. Since they have been serving the community for a long time, all well-recognised community radio stations in the state are well situated in their corresponding communities. (Table 1)

Table 1

|

Table 1 Selected Community Radio Stations |

|||

|

S. No. |

Name of CRS |

Address |

Category |

|

1. |

Kamalvani |

Kamalnishtha Sansthan,

Kolsia, Jhunjhunu- 333042, Rajasthan (India) |

NGO |

|

2. |

Radio Banasthali |

Banasthali Vidyapith, Tonk- 304022 Rajasthan (India) |

Educational |

|

3. |

Radio Madhuban |

Brahma Kumaris, Abu Road, Sirohi – 307510, Rajasthan (India) |

Educational |

|

4. |

Tilonia Radio |

Barefoot College, Tilonia, Ajmer – 305816, Rajasthan (India) |

NGO |

5.2. Selection of listeners

Selection of listeners has been done as per the list of listeners provided by the radio stations. All 100 listeners of the radio stations were selected for the survey using census method. The table below presents the number of respondents recommended by the community radio stations.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Number of Respondents |

||

|

Name of CRS |

No.

of respondents |

Gender |

|

Kamalvani 90.4 FM |

10 |

Female |

|

|

13 |

Male |

|

Radio Banasthali

90.4 FM |

16 |

Female |

|

|

14 |

Male |

|

Radio Madhuban 90.4 FM |

11 |

Female |

|

|

16 |

Male |

|

Tilonia Radio 90.4 FM |

9 |

Female |

|

|

11 |

Male |

|

Total |

100 |

|

5.3. Data Collection

The researcher has made genuine attempts to gather information from a number of sources. Primary data pertaining to listener’s preferences and choices is collected through the telephonic interview using a question schedule containing closed and open ended questions. Secondary data about the programme content is gathered from literature of various national and international journals, business, newspapers, magazines, books, reports, blogs and online databases.

6. Data analysis and interpretation

6.1. Broadcast Profile and programme content

The broadcast

profile of the stations and programme content has been analysed through the

content analysis.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Broadcast Profile of Community Radio Stations |

||||

|

S. No. |

CRS |

Broadcast timings |

Total Hours |

Language of Broadcast |

|

1. |

Kamalvani |

6-11AM; 5-10PM |

10 hrs. |

Hindi and

Rajasthani |

|

2. |

Radio Banasthali |

7-1pm & 4-10pm |

12 hrs. |

Hindi and Rajasthani |

|

3. |

Radio Madhuban |

6AM-10.30PM 10.30 PM (onwards repeat

broadcast) |

24 hrs. |

Hindi, Marwari & Adivasi |

|

4. |

Tilonia Radio |

7 - 9 AM 12 - 2 PM 6 - 9 PM |

7 hrs. |

Hindi and Marwari |

The majority of prevalent programmes are broadcast on community radio stations in Hindi, Rajasthani, and regional dialects, according to their broadcast profiles. Some radio stations broadcast in their native tongues, such as Radio Madhuban, Kamalvani, and Radio Vagad, which all use local languages to broadcast in such as adivasi, shekwati and vagadi respectively. With a focus on skill expansion, sanitation & hygiene, decontamination & neatness, societal support, variability of nature, family government assistance framework, maternal and child welfare, social injustice, social talents, customs and traditions of the civic people and its government assistance standpoint, tobacco free schools, fresco canvases, and people culture of Shekhawati territory, Kamalvani 90.4 FM broadcasts for ten hours every day. Education, health, agriculture, folk art, and culture are the main topics covered by Radio Banasthali 90.4 FM, which broadcasts continuously. With a focus on education, de-enslavement, children, character development, youngsters, women, senior citizens, virtues, leadership, administration, climate, social improprieties, wellbeing and sanitation, and all-inclusive turn of events, Radio Madhuban 90.4 FM broadcasts continuously. Tilonia Radio 90.4 FM broadcasted for seven hours every day with a focus on caste discrimination, gender bias, the NREGA, labour cards, and RTI.

Table 4

|

Table 4 Programmes in Local Language/Dialect |

||||

|

S. No. |

Name of CRS |

Programmes |

Formats |

Duration |

|

1.

|

Kamalvani |

·

Radio Maths, ·

Apni-Dharti-Apna

Log, ·

Apni choupal ·

Maruras, ·

Kuchh baten kuchh geet |

· Discussion · Interviews ·

Field recording ·

Folk Music · Story with folk music |

6hours/day |

|

2.

|

Radio Banasthali |

· GrameenJagat,, · GoanGoanDhaniDhani, · Algoja · MileSurMera Tumhara ·

Apaji ki Siekh |

·

Live-phone in ·

Field recording · Discussion ·

Story with folk music |

6hours/ day |

|

3.

|

Radio

Madhuban |

·

Aashiyana, ·

MeraGaonMeraAnchal, ·

Apno Samaj, ·

Gaon ri batain |

·

Live-phone in ·

Field recording · Discussion · Interviews |

14hours/day |

|

4.

|

Tilonia Radio |

·

MGNREGA mein

chala, ·

Manada Me Vishwas Rakhlo |

· Discussion · Interviews ·

Field recording |

4hours/day |

Table 5

|

Table 5 Kamalvani 90.4 FM |

|||

|

S. No. |

Language of Broadcast |

Broadcast Hours |

% Content |

|

1. |

Hindi |

4 |

40 |

|

2. |

Local language/dialect |

6 |

60 |

|

Total |

10 |

100 |

|

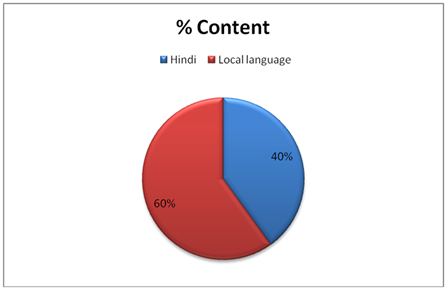

The Kamalvani has become one of the most well-liked radio stations in the area owing to its programmes, which include Radio maths, Maruras, Kuchh baten kuchh geet, Apni chaupal, and Khurjan. The shows take up 6 hours of airtime, or 60% of the total amount of time. The Figure below shows 60% content of the CR is being on aired in local language/dialect.

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 language of Broadcast (Kamalvani 90.4 FM) |

Table 6

|

Table 6 Radio Banasthali 90.4 FM |

|||

|

S. No. |

Language of Broadcast |

Broadcast Hours |

% Content |

|

1. |

Hindi |

6 |

50 |

|

2. |

Local language/dialect |

6 |

50 |

|

Total |

12 |

100 |

|

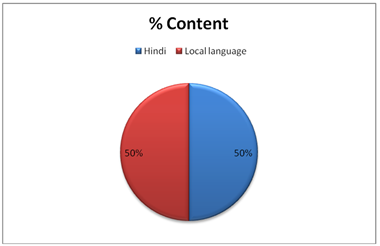

Gramin Jagat, Apaji ki Sikh, Algoja, Gaon gaon dhani dhani, and Mile sur mera tumhara, which are all highly favoured by listeners in rural areas, are among the programmes that the radio station broadcasts for six hours every day. On the listeners' persistent requests, these programmes are broadcasted repeatedly. The diagram below demonstrates that these programmes receive half of the total airtime (12 hours per day) which proves that 50% programme content is being on aired in local language/dialect.

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 language of Broadcast (Radio Banasthali 90.4 FM) |

Table 7

|

Table 7 Radio Madhuban 90.4 FM |

|||

|

S. No. |

Language of Broadcast |

Broadcast Hours |

% Content |

|

1. |

Hindi |

10 |

41.66 |

|

2. |

Local language/dialect |

14 |

58.33 |

|

Total |

24 |

100 |

|

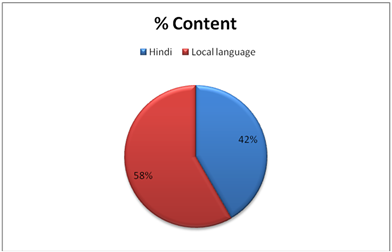

The station aired four programmes with a focus on folk music and culture, including Aashiyana, Apno Samaj, Mera Gaon Mera Anchal, and Gaon ri batain. The overall airtime for the programming, which includes repeat broadcasts, is 14 hours per day, or 58% of the available time. The figure below shows near about 58% programme content is being on aired in local language/dialect while 42% is in Hindi language.

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 language of Broadcast (Radio Madhuban 90.4 FM) |

Table 8

|

Table 8 Tilonia Radio 90.4 FM |

|||

|

S. No. |

Language of Broadcast |

Broadcast Hours |

% Content |

|

1. |

Hindi |

3 |

42.85 |

|

2. |

Local language/dialect |

4 |

57.14 |

|

Total |

7 |

100 |

|

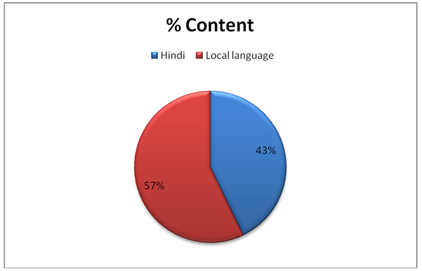

The station does not air programmes with distinct titles, although content-centred traditional songs are performed in numerous programmes grounded on information about festivals, musical instruments, agriculture, culture, and local music. These programmes are broadcast for 4 hours every day, accounting for 57% of the total airtime. The figure below shows near about 57% programme content is being on aired in local language/dialect while 43% is in Hindi language.

Figure 5

|

Figure 4 language of Broadcast (Tilonia Radio 90.4 FM) |

6.2. Listener’s preferences and choices

To know and analyse the preferences and choices of

listeners telephonic interviews are conducted using a question schedule containing

closed ended questions. Frequency distribution tables are used to analyse the

quantitative data and pie charts are used for the graphical representation.

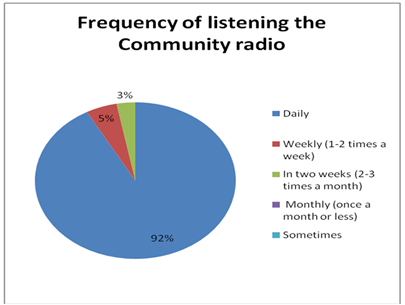

Q1. How often do you listen your CRS?

Table 9

|

Table 9 Frequency of Listening the Community Radio Station |

|||

|

S. No. |

Frequency

of Listening |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

1 |

Daily |

92 |

92.0 |

|

2 |

Weekly (1-2 times a week) |

5 |

5.0 |

|

3 |

In two weeks (2-3 times a

month) |

3 |

3.0 |

|

4 |

Monthly (once a month or

less) |

0 |

0.0 |

|

5 |

Sometimes |

0 |

0.0 |

|

Total |

100 |

100.0 |

|

Table above throws

light on the frequency of respondents listening to the community radio station.

The figure below illustrates that the number of respondents who listen to the

community radio station daily is 92.0%, while only 5.0% respondents listen to

the community radio on weekly basis and 3% of the respondents are found to be

fortnightly listeners of CRS.

Figure 5

|

Figure 5 Frequency of listening the Community Radio Station |

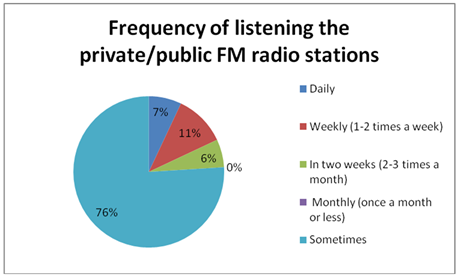

Q2. How often do you listen private/public FM radio stations?

Table 10

|

Table 10 Frequency of Listening the Private/Public FM radio Stations |

|||

|

S.

No. |

Frequency

of Listening |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

1 |

Daily |

7 |

7.0 |

|

2 |

Weekly (1-2 times a week) |

11 |

11.0 |

|

3 |

In two weeks (2-3 times a

month) |

6 |

6.0 |

|

4 |

Monthly (once a month or

less) |

0 |

0.0 |

|

5 |

Sometimes |

76 |

76.0 |

|

Total |

100 |

100.0 |

|

Table overhead demonstrates the number of respondents who listen to private/ public FM radio stations. Findings suggest that 76.0% of the respondents listen sometimes whereas 11.0% of the respondents listen weekly, 6.0% listen fortnightly, and only 7.0% listen to public/private FM radio stations on daily basis. The same data from the table above is shown and condensed graphically in the picture below.

Figure 6

|

Figure 6 Frequency of Listening the Private/Public FM Radio Stations |

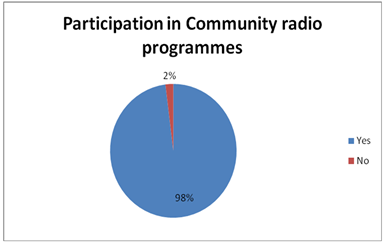

Q3. Do you participate in the programmes?

Table 11

|

Table 11 Participation in Community Radio Programmes |

|||

|

S. No. |

Participation |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

1 |

Yes |

98 |

98.0 |

|

2 |

No |

2 |

2.0 |

|

Total |

100 |

100.0 |

|

The table atop shows the number of respondents who participate in community radio programmes. Findings suggest that 98.0% of the respondents have participated in the programmes. Only 2.0% of the respondents, on the other hand, said that they had not taken part in any programmes. The same data is shown and condensed graphically in the picture below.

Figure 7

|

Figure 7 Participation in Community Radio Programmes |

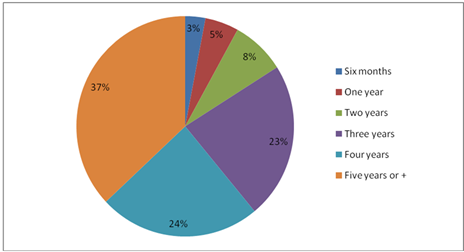

Q4. How long have you been listening to the CRS? For last

Table 12

|

Table 12 Tenure of Listening the CRS |

|||

|

S. No. |

Tenure |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

1 |

Six

months |

3 |

3.0 |

|

2 |

One

year |

5 |

5.0 |

|

3 |

Two

years |

8 |

8.0 |

|

4 |

Three

years |

23 |

23.0 |

|

5 |

Four

years |

24 |

24.0 |

|

6 |

Five

years or + |

37 |

37.0 |

|

Total |

100 |

100.0 |

|

The answers to the questions that were posed to

participants using the CRS to describe the tenure for which they had been

listening are displayed in the table above. The data in this respect showed

that 37.0% of the respondents, or the majority, had been affiliated with CRS

for five years or more. Additionally, it was discovered that 24.0% of the

respondents had worked for CRS for close to four years. 23.0% of the responders

who had been connected to CRS for three years came after this. 8.0% of participants

stated that they have been involved with the CRS for at least the duration of

two years. As a result, just 5.0% and 2.0% of respondents had been linked with

the CRS for the shortest amount of time, an year and

six months, respectively. The graphical representation of the same table is presented

and summarized in the image below.

Figure 8

|

Figure 8 Tenure of Listening |

Q5. Have you attended any Community radio training programme/workshop/activity/seminar?

Table 13

|

Table 13 Participation in

Community Radio Training Programme/Workshop/Activity/Seminar |

|||

|

S. No. |

Participation |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

1 |

Yes |

95 |

95.0 |

|

2 |

No |

5 |

5.0 |

|

Total |

100 |

100.0 |

|

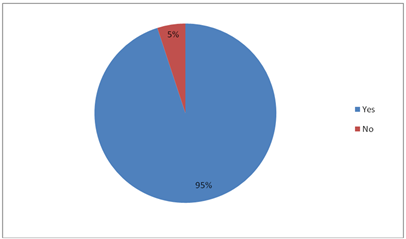

The survey respondents who received training in any

subject through a workshop, activity, or seminar sponsored by Community Radio

are shown in the table above. The results indicate that 95.0% of the

respondents did participate in the courses and receive training from the

lectures, workshops, or other events that were conducted by CRS. Only 5.0% of

the respondents, on the other hand, said that they had not attended any

programmes, lectures, trainings, or other events that CRS hosts.

Figure 9

|

Figure 9 Participation in Community Radio Training Programme/Workshop/Activity |

Q6. What did you learn during the Community radio training

programme/workshop/activity/seminar?

Table 14

|

Table 14 Skills Learnt During the Community Radio Training Programme/Workshop/Activity/Seminar |

||||

|

S. No. |

Skills

learnt |

Yes |

No |

Total |

|

1 |

Script

Writing |

22 |

78 |

100 |

|

2 |

Anchoring/Presentation |

28 |

72 |

100 |

|

3 |

RJing |

7 |

93 |

100 |

|

4 |

Recording |

17 |

83 |

100 |

|

5 |

Editing |

11 |

89 |

100 |

|

6 |

Field

reporting |

10 |

90 |

100 |

|

7 |

Transmission |

5 |

95 |

100 |

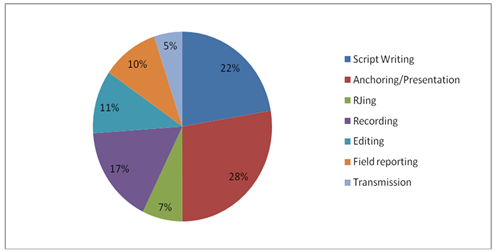

The responses provided to questions on the skills acquired

through the programme, workshops, seminars, or other training events held by

community radio are shown in the table above. Accordingly, it was discovered

that 28% of the respondents, or the majority, had learned anchoring and

presentation. The 22% of individuals who had instruction in script writing came

next. 17% of them were discovered to have taken Recording classes, while 11%

had taken Editing classes. 10% of the participants and 7% of them, respectively,

stated that they had learned field reporting and RJing.

Only 5% of the responders who were still alive claimed to have learned

transmission. The Figure 10 illustrates the same.

Figure 10

|

Figure 10 Skills Learnt During the Community Radio Training Programme/Workshop/Activity/Seminar |

Q7. What makes the CRS interesting in comparison to the private/public FM radio station?

Table 15

|

Table 15 Factors/Aspects of CRS that Makes it Interesting |

||||

|

S.

No. |

Factors/aspects |

Yes |

No |

Total |

|

1 |

Local content |

20 |

80 |

100 |

|

2 |

Programmes in local language/dialect |

30 |

70 |

100 |

|

3 |

Programmes by local

community members |

32 |

68 |

100 |

|

4 |

Filmi Songs |

1 |

99 |

100 |

|

5 |

Advertisements and Jingles |

2 |

98 |

100 |

|

6 |

Folk music/songs |

10 |

90 |

100 |

|

7 |

Interactive formats |

5 |

95 |

100 |

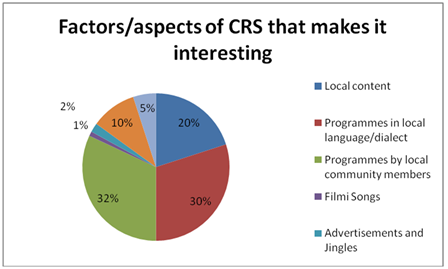

The table above demonstrates the factors of CRS which makes it more interesting and appealing to the respondents. It was found that 32.0% of respondents highlighted programmes by local community members as the major factor, followed by 30.0% of respondents who put emphasis on programmes in local languages, 20.0% of respondents selected local content as an interesting aspect, and 10% were attracted to the folk music/ songs whereas, it was found that 5%, 2% and 1% of respondents favoured Interactive formats, Advertisements & Jingles, and Filmi songs respectively as the interesting aspects of CRS. The Figure 11 depicts the same.

Figure 11

|

Figure 11 Factors/Aspects of CRS that Makes it Interesting |

Q8. What makes the content of CRS reliable and relevant

in comparison to the content of private/public FM radio station?

Table 16

|

Table 16 Factors/Aspects of Content of CRS that Makes it Reliable and Relevant |

||||

|

S. No. |

Factors/aspects |

Yes |

No |

Total |

|

1 |

Local content |

14 |

86 |

100 |

|

2 |

Local style of presentation |

8 |

92 |

100 |

|

3 |

Programmes in local

language/dialect |

32 |

68 |

100 |

|

4 |

Programmes by local

community members |

40 |

60 |

100 |

|

5 |

Interactive formats |

6 |

94 |

100 |

The table above illustrates the factors affecting the reliability and relevance of the content of CRS in comparison to the content of public/private FM radio stations. Findings suggest that 40% of respondents highlighted programmes by local community members as the major factor, followed by 32% of respondents who selected programmes in local languages, 14% of respondents pointed out local content as an interesting aspect, and 8% found the local style of presentation as a relevant factor, and the remaining 6% respondents factored the interactive format of content as a reliable aspect. The Figure 12 depicts the same.

Figure 12

|

Figure 12 Factors/Aspects of Content of CRS that Makes it Reliable and Relevant |

Q9. Do you trust the content of other FM radio

stations? If no, then why

Table 17

|

Table 17 Trust in the Content of Other FM Radio Stations |

||||

|

S. No. |

Trust |

Frequency |

Reason |

Frequency2 |

|

1 |

Yes |

45 |

- |

|

|

2 |

|

|

Do not find it relevant |

18 |

|

3 |

Do not understand language |

12 |

||

|

4 |

No |

55 |

Non-interactive format |

10 |

|

5 |

No feedback opportunity |

10 |

||

|

6 |

Not based on local issues |

5 |

||

The table above displays answers referring to the trust in the content of other FM radio stations. 45% respondents trust the content but 55% respondents do not trust the content for various reasons; 18% are those who do not find it relevant, 12% do not understand the language, 10% find the format of the content non-interactive, the other 10% notice the lack of feedback opportunity and the remaining 5% opine that the content is not based on local issues.

Figure 13

|

Figure 13 Trust in the Content of Other FM Radio Stations |

7. Findings and Discussion

The findings of the research study demonstrate that most of the shows are broadcast in interactive formats. Folk music are sometimes paired with lectures and discussions in certain programmes that use the modern infotainment format to entertain the audience. The local accent and presentational style enhance local culture and forge a connection with the audience. The presentations often employ other forms to add appeal, including live phone-ins, storytelling, and field recordings. According to a comprehensive review of programme content, all of the chosen community radio stations broadcast more than 50% of their programming in the local language or dialect. The data gathered also indicates that, in cooperation with other like-minded groups, the majority of radio stations have successfully implemented their strategies for various community engagement events including training sessions, seminars, fairs, camps, and competitions. The radio station routinely plans events to include and uplift the neighbourhood. Community members are constantly eager to take part in and excel in such activities. The contestants are given the chance to use the airwaves to display their talent. One of the biggest benefits for many of them is listening to their own voice on an FM radio station and sharing their gift. Trust and faith in the CRS are a result of community participation. Rennie (2006), Traber (1985)

8. Conclusion

The programme content of the CRS emphasizes programming that expresses the needs, interests, and diversity of the local community. Engaging listeners through discussions, interviews, and shows that address local issues, culture, and heritage. Participatory approach encourages community participation in radio production. Involve local residents, NGOs, schools, and other organizations in content creation, allowing them to share their stories, ideas, and talents on air. This builds trust with listeners by maintaining transparency in programming, content and information. It ensures that the community radio station operates independently and avoids any biases or conflicts of interest. Broadcast in local languages to reach a wider audience and cater to diverse linguistic communities. Training and capacity building programmes gives opportunities to community members interested in radio production and it ensures quality content creation and helps in nurturing local talent. By focusing on these aspects, community radio stations are striving to regain the lost faith and authenticity in radio broadcasting in India.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Atton, C. (2002). Alternative Media London: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446220153

Balan, K. S., & Norman, S. J. (2012). Community Radio (CR)-Participatory Communication Tool for Rural Women Development-A Study. International Research Journal of Social Sciences, 1(1), 19-22.

Buckley, S. (2006). Community Radio and Empowerment. Background Paper Presented in the 2006 World Press Freedom Day.

CEMCA Career Education Master of Confidence with art Sarkari result Latest News (n.d.).

Community Radio Stations (n.d.). Ministry of Information and Broadcasting.

Dagron, A. (2001). Making Waves: Stories of Participatory Communication for Social Change. New York: The Rockefeller Foundation.

Dutta, A., & Ray, A. (2009, January 29). Community Radio: A Tool for Development of NE. The Assam Tribune [Guwahati], 4 Edit Page.

Enli, G. (2015). Mediated Authenticity: How the Media Constructs Reality. New York: Peter Lang. https://doi.org/10.3726/978-1-4539-1458-8

Frosh, P. (2001). To Thine Own Self be True: The Discourse of Authenticity in Mass Cultural Production. The Communication Review, 4, 541-557. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmz025

Gordon, J. (2006). A Comparison of a Sample of New British Community Radio Stations with a Parallel Sample of Established Australian Community Radio Stations, "3CMedia. Journal of Community, Citizen's and Third Sector Media and Communication, 2, 1-16.

Habermas, J. (1992). The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. Polity Press.

Hardt, H. (1993). Authenticity, Communication, Andcritical Theory. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 10, 49-69. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295039309366848

Howley, K. (2010). Understanding Community Media. London: SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452275017

Jallov, B. (2012). Empowerment Radio - Voices Building a Community (1st Ed.). Gudhjem: Empower House.

Katsaounidou, C. Dimoulas, & A. Veglis (2019). Media Authenticity and Journalism: An Inseparable Framework. IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-5592-6.ch002

Khan, S. U. (2010). Role of Community Radio in Rural Development. Global Media Journal: Indian Edition.

Krishna, D. K., Kumbhare, N. V., Padaria, R. N., Singh, P., & Bhowmik, A. (2017). Socio-Technological Empowerment of Rural Households Through Community Radio Stations. Journal of Community Mobilization and Sustainable Development, 12(1), 56-60.

Kruse, L. M., Norris, D. R., & Flinchum, J. R. (2018). Social Media as a Public Sphere? Politics on Social Media, The Sociological Quarterly, 59(1), 62-84. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380253.2017.1383143

Lee, E. J. (2020). Authenticity Model of (Mass-Oriented) Computer-Mediated Communication: Conceptual Explorations and Testable Propositions. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 25(1), 60-73. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmz025

McNair, B. (2000). Journalism and Democracy: An Evaluation of the Political Public Sphere. Psychology Press.

Murada, P. O., & Sreedher, R. (2019). Community radio in India. Aakar Books.

Nirmala, Y. (2015). The Role of Community Radio in Empowering Women in India. Media Asia, 42(1-2), 41-46. https://doi.org/10.1080/01296612.2015.1072335

Reeves, B., & Nass, C. (1996). The Media Equation: How People Treat Computers, Television, and New Media Like Real People and Places. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rennie, E. (2006). Community Media: A Global Introduction. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Saeed, S. (2009). Negotiating Power: Community Media, Democracy, and the Public Sphere, Development in Practice, 19(4-5), 466-78. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520902866314

Seth, A. (2013). The Community Radio Movement in India. Retrieved From 2018, 25 July 25.

Sharma, A., & Kashyap, D. S. (2014). Socio-Economic Profile of Rural Women in Nearby Areas of Pantnagar Janvani: A Study in Tarai Region of Uttarakhand. Journal of AgriSearch, 1(2).

Sharma, L., Kiran, P., & Kumar, G. (2022). Community Radio Developing the Skills of Self Expression and Public Speaking in Rural Communities. International Journal of Early Childhood Special Education, 14(4), 638-651.

Sharma, L., Rathore, H., & Kiran, P. (2021). Community Radio by Marginalized Communities: A Study of Socio-Economic Profile of Community Radio Volunteers. International Journal of Disaster Recovery and Business Continuity, 12(1), 590-606.

Traber, M. (1985). Alternative Journalism, Alternative Media. Communication Resource, 7 October. London: World Association for Christian Communication. Working Group of 11th Five Year Plan (2007- 2012) - Information and Broadcasting Sector, India 2007.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.