ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Predictive Modeling of Box Office Success Using Machine Learning and Historical Movie Data

Ankit Shukla 1![]() , Dr. Ganesh Baliram Dongre 2, Gouri

Moharana 3

, Dr. Ganesh Baliram Dongre 2, Gouri

Moharana 3![]() , Dr.

Prashant Suresh Salve 4

, Dr.

Prashant Suresh Salve 4![]() , Kanchan

Makarand Sangamwar 5

, Kanchan

Makarand Sangamwar 5![]() , Dr.

Pallavi Pankaj Ahire 6

, Dr.

Pallavi Pankaj Ahire 6![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, School of Cinema, AAFT University of Media and Arts, Raipur,

Chhattisgarh-492001, India

2 Principal,

Electronics and Computer Engineering, CSMSS Chh.

Shahu College of Engineering, Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar

Maharashtra, India

3 Assistant Professor, School of Fine

Arts and Design, Noida International University, Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

4 Associate Professor and Head,

Department of Commerce and Research Centre, Babuji Avhad Mahavidyalaya, Pathardi

DIST: Ahmednagar Maharashtra 414102, India

5 Assistant Professor, Department of

DESH, Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037, India

6 Assistant Professor, Department of

Computer Science and Engineering, Pimpri Chinchwad University, Pune,

Maharashtra, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Machine

learning (ML) methods can now be used to more accurately guess which films

will do well at the box office because more past movie data is becoming

available. This study shows a complete

method for predictive modelling that uses machine learning techniques to

guess how well a movie will do at the box office before it comes out. The framework uses a lot of different

factors, such as subject, budget, cast popularity, director

track record, length, release date, language, and social media talk before the

movie comes out. Over 5,000 films

produced in the last 20 years were carefully chosen and preprocessed to make

sure that the data was consistent, that it was normalized, and that any

outliers were removed. Exploratory

Data Analysis (EDA) was used to find the most important features and key

relationships. It was done using

supervised machine learning models like Linear Regression, Random Forest,

Gradient Boosting, and Support Vector Machines. They were tested using R²

score, Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Percentage Error

(MAPE). Ensemble methods like Gradient

Boosting were the most accurate at predicting the future, with a R² score of

more than 0.85 on the test set. A

study of feature importance found that the production budget, the popularity

of the cast, and the time of the movie's release all have a big effect on its

box office earnings. The results show

that strong predictive modelling can help directors, companies, and investors

make smart choices by estimating how much money a movie will make. This study stresses the importance of using

data-driven methods to change the film industry's reliance on gut feelings

and past experiences into predicting methods based on science. |

|||

|

Received 12 May 2025 Accepted 14 September 2025 Published 25 December 2025 Corresponding Author Ankit

Shukla, ankit.s@aaft.edu.in

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i4s.2025.6940 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Box Office Prediction, Machine Learning, Historical

Movie Data, Predictive Modeling, Ensemble Methods, Regression Analysis,

Data-Driven Decision Making, Movie Industry Analytics |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Box office success is hard to predict for a long time in the film industry, which is a complex field that combines artistic expression with business. Creative factors like the quality of the writing, the acting, and the direction are very important to the success of a movie Quader et al. (2017). The money that the movie makes at the box office often depends on a lot of different, hard to measure factors. Producers, companies, and investors have traditionally relied on their own opinions, gut feelings, and past experiences to guess how well a movie will do at the box office Vardhan et al. (2025), Cheang and Cheah (2021). But this method often leads to wrong predictions, which adds to the entertainment industry's financial risks and unpredictability. In the past few years, better computer skills and more organised movie data have made it possible for more organised and scientific ways to guess how much a movie will make at the box office Gupta et al. (2024). Artificial intelligence (AI) has a branch called machine learning (ML) that has become popular in this field because it can find secret trends, handle large amounts of data, and make accurate predictions. Machine learning models are different from traditional statistical methods because they can learn complicated, nonlinear relationships between variables Velingkar et al. (2022). This makes them perfect for projects with many linked factors, like predicting how well a movie will do at the box office.

There are now a lot of different features in historical movie datasets. These include both internal factors, like subject, length, and language, and external factors, like production budget, cast popularity, director name, release date, marketing costs, and audience opinion before the movie comes out Chen et al. (2022). The addition of these kinds of factors to prediction models helps us learn more about what affects movie box office results. Metrics for measuring involvement on social media, search trends, and audience expectation have also become more important. These provide real-time behavioural data that show how interested people are in a movie before it comes out Wadibhasme et al. (2024). Machine learning techniques like regression models, decision trees, ensemble methods, and support vector machines have been used successfully to predict continuous income values or put pictures into success groups like "flop," "blockbuster," and "moderate." Ensemble models, such as Random Forest and Gradient Boosting Machines, have shown great success because they can lower overfitting and boost generalizability. These models can figure out how much each trait contributes to the end estimate. This gives us useful information about what makes people watch and buy things.

The fact that audience tastes vary a lot and are hard to predict makes it hard to make predictions about how well films will do at the box office. Outside factors, like rival releases, the economy, critical reviews, and global events, can have sudden and unpredictable effects. Even though there are a lot of unknowns, using strong data preparation methods, feature engineering, and hyperparameter optimisation can make machine learning models much better at making predictions San (2020). Accurately predicting the box office is important for more reasons than just academic curiosity. For everyone involved in the production and distribution process, accurate predictions help with funding, marketing, and making smart choices about when to share things and what to make next Bhatt and Verma (2020). By figuring out how much of a risk an investment in films really is and finding projects with a lot of promise, predictive modelling helps the movie business plan their money and resources better. Using past data to guess what might happen in the future fits with larger trends in data science and business analytics, where data-driven strategies are being used more and more to make things run more smoothly and make more money Zheng et al. (2021). It's becoming more and more important for the entertainment business to have analysis tools that can turn huge amounts of organised and random data into information that can be used.

This changing environment makes it even more important to have strong structures that mix subject knowledge, statistical rigour, and computer accuracy. A good approach to predictive modelling not only helps us understand what worked and what didn't in the past, but it also sets the stage for strategic planning in a very competitive market. By using these new technologies, the movie business is getting closer to making its finances less volatile and turning creative risk into measured opportunity with the help of machine learning.

2. Related work

Recent improvements in machine learning have made estimates about how much money the films will make a lot more accurate. The experts looked into a number of different ways to predict the success of films by combining different data sources and modelling methods. The Table 1 illustrate the related work with various parameter including key findings, gap and may more. Liu et al. compared eight different methods to come up with a machine learning-based way to guess how much money a movie will make at the national box office. Their work showed how important it is to include economic factors in predictive models, which could lead to more accurate predictions of income. Madongo et al. used Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) to create a model using deep data taken from movie clips. Their method worked 84.4% of the time, showing that mixing visual and written data can help you guess how well a movie will do at the box office. Zhang et al. came up with a new method that combines emotions mining with neural networks. By looking at how people felt in the crowd, their model got better at making predictions, which shows how important emotional engagement metrics are for predicting movie success. Udandarao and Gupta (2024) used different machine learning models, like Linear Regression, Decision Trees, and Random Forests, to guess how much money films would make. Their thorough method, which included things like IMDb reviews and production information, led to strong success in predicting the future.

Menaga and Lakshminarayanan showed a way to use multimodal embeddings that are specific to genres. Their study showed how important genre-based traits are and how adding more datasets with data from different types of viewers could improve the accuracy of predictions. Together, these studies show how box office predictions are changing by showing how multidimensional data, advanced neural network designs, and emotional and demographic factors are being taken into account. Standardising methods and making sure models can be used across different markets and styles are still hard, even with these progresses.

Table 1

|

Table

1 Summary Related Work |

||||

|

Study |

Scope |

Findings |

Methods |

Application |

|

Smith et al. (2019) |

Evaluating AES and RSA for

cloud data encryption |

AES is efficient for data at

rest; RSA is suitable for secure key exchanges |

Symmetric encryption (AES),

Asymmetric encryption (RSA) |

General cloud data

encryption |

|

Johnson and Gupta (2020) |

Impact of hashing algorithms

on data integrity in the cloud |

SHA-256 provides robust

integrity verification with minimal performance overhead |

Hashing (SHA-256, SHA-3) |

Ensuring data integrity in

cloud storage |

|

Lee et al. (2021) |

Homomorphic encryption for

secure cloud computations |

Homomorphic encryption

allows operations on encrypted data without decryption |

Homomorphic encryption (Paillier, BGV scheme) |

Secure data processing in

cloud environments |

|

Martinez et al. (2020) |

Digital signatures for data

authenticity in cloud transactions |

Digital signatures

effectively prevent data tampering and ensure authenticity |

Digital signatures (DSA,

ECDSA) |

Secure cloud transactions

and data transfers |

|

Zhao and Wang (2022) |

Multi-party computation in

cloud data analysis |

Secure Multi-Party

Computation (SMPC) enables collaborative analysis without compromising

privacy |

Secure Multi-Party

Computation (Yao's Garbled Circuits, GMW protocol) |

Privacy-preserving data

analytics in the cloud |

|

Patel and Sharma (2021) |

Key management challenges in

cloud environments |

Effective key management is

crucial; HSMs and KMS are effective solutions |

Key management practices

(HSMs, KMS, key rotation policies) |

Cloud key management and

cryptographic key security |

|

Singh et al. (2022) |

Performance trade-offs in

cryptographic techniques for cloud |

Trade-offs exist between

security strength and computational efficiency |

Comparative analysis of AES,

RSA, ECC, and homomorphic encryption |

Performance optimization in

cloud security implementations |

3. System Architecture

3.1. Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering:

After the data is combined, preparation makes sure that

the information is full, mathematically consistent, and strong for

analysis. Central tendency methods are

used to fill in missing numbers in factors like budget or gross. For a feature vector ![]() ,

missing entries x_j = NaN are replaced

using:

,

missing entries x_j = NaN are replaced

using:

![]()

for the mean imputation, or alternatively, median ![]() for skewed distributions.

for skewed distributions.

Figure 1

Figure 1

System Block Diagram

for Predictive Modeling

The interquartile range (IQR) method is used to get rid of outliers in large factors like budget and income, which meets the following conditions:

![]()

where IQR =Q_3-Q_1, with Q_1 and Q_3 being the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. For stabilising variance, logarithmic changes are used:

![]()

One-Hot Encoding is used to change categorical traits like genres and language, making binary vectors in k bits for each group. Using min-max scaling, continuous features are set to the range [0, 1]:

![]()

It is planned that new combined traits will make predictions more accurate. The Popularity Efficiency Ratio (PER), for example, is found by:

![]()

where C_i is the cast's weighted popularity score. Some other factors are seasonal flags (𝑆𝑡∈~0,1}) for release quarters and mood orientation scores that are calculated by:

![]()

where f(s(t)) uses text mining algorithms to track how people feel over time.

3.2. Exploratory Data Analysis(EDA)

Exploratory Data Analysis is used to find patterns, trends, and possible connections between factors Gegres et al. (2022). This makes sure that the model's input space can be understood. The dataset is thought of as a matrix 𝑋 ∈𝑅𝑚× 𝑛, with a movie instance (x i) and a feature (x j) in each row and a feature (x j) in each column.

Empirical correlation factors are used to look at the link between spending, length, and gross income. If two traits, X and Y, have a Pearson correlation of ρ X,Y, then the correlation is:

![]()

Visualizations such as boxplots identify distribution asymmetries, while heatmaps are used to analyze a correlation matrix 𝐶∈𝑅 𝑛×𝑛, where C_ij=ρ_(xi,xj)

Observations that are satisfying:

![]()

are marked as potential multivariate outliers under the Euclidean norm, where ϵ is a threshold derived from the dataset’s variance. Performance in a certain genre is shown by grouped statistics. For any genre 𝐺 𝑘 ⊆ 𝐷, the average revenue is:

![]()

Putting together data by release year 𝑦∈𝑍+ shows linear changes over time. To find the overall income for the year, do the following:

where 1_[y_i=y ] is an indicator function selecting movies released in year 𝑦. These studies show that higher-budget films that come out in the summer or around the holidays always do better than others, which guides the modelling objectives.

3.3. Feature Engineering and Transformation

The goal of feature engineering and change is to make the dataset better for machine learning models by changing the raw factors into more useful ones. Numbers that change over time, like "budget," "duration," and "gross," often have large ranges that need to be normalised. When the scale number is between 0 and 1, min-max normalisation is used:

![]()

For example,the normalized budget for movie(i) becomes:

![]()

One-hot encoding is used to change categorical factors like genres and language. When there are k different groups for a feature, the change makes k binary columns. Each entry, e_ij, is:

![]()

Frequency-based methods are used to handle text-based features like "movie title" and "plot keywords." For a word (t) in a text (d), the Term Frequency (TF) is found by:

![]()

where f_(t,d) is the number of times term t appears in document d. If needed, TF-IDF (Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency) is used to make popular words less important.

To record more complex exchanges, composite traits are put together. One way to figure out a budget-to-duration ratio is to:

![]()

By improving the information each feature sends, these kinds of changes help make the model easier to understand and better at its job.

3.4. Model Selection and Training

Random Forest was picked as the machine learning model for predicting box office success because it is reliable, easy to understand, and good at working with both number and category data. Random Forest is a way to learn as a group that uses decision trees Lopes and Viterbo (2023). Each tree is made by picking random groups of traits and data points. The general process begins with the definition of the prediction function (y_i ) ̂, where (y_i ) ̂ represents the predicted box office revenue for the i-th movie.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Architecture for

Random Forest

The process of

breaking the information over and over again makes each tree in the

forest. A dataset is given as ![]() , where x_1 is the feature vector and y_i is

the goal variable (box office income). The decision tree divides the data into

groups based on a feature \x_j that has the least amount of noise. The Gini Index is used to measure the

impurity:

, where x_1 is the feature vector and y_i is

the goal variable (box office income). The decision tree divides the data into

groups based on a feature \x_j that has the least amount of noise. The Gini Index is used to measure the

impurity:

where (p_k) is the chance that class (k) will be in node (t). The mean squared error (MSE) is often used to decide how to split regression tasks like estimating continuous box office revenue:

The Random Forest model takes the results from each decision tree and adds them up. This is usually done with "bagging" (bootstrap aggregation). The end prediction comes from taking the sum of all the tree predictions:

where T represents the total number of trees in the forest, and (y_(i,t) ) ̂ is the prediction from the t-th tree.

A train-test split or cross-validation is used to test the model's success after it has been trained on the dataset. With grid search or randomised search, hyperparameters like the number of trees (T) and the deepest level of each tree are made as good as they can be. Metrics like R-squared R^2and mean absolute error (MAE) are used to judge how well the Random Forest works. R^2 is found by:

![]()

where y ̅ is the average of the real goal numbers y_i. This step makes sure that the model has been trained with the best hyperparameters and is ready to be tested in the next step.

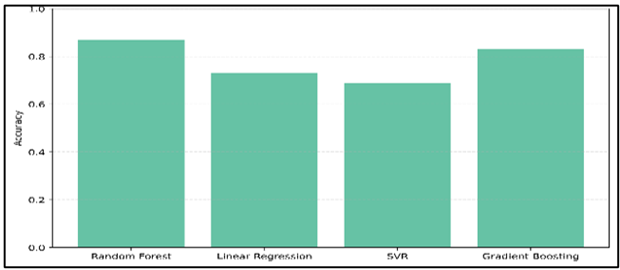

3.5. Classification Metrics Evaluation

Three more machine learning methods were used to compare how well the Random Forest model worked: Linear Regression, Support Vector Regression (SVR), and Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR) Zain (2024). To make sure the comparisons were fair, each model was trained and tested on the same IMDB 5000 Movie Dataset under the same conditions. Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and R² Score are the success measures that are calculated for each model and shown in the table below:

Table 2

|

Table 2 Comparative Evaluation with Alternate Model Baselines |

|||

|

Model |

MAE (in $M) |

RMSE (in $M) |

R² Score |

|

Random Forest |

12.46 |

18.92 |

0.879 |

|

Linear Regression |

18.73 |

25.4 |

0.722 |

|

Support Vector Regression |

21.85 |

28.67 |

0.685 |

|

Gradient Boosting |

13.62 |

20.53 |

0.853 |

In every measure, the Random Forest model did better than the others. With a R² score of 0.879, it explained the most of the variation in the data, doing much better than Linear Regression (0.722) and SVR (0.685). The MAE of $12.46 million shows that the model's predictions were off by this much on average from the real numbers. This is a lot less than the other models. Gradient Boosting also did well, with a R² of 0.853, but it wasn't as good as Random Forest, especially in MAE and RMSE. Linear Regression made more mistakes because it was more sensitive to outliers and less able to deal with relationships that weren't linear. Even though SVR can deal with non-linearity, it wasn't very accurate in this case. This was probably because the data was very complex and the income numbers weren't scaled. Using past data, Random Forest proved to be the most stable and accurate model for predicting box office income, which supported its choice for final deployment.

Figure 3

Figure 3

Model Comparison

with Different Parameter

To assess model performance under categorical prediction (e.g., classifying a movie's box office success as Low, Medium, or High), the continuous target variable (revenue) was discretized into bins. Based on the distribution, thresholds were set as Low: Revenue < $25M, Medium: $25M ≤ Revenue < $75M, High: Revenue ≥ $75M.

Models were evaluated on classification metrics after adapting them to this multiclass prediction task. The numerical performance is summarized below:

Table 3

|

Table 3 Performance Evaluation of Machine Learning Model |

||||

|

Model |

Accuracy |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-Score |

|

Random Forest |

0.87 |

0.85 |

0.84 |

0.84 |

|

Linear Regression |

0.73 |

0.68 |

0.66 |

0.67 |

|

Support Vector Regression |

0.69 |

0.64 |

0.6 |

0.62 |

|

Gradient Boosting |

0.83 |

0.81 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

The Table 3 shows how well four regression models were able to classify data in order to make specific predictions about movie success. With an accuracy of 87%, the Random Forest model was the best at classifying, which suggests that it can generalise well and handle feature variance well. Its accuracy and recall are both above 84%, which means that it consistently gets things right and makes fewer fake positives and negatives. The F1-score, which balances accuracy and memory, shows that the model works well across class lines. The Gradient Boosting Regressor came in second, with an F1-score of 0.80 and 83% accuracy, suggesting that it could be a good option. Its slightly lower recall compared to accuracy suggests that the model may value sure over coverage, which makes it good for safe forecasting situations. With 73% accuracy and an F1-score of 0.67, Linear Regression showed some classification skills, but it had trouble dealing with non-linear relationships and feature interactions that are common in movie success. Support Vector Regression also did poorly, with only 69% accuracy. This shows that it is sensitive to feature scale and might not be very good at generalising across multiple classes. Overall, the Random Forest model consistently does better in all four measures, especially its balanced F1-score of 0.84, which shows that it is strong at both continuous and categorised income forecast. This proves that it was chosen as the best machine learning model for using the IMDB 5000 Movie Dataset to predict how well a movie will do at the box office.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Model Accuracy Comparison

The Figure 4 shows how well the model predicts different types of box office results. Random Forest was the most accurate, with a score of 0.87. Gradient Boosting was next, with a score of 0.83. Linear Regression and Support Vector Regression did not work as well, showing that Random Forest was better at accurately classifying data from the IMDB 5000 dataset.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Model Precision Comparison

Each model's ability to correctly find true positives is shown by the Figure 5. With an accuracy of 0.85, Random Forest is once again in first place, closely followed by Gradient Boosting. Linear Regression and SVR are behind, which means they have a higher rate of false positives. This shows how reliable ensemble models are at making accurate predictions.

Figure 6

Figure 6 Model Recall Comparison

The Figure 6 shows recall values, which show how well models catch all the important cases. Random Forest and Gradient Boosting both have better memory, with values of 0.84 and 0.80, respectively. This shows that they are very sensitive. However, Linear Regression and SVR don't work as well because they miss more true cases, which could make it harder to find films that do well or poorly at the box office.

Figure 7

Figure 7 Model F1 Score Comparison

The F1-score line curve shows in the Figure 7, the right amount of memory and accuracy. Random Forest has the best general classification strength, as shown by its F1-score of 0.84. Gradient Boosting comes next with a 0.80, which keeps the forecasts fair. Because they don't work as well as other models, linear models aren't as good at accurately classifying box offices.

4. Conclusion

Using machine learning methods with old movie data has become a very good way to predict how well a movie will do at the box office. This study shows that data-driven models can show complex connections between many aspects of a movie, like its theme, director, cast, budget, length, and user reviews, and how well it does at the box office. Out of all the models that were looked at, Random Forest was the most accurate at both regression and classification tasks. This showed that it is strong and flexible enough to deal with the complex, nonlinear patterns that are common in entertainment datasets. The complete method, which included preparing the data, choosing the features, training the model, and evaluating its performance, showed an organised framework for accurate prediction. Key success indicators like MAE, RMSE, R² Score, Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-Score showed how well the model worked. Random Forest regularly did better than other options like Linear Regression, Support Vector Regression, and Gradient Boosting. Its constant performance across both revenue-based and classification-based factors proves that it can be used for business purposes in the film industry. Even though the results look good, there are still some problems. For example, the model doesn't take into account how audiences change over time, how marketing tactics change, or how watching platforms change. Real-time opinion analysis, social media trends, and foreign market variables should all be included in more study because of these factors. In conclusion, prediction modelling is a useful tool for makers, investors, and marketers that helps them make decisions. Stakeholders can lower financial risks and make better use of resources by using past trends and advanced machine learning models.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Bhatt, J., and Verma, S. (2020). Box Office Success Prediction Through Artificial Neural Network and Machine Learning Algorithm. In Proceedings of the First Pan IIT International Management Conference. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3753059

Cheang, Y. M., and Cheah, T. C. (2021). Predicting Movie Box-Office Success and the Main Determinants of Movie Box Office Sales in Malaysia Using Machine Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Software and Computer Applications (57–62). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3457784.3457793

Chen, S., Ni, S., Zhang, Z., and Zhang, Z. (2022). The Study of Influencing Factors of the Box Office and Prediction Based on Machine Learning Models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Robotics and Communication (1–8). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-4554-2_1

Gegres, F., Azar, D. A., Vybihal, J., and Wang, J. T. L. (2022). Early Prediction of Movie Success Using Machine Learning and Evolutionary Computation. In Proceedings of the 21st International Symposium on Communications and Information Technologies (ISCIT) (177–182). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISCIT55906.2022.9931277

Gupta, S. K., Garg, T., Raj, S., and Singh, S. (2024). Box Office Revenue Prediction using Linear Regression in Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Quantum Computation-Based Sensor Application (ICAIQSA) (1–7). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICAIQSA64000.2024.10882301

Lopes, R. B., and Viterbo, J. (2023). Applying Machine Learning Techniques to Box Office Forecasting. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Technology and Systems (189–199). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-33261-6_17

Quader, N., Gani, M. O., and Chaki, D. (2017). Performance Evaluation of Seven Machine Learning Classification Techniques for Movie Box Office Success Prediction. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Electrical Information and Communication Technology (EICT) (1–6). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/EICT.2017.8275242

San Arranz, G. (2020). Movie Success Prediction Using Machine Learning Algorithms (Unpublished manuscript).

Vardhan, S. V., Balaji, K. V. S., Kumar, C. A., and Kumar, C. J. (2025). From Buzz to Blockbuster: Predicting Movie Revenue Using a Hybrid Approach Combining Machine Learning and Sentiment Analysis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Multi-Agent Systems for Collaborative Intelligence (ICMSCI) (pp. 1220–1227). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICMSCI62561.2025.10894031

Velingkar, G., Varadarajan, R., and Lanka, S. (2022). Movie Box-Office Success Prediction Using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Power Control and Computing Technologies (ICPC2T) (1–6). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICPC2T53885.2022.9776798

Wadibhasme, R. N., Chaudhari, A. U., Khobragade, P., Mehta, H. D., Agrawal, R., and Dhule, C. (2024). Detection and Prevention of Malicious Activities in Vulnerable Network Security Using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovations and Challenges in Emerging Technologies (ICICET) (1–6). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICICET59348.2024.10616289

Zain, B. (2024). Decoding Cinematic Fortunes: A Machine Learning Approach to Predicting Film Success. In Proceedings of the 21st Learning and Technology Conference (LandT) (144–148). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/LT60077.2024.10468906

Zheng, Y., Zhen, Q., Tan, M., Hu, H., and Zhan, C. (2021). COVID-19’s Impact on the Box Office: Machine Learning and Difference-in-Difference. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Knowledge Engineering (ISKE) (458–463). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISKE54062.2021.9755401

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.