ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Visual Design Thinking for Digital banking: Comparative Insights from Co-operative Institutions

Jyotirmayee Vishvajit Bhosale 1![]() , Dr. Deepali Satish Pisal 2

, Dr. Deepali Satish Pisal 2![]()

![]()

1 Research

Scholar, Department of Management, Bharati Vidyapeeth (Deemed to be

University), Institute of Management and Entrepreneurship Development Pune,

State Maharashtra, India

2 Assistant

Professor, Department of Management, Bharati Vidyapeeth (Deemed to be

University), Institute of Management and Entrepreneurship Development Pune,

State Maharashtra, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The high level

of digitalization of financial services has altered customer-customer

interaction with the banking platform, which has put visual design thinking

at the center of innovation in digital banking. As commercial banks have

actively pursued the user-centric digital interfaces, co-operative banking

institutions that are based on shared values of communities and

relationship-based services have distinct challenges and opportunities in how

their ethos can become successful in digital experiences. This paper examines

visual design thinking in digital banking and gives some comparative analysis

on co-operative institutions and the mainstream commercial banks. The study

analyzes the effect of the visual aspects of design like the simplicity of

the interface, hierarchy of information, accessibility, the psychology of

color and customer engagement to usability, trust, and customer engagement

across digital banking systems. The research applies a comparative framework

in the analysis of mobile and web interfaces of the chosen co-operative and

commercial banks and is backed by the principles of user experience (UI) and

design thinking phases such as empathize, define, ideate, prototype, and

test. The specific focus is on the way co-operative banks are changing the

visual design to suit different, often semi-urban and rural audiences with

different degrees of digital literacy. The results have shown that commercial

banks focus on efficiency and personalization and rich-features dashboards

whereas co-operative institutions focus on clarity, familiarity and

trust-building visuals. Nevertheless, inconsistencies, responsiveness, and

compliance to accessibility still exist in most co-operative online

platforms. The research paper has identified the best practices and design

solutions that can help co-operative banks strike a balance between

technological modernization and their social and community-based identity. |

|||

|

Received 26 June 2025 Accepted 09 October 2025 Published 28 December 2025 Corresponding Author Jyotirmayee

Vishvajit Bhosale, jyotirmayee.bhosale@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i5s.2025.6980 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Visual Design Thinking, Digital Banking, Co-Operative

Banks, User Experience (UX), Inclusive Interface Design, Trust and

Accessibility |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The fast change of digital banking has fundamentally transformed the nature of the delivery, access, and experience of financial services, making the user experience (UX) and the visual design thinking the strategic differentiators, instead of the fringe of aesthetic concerns Alawaji and Aloraini (2025). Digital banking platforms are no longer considered based on their functional efficiency only, but rather they are evaluated based on their clarity, usability, accessibility, and emotional appeal incorporated into the visual interfaces Scarlat (2022). The visual design thinking based on principles of human-centered design incorporates the empathy, ideation, and iterative prototyping to match the digital interfaces to the needs of users, their cognitive ability, and expectations Chen (2024). Visual design is especially important in the banking sector where the perception of customers, the level of security, and ease of use rank as supreme factors, and the digital touchpoints must be more engaging.

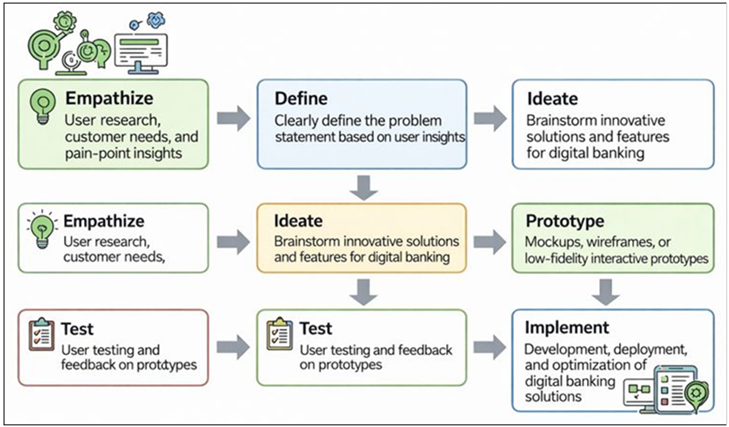

Although major commercial banks are fast moving towards design of sophisticated interfaces, personalization algorithms, and consistent omnichannel interactions, the co-operative banking institutions introduce a rather different but under-researched landscape Polasik et al. (2024). Co-operative banks are historically community based, member based and socially implanted institutions that tend to target heterogeneous users groups such as semi-urban, rural, elderly, and digitally novice communities. To translate these values into the digital realms it is essential to use the visual design thinking subtly by focusing on simplicity, familiarity, and inclusiveness without harming functional strength Abraham et al. (2023). But most of the co-operative institutions exhibit structural limitations like lack of technological resources, old systems, and conservative cultures of innovation, which frequently lead to divided visual identities and non-optimized online experiences. The Figure 1 shows a systematic design thinking process of digital banking, starting with user empathy and further to implementation. It presents the role of user insights, problem definition, ideation, prototyping, testing and deployment in providing intuitive, efficient and trustful digital banking solutions.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Visual Design Thinking Workflow for User-Centric

Digital Banking

This contrasting gap between commercial and co-operative digital banking platforms highlights the relevance of conceptualizing and applying the visual design thinking to the institutional contexts systematically Suryawanshi et al. (2024). Color schemes, typography, iconography, navigation structure, feedback, and accessibility are some of the elements that affect usability, as well as perceived factors of credibility and emotional comfort, which are particularly important in trust-based financial relationships. In addition, the visual language and interaction flow inconsistencies may have a disproportionate impact on the user with low digital literacy, thus expanding the digital inclusion gap Pluskota et al. (2025).

It is on this background that the current research places the visual design thinking as a strategic platform by which the digital banking interfaces can be redesigned in co-operative institutions. The study will provide comparison issues with commercial banking systems to bring to the fore design practices that have managed to ensure that technological modernization is not at the expense of community values. The application of the principles of design thinking to co-operative digital banking is not an issue of the design refinement, but a journey to increasing the user confidence, transparency of operations, and wholesome financial inclusion. In this perspective, the visual design can be seen as a significant facilitator of the long-term digital transformation in co-operative banking ecosystems.

2. Conceptual Foundations

2.1. Principles of Design Thinking

Design thinking is a design-oriented problem-solving method, which involves human-centered, iterative problem-solving where the focus of a problem is on the user needs, re-framing the problem, and providing innovative solutions through continuous feedback. More fundamentally, design thinking has been designed with five stages that interact with each other empathize, define, ideate, prototype, and test. These principles allow the designers and decision-makers to focus more on the real financial behaviors, emotions, and limitations of the users, rather than on technology-oriented solutions, in the context of digital banking, especially co-operative institutions Negrea et al. (2025). The empathize phase is concerned with a thorough comprehension of the various segments of users, such as older customers, the rural community, and those not digitally savvy which are usually the main clients of the co-operative banks. Ideation promotes imaginative consideration of visual and interaction resolutions that streamline difficult banking tasks devoid of undermining security Al-Qudah et al. (2024). Designing and testing then enable institutions to successively correct interfaces as users give feedback instead of basing on assumptions. Design thinking encourages experimentation and learning unlike linear development models, which is especially useful to co-operative banks working within the constraints of resource and legacy-systems.

2.2. Visual Design Elements in Digital Interfaces

The visual elements of design constitute the surface layer with the help of which the users see, interpret, and engage with digital banking interfaces. These aspects encompass color schemes, typography, iconography, structure of the layout, space, imagery and visual feedback. In online banking, visual design is not just a question of aesthetics but it has a direct impact on usability, understanding, and emotional appeal. The hierarchical arrangement of information, by maintaining regular typefaces and spacing, allows users to quickly find important features like balance inquiries, transfers and transaction histories Alkhwaldi et al. (2022). The use of responsive layouts and visual consistency between the devices also improve the usability because they maintain smooth experiences when using smartphones, tablets, and desktops. In the case of co-operative banking institutions, there should also be a balancing of visual design between the modern digital and familiarity and cultural sensitivity, not overly complex and abstract design which will make them unfamiliar to the traditional users. Interfaces that are poorly designed have a lot of garbage, uneven graphics, or low contrast which raises the error rate and decreases trust in digital transactions.

2.3. User Experience (UX) and Trust in Digital Banking

User experience (UX) in digital banking refers to the general impression that users have when using banking solutions, based on how easy the solutions are to use, how efficient they are, how comforting they are to the user emotionally, and how reliable they appear. The basic element of UX in the financial services sector is trust because users must provide valuable personal and financial data, whilst they must use digital systems to conduct important transactions. An effective UX is less uncertain, offering easy routes to follow, accurate system behavior and communication of transaction result. The visual messages like confirmation, progress, and error messages inform the users that they have successfully performed some action or one that should help them correct the error. When there is consistency in the interface design this also contributes to trust by providing familiarity and minimizing the learning requirements among various banking operations. Co-operative digital banking involves trust as personal relationship and credibility within their community, so UX design plays a key role in mediating between the traditional banking values and the digital interaction Persia and D’Auria (2017). Hurdles in the work process due to complicated flowcharts, unclear naming, or slow reaction of the system may lead to a lack of trust, especially in the case of a novice or an older user.

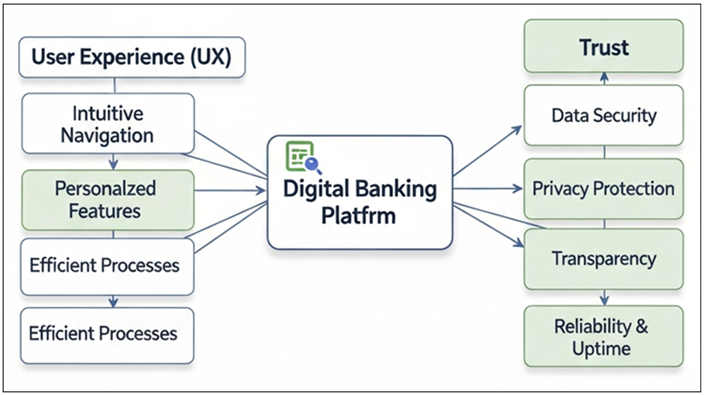

Figure 2

Figure 2

Conceptual Block

Diagram of User Experience (UX) and Trust Formation in Digital Banking

The image 2 shows how a positive digital banking experience is created by combining core UX elements with trust factors. The combination of intuitive design, performance, and usability with security, transparency, and support leads to greater customer satisfaction, which eventually results in the long-term trust and loyalty in digital banking platforms.

3. Overview of Digital Banking Ecosystems

3.1. Evolution of Digital Banking Platforms

Digital banking technologies have gone through several technological and conceptual stages, starting as simple automation features and moving on to advanced and user-friendly ecosystems. The first phase of digital banking involved back-end computerization and the banks were applying information systems in the internal record keeping, accounting and processing of the transactions. This stage provided little customer contact and used physical branches to a significant degree. As the internet emerged in the late 1990s/early 2000s, banks launched online banking portals that allowed clients to check their balances, view my statements and do simple transfers. These platforms were mostly functional, putting either security or accuracy in transactions on the forefront of focus rather than usability or design Gaviyau and Godi (2025). The following step was the development of mobile banking which resulted in the adoption of smartphones and turned the whole user expectations upside down as everything was possible everywhere. This change spurred the demand of responsive interfaces, ease of navigation, and appearance. More recently, digital banking is entering a platform-oriented age where it is personalized, data-informed, API-enabled, and omnichannel experiences.

3.2. Characteristics of Commercial Banking Digital Systems

The digital systems that define commercial banking are often highly technical systems with high scale and richness of features. These organizations usually exist within very competitive markets and this forces them to invest on state-of-the-art digital infrastructure and innovation. The efficiency, speed, and personalization of their digital platforms provide services like real-time payments, smart dashboards and AI-driven recommendations, and a smooth integration of mobile, web and third-party financial applications. Commercial banking systems tend to be aligned to visual design that is based on robust brand identities, the use of refined aesthetics and color scheme, and contemporary interaction patterns. The user interfaces are also designed to accommodate frequent digital users and the layering of the functionalities and customizable views suits different segments of customers Indrasari et al. (2022). Security and compliance are integrated to a high degree, and in most cases, the communication of these components is done visually, by displaying indicators of encryption, biometric authentication, and transaction confirmation. Commercial banks also use broad user information to optimize the UX by personalizing in response to analytics, a dynamic layout, and advisory interventions. This sophistication can however lead to complex interfaces which presuppose higher digital literacy. Although commercial banking platforms are best in the areas of innovation, speed, and globalization, they can be less concerned with simplicity and inclusivity towards digitally vulnerable populations. In general, commercial digital banking systems are technologically developed ecosystems in which the visual design thinking is directly connected with the competitiveness differentiation, customer retention, and operational efficiency Michailidis (2024).

3.3. Characteristics of Co-operative Banking Digital Systems

Co-operative banking digital systems are based on the unique institutional values and operational realities of co-operative financial institutions, which place greater emphasis on the welfare of the member, community participation and relationship-oriented banking. Unlike commercial banks, co-operative banks frequently deliver services to localised or region-based communities, such as rural, semi-urban, elderly and digitally novice clients. Consequently, they are more likely to develop their digital platforms with core banking operations and not rich features. The key features are simplicity, familiarity, and trust-building which is frequently manifested in simplistic navigation, a lack of deep menu, and restrained visual design decisions. Nevertheless, other co-operative digital systems may encounter some obstacles including the legacy core banking infrastructure, low budgets, and slow cycles of technology uptake. Personalization and advanced analytics are also less common in comparison with commercial systems and updates can be gradual instead of radical Amiri et al. (2023). Meanwhile, co-operative banks have a special edge of matching digital experiences with high-quality offline trust and community credibility. Their digital platforms can support these values when well designed by the effective communication, well-understood and transparent workflow, and visually aware of cultural signals. Therefore, co-operative digital banking systems are a developing ecosystem in which visual design thinking integration has a high potential to promote usability, inclusivity and digital confidence and maintain the social and community oriented mission of the institution [16].

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary Comparison of Digital Banking Ecosystems |

||||

|

Parameter |

Traditional Digital Banking |

Commercial Banking Digital

Systems |

Co-operative Banking Digital

Systems |

Design Thinking Implication |

|

Primary Objective |

Transaction automation |

Efficiency, scale,

competitiveness |

Member service and community

support |

Shift from system-centric to

human-centric design |

|

User Base |

Branch-dependent customers |

Digitally mature, urban,

diverse users |

Semi-urban, rural, elderly,

digitally novice users |

Strong need for

empathy-driven design |

|

Feature Complexity |

Basic functions (balance,

statements) |

Feature-rich, personalized

services |

Essential and limited

feature set |

Balance simplicity with

functionality |

|

Visual Design Style |

Minimal, utilitarian |

Modern, polished,

brand-driven |

Conservative, familiar,

trust-oriented |

Context-sensitive visual

design required |

|

Interface Navigation |

Linear and rigid |

Dynamic, multi-layered |

Simple, shallow navigation |

Reduce cognitive load for

inclusion |

|

Technology Infrastructure |

Legacy systems |

Cloud-based, API-driven,

AI-enabled |

Mixed legacy and modern

systems |

Incremental, adaptive design

strategies |

|

Personalization Level |

None or very limited |

High (AI-driven dashboards,

alerts) |

Low to moderate |

Opportunity for ethical,

simple personalization |

|

Accessibility &

Inclusivity |

Largely overlooked |

Improving but secondary |

Critical but inconsistently

implemented |

Inclusive design as a core

principle |

This Table 1 briefly outlines the evolving digital banking ecosystem features in comparison to each other and how visual design thinking is becoming a strategic part especially in enhancing co-operative digital banking platforms.

4. Visual Design Thinking Framework for Digital Banking

The framework of thinking visual design offers a hierarchy and loose method of creating user friendly digital banking interfaces, especially appropriate in the realm of diverse and trust sensitive co-operative institutions. The framework is implemented in four connecting steps empathize, defining, ideating, and prototyping each providing an input to the development of affordable, accessible, and aesthetically consistent digital banking experiences.

4.1. Empathize: Understanding Diverse Banking Users

The empathize step is the one that is aimed at developing a profound understanding of the behavioural patterns, expectations, and constraints of various banking users. This covers the aged population, rural and semi-urban populations, and users with low digital literacy in co-operative digital banking. The empathy based research techniques like user interview, contextual inquiry and observation assists the designers in comprehending the points of pain as it pertains to navigation confusion, security anxiety, language barriers, and visual overload. This step makes sure that the decisions made on the visual design are based on actual user scenarios as opposed to presumed technical expertise.

Define: usability and accessibility issues

The define stage, which is based on empathic insights, defines clear usability and accessibility issues. The problems that can often be encountered are complicated workflows, uneven visual hierarchy, low contrast text, undefined icons, and unintuitive navigation sequence. In the case of co-operative banks, these issues can also be specified by the identification of infrastructural limits and regulatory demands. Problem statements are a clear way of guiding the design priorities towards the minimization of cognitive loads, enhanced readability, and accessibility by users with different physical and cognitive capacities.

Propagate: Visual Solutions of Banking Interfaces

During the ideation stage, creative visual solutions are explored to solve formulated challenges. These are simplified layouts, color palettes understandable by a specific culture, familiar iconography, gradual delivery of information and distinct visual feedback during transactions. Design concepts undergo consideration on the capacity to develop trust, clarity and usability and preserve institutional identity.

Prototype and Test: Design Testing

Prototyping and testing create ideas into visualized interface models that could be tested against actual users. Prototyping (low- and high-fidelity) allows a quick feedback, usability test and refinement process. It is a cyclical validation of visual design solutions that can be kept in accordance with user needs, which will build confidence, adoption, and continued participation in digital banking platforms.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Comparative Analysis of Visual Design Thinking in Digital Banking |

|||||

|

Parameter |

Commercial Banking Digital

Systems |

Co-operative Banking Digital

Systems |

Visual Design Thinking Focus |

Key Gap Identified |

Improvement Opportunity |

|

User Diversity |

Digitally skilled, urban,

multi-segment users |

Rural, semi-urban, elderly,

digitally novice users |

Empathy-driven user

understanding |

Limited user research depth |

Context-aware user studies |

|

Design Orientation |

Innovation and

feature-driven |

Simplicity and

familiarity-driven |

Human-centered design

alignment |

Overly conservative visuals |

Modern yet familiar

interfaces |

|

Interface Complexity |

Multi-layered, feature-rich |

Shallow, function-focused |

Cognitive load reduction |

Underutilized visual

hierarchy |

Progressive disclosure |

|

Visual Consistency |

Strong branding and

consistency |

Often fragmented across

platforms |

Unified visual language |

Inconsistent UI standards |

Standardized design systems |

|

Prototyping Practice |

Continuous A/B testing |

Limited or ad-hoc testing |

Iterative validation |

Minimal usability testing |

Low-cost rapid prototyping |

|

Innovation Speed |

Fast, continuous iteration |

Slow, incremental updates |

Agile design cycles |

Legacy constraints |

Phased design upgrades |

|

UX Maturity |

High and evolving |

Moderate and emerging |

Design thinking integration |

Partial framework adoption |

End-to-end design thinking |

The comparison of visual design thinking in Table 2 shows that it is entrenched in commercial banking systems with selective application in co-operative institutions.

5. Comparative Analysis Methodology

5.1. Selection of Co-operative and Commercial Banking Platforms

The choice of co-operative and commercial banking platforms is a decisive move towards making a balanced and meaningful comparative analysis of the visual design thinking in digital banking. The approach uses a purposive and representative sampling technique to help address the differences in the size of the institution, user populations, and digital maturity. The choice of the commercial banking platform is determined by its popularity, technological advancement and extensive digital platform on both mobile and web applications. These are usually banks with large mobile applications nationally or regionally, high volume of transactions and constant updating of the interface. Their platforms become the standard of the highly developed visual design, UX innovation, and personalization practices.

On the contrary, co-operative banking platforms are chosen to indicate diversity in geographic coverage, size of membership and the context of operation. Preference is also provided to urban and semi-urban co-operative banks that have either adopted mobile or internet banking solutions, and to a small number of rural co-operative institutions that are digitally underserved groups. The criteria used in the selection are availability of platforms, completeness of the functionality (balance inquiry, transfers, bill payments) and active use. This guarantees that platforms which provide similar core services are compared even in case of variations in the depth of features. Also, regulatory compliance and language support are taken into account, as they have a considerable effect on the interface design and his or her usability in the co-operative situations.

5.2. Evaluation Criteria for Visual Design and UX

The criteria of visual design and user experience (UX) evaluation are based on the heuristics of the UX and the design thinking principles, as well as on the accessibility standards. Parameters used to evaluate visual design include the layout clarity, the hierarchy of information, the readability of the typography, the use of colors, coherence of icons and the presence of visual feedback. These aspects are analyzed to find out the effectiveness of interfaces in terms of directing user attention, lightening the cognitive load, and conveying trust and security. Coherence between screens and other devices is also tested since discontinuous visual language has an adverse impact on functionality and perceived trustworthiness.

Aesthetics is only one aspect of UX evaluation because there is also navigational efficiency, flow of tasks, prevention of errors, and responsiveness of the system. The number of steps that one has to have to complete essential banking tasks, the readability of labels and instructions, and the system status are evaluated in a systematic manner. The aspects of accessibility like contrast ratios, font scaling, language choice, and elderly/visually impaired user support are the central component of the assessment, especially when it comes to co-operative banking websites. Issues like emotional and trusting elements, such as perceived security, reassurance by confirmations, and validity of transaction feedback, are also included. The combination of these criteria gives a holistic framework based on which one can compare the way visual design thinking is implemented into the functional, inclusive, and trustful digital banking experiences.

6. Comparative Insights and Findings

6.1. Interface Simplicity and Information Hierarchy

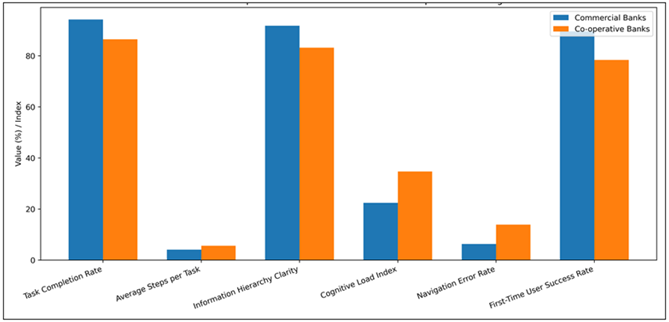

The interface simplicity and information hierarchy comparative analysis shows that commercial banking platforms have unquestionable advantages in terms of usability as they are represented in Table 3. The rate of task completion and the percentage of navigation errors are lower, which means that commercial interfaces are more intuitively designed and allow users to find and carry out the most important banking functions with minimal effort. The fact that strong visual hierarchy, consistent iconography and gradual disclosure of information make the difference between the lower average of steps per task and reduced index of cognitive load also proves to be successful. On the opposite, the layouts of co-operative banking platforms are denser, and elements are less distinctly prioritized, which makes it more cognitively difficult, especially to first-time users. The low initial user success rate is associated with the issues of learnability and onboarding implying that visual cues and guidance are not high enough.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Comparative Numerical Analysis |

|||

|

Parameter |

Commercial Banks (%) |

Co-operative Banks (%) |

Interpretation |

|

Task Completion Rate |

94.2 |

86.5 |

Commercial platforms enable

faster task success |

|

Average Steps per Task |

4.1 |

5.6 |

Co-operative interfaces

require more navigation |

|

Information Hierarchy

Clarity Score |

91.8 |

83.2 |

Stronger visual

prioritization in commercial apps |

|

Cognitive Load Index |

22.4 |

34.7 |

Higher mental effort in

co-operative systems |

|

Navigation Error Rate |

6.3 |

13.9 |

More user confusion in

co-operative interfaces |

|

First-Time User Success Rate |

89.6 |

78.4 |

Learning curve higher for

co-operative users |

Nonetheless, the performance variance does not mean that there is no functionality; it means that there is a desire to have a better visual organization. Co-operative banks can easily make usability much better without adding more features by making more sense of information grouping, increasing typography contrast, and simplifying the ways to get around. The Figure 3 shows the use of UX efficiency is more efficient in commercial banks and shows higher completion of tasks, better hierarchy of information, reduced cognitive load, and reduced number of errors in navigation that leads to a higher success rate of a first-time user than co-operative banking platforms.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Representation of performance comparison between

commercial and co-operative platform

On the whole, the results support the idea that simplicity of interface and clearly defined information hierarchy are the core of the user friction reduction and its further involvement in digital banking setting. The findings demonstrate that business banking sites perform better than co-operative systems with regards to simplicity of interface and hierarchy of information. There is clear visual prioritization, reduced number of steps and reduced cognitive load that helps in an increase in task efficiency. Co-operative platforms, though functionally sufficient, have higher layouts and poorer hierarchy, which impact the first-time and digitally inexperienced users.

6.3. Visual Identity, Branding, and Trust Perception

The simplicity of interface and information hierarchy comparison demonstrates the obvious usability benefits of commercial banking platforms. The rate of task completion and the percentage of navigation errors are lower, which means that commercial interfaces are more intuitively designed and allow users to find and carry out the most important banking functions with minimal effort. The fact that strong visual hierarchy, consistent iconography and gradual disclosure of information make the difference between the lower average of steps per task and reduced index of cognitive load also proves to be successful. On the opposite, the layouts of co-operative banking platforms are denser, and elements are less distinctly prioritized, which makes it more cognitively difficult, especially to first-time users.

Table 4

|

Table 4 Percentage-Based Findings |

||

|

Metric |

Commercial Banks (%) |

Co-operative Banks (%) |

|

Perceived Brand Consistency |

93.1 |

81.6 |

|

Visual Trust Indicators

Clarity |

91.4 |

84.2 |

|

Perceived Security

Confidence |

94.8 |

88.1 |

|

Interface Professionalism

Rating |

92.7 |

80.9 |

|

Emotional Comfort Score |

89.5 |

87.3 |

|

Overall Trust Perception |

93.6 |

89.2 |

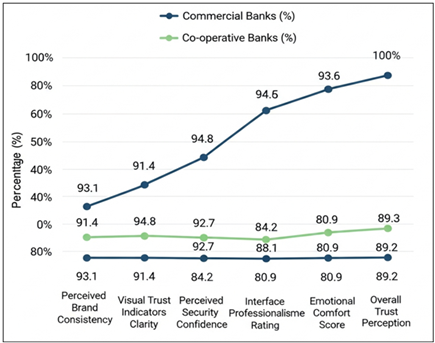

The low initial user success rate is associated with the issues of learnability and onboarding implying that visual cues and guidance are not high enough. Nonetheless, the performance variance does not mean that there is no functionality; it means that there is a desire to have a better visual organization. Co-operative banks can easily make usability much better without adding more features by making more sense of information grouping, increasing typography contrast, and simplifying the ways to get around. Figure 4 involves comparison of user trust and visual UX perception among banking platforms. Commercial banks invariably score more points in brand consistency, security confidence, professionalism, emotional comfort and total trust which means more mature design of interfaces and enhanced user confidence compared to co-operative banking systems.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Comparative Analysis of User Trust and Interface

Perception Across Commercial and Co-operative Banking Platforms

On the whole, the results support the idea that simplicity of interface and clearly defined information hierarchy are the core of the user friction reduction and its further involvement in digital banking setting. Digital trust is supported by robust and consistent branding and smooth-looking appearance by commercial banks. Co-operative banks hold relatively high trust levels because of institutional credibility whereas perceived professionalism in digital space is lower because of weaker visual consistency and outdated aesthetics.

6.4. Accessibility, Inclusivity, and Digital Literacy Considerations

The visual identity and trust perception indicate that commercial banks enjoy very consistent branding and modern interface aesthetics, which directly positively affect the perceived professionalism and confidence to trust it. The brand consistency and visual trust indicators are high, which is evidence of the strategic application of color, typography, and the use of the standardization of interaction patterns that strengthen the reliability.

Table 5

|

Table 5 Evaluation Results (%) |

||

|

Accessibility Parameter |

Commercial Banks (%) |

Co-operative Banks (%) |

|

WCAG Visual Compliance |

88.4 |

71.9 |

|

Readability Score (Fonts

& Contrast) |

90.2 |

78.6 |

|

Language Support Adequacy |

84.7 |

89.1 |

|

Elderly User Success Rate |

86.5 |

82.3 |

|

Digitally Novice User

Comfort |

79.6 |

85.4 |

|

Inclusive Design Score |

85.8 |

81.2 |

The co-operative banks, despite recording a slightly lower score in digital trust, have a relatively good overall trust perception owing to their years of presence and familiarity as an organization in the community. The reduction in emotional comfort score is not as large, which is supposed to indicate that the users are reassured by co-operative institutions even in the case of visual inadequacy. Nonetheless, less powerful interface professionalism and irregular branding lowers the digital trustworthiness of the co-operative sites, and especially with younger or urban-dwellers who correlate well-polished images with safety and competence. These results suggest that institutional reputation and visual communication determine trust in digital banking. Building visual identity by making the design systems consistent and providing enough security indicators can serve to make co-operative banks better convey their offline trust to digital trust. The standards of technical accessibility are dominated by commercial banks, whereas co-operative banks are more successful in the language familiarity and in the comfort of novice users. Nevertheless, ad hoc implementation of accessibility restrains inclusivity of co-operative digital systems and thus, designed visual accessibility models are required.

7. Conclusion and Future Research Directions

This paper has discussed how visual design thinking can influence online banking experience, and specifically how commercial banking and co-operative institutions can be compared to understand the influence of visual design thinking on online banking experiences. The most significant contribution of the research is proving that the visual design is not just an aesthetic layer, but a strategy that enables usability, trust, and inclusion of digital financial services. The systematic analysis of interface simplicity, visual identity, accessibility, and user experience can be used to identify how the design thinking concept can be applied in assisting co-operative banks to balance the two forms of banking: old-fashioned and relationship-based banking and the digital expectations of the present day. The results highlight that co-operative organizations have good intrinsic benefits in terms of community trust and familiarity of users, but have challenges on visual consistency, accessibility compliance, and efficiency of interface which can be successfully resolved with human-centered design solutions. An empirical validation and longitudinal research also has a definite scope in the study. The next steps to incorporate into future research are large-scale user testing, experimental testing, and longitudinal investigation of the patterns of digital adoption, the visual design interventions have a quantitative effect on trust, engagement, and operational efficiency. Longitudinal investigations would then be most welcome in the definition of how design changes in increments can affect user confidence and behaviour in the course of time, specifically in digitally vulnerable groups.

On the one hand, the future of the visual design thinking in digital banking is the increased attention given to inclusive design systems, adaptive interface, and ethical personalization. AI-guided UX analytics and contextual visual responses are some of the new technologies that can be used to make the experiences of users in the banking industry even more user-oriented. Finally, integrating; visual design thinking becomes a viable long-term sustainability approach to support co-operative banks in digitalizing and maintaining all their fundamental community values and promoting inclusive financial engagement.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Abraham, E., Ville, A., Ingalill, V., and Catrine, F. (2023). Exploring the Regulatory Demands and Evolution of Payment Security Regulations for Digital Payment Platforms in Sweden. Law and Economics, 2, 18–26. https://doi.org/10.56397/LE.2023.10.03

Alawaji, R., and Aloraini, A. (2025). Sentiment Analysis of Digital Banking Reviews Using Machine Learning and Large Language Models. Electronics, 14, 2125. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14112125

Alkhwaldi, A. F., Alharasis, E. E., Shehadeh, M., Abu-AlSondos, I. A., Oudat, M. S., and Bani Atta, A. A. (2022). Towards an Understanding of FinTech users’ Adoption: Intention and E-Loyalty Post-COVID-19 from a Developing Country Perspective. Sustainability, 14, 12616. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912616

Al-Qudah, A. A., Al-Okaily, M., Alqudah, G., and Ghazlat, A. (2024). Mobile Payment Adoption in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Electronic Commerce Research, 24, 427–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-022-09577-1

Amiri, M., Hashemi-Tabatabaei, M., Keshavarz-Ghorabaee, M., Antucheviciene, J., Šaparauskas, J., and Keramatpanah, M. (2023). Evaluation of Digital Banking Implementation Indicators and Models in the Context of Industry 4.0: A Fuzzy Group MCDM Approach. Axioms, 12, 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms12060516

Chen, J. (2024). FinTech: Digital Transformation of Financial Services and Financial Regulation. Highlights in Business, Economics and Management, 30, 38–45. https://doi.org/10.54097/512jkg86

Gaviyau, W., and Godi, J. (2025). Emerging Risks in the Fintech-Driven Digital Banking Environment: A Bibliometric Review of China and India. Risks, 13, 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13100186

Indrasari, A., Nadjmie, N., and Endri, E. (2022). Determinants of Satisfaction and Loyalty of E-Banking Users During the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Data and Network Science, 6, 497–508. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.ijdns.2021.12.004

Michailidis, P. D. (2024). A Comparative Study of Sentiment Classification Models for Greek Reviews. Big Data and Cognitive Computing, 8, 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc8090107

Negrea, C. I., Scarlat, E. M., Horătău, I., and Manta, O. (2025). Governing Financial Innovation Through Institutional Learning: Lessons from Romania's Fintech Innovation Hub. FinTech, 4, 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/fintech4040067

Persia, F., and D’Auria, D. (2017). A Survey of Online Social Networks: Challenges and Opportunities. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Information Reuse and Integration (IRI 2017) ( 614–620), San Diego, CA, USA. https://doi.org/10.1109/IRI.2017.74

Pluskota, P., Słupińska, K., Wawrzyniak, A., and Wąsikowska, B. (2025). The Design of Informational and Promotional Messages by cOoperative Banks and their Perception Among Young Consumers: An Eye-Tracking Analysis Versus Conscious Identification Based on Empirical Research. Applied Sciences, 15, 9635. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15179635

Polasik, M., Butor-Keler, A., Widawski, P., and Keler, G. (2024). Evaluating the Regulatory Approach to Open Banking in Europe: An Empirical Study. Financial Law Review, 34, 59–90. https://doi.org/10.4467/22996834FLR.24.007.20612

Scarlat, E. (2022). Regulation of Innovation in the Financial Sector. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Economic Scientific Research: Theoretical, Empirical and Practical Approaches (November 24–25, 2022), Bucharest, Romania.

Suryawanshi, S., Chaudhari, G. N., and Lokare, A. (2024). Strengthening IT Security in the Card and Payments Industry: Innovations in Fraud Prevention, Data Protection, and Regulatory Compliance. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, 22, 2285–2300. https://doi.org/10.30574/wjarr.2024.22.2.0185

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.