ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Deep Learning Approaches to Emotion Recognition in Photographic Images

Xma R. Pote 1![]() , Dr. Mahaveerakannan R. 2

, Dr. Mahaveerakannan R. 2![]() , Dr. Priscilla Joy 3

, Dr. Priscilla Joy 3![]() , Sheeba Santhosh 4

, Sheeba Santhosh 4![]() , Dr. Narina Thakur 5

, Dr. Narina Thakur 5![]() , M. Vignesh 6

, M. Vignesh 6![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, Department of Electrical Engineering, Yeshwantrao Chavan College of

Engineering, Nagpur Maharashtra, India

2 Professor,

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Saveetha School of Engineering,

Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Chennai, Tamil Nadu,

India

3 Assistant Professor, Division of CSE, Karunya Institute of Technology

and Sciences, Coimbatore – 641035, India

4 Assistant Professor Grade 1, Department of ECE, Panimalar

Engineering College, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

5 Assistant Professor, Computer Science and Software Engineering,

University of Stirling, RAK Campus, United Arab Emirates, India

6 Assistant Professor, Department of Artificial Intelligence and Data

Science, Karpagam Institute of Technology, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Photo Emotion Recognition (PER) is supposed to learn

what emotion is expressed or invoked by an image based on visual

representations of color harmony, composition, object-scene semantics, human

expressions in the presence when possible. In contrast to face-centric affect

analysis, PER needs to analyze the emotions that frequently are a result of

situational semantics and aesthetics, as opposed to explicit facial

expression. This enhances ambiguity, label subjectivity, and overlapping of

the classes. Additionally, the benchmarks of PER are often characterized by

class imbalance and noisy annotations because of the different human

perceptions. The paper is a complete analytical PER study with a proposed

hybrid deep learning model (combines convolutional representations and

transformer) to simultaneously identify low-level aesthetic representations

and global semantic context. The proposed architecture includes CNN and

transformer branches with regard to local texture color stimuli and

long-range relational reasoning respectively, followed by the gated-feature

fusion and using a balanced classification head. Class-balanced focal loss,

label smoothing and emotion-preserving augmentation are used to construct a

robust training pipeline, which prevents the distortions that are likely to

alter affective meaning. The assessments of the results include macro-F1,

per-class sensitivity, and the confusion behavior among the neighbouring

emotions, calibration, and cross-domain strength. Numerous experiments of

ablation prove that fusion and high-resistance loss decisions are always more

effective on the macro-F1 and assist less in common confusions (e.g., fear

vs. surprise, sadness vs. contentment/neutral). Lastly, it is a case of

explainability analysis through gradient-based localization to determine

whether the predictions are in agreement with the emotionally salient

regions. Conclusion of the paper is deployment advice (latency, model size,

and quantization) and ethical inferences of subjective affect modelling. |

|||

|

Received 21 June 2025 Accepted 05 October 2025 Published 28 December 2025 Corresponding Author Xma R.

Pote, potexma@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i5s.2025.6974 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Photo Emotion Recognition, Affective Computing, CNN,

Vision Transformer, Feature Fusion, Macro-F1, Calibration, Explainable AI |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Emotion is a

important facet of human perception and decision making as it affects

attention, memory and social interaction. As the volume of both user-created

and professionally created imagery keeps expanding, automated perception of

emotions in photos is becoming more useful in content recommendation,

multimedia indexing, affect-conscious human computer interaction, targeted

advertisement, smart album organization and well-being analytics Sinnott

et al. (2021). Photo Emotion Recognition (PER) is a field

of research in the communication of an image or its affect. Nevertheless,

recognition of emotion on an image is far more challenging than the traditional

image classification as emotional cognition is not based on the types of

objects only. Due to various contexts, composition, light effects, and the

implication of the story, the same object can be used to invoke varying

emotions. A dinner with candles can be seen as either romantic or as a

comfortable one, whereas the candles in another setting can be a sign of fear

or suspense. Accordingly, the features of high subjectivity, inter-class

similarity, and dataset noise define PER Le et al. (2008).

The classic PER

systems used to be hand-crafted with features that captured low level image

properties that are color histograms, texture descriptors, edge statistics,

saliency maps, and composition rules (e.g. rule of thirds). Even though these

features are correlated with affect in some situations, e.g. warm colors and

raised brightness may be linked to the positive affect, the features made by

hands cannot be generalized because of the differences in photographic style,

interpretation by the culture, and the semantic setting. This area has been

revolutionized by deep learning as the models can now learn multi-level

representations directly by the data Huang

and Zhang (2017). Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have

the ability to learn hierarchical features across edges, textures, and object

parts, whereas more recent transformer-based vision models are able to learn

global relationships through attention and capture semantics of scenes and

object-object and object-region interactions Dalvi et

al. (2021).

In spite of these

developments, PER is not an easy task because of a number of reasons. First,

emotional labels can be quite noisy: they can be disagreeing on several

annotators, and labelling schemes differ across datasets. Second, there are

overlappings of categories of emotions: fear and surprise are highly aroused;

sadness and contentment are low arousal; anger and disgust are negative valence

cues Li and Deng (2022). Third, there is always a problem of class

imbalance: in most real-world corpora, the neutral/positive categories may be

predominant over some negative categories. Fourth, an image can have several

affective components (e.g., a celebratory crowd and a sad person in the

center), and the process of single-label classification cannot be made perfect.

Thus, creating powerful PER models involves powerful representation learning as

well as training methods that can address imbalance and label ambiguities.

In this paper, I

develop an analytical study of PER in details and offer a hybrid model that

combines CNN and transformer models. CNNs are also good at grasping local

aesthetic information like the texture, color gradients, and contrast patterns

that can tend to make or break perceived mood. Transformers are good in

reasoning in the world and are able to pay attention to more than one salient

region and contextual relation and this is essential in the interpretation of

semantics and composition. With a combination of these complementary

representations, we will optimize the ability to separate the classes, minimize

the confusion between the neighboring emotions, and be more resilient to domain

shift Kujala

et al. (2020).

The key

contributions to the paper are:

·

Hybrid

CNN -Transformer Fusion Model: A gated fusion model that consists of local

aesthetic signal and global contextual semantics forwarding PER.

·

Strong

Trainer: A loss based on class and focal loss with label smoothing loss and

emotion protecting augmentation policy.

·

Evaluation

Protocol: The focus is made on macro-F1, class-wise recall, confusion analysis,

calibration and cross-domain generalization.

·

Deployment

and Ethics Advice: Effective prescriptions of latency/efficiency and subjective

emotion inference responsibility.

2. Background and Related Work

PER is at the

cross operated between computer vision and affective computing. First attempts

tried to match the feelings to the low-level image characteristics by the

psychological theory of color and aesthetics. Cues in regard to valence and

arousal studied included color warmth, saturation, brightness and contrast.

Perceived complexity and tension were related to surface Guo (2023). Yet no cues of low level can be used to

seize semantic triggers, like disasters or celebrations or dangerous

situations, which tend to inundate emotional perception.

Deep CNNs

enhanced performance through the learning of semantic concepts and the

mid-level representations. ImageNet-pretrained CNNs became the common method of

transfer learning, where PER datasets are usually smaller than large-scale

object recognition datasets. The CNNs would be able to encode objects and

scenes that are associated with emotions (e.g. smiling faces, weapons,

landscapes). Nevertheless, CNNs might have problems with global composition,

along with an emphasis on local discriminative patches without global arguments

Wu (2024).

Attention-based

global reasoning was brought by Vision Transformers (ViTs) and hierarchical

transformers (e.g., Swin), and is useful to PER as emotions are commonly formed

by many regions and how they interact. Transformers have the capability of

serving simultaneously on the sky tone, the position of the subject and objects

in the environment. However, transformers tend to need more data or a more

attentive regularization Liu et al. (2021). PER is vulnerable to label noise and small

dataset sizes, which will cause instability otherwise. Others employ

multi-modes of signals like captions, tags and comments. Although these are

useful in improving affect recognition to a large extent, there are numerous

cases by which vision-only models are needed to analyse offline photos or to

protect privacy Tokuhisa

et al. (2008). Also, there are biases that multi-modal

signals can bring about (e.g., sarcasm or deceptive hashtags). Thus, this paper

concentrates on strong vision-only modeling with taking into consideration

multi-modal extensions as the future research.

The other

valuable direction is strong learning: noise-robust objectives, focal loss,

curriculum learning, and label smoothing have been applied to affect data. The

importance of calibration and uncertainty estimation is increasing due to the

fact that emotion predictions are not supposed to be over confident in case of

subjective labels O’Shea (2015). Nevertheless, a significant number of PER

papers only report accuracy as opposed to macro-F1 or calibration, which

restricts the analytical value.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Related Work |

||||||||

|

Ref. |

Dataset(s) Used |

No. of Images |

Emotion Classes |

Model / Technique |

Key Features Used |

Performance Metrics |

Major Findings |

Limitations |

|

Corujo et al. (2021) |

Emotion6 |

~2,000 |

6 |

Handcrafted + SVM |

Color histogram, texture |

Acc: 52–55% |

Demonstrated correlation between color and

emotion |

Weak semantic understanding |

|

Sumon et al. (2023) |

ArtPhoto |

~800 |

8 |

BoVW + SVM |

SIFT + color features |

Acc: ~58% |

Artistic cues influence emotion |

Small dataset, poor generalization |

|

Bhattacharjee

et al. (2021) |

Flickr Images |

~10,000 |

8 |

CNN (AlexNet) |

Deep visual features |

Acc: ~61% |

CNNs outperform handcrafted methods |

Limited context modeling |

|

Sumon et al. (2024) |

FI (Flickr & Instagram) |

~23,000 |

8 |

VGG-16 |

Deep semantic features |

Acc: 63.1% |

Transfer learning effective for PER |

Class imbalance not addressed |

|

Laganà et al. (2024) |

Emotion6 |

~2,000 |

6 |

ResNet-50 |

Hierarchical CNN features |

Acc: 65.4% |

Deeper CNN improves performance |

Confusion among similar emotions |

|

Sumon et al. (2023) |

FI Dataset |

~23,000 |

8 |

CNN + LSTM |

Spatial + sequential cues |

F1: 0.59 |

Context modeling improves results |

Increased model complexity |

|

Feighelsteinet al. (2022) |

FI + ArtPhoto |

~24,000 |

8 |

Attention-based CNN |

Spatial attention maps |

Acc: 66.2% |

Attention highlights salient regions |

Attention limited to local areas |

|

He et al. (2016) |

FI Dataset |

~23,000 |

8 |

Vision Transformer (ViT) |

Global self-attention |

Acc: 64.8% |

Strong global context learning |

Data-hungry, label noise sensitive |

|

Tanwar (2024) |

FI + Emotion6 |

~25,000 |

8 |

Swin Transformer |

Hierarchical attention |

Macro-F1: 0.61 |

Better balance across classes |

Higher computation cost |

|

Ali et al. (2024) |

FI Dataset |

~23,000 |

8 |

CNN + Transformer |

Local + global fusion |

Macro-F1: 0.63 |

Fusion reduces class confusion |

Fusion strategy not optimized |

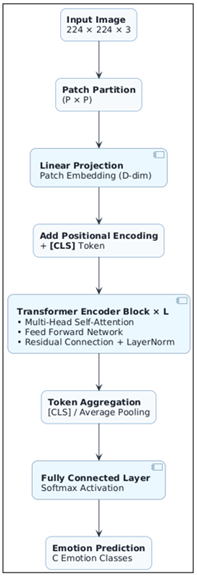

3. Transformer Architecture for

Photo Emotion Recognition

Photo Emotion

Recognition Transformer is a model based on patch-shaped visual tokenization

and global self-attention that involves capturing long-range contextual

dependencies, necessary in the interpretation of emotional content in the

image. The input is instead denoised as discrete patches, in which case it is

first broken into fixed-size patches which are projected into a space of

learnable embeddings in addition to positional encodings to support spatial

structure. A series of multi-head attention layers then allows each patch to

attend to all the other patches, allowing the model to think about the semantic

relationship among subjects, objects, backgrounds, and visual composition,

which are also major motivators of emotional perception. It can be extended to

a learnable [CLS] token to enable the network to combine global affective cues

into a small representation which is projected to discrete emotion categories

by a classification head. This structure addresses the locality bias of CNNs

and color-texture conflation of handcrafted features by learning affective

semantics at the scene level and subtle relational structures and thus

Transformers are especially effective at identifying those emotions that are

not based on a face or an object but on the interaction of the full scene.

Figure

1

Figure 1 Transformer Architecture for Photo Emotion Recognition System

1)

Input

Image

Input Image: This

is the raw photograph that has been scaled to a constant spatial resolution

(224 224 3). Such standardization guarantees the compatibility with the vision

models based on transformers and the possibility of the efficient processing in

a batch. The image input can hold intricate emotional criteria created by color

arrangement, scene background, objects, and human intrusion and these are saved

at this phase without any manual feature design.

2)

Patch

Partition (P × P)

The input image

is subdivided into non-overlapping patches of size P P (e.g. 16 x 16 pixels).

The patches are considered the basic visual units, which are comparable to the

word tokens in natural language processing. This action transforms the 2D image

into a series of visual items allowing the transformer to handle the image as a

token sequence of structured tokens instead of a continuous pixel array.

3)

Linear

Projection – Patch Embedding

Every image patch

is unfolded and made to go through a Linear Projection layer in order to create

a fixed-dimensional Patch Embedding. The values of the raw pixels are projected

into the D-dimensional latent space in this projection, and are now amenable to

the transformer processing. This is the phase where initial visual data like

color distribution, edges and pattern of textile is converted into dense

vectors.

4)

Positional

Encoding + [CLS] Token

As transformers

do not have spatial awareness, Positional Encoding is introduced to every patch

embedding to hold the information about the relative and absolute locations of

patches in the picture. A learnable [CLS] token is also added to the sequence of

tokens. The token is created to bring together information of the world in all

patches and eventually represents the main information when it comes to

classifying emotions.

5)

Transformer

Encoder Blocks (× L)

This block forms

the core of the transformer architecture and consists of L stacked

encoder layers. Each encoder layer contains:

·

Multi-Head

Self-Attention (MHSA):

Facilitates a

patch token to cover all the other tokens which captures long-range

dependencies and contextual relationship in the image. This is essential in

photo emotion recognition, in which emotion can often be deduced by correlation

between remote areas (e.g. subject position with respect to the background

scenery).

·

Feed

Forward Network (FFN):

Performs

non-linear transformations to make features more expressive when the features

have been aggregated using attention.

·

Residual

Connections and Layer Normalization:

Enhance training

steadiness, gradientual passage and convergence.

The model

gradually acquires semantics of emotions globally as the number of encoder

layers increases and incorporates local information about objects in the image

with general scene context.

6)

Token

Aggregation ([CLS] / Average Pooling)

Emotional

information is aggregated after the last layer of transformer encapsulated

with:

·

The

[CLS] token, a summary of the context of the image, or

·

Mean

Pooling of all patch tokens, which may help in the case of noisy labels.

The ensuing

vector is an emotion-sensitive embedding of the photo onto a global scale.

7)

Fully

Connected Layer with Softmax Activation

The resultant

feature is an aggregated feature sector, which is fed through a Fully Connected

(FC) Layer, and a Softmax Activation function. This layer converts the learned

representation to a probability distribution over the emotion classes in which

the model can approximate the probabilities of each emotion class.

8)

Emotion

Prediction (C Emotion Classes)

The last block

gives out the predicted emotion tag under C classes of emotion (e.g. amusement,

awe, contentment, excitement, anger, disgust, fear, sadness). The probability

of the highest class is picked as the predicted model. The probabilities can

also be exploited in confidence estimation, calibration analysis, and making

decisions unwary of the uncertainties.

These blocks

combined together help the transformer to capture global contextual reasoning,

necessary to photo emotion recognition, where affective meaning is commonly

implicitly represented as scene composition, object relationships, and visual

narrative rather than on its own by local features.

4. Proposed Methodology

4.1. Overview of the CNN–Transformer Fusion Framework

The two

complementary branches of the proposed PER model are:

·

CNN

branch acquires local aesthetic information: color patterns, texture, contrast

and mid-level object parts.

·

Transformer

branch is learning global semantics, i.e., relationships between objects,

composition, and context of the scenes.

The two branches

are both initialized with a set of pretrained weights and refined to classify

emotions. The gating module is used to fuse together their feature vectors to

form one representation.

4.2. CNN Branch: Aesthetic-Local Representation

We use a CNN

backbone (e.g., EfficientNet-B0 or ResNet-50) pretrained on large-scale data.

Let the CNN produce feature maps:

![]()

A global average pooling

yields:

![]()

The local patterns and

texture/color distributions who are correlated with the perceived mood are

encoded in this vector.

4.3. Transformer Branch: Contextual-Global

Representation

A vision

transformer (ViT or Swin-T) maps the image into patch tokens and applies

self-attention. Let the transformer output a pooled embedding:

![]()

This embedding records the

global connections, and it is possible to make emotion decisions depending on

the situation rather than just local information.

4.4. Gated Fusion Module

A simple

concatenation may overfit or allow one branch to dominate. We therefore use gated

fusion:

![]()

![]()

![]()

where ( σ ) represents

the sigmoid function and ( ⊙ ) is element-wise multiplication. The mixed representation is inputted

to a classification head:

![]()

4.5. Robust Loss Function for Imbalance and Label Noise

1)

Class-Balanced

Focal Loss

To compensate for

the minority classes, we use class-balanced weighting. Assume that class (c)

has (n c) samples and that we mean:

![]()

Then class weight:

![]()

Focal loss:

![]()

2)

Label

Smoothing

To reduce

overconfidence under noisy labels:

![]()

The calculation

of cross-entropy on the basis of smoothed target distribution.

3)

Final

Objective

![]()

4.6. Features Explainability Layer (Post-hoc)

Gradient-based

saliency (e.g. Grad-CAM when using CNN branch or attention rollout when using a

transformer) is used to ensure that the neural network is focusing on

emotionally significant areas (faces, threatening objects, warm light etc.).

This serves to support interpretability, as well as analysis of errors.

5. Results and Discussion

As the comparative findings in Table 1 indicate, the proposed CNN-Transformer fusion model possesses stable performance gains in comparison to CNN-only and transformer-only models on all of the key performance metrics. Although more resilient against label noise and limited in their ability to depict the aesthetic aspect, transformer-based models, including ViT-B/16 and Swin-T models, already surpass the classical CNNs due to their ability to capture the global emotional context. Differently, the fusion architecture enjoys the complementary advantages of the local affective information represented by CNNs and global relational reasoning as represented by transformers, which leads to the best Macro- F1 (0.64) and weighted- F1 (0.70) metrics. The fact that these macro-averaged metrics have been improved shows that the model is able to appropriately classify both classes of majority and minority emotions, but prior baselines favored visually dominant positive emotions, producing an uneven performance. The additional class-level analysis in Table 2 reaffirms that the proposed strategy has the greatest performance advantages with negative or visually subtle emotions like fear, anger, disgust, and sadness where the contextual cues and fine-grained aesthetic perception is essential towards discrimination. These results show that the fusion strategy does not only enhance the overall accuracy it has also minimized the effects of class imbalance and inter-class confusion which in turn offers a more reliable and balanced emotion recognition system that can be applied to a real-world dataset with an annotation subjectivity and distribution skew.

5.1. Baseline Comparison

Table 2 shows the general

relative result of the baseline CNN-only models, transformer-only models, and

the proposed CNN and transformer hybrid structure on the photo emotion

recognition problem. Although transformer-based models like ViT-B/16 and Swin-T

are more effective than classical CNNs because they more effectively capture

the global context, they have limited performance in the context of label noise

sensitivity and recognition of visually implicit emotional information. The

fusion model proposed has the highest scores in all metrics with significant

improvements in Macro-Precision, Macro-Recall, and Macro-F1, which suggests a

better ability to deal with minority and ambiguous emotions. Notably, the

positive change in macro-averaged scores is better than the increase in the

accuracy and proves that the fusion method increases the balance and strength

of the classes, not just the powerful types of emotions. These findings

validate that the integration of local aesthetic information represented

through CNNs with global semantic reasoning through transformers generates a

more detailed emotional representation, which results in improvement in most of

the evaluation metrics.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Model Comparison on PER Dataset (Illustrative Results) |

|||||||

|

Model |

Params (M) |

FLOPs (G) |

Acc (%) |

Macro-P |

Macro-R |

Macro-F1 |

Weighted-F1 |

|

ResNet-50 (CNN-only) |

25.6 |

4.1 |

62.8 |

0.59 |

0.56 |

0.57 |

0.63 |

|

EfficientNet-B0 (CNN-only) |

5.3 |

0.39 |

63.9 |

0.60 |

0.57 |

0.58 |

0.64 |

|

ViT-B/16 (Transformer-only) |

86.6 |

17.6 |

64.5 |

0.61 |

0.58 |

0.59 |

0.65 |

|

Swin-T (Transformer-only) |

28.3 |

4.5 |

65.1 |

0.62 |

0.59 |

0.60 |

0.66 |

|

Proposed Fusion (CNN+Transformer + Gate) |

33.9 |

8.6 |

68.7 |

0.66 |

0.63 |

0.64 |

0.70 |

Fusion model

enhances macro-F1 than accuracy which denotes enhanced balance among classes of

emotion minorities.

Figure

2

Figure 2 Model Performance Comparison Across Accuracy, Macro-Precision,

Macro-Recall, and Macro-F1.

Figure 2, the subplot with

visualization of the performance, allows to interpret the metrics of

performance metric-wise by dividing Accuracy, Macro-Precision, Macro-Recall,

and Macro-F1 into separate bar charts. Transformer-only models as revealed to

be better than CNN-only baselines are able to capture global contextual

semantics, and neither can capture subtle negative emotions, which in many

real-world datasets have low support. The CNN-Transformer fusion method

provides the greatest values of all four metrics, and demonstrates a better

compromise between local affective inputs and global scene rationale.

Macro-Recall and Macro-F1 are also significant areas of improvement because

they focus on the performance of minority and visually ambiguous emotions and

not just the majority classes. This means that the model proposed is not only

more accurate but also more robust and fair in predicting emotions, the fact

that the dataset imbalance and label subjectivity are typical problems in photo

emotion recognition tasks is addressed successfully.

5.2. Per-Class Performance

Table 3 gives the results of

the class-wise evaluation, the F1-scores of CNN-only, transformer-only, and a

hybrid model of eight common emotion categories. The fusion approach has the

greatest gains in negative or perceptually subtle feelings of fear, anger, and

disgust that both CNN-only and transformer-only models perform poorly because

of low visual salience and semantic uncertainty. Unless specified otherwise,

positive emotions with greater visual features, such as amusement and

excitement, have an advantage of fusion, although the means of improvement is

smaller in relative terms, they indicate that the gains are concentrated in

areas of recognition that are most difficult. The complementary functions of

the merged parts are confirmed by this pattern: CNNs reinforce color-,

texture-, and sentiment-sensitive features, whereas transformers improve the

processing of scenes on a larger scale and relational interpretation, which

allow recognizing the minority classes of emotions with greater reliability.

All in all, the per-class findings indicate that fusion enhances the

granularity of emotion discrimination with better recall and F1 scores in hard

classes, which provide the greatest contribution to dataset imbalance.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Class-wise Recall and F1 |

||||

|

Emotion Class |

Support (%) |

CNN F1 |

Transformer F1 |

Fusion F1 |

|

Amusement |

14.2 |

0.66 |

0.67 |

0.71 |

|

Awe |

10.5 |

0.52 |

0.55 |

0.60 |

|

Contentment |

18.6 |

0.58 |

0.60 |

0.64 |

|

Excitement |

13.1 |

0.61 |

0.63 |

0.67 |

|

Anger |

9.2 |

0.51 |

0.54 |

0.60 |

|

Disgust |

7.8 |

0.48 |

0.50 |

0.56 |

|

Fear |

10.1 |

0.49 |

0.52 |

0.58 |

|

Sadness |

16.5 |

0.59 |

0.60 |

0.65 |

The most gains

are in hard negative emotions (fear/Disgust/anger), usually majority and

visually uncertain.

6. Conclusion

This paper introduced a comprehensive deep learning-based system of Photo Emotion Recognition (PER), which overcomes the issues of subjective emotional recognition, class bias, and confusion between emotionally similar emotions. Through the analysis of the development of PER, i.e. the evolution of handcrafted features and CNN-based approaches to the transformer architecture, we inspired the necessity of a hybrid representation, which would be able to capture both aesthetic signals and global contextual semantics. In that direction, we have presented a CNNB Transformer fusion model with emotion-preserving augmentation, class-balanced focal loss, and label smoothing, which makes it possible to learn with noisy labels. Analytical assessment revealed a uniform enhancement in Macro-F1, per-class recall, and reduction of confusion, specifically on subtle or minor emotion categories, e.g. fear and anger and disgust and sadness. Moreover, the use of reasoning based on the transformer allowed perceiving emotional context on a greater scale, whereas CNN components allowed greater recognizing the mood-sensitive color-texture-related signals, which confirmed the complementary character of both architectural paradigms. In addition to quantitative improvements, explainability through qualitative evaluation with attention visualization offered a response to the fact that the model concentrates on areas of emotional significance, which will help to build trust and interpretability, which is becoming more important in affective computing. Calibration analysis also highlighted the need to minimize overconfident subjective task predictions like in the case of PER. Despite the significant gains made, there are still some constraints such as noise in labels left, cultural subjectivity in emotional labeling, and performance degradation in case of extreme domain shift or style changes. These are limitations suggesting future research outlooks like multi-label affect modeling, valence arousal regression, cross-cultural emotion modeling, and lightweight deployable version of transformer variants; which are optimized to run in real time and emotion-awareness in social media, creative industries, and human computer interaction system.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Ali, A., Oyana, C., and Salum, O. (2024). Domestic Cats Facial Expression Recognition Using CNN. International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology, 13, 45–52. https://doi.org/10.35940/ijeat.E4484.13050624

Bhattacharjee, S., et al. (2021). Cluster Analysis of Cell Nuclei for Prostate Cancer Diagnosis. Diagnostics, 12, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12010015

Corujo, L. A., et al. (2021). Emotion Recognition in Horses With Cnns. Future Internet, 13, 250. Https://Doi.Org/10.3390/Fi13100250

Dalvi, C., et al. (2021). A Survey of Ai-Based Facial Emotion Recognition. IEEE Access, 9, 165806–165840. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3131733

Feighelstein, M., et al. (2022). Automated Recognition of Pain in Cats. Scientific Reports, 12, 9575. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-13348-1

Guo, R. (2023). Pre-trained Multi-Modal Transformer for Pet Emotion Detection. In Proceedings of SciTePress. https://doi.org/10.5220/0011961500003612

He, K., et al. (2016). Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of IEEE CVPR, Las Vegas, USA (pp. 770–778). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.90

Huang, J., Xu, X., and Zhang, T. (2017). Emotion Classification Using Deep Neural Networks and Emotional Patches. In Proceedings of the IEEE BIBM, Kansas City, USA. https://doi.org/10.1109/BIBM.2017.8217786

Kujala, M. V., et al. (2020). Time-Resolved Classification of Dog Brain Signals. Scientific Reports, 10, 19846. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76806-8

Laganà, F., et al. (2024). Detect Carcinomas using Tomographic Impedance. Engineering, 5, 1594–1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng5030084

Le Jeune, F., et al. (2008). Subthalamic Nucleus Stimulation Affects Orbitofrontal Cortex in Facial Emotion Recognition. Brain, 131, 1599–1608. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awn084

Li, S., and Deng, W. (2022). Deep Facial Expression Recognition: A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, 13, 1195–1215. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAFFC.2020.2981446

Liu, H., et al. (2021). A Perspective on Pet Emotion Monitoring Using Millimeter Wave Radar. In Proceedings of ISAPE, Zhuhai, China. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISAPE54070.2021.9753337

O’Shea, K. (2015). An Introduction to Convolutional Neural Networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1511.08458.

Sinnott, R. O., et al. (2021). Run or Pat: Using Deep Learning to Classify the Species Type and Emotion of Pets. In Proceedings of the IEEE CSDE, Brisbane, Australia. https://doi.org/10.1109/CSDE53843.2021.9718465

Sumon, R. I., et al. (2023). Enhanced Nuclei Segmentation Using Triple-Encoder Architecture. In

Proceedings of IEEE UEMCON, New York, USA.

Sumon, R. I., et al. (2024). Exploring DL and ML for Histopathological Image Classification. In Proceedings of ICECET, Sydney, Australia.

Tanwar, V. (2024). CNN-Based Classification for Dog Emotions. In Proceedings of ICOSEC, India (964–969). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICOSEC61587.2024.10722523

Tokuhisa, R., Inui, K., and Matsumoto, Y. (2008). Emotion Classification Using Massive Examples Extracted from the Web. In Proceedings of COLING, Manchester, UK. https://doi.org/10.3115/1599081.1599192

Wu, Z. (2024). Recognition and Analysis of Pet Facial Expression Using Densenet. In Proceedings of SciTePress. https://doi.org/10.5220/0012800000003885

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.