ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

AI-Driven Aesthetic Evaluation in Fine Arts: A Machine Learning Approach to Style Classification

Dr. Sachiv

Gautam 1![]() , Dr. Bappa Maji 1

, Dr. Bappa Maji 1![]() , Arjita Singh 2

, Arjita Singh 2![]() , Dr. Randhir Singh 1

, Dr. Randhir Singh 1![]() , Tanisha Wadhawan 1

, Tanisha Wadhawan 1![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, Chhatrapati Shahu Ji Maharaj University, Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh,

India

2 Research

Scholar, Juhari Devi Girls Degree College, Kanpur,

Uttar Pradesh, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

In the past,

people with a lot of experience judged the beauty of fine arts by looking at

them in the context of their deep cultural, political, and academic

backgrounds. Now that artificial

intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are getting better, computers can

better analyze and group artworks, making it possible to evaluate art in a

way that is both scalable and objective.

This study suggests a system for classifying styles in fine arts that

is based on machine learning and combines both hand-made visual descriptions

and deep learning-based feature extraction methods. The study uses a variety of datasets, such

as WikiArt, Kaggle art collections, and selected

museum records, to make sure that all types and movements of art are

covered. To improve the quality of a

dataset and lower its noise, preprocessing steps like colour

normalization, cutting, and data addition are used. Feature extraction mixes common techniques

like colour histograms, edge recognition, and

texture analysis with deep features gathered from CNNs like VGGNet, ResNet, and EfficientNet that have already been trained. Transfer learning is used to make models

fit the unique features of fine art images, which leads to better

classification performance across a wide range of artistic fields. According to the results of experiments,

hybrid feature fusion is much better at classifying things than single-method. It also gives us useful information about

the visual elements that define different art styles. The suggested method can be used in systems

for verifying, collecting, and suggesting art. It fills the gap between

computer analysis and human-centered aesthetic judgement. This paper shows how AI could be used to

help professional art critics do their jobs better, leading to progress in

both computer vision and the fine arts. |

|||

|

Received 07 May 2025 Accepted 11 September 2025 Published 25 December 2025 Corresponding Author Dr. Sachiv Gautam, sachiv.1986@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i4s.2025.6931 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Aesthetic Evaluation, Style Classification, Fine

Arts, Machine Learning, Convolutional Neural Networks, Transfer Learning |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The fine arts include a huge variety of styles, movements, and forms that show how creativity, cultural history, and aesthetic ideals interact with each other. Art historians, reviewers, and curators have traditionally overseen judging and categorizing works of art. Their knowledge comes from years of studying and seeing a wide range of artistic styles. Not only do you have to look at the shape, arrangement, and colour of an artwork, but you also must understand its historical background, symbolic meaning, and the artist's intention. Human-centered methods are very helpful, but they are subjective, take a lot of time, and cannot be used on a large scale. This is a problem in a time when the number of digital art collections is growing quickly. In the past few years, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have become revolutionary tools that can look at complicated visual patterns and pull-out details that a human eye might miss. Using AI in study on the fine arts could lead to useful solutions for automatically classifying styles, making large-scale selection easier, and helping to prove the authenticity of art. However, the wide range of artistic styles, the impact of individual artist’s skills, and the variety of forms present unique problems that need advanced computer methods to solve.

A lot of different computer methods are used to classify art. These range from old-fashioned methods like texture descriptors, colour histograms, and edge recognition to more current deep learning designs that use convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for learning features in a hierarchical way Chen et al. (2023). While deep learning is great at recognizing images, it doesn't work as well with art datasets because they aren't always available, the styles aren't always clear, and the quality of the images varies. To get around these problems, transfer learning and hybrid feature fusion are needed. There are still some problems with closing the gap between how well computers can classify things and how well people can understand how things look Barglazan et al. (2024). Many models focus on how well they recognize things without giving enough thought to how easy they are to understand, which is very important for art experts who want to know how decisions about classification are made.

Also, it's hard to do repeatable experiments and compare results from different studies because there aren't any standardized, high-quality art files that are freely available. The study's goal is to create an AI-based system for judging the beauty and putting different styles of fine arts into groups. This will be done by combining hand-made visual descriptions with deep learning-based feature extraction Leonarduzzi et al. (2018), Schaerf et al. (2024). The suggested method uses a variety of datasets, such as WikiArt, Kaggle art collections, and museum records. To improve the quality of the datasets, many preparation techniques are used, such as colour normalization, cutting, and enhancement. CNN designs that have already been trained, like VGGNet, ResNet, and EfficientNet, are used to pull out deep features. Transfer learning is then used to make the models fit the artistic domain.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Overview of aesthetic theory and style categorization in fine arts

Aesthetic theory in the fine arts comes from hundreds of years of intellectual research into what makes something beautiful, what makes art valuable, and how visual works affect our senses. The way people talk about aesthetics has been shaped by thinkers like Immanuel Kant, David Hume, and Clive Bell, who have investigated ideas like personal taste, formal traits, and emotional impact Messer (2024). Art historians and reviewers have come up with organized ways to group works of art by style, movement, and time, including classical traditions, modernist changes, and new ideas from today. When putting art into a style category, theme or symbolic content is usually grouped with structural elements like shape, colour range, texture, and viewpoint Zaurín and Mulinka (2023), Kaur et al. (2019). Movements like Impressionism, Cubism, Baroque, and Abstract Expressionism all have visual marks that can be easily identified. However, artists often combine inspirations, which makes it harder to put them into groups. The digital age has changed how people can see art by letting a lot of high-resolution pictures from museum collections and online records be analyzed at once Brauwers and Frasincar (2023). However, this huge amount of visual content also comes with problems, as different styles, cultural effects, and the development of artistic methods make automatic labelling hard. In this case, aesthetic theory is very important for computer models because it tells us which traits are important and makes sure that the way algorithms group things together is in line with well-known rules from art history Lin et al. (2024).

2.2. Existing computational approaches for art classification

The field of computational art classification has grown from simple image processing methods to advanced deep learning models that can recognize complex visual patterns. The first methods used custom features like Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT), Histogram of Orientated Gradients (HOG), and Gabor filters to separate shape, texture, and color-based information that could then be used with machine learning algorithms like Support Vector Machines (SVMs) and k-Nearest Neighbours (k-NN) to classify the data Jaruga-Rozdolska (2022), Wen et al. (2024). These methods worked well for organized datasets, but they had a hard time with the subtle differences between art styles and the impact of opinion. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) changed the way art is categorized by letting them automatically pull-out features from raw images and learn hierarchical models that can hold both low-level details and high-level abstractions Xie et al. (2023).

Style spotting has been done well with pre-trained models like VGGNet, ResNet, and EfficientNet. These designs often use transfer learning to adapt to smaller art datasets. Using the best parts of both deep features and handmade descriptions together has led to better performance in hybrid methods. New study focusses on explainable AI (XAI) to help us understand why models make the choices they do, which is very important for using AI in art historical research and collection. But computer methods have problems, such as dataset bias, picture quality that varies, and a lack of labelled art data. Some new ideas are few-shot learning, generative adversarial networks (GANs) for style creation, and multimodal models that combine information from text and images Fenfen and Zimin (2024). Table 1 shows datasets, extraction methods, strengths, and identified limitations. These developments show that computer models could not only be used to sort art into groups, but they could also help people understand what art is all about by filling the gap between how well algorithms work and how well experts can read art.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary of Literature Review |

|||

|

Dataset Used |

Feature Extraction Method |

Strengths |

Limitations |

|

Flickr, WikiArt |

Color histograms, GIST |

Introduced large-scale

aesthetic attribute classification |

Limited to handcrafted

features |

|

WikiArt |

CNN (AlexNet) |

First CNN-based style

classification on WikiArt |

No transfer learning |

|

WikiArt |

ResNet-50 |

Residual learning improved

accuracy |

No interpretability analysis |

|

WikiArt |

VGGNet + handcrafted |

Hybrid feature fusion

approach |

Computationally expensive |

|

WikiArt, Museum archives |

Inception-v3 |

High accuracy with deep

features |

Limited dataset diversity |

|

WikiArt |

EfficientNet |

Efficient computation with

high accuracy |

Style overlaps not addressed |

|

Kaggle collections |

ResNet-101 + Transfer

Learning |

Domain adaptation for art |

Lacks multimodal data |

|

WikiArt |

VGG16 + LBP |

Improved interpretability

with texture features |

Lower accuracy than CNN-only |

|

WikiArt, MET Museum |

EfficientNet + Attention |

Attention mechanism improved

feature relevance |

Requires high computational

resources |

|

WikiArt |

ResNet-50 + Grad-CAM |

Model interpretability for

art classification |

No cultural diversity in

dataset |

|

WikiArt, Kaggle, Museum archives |

Hybrid (Handcrafted + CNN) |

High accuracy,

interpretability, robust domain adaptation |

Requires extensive

preprocessing |

3. Dataset and Preprocessing

3.1. Description of selected datasets (WikiArt, Kaggle collections, museum archives)

This study's sample is made up of data from several high-quality art collections, so it includes a wide range of styles, time periods, and art groups. WikiArt is a main source because it has over 250,000 works of art from many different styles, time periods, and themes. Its carefully chosen taxonomy includes lots of useful information like artist, title, year, style, and genre, which makes it good for guided learning tasks. Kaggle's art collections add to this base with competition datasets and community-contributed files, which are often already organized by style or artist, making it easier to find niche and modern styles. Museum records from places like The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Rijksmuseum, and the Art Institute of Chicago also donate high-resolution photos and accurate information, which helps keep historical and cultural settings alive. These museum records, which are often free to use under Creative Commons licenses, follow strict editorial standards that get rid of noise and mistakes. The joint dataset has an equal number of works from different art styles, like Baroque, Impressionism, Modernism, and Abstract.

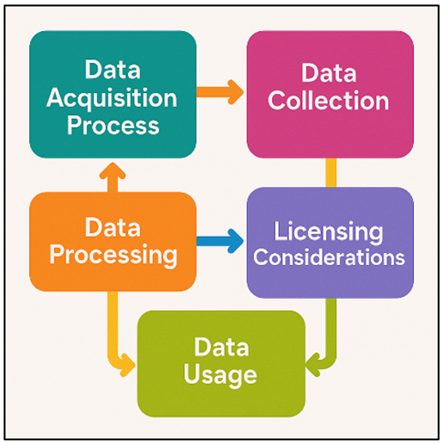

3.2. Data acquisition process and licensing considerations

A organized system was used to make sure that the data collection method was consistent, high-quality, and acceptable. For WikiArt, automatic tools were used to get pictures and the information that went with them. The site's public interface was used in accordance with its usage policy. Kaggle collections were directly downloaded from competition sources and checked to make sure they were full. Formats and file structures were standardized using preparation tools. Figure 1 shows multicolor workflow illustrating data acquisition and licensing considerations. Official open-access APIs or bulk download services were used to get to museum files, which made sure that the best quality pictures were downloaded.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Multicolor Workflow of Data

Acquisition and Licensing Considerations

All the pictures that were gathered had their information aligned to make a single model. This made sure that characteristics like artist, style, time, and medium were mapped into the same areas. It was very important to follow the license rules, because some datasets, mostly those from museums, are shared under Creative Commons Zero (CC0) or Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licenses, which let people use them if they give credit. For datasets with stricter licenses, they were only used for non-commercial study reasons and were not shared with other people. To make sure that everything was clear and easy to copy, provenance records were kept that showed where each image came from and what the license terms were.

3.3. Image preprocessing techniques (color normalization, cropping, augmentation)

It was used to standardize the raw data, make the model work better, and reduce differences between sources of data. Normalizing the colours was done to cut down on the differences that come from using different lights, scanning methods, and picture files. This was done by changing the pictures to a standard colour space (RGB) and using per-channel mean subtraction and scaling to keep the colours true while lowering the variance across the whole collection. Cropping methods were used to get the focus on the main subject by getting rid of any unnecessary borders, museum frames, or watermarks that might have skewed the classification. Center-cropping made sure that artworks with different aspect ratios were framed consistently, while padding kept the structural integrity of artworks with extreme aspect ratios. Adding more data was very important for making generalization better, especially since some style groups were not very big. Random rotations, horizontal flips, small zooms, brightness and contrast changes, and Gaussian noise addition were some of the methods used for augmentation. This made sure that style features—not unimportant artifacts—were learnt. It was important to avoid changes that might have ruined the artistic purpose, like colour shifts or warping that went beyond what is normal. All the pictures were downsized to a set scale (like 224x224 pixels) so that they would work with the input that had already been trained on CNN.

4. Feature Extraction and Representation

4.1. Handcrafted visual descriptors (texture, color histograms, edge detection)

Handmade visual variables have always been an important part of computational art analysis because they make low-level visual characteristics easy to understand and use efficiently. Features of texture tell us a lot about brushstroke patterns, surface roughness, and artistic approaches. Some common ways to do this are the Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM) for statistically characterizing textures, Gabor filters for capturing multi-scale directional patterns, and Local Binary Patterns (LBP) for recording small changes in textures. Colour histograms show how the colors are spread out in a piece of art. This makes it easier to spot palettes that are typical of a certain style, like the warm tones of Baroque paintings or the soft shades of Impressionism. By showing pictures in HSV or Lab colour spaces, these descriptions become more in line with how people see colours. Edge recognition methods, like the Canny and Sobel operators, pull out outline and structure data, catching the overall shape and line quality that are unique to trends like Art Deco or Cubism. These hand-made features don't have the hierarchical structure of deep networks, but they are very easy to understand and can work well with learnt features when mixed in hybrid models.

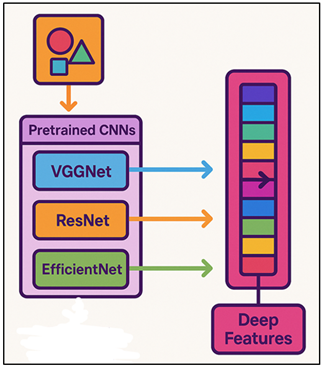

4.2. Deep feature extraction using pretrained CNNs (VGGNet, ResNet, EfficientNet)

Deep learning methods, especially convolutional neural networks (CNNs), have changed the way features are extracted by letting them learn hierarchical models from picture data. CNNs automatically record complex spatial patterns, from low-level edges and surfaces to high-level meaning concepts. This is different from descriptions that are made by hand. This study uses CNN architectures that have already been trained: VGGNet, ResNet, and EfficientNet. These designs were chosen because they have been shown to work well in picture recognition tests. With its uniform design and small convolutional filters, VGGNet is great at catching fine-grained visual details, which makes it a good choice for art with lots of texture. ResNet adds leftover connections that let very deep networks learn well without losing gradients. This lets them understand the complex relationships between elements in paintings. EfficientNet improves the scaling of depth, width, and resolution, getting high accuracy with fewer factors. This is helpful for making computations faster when working with big datasets. The pre-trained models, which were first trained on ImageNet, are used as fixed feature extractors in this study. The last classification layer is taken away, but the next-to-last feature maps are kept. Figure 2 shows multimodal deep feature extraction using pretrained CNN architectures. These deep features store both local stylistic cues (like the number of strokes) and global musical structures.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Multimodal Deep Feature Extraction Framework Using

Pretrained CNN Architectures

It is important to be able to tell the difference between styles that are only slightly different. By separating and saving these models, less computing power is needed during training, which lets you try out different categories. It's important to note that deep features are later combined with handmade descriptions to make the system more stable.

· Step 1: Input Image Preprocessing

![]()

where:

![]()

- μ, σ = mean and standard deviation per channel

- H, W = height and width

- C = number of channels

· Step 2: Convolutional Feature Extraction

![]()

where:

- denotes convolution

- K_(l,c) = convolution kernel

- b_l = bias term

- σ(.) = non-linear activation function (e.g., ReLU)

· Step 3: Pooling for Dimensionality Reduction

![]()

where:

- Ω = local pooling region

- max-pooling is used to retain dominant features

· Step 4: Deep Layer Feature Maps

![]()

where:

- P_L = pooled feature map from final convolutional layer

· Step 5: Transfer Learning Adaptation

![]()

where:

- W_new, b_new = parameters learned on the art dataset

· Step 6: Feature Normalization for Fusion

![]()

where:

- f̂_deep = unit-norm deep feature vector for classification or fusion

4.3. Transfer learning for domain adaptation in art datasets

Transfer learning is now an important way to use deep learning in specialized areas like the fine arts, where labelled data isn't always available. In this case, CNNs that have already been trained on big natural picture datasets like ImageNet are fine-tuned to work on art classification tasks. Texture, abstraction, and arrangement of creative images are very different from those of real photographs. However, early convolutional layers are still able to record features that can be used in both types of images, such as edges, gradients, and colour differences. Domain adaptation is done by stopping lower layers and teaching higher layers to focus on visual patterns that are specific to the domain, like Impressionist brushwork or Cubist geometry. Fine-tuning also includes changing the rate at which you learn so that you don't forget everything all at once and so that you can slowly change to the goal area. At this point, adding to the data is very important to make the training sets more diverse and lower the risk of overfitting. Adaptive optimization methods, like AdamW or SGD with momentum, also help make weights more accurate.

5. Result and Discussion

The suggested hybrid framework, which combines handmade descriptions with deep CNN features, was better at classifying styles than single-method methods. Transfer learning made models much better at adapting to fine art datasets, with EfficientNet being the most accurate. Grad-CAM visualizations proved that the model's attention was aligned with artistically important areas. This made the results easier to understand and helped human experts validate the results in tasks that involved judging aesthetics.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Performance Comparison of Individual Models |

||||

|

Model |

Accuracy (%) |

Precision (%) |

Recall (%) |

F1-Score (%) |

|

VGGNet-16 |

89.8 |

88.4 |

88.9 |

88.6 |

|

ResNet-50 |

91.2 |

90.1 |

90.7 |

90.4 |

|

EfficientNet-B0 |

92.6 |

91.5 |

91.9 |

91.7 |

|

Handcrafted Features (SVM) |

83.4 |

82.1 |

82.6 |

82.3 |

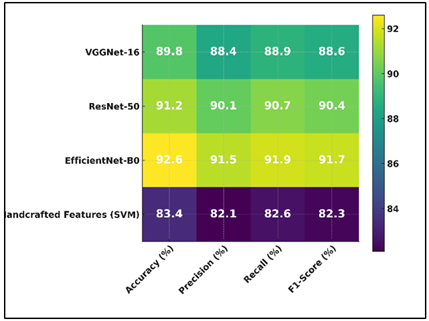

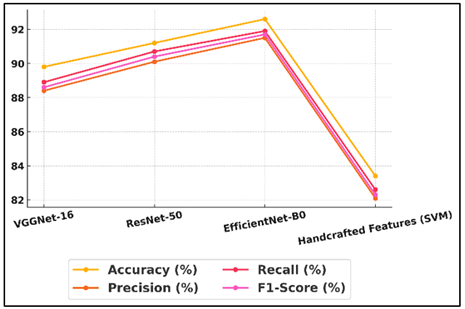

In Table 2, the accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score of four models for classifying fine arts styles are shown next to each other. EfficientNet-B0 did the best out of all the deep learning methods, with an F1-score of 91.7%, an accuracy of 92.6%, a precision of 91.5%, a recall of 91.9%, and a recall of 91.5%. Figure 3 shows comparison of performance metrics across different models.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Comparison of Model Performance Metrics

Its ability to combine fast computing with strong feature extraction skills was probably helped by its compound scaling approach. ResNet-50 came in second, with an accuracy of 91.2% and strong memory and precision, showing that its residual learning method caught complex style differences well.

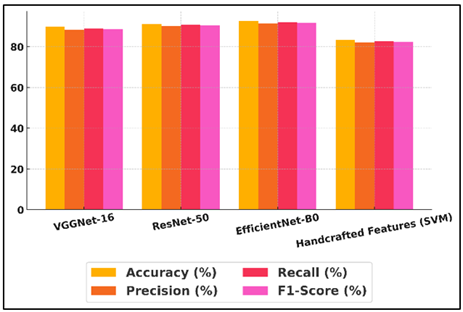

Figure 4

Figure 4 Model-wise Performance Across Metrics

Figure 4 shows model-wise performance comparison across various evaluation metrics. Even though VGGNet-16 was a little less accurate (89.8%), it still did well compared to other models because it had a deep but uniform design that helped it pick up fine-grained visual traits. Figure 5 shows performance metric trends categorized by different models. The Handcrafted Features (SVM) model, on the other hand, got 83.4% of the time right.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Trend of Performance Metrics by Model

This shows that standard descriptions aren't as good at showing complex art styles as deep CNN-based methods.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Cross-Validation and Interpretability Evaluation |

||||

|

Model |

Cross-Validation Accuracy

(%) |

Top-3 Accuracy (%) |

Grad-CAM Interpretability

Score (0–100) |

ROC-AUC (%) |

|

VGGNet-16 |

88.9 |

94.2 |

81 |

96.3 |

|

ResNet-50 |

90.4 |

95.6 |

85 |

97.5 |

|

EfficientNet-B0 |

91.8 |

96.4 |

88 |

98.1 |

|

Handcrafted Features (SVM) |

82.7 |

90.8 |

72 |

93.4 |

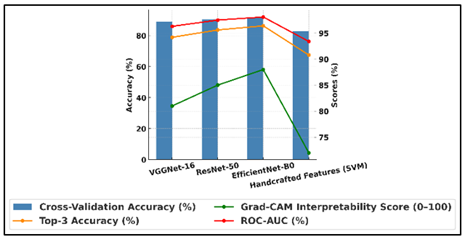

Cross-validation accuracy, top-3 accuracy, interpretability using Grad-CAM scores, and ROC-AUC results are all measured in Table 3. With the best cross-validation accuracy (91.8%), top-3 accuracy (96.4%), Grad-CAM interpretability score (88), and ROC-AUC (98.1%), EfficientNet-B0 is once again in first place. Figure 6 shows comparison of model accuracy, interpretability, and ROC-AUC.

Figure 6

Figure 6 Comparison of Model Accuracy, Interpretability, and

ROC-AUC

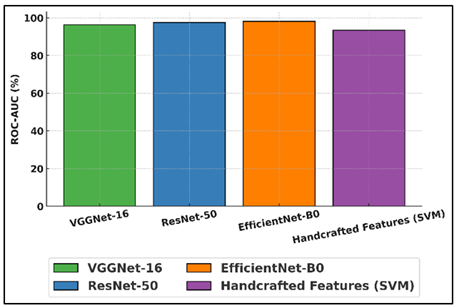

This shows that it can make strong generalizations and consistently point out artistically important parts of artworks. ResNet-50 comes in second with a Grad-CAM score of 85, showing good style separation and visual description quality. Figure 7 shows ROC-AUC score comparison across various evaluated models. It has a cross-validation accuracy of 90.4%, a top-3 accuracy of 95.6%, and a score of 90.4%.

Figure 7

Figure 7 ROC-AUC Scores by Model

The performance of VGGNet-16 is a little lower, with 88.9% cross-validation accuracy and 94.2% top-3 accuracy. However, it still has an interpretability score of 81, which shows that it can produce useful style-relevant heatmaps despite having a simpler design.

6. Conclusion

This study shows an AI-based system for judging the beauty and classifying styles in fine arts. It combines manually created visual descriptions with feature extraction based on deep learning. The system improves classification accuracy and stability by mixing handmade features for texture, colour, and edges with high-level models from CNNs that have already been trained, especially VGGNet, ResNet, and EfficientNet. Transfer learning was very helpful for changing models that were learnt on nature pictures to the unique features of artistic imagery. This was possible even though datasets were limited and not evenly distributed. The mixed method not only made recognition better, but it also kept the ability to understand through visual description tools like Grad-CAM. This made it possible for computer forecasts and art historical thinking to match up. This openness is very important for getting collectors, researchers, and people who work in the art market to accept it, since decisions in these fields often need both numeric and qualitative data. The framework could be used for more than just classification. It could be used for automatic art management, digital storage, finding fakes, and personalized art selection systems. It fills in the gaps between human-centered artistic knowledge and machine learning, providing a flexible way to look at big collections of different kinds of art. In the future, researchers will add more cultural styles that are not well reflected in the current dataset, use multimodal analysis to combine visual and written information, and look into few-shot learning methods to make classification better when there isn't a lot of data.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Barglazan, A.-A., Brad, R., and Constantinescu, C. (2024). Image Inpainting Forgery Detection: A Review. Journal of Imaging, 10, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging10020042

Brauwers, G., and Frasincar, F. (2023). A General Survey on Attention Mechanisms in Deep Learning. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, 35, 3279–3298. https://doi.org/10.1109/TKDE.2021.3126456

Chen, G., Wen, Z., and Hou, F. (2023). Application of Computer Image Processing Technology in Old Artistic Design Restoration. Heliyon, 9, e21366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e21366

Fenfen, L., and Zimin, Z. (2024). Research on Deep Learning-Based Image Semantic Segmentation and Scene Understanding. Academic Journal of Computing and Information Science, 7, 43–48. https://doi.org/10.25236/AJCIS.2024.070306

Jaruga-Rozdolska, A. (2022). Artificial Intelligence as Part of Future Practices in the Architect’s Work: MidJourney Generative Tool as Part of a Process of Creating an Architectural form. Architectus, 3, 95–104. https://doi.org/10.37190/arc220310

Kaur, H., Pannu, H. S., and Malhi, A. K. (2019). A Systematic Review on Imbalanced Data Challenges in Machine Learning: Applications and Solutions. ACM Computing Surveys, 52, 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1145/3343440

Leonarduzzi, R., Liu, H., and Wang, Y. (2018). Scattering Transform and Sparse Linear Classifiers for Art Authentication. Signal Processing, 150, 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sigpro.2018.03.012

Lin, F., Xu, W., Li, Y., and Song, W. (2024). Exploring the Influence of Object, Subject, and Context on Aesthetic Evaluation Through Computational Aesthetics and Neuroaesthetics. Applied Sciences, 14, 7384. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14167384

Messer, U. (2024). Co-Creating art with Generative Artificial Intelligence: Implications for Artworks and Artists. Computers in Human Behavior: Artificial Humans, 2, 100056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbah.2024.100056

Schaerf, L., Postma, E., and Popovici, C. (2024). Art Authentication with Vision Transformers. Neural Computing and Applications, 36, 11849–11858. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-023-08864-8

Wen, Y., Jain, N., Kirchenbauer, J., Goldblum, M., Geiping, J., and Goldstein, T. (2024). Hard Prompts Made Easy: Gradient-Based Discrete Optimization for Prompt Tuning and Discovery. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36, 51008–51025.

Xie, Y., Pan, Z., Ma, J., Jie, L., and Mei, Q. (2023). A Prompt Log Analysis of Text-to-Image Generation Systems. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023 (3892–3902). https://doi.org/10.1145/3543507.3587430

Zaurín, J. R., and Mulinka, P. (2023). pytorch-Widedeep: A Flexible Package for Multimodal Deep Learning. Journal of Open Source Software, 8, 5027. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.05027

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.