ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Tang-kha Painting: An Appraisal

1 Faculty,

Department of Ancient Indian History, Culture and Archaeology, Panjab

University, Chandigarh, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The present

research paper is on the art of Tang-kha painting. Tang-kha is term

used for the traditional Tibetan scroll painting. It is portable paintings

that one can carry along by scrolling it. Tibetan scroll paintings are famous

for their richness in terms of religious themes and use of vibrant colours.

The art of painting was borrowed from Ancient India and developed by monks of

Tibet. The Tang-kha painting

was a medium to spread the teaching of Buddha among the illiterate through

illustration. The origin and development of Tang-kha painting and its different regional variation along with the

general characteristic feature is discuss in the present paper. |

|||

|

Received 29 January 2024 Accepted 22 February 2024 Published 09 March 2024 Corresponding Author Dr.

Ankush Gupta, ankushgupta010887@gmail.com

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v5.i1.2024.931 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2024 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Tang-Kha, Buddhist Art, Tibetan Art, Cloth Painting |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Tibetan art originated and developed in Tibet and has always been associated with Tibetan Buddhism. Tibetan art can be categorized into jewellery, textiles, paintings, and sculptures in wood, clay, metal, and stucco. Most of these artifacts are religious belonging to Tibetan Buddhism. Tibetan painting is the most popular art, it was introduced in Tibet along with Buddhism from India. It can be divided into three broad categories, these are wall painting, cloth painting, and scroll painting. Tibetan scroll paintings are famous for their richness in terms of religious themes and for preserving the tradition of early Buddhist art. The present paper is an attempt to examine them.

The primary objective of the research study on tang-kha painting is to provide a comprehensive appraisal that explore the historical origins and evolution of tang-kha painting, including the cultural significance and religious contexts in which tang-kha are traditionally used. The research study aims to contribute to a nuanced understanding of artistic techniques, material and style employed in tang-kha painting. The present paper could serve as valuable resource for scholars, art historians and enthusiasts interested in broader context of Tibetan art and its form in term of tang-kha painting. It may also contribute to exploring the influence of early Buddhist art on neighbouring region and the role of tang-kha painting in religious practices.

The traditional Tibetan scroll painting is known as tang-kha, tangka, or thangka, which literary means “thing that one unrolls” usually painted on canvas prepared through cotton or linen cloth. Ras-bris or Ras-rimo is another name used for the tang-kha. The meaning of Ras in Tibetan is cotton and the meaning of ras-bris and ras-rimo is painting or design on cotton. Tang-kha is portable paintings that one can carry along by scrolling it. It is a religious object of Tibetan Buddhism and is used as an aid to various religious practices and teachings. The art of painting tang-kha was borrowed from India and developed by nomadic monks of Tibet. At that time it was known as patta-chitra, which later developed in Tibet as tang-kha. Initially, these nomadic monks travelled extensively to far-flung areas on yaks and horses to spread the teachings of Buddha through tang-kha paintings. When monasteries were built, tang-kha were hung over the walls of shrines for religious and meditation purposes. The tang-kha form of painting developed alongside the tradition of Tibetan Buddhist mural painting, which was mostly painted on the walls of Buddhist monasteries in Tibet.

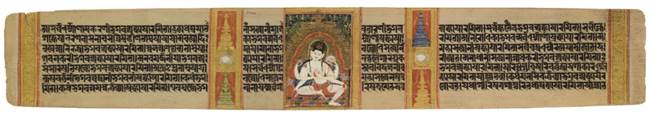

Tibetan Buddhist painting developed from well-known traditions of early Buddhist paintings of Ancient India. The only surviving early Buddhist paintings in India are from Ajanta Caves, Maharashtra. During the Pala period (8th -12th century CE), a similar style of painting continues in a simpler form of illustration on palm leaves. These palm-leaf manuscripts were written and painted for the monks of Buddhist monasteries in Eastern India. These palm leaf manuscripts were made up of dried palm tree leaves with an average dimension of 5cm in height and 60cm in width. The illustrations painted on these manuscripts are of Buddhist deities, usually painted in the centre of the text or in between the columns of text. The size of these painted deities was around 2-3 inches in height and 3-4 Inch in width.

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Palm

Leaf Manuscript of the Ashtasahasrika Prajnaparamita, Pala Period. Source Behrendt (2014), p. 25. |

During the 8th to 12th

century CE, many Buddhist scholars and teachers were invited by the kings of

Tibet for reforming the Buddhist knowledge and religion. For this many Buddhist

scholars (Padmasambhava, Kamalasila, and Santaraksita, Tilopa, Atisa, and Naropa)

reached Tibet with Buddhist palm leaf manuscripts. These Buddhist manuscripts

were translated into local Tibetan script. Because of the unavailability of

palm leaves in the region, they started copying these manuscript's text and

painting on paper. After the downfall of the Pala Empire, the art of palm leaf

manuscript painting ceased to exist in India but continued in the Tibet region

in the form of paper painting. The earliest known Tibetan painting is

stylistically very close to the art of the later Pala and Sena paintings of

Eastern India during the 11th and 12th centuries Huntington (1970). Many Bengali scholars

like that of Atisa, who visited Tibet in the 11th century, also introduced the

art of patta-chitra to the monks of Tibet. Patta-Chitra is

a traditional cloth painting of Bengal and Odisha, which inspired monks of

Tibet to create their own form of patta-chitra; i.e., tang-kha Brown (1920), Pal (1969). Initially Tibetan art

developed from the Pala-Sena art of north-east India.

Three dominant painting

styles were influenced by the Indian sub-continent, showing direct links with

Bengal, Kashmir, and Nepal Stoddard (1996). Other influences on Tibetan art

over the centuries came from Chinese Buddhist art Rowland (1967).

The influence of regional art of Nepal, Kashmir and Central Asia

(Khotan) can be also seen in the tang-kha as well as on wall

paintings of monasteries of western Himalaya and referred to as Himalayan art.

Tibetan painting was originally inspired by geographical proximity Singer (1994), the painting of Central

Tibet is closely related to the art of Eastern Indian art, whereas the painting

of Western Tibet is closely related to the art of Kashmir. The painting of

Eastern Tibet is influenced by Chinese art. This regional variation in the

tang-kha painting style was first noticed by Giuseppe Tucci (1949). Tibetan tang-kha continued

to develop in its distinctive style, which was a mixture of regional art of

Kashmir and Nepal, Tucci called it “Gu-ge

school” Tucci (1949). Most surviving examples of Gu-ge School are from two monasteries –

Alchi in Ladakh and Tabo in Spiti. Around the fourteenth century the landscape

background of some tang-khas were

borrowed from Chinese paintings Rhie & Thurman (1991). Around the seventeenth century the Gu-ge school of art was influenced by

the Chinese regional art, which can be seen in the form of portrayal of

animals, clouds whirls, flames, stylized trees, and cliffs in painting of the

monastic centers and referred to as Sino-Tibetan art.

The art of tang-kha painting is transmitted from master to student through an apprenticeship system, and a student works with a master for many years to learn style and technique Shaftel (1986). Tang-khas were painted by monks as well as lay artists. According to Tucci most of the painters of these tang-kha were laymen Tucci (1949). According to Jackson (1990) “In old Tibet it was the custom for lay people to commission the creation of sacred images, not only to facilitate their religious practice, as meditational aids or as objects of respect and offering, but also to have tang-kha painted in times of sickness or troubles or on the death of a relative or dear one, to assist them in achieving a happy rebirth”. Tang-kha are very rarely signed but, some tang-kha have inscriptions on their back recording that they were the personal meditation image of a monk or a lay person. The scroll paintings are considered sacred and are used to illustrate the life of Buddha, Bodhisattva, religious founders of sect, saints, Tibetan Buddhist deities like Green or White Tara, Avalokiteshwara, or an event from the past and were used for teaching and meditation purposes Khosla (1979). They also depict Kalachakar, Mandalas and Jataka stories in these paintings. The iconographic details are followed as prescribed in Tibetan Buddhist scriptures. Modification of these iconographic details are strictly forbidden.

There

are two types of tang-kha painting based on the material

used, these are as follows- Embroidered (Tsem-tang) and Painted (bris-tang).

The first category required needle and thread work whereas the second category

required colors and brushes. They are further sub-divided into several types,

which include, applique (gos-tang), lacquered (tson-tang),

(nag-tang), or precious bead-inlay tang-kha, gold and silver

thread-tang-kha, and block-printed tang-kha, etc.

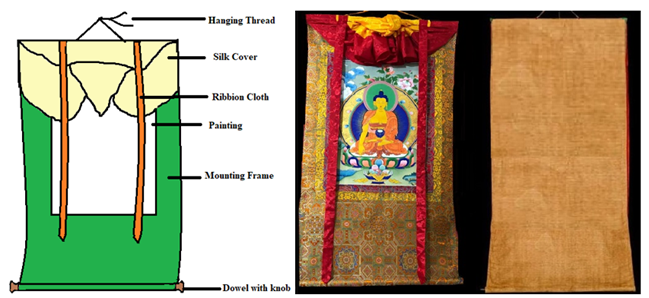

The Tang-kha consists

of different parts, which include – a painting canvas which is mounted on a

cloth frame having a dowel (Thang Thog) rod (Thang

Shing) at both horizontal ends with knobs, strings attached to the

cloth frame for hanging tang-kha on the wall, a

cover made of silk fabric (Zhal Khebs) to protect paintings

for dust and oil fumes and lastly a ribbons ties for securing the tang-kha.

Most tang-kha are portraits in rectangular shape but

square shape tang-kha also exists.

Figure 2

|

Figure 2

A

Diagram of Tang-Kha Showing all Major Parts and Tang-Kha Painting of Medicine

Buddha. (Front and Back). Source Photograph by Author |

The

size of tang-kha varies from 20 cm to 45 meters

in width and 30 cm to 55 Meters in length. Small tang-kha are

usually painted with colours while the large ones are made up of silk threads

by embroidery method. The average width of a traditional tang-kha painting

is 20 inches and the length is around 30 inches. Small tang-kha are

usually hung over the walls of monasteries, houses, doorjambs, and sacred

places. Large tang-kha is unfurled during the

monastery festival or on some special occasions only. Gupta

(2019)

The tang-kha are

painted on canvas prepared from various fabrics. The most used fabrics are

cotton, linen, and silk cloth, few examples in leather or skin also. The use of

leather or animal skin for canvas however is quite rare. Silk canvases are

mostly used in China. The canvas is prepared on a support made up of cotton or

linen cloth, which is taken in the proportion of 4:8 or 2:5 Tucci (1949). This support is called

as kajee in Tibetan. The cotton cloth or support is put in

the stretcher, through four separate bamboo rods, which are sewn on the edges

of the cloth. The canvas is prepared by applying the ground (gesso),

a mixture of fine lime or chalk powder, and animal glue evenly on both sides of

the support and then placed in indirect sunlight to dry. The most common animal

glue used for tang-kha painting is the glue of yak.

Once the surface of the canvas is dry, another coat of ground (mixture of lime

and animal glue) is applied as per requirement. The canvas is then rubbed with

a sea shell or smooth river stone. One should keep rubbing the surface until it

makes no scratch sound. After getting the smooth surface by polishing, the

canvas proceeds for painting which includes several traditional steps Shaftel (1986). These traditional steps are as

follows:

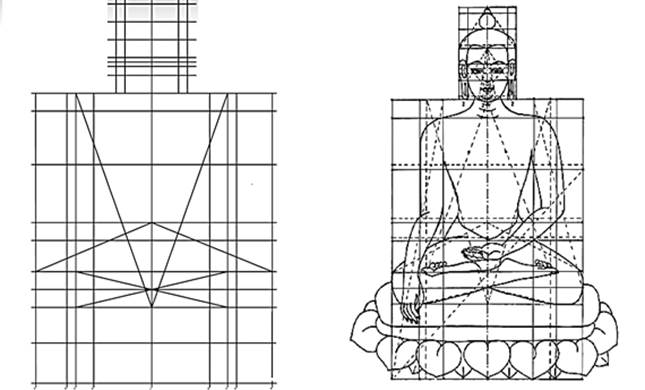

1) Thig-tse (measurement and layout of

canvas)

2) Kya-ri (rough charcoal sketch)

3) Leb-tson (application of flat colors)

4) Ri-mo (outlining of figures by

using dark colors)

5) Dang (shading)

6) Ser-ri (application of gold polish

using Onyx stone)

7)

Rab-ne (consecration ceremony)

In the first step (Thig-tse) geometric markings are marked by using a charcoal marking thread on the backside of the canvas, which divides it into various sections. These geometric markings are marked as per requirement, which forms a grid of angles and intersection lines. It helps the artist to draw a layout of the figures and other background details. After this rough sketch are composed by pencil or charcoal on a grid pattern marked by the charcoal marking on the front side of the canvas. The outline of figures and background is done in the second step (Kya-ri).

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 First (Thig-tse) and Second (Kya-ri) Step of Tang-Kha Painting. Source Drawing by

Stanzin Nurboo |

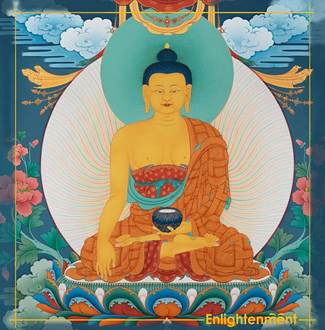

In the third step (Leb-tson), flat colours are applied with a

paintbrush made up of animal hair, mainly rabbit or goat hair used for filling

the colours. The colour, figures, circles, and lines are traditionally fixed

according to Buddhist texts. There are six pure colours, out of which sixteen

basic colours are prepared and used in the scroll paintings. All these colours

are organic colours prepared from minerals and plants. In rare cases, the dust

of gold and silver is used for highlighting the jewellery. These colours are

used one by one, the painting begins with blue colour which is followed by

green, and then other colours are used. The artist first of all prepared the

background by painting the sky followed by the background and then the

foreground. The figures are painted in series with dark colours first and then

followed by lighter colours. The artist starts with dark blue followed by light

blue, green, light green, light orange, then pink, deep orange, red, yellow,

skin colour, gold, and lastly white colour.

Figure 4

|

Figure 4 Tang-Kha

Painting after Application of Flat Colours Source Enlightenment [@enlightenment.thangka]. (2019, February 7). |

Figure 5

|

Figure 5 Tang-Kha

Painting After Completion of Ser-ur Step Source Enlightenment [@enlightenment.thangka]. (2019, March 3). |

After the application of the flat colours, the outline of the figures is marked by the indigo and brownish-red colour in the step called Ri-mo. The hair of the figures is painted in black colour only. The faces and eyes of the figures are always painted in the last. In the fifth step (Dang), dry and wet shading is done by organic dyes. In the next step fine gold lines are marked on the flowers, rocks, leaves, cushions, and robes. Lastly, the gold colour is polished with the help of onyx stone, which gives a lustrous look and is known as the Ser-ri stage. The borders of paintings are painted using red and yellow colours. Once the colours on the canvas is dry, it is cut out from the stretcher, and the final touch is given by stitching to the mounting frame made up of brocade fabric. Securing ribbons, hanging strings, covering silk (Zhal-Khebs), knobs (Thang-Thog), and the rods (Thang-Shing) which keep it stretched laterally are attached to the mounting frame. In the end, there is a consecration ceremony (Rab-ne) for tang-kha painted by monks.

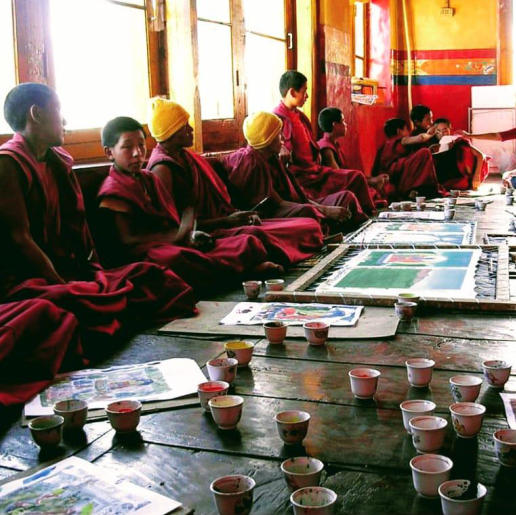

The painting was a medium to spread the teaching of Buddha among the illiterate through illustration. The monks received the basic training in painting and thus were entrusted with the work of decoration in the Buddhist temples. Painting was considered one of the important branches of knowledge Khosla (1979). Tabo monastery is one of the oldest monastery in India, which is located in the Spiti region of Himachal Pradesh impart tang-kha painting to the novice monks. Presently, monks learn and practice the art of painting for six to eight years under a professional monk in the monastery. They are guided by their masters, especially on the use and control of colors related to the representation of sky, fire, and vegetation Tucci (1949). The professional monks train the monks on proportionate representation of facial features, hand, feet, and hair, which is practiced by the students on chalk board. The painters give importance to facial details, hair, eyes, and expressions. The central painted figure used to be the largest and the lines were more stylized and graceful with dynamic and animated pose Khosla (1979). Possibly the central figure was most important and the rest were subsidiary figures. The training was imparted to reproduce real expressions of the figure. This painting style is unique and thus needs to be protected so that practice does not die.

Figure 6

|

Figure 6 Novice

Monks During Tang-Kha Painting Learning Class at Tabo Monastery, Lahual &

Spiti, Himachal Pradesh. Source Photograph

by the Author |

2. CONCLUSION

The

origin of tang-kha painting are

linked to the transmission of Buddhist teaching from India to Tibet. Initially

influenced by Indian artistic traditions, adapting them to convey Buddhist

themes. The cultural exchanges between India and Tibet and neighboring regions,

enriched the iconography, symbolism and techniques seen in tang-kha art today. The intricate details, symbolic representation

and religious narratives found in tang-kha

often reflect the impact of Indian art. The early connection with Indian art

have left a lasting imprint on the style and content of these traditional

Tibetan Buddhist Painting, however tang-kha

art developed its own unique Tibetan style and characteristics, reflecting the

evolving cultural identity of Tibetan Buddhism. Tang-kha became an integral part of Tibetan Buddhist culture. The tang-kha

painting stands as a fascinating testimony to the rich cultural heritage and

artistic expertise rooted in Tibetan and Himalayan traditions. These intricate

paintings were not only used for religious practices, conveying spiritual

teaching through visual representation, but also as aids for meditation and

rituals. Over the centuries, Tang-kha

painting evolved, incorporating unique Tibetan styles and cultural elements.

Its complex details, vibrant colors, and spiritual symbolism not only make it a

visually outstanding masterpiece but also a philosophical expression of

religious devotion.

Figure 7

|

Figure 7 Three Storey Tang-Kha of Lama Rgyalsras Mipham Rinpoche, the Founder of Hemis Monastery, Ladakh. Only Unfurled After a Gap of 12 Years, During Hemis Festival Only. Source Photograph

by Stanzin Nurboo |

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Behrendt, K. (2014). Tibet and India: Buddhist Traditions and Transformations. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 71(3), 4-48.

Brown, P. (1920). Indian Paintings. Association Press.

Enlightenment [@enlightenment.thangka]. (2019, February 7). Making of the Shakyamuni Buddha! Thangka is considered to be a strict art form due it’s Religious [Photograph]. Instagram.

Enlightenment [@enlightenment.thangka]. (2019, March 3). Finally the thangka of shakyamuni Buddha, that we were Working on with Sincere Amount of [Photograph]. Instagram.

Gupta, A. (2019). Education in the Monastic Centers of Western Himalaya AD 950 to 1700 [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. Panjab University.

Huntington, J. C. (1970). The Technique of Tibetan Paintings. Studies in Conservation, 15(2), 122-133. https://doi.org/10.2307/1505472

Jackson, D. (1990). Tibetan Thangka Painting: Methods and Materials. The Tibet Journal, 15(3), 84-86.

Khosla, R. (1979). Buddhist Monasteries in the Western Himalaya. Ratna Pustak Bhandar.

Pal, P. (1969). The Art of Tibet, Asia Society.

Rhie, M., & Thurman, R. (1991). Wisdom and Compassion: The Sacred Art of Tibet. Harry N. Abrams.

Rowland, B. (1967). The Art and Architecture of India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain. Penguin.

Shaftel, A. (1986). Notes on the Technique of Tibetan Thangkas. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, 25(2), 97-103. https://doi.org/10.1179/019713686806027998

Singer, J. C. (1994). Painting in Central Tibet, ca. 950-1400. Artibus Asiae, 54(½), 87-13. https://doi.org/10.2307/3250080

Stoddard, H. (1996). Early Tibetan Paintings: Sources and Styles (Eleventh-Fourteenth Centuries A.D.). Archives of Asian Art, 49, 26-50.

Tucci, G. (1949). Tibetan Painted Scrolls. Libreria Dello Stato.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.