ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

BEYOND THE OFFICIAL PHOTOGRAPH: COMPARATIVE STUDY OF MEDIA AND PARTY PORTRAITS OF INDIAN WOMEN POLITICIANS

Lubna Sadaf Naqvi 1![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Bikashdev Chhura 2

,

Dr. Bikashdev Chhura 2![]()

![]() ,

Aarti Sharma 3

,

Aarti Sharma 3![]() , Dr. Bhavana Sharma 4

, Dr. Bhavana Sharma 4![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Sumit Agarwala 5

,

Dr. Sumit Agarwala 5![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Amit Verma 6

,

Dr. Amit Verma 6![]()

![]()

1 Ph.D.,

Research Scholar, Department of Political Science and Public Administration,

School of Humanities and Social Science, Nims University Rajasthan, Jaipur-

303121, India

2 Assistant

Professor and Head, Department of Political Science and Public Administration,

School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Nims University Rajasthan,

Jaipur-303121, India

3 Research

Scholar, Ganpat University, Mehsana, Gujarat, India

4 Professor

of Law, The Assam Royal Global University, Guwahati, Assam, India

5 Associate

Professor, Royal School of Law and Administration, Assam, India

6 Associate

Professor and Assistant Registrar (Helpdesk), Journalism and Mass

Communication, Centre for Distance and Online Education, Manipal University

Jaipur, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

In modern

democracies, political portraits are quite important in the development of

the perception of the populace regarding leadership, legitimacy and gender.

This paper analyzes the visual representation of Indian women politicians

under three types of regimes, namely, official, party, and media, which are

ruled by various institutional, ideological and journalistic logics. Going

beyond the analysis of isolated images, the study uses the comparative

framework including the visual content coding, the regime-based analysis, and

the evaluation based on the case studies. A data collection of publicly

available portraits was collected through a structured coding scheme that

comprises of setting, pose, affect, symbolism, textual elements, and

personalization. The results indicate systematic differences at the regime

level: institutional power and disinterest are highlighted in official

portraits, ideological symbolism and collective identity are in the

foreground of party portraits, and personalization, dramatization, and

emotional expressiveness are prioritized in media portraits. Cases allow also revealing that

identical political players are graphically re-created even between regimes, and reveal a stable trade-off between power and

personalization. This research is important to visual politics and gender

studies by providing a regime-specific approach of analyzing how political

imagery reproduces negotiation of gendered leadership stories. The findings

highlight the importance of considering visual analysis as a unified part of

political communication studies and have a base to conduct cross-national,

longitudinal, and computational research of political representation. |

|||

|

Received 07 November 2025 Accepted 12 December 2025 Published 31 January 2026 Corresponding Author Dr.

Bhavana Sharma, sharmabhavana44@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v7.i1.2026.7044 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2026 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Visual Politics, Women Politicians, Political

Portraits, Media Framing, Party Communication, Gendered Representation,

Political Imagery |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

In modern democracies, political communication is becoming more visual, where images have a final say on the perception of the masses, credibility, and legitimacy of the political actors. Such pictures include official photographs, portraits created by the party and the representation of this club in the media, which are separate visual regimes (with another logic, intention, and expectations of the audience) Bhowmick (2024). To women in political positions in India, the regimes of imagery are especially significant, given that imagery representation comes in the interplay of established gender norms, cultural expectations and institutional power arrangements Saranya et al. (2024). Although an official portraiture is supposed to convey a sense of neutrality, authority and continuity in an organization, a party portraiture should focus on ideological fit, mobilization discourse, and symbolic affiliation to leadership. The portraits of the media are, on the other hand, more immediate, emotional, and newsworthy and often exaggerated gestures, expressions, and moments of conflict or charisma Williams (2020). The expanding literature on political communication in relation to gender representation, the systematic visual comparison of the representation of the same type of political actors, i.e. Indian women politicians in these regimes, are scarce. There is a paucity of literature addressing visual strategies or styles within political imagery, as current literature resorts to either a textual discourse or electoral messaging, and neglects the visual strategies within the political imagery Zaiats et al. (2024). This is especially a weak spot in the Indian context where visual politics and party symbolism is fully embedded in mass mobilization and mediated spectacle of election cycles. Female politicians are in a strange landscape of visual imagery where the demands of power are alongside demands of being attractive, familiar, or ethically upright.

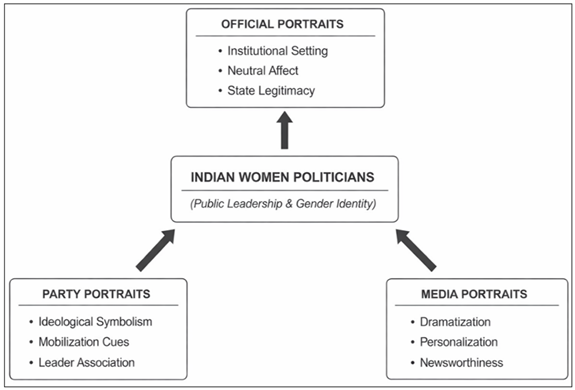

Figure 1

Figure 1 Conceptual Framework of Portraits Regimes for Indian

Women Politicians

This paper presents the political portraits not only as the aesthetical products but as the strategic visual images which encode power, gender and ideology. Going beyond the official photograph and directly juxtaposing it with party and media portraits, the paper will attempt to understand how a visual indicator, including setting, pose, affect, symbolism and overlay of a written text, will differ systematically across regimes Courtney et al. (2020), Galy-Badenas and Gray (2020). These differences carry with them the consequences of construction and interpretation of leadership, competence and legitimacy of women politicians as depicted in Figure 1. Based on this, the main aim of this study is to carry out a comparative aesthetic examination of official, party, as well as media portraits of Indian women politicians in light of a synthetic technology that incorporates visual contents examination and methodical comparative analysis Gogoi and Bordoloi (2024). The research is significant to the literature of visual politics and gender in the sense that it provides an empirically-based systematic framework through which to appreciate the role of political imagery in producing, supporting, or confronting gendered narratives in commonplace political representation.

2. Literature Review

Visual communication has since assumed a pivotal role in modern political behavior, whereby images now have a major influence in the ways in which political players are perceived, analyzed, and recollected by the citizens Ajani et al. (2025). The political communication scholars suggest that images are not only the complements of the textual discourse but also independent units of meaning-making which are able to compress the authority, ideology, and emotion into one frame Klanjšek (n.d.). Political portraits have a conclusive role in creating credibility, legitimacy, and even leaders identity especially in democratic systems where trust is perpetually negotiated by way of representation Liu et al. (2020). Quite a significant amount of literature has been devoted to the gender representation in the political sphere, demonstrating that women politicians continue to be subjected to different representational standards than men. The literature on media systems shows that female heads are frequently positioned at the border of strengths and likeability with excessive focus in visual depiction on looks, manner and emotional states Magdum and Bhattacharya (2021). Instead of being represented as independent decision-makers, women politicians are often represented in the relationship and thus, through their association with family roles, senior men leaders, or symbolism to the point of doing morally upright things hence redefining the concept of power and competence subtly Ministry of Panchayat Raj (2019). These visual patterns are so upper-grounded in cultural demands and forms of journalism that they enforce gendered discourse even when the formal political equality is involved. In order to bring together these fractured pieces of scholarship, Table 1 is a summary of the prevailing thematic themes, visual focus and constraints that have been revealed in previous studies about political imagery and gender imagery.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary of Prior Research on Visual Representation and Gender in Political Communication |

||||

|

Thematic Area |

Focus of Existing Studies |

Key Visual Emphasis |

Major Findings |

Identified Limitations |

|

Visual Politics in Democratic

Communication |

Role of images in shaping political

legitimacy and public perception |

Authority cues, symbolism, visual

framing |

Political images function as autonomous

meaning-making tools influencing trust and credibility |

Limited attention to gender-specific

analysis |

|

Gendered Representation in Political

Media |

Differential portrayal of women vs men

politicians |

Appearance, affect, relational

positioning |

Women leaders are framed along

authority–approachability tension |

Predominantly media-centric approaches |

|

Official Political Portraiture |

Institutional and state-sponsored

imagery |

Neutrality, formality, standardized

settings |

Emphasis on legitimacy and continuity |

Treated in isolation from party and

media visuals |

|

Party-Driven Political Imagery |

Visual branding and ideological signaling |

Party symbols, slogans, leader

association |

Individuals embedded within collective

identity |

Gender dynamics often underexplored |

|

Media Framing of Political Actors |

News values in image selection |

Dramatization, personalization,

emotional moments |

Amplification of conflict and

individuality |

Rarely compared with official or party

imagery |

|

Indian Context of Visual Politics |

Election campaigns and mediated

spectacle |

Symbolism, mass mobilization visuals |

Visual strategies central to Indian

political communication |

Scarcity of gender-focused comparative

portrait studies |

As can be seen in Table 1, the prevailing scholarship has yielded worthwhile pieces of information in terms of individual areas of political imagery, although the investigation is conducted rather aversely, in isolated terms. There has also been an evident absence of comparative research, which undertakes an integrated approach to examine the role of official, party, and media portraits in the development of the visual imago of women politicians, particularly basing on the Indian political scene Mishra (2015). This gap being bridged, the current paper unites these strands in a systematic comparison of the regimes of portraits, allowing to gain in a more holistic and gender-specific picture of visual political representation. The studies on official political portraiture highlight that the importance of institutional imagery helps to propose a sense of neutrality, continuity and legitimacy to the state. There are usually very strict rules regulating official portraits, such as restrained expressions, official outfits, plain backgrounds, which reduce individuality to the benefit of institutional power Ono and Endo (2024), Reshma and Manjula (2024). Visual items that include logos, slogans, colors and closeness to top leadership are often combined in party portraits in order to entrench individual politicians to a shared political identity Saville et al. (2024). These images have loyalty, alignment and mass appeal at their top priority and not institutional restraint, particularly in campaign seasons. A further study into media framing of political actors finds that patterns of news images selection are under the guidelines of news values of conflict, dramatization, personalization, and immediacy Snipes and Mudde (2020). Media portraits often focus on musical gestures, emotionally intense scenes, or picturesque scenes, which have added to personal portrayals that have been individualized and (in some cases) sensationalized. This increased personalization as a woman politician usually leads to increased examination of facial expression and behavior, which strengthens the story of emotionality or exceptionality.

3. Conceptual Framework and Research Questions

Developing the perspectives of visual communication, gender studies, and literature on political branding, the framework assumes that the portraits of women politicians are based on three different though interrelated regimes the official, party and media one, each of which features its own production logic, its orientation to the audience and its norms at representation. These regimes do not only vary aesthetically; they encode different definitions of power, authority and models of leadership that define the meaning of authority to the people. With Indian women politicians taking centre stage in this framework as shown in Figure 1, the intersection of public leadership and gender identity is achieved.

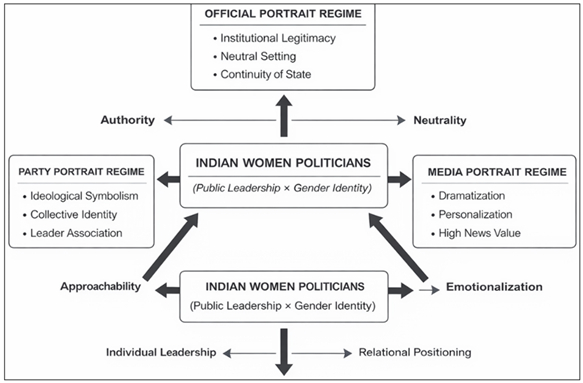

Figure 2

Figure 2 Conceptual Framework of Portrait Regimes and Gendered Visual Dimensions

Formal portraits are the symbol of the institutional regime, in which the neutrality, formality, and the continuity of the state are valued. Similar visual effects like restrained emotion, normalized context and lack of figurativeness are used in order to downplay personality and prefigure institutional power. On the contrary, party portraits are a mobilizing regime where ideological orientation and group identity are graphically highlighted Sultania (2024). These portraits are often including party symbols, slogans, color and visual association with top leadership and place women politicians in a larger ideological context instead of individual actors as shown in Figure 2. Journalism norms and platform-based dynamics construct the media image regime. Dramatization, personalizing, and emotional salience are positioned at the top of the agenda of media portraits in this way newsworthiness is prioritized. Gestures are often expressive, framing is often close, visuals are often in high contrast, text is often extruded over the image and these add to a stronger emphasis on individuality and immediacy. In the case of female politicians, the addition of gendered interpretations using foregrounding of affect and demeanor often impacts the issue of perceiving leadership competence and credibility in the way that leadership competence and credibility can be politicized as being affective and demeanor Van der Pas and Aaldering (2020). The study follows this framework and answers the following research questions:

· RQ1: How do visual cues associated with authority and institutional legitimacy differ across official, party, and media portraits of Indian women politicians?

· RQ2: To what extent do party portraits emphasize collective identity and ideological symbolism compared to official and media portraits?

· RQ3: How does the level of dramatization and personalization vary between media portraits and the other portrait regimes?

· RQ4: What gendered visual patterns emerge across portrait regimes, particularly in relation to affect, relational positioning, and leadership representation?

The conceptual frame also incorporates dimensions of gendered visual framing, including that of authority versus approachability, neutrality versus emotionalization, and individual leadership versus relational positioning as cross-cutting axes that exist on all three axes. Instead of making a consideration of uniform representation, the framework predicts a systematic difference in the activation of these dimensions across the regimes.

4. Proposed Design Methodology

The methodology of this study is a hybrid visual analysis approach conjoining systematic visual content coding to structured comparative assessment of the ways in which the Indian women politician regime work to construct the representation of India women politicians. It was cross-regime in nature and the portrait image was the unit of analysis. The images were coded individually as per a pre-established system of visual coding, permitting within-regime and cross-regime comparisons. The focus of the methodology is more on interpretability and transparency, on the variables that are theoretically supported by existing literature on the visual politics and gender representation.

4.1. Visual Coding Framework

The visual coding framework was developed iteratively through a review of prior studies and pilot coding on a subset of images. The final framework captures five primary dimensions that recur across the three portrait regimes:

· Setting: institutional/official, campaign/rally, media studio, outdoor/public space

· Pose and Gaze: direct gaze, off-camera gaze; static pose, expressive gesture

· Affect: neutral/serious, smiling/approachable, assertive/emotive

· Symbolism: presence of party symbols, national symbols, slogans, or senior leader association

· Textual Elements: absence or presence of text overlays, slogans, captions, or headlines

Operationalization of all the variables was clearly defined with mutually exclusive categories in order to minimize the confusion in coding. It is through this framework that it is possible to establish patterns in terms of authority projection, personalization, dramatization and relational positioning.

4.2. Coding Procedure

The visual analysis was performed with the help of a team of trained coders and the complete codebook. To be consistent coders have been given a comprehensive guidance and an example image of each category. Image coding was performed in a semi-blinded fashion, whereby there was no knowledge of regime labels in the first round, so as to reduce confirmation bias. After the independent coding, regime labels were brought back to do a comparative analysis.

4.3. Inter-Coder Reliability

To determine the consistency of the coding procedure, a random chosen sample of the data was double-coded by several coders. Standard agreement metrics that were suitable when dealing with categorical data were used to measure inter-coder reliability. The findings showed that there was a great degree of consistency in the main variables, showing that coding framework was strong and repeatable. Differences were debated and agreed upon by consensus and limited refinements were undertaken on category definitions whenever required.

4.4. Analytical Strategy

Coded data were summed up so that the visual features can be compared on the basis of regimes. Distributional patterns were analyzed using descriptive statistics and comparative analyses were developed to establish systemic differences between official, party and media portraits. This research technique offers a strict basis to the findings and discussion in the following section.

5. Comparative Analysis of Portrait Regimes

Instead of viewing these regimes as ontologically detached visual spaces, the discussion places strong emphasis on how the respective regimes mobilize varying representational logics that determine how leadership, power, and gendered self is perceived. Institutional continuity and legitimacy According to an official portraiture, a logical visual sense of continuity and legitimacy prevails. Images within this regime often have formal contexts of the offices or other institutions, as well as controlled facial expression, direct gaze, and a stationary posture. Symbolic features are rudimentary and in the few instances that they exist, they are confined mostly to national or institutional insignia. All these visual selections have the effect of downplaying the personal and emotional, placing women politicians in the role of somewhat neutral agents of the state ahead of them as a personal political figure. The concern with formality, restraint is an attempt to anticipate control of government rather than political competition. On the contrary, party muralizations occupy a mobilization and ideology visual logic. These pictures are usually placed in the context of a campaign, a rally, or in some digitally made poster, and they often include the colors used by a party, their logos, their slogans, and the subjective connection to senior party leaders. Poses are more animation and expressive and the gazes are directed outward or the supporters or the supposition of the audience. It is common in party portraits to have a balance between assertiveness and approachability due to the general dual demands of women leaders such as being strong but relatable. Using these visual tactics, the portraits of the parties engrave the singular political figures into a shared political identity by focusing on devotion, affiliation, and ideological integrity. Newspaper imagery is informed by journalistic standards and the dynamics of attention through the prism of the platform, meaning it looks more dramatized and personalized. Close-ups, high contrast, and the emotive effect are common elements in images in this regime. The overlays of texts like headlines or captions are anticipated to place the image in a conflict, controversy, or urgent context. It is common to women politicians, where facial expression and demeanor heightens scrutiny and affective cues have become more visible because of this regime. Although these images make the members more noticeable, they also contribute to the threat of stereotyping gender because they focus on emotion over authority. In order to summarise these observations, Table 2 gives an overview of the prominent visual features of the three portrait regimes in a comparative summary. Differences in visual goals, settings, symbolic content, affect and extent of personalization regime-wise are synthesized in the table and provide a brief summary of the systematic variation of the representation across contexts.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Regime-wise Comparison of Visual Representation of Indian Women Politicians |

|||

|

Visual Dimension |

Official Portraits |

Party Portraits |

Media Portraits |

|

Primary visual objective |

Institutional legitimacy |

Ideological mobilization |

Newsworthiness and attention |

|

Dominant setting |

Government offices, institutional

backdrops |

Rallies, campaign stages, graphic

posters |

Studios, event sites, debate venues |

|

Affect and expression |

Neutral, controlled, formal |

Assertive yet approachable |

Highly expressive, emotive |

|

Pose and gaze |

Static posture, direct gaze |

Dynamic gestures, crowd-facing |

Close-ups, expressive moments |

|

Symbolic elements |

National or institutional symbols

(limited) |

Party logos, slogans, leader

association |

Minimal symbols; emphasis on context |

|

Textual overlays |

Rare or absent |

Frequent (slogans, campaign messaging) |

Frequent (headlines, captions) |

|

Degree of personalization |

Low |

Moderate |

High |

|

Gendered framing tendency |

Authority-focused, de-gendered |

Relational and collective positioning |

Emotionalization and scrutiny |

|

Overall visual logic |

Governance and continuity |

Collective identity and loyalty |

Individualization and dramatization |

Exhibited in Table 2, the three regimes of portraits mobilize varied visual logics that organize the discursive representation of the Indian women politicians by public. Official portraits feature power and organizational continuity, party portraits feature affiliation with group and ideological sympathy and the features of media portraits forecast personal character and feeling of saliency. It is a comparative synthesis that forms the analytical basis of the interpretive insights that were produced in the ensuing section.

6. Case Study–Based Evaluation

To augment the regime level comparative analysis, this section is a case study based assessment that demonstrates how the operation of the regimes is applied to individual Indian women politicians. The case studies offer greater analysis than they would do in the context of statistical generalization, showing the implementation of the visual logics determined above in official, party, and media arenas by the same political actors.

1) Case

Selection Rationale

Cases were selected using a maximum-variation strategy, focusing on women politicians who (i) hold visible public roles, (ii) maintain sustained presence across official, party, and media platforms, and (iii) operate within differing political and media environments. This approach enables examination of regime-specific visual strategies while accounting for variation in political role and public exposure.

2) Cross-Regime

Portrait Comparison

The political portraits always kept the politician in institutionalized scenes, in a neutral disposition, restrained pose and the minimum symbolism. These pictures prefigured administration and authority and carefully restrained personality. Party portraits, in their turn, were more focused on ideological alignment and mobilization. Party logos, slogans and campaign settings were also more prominently displayed as well as poses being more dynamic, with many stating assertiveness or outreach. The strength paired with approachability of affect in party portraits placed the politician in a shared political identity and not as an independent actor. The most dramatization and personality was shown in the media portraits. Close-up shots, emotional appeal, and contextualizing the discussions, press events, or even mass gatherings were used extensively, often with overlaying texts like headlines or captions. These descriptions increased the exposure of individuals and at the same time, amplified criticism of expression and attitude. In order to specify these regime-wise changes at the individual level, Table 3 displays a case-wise comparison of visual features among portrait regimes.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Case Study–Wise Comparison of Portrait Regimes (Sample Data) |

||||||

|

Case ID |

Portrait Regime |

Setting |

Affect |

Symbolism Presence |

Text Overlay |

Degree of Personalization |

|

Case A |

Official |

Institutional office |

Neutral |

National emblem |

No |

Low |

|

Case A |

Party |

Campaign stage |

Assertive |

Party logo + slogan |

Yes |

Medium |

|

Case A |

Media |

Debate studio |

Emotive |

None |

Yes (headline) |

High |

|

Case B |

Official |

Government backdrop |

Neutral |

Institutional seal |

No |

Low |

|

Case B |

Party |

Digital campaign poster |

Approachable |

Party logo |

Yes |

Medium |

|

Case B |

Media |

Public event |

Emotive |

Contextual cues |

Yes |

High |

|

Case C |

Official |

Ministry office |

Neutral |

National symbol |

No |

Low |

|

Case C |

Party |

Rally setting |

Assertive |

Party logo + leader image |

Yes |

Medium |

|

Case C |

Media |

Press interaction |

Expressive |

None |

Yes |

High |

As indicated in Table 3, the identical political actor is visually recreated across regimes, where there exists a systematic variation of setting, affect, symbolic density, and personalization. Whereas official portraits equilibrate power by restrain, party portraits inscribe the actor in ideological discourses, whereas media portraits are more individual and emotionally salient.

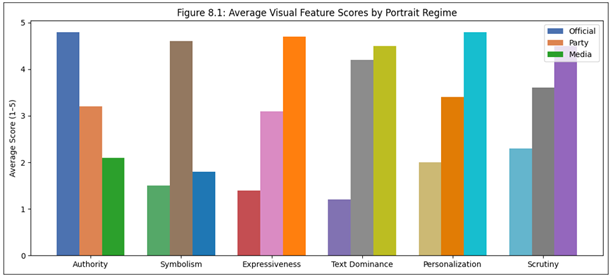

6.1. Quantified Visual Pattern Assessment

In order to consolidate further these qualitative observations, the selected visual dimensions were grouped into quantified coding scores. These scores give a numerically interpretable overview of regime-based tendencies across the case studies to allow visual dominant tendencies to be better compared. Table 4 shows the average scores of important visual dimensions in portrait regimes on a standardized scale (five-point scale).

Table 4

|

Table 4 Average Visual Feature Scores by Portrait Regime (Sample Data) |

|||

|

Visual Dimension |

Official Portraits |

Party Portraits |

Media Portraits |

|

Institutional authority |

4.8 |

3.2 |

2.1 |

|

Ideological symbolism |

1.5 |

4.6 |

1.8 |

|

Emotional expressiveness |

1.4 |

3.1 |

4.7 |

|

Textual dominance |

1.2 |

4.2 |

4.5 |

|

Personalization |

2.0 |

3.4 |

4.8 |

|

Gendered scrutiny |

2.3 |

3.6 |

4.5 |

|

(Scale: 1 = Low, 5 = High) |

|||

The qualitative results obtained in Table 4 are supported by the quantified data. Institutional authority is highest followed by low scores on expressiveness and personalization of emotion in official portraits. The portraits of the parties take an intermediate place with a high level of ideological symbolism, and moderate personalization. On the other hand, the media portraits have the most emotional expressiveness, textual power, and closeness, as the importance of dramatizing and personalizing political leadership remains essential.

7. Analysis and Discussion

This part is a synthesis of the results obtained in the comparative regime analysis and the case study-based analysis to explain how visual regimes of portrait influence the overall representation of their image by the masses to Indian women politicians. The discussion provides both structural and contextual differences in visual political communication because it combines both the regime-level trends and the individual-level evidence. Systematic differences were found across the dataset in terms of the official, party and media portrait regimes. Formal portraits always accentuated institutional power with unemotional emotion, the use of official environments and the abbreviation of personalization. These pictures displayed legitimacy and continuity but tended to down-play the leadership qualities of individuals. The portraits of parties held a middle place, suggesting both aggressive attitudes and ideological symbolism and sharing elements of approachability. Party portraits incorporated women politicians into more general political discourses using party logos, slogans, and collective images but retained individual identity to some extent.

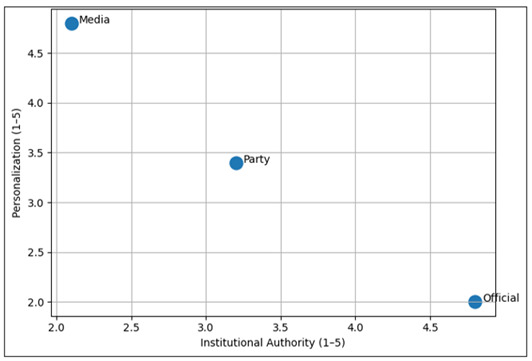

Figure 3

Figure 3 Average Visual Feature Scores by Portrait Regime

Media portraits on the other hand had the most dramatization and personalization display with far too often close-up framings, expressive affect prefiguration, and contextual indicators of conflict or immediacy as seen in Figure 3. These pattern of regimes, at the individual level, were supported by the case study-based evaluation. These visual reconstructions of the same political actors were made between different regimes at the same time proving that there were no individual specifics of representation only but rather regime-determined production logics.

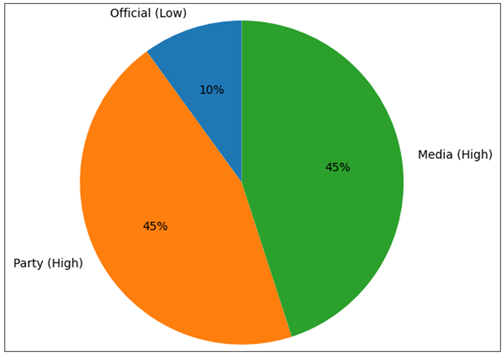

Figure 4

Figure 4 Text Overlay Prevalence Across Portrait Regimes

The results of the study indicate that gendered visual framing works differently in the regimes of portraits. Official portraits were inclined to de-genderization of the image, the repression of emotionality, visual indicators of the personality as shown in Figure 4 and fitted women leaders with the model of masculine leadership historically instilled in the conventions of institutions. Even though party portraits were more visible and expressive, they often placed women politicians in a relational way such as by association with party leadership or by collective representation, which strengthened gendered expectations of loyalty and representation.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Authority–Personalization Trade-off by Portrait Regime

Gendered scrutiny was most intensified via media portraits, where issues of affect, demeanor and moments of expression received more attention, which boosts the chances of an emotionalized interpretation. One of the most important lessons gained in the course of the analysis is the trade-off between authority and personalization of the regimes. Though the official portraits made the most of authority at the expense of individuality, media portraits increased publicity and relatability and probably weakened the perceptions of institutional competence as shown in Figure 5. The portraits of parties tried to strike the right balance between these conflicting needs but still were limited by the ideological framing and shared symbolism. These trade-offs indicate a limited visual area through which women politicians operate in which leadership legitimacy is undertaken through a series of representational situations. The findings highlight the need to interpret political portraits as visual political construction as opposed to their objective depiction. The role of portrait regimes in women politicians is that in addition to their visibility, the frames in which leadership, competence, and credibility are evaluated are also constructed. Findings add to the field of visual politics by exhibiting the necessity of cross-regime analysis, integrated and cross-regime analysis; it illustrates the importance of the visual encoding and reproduction of gendered expectations in democratic representation.

8. Conclusion and Future Research Directions

This work examines the role of official, party, and media portrait regimes in defining the visual image of Indian women politicians to go beyond the analysis of individual images and adopt the comparative and regime-based concept of political imagery. The combination of visual content coding, comparative analysis, and case study-based appraisal proves that political portraits are no longer such images as they are not neutral images but their formation is under the influence of certain institutional, ideological, and media logic. Portraits of authorities emphasize authority, impartiality, and continuity of the state, and frequently, individual and gendered indicators are suppressed. The portraits of party women politicians fit into shared ideological histories, being both assertive and approachable and making use of symbolic and mobilizing imagery. Portraits in the media, on the other hand, pre-empt individualization and expressiveness, which increases visibility, but at the same time increases gendered examination. The evidence shows that a visual trade-off between authority and personalization is constant, and women politicians’ resort to limited representational spaces by regimes. Although official imagery is legitimate, restrictive to individuality; media imagery is more recognizable but prone to emotionalization; party imagery would be the mediator between the two extremes but is still subjected to ideological framing. These dynamics point out the reproduction of gendered expectations in the visual systems of democratic communication.

To build on this study, future studies can take it in a number of directions. Primarily, longitudinal study may be used to investigate that portrait regimes change over the course of electoral periods or leadership paths. Second, cross-country or political regime analyses would assist in determining the universal nature of regime-based visual logic. Third, the combination of computational vision methods with qualitative coding has potential to perform the analysis of political imagery at large scale. Lastly, the role of the various regimes of portraits in voter perception, trust, and assessment of leadership can be examined during audience reception studies. A combination of these orientations can contribute further to the development of knowledge about visual politics and feminized representation in the present democracies.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Ajani, S. N., Saoji, S., Maindargi, S. C., Rao, P. H., Patil, R. V., and Khurana, D. S. (2025). Mapping Pathways for Inclusive Digital Payment Ecosystems: Integrating NGOs, Micro-Insurance Startups, And Community Groups. Enterprise Development and Microfinance, 35(1), 61–81. https://doi.org/10.3362/1755-1986.25-00004

Bhowmick, D. (2024). Political Ecology of Climate Change in Sundarbans, India: Understanding Well-Being, Social Vulnerabilities, and Community Perception. Environmental Quality Management, 33(3), 371–382. https://doi.org/10.1002/tqem.22125

Courtney, M., Breen, M., McGing, C., McMenamin, I., O’Malley, E., and Rafter, K. (2020). Underrepresenting Reality? Media Coverage of Women in Politics and Sport. Social Science Quarterly, 101(4), 1282–1302. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12826

Galy-Badenas, F., and Gray, F. E. (2020). Media Coverage of Rachida Dati and Najat Vallaud-Belkacem: An Intersectional Analysis of Representations of Minority Women in the French Political Context. Women’s Studies in Communication, 43(2), 181–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/07491409.2020.1740900

Gogoi, P., and Bordoloi, M. B. (2024). A Review of the Protection of Women’s Rights: An Indian Perspective. International Journal of Research in Social Science and Humanities, 5(5), 94–99. https://doi.org/10.47505/IJRSS.2024.5.8

Klanjšek, R. (n.d.). Gender Equality And Empowerment of Women in Politics: An Overview. In S. Košir (Ed.), Empowering Women’s Political Participation (37–59). ToKnowPress. https://doi.org/10.53615/978-83-65020-52-9/37-59

Liu, J., Li, X., Liu, Y., and Wang, L. (2020). The Impact of Social Media on Young Consumers’ Environmentally Friendly Consumption Behavior: Evidence From China. Sustainability, 12, 3189. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083189

Magdum, P., and Bhattacharya, B. (2021). Women in

Indian Cinema. Publication Division.

Ministry of Panchayat

Raj, Government of India. (2019). Basic Statistics of Panchayati

Raj Institutions. Government of India.

Mishra, D. (2015). Portrayal of Women in Media. Journal of Higher Education and Research Society, 3(2), 122–128.

Ono, Y., and Endo, Y. (2024). The Underrepresentation of Women in Politics: A Literature Review on Gender Bias in Political Recruitment Processes. Interdisciplinary Information Sciences, 30(1), 36–53. https://doi.org/10.4036/iis.2024.R.01

Reshma, K. S., and Manjula, K. T. (2024). A Systematic Review of Literature Critiquing the Representation of Muslim Women in the Works of Selected Indian Muslim Women Novelists. International Journal of Management, Technology and Social Sciences, 9(1), 47–70. https://doi.org/10.47992/IJMTS.2581.6012.0332

Saranya, R., Ramanathan, A., Bharkavi, I. S. K., and Balasubramaniam, M. (2024). The Incredible Story of India’s Revolutionary Feminist: Dr. Muthulakshmi Reddy (1886–1968). Cureus, 16(6), e62644. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.62644

Saville, N. M., Uppal, R., Odunga, S. A., Kedia, S., Odero, H. O., Tanaka, S., Kiwuwa-Muyingo, S., Eleh, L., Venkatesh, S., Zeinali, Z., Koay, A., Buse, K., Verma, R., and Hawkes, S. (2024). Pathways to Leadership: What Accounts for Women’s (In)Equitable Career Paths in the Health Sectors in India and Kenya? A Scoping Review. BMJ Global Health, 9(7), e014745. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2023-014745

Snipes, A., and Mudde, C. (2020). France’s (Kinder, Gentler) Extremist: Marine Le Pen, Intersectionality, and Media Framing of Female Populist Radical Right Leaders. Politics and Gender, 16(2), 438–470. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X19000370

Sultania, A. (2024). Are We Underestimating the Success of Self-Help Groups in India? A Systematic Review. Open Journal of Business and Management, 12(4), 2640–2661. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojbm.2024.124137

Van der Pas, D. J., and Aaldering, L. (2020). Gender Differences in Political Media Coverage: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Communication, 70(1), 114–143. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqz046

Williams, B. E. (2020). A Tale of Two Women: A Comparative Gendered Media Analysis of UK Prime Ministers Margaret Thatcher and Theresa May. Parliamentary Affairs, 74(2), 398–420. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsaa008

Zaiats, N., Rega, I., Boiko, V., Shlieina, L., and Toporkova, M. (2024). Ensuring Gender Equality and Legal Protection of Women’s Rights: Achievements, Challenges, and Prospects. Multidisciplinary Science Journal, 6.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2026. All Rights Reserved.