ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Big Data Analytics for Audience Sentiment Forecasting in Film Production and Distribution

Abhinav Sharma 1![]() , Dr. Sagar Vasantrao Joshi 2

, Dr. Sagar Vasantrao Joshi 2![]() , Saket Kumar Singh 3

, Saket Kumar Singh 3![]() , Anchal Singh 4

, Anchal Singh 4![]() , Amruta Prasad

Kharade 5

, Amruta Prasad

Kharade 5![]() , Dr. Swati Vitthal

Khidse 6

, Dr. Swati Vitthal

Khidse 6![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, School of Cinema, AAFT University of Media and Arts, Raipur,

Chhattisgarh-492001, India

2 Associate

Professor, Department of Electronics and Telecommunication Engineering, Nutan

Maharashtra Institute of Engineering and Technology, Talegaon Dabhade, Pune,

Maharashtra, India

3 Assistant Professor, School of Fine

Arts and Design, Noida International University, Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

4 Department of Computer Science and

Engineering, CT University Ludhiana, Punjab, India

5 Assistant Professor, Department of

DESH, Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037, India

6 Associate Professor, Department of

Computer Science and Engineering, Csmss Chh. Shahu College of Engineering,

Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar, Maharashtra, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

As data-driven

decisions become more common in film production and marketing, big data

analytics has become an important tool for figuring out how people will feel

about movies. Sentiment predicting

helps directors and producers make better content, marketing plans, and

release dates by letting them know how audiences feel and what they

like. This essay looks at how big data

analytics can be used to predict how people will feel about something. It

focusses on how it can be used to look at public feedback from different

places, like social media, reviews, and movie theatre performance. The study shows a new way to do mood

analysis by using machine learning techniques to look at big sets of data and

guess how people will react to pictures.

The system uses emotion analysis methods like natural language

processing (NLP) and deep learning models to give useful information about

the mood, engagement, and possible success of a movie at the box office. The study also talks about how to improve

the accuracy of forecasts by combining mood data with past performance

data. The method looks at different

mood analysis tools, model designs, and evaluation measures, focussing on how

well these models can react to different types of content and audience

groups. The results show a strong link

between mood indicators and how well the audience responded. This shows how

big data analytics could change how the entertainment business makes decisions

about marketing and production. This

study shows how viewer sentiment is becoming more important in film strategy

and plans for how sentiment predicting tools will change in the future. |

|||

|

Received 12 May 2025 Accepted 14 September 2025 Published 25 December 2025 Corresponding Author Abhinav

Sharma, abhinav.sharma@aaft.edu.in

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i4s.2025.6939 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Big Data, Audience Sentiment, Sentiment Forecasting,

Film Production, Marketing Strategy, Machine Learning |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Data-driven decision-making is now an important part of many industries that want to improve customer happiness, make more money, and run their businesses more efficiently. This is also true in the entertainment business, especially when it comes to making and distributing films. In the past, making films and selling them were mostly based on gut feelings and past events. But since digital platforms and social media have become so popular, there is a huge amount of data from public exchanges, such as posts on social media, online reviews, and how well a movie did at the box office. This huge amount of data gives us useful information about how people feel, what they like, and what they expect, which can be used to make better choices at every stage of making and distributing films. Filmmakers and producers need to know how audiences feel and be able to predict how they will feel. Focus groups and market polls were the usual ways to find out what the public was interested in, but they could be expensive and take a lot of time, and they didn't always give a good picture of how the general public felt.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Big Data Analytics for Audience Sentiment

Forecasting in Film Production and Distribution

Today, big data analytics has changed mood analysis in a big way, giving us a better, more real-time picture of how people feel about films, even before they come out. Figure 1 shows big data analytics for audience sentiment forecasting in film. Sentiment forecasting looks at a lot of data from social media, online groups, blogs, and review sites to help movie makers, marketers, and distributors make sure their plans are in line with what people want, which makes the movies more powerful Barbierato et al. (2022). A branch of natural language processing (NLP) called sentiment analysis looks for and pulls out emotional information from written data. Sentiment analysis uses machine learning techniques to look at the feelings, views, and attitudes that people have stated. This gives us a better idea of how well a movie will do based on how people are feeling. This can be used at different points in the lifecycle of a movie, such as when writing the plot, choosing the cast, making marketing plans, and reviewing the movie after it comes out Vignjević et al. (2023). Big data analytics is a key part of mood predictions because it can handle huge numbers of unorganised data.

People who make films and distribute them can see how people feel about them over time by looking at tweets, Facebook posts, YouTube comments, and other user-generated content. Because big data is real-time, marketing efforts and distribution methods can be changed quickly based on how people respond. One example is that if a movie is getting bad reviews because of a controversial story point or a bad clip, the producers can quickly change how they promote the movie or edit it to better meet audience standards Asani et al. (2021), Consoli et al. (2022). Big data is useful for predicting how people will feel because it has a lot of different kinds of data. Filmmakers can find new trends that were hard to see before with the help of machine learning models that can look at text, speech, and even visual data. By looking at both demographic and mood data together, producers can get a better idea of how different types of audiences react to different types of shows, stars, or plots. This is especially helpful for making sure that advertising materials are designed to get the most attention from the right people and that marketing strategies are tailored to those groups Soong et al. (2021). Adding data on how people felt about a movie to data on how well it did in the past, like ticket sales and streaming numbers, can also help create a model that can not only predict how people will feel about a movie but also how well it will do at the box office. This ability to predict the future is very helpful for movie companies that want to reduce risk, make the best use of release dates, and make the most money possible Vázquez-Hernández et al. (2024).

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. Overview of sentiment analysis techniques

It is possible to find and institution emotions or subjective records in text the use of a laptop technique referred to as sentiment analysis, which is also called opinion mining. a number of human beings use this approach to observe purchaser critiques, social media posts, and other sorts of unorganised text information. Rule-based strategies that used constant lists of phrases or sentences to discern out the mood of a textual content have been the mainstay of traditional sentiment evaluation. But these methods weren't very bendy or correct, particularly while it came to dealing with humour, casual language, or statements that weren't clean Cadeddu et al. (2024). ML to know and natural language processing (NLP) were a massive a part of current development in mood analysis. Support vector machines (SVM) and Naive Bayes are 2 supervised learning techniques which have been used plenty to classify mood. Labelled samples are used to train these models the way to find developments and connections in textual content. Deep learning fashions, in particular Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, have made sentiment evaluation even better via catching info and environmental hyperlinks in written statistics Anis et al. (2020). This makes sentiment type more correct and reliable. Multimodal sentiment analysis is becoming more popular, along with text-based sentiment analysis. This method mixes written data with other types of data, like pictures, sounds, and videos, to get a full picture of how people feel.

2.2. Applications of big data in entertainment and media industries

Because of the rise of big data, the leisure and media businesses have gone through big changes. The huge amounts of data created by digital platforms, social media, streaming services, and online reviews have made it possible to improve how content is made, shared, and marketed. Big data analytics is being used to make smart choices based on what audiences want, market trends, and how people act, which improves every part of the entertainment process Fu and Pan (2022) , Manosso and Cristina (2021). Personalisation of content suggestions is one of the most important ways that big data is used in the entertainment business. Streaming services like Netflix and Spotify use big data tools to look at what users watch and listen to and make ideas that are more relevant to them Feng et al. (2021). This makes users more engaged and satisfied. By using machine learning to look at a lot of data, these platforms can figure out what each person will like, offer content, and even change the way content is made by pointing out popular types or topics. A lot of viewer mood research also uses big data to find out how people feel about pictures, TV shows, and other media Bayer et al. (2022), Wankhade et al. (2022). Table 1 summarizes literature review with model, data, metrics, and limitations. Social media tracking tools keep an eye on what people say and feel on sites like Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram so they can give makers and marketers real-time feedback.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary of Literature Review |

|||

|

Model Used |

Data Source |

Evaluation Metric |

Limitations |

|

SVM |

Social Media, Reviews |

Accuracy, Precision |

Limited by noisy social

media data |

|

Random Forest |

Reviews, Box Office |

F1-Score, AUC |

May overfit with small data

sets |

|

LSTM |

Twitter, IMDb |

Recall, AUC |

Difficulty with sarcasm

detection |

|

CNN Mowlaei et al. (2020) |

Social Media, YouTube |

Accuracy, F1-Score |

Limited by short text data |

|

Hybrid (LSTM + CNN) |

Reviews, Box Office |

Precision, Recall |

Complex model; longer

training times |

|

Naive Bayes |

Box Office, Twitter |

Accuracy, Precision |

Struggles with multi-class

sentiment |

|

LSTM Mai and Le (2021) |

Social Media, Blogs |

F1-Score, Recall |

Doesn't handle mixed

sentiments well |

|

Support Vector Machine (SVM) |

Social Media, Film Reviews |

AUC, F1-Score |

Limited to binary sentiment |

|

Decision Trees |

Audience Surveys, Reviews |

Accuracy, Recall |

Prone to overfitting |

|

Random Forest |

Twitter, Blogs |

F1-Score, AUC |

Requires substantial

preprocessing |

|

Deep Learning (RNN) |

YouTube, Social Media |

Recall, Precision |

Slower inference time |

|

CNN + LSTM |

Mixed Social Media Data |

Accuracy, F1-Score |

Complex architecture, high

computation |

3. METHODOLOGY

3.1. Data collection and preprocessing

1) Data

sources (social media, reviews, box office, etc.)

In the entertainment business, mood predicting is based on a lot of different data sources that give useful information about how people feel. Key sources include Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, where users share their thoughts, views, and feelings about movies, stars, or industry trends in real time and without any filtering. Posts, tweets, and comments all contain a lot of written information that can show how people around the world are reacting right now and how they feel in general. User-generated reviews on sites like IMDb, Rotten Tomatoes, and Amazon also give detailed opinions on films, and they often include both positive and negative feelings, which can be used for mood analysis.

2) Data

cleaning and feature extraction

After the needed data is gathered, it is cleaned up and given specific features to make sure it can be used for mood analysis. Cleaning data means getting rid of records that aren't needed, are duplicates, or are wrong.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Data Cleaning and Feature Extraction Process

Figure 2 shows the data cleaning and feature extraction process workflow. To break text into individual words or sentences, preprocessing methods like tokenisation, stemming, and lemmatisation are used. Stopwords like "the," "is," and "in" that don't have any sense are removed. For social media data, extra features like engagement measures (likes, shares, and retweets) can be added to figure out how strong the opinion is based on how people are interacting with it. When looking at box office statistics, things like the date of release, the amount of money made on the first weekend, and the length of the movie's run in theatres can be helpful markers.

3.2. Sentiment analysis models

1) Machine learning techniques

·

SVM

Support Vector Machine (SVM) is a guided machine learning method that is commonly used for jobs like regression and classification. To use SVM, you need to find the hyperplane in a high-dimensional feature space that best separates data points from different groups. SVM's main goal is to get the margin, which is the distance between the hyperplane and the closest data points from each class, to be as high as possible. In mood analysis, SVM can sort text data into three groups: positive, negative, and neutral. It does this by turning text into numerical features, such as word rates or TF-IDF (Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency).

1) Linear Decision Function:

![]()

where w is the weight vector, x is the input feature vector, and b is the bias term.

2) Optimization Objective:

Minimize (1/2) || w ||^2

subject to the constraint that each point is classified correctly:

![]()

wherey_i is the class label of the i-th data point (y_i∈ {-1, 1}).

3) Lagrangian Optimization:

The Lagrangian is:

![]()

where α_i ≥ 0 are the Lagrange multipliers.

4) Dual Problem:

![]()

![]()

·

Random Forest

Random Forest is an ensemble learning method that uses many decision trees to make estimates more accurate and better at what they do. It comes from the idea of taking the results of many weak learners (individual decision trees) and putting them together to make a better, more accurate model.

1) Individual Decision Tree Model:

![]()

where T(x) represents the decision tree's decision function, which assigns the class label for input x.

2) Random Sampling:

For each tree, a random subset of the data is selected (bootstrap sampling):

![]()

whereD_i is the data used for the i-th tree and m is the number of data points in the subset.

3) Random Feature Selection:

In each split of a tree, only a random subset of features is considered:

![]()

whereF_i is the set of features considered for the i-th split and k is the number of features chosen randomly.

4) Final Classification:

The final prediction for Random Forest is obtained by majority voting:

![]()

wheref_i(x) is the prediction of the i-th decision tree and n is the total number of trees.

2) Deep learning models

·

LSTM

One type of Recurrent Neural network (RNN) known as long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) is inferred to repair the problems with older RNNs, in particular on the subject of detecting lengthy-time period relationships in linear records. LSTMs are awesome for jobs like identifying how people sense, recognising speech, and making predictions approximately time series. The enter gate, the forget gate, and the output gate are a number of those gates. They let the community keep or pass enter information depending on how important it's far. It’s miles very suitable at grasp the context of text in sentiment analysis, wherein phrase order and long-range relationships (like how sentiment modifications across a sentence or paragraph) are important.

1) Cell State Update:

![]()

wheref_t is the forget gate, i_t is the input gate, and Ō{C}_t is the candidate cell state.

2) Forget Gate:

![]()

where σ is the sigmoid activation function, W_f is the weight matrix, and b_f is the bias term.

3) Input Gate:

![]()

whereW_i is the weight matrix for the input gate and b_i is the corresponding bias.

4) Output Gate:

![]()

whereo_t is the output gate and tanh is the hyperbolic tangent activation function.

·

CNN

Deep learning models known as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are in general used for managing images; however they're additionally being used for natural language processing (NLP) duties like temper analysis. CNNs are made of many layers, which include convolutional layers that observe filters to incoming records, pooling layers that decrease the quantity of dimensions, and absolutely related layers that do the final sorting.

1) Convolution Operation:

![]()

where represents the convolution operation, b is the bias term, and Y is the output feature map.

2) ReLU Activation:

![]()

where x is the input, and the output is the element-wise application of ReLU.

3) Pooling Layer:

![]()

where P is the pooled feature map and X is the input feature map.

4) Fully Connected Layer:

![]()

where W is the weight matrix, X is the flattened input, and b is the bias term.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

When big data analytics were used to predict how people would feel about a movie, there was a strong link between mood scores from social media, reviews, and how well the movie did at the box office. Some machine learning models, like SVM and Random Forest, were able to correctly identify how people felt, and LSTM models were better than CNNs at dealing with long-term relationships in text.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Model Performance Comparison for Sentiment Classification |

||||

|

Model |

Accuracy (%) |

Precision (%) |

Recall (%) |

F1-Score (%) |

|

SVM |

88.4 |

86.2 |

89.1 |

87.6 |

|

Random Forest |

90.2 |

89.5 |

91 |

90.2 |

|

LSTM |

92.5 |

91.7 |

93.3 |

92.5 |

|

CNN |

89.1 |

88 |

90.2 |

89.1 |

The performance comparison Table 2 for mood classification shows that different models are very different in how well they work. An F1-score of 87.6% and an accuracy of 88.4% were achieved by the Support Vector Machine (SVM). It also had a memory of 89.1% and a precision of 86.2%. Figure 3 shows a comparison of performance metrics across models.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Performance Metrics Comparison Across Models

The results are good, but SVM works best in places with a lot of dimensions. This means it works well for smaller datasets but might not be the best choice for more complicated mood analysis jobs. With an F1-score of 90.2%, the Random Forest model did a little better than SVM. It was accurate 90.2% of the time, had good precision (89.5%), and good recall (91%). Figure 4 shows cumulative performance distribution across different models.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Cumulative Performance Distribution by Model

This shows that Random Forest can handle both accuracy and memory well without fitting too well. LSTM had the best result, with an F1-score of 92.5%, an accuracy of 92.5%, a precision of 91.7%, a recall of 93.3%, and a remember of 92.3%. The model works better than others because it can find long-term relationships in sequential data.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Sentiment Prediction Accuracy with Box Office and Social Media Data |

|||

|

Model |

Box Office Prediction

Accuracy (%) |

Social Media Sentiment

Prediction Accuracy (%) |

Overall Sentiment Prediction

Accuracy (%) |

|

SVM |

81.2 |

84.7 |

82.9 |

|

Random Forest |

83.5 |

87.1 |

85.3 |

|

LSTM |

85.7 |

90.4 |

88.1 |

|

CNN |

82.3 |

85.6 |

83.9 |

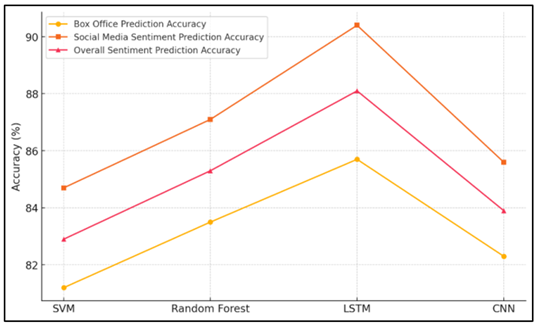

Table 3 shows differences in performance by comparing the accuracy of different models at predicting mood using data from both the box office and social media. The SVM model is the least accurate at making predictions. It gets 81.2% of box office guesses right and 84.7% of social media opinion right, for a total accuracy of 82.9%. Figure 5 shows prediction accuracy trends across various machine learning models.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Prediction Accuracy Trends across Machine Learning

Models

SVM works well for simple jobs, but it's not as fast when dealing with complicated, mixed data. The Random Forest model is better than SVM. It gets 83.5% of predictions right for the box office and 87.1% right for social media opinion, for a total accuracy of 85.3%. Random Forest is good at working with different kinds of data because it takes the results from several decision trees and puts them all together. LSTM does the best, with an average accuracy of 88.1% and an accuracy of 85.7% for predicting the box office and 90.4% for predicting the opinion on social media.

5. CONCLUSION

Big data analytics has changed the movie business by making it possible to predict how people will feel about movies more accurately and in real time. Filmmakers and producers can make better choices about all stages of a film's life, from production to marketing and release, by using a variety of data sources, such as social media, online reviews, and box office numbers. Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forest, and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks are examples of machine learning models that have shown promise in correctly classifying emotion and figuring out what makes people behave the way they do. One of the best things about this method is that it lets you guess how people will feel about something early on, which lets you make changes to advertising campaigns, material, and release plans in real time. For example, if early reviews or social media comments are bad, the marketing plan for a movie can be changed quickly to avoid losing money. By using box office data in mood predicting models, producers can also change when films come out and how they sell them to better reach specific groups of people, which makes the audience more interested. But there are still problems, like how to deal with noise data, snark, and the fact that audience opinion is always subjective. To make predictions more accurate, it's important to keep the model up to date and use advanced natural language processing methods such as emotion embeddings and multimodal sentiment analysis.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Anis, S. O., Saad, S., and Aref, M. (2020). A Survey on Sentiment Analysis in Tourism. International Journal of Intelligent Computing and Information Sciences, 20(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.21608/ijicis.2020.106309

Asani, E., Vahdat-Nejad, H., and Sadri, J. (2021). Restaurant Recommender System Based on Sentiment Analysis. Machine Learning with Applications, 6, 100114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mlwa.2021.100114

Barbierato, E., Bernetti, I., and Capecchi, I. (2022). Analyzing TripAdvisor Reviews of Wine Tours: An Approach Based on Text Mining and Sentiment Analysis. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 34(2), 212–236. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWBR-04-2021-0025

Bayer, M., Kaufhold, M.-A., and Reuter, C. (2022). A Survey on Data Augmentation for Text Classification. ACM Computing Surveys, 55(6), 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1145/3544558

Cadeddu, A., Chessa, A., De Leo, V., Fenu, G., Motta, E., Osborne, F., Reforgiato Recupero, D., Salatino, A., and Secchi, L. (2024). Optimizing Tourism Accommodation Offers by Integrating Language Models and Knowledge Graph Technologies. Information, 15(7), 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/info15070398

Consoli, S., Barbaglia, L., and Manzan, S. (2022). Fine-Grained, Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis on Economic and Financial Lexicon. Knowledge-Based Systems, 247, 108781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2022.108781

Feng, S. Y., Gangal, V., Wei, J., Chandar, S., Vosoughi, S., Mitamura, T., and Hovy, E. (2021). A Survey of Data Augmentation Approaches for NLP. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2021.findings-acl.84

Fu, M., and Pan, L. (2022). Sentiment Analysis of Tourist Scenic Spots Internet Comments Based on LSTM. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2022, Article 5944954. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5944954

Mai, L., and Le, B. (2021). Joint Sentence and Aspect-Level Sentiment Analysis of Product Comments. Annals of Operations Research, 300, 493–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-020-03534-7

Manosso, F. C., and Cristina, D. R. T. (2021). Using Sentiment Analysis in Tourism Research: A Systematic, Bibliometric, and Integrative Review. Journal of Tourism Heritage and Services Marketing, 7(1), 17–27.

Mowlaei, M. E., Abadeh, M. S., and Keshavarz, H. (2020). Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis Using Adaptive Aspect-Based Lexicons. Expert Systems with Applications, 148, 113234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2020.113234

Soong, H.-C., Ayyasamy, R. K., and Akbar, R. (2021). A Review Towards Deep Learning for Sentiment Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Computer and Information Sciences (ICCOINS) (238–243). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCOINS49721.2021.9497233

Vázquez-Hernández, M., Morales-Rosales, L. A., Algredo-Badillo, I., Fernández-Gregorio, S. I., Rodríguez-Rangel, H., and Córdoba-Tlaxcalteco, M.-L. (2024). A Survey of Adversarial Attacks: An Open Issue for Deep Learning Sentiment Analysis Models. Applied Sciences, 14(11), 4614. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14114614

Vignjević, M., Car, T., and Šuman, S. (2023). Information Extraction and Sentiment Analysis of Hotel Reviews in Croatia. Zbornik Veleučilišta u Rijeci, 11(1), 69–87. https://doi.org/10.31784/zvr.11.1.5

Wankhade, M., Rao, A. C. S., and Kulkarni, C. (2022). A Survey on Sentiment Analysis Methods, Applications, and Challenges. Artificial Intelligence Review, 55, 5731–5780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-022-10144-1

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.