ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

From Notches to Alphabet: Tracing the Evolution and Development of Scripts from Ancient to Modern World

Saini Barkha 1![]()

![]() ,

Dr Gurcharan Singh 2

,

Dr Gurcharan Singh 2![]()

![]() ,

Neetu Negi 1

,

Neetu Negi 1![]()

![]()

1 Research

Scholar, Department of Fine Arts, Kurukshetra University, India

2 Associate

Professor, Department of Fine Arts, Kurukshetra University, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Human

association that is societies necessitate communication and language is the

elemental means of human communication. In primitive times, communication was

generally done through oral means restricted by space and time. Writing

surpassed these limitations, allowing man to raise civilization. Writing

began at first in the form of noticeable signs or pictures understandable to

men. And now it has emerged in various ways: in science it is a scholarly

tool, in literature it is a cultural channel and in art it is a form in itself. This preliminary investigation of history of writing is intended to provide background

knowledge on the evolution of text as an art element. The present research

aspires to investigate the evolution and advancement of scripts from ancient

times to the emergence of alphabets. It provides the genesis, forms,

objectives and sequential changes of the world’s major scripts. In the first

section, what constitutes ‘complete writing’ has been defined with the

assistance of scholarly theories. A brief insight of pictography and

logography as prewriting has also been observed. Further in the second

section the advancements in pictorial writing to phonetic writing is outlined. The third section traces the stories of

Indian scripts and their development over the centuries. The study is based

on qualitative research method acquiring data from

museums, secondary sources and documentations. The research thus is an

attempt to explore the value and objectivity of text used as a visual

communication element. Eventually the study provides visualization of scripts

in the form of notches, tallies, pictographs, graphic symbols and complete

alphabets. |

|||

|

Received 31 October 2023 Accepted 23 July 2024 Published 31 July 2024 Corresponding Author Saini Barkha,

sainibarkha517@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v5.i2.2024.723 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2024 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Scripts, Knot Records, Tallies, Pictographs, Graphic

Symbols, Phonetization, Alphabet, Modern Scripts |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Development of Scripts in Ancient World – An Overview

A study

on the account of development of writing should be asserted with the awareness

of what represents ‘writing’. Exchange of human thoughts can be accomplished in

several ways, verbal communication or spoken language is one of them. And

writing is one of the forms to support human speech. Since we perceive writing

only for its contemporary use, it might be challenging to determine an

interpretation of all previous, immediate and approaching meanings. It will be

suitable to avoid the formal definition because writing would have, is and will

mean diverse in all the ages. Although it is satisfactory that writing is actually the arrangement of certain symbols that it may distinctly represent human language. According

to Fisher, “The three necessary components that define complete writing are: (i) Complete writing must have as its purpose communication.

(ii) Complete writing must consist of artificial graphic marks on a durable

electronic surface. (iii) Complete writing must use marks that relate

conventionally to articulate speech.” Fisher (2001), Coulmas (2003) In the theories of evolution of

complete writing many people are inclined towards divine provenance. This

narration remained alive in Europe till 1800s and up until now accepted in

various countries such as US, but many considered it as an outcome of joint

achievement or unintentional discovery. But there is definitely

no natural evolution in the development of scripts. Writing

system did not transform on their own, they were intentionally changed by

humans. Fisher (2001) Prior to complete writing, man used

to maintain information with the help of memory devices and graphic symbols

called ‘mnemonics’. One such repertory of universal

symbols is Rock art. It had anthropomorphs, flora and fauna, celestial bodies

and geometric designs. Similarly, mnemonics also served the linguistic context.

Knot records, notches, pictographs, tallies, indexical symbols etc. linked

physical objects with sound. Bühler (2023)

1.1.1. Knot Records

Knot

records date back to the Early Neolithic age and are thought out to be the

‘mnemonics’ of the ancient world. Birket-Smith (1967) These records were plain loops in an

individual or complex series of strings linked to higher order string. It was a

detailed and precise counting method. (see Figure 1) According to some scholars not

records was the only ancient writing form developed in

the Andes. Prem & Riese (1983) It is necessary to acknowledge that

knotted strings records do not include writing and are simple memory reminders.

Although its sole purpose is communication, they do not qualify

the standards of ‘complete writing’. Neither are they artificial marks on a

surface nor they have a conventional relation to

articulate speech.

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Knot Records Note Number of Knots

Represented Digits as Well as Values. |

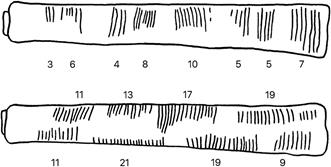

1.1.2. Notches

Similar to

knot records, notches were also mnemonics, used for the purpose of

communication but did not support speech or hearing. They are cut lines on

bones or bark of trees at regular intervals. As per some discoveries the cut

lines are intentional engravings. The Ishango Bone

discovered from Zaire suggest similar line scratches. (see

Figure 2) The cut marks on these artifacts

accord with lunar cycles, however these there are possibilities of additional

explanations. Tens of thousands of years ago, ancient men perhaps for some

reason was documenting something but again this was information storage and not

writing.

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 Ishango Bone from Zaire Note

Two

Sides of Ishango Bone Representing Grouped Notches.

|

1.1.3. Tallies and Indexical Symbols

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 Azilian Pebbles Note Some of

the Colored Designs on Pebbles from Azilian

Culture, Southern France, c.8000 BC, Source https://www.goldenageproject.org.uk/128azilianpebbles.php |

Tally

sticks can be regarded as an extension to notches. Tallies have long existed

parallel to complete writing. It was convenient for illiterates, time saving

and inexpensive than writing. Tallies were notches on wood that represented

numbers. This method traced a simple rule: the bigger the number, the more

amount of wood shall be incised in the tally stick. Though their purpose was to

convey message and record information; and also, they

were identified by marks on a durable surface, they did not articulate speech.

Indexical symbols also tracked a general principle: ten objects for ten sheep.

This system has been used for thousands of years by ancient men. According to

some discoveries, the finest and earliest example of pictographic writing was

found in Azilian culture of southern France in 8000

BC in the form of colored pebbles. (see Figure 3) Anyhow, the strips, circles, dots

and other designs on the pebble do not represent an identifiable natural phenomenon

and does not seem to articulate speech. Claiborne (1974)

1.1.4. Pictographs and Graphic Symbols

Knot

records, notches and tallies, all can be used for accountancy and prompts

memory but are incapable to display qualities and

characteristics. However, pictographs can, it is an

unintentional blend of marks and mnemonics. In several ways, the

Cave paintings are considered as a pictorial way of exchanging

information. Bahn & Vertut (1988) Pictographs can communicate a very

complex message but fails to put into words. However, unlike tallies, notches

and knot records, pictographs surely acknowledge phonetic values by using

particular objects and hence communicating their

spoken description. Hood (1968)

As

civilization advanced, the social needs such as administering goods, workers,

incomes, expenditures etc. required something radical and thus time-honored

mnemonics did not survive. Bernal (1971) Marking possession being a crucial

part of book-keeping perhaps gave birth to some of the world’s first graphic

symbols occurring on seals. Martin (1994) The Vinca culture (5300- 4300 BC)

in Romania holds numerous clay objects incised with symbols. (see Figure 4) A total of 210 symbols, out of

which 30 being main symbols were identified. Winn et al. (1981) In 1961, three clay tablets were

discovered at Tartaria, 20 kilometers east of Tordos. It is believed to be originally of the same Vinca

culture. (see Figure 5) According to the modern belief,

the earliest Balkan symbols seems to form a fancy or

symbolic inventory, that is they are neither logographs nor phonographs. However,

there are opinions for graphic symbols suggesting no relation to articulate

speech.

Figure 4

|

Figure 4 Incised Symbols from

Vinca Culture. Note Incised Symbols

on Pottery Found from the Vinca Settlement at Tordos,

5300- 4300 BC. source https://omniglot.com/writing/vinca.htm |

Figure 5

|

Figure 5 The Tartaria Tablets. Note The three baked

clay tablets discovered by archaeologist Nicolae Vlassa

at a Neolithic site in the village of Tartaria in

1961. |

1.1.5. Tokens

Tokens

are well chosen as the pre-eminent origin of complete writing. One token equal

one unit and therefore they directed to complete

writing. Numerous token artifacts dating from 8000- 1500 BC have been

discovered from Eastern Iran to Southern Turkey, Israel and ancient Sumer. Fisher (2001) The 4th millennium BC

brought an advancement; the clay tokens were confined within little play

envelopes called ‘Bullae’. These bullae were marked on their outside which

suggested the amount of particular commodity without

breaking them. These series of actions were acknowledged to be the origin of

perfect writing in 1930s. Schmandt-Besserat

(1981) Archaeologist Denise Schmangt-Besserat, who is a noted exponent of these

hypothesis compares the token with the first stylized Sumerian cuneiform. She

also claimed the non-pictographic cuneiform to be in fact derived from bullae

impressions. (see Figure 6)

Figure 6

|

Figure 6 From Tokens to Pictographs. Note The Figure

Represents the Possibility of Mesopotamian Cuneiform Signs Being Derived from

an Earlier Token or Bullae Impressions. Source

https://www.usu.edu/markdamen/1320hist&civ/chapters/16TOKENS.htm |

2. Evolution of Complete Writing: From Phonetization to Alphabets

According

to linguist Florian Coulmas- “The decisive step in

the development of writing is phonetization.” Coulmas (2003) Moreover, a person reading a sheep

pictogram would have resonated out ‘sheep’ on recognizing the token’s form. And

thus, phonetization is also not a complete writing.

Additional improvement was required and it was fixed

by systemic phoneticism. Systemic phoneticism

is coordinating symbols and their sounds in order to

compose a sign of a writing system. This systemic phonetic key was perhaps

inspired by the traits of Sumerian language and seems to have developed around

3200 BC. This transition inflated writing abilities exponentially and

stimulated immediate adaptations in various parts of the world. The ‘Rebus

principle’ is still believed to be the means of progression from pictography to

perfect writing by numerous scholars. Jensen (1969)

2.1. Mesopotamian Script (Cuneiform writing)

The

evolution from knot records to scripts proclaims that accounting is a precise

reason for the development of writing. Writing being

solely adopted for counting advanced when the Sumerian’s interest for the

afterlife gave rise to writings for funerary inscriptions. Around 3000 BC, a noteworthy

evolution of Mesopotamian writing was the concept of phonetic signs. Each and every further writing system and script occur to be

the descendants of this particular initial thought of systemic phoneticism. The best example of entire phoneticism

and the first text that did not deal with counting commodities, are the

inscriptions on vessels and seals stored in Royal Cemetery of Ur, dating 2700-

2600 BC. Schmandt-Besserat

(1981) Later in 2600- 2500 BC, the

Sumerian scripts became complicated with mixed ideograms and phonetic signs. Writing

was now being modelled for spoken language with the help of syllabary (system

of phonetic signs expressing syllables). A collection accompanying

of 400 signs, developed a script that was capable of

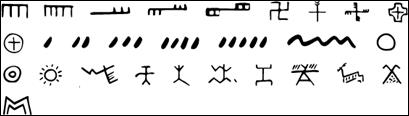

articulating any topic of human endeavor. (see Figure 7) This cuneiform writing was steady

until next 600 years and eventually about 15 languages were using cuneiform

inspired characters. Clayton (2019) The word ‘Cuneiform’ is derived

from Latin word ‘Cuneus’ which means ‘Wedge’ and ‘form’ meaning shape. The history of Cuneiform traces the evolution

of sound-writing from word-writing, with sound superseding iconicity entirely.

Sumerian writing which is recognized as the world’s

earliest complete writing emerged as a response to commercial demands.

Cuneiform writing largely appeared in clay, stone carvings, and inscriptions on

metal, glass, wax and ivory. Nearby 2500 BC, the Cuneiform script was outright and

can efficiently convey all sort of ideas and understanding. (see Figure 8)

Figure 7

|

Figure 7 Cuneiform Writing. Note The Figure

Displays the Origin and Advancement of Cuneiform Signs from 3500 to 500 BC. Source

https://www.theshorterword.com/cuneiform |

Figure 8

|

Figure 8 Sumerian Clay Tablet. Note This Ancient

Sumerian Clay Tablet that is Inscribed with Cuneiform Characters, Record the Distribution

of Barley and Wheat. c. 3000 BC. In Collection- Metropolitan Museum, New York.

Source https://kids.britannica.com/students/article/cuneiform-writing/273879/media |

2.2. Egyptian Script

The

following phase in the progression of Mesopotamian script expressed through

phonetic signs spread out of Sumer to adjoining regions. Besides the idea of

writing, Egyptians borrowed phonography, logography and linear sequencing from

Sumerians. With the help of phonetic values, the Egyptian signs were easily

codified. Ray (1986) El-Khawy

in Egypt reviews large scale incised ceremonial in the form of rock art which

seems to date around 3500 BC. Clayton (2019) They display characteristics of

early Hieroglyphic forms. From 3200 BC onwards, these hieroglyphs surfaced as

labels on small ivory tablets in tombs and ritual surfaces used to grind

cosmetics. One such example is the Palette of Narmer. The hieroglyphs

identified on it are the names and titles of the Pharaoh, his attendees and the

enamored rivals. Egypt initiated writing in ink using pens and read brushes and

Greek recognized this writing as ‘hieratic’. Thus, the Egyptians had two main

objectives for writing: first was for ritual purposes that used presentable

script carved in metal or stone and second was ink written used for royal

administrations. Gradually, the writing of Egypt matured in four unique but

correlated scripts: Hieroglyphic, Hieratic, Demotic and Coptic. Ritner (1996) These scripts only differed in appearance but their function and form were similar.

Hieroglyphic writing initially consisted about 2500

sign out of which 500 signs were in regular use. Islamic Heritage of India.

(1981)

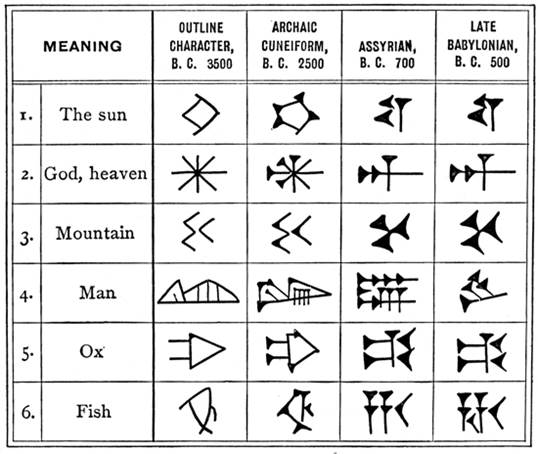

Apparently

the most phenomenal innovation of the scribes from Egypt was the constant use

of 26 uni-consonantal signs, each carrying separate

consonants. Although, this set of 26 signs didn’t have vowels, it was considered to be the world’s first alphabet. It was from

this Egyptian writing that an alphabet evolved later, around 1850 BC. Though

the concept of writing may have appeared in Sumer, the method of writing and

letters are descendants of ancient Egypt. (see Figure 9)

Figure 9

|

Figure 9 Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs to Present Day Latin

Alphabet. Source Fisher (2001). A History of Writing. Reaktion Books |

2.3. Scripts of China and Mesoamerica

In China the

earliest instances of writing originated in a tributary of Yellow

river in Beijing and the earliest scripts probably of late Shang dynasty (1300-

1050 BC) were found on fragments of animal bones. In 1899, scholar Wang Yirong identified characters carved on these bones also

known as Oracle bones. Clayton (2019) Oracle bone inscriptions are called

‘Koukotsubun’ which translates to ‘text on shells and

bones.’ (see Figure 10) These bone inscriptions extended

Chinese linguistic and historical knowledge. The engravings recorded several

questions regarding crop rotation, childbirth, warfare etc. About 4500 varied

symbols were found, out of which some remain undeciphered, some evolved in

terms of form and function and many of these characters identified are still in

use today. Chinese characters were capable of expressing

both concepts and sounds of spoken language.

Figure 10

|

Figure 10 Oracle Bone Inscription. Note Oracle

Bone with Incised Script Found on Tortoise Shell, 13th Century BC. Source https://beyond-calligraphy.com/2010/03/05/oracle-bone-script/ |

Figure 11

|

Figure 11 Mayan Script. Note Mayan Script from Tikal,

Guatemala. c. 700 AD. Source Fisher (2001). A History of Writing. Reaktion Books. |

Ancient Mesoamerica had several writing systems, the only

true pre-Columbian writing. Mayan hieroglyphics writing is logographic, which

means - an entire word is represented by a letter, symbol or sign. The Maya

people of Mesoamerica used this writing up till the end of 17th

century. These inscriptions can be seen on standing stone slabs called

‘stelae’, on stone lintels, pottery, sculptures and on Mayan books, only a few

of which have survived. (see Figure 11) The Mayan

writing order involves about 800 characters, combining phonetic signs that

represent syllables and hieroglyphs. Till the middle of the 20th

century, only symbols depicting dates and numbers, rulers’ name and their

associated events such as births, deaths and victories could be deciphered in

the Mayan writing. A large number of scholars believed

the Mayan writing to be completely logographic, which means an entire word

could be represented by a single glyph.

Moreover, Mayan inscription was widely proclaimed as religious in

character. Britannica (2007)

2.4. The Alphabet and Modern Scripts

Around

1500 BC in the ancient Near East, alphabet was

introduced which is marked as the third phase in the evolution of writing.

Limited sounds of any language were a benefit for the alphabets of Proto-Sinaitic

and Proto-Canaanite, that developed in present day Lebanon. This writing system

comprised of 22 letters, each representing a particular

sound. These letters united in innumerable ways and paved a

way for the original transcribing speech. Powell (1996) This recent alphabet was totally

divergent from prior syllabaries and had an acrophony. Further, the consonantal

alphabetic system travelled to Greece with the merchants of Lebanon, probably

around 800 BC. The Semitic alphabet was now complete by adding vowels that is

a, e, i, o, u. And thus the 27 letter Greek alphabet

enhanced the speech transcription and this system did

not undergo any fundamental change further.

3. Origination and Development of Indian Scripts: An Overview

In India

the earliest script was of Indus valley civilization that owned logo-graphic or

word picture writing in the 3rd- 2nd millennium BC. Following with an extended gap of over 1000 years, an

alphabetic writing noted as Brahmi script emerges in 3rd century BC.

The invention of writing was highly valued and was often attributed to

divinities and folk heroes. The Indian Brahmi script is associated with Brahma

and was evolved to write the Vedic literature which

was earlier handed down orally in Guru-shishya tradition. The Brahmi script is

regarded as the parent of all Indian scripts. The story of these scripts and

their development over the centuries is defined in the following subsection. Kalyanaraman (2010)

3.1. Indus Valley Script

Following

the earliest pictographic and petroglyph representations, the first evidence of

writing can be noticed in the Indus valley civilization. After the discovery of

this extensive civilization which is regarded as the first urban culture of

South Asia, scholars suggest that the Indian script is established around 2500

BC. Parpola (1994) Considering the fact that the Indus

writing system has not been deciphered yet, it uses remains unknown. Indus

valley script was probably used from 3500 to 1200 BC. It remained abandoned for

almost four thousand years until it was discovered by European archaeologists in

1870s. The early evidence of writing found from Indus valley civilization and

in Harappan cultures of eastern Baluchistan (3500 BC) is believed to proceed

phonetic signs of Egypt and Samaria. (c. 3200 BC). This earliest Indus valley

writing is evident on pottery as ownership marks. Around 2600 BC, known as the

period of ‘cultural unification’ a systematic and

broadly recognized Indus valley script emerged. It occurs on the seals or seal

impression of Harappan period. The seal inscriptions are extremely short, making

it suspicious to symbolize a writing system. (see Figure 12) The Indus writing characters are

mostly pictorial and consist 400 to 500 signs. The

signs are believed to have been written from left to right because various

instances of the signs compressed on left side suggest the lack of space at the

end of the row. Rahman (n.d.)

Figure 12

|

Figure 12 Seal Inscriptions from Indus Valley Civilization. 2500- 2000 BC. Source Fisher (2001). A History of Writing. Reaktion Books. |

Considering

the large number of signs, the Indus script is believed to be logo-syllabic. It

is also assumed that the script was used as an administrative tool for trade

purposes. Contemporary studies on seal inscriptions made scholar

believe that the language or script neither belongs to Indo European family,

nor it is influenced by Sumerians or Elamites. It has probably developed from

rock art of India. Thus, the script of Indus valley civilization evolved and

matured in isolation, inspiring no other writing system. Rajgor (2000)

3.2. The Indic Scripts of India

The writing

system of Indus valley remained inactive and dead for thousand years leaving no

descendants and writing did not initiate until 8th century BC in the

Indian subcontinent. But as soon as writing flourished, India displayed world’s

most elegant and assorted scholarly customs. Coulmas (2003) Apart from being just a speech

recording tool, Indian writing is the emblem of social franchise. The history

of Indian script is stuck amidst many conflicting theories. The folklore of

India honors Ganesha (Lord of wisdom) as the inventor of writing. On the other

hand, scholars believe that writing in the Indian subcontinent probably derived

from Aramaic script. Although there are several evidence of earlier Indian

writing, the famous Ashokan edicts from c. 253 to 250 BC are

considered to be the first longest documents. The edicts were inscribed

in both Indian scripts - Kharosthi and Brahmi.

1)

The Kharosthi script: The Kharosthi script developed out of the Aramaic script, which

belongs to the Semitic group of scripts and was derived from the Phoenician

script. The derivation of Kharosthi from Aramaic had already been suggested in

the mid-19th century and was finally demonstrated in 1895 by Georg

Buhler, one of the greatest names in Indian paleography. Kharosthi script is

alone among Indic scripts that is written from right to left. This script

remained predominant in Gandhar until the 3rd or 4th

century CE. From the 2nd century CE onward, the Gandharian

region was ruled by non-Indian dynasties- Indo-Greek, Scythian, Parthian and Kusana, as a result of the

expansion of these kingdoms the Kharosthi script spread from Gandhar to the

northwest, South and Northeast of Asia. In northern India Kharosthi flourished

especially in and around the city of Mathura, a major administrative center of

the Scytho-Parthian and Kusana

kings. A number of inscriptions in Kharosthi mainly on

stone and of Buddhist affiliation have been found in and around Mathura.

Kharosthi was also widely used in South Asia in the coin legends of the

Indo-Greek and Scythian rulers usually in combination with Brahmi or Greek

(sometimes all the three scripts are used on the same coin). (see Figure 13) This script fell out of use during

the 3rd or at the latest the 4th century CE. The decline

of the Kharosthi script in South Asia was probably determined by the fall of

the Kushan empire and by the subsequent geographical shift of the center of

political power towards northern and northeastern India, where Brahmi was in

use. Thus, in contrast to Brahmi, the Kharosthi script died out without any

descendants.

Figure 13

|

Figure 13 Coins Belonging to Kusana Empire. Note Four Gold Coins

of the Kusana Emperor Vima Kadphises,

(Obverse in Greek, Reverse in Kharosthi) 2nd Century CE. Source

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Four_sets_of_Gold_Coins_of_Vima_Kadphises.jpg |

2)

The Brahmi Script: In contrast with Kharosthi, the origin of the Brahmi script is still

debated. Since the last decades of the 19th century a wide range of hypothesis have been put forward by scholars. This

hypothesis can be divided into two broad categories: first those proposing an

indigenous (Indian) origin of the Brahmi script which would have derived from

the Indus valley script or invented from scratch in Ashok’s time or just before

it, second those assuming that Brahmi derived from a

non-Indian prototype -Greek together with Kharosthi or a later north semitic

script that is the Aramaic script. Brahmi is marked as the originator of most

Indian scripts. It originated around 8th or

7th century BC and was first defined by James Prinsep in 1838. Evolution of Script in India. Journals of India. (2018) Brahmi script is usually written

from left to right, as it is evident from Ashokan inscriptions, although the

earliest inscriptions are written right to left similar to

Semitic scripts. (see Figure 14) Approximately 2000 years ago,

Brahmi script developed into two main script families- North Indian and South

Indian, each consisting various scripts. The northern script was more angular

and southern script being more circular. Both families share the original

Brahmi principles of consonantal signs with required diacritics that suggest

walls and differ only externally. Another significant north Indian script that

flourished in 4th century AD is Gupta script, also known as the late

Brahmi script or Brahmi’s first main daughter. After the decline of Mauryan

empire (3rd century BC) and up to the end of Gupta empire (early 6th

century CE) the Brahmi script went through new stages of development named

after the ruling dynasties of the time: Sunga Brahmi, Kusana

Brahmi and Gupta Brahmi. Further in the coming centuries after the collapse of

the Gupta empire the process of regional differentiation of the Indic scripts

was favored by political fragmentation, to the point that distinct local

derivatives of the Brahmi became discernible.

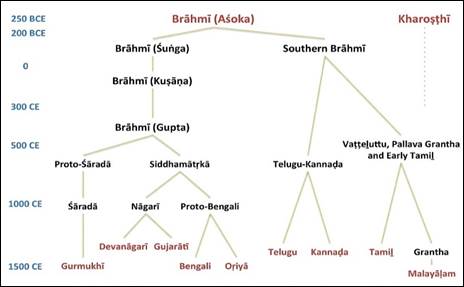

Figure 14

|

Figure 14 Edicts of Ashoka. Note This Ashokan Edict is a Metal

Cast of Inscribed Rock at Girnar, Gujarat. 3rd Century

BC. Source National Museum, Delhi. |

The major

regional scripts that evolved from Gupta Brahmi are: Proto-Sarada- in the far

northwest of the subcontinent (Kashmir). This is an isolated variety of the

Gupta Brahmi script, Siddhamatrka- in the north and

Northeast but also in the West (present day Maharashtra) and occasionally even

in the deccan and the far South. Being the parent script of the Devanagari as

well as of the northeastern scripts, Siddhamatrka

delivered an important role in the history of Indic scripts. Proto

Telugu-Kannada- in upper southern India. Grantha,

Tamil and Vatteluttu in the South of the Indian

peninsula. (see Figure 15) The Gupta alphabets emerged as the

ancestor of Indic scripts and influenced the valuable scripts such as Sarada,

Nagari, Pali and Tibetan. Evolving around 633 AD and later developing fully in

the 11th century, Nagari script became ‘Devanagari’. Devanagari was the main

vehicle for Sanskrit literature and with time it became India's principal

script. It conveyed several languages such as Hindi, Nepali, Marwari, Kumaoni and other non-Indian Aryan languages. Later it also

became the parent of Gurumukhi script, which was detailed in 1500s to write

Punjabi language. Another important north Indian script derived from Nagari is

Proto-Bengali, that further conveyed many significant languages such as

Bengali, Assamese, Manipuri, Maithili and Santhali.

Further Sarada and Pali scripts, daughter of Gupta script gave rise to many

scripts and were specifically elaborated to write Prakrit languages. Pali

script grew with the expansion of Buddhism. The southern Indian scripts

primarily convey their native Dravidian language which consists of Tamil,

Telugu, Malayalam, Kannada and others. To sum up, it seems that Indians according

to their phonological principles, purposely redesigned their scripts, referring

the Semitic script.

Figure 15

|

Figure 15 Tree Diagram of the Important Indic Scripts. |

3.3. Comparative Analysis: Indian and Western Scripts

1)

Origins and Development: Indian scripts have evolved from

the ancient Brahmi script, dating back to at least the 3rd century BCE. The

Brahmi script itself is believed to have been influenced by Aramaic and

Kharosthi scripts. The key Indian scripts include Devanagari, Tamil, Telugu,

Kannada, Bengali, and many others, each developed from regional variations of

Brahmi. Whereas Western scripts primarily evolved from the ancient Phoenician

script, which dates back to around 1200 BCE. The Greek

script developed from Phoenician, and subsequently, the Roman (Latin) script

evolved from Greek. The Latin script is the most widespread, forming the basis

of most Western European languages.

2)

Cultural and Linguistic Diversity: The diversity of languages in India led to the evolution of numerous

scripts to cater to different languages. Scripts like Devanagari became

standardized for multiple languages (e.g., Hindi, Marathi, Sanskrit), while

others like Tamil remained specific to their language.

3)

Religious Influence: The spread of Buddhism and

Hinduism played a significant role in the dissemination and adaptation of

scripts across Asia. The scripts often carried religious texts and were used in

inscriptions and manuscripts, influencing regions beyond the Indian subcontinent.

4)

Alphabetic System: Western scripts, particularly the

Latin script, utilize an alphabetic system where each letter represents a

sound. The Greek and Latin alphabets influenced the development of other

European scripts, including Cyrillic.

5)

Standardization and Printing: The invention

of the printing press in the 15th century by Johannes Gutenberg significantly

standardized the Latin script. The Renaissance and subsequent periods

emphasized the standardization and reform of orthography in Western languages.

4. Structural and Functional Characteristics

Similarities: Both Indian and Western scripts are phonetic to varying degrees. Letters

or characters represent sounds or combinations of sounds. The systems

have shown remarkable adaptability, evolving to accommodate new languages and

technological advancements. Both have rich literary traditions, with

extensive bodies of literature in classical and modern languages.

Differences: Indian scripts are often more complex, with characters representing

consonant-vowel combinations, and the use of diacritics to modify sounds.

Whereas Western scripts, particularly Latin, use a simpler alphabetic system

with separate vowels and consonants. Indian scripts are typically

abugidas (each consonant has an inherent vowel sound that can be altered with

diacritics). And Western scripts, like the Latin script, are true

alphabets with distinct letters for each vowel and consonant sound. If

we consider the visual form, Indian scripts are often more intricate and

visually complex, with rounded forms and connected characters (e.g.,

Devanagari's horizontal line on top of words). Western scripts tend to

have more distinct, separate letters, making them more straightforward in their

visual form.

If we compare the evolutionary pathways, we see

that the evolution of Indian scripts was heavily influenced by regional,

cultural, and linguistic diversity, leading to the development of distinct

scripts for different languages. The need to transcribe religious and

philosophical texts played a crucial role in the script's evolution and

standardization. Modern technology has necessitated the digitization and

encoding of Indian scripts, leading to the development of Unicode standards.

In case of Western scripts, the influence of Classical Languages such as

Latin and Greek provided a strong foundation, influencing the development of

scripts across Europe. The spread of Western scripts was accelerated by

colonial expansion, trade, and globalization. The printing press,

typewriters, and digital technology have all played significant roles in the

evolution and standardization of Western scripts.

Thus, the evolution of Indian and Western

scripts highlights both their unique trajectories and shared characteristics.

Indian scripts evolved in a culturally diverse and linguistically rich

environment, resulting in a variety of complex writing systems. In contrast,

Western scripts followed a more unified path influenced by the spread of Greek

and Latin, leading to widespread standardization and adoption. Despite these

differences, both traditions share a commitment to phonetic representation,

adaptability, and a profound impact on literature and communication.

5. Conclusion

Since the evolution and development of languages and script, every generation has been fascinated and embraced the wonder of writing. It proved to be a society’s most accomplished, adaptable and functional tool. Thanks to the scribes who developed the concept of complete writing after several years of incomplete writing using knot records, notches, tokens and other graphic symbols on various surfaces. Around 4000 – 3500 BC, different forms of systemic phoneticism that explains complete writing, possibly appeared in Mesopotamia. At the hand of stimulus diffusion, that is – the scattering of an idea or practices from one place to another; the functions and capability of writing inspired neighbors to construct their own script and writing system. But remarkably, all over the history we find only three main writing traditions: Afro-Asiatic, Asian and American. And perhaps they all share one Sumerian origin. Further, the three main writing systems that dominated were – a. ‘logography’ also called as word-writing, in which the writing signs or a minimal unit represents words, b. ‘syllabography, also called syllable-writing, in which the graphemes express individual syllables and c. ‘alphabet’ in which signs called letter stands for an individual consonant and vowel. Each generation and society maximized these three writing systems based on their languages. These three writing systems are neither the classification nor levels in the evolution of writing. They are merely distinct forms that serves diverse linguistic and social needs of a society. The one lesson that is clearly learned from this study of history of writing is that writing did not emerge from mute pictures. Instead, it came out to be the graphic expression of actual speech. However, this thought seems to be changing now. According to modern studies, the reading sequence of written letters or words, directly gets linked to thoughts and entirely escapes the speech.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Bahn, P. G., & Vertut, J. (1988). Images of the Ice. Age. Leicester: Windward.

Bernal, J. D. (1971). Science in History, Volume 4: The Social Sciences: A Conclusion. MIT Press Books, 1.

Birket-Smith, K. (1967). The Circumpacific Distribution of Knot Records.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2007, February 21). Mayan Hieroglyphic Writing. Encyclopedia Britannica.

Bühler, G. (2023). On the Origin of the Indian Brahma Alphabet. (n.p.): Creative Media Partners, LLC.

Claiborne, R. (1974). The Birth of Writing.

Clayton, E. (2019). The Evolution of the Alphabet. The British Library Website.

Coulmas, F. (2003). Writing Systems: An Introduction to their Linguistic Analysis. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139164597

Evolution of Script in India. Journals of India. (2018).

Fisher, S. R. (2001). A History of Writing. Reaktion Books.

Hood, M. S. F. (1968). The Tartaria Tablets. Scientific American, 218(5), 30-37. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0568-30

Islamic Heritage of India. (1981). National Museum, Delhi.

Jensen, H. (1969). Sign, Symbol, and Script: An Account of Man's Efforts to Write. Putnam.

Kalyanaraman, S. (2010). Indus Script Cipher: Hieroglyphs of Indian Linguistic Area. India: Sarasvati Research Centre.

Martin, H. J. (1994). The History and Power of Writing. University of Chicago Press.

Parpola, A. H. S. (1994). Deciphering the Indus Script. Cambridge University Press.

Powell, B. B. (1996). Homer and the Origin of the Greek Alphabet. Cambridge University Press.

Prem, H. J., & Riese, B. (1983). Autochthonous American Writing Systems: The Aztec and Maya Examples. Writing in Focus, 167-186. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110822830.167

Rahman, K. (n.d.). Evolution of Scripts in Arabic Calligraphy. National Museum, Delhi.

Rajgor, D. (2000). Palaeolinguistic Profile of Brāhmī Script. India: Pratibha Prakashan.

Ray, J. D. (1986). The Emergence of Writing in Egypt. World Archaeology, 17(3), 307-316. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.1986.9979972

Ritner, R. K. (1996). Egyptian Writing. Daniels & Bright (eds.), 73-87.

Schmandt-Besserat, D. (1981). From Tokens to Tablets: A Re-evaluation of the So-Called" Numerical Tablets". Visible Language, 15(4), 321-344.

Winn, S. M., Markotic, V., & Hromadiuk, B. (1981). Pre-Writing in Southeastern Europe: The Sign System of the Vinca Culture, ca. 4000 BC. Calgary: Western Publishers.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.