ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Ad Campaigns for Change: Gen Z’s Attitudinal Responses to Pro-Female Advertisements

Manash P Goswami 1![]()

![]() ,

Shiny Angel 2

,

Shiny Angel 2![]()

![]()

1 Professor,

Department of Journalism & Mass Communication, North-Eastern Hill

University, Shillong, India

2 Research

Scholar, Department of Media & Communication, Central University of Tamil

Nadu, Thiruvarur, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Advertising is a potent tool for shaping societal perspectives. India has witnessed a significant transition from traditional gender stereotypes to pro-female approach in advertising in recent years. These advertisements advocating gender equality possess the potential to capture consumers by emphasising the vital role of women across diverse life domains. While television commercials are primarily meant to promote products, they increasingly portray progressive images of women and convey messages that foster liberal perceptions and acceptance of gender equality. Such representations can influence social and psychological perceptions and consumers' brand preferences. This growing affinity for gender equality, reflected in these advertisements, contributes to the broader acceptance of these principles within society. Employing the

snowball sampling technique for data collection, this study was initiated

with a small group of participants in select capital cities of South Indian

states, who then recruited additional individuals from their social networks

to take part in the survey The research investigates the evolving attitudes

of Generation Z towards pro-female advertising across the capital cities of

five southern Indian states: Amaravati, Bengaluru, Chennai, Hyderabad, and

Thiruvananthapuram. It evaluates shifts in attitudes and purchase intentions

by employing Ostrom's ABC Model of Attitude (1969) to examine emotional, behavioural and cognitive changes resulting from exposure

to pro-female advertising. |

|||

|

Received 06 January 2024 Accepted 26 June 2024 Published 30 June 2024 Corresponding Author Shiny

Angel, shinyangelsam@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v5.i1.2024.893 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2024 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Femvertising, Empowerment,

Attitudes, ABC Model, Consumer Behaviour |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The

portrayal of women's roles in countries such as India, where patriarchal norms

are deeply rooted, has typically fallen short of recognising their full

potential and capabilities Grau

& Zotos (2016d), Döring

& Pöschl (2006c). Over time, women have experienced oppression and

in advertising, they are often depicted as homemakers reliant on men or

objectified, whereas men are presented as dominant and authoritarian figures Das

(2000). Most Indian advertisements focus solely on the

portrayals of Indian housewives and hence, this is a pertinent theme since it

remains taboo to discuss issues with sexual connotations Sharma

& Bumb (2021). The representation in question exerts a

significant impact on consumers, particularly among the female demographic, by

engendering body image complexities, eliciting apprehensions regarding

self-esteem, and intensifying societal expectations to conform to constrictive

beauty norms. These advertisements also promote gender norms and contribute to

women's marginalisation by promoting limiting roles, objectification, and

unattainable beauty standards.

Since the

early 1950s and continuing into the present, feminist groups and social

activists have played a pivotal role in advancing women's freedom across

various domains, including politics, society and the economy. Feminism,

considered one of the oldest historical movements, has been the driving force

behind these endeavours. These movements were dedicated to eradicating gender

bias and promoting gender equality. Consequently, waves of feminism play a

significant role in the progression of women’s rights and opportunities Soken-Huberty (2022). The fourth wave of feminism is particularly

concerned with the interaction between the media and Internet usage for social

change Pruitt

(2022), which has given rise to a new advertising trend

known as femvertising. The term 'Femvertising'

is a portmanteau of 'feminism' and 'advertising.' This term was first coined by

the American digital company SheKnows Media, with a

concept centered on presenting pro-female talent,

messages and imagery to empower women and girls through advertising Skey

(2015). This genre of commercials aims to inspire and

empower women through pro-female messages and has gained widespread popularity

in recent years with an increasing number of brands adopting this strategy.

This shift in approach is reshaping the way brands engage with women Rodrigues (2016), and can be seen as a challenge to the

stereotypical representations often found in advertisements Akestam et al. (2017c).

The

advertisement of the popular two-wheeler brand Hero Honda that launched for its

product ‘Pleasure’, endorsed by Bollywood actress Priyanka Chopra in 2006, was

one of the early femvertisements that showcased women

as an independent, confident and assertive individual in their advertising. By

highlighting women's individuality through stylish design options, encouraging

them to embrace personal freedom and make their own choices. This rise of women-empowered

advertisements has brought advertising to the forefront as a potent tool

capable of influencing, shaping and reflecting on purchases and sales. The

significance of advertising has been strengthened by the emergence of femvertising Abokhoza & Hamdalla (2019).

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Screen

Shot from Hero Honda ‘s Pleasure “Why Should Boys Have all the Fun?” (2013) Source Youtube Hero

MotoCorp. (2013) |

Pro-female

advertising has undergone a transformation from stereotypical depictions of

women to more expressive portrayals, effectively resonating with diverse target

audiences. For instance, Dove’s Real Beauty campaign is known for promoting

body positivity and challenging traditional beauty standards. The campaign

features real women of diverse ages, body types and ethnicities rather than

professional models. The campaign encourages self-confidence and a healthy

self-image by celebrating natural beauty (Figure 2). Such impactful advertisements create an

impressive and evoke a sense of inspiration and shift in societal perception

and empowerment among women Aruna

& Gunasundari. (2021).

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 Screen Shot from Dove’s

#StopTheBeautyTest (2022) Source Youtube Dove

India. (2022) |

Thus,

awareness through femvertising makes it a point to

rethink social and gender norms and update with changing societal trends. It is

more or less believed to influence behaviour,

cognitive processes, information and beliefs of society for newer cultural

standards of living to differentiate a company from competing investors Aruna

& Gunasundari. (2021), Raikar

(2020).

The realm

of advertising transcends the dissemination of information. Its multifaceted

objectives encompass informing, educating and persuading audiences to shape

their attitudes and intentions. It ultimately guides them towards making

purchasing decisions. Beyond this immediate impact, advertising also plays a

pivotal role in evaluating enduring benefits, such as brand image, reputation

and emotional values, all of which have the potential to influence consumers,

whether positively or negatively Sadasivan (2019). Within this context, an individual's attitude

towards an advertisement emerges as a critical factor in advertising response MacKenzie et al. (1986c). This concept of attitude, defined as a person's

predisposition to respond positively or negatively to something, seamlessly

extends to attitudes toward advertisements, reflecting how individuals respond

favourably or unfavourably to specific ads during their exposure MacKenzie et al. (1986c).

While

advertising strives to inform, educate, and persuade consumers, it also serves

as a lens through which consumers evaluate enduring brand perceptions

influenced by their attitudes towards the advertisements themselves. In this

intricate interplay, an individual’s attitude becomes linked to the dynamics of

the impact of advertising on consumer behaviour.

Generation

Z, commonly known as Gen Z, which encompasses the population born between

1997-2012 Pew

Research Center. (2023b), is characterised as a hypercognitive generation

comfortable with gathering and cross-referencing information from different

sources and seamlessly merging virtual and offline experiences. They also

exhibit increased global connectivity and acceptance of different ethnicities Gupta

& Gulati (2014). This generation is considered an important target

group for femvertising products and services.

This study

focuses on Gen Z’s attitude towards pro-female advertisements and their

purchasing behaviours for products and services advertised with such messages.

Based on Ostrom’s ABC model of attitude, the impact of pro-female advertising

has been attempted to examine using affective, behavioural and cognitive

components of attitude in this study.

2. Review of Literature

Based on reviews of scholarly papers, reports and

opinions from various sources such as books, websites and magazines, the

essence of the reviewed literature is divided into two distinct sections. The

first section examines studies on attitudes toward femvertising

or pro-female advertising and their corresponding associations. The next

section focuses on studies conducted within the framework of Ostrom's ABC

attitude model.

2.1. Attitude Towards Advertising

As defined

by the American Psychological Association (APA), Attitude represents a

relatively enduring and comprehensive evaluation of an object, individual,

group, issue, or concept, extending from the positive to the negative end of

the spectrum APA

Dictionary of Psychology. (n.d.-d). It signifies an individual's predisposition to

respond favourably or unfavourably to a specific stimulus Lutz

(1985). Attitude plays a pivotal role in advertising Fatima

& Abbas (2016).

Researchers

have investigated the role of attitude as a crucial predictor of consumer

responses to advertising messages, attitudes towards a company or brand, and

the formation of purchase intentions Birmingham (1969), MacKenzie et al. (1986c), Moore

& Hutchinson (1983). Notably, these studies posit that attitude toward

an advertisement can serve as a reliable indicator of its effectiveness MacKenzie & Lutz (1989). Furthermore, research underscores that positive

reactions to advertisements are closely associated with more robust impacts,

including an improved attitude toward the company or brand and a heightened

likelihood of purchase Moore

& Hutchinson (1983). These findings underscore the critical need to

delve into the intricate processes governing the formation and influence of

attitudes in advertising, particularly within the context of femvertising.

Escalas

(2007b) introduced the concept of 'narrative

self-referencing' in the context of femvertising.

This concept postulates that viewers' ability to personally identify and relate

to the female characters portrayed in everyday scenarios within femvertising messages that leads to a more favourable

attitude toward such femvertising messages. This

underscores the influential potential of narrative and relatability in shaping

attitudes towards pro-female advertisements.

The

significance of attitudes towards advertising is pronounced, as it profoundly

shapes consumers' responses to specific advertisements Lutz

(1985), Mehta (2000). A noteworthy observation within the domain of

consumer attitudes towards advertising is that consumers generally have

negative perceptions of television advertising, whereas print advertisements

are often perceived as more engaging and informative compared to broadcast

advertisements; Mittal

(1994), Haller

(1974), Somasundaran & Light (1991).

However,

apart from its direct influence on purchasing behaviour, it is pertinent to

acknowledge that television advertising significantly affects social behaviour Kotwal

et al. (2008). Marketers astutely recognise the influential role

of young demographics, especially children and teenagers, in steering family

purchase decisions. Consequently, they strategically select commercials and

television programs that effectively target this demographic, leveraging their

influence Kraak

& Pelletier (1998), Sashidhar & Adivi (2006). Teenagers have emerged as a formidable

influencing group capable of shaping purchase decisions across diverse product

categories within their families Sashidhar & Adivi (2006). Advertisers, recognising high disposable income,

influence on parental purchases, early brand loyalty, and inclination towards

impulse buying among teenagers, deliberately target this demographic Fox

(1996), McNeal

(1999). Consequently, exposure to television

advertisements augments teenagers' engagement and actively influences their

purchase decisions regarding products advertised on television.

It is

noteworthy that emotional advertisements often yield more favourable brand

attitudes than other advertising formats De Pelsmacker & Geuens (1998c). Research studies have shown that advertisements

incorporate and deliver meaningful messages while evoking emotional responses

are intrinsically linked to the cultivation of more positive attitudes Abitbol

& Sternadori (2020).

Turning our

attention to femvertising, which entails the

promotion of positive and empowering messages centered

on women, research conducted in the Western world suggests that pro-female

advertisements have consistently demonstrated a positive effect on consumers'

attitudes toward brands, particularly among female consumers who are

progressively distancing themselves from stereotypes perpetuated by traditional

advertisements Rodrigues (2016), Skey

(2015). Participants exposed to femvertising

messages consistently reported more positive attitudes towards the products

featured in these advertisements than those exposed to traditional

advertisements Drake (2017b). It is essential to emphasise that values and beliefs play a pivotal

role in shaping consumers' preferences for specific advertising messages,

particularly those that embrace a social stance such as femvertising

Paço & Reis (2012).

2.2. ABC Model of Attitude

Advertising's

influence on consumer behaviour has long been studied by communication

scholars, with advertisers methodically creating messages to enlighten and

convince customers, hoping to elicit favourable responses towards their

products. Attitudes, which are recognised as powerful determinants of purchase

decisions, are crucial to understanding consumer behaviour. These attitudes,

which are thought to have a direct influence on behaviour, are a complex

mixture of feelings, ideas, and behaviours directed against certain objects,

people, things, or events MSEd (2023).

Consumer

reactions are influenced by attitudes, which are reactions to antecedent

stimuli Breckler

(1984b). In the world of advertising, attitudes regarding

promotional activities have a big impact on the final aim of purchase.

Establishing a good attitude towards advertising and brand activities becomes

critical, as it correlates with favourable purchase behaviour and positive

emotional reactions, which serve as critical indicators for measuring

advertising efficiency Sadeghi

et al. (2015b).

In 1969,

Thomas Marshall Ostrom developed the ABC model, a psychological framework for

understanding attitudes. This paradigm deconstructs attitudes into three

interconnected parts: affect, behaviour, and cognition. These components,

generally denoted by the verbs "feel, do, and think," encompass the

emotional, purposeful, and cognitive aspects of a person's reaction to an

attitude object.

The

affective represents a person's feelings, which are reflected in excitement and

trust. behaviour is composed of intentions, verbal statements, and actual acts.

Finally, Cognition integrates knowledge and belief to form the cognitive

dimension. Each of these factors determines how an individual views a subject.

When

evaluating events, things, or people, attitudes are highly interdependent. A

person's attitude is defined by how they react to their circumstances, whether

positively, negatively, or ambivalently Marketing attitudes are long-term

evaluations of a product or service Amin

(2015).

The ABC

model is valuable for academics who are exploring consumer attitudes because it

offers a thorough framework to dissect and understand the subtle dynamics of

emotional, behavioural, and cognitive factors. In the context of advertising,

attitudes have a substantial impact on consumer behaviour.

·

Affective:

In the ABC

model, the affective component is central to understand attitudes Mcleod (2023). It focuses on an individual's emotional response

to attitude objects. Currently, contemporary research challenges the idea that

cognitive beliefs alone shape attitudes Jain

(2014).

According

to Agarwal

& Malhotra (2005), attitude and affect streams should be integrated.

Initially, affect is defined as an emotional response, then evaluative

judgments are based on brand beliefs. Breckler's methodological insights (1984)

propose using verbal reports to measure affect.

As Chi

et al. (2018) point out, positive and negative affective states

add nuance to our understanding. The positive states of confidence, interest

and curiosity are prominent among teens, reflecting an assurance in data

management and a penchant for exploring diverse data types. While the study

noted occasional instances of negative affect, specific examples failed to

emerge. The affective component, positioned as the genesis of the ABC model,

intricately weaves emotions into attitudes. In order to

unravel the intricate dynamics that govern individuals' attitudes toward

objects and phenomena, this nuanced exploration becomes paramount.

·

Behavioural:

The

behavioural facet in Wicker

(1969) ABC model explores overt and verbal dimensions of

behavioural tendencies toward an attitude object. It involves observable

responses reflecting a person's inclination, be it favourable or unfavourable,

to engage with the attitude object. Breckler's insights (1984) describe this as

a dynamic interplay of overt actions, behavioural intentions and verbal

expressions. Defleur & Westie (1963) contributes by highlighting consistency in

attitudinal responses, imparting organisational structure and predictability.

The behavioural component acts as a linchpin, embodying observable

manifestations of attitudes, revealing organised and predictable behavioural

tendencies toward diverse objects.

·

Cognitive:

The cognitive

dimension, integral to attitudes, explores evaluative opinions and beliefs

concerning a specific object. The cognitive component of an attitude

encompasses beliefs, thoughts, and attributes associated with an object,

person, issue, or situation, involving the mental processes of understanding

and interpreting information Mcleod (2023). The cognitive component of an attitude comprises

statements that articulate a spectrum of qualities from desirable to

undesirable, encapsulating the values and attributes attributed to the attitude

object. This includes beliefs concerning the object's properties, its inherent

characteristics and its interrelations with other objects, including the self.

This aspect thus delineates how individuals cognitively perceive and evaluate

an object, thereby shaping their overall attitude towards it Chi et al. (2018).

Within the

context of Generation Z's attitudes toward Femvertising,

the cognitive facet plays a pivotal role. Drawing on insights from scholars

such as Ajzen

& Fishbein (1977b), beliefs in this cognitive domain constitute

foundational information shaping attitudes. As outlined by Breckler

(1984b), the cognitive component includes beliefs,

knowledge structures, perceptual responses and thoughts—creating a cognitive

storage area for organising information that shapes attitudes. The knowledge

function is closely linked to the cognitive component of attitudes, influencing

how individuals interpret and understand their beliefs and perceptions Mcleod (2023). Tri Dinh Le & Nguyen (2014) study on the ABC Model of Attitudes toward Mobile

Advertising aligns with this cognitive framework, emphasising the model's

structured division of attitudes into effect, behaviour, and cognition, thereby

offering valuable insights into Generation Z's attitudes toward Femvertising.

With these

extensive previous research contributions, the current study focuses on the

Generation Z’s attitudes toward Femvertisements

through the following objectives

3. Objectives

1)

To

understand the attitudes of Gen Z Indians towards pro-female advertisements.

2)

To

study the role of pro-female advertisements in motivating a women-empowered

society.

3)

To

investigate the relationship between the response towards pro-female

advertising and the purchasing behaviour of Gen Z.

4. Theoretical Framework

Empirical

evidence suggests that, in the context of advertisements; attitudes, subjective

standards, and perceived behavioural control are vital determinants linked to

the propensity to acquire counterfeit products Wang

(2014). Wang’s study provides useful insights into the

complex decision-making processes of Generation Z consumers.

Osgood and

Tannenbaum’s Congruity Theory further enhances the understanding of consumer

attitudes, as changes in an individual's evaluation and attitude towards

pro-female ads typically shift in the direction of increased alignment with the

person’s existing beliefs and values Ostrom

(1969b). According to Osgood

& Tannenbaum (1955), changes in the evaluation of a phenomenon (or

concept) by an individual are always in the direction of increased congruity

with the existing frame of reference of that individual. Thus, perceived

attitudes toward pro-female advertisements can exert a specific influence on

Generation Z's purchase intentions, ultimately impacting their actual buying

behaviour Long

Yi (2011).

Ostrom’s

ABC model of attitude provides a valuable framework for examining consumer

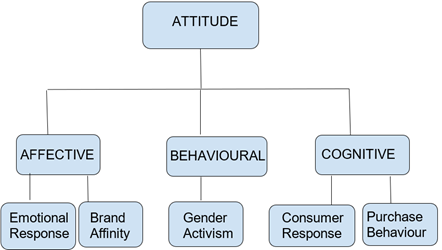

responses to marketing communications. By dividing attitudes into effect,

behaviour and cognition (Figure 3), this model helps elucidate the underlying

psychological processes that influence consumer decision-making Le & Nguyen (2014). Affect represents consumers’ emotional reactions

to advertisements, while behaviour refers to consumers’ intention to act, and

cognition pertains to their beliefs about the product and message of the

advertisement. Understanding the interplay between consumer feelings, thoughts,

and behaviours is essential for marketers to develop effective pro-female

advertising strategies that resonate with Gen Z’s values and aspirations Solomon

et al. (2012).

The three

components of attitude focused on four major variables: emotional resonance,

brand affinity, gender activism, purchasing behaviour, and cognitive response.

The affective component of the ABC model focuses on the emotional facets of the

attitudes. Within this component, two variables were crafted to capture the

nuanced responses. The first variable, emotional resonance with advertising,

measures the depth of emotional engagement and extent of emotional connection

participants experience when exposed to advertising stimuli. The second

variable, brand affinity, assessed the strength of participants’ attachment to

brands featured in advertising. These variables were designed to provide a

comprehensive understanding of emotional responses within the context of

attitudes toward advertising.

The

behavioural component of the ABC model is dedicated to measuring real-world

responses and actions in the context of attitudes towards advertising. Within

the behavioural component of the ABC model, two variables were formulated to

measure real-world responses and actions in the context of attitudes toward

advertising. These are gender activism and purchasing behaviour. Gender

activism assesses the extent to which participants engage in gender-related

activism or advocacy influenced by their attitudes toward advertising. It

offers insights into the practical actions individuals take in response to

advertising messages, particularly those related to gender issues, empowerment,

and inclusiveness. Purchase behaviour examines the impact of participants’ attitudes

toward advertising on their purchasing decisions. It provides valuable insights

into how individuals’ attitudes influence their buying behaviour concerning the

products or services featured in advertisements.

The

cognitive component of the ABC model is dedicated to cognitive processes,

shedding light on how individuals think, process information, and shape their

beliefs. This study examined cognitive responses to advertisements, explicitly

focusing on cognitive responses related to gender equality, empowerment, and

inclusiveness, which provides valuable insights into the cognitive facets of

attitudes.

By applying

Ostrom's ABC model of attitude, marketers can gain a comprehensive

understanding of the hierarchy of effects, allowing them to design targeted

marketing communications that resonate with consumers’ emotions, thoughts, and

behaviours. This knowledge empowers marketers to foster positive brand

relationships and drive Generation Z’s purchase decisions favouring pro-female

brands and products.

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 Model of Ostrom’s ABC Model of Attitude |

This study

attempted to investigate based on Osgood and Tannenbaum’s theory of congruence

and Ostrom’s components of attitudes.

5. Methodology

This study

aims to examine any attitudinal change of Generation Z towards pro-female

advertisements in the capital cities of the southern states of India, that is,

Amaravati, Bengaluru, Chennai, Hyderabad, and Thiruvananthapuram, by employing

Ostrom’s ABC model of attitude. The model comprises three interconnected

components: affective, behaviour, and cognition.

The

affective component of Ostrom’s ABC model focuses on the emotional facets of

the attitudes. It examines how individuals emotionally respond to various

stimuli. The behavioural component encompasses observable actions and responses

stemming from attitudes. It includes the behaviours and decisions that

individuals make based on their attitudes. Finally, cognitive focuses on

cognitive processes. It explores how individuals think, process information,

and form their beliefs. The ABC model considers the dynamic interconnection

among its three components: Affectivity, Cognition, and behaviour.

Affectivity

and Cognition were viewed as independent variables, while behaviour was considered a dependent

variable in the study. Advertisements can elicit both cognitive and emotional

responses in the audience. These emotional or cognitive responses are

recognised as potential influences on subsequent behavioural outcomes. This perspective

emphasises the bidirectional relationship between emotional and cognitive

reactions and their impact on behaviour. The analysis of these

interrelationships can be instrumental in unveiling the intricate dynamics of

play when individuals encounter pro-female advertisements. Specifically, it

will provide insights into how emotional and cognitive responses, whether

separately or in conjunction, contribute to shaping the behaviours of an

individual, namely gender activism and purchase behaviour for such

advertisements.

5.1. Population and Sampling

The target

population for this study consisted of Generation Z individuals residing in the

southern Indian state capitals of - Amaravati, Bengaluru, Chennai, Hyderabad,

and Thiruvananthapuram. Generation Z was defined as those born between 1997 and

2012 Goldring

& Azab (2020b). Using a snowball sampling technique, data were gathered

by distributing questionnaires related to pro-female advertisements through

diverse social networks, such as Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp. The study

included 386 respondents who were actively engaged in the survey. Respondents

were encouraged to share the survey link within their networks to enhance

sample diversity and comprehensiveness.

Data were

collected through a structured questionnaire designed to assess the five key

variables mentioned above, namely, Emotional Resonance, Brand Affinity,

Cognitive Response, Gender Activism, and Purchasing behaviour, which come under

the three components of attitudes (Affectivity, behaviour, and Cognition).

Prior to the implementation, the questionnaire underwent a pilot testing phase

to validate its clarity and relevance.

5.2. Analysis

The present

study utilised statistical analysis to explore Generation Z’s attitudes toward

pro-female advertisements. Descriptive statistics were used to calculate the

mean, which revealed the average attitude score of the respondents. Similarly,

we assessed the role of these advertisements in promoting a women-empowered

society, obtaining the mean perception score through the

"Descriptive" function. To investigate the relationship between

positive emotional responses and purchasing behaviour, Spearman rank

correlation test was conducted. This method revealed any relationship between

emotional responses and consumer actions, shedding light on the influence of

emotions on consumer responses to pro-female advertisements.

6. Results

The primary

objective of this study was to gain a comprehensive understanding of Generation

Z’s attitude toward pro-female advertisements. A number of

crucial attitude variables were meticulously examined to achieve this

objective.

The results

of this study offer valuable insights into the prevailing attitudes within this

demographic. Notably, it was Gen Z, on average, maintained distinctly positive

attitudes toward pro-female advertisements. This positive disposition is

evident in the mean scores, which consistently approach or even exceed four on

a scale ranging from one to five (Table 1).

This

finding underscores a noteworthy trend of favorability

towards pro-female advertising messages among the study participants. The

results suggest a strong inclination towards the themes and narratives

encapsulated in these advertisements, signifying their resonance with the

attitudes of the Indian Generation Z.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Mean Values of Key Variables in Ostrom’s Model in this Study. |

|||||

|

Emot_Res |

Bran_Aff |

Cog_Res |

Gend_Act |

Purch_Beh |

|

|

Mean |

4.04 |

3.8 |

3.85 |

3.81 |

3.67 |

|

Median |

4.25 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

|

Standard

deviation |

0.995 |

1.07 |

1.07 |

1.23 |

1.19 |

6.1. Pro-Female Advertising's Influence on Cognitive Response to Women's Empowerment and Gender Activism

The data

presented in Table 1 indicates that pro-female advertisements

significantly promote a women-empowered society. From the examination of the

cognitive responses of the participants to these advertisements, it is evident

that they believe these advertisements are instrumental in challenging

traditional gender norms and divisions. More specifically, respondents

perceived these ads as promoting self-dependence, breaking down gender

barriers, emphasising inclusivity, and positively influencing views on gender

equality. These findings highlight how these advertisements motivate

individuals toward a more equal society for women.

Additionally,

the high mean score (3.81) for Gender Activism, measured on a scale of 1 to 5,

indicates a strong commitment to gender-related activism among the study

participants. This underscores the idea that these advertisements inspire a

sense of empowerment, motivating individuals to take action to promote gender

equity.

In summary,

pro-female advertisements not only challenge traditional gender norms, but also

inspire concrete actions to break down societal norms and promote inclusivity,

as seen in the cognitive responses of the participants and their commitment to

gender activism.

6.2. Correlation between emotional resonance with femvertising and purchasing behaviour

This study

explored the relationship between Emotional Resonance with Femvertising

and Purchasing behaviour among participants. The analysis revealed a

statistically significant positive correlation between the two variables (r

(361) = 0.55, p < .001) indicating that as emotional resonance with femvertising increases, so does purchase behaviour. In

other words, individuals who report a stronger emotional connection and

engagement with pro-female advertising messages are more likely to exhibit

positive purchasing behaviours influenced by these advertisements.

7. Discussion

This study

provides profound insights into Gen Z’s attitudes towards pro-female

advertisements, revealing a consistently positive disposition. These findings

underscore the resonance between these advertisements and the values of this

demographic, highlighting their favorability for

pro-female advertising messages.

Furthermore,

the study extensively applied Osgood and Tannenbaum’s Congruity Theory and

Ostrom’s ABC Model to comprehend the influence of pro-female advertisements on

attitudes and behaviours. Congruity theory posits that individuals seek harmony

among their beliefs, attitudes, and actions. The results align with this

theory, as participants' positive attitudes towards pro-female advertisements

are congruent with their beliefs about gender equality and women's empowerment.

Additionally,

Ostrom's ABC Model elucidates the cognitive, affective, and behavioural

components of attitudes. The cognitive responses of the participants indicated

that pro-female ads challenged traditional gender norms, promoted

self-dependence, and emphasised inclusivity and gender equality. This aligns

with the cognitive component of the Ostrom's model.

The high

mean score for Gender Activism, measured on a scale from 1 to 5, suggests a

strong commitment to gender-related activism among participants, which is

linked to the behavioural component of Ostrom's model. In summary, pro-female

advertisements not only align with prevailing attitudes but also inspire

concrete actions and commitments in congruence with the theories applied.

8. Conclusion

In

conclusion, this study revealed that Generation Z exhibits positive attitudes

toward pro-female advertisements, aligning with their values regarding gender

equality. The application of the congruity theory and Ostrom’s ABC Model have

deepened our understanding of how these advertisements shape both attitudes and

behaviours. Furthermore, this research underscores that pro-female

advertisements transcend mere attitude influence; they serve as catalysts for

concrete actions and commitments supporting gender equity. This highlights

their influential role in advancing women's empowerment and advocating

gender-related issues.

Moreover, the study identified a significant correlation between favourable attitudes and purchase intentions. Individuals with positive attitudes towards pro-female advertisements are more inclined to engage in positive purchasing behaviour. This finding implies that pro-female advertisements can serve as an effective marketing strategy, particularly in the future. Overall, this research provides valuable insights into the interplay between pro-female advertising, attitudes, behaviours, and marketing strategies, emphasising the enduring significance of pro-female advertisements in shaping consumer perceptions and actions, especially among Generation Z.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

APA Dictionary of Psychology. (n.d.-d).

Abitbol, A., & Sternadori, M. (2020). Consumer Location and Ad Type Preferences as Predictors of Attitude Toward Femvertising. Journal of Social Marketing, 10(2), 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1108/jsocm-06-2019-0085

Abokhoza, R., & Hamdalla, S. (2019). How Advertising Reflect Culture and Values: A Qualitative Analysis Study. Journal of Content, Community & Communication, 10(9). https://doi.org/10.31620/jccc.12.19/12

Agarwal, J., & Malhotra, N. K. (2005). An Integrated Model of Attitude and Affect: Theoretical Foundation and an Empirical Investigation. Journal of Business research, 58(4), 483-493. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(03)00138-3

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1977b). Attitude-Behaviour Relations: A Theoretical Analysis and Review of Empirical Research. Psychological Bulletin, 84(5), 888–918. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.84.5.888

Akestam, N., Rosengren, S., & Dahlén, M. (2017c). Advertising “Like a Girl”: Toward a Better Understanding of “Femvertising” and its Effects. Psychology & Marketing, 34(8), 795–806. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21023

Amin, B. B. A. (2015). Investigating the Impact of Facebook on Consumer Attitude. Florya Chronicles of Political Economy, 7(1), 53–70. https://doi.org/10.17932/iau.fcpe.2015.010/fcpe_v07i1004

Aruna, & K. Gunasundari. (2021). Awareness in Women towards

Femvertising and Their Perception. Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics

Education, 4728-4743. https://doi.org/10.17762/turcomat.v12i6.8650

Birmingham, R. L. (1969). Bauer & Greyser: Advertising in America: The Consumer View. Michigan Law Review, 874-880.

Breckler, S. J. (1984b). Empirical Validation of Affect, Behaviour, and Cognition as Distinct Components of Attitude. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(6), 1191–1205. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.47.6.1191

Chi, Y., Jeng, W., Acker, A., & Bowler, L. (2018). Affective,

Behavioural, and Cognitive Aspects of Teen Perspectives on Personal Data in

Social Media: A Model of Youth Data Literacy. In Lecture Notes in Computer

Science, 442–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78105-1_49

Das,

M. (2000). Men and Women in Indian Magazine Advertisements: A

Preliminary Report. Sex Roles, 43(9/10), 699–717.

https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1007108725661

De Pelsmacker, P., & Geuens, M. (1998c). Reactions to Different

Types of ads in Belgium and Poland. International Marketing Review, 15(4),

277–290. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651339810227551

Defleur, M.L., & Westie, F.R. (1963). Attitude as a Scientific Concept. Social Forces, 42, 17–31. https://doi.org/10.2307/2574941

Dove India. (2022, September

24). Dove | The Beauty Report Card

#StopTheBeautyTest [Video]. YouTube.

Drake,

V. E. (2017b). The Impact of Female Empowerment in Advertising

(Femvertising). Journal of Research in Marketing, 7(3), 593–599.

https://doi.org/10.17722/jorm.v7i3.199

Döring, N., & Pöschl, S. (2006c). Images of Men and Women in Mobile Phone Advertisements: A Content Analysis of Advertisements for Mobile Communication Systems in Selected Popular Magazines. Sex Roles, 55(3–4), 173–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9071-6

Escalas,

J. E. (2007b). Self-Referencing and Persuasion: Narrative Transportation

versus Analytical Elaboration. Journal of Consumer Research, 33(4), 421–429.

https://doi.org/10.1086/510216

Fatima, T., & Abbas, T. (2016). Impact of Advertising Beliefs and Personalization on

Attitude towards Advertising;

Mediating Role of

Advertising Value. International Journal of Business Management and Commerce,

1(2), 10–19.

Fox, R.F. (1996). Harvesting

Minds:

How TV Commercials Control Kids. New Haven, CT: Praeger.

Goldring, D., & Azab, C. (2020b). New Rules of Social Media Shopping: Personality Differences of U.S. Gen Z versus Gen X Market Mavens. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 20(4), 884–897. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1893

Grau, S. L., & Zotos, Y. (2016d). Gender Stereotypes in Advertising: A Review of Current Research. International Journal of Advertising, 35(5), 761–770. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2016.1203556

Gupta, O., & Gulati, G. (2014). Psycho-Analysis of Mobile Applications Usage Among Generation Z Teens. International Journal on Global Business Management & Research, 3(1).

Haller, T.F. (1974). ‘What Students Think of Advertising’.

Journal of Advertising Research.

Hero MotoCorp. (2013, March 4). Hero Pleasure - Raat

mein Fun pe Brake Kyu? [Video].

YouTube.

Jain, V. (2014). 3D Model of Attitude. International Journal of Advanced Research in Management and Social Sciences, 3(3), 1-12.

Kotwal, N., Gupta, N., & Devi, A. P. (2008). Impact of T.V

Advertisements on Buying Pattern of Adolescent Girls. Journal of Social

Sciences, 16(1), 51–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2008.11892600

Kraak, V., & Pelletier, D. L. (1998). How Marketers Reach Young Consumers: Implications for Nutrition Education and Health Promotion Campaigns. Family Economics and Nutrition Review, 11(4), 31.

Le, T.

D., & Nguyen, B. T. H. (2014). Attitudes Toward Mobile Advertising:

A Study of Mobile Web Display and Mobile App Display

Advertising. Asian academy of Management Journal, 19(2),

87.

Long

Yi, L. (2011). The Impact of Advertising Appeals and Advertising

Spokespersons on Advertising Attitudes and Purchase Intentions. African Journal

of Business Management, 5(21), 8446-8457. https://doi.org/10.5897/ajbm11.925

Lutz, R. J. (1985). Affective and Cognitive Antecedents of Attitude Toward

the ad: A Conceptual

Framework. Psychological Processes

and Advertising Effects, 45-64.

MSEd, K. C. (2023). The Components of Attitude.

Verywell Mind.

MacKenzie, S. B., & Lutz, R. J. (1989). An Empirical

Examination of the Structural Antecedents of Attitude Toward the ad in an

Advertising Pretesting Context. Journal of Marketing, 53(2), 48-65.

https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298905300204

MacKenzie, S. B., Lutz, R. J., & Belch, G. E. (1986c). The Role of Attitude Toward the Ad as a Mediator of Advertising Effectiveness: A Test of Competing Explanations. Journal of Marketing Research, 23(2), 130–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378602300205

McNeal, J. (1999).

The Kids Market: Myths and Realities,

Ithaca, NY:Paramount Market

Publishing.

Mcleod, S., PhD. (2023). Components of Attitude: ABC Model. Simply Psychology.

Mehta, A. (2000). Advertising Attitudes

and Advertising Effectiveness. Journal of Advertising Research.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2501/JAR-40-3-67-72

Mittal,

B. (1994). Public Assessment

of TV Advertising: Faint Praise

and Harsh Criticism. Journal of Advertising Research, 34(1), 35–53.

Moore,

D. L., & Hutchinson, J. (1983). The Effects

of ad Affect on Advertising Effectiveness. ACR North

American Advances.

Osgood, C. E., & Tannenbaum, P. H. (1955). The Principle of Congruity in the Prediction of Attitude Change. Psychological Review, 62(1), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0048153

Ostrom, T. M. (1969b). The Relationship Between the Affective,

Behavioural, and Cognitive Components of Attitude. Journal of Experimental

Social Psychology, 5(1), 12–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(69)90003-1

Paço, A. D., & Reis, R. M. M. (2012). Factors Affecting Skepticism toward Green Advertising. Journal of

Advertising, 41(4), 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2012.10672463

Pew Research Center. (2023b, May 22). Where Millennials end and Generation Z Begins | Pew Research

Center.

Pruitt, S. (2022). What are the Four Waves of Feminism? HISTORY.

Raikar, C. (2020).

Women Empowerment and Advertising: Identifying Liberated Spaces Created by “Ariel’s# Share the Load Campaign in India”.

Rodrigues, R. A. (2016). Femvertising: Empowering Women Through the Hashtag? A Comparative Analysis of Consumers’ Reaction to Feminist Advertising on Twitter (Doctoral dissertation, Universidade de Lisboa (Portugal)).

Sadasivan, A. (2019). Attitude Towards Advertisements: An Empirical Study on the Antecedents. Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4036100

Sadeghi, M., Fakharyan, M., Dadkhah, R.,

Khodadadian, M. R., Vosta, S. N., & Jafari, M. (2015b).

Investigating the Effect of Rational and Emotional Advertising Appeals of

Hamrahe Aval Mobile Operator on Attitude towards Advertising and Brand Attitude

(Case Study: Student Users of Mobile in the Area of Tehran). International

Journal of Asian Social Science, 5(4), 233–244.

https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.1/2015.5.4/1.4.233.244

Sashidhar, A. S. and Adivi, S. (2006). Advertising to Kids Is It Justified? Advertising Express, September, 12-16.

Sharma, S., & Bumb, A. (2021). Role Portrayal of Women in Advertising: An Empirical Study. Journal of International Women's Studies, 22(9), 236-255.

Skey, S. (2015). Femvertising A New Kind of Relationship Between

Influencers and Brands.

Soken-Huberty, E. (2022). Types of Feminism: The Four Waves. Human Rights Careers.

Solomon,

M., Russell-Bennett, R., & Previte, J. (2012).

Consumer Behaviour: Pearson Higher Education AU.

Somasundaran, T. N.,

& Light, C. D. (1991). A Cross-Cultural and

Media Specific Analysis of Student Attitudes Toward

Advertising. In Proceedings of the American Marketing

Association’s Educators' Conference, 2, 667-669.

Wang, Y. (2014). Consumers’ Purchase Intentions of Shoes: Theory of Planned behaviour and Desired Attributes. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 6(4). https://doi.org/10.5539/ijms.v6n4p50

Wicker, A. (1969). Attitudes Versus Actions: The Relationship of Verbal and Overt Behavioural Responses to Attitude Objects. Journal of social issues, 25(4), 41–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1969.tb00619.x

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.