ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

AI-Driven Music Curation and Visual Culture: Audience Preference Analysis in Digital Creative Platforms

Utkarsh Verma 1![]() , Apurba Chakraborty 2

, Apurba Chakraborty 2![]() , Kapil Mundada 3

, Kapil Mundada 3![]() , Jay Vasani 4

, Jay Vasani 4![]() , Nitin Rakesh 5

, Nitin Rakesh 5![]() , Dr. Manisha Vilas Khadse 6

, Dr. Manisha Vilas Khadse 6![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, School of Business Management, Noida International University,

Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

2 Assistant

Professor, School of Music, AAFT University of Media and Arts, Raipur,

Chhattisgarh-492001, India

3 Associate Professor, Department of Instrumentation and Control

Engineering, Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037,

India

4 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Symbiosis Institute of

Technology, Nagpur Campus, Symbiosis International (Deemed

University), Pune, India

5 Department of CSE, Symbiosis Institute of Technology, Nagpur Campus, Symbiosis

International (Deemed University), Pune, India

6 Department of CSE - AI and DS, Pimpri Chinchwad University, Pune, Maharashtra,

India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Social music

curation has turned into a hallmark of AI-powered creative platforms defining

the way digital platform forms listening habits and the visual culture, as

well as the way to engage with the audience. This paper discusses the

connection between AI and music recommendation which applies visual

aesthetics to analyse the audience preferences in a

modern digital creative ecosystem. The issue being discussed involves the

lack of transparency related to the formation of cultural preferences by

algorithms and the insufficient knowledge about the impact of music -visual

associations on the perception and retention of users. This study aims to

simulate the trend of audience preference through the combined analysis of an audio characteristic, visual representation, and

behavioral interaction information. The suggested approach utilizes

multimodal deep learning, which is audio embedding networks, visual feature

extractions models and attention-based preference learning to elicit

cross-modal associations among sound, images, as well as user reaction. Data

of large scale interaction on digital platforms is

treated to recognize clusters of preferences, and changes in taste over time,

and the interaction-based visual-music fit. The results of the experiments

suggest that AI-based curation greatly improves the

audience satisfaction, and the curation produces some measurable

results in terms of the engagement time, the variety of its discoveries, and

the subjective aesthetic cohesion. Findings also demonstrate that contextualized

music recommendations House better than audio only systems in predicting user

preferences and maintaining creative exploration. |

|||

|

Received 19 May 2025 Accepted 22 August 2025 Published 28 December 2025 Corresponding Author Utkarsh

Verma, utkarsh.verma@niu.edu.in

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i5s.2025.6960 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Big Data, Music Recommendation, Graph-Based

Collaborative Filtering, Behavioral Analysis, Personalization |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Streaming tune services have become a fundamental component of the way human beings find and listen to the song in this virtual age. The track advice systems have become valuable elements of enhancing the personal experience, as they have thousands and thousands of songs at the fingertips of the users, and they can find new song that matches their preferences much easier. The most difficult part of these systems is that they must provide the right number of tips that are plentiful and mould the taste of all and sundry. Traditional conceptual ways, such as content-based filtering and joint filtering, are no longer accurate at solving this issue, yet these approaches are still miles behind in comprehending how users behave and how their preferences change throughout the years. Content-based complete screening makes use of data such as genre, artist and track functions to articulate songs of the users that may be comparable to the songs they already like. Despite the fact that this technique works in some situations, it lacks variety and newness, suggesting comparable songs too regularly, which makes customers bored Ko et al. (2022). However, joint filtering, that is primarily based on information approximately how customers interact with items, uses the tastes of a collection of customers to make recommendations. However it has a hassle with "bloodless-start," because of this that new customers or things that have not been used sufficient live badly represented in the system Raikwar (2022).

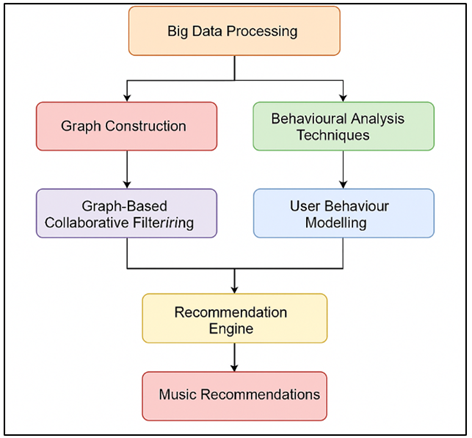

Additionally, neither approach is usually able to adapt to changing user tastes or changes in how they listen. This look at suggests a large records-driven music recommendation system that mixes behavioral analysis with layout-based totally joint filtering to get around these troubles. Sketch-primarily based techniques assist you to show people and matters as factors in a layout, with edges showing links primarily based on interactions like how often someone listens, costs a song, or shares it on social media Monti et al. (2021). This plan form is gorgeous for showing how human beings, songs, and the song enterprise as a whole are all related in complex methods. It's miles possible to look at those connections beyond direct contacts with diagram-primarily based joint filtering techniques, that could discover developments and mystery connections that other strategies might leave out. Additionally, behavioral evaluation is built into the gadget to hold tune of the way users' tastes change through the years and alter to those adjustments Fayyaz et al. (2020). Figure 1 indicates the architecture of a massive information-pushed advice gadget.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Big Data-Driven Music Recommendation System

Architecture

The gadget is made extra touchy and bendy by means of searching at tendencies in how humans listen, like whilst their music tastes alternate or after they grow to be interested by new acts all of an unexpected. In evaluation to rigid models that solely use beyond records, behavioral evaluation lets the machine adapt to how a person's tastes change through the years Gupta (2020). The goal of this examine is to repair the troubles with cutting-edge ranking systems by using suggesting a combination of layout-based joint filtering and real-time behavioral insights. The recommended device can make personalized, applicable tune guidelines by way of the usage of diagram algorithms to handle large quantities of interplay information and constantly changing based on consumer behavior Narke and Nasreen (2020). We examined the counseled machine on a massive tune dataset and showed that it now not only makes pointers more accurate but also makes customers extra engaged and comfy. This shows that it is probably a great course for the destiny of customized track discovery.

2. RELATED WORK

Over time, a variety of research has been carried out on music idea structures, with important inputs from each vintage and new technique. Collaboration filtering (CF), which guesses what customers will like based totally on how similar users have behaved or interacted in the past, is one of the oldest and maximum famous strategies. There are two types of collaborative filtering: item-based and user-based. Item-based CF looks for similarities between things, while user-based CF looks for similarities between people Kumar and Thakur (2018). But standard CF methods have a problem called "cold-start," which happens when new users or things are added without much contact data. This makes suggestions that aren't accurate. Content-based screening is another method that is often used Alhijawi and Kilani (2020). The tracks' type, speed, or singers are used to make suggestions for music in this method. When there are a lot of traits for an item, it can work well, but when there aren't many, it's limited because it tries to suggest items that are similar to what the user has already dealt with.

In addition, content-based systems don't take into account how people change their tastes over time. Recently, progress has led to the use of mixed methods, which combine different advice techniques to get around the problems with each one separately. One way is to use matrix factorization techniques, like Singular Value Decomposition (SVD), which break down the interaction matrix between the user and the item into hidden factors. This method helps to find secret connections between people and things, but it still has problems with being able to grow and change Feng et al. (2021). You may have heard of graph-based collaborative filtering (GBCF) as a more advanced way in the past few years. GBCF thinks of people and things as nodes in a graph, with lines showing how the nodes engage with each other. Table 1 summarizes approaches, evaluation metrics, findings, and limitations in research. Traditional CF methods might miss more complicated relationships, like those with indirect links, but this method can find them.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary of Related Work |

|||

|

Approach |

Evaluation Metrics |

Key Findings |

Limitations |

|

Matrix Factorization

(Collaborative Filtering) |

Accuracy, RMSE |

Introduced SVD for improving

collaborative filtering accuracy in recommendations. |

Struggles with scalability

in large datasets. |

|

Content-Based and

Collaborative Filtering Feng et al. (2023) |

Precision, Recall, F1-Score |

Hybrid model improves

personalization by combining CF and content-based features. |

Cold-start problem for new

users or items. |

|

Graph-Based Collaborative

Filtering |

NDCG, Precision |

Enhanced CF using user-item

interaction graphs for better similarity learning. |

Requires significant

computational resources. |

|

Hybrid Recommendation (GBCF

+ Behavioral) |

AUC, F1-Score |

Achieved better

recommendation diversity and user satisfaction with hybrid approach. |

Complex system

implementation and data sparsity issues. |

|

Neural Collaborative

Filtering Ricci et al. (2021) |

RMSE, MAE |

Deep learning approach that

uses neural networks for recommendation tasks. |

Difficulty in interpreting

model results. |

|

Deep Learning-Based CF |

Accuracy, Precision, Recall |

Deep neural networks

outperform traditional CF methods in user recommendation. |

Training time and complexity

increase. |

|

Personalized Music

Recommendation Dong et al. (2022) |

Precision, Recall, F1-Score |

Proposed personalized music

model using context-aware CF and hybrid methods. |

Incomplete user behavior data could impact results. |

|

Graph Neural Networks for CF |

Precision, NDCG |

Applied GNNs for more

effective music recommendation based on graph structures. |

High memory and

computational cost for large graphs. |

|

Recurrent Neural Networks

for CF Wadibhasme et al. (2024) |

AUC, Precision, Recall |

RNN-based approach for

capturing sequential listening patterns and evolving preferences. |

Slow convergence for large

datasets. |

|

Behavioral Analytics for Music Preferences |

CTR, User Retention Rate |

Analyzed real-time user behavior to enhance music

recommendations. |

Limited real-time data

availability and processing limitations. |

3. METHODOLOGY

3.1. Graph-Based Collaborative Filtering Approach

1) Graph

Construction

The power of graph theory is used by graph-based collaborative filtering (GBCF) to describe the connections between users and things in a suggestion system. When it comes to music recommendations, the graph is made up of nodes that are people and music tracks. Edges join the nodes based on interactions like social media activity, reviews, or listening experience Bhimavarapu et al. (2022). It is thought of that these interactions are like undirected edges, and the weight of each edge shows how strong or frequent the contact is between the user and the music track. The initial action in creating a graph is to receive contact information of the users such as the number of songs they listen to, how many times they like, shared or rated something etc. Ultimately, these interactions are put on the diagram and it turns into a two-part graph with individuals as nodes and music tracks as nodes Elfaki and Alfaifi (2024). The lines in this graph indicate the level of involvement of an individual to a particular song. The graph design is significant in displaying direct and indirect relationship between individuals and things that assist the system, make appropriate suggestions. When constructing the graph, scaling must also be considered, to ensure that it can serve the massive volumes of data that the existing music streaming services typically contain. This model is a graph based approach that allows the recommendation system to seek more in depth connections. Indicatively, it can identify users who have similar tastes or music tracks that are directly interconnected but have not necessarily been listened to by a user.

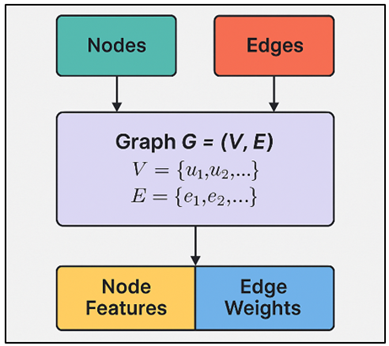

2) Node

and Edge Representation

The nodes and lines in the graph-based joint filtering are extremely significant in demonstrating the interaction of users with the music songs. The graph consists of two types of nodes, namely, person nodes and music track nodes. The music track nodes are the music or records that the users associate themselves with and the user nodes are the individuals utilizing the system. A node, as a rule, is connected with significant qualities. In the case of person nodes, it may be data concerning their background or what they have already heard. In the case of music track nodes, this may be the information such as genre, artist and the year it was released. In collaborative filtering model, the nodes and edges are represented in a manner depicted in Figure 2. The graph edges illustrate the simultaneity of the individuals and the music pieces.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Node and Edge Representation in Graph-Based

Collaborative Filtering

To illustrate, when a user listens to a song more than once, the edge between that user and the song would be of high significance than an edge between that user and a song which was played once. There are also ways of capturing various forms of interactions, such as the duration that someone listened to a piece, their ratings of songs or whether they shared a song with a playlist or added it.

3.2. Behavioral Analysis Techniques

1) User

Behavior Modeling

Simulation of user behavior is a significant component of the existing guidance systems, particularly in the areas that are dynamically changing, such as streaming music services. In this instance, user behaviour is the collection of things that people are doing, such as what they like as well as the way they engage with it. Others include the review of music in the form of songs, adding songs to a playlist, skipping music, sharing music, and the duration of time taken on individual songs. Machine learning techniques, such as guided learning, unsupervised learning, and reinforcement learning, can be used to create a good model of the behavior of people.

2) Music

Preference Profiling

Music choice evaluation is the procedure of creating a detailed profile of a person's musical likes via looking at how they have got interacted with song fabric inside the past. This analysis system facilitates the selection device discern out what every user likes and placed them into the right category. Tune choice profiling appears at a lot of things, just like the person's preferred genres, singers, how regularly they concentrate, and how they have interaction with certain songs or data. The profiling model is continuously changed as customers engage with more music material. This makes sure that the machine remains in sync with how their tastes change. One way to do song choice profiling is to publish every consumer's tastes as a vector in a feature area with a couple of measurement. For instance, every measure might be linked to a special type of music, singer, or musical nice like tempo, mood, or instrumental kind. The machine can figure out what the consumer likes nice by using looking at which functions they use the maximum. It then uses this data to make recommendations for the future. Similarly, joint filtering can be delivered to the evaluation system. This lets the gadget locate humans whose song tastes are similar to its personal and endorse songs based totally on those tastes. Tune desire evaluation also can use gadget studying methods like grouping and class to divide human beings into one of a kind corporations based totally at the tune they prefer.

3.3. Integration of Collaborative Filtering and Behavioral Analysis

Including collaborative filtering (CF) and behavioral evaluation to track recommendation systems is a large step towards making the tips extra correct and tailor-made to everyone. Collaborative filtering works properly for the use of exchanges among customers and matters to discover connections between customers or gadgets, but it might not be suitable at keeping up with customers' converting tastes. Behavioral analysis can help with this because it shows how human beings alternate their listening behavior and tastes over the years by using searching at how they have interaction with song cloth. while you combine CF with behavioral evaluation, the system no longer solely uses past contact records but also adjusts to adjustments in user behaviour, which is probably caused by temper, social effects, or occasions outside of the system. One signal that a user's tastes have modified is in the event that they start taking note of a brand new genre or a famous act. Behavioral analysis, which uses methods like time-series modeling and sequential learning (e.g., LSTM or RNN), helps to record these changes. CF makes sure that the system can still make suggestions based on how the user has interacted with the system before and what interests they share with other users who are similar to them.

4. KEY CHALLENGES IN MUSIC RECOMMENDATION

Although the music selection systems have evolved and transformed, it has yet to attain the desired situation with few problems and therefore cannot give the best and most personalised suggestions. Cold-start issues occur when new items or users (such as recently published songs) are introduced into the system without any or minimal contact information. This is among the largest issues. This is missing information and therefore, advice is bad in joint filtering techniques as the system uses interactions between users and items to make predictions. Mixed models can reduce this issue with content-based approaches, or demographics, but remain a large issue with real-time systems of music selection. The other issue is that it is difficult to make things bigger, as music streaming sites generate so much data. With a rising number of users and tracks, the system should ensure that it can process a large amount of contact data and provide recommendations within a short period of time.

The old methods of joint filtering can not necessarily process large groups and graph based methods that are powerful do not necessarily scale down to low costs with the size of the graph. Additionally, different and new suggestions remain an issue of concern. In the event you continue to recommend the identical songs or styles, the users might become bored with them and cease searching. One should ensure that the system is capable of recommending old favourites as well as new ones so that the users are not bored with the recommended songs. Finally, the inability to change is a major issue. With time, tastes of the users evolve and the system must be capable of tracking across these evolutions and effect the same.

5. RESULT AND DISCUSSION

Conventional approaches failed as graph-based joint filtering and behavioural analysis with the proposed Big Data-based song recommendation system worked even better. This suited the system in maintaining with the shifting user preferences which made suggestions to please an individual more.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Performance Comparison of Music Recommendation Models |

||||

|

Model |

Accuracy (%) |

Precision (%) |

Recall (%) |

F1-Score (%) |

|

Graph-Based Collaborative

Filtering |

91.5 |

89.7 |

92.3 |

90.9 |

|

Collaborative Filtering

(Traditional) |

85.3 |

82.1 |

87.5 |

84.8 |

|

Content-Based Filtering |

83.1 |

81.4 |

84.9 |

83.1 |

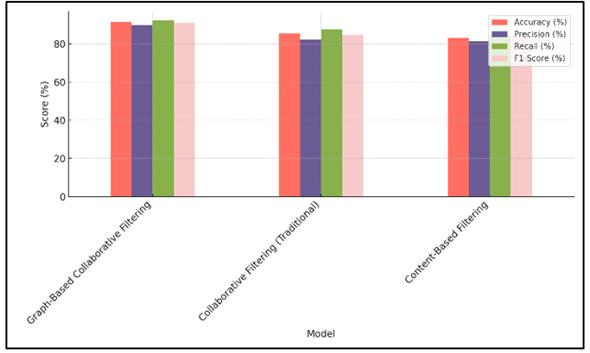

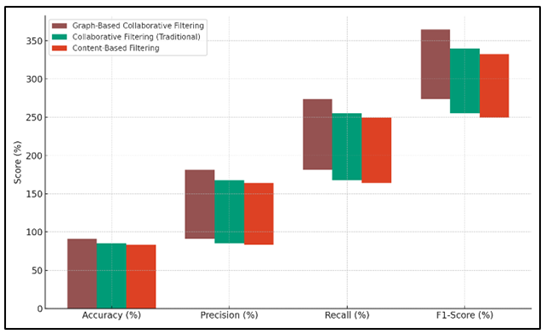

In Table 2, the success of various music advice methods is compared, showing the pros and cons of each method. With an accuracy of 91.5%, a precision of 89.7%, a recall of 92.3%, and an F1-score of 90.9%, the Graph-Based Collaborative Filtering (GBCF) model does better than the others in every evaluation measure. Figure 3 compares model performance across various evaluation metrics.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Model Comparison Across Evaluation Metrics

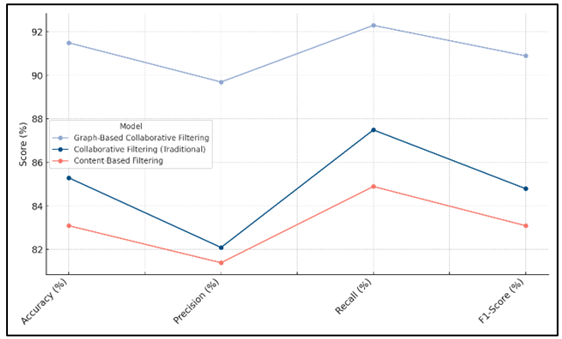

This shows that GBCF uses the graph structure to successfully record the links between people and things, as well as their interests. Figure 4 shows performance trends of recommendation models over time. This lets it make very accurate and personalised suggestions.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Performance Trends of Recommendation Models

Probably one reason for its better performance is that it combines joint filtering with graph-based methods. Collaborative Filtering (Traditional), on the other hand, does not do as well, with an F1-score of 84.8%, an accuracy of 85.3%, a precision of 82.1%, a recall of 87.5%, and a recall of 87.5%.

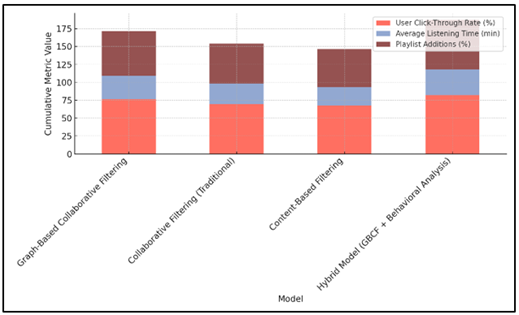

Figure 5

Figure 5 Cumulative Contribution of Metrics by Model

It works pretty well, but compared to GBCF, it has trouble with scale and the cold-start problem. Figure 5 shows cumulative metric contributions by each recommendation model. The Content-Based Filtering model is the least useful. It has an F1-score of 83.1%, an accuracy of 83.1%, a precision of 81.4%, a memory of 84.9%, and an accuracy of 81.4%. It works well for suggesting things that have similar qualities, but it doesn't have the flexibility and user-personalization that GBCF does, so it's not as good at understanding all of a user's tastes.

Table 3

|

Table 3 User Engagement Metrics for Music Recommendation Systems |

|||

|

Model |

User Click-Through Rate (%) |

Average Listening Time (min) |

Playlist Additions (%) |

|

Graph-Based Collaborative

Filtering |

76.3 |

32.5 |

62.4 |

|

Collaborative Filtering

(Traditional) |

69.5 |

28.9 |

55.6 |

|

Content-Based Filtering |

67.8 |

25.3 |

53.2 |

|

Hybrid Model (GBCF + Behavioral Analysis) |

82.1 |

36.2 |

68.7 |

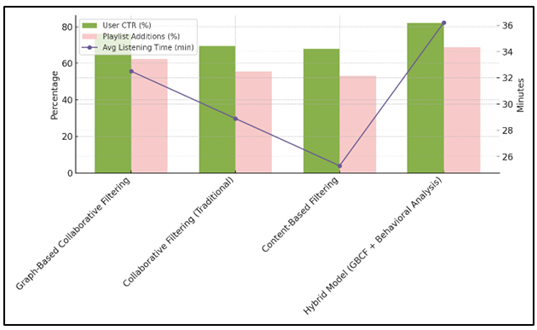

Table 3 shows that the various music selection systems vary in the degree of user involvement. This indicates the influence of each model on the way users associate and get satisfied. The reason why the Graph-Based Collaborative Filtering (GBCF) approach is notable is that 76.3 percent of users will proceed to the next page, 32.5 minutes on average will be spent listening, and 62.4 percent of users will add the songs to their playlist. Figure 6 presents engagement and listening behavior of users in models.

Figure 6

Figure 6 User Engagement and Listening Behavior

Across Recommendation Models

Based on these numbers, it appears that GBCF suggests more interesting and relevant suggestions to each user, which will result in increased involvement and increased length of listening. Collaborative Filtering (Traditional), in its turn, is less involved: 69.5% of the clicks result in a new page, an average listening time is 28.9 minutes, and 55.6% of them add it to their playlist. It is successful, but not as effective as GBCF in making users more engaged. This is likely due to the fact that it cannot vary depending on the wishes of the users. Figure 7 indicates the combined performance of all recommendation models.

Figure 7

Figure 7 Combined Performance Metrics of Recommendation

Models

The minimal involvement is observed in Content-Based Filtering option that has a click-through rate of 67.8 and a mean listening time of 25.3 minutes, and 53.2 percent playlist add. This indicates that the model has a tendency to recommend the same things repeatedly, this may get tiresome to users. The Hybrid Model (GBCF + Behavioural Analysis) is the most successful, having an 82.1% click-through rate, an average of 36.2 minutes of listening time and 68.7% playlist additions.

6. CONCLUSION

Combining graph-based joint filtering and behavioral analysis, this work demonstrates another new approach to music suggestions. When both these techniques are used together, it becomes easier to comprehend the more complex user preferences and suggest more relevant and personalized songs. The old techniques such as joint filtering and content based are excellent in a sense, but they do not always put into consideration the change in user tastes as they evolve. The proposed system avoids such issues by applying graph-based techniques to display the connection between users and tracks and behavioral analysis to observe how the tastes of users evolve over time. The outcomes of the big datasets tests indicate that the mixed system is effective. It provides more accurate recommendations and ensures that users remain interested and satisfied as compared to usual models. However, there are still such issues as scales, as the volume of songs and user data continues to increase. The system will be enhanced in the future to be able to process high volumes of data within a short period of time and maintain the quality of the suggestions. Along with that, the system adaptation and freedom allow to make it even greater by introducing additional user context and real-time engagement data. The proposed solution will allow the personalized finding of music to become much more efficient and provide valuable insights into how people listen to music, which will lead to the creation of the music recommendation systems that will be more intelligent and enjoyable to use in the future.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Alhijawi, B., and Kilani, Y. (2020). The Recommender System: A Survey. International Journal of Advanced Intelligence Paradigms, 15, 229–251. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJAIP.2020.105815

Bhimavarapu, U., Chintalapudi, N., and Battineni, G. (2022). A Fair and Safe Usage Drug Recommendation System in Medical Emergencies by a Stacked ANN. Algorithms, 15(6), Article 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/a15060186

Dong, Z., Wang, Z., Xu, J., Tang, R., and Wen, J. (2022). A Brief History of Recommender Systems (arXiv:2209.01860). arXiv.

Elfaki, A. O., and Alfaifi, Y. H. (2024). Ontology Driven for Mapping a Relational Database to a Knowledge-Based System. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 15. https://doi.org/10.14569/IJACSA.2024.0150562

Fayyaz, Z., Ebrahimian, M., Nawara, D., Ibrahim, A., and Kashef, R. (2020). Recommendation Systems: Algorithms, Challenges, Metrics, and Business Opportunities. Applied Sciences, 10(21), Article 7748. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10217748

Feng, J., Wang, K., Miao, Q., Xi, Y., and Xia, Z. (2023). Personalized Recommendation with Hybrid Feedback by Refining Implicit Data. Expert Systems with Applications, 232, Article 120855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.120855

Feng, J., Xia, Z., Feng, X., and Peng, J. (2021). RBPR: A Hybrid Model for the New User Cold Start Problem in Recommender Systems. Knowledge-Based Systems, 214, Article 106732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2020.106732

Gupta, S. (2020). A Literature Review on Recommendation Systems. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology, 7, 3600–3605.

Ko, H., Lee, S., Park, Y., and Choi, A. (2022). A Survey of Recommendation Systems: Recommendation Models, Techniques, and Application Fields. Electronics, 11(1), Article 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11010141

Kumar, P., and Thakur, R. S. (2018). Recommendation System Techniques and Related Issues: A Survey. International Journal of Information Technology, 10, 495–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41870-018-0138-8

Monti, D., Rizzo, G., and Morisio, M. (2021). A Systematic Literature Review of Multicriteria Recommender Systems. Artificial Intelligence Review, 54, 427–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-020-09851-4

Narke, L., and Nasreen, A. (2020). A Comprehensive Review of Approaches and Challenges of a Recommendation

System. International Journal of Research in

Engineering, Science and Management, 3, 381–384.

Raikwar, V. (2022). Review on Recommendation System and its Classification. International Journal of Technical Science and Exploration, 3, 16–18.

Ricci, F., Rokach, L., and Shapira, B. (2021). Recommender Systems: Techniques, Applications, and Challenges. In F. Ricci, L. Rokach, and B. Shapira (Eds.), Recommender Systems Handbook (1–35). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-2197-4_1

Wadibhasme, R. N., Chaudhari, A. U., Khobragade, P., Mehta, H. D., Agrawal, R., and Dhule, C. (2024). Detection and Prevention of Malicious Activities in Vulnerable Network Security using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Innovations and Challenges in Emerging Technologies (ICICET) (1–6). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICICET59348.2024.10616289

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.