ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

AI-Assisted Post-Processing in Creative Photography

Vivek Saraswat 1![]()

![]() ,

Bhaskar Mitra 2

,

Bhaskar Mitra 2![]()

![]() , Dr. Omprakash Das 3

, Dr. Omprakash Das 3![]()

![]() , Udaya Ramakrishnan 4

, Udaya Ramakrishnan 4![]()

![]() , Abhijeet Panigra 5

, Abhijeet Panigra 5![]() , Pranali Chavan 6

, Pranali Chavan 6![]()

1 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

2 Assistant

Professor, Department of Fashion Design, Parul Institute of Design, Parul

University, Vadodara, Gujarat, India

3 Assistant Professor, Department of

Centre for Internet of Things, Siksha 'O' Anusandhan (Deemed to be University),

Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

4 Assistant Professor, Department of

Computer Science and Engineering, Aarupadai Veedu Institute of Technology,

Vinayaka Mission’s Research Foundation (DU), Tamil Nadu, India

5 Assistant Professor, School of

Business Management, Noida International University, Greater Noida, Uttar

Pradesh, India

6 Department of Computer Engineering, Vishwakarma

Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037 India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

AI-assisted

post-processing has become a revolutionary paradigm in creative photography

and changed the way photographers augment, interpret, and convey visual

stories. Older post-processing processes are based on extensive use of manual

manipulation and pre-processing filters that do not necessarily require

technical skills and can require significant amounts of time to execute and

are less flexible to the creative intentions of individuals. Recent

developments in artificial intelligence, especially in machine learning and

deep learning, permit smart and context-dependent post-processing systems

that contribute to human creativity but will not substitute it. The paper

describes the concept of AI-assisted post-processing as a co-creative model

where photographers and intelligent models are engaged in refining images

together and enhancing them by refining sharpness, color, tonal arrangement,

and artistic processing. The study outlines a conceptual paradigm of human-AI

interaction, automation degree, and preservation of a creative intent to make

sure that AI interventions are still intelligible and aligned with the

artistic vision. The AI methods are discussed, such as neural denoising,

super-resolution, HDR reconstruction, neural color grading, and style transfer

models with the focus on photographic aesthetics. The article talks about a

modular system design, with preparation of datasets, feature extraction in

the domains of color, texture, lighting and composition, and the training and

inference pipelines, which will be useful to deploy in practice. Evaluation

techniques combine both quantitative metrics of image quality and qualitative

aesthetic metrics and user studies of photographers and visual artists. The

results point to the fact that AI-assisted post-processing can make the work

much more efficient, consistent, and creatively explored, and at the same

time, preserve author control. |

|||

|

Received 07 June 2025 Accepted 21 September 2025 Published 28 December 2025 Corresponding Author Vivek

Saraswat, vivek.saraswat.orp@chitkara.edu.in

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i5s.2025.6914 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: AI-Assisted Photography, Post-Processing, Deep

Learning, Human–AI Co-Creativity, Image Enhancement, Creative Workflows |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

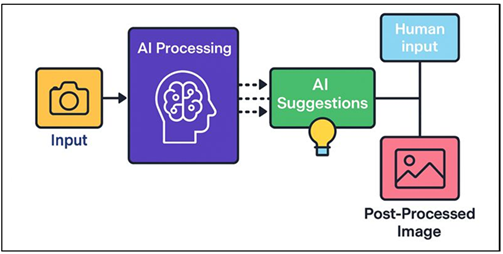

Creative photography has never been a matter of the technical or artistic where post processing is an important component to convert the scenes captured to interesting visual stories. Since the first days of darkroom methods like dodging, burning, and chemical toning, up through the current digital processes, like applications like Photoshop and Lightroom, post-processing has developed as a necessary continuation of the photographic purpose. Nevertheless, conventional digital post-processing is highly manual, tool-based, and relies on user judgment, and is usually time-consuming and repetitive in terms of its effects on obtaining consistent aesthetic results across large sets of images. Such limitations increase when photographic practices are broadened to include the work of fine art, fashion, documentary, advertising, and social media, which all require different visual imagery and quick turnaround Ploennigs and Berger (2023). Recent developments in artificial intelligence have brought new opportunities of redefining photographic post-processing as an adaptive, intelligent and a collaborative creative experience. At semantic and perceptual scales, machine learning and deep learning models can be used to comprehend the visual content, and thus, images can be automatically enhanced and restored and transformed in style. They include convolutional neural networks, generative adversarial networks, transformer-based vision models that can be trained to give complex mappings between low-quality and high-quality images, low and high-resolution images, or neutral and stylized color casts Hanafy (2023). Instead of using uniform filters, AI systems are capable of changing processing decisions with regard to the context of the scene, the nature of the light, the features of the subject, and the composition. In Figure 1, human-AI co-creative architecture allows intelligent post-processing of photographs. The post-processing with the help of AI changes the human creative process, which is characterized as a strictly manual paradigm, to a hybrid human-AI one.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Human–AI Co-Creative Framework for Intelligent

Photographic Post-Processing

In this type, the photographers define their creative objectives (mood, color emotion, stylistic references) and AI systems make intelligent recommendations, previews and refinements. Notably, AI tools do not disrupt human authorship, they operate as creative companions that enhance artistic intent and allow experimentation with a wide range of aesthetic potential through the use of limited effort Phillips et al. (2024). The other characteristic feature of the AI-assisted post-processing is its ability to be consistent and scalable. Functioning of professional photographers and studios often handles large collections of images, in which it is difficult to ensure that color grading, tonal balance and style consistency remain consistent. Based on a trained AI model on curated collections of photographs, it is possible to learn desirable aesthetic patterns and use them across image batches, enhancing workflow efficiency without quality reduction Maksoud et al. (2022). Meanwhile, adaptive learning will enable models to change as the photographer changes their style with time, enabling individual creative identities.

2. Related Work and Literature Review

2.1. Traditional digital image enhancement techniques

Classical methods of digital image enhancement are the basis of the modern photographic post-processing processes. These algorithms are mostly rule-based, and their implementation is based on signal processing, colour scientific and heuristic adaptation to enhance image quality and appeal. The typical operations are contrast stretching, histogram equalization, gamma correction, sharpening, denoising, white balance correction and tone mapping. Photoshop, lightroom, and Gimp are software programs that include sliders and curves, through which photographers can adjust the exposure, highlights, shadows, saturation and color balance in manually Müezzinoğlu et al. (2023). Although these tools provide a high level of fine-control, their performance is very much reliant on the expertise of the user and his or her aesthetic judgment. Bilateral filtering, frequency-domain enhancement and unsharp masking are advanced methods which have been extensively used to enhance clarity of edges as well as noise reduction without loss of detail. High Dynamic Range (HDR) imaging techniques combine several exposures to capture the detail in shadows and highlights, but if the tone mapping is not done properly then the result may be unnatural Jaruga-Rozdolska (2023). Although the traditional approaches are strong and interpretable, they are generalized to all images and do not recognize the semantic meaning of the scenes. This makes them difficult to deal with changes of complex lighting conditions, mixed color casts, and context sensitive enhancement. These restrictions have stimulated the formulation of data-driven methods that can learn adaptive and content-aware post-processing methods Paananen et al. (2023).

2.2. Machine Learning Approaches in Photographic Editing

Machine learning changed the paradigm in photographic editing by allowing the models to legally gain knowledge of how to improve photographs based on data as opposed to having handcrafted rules. Regression models, decision trees, and support vector machines were the first machine learning models used to predict optimal exposure, white balance, or color correction using the features extracted in the image. The low-level descriptors that were usually employed in these systems included color histograms, texture statistics, and gradient features to transform input images into superior outputs Tong et al. (2023). The learning based on examples was especially influential, and in this case, models were trained to learn the transformation between paired datasets of original and professionally edited photos. The transfer of tonal and color features of reference images to new input was done using techniques like k-nearest neighbors and random forests. Intelligent photo organization, automatic cropping, and evaluation of aesthetic quality were other machine learning techniques that assisted in editorial decision-making Maksoud et al. (2023). The ML-based methods were more flexible and customized than the traditional methods and, thus, the systems could estimate the editing style of an individual. Nevertheless, their results were limited by a small number of representations of features and the use of descriptors which have been engineered by humans. Cross scene and cross lighting generalization were also difficult, and the performance was not fine textured fidelity Zhang et al. (2023).

2.3. Deep Learning Models for Style, Color, and Texture Manipulation

With the capability to learn high-level, hierarchical visual representations, deep learning models have been given a central focus in sophisticated photographic post-processing. The convolutional neural nets (CNNs) facilitate end-to-end training of the complex mappings in denoising, super- prison, color correction, and tone improvement learning. The use of generative adversarial networks (GANs) enhanced further the realism as the networks have been trained to produce visually realistic textures and style features which became useful in artistic rendering and restoration applications Maksoud et al. (2020). The methods of neural style transfer can utilize correlations among features in a neural network to decouple and reintegrate content and style to allow photographers to use painterly or cinematic effects without damaging the structure of the image. Transformer-based vision models and diffusion models have lately shown better control over global color harmony, lighting effects and finer grained texture generation Maksoud et al. (2022). Learned color grading is also supported by deep learning where the models are asked to provide the emotional tone and mood of reference images or textual cues. As opposed to previous approaches, deep models are able to use semantic knowledge, separating the subject and the background and applying the edits to them. In spite of their strength, they have issues associated with data dependency, cost of computation, and explainability. Table 1 is a summary of AI-assisted post-processing in creative photography. Black-box behaviour has the disadvantage of masking creative explanation, and there is research being done into interpretable and controllable deep models.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary of Related Work on AI-Assisted Post-Processing in Creative Photography |

||||

|

Technique |

Application Domain |

Advantages |

Benefits |

Impact and Future Trends |

|

Classical Color Transfer |

Color Grading |

Simple, interpretable |

Consistent color mapping |

Basis for learning-based

grading |

|

Edge-Aware Filters Maksoud et al. (2023) |

Image Enhancement |

Fast processing |

Improved sharpness |

Inspired hybrid AI–filter models |

|

ML Regression Model |

Photo Enhancement |

Style learning |

Personalized edits |

Precursor to deep models |

|

Example-Based ML |

Exposure Correction |

Adaptive enhancement |

Automated exposure |

Shift toward data-driven editing |

|

CNN (SRCNN) |

Super-Resolution |

High detail recovery |

Image clarity |

Foundation for GAN SR models |

|

Neural Style Transfer Rozema et al. (2022) |

Artistic Rendering |

Artistic flexibility |

Creative exploration |

Spawned modern style tools |

|

GAN (SRGAN) |

Super-Resolution |

Photorealistic textures |

Print-quality outputs |

GAN-based restoration trend |

|

CNN-Based Photo Enhancement |

Mobile Photography |

End-device learning |

Professional look |

Mobile AI photography growth |

|

Deep HDR Networks Brendlin et al. (2022) |

HDR Imaging |

Natural tone mapping |

Balanced exposure |

Real-time HDR evolution |

|

Learning-to-See-in-the-Dark |

Low-Light Enhancement |

Extreme noise handling |

Night photography |

Computational photography boom |

|

Attention-Based CNN |

Color Grading |

Skin-tone protection |

Cinematic grading |

Semantic-aware editing |

|

Transformer Vision Models |

Global Tone Control |

Consistent aesthetics |

Scene-level harmony |

Transformer adoption |

|

Diffusion Models Nam et al. (2021) |

Restoration and Style |

High realism |

Fine artistic control |

Diffusion-based editing |

|

Personalized AI Editors |

Adaptive Post-Processing |

Style individuality |

Creative identity support |

Human-centered creative AI |

3. Conceptual Framework of AI-Assisted Post-Processing

3.1. Human–AI co-creative interaction model

The model of human-AI co-creative interaction places artificial intelligence as a co-creative partner, and not a passive automation tool in the post-processing of photographs. Within the context, the photographer would be the ultimate author, determining the creative objective, like mood, narrative focus, color feeling, and references to style, and the AI system would give smart suggestions, adaptive changes, and real-time visual feedback. Communication is done within cycles of interaction as human will dictates algorithmic recommendations and model results drive additional creative decisions. User interfaces are very important because they convert a complex model operation into understandable controls like semantic sliders of warmth, drama, softness or cinematic tone. The AI uses acquired depictions of light, composition, and beauty to suggest context-sensitive advances to eliminate technical heavy lifting and broaden creative investigation. Notably, the co-creative model facilitates testing, which allows the quick creation of various editing variations, which encourages photographers to contrast, optimize, and crossbreed styles. The system can learn individual preferences over time by use of feedback mechanisms such as user acceptance, rejection or manual refinement of AI suggestions.

3.2. Levels of Automation: Assistive, Collaborative, and Autonomous Editing

Post-processing, which is assisted by AI, can be designed in three different levels of automation, providing various levels of creative control and algorithmic freedom. Assistive editing is the least advanced, with AI serving as an engine of suggestions, making changes to exposure, contrast, color balance and/or noise reduction. Photographers maintain all final decision making powers with choices being selective or altering proposed edits. The collaborative editing will bring a more profound collaboration between AI systems, which are actively involved in the editing process by implementing initial improvements, creating stylistic variants, and dynamically reacting to user feedback. Workflows on this level turn iterative and human involvement directs the process of refinement, as well as AI hastens repetitive or technically complex processes. Autonomous editing is the ultimate form of automation where AI-based systems automatically process the images according to the pre-defined aesthetic profiles or acquired preferences. These come in handy especially in large volume situations such as event photography, journalism or content creation in social media where speed and consistency are of the essence. But independent editing impacts the issues of creative homogenization and lacking authorial nuance.

3.3. Creative Intent Preservation and Interpretability

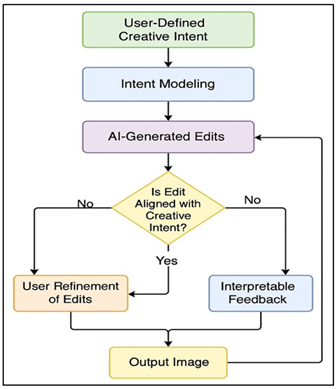

Maintaining the intent of the creative process is one of the essential needs of AI-assisted post-processing systems, so that enabling an algorithmic intervention must not ruin but add value to the artistic intent of the photographer. Subjective items included under creative intent are mood, emotional connection, narrative focus and stylistic identity, which are immeasurable, and nonetheless vital to photographic expression. AI models should thus include mechanisms to accommodate user-specified goals and constraints e.g. reference images, style descriptors or configurable semantic parameters. To ensure this alignment, interpretability is essential because it allows the user to understand the decisions made by AI. Visual attention maps, layer-wise relevance visualization, and before and after comparisons are techniques that can make a photographer understand what and why certain edits are made. The diagram below (Figure 2) demonstrates that in the editing process with AI assistance, workflow preserves creative intent and interpretability. Explainable interfaces enable the user to follow the evolution of color, texture or lighting to model reasoning which builds trust and conscious control. Also, the reversible editing pipelines and non-destructive workflows are necessary so that the creative decisions become flexible and recoverable.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Flowchart for Creative Intent Preservation and Interpretability

in AI-Assisted Photographic Editing

The originality and authenticity can be supported by AI-assisted systems using intent-aware modeling and interpretable feedback to utilize the computational intelligence. This is the balance needed to be ethically and creatively acceptable on the use of AI tools in photography, and this strengthens the role of the photographer as the ultimate authority in creativity.

4. AI Techniques for Post-Processing

4.1. Image enhancement and restoration models (denoising, super-resolution, HDR)

Image restoration and image enhancement form fundamental uses of AI in post-processing of photographs, and deal with sensor noise, low-resolution, and difficult lighting. Some AI based denoising models are constructed using convolutional neural networks, residual learning frameworks and there are more denied the ability to remove noise and distortions and fine textures and edges by the equivalent filters which tend to smooth edges and details excessively. Super-resolution restores high-frequency data to low-resolution images with the help of deep networks, which results in sharper images that can be printed at high-resolution formats, or users can zoom in and out with digital images. Generative adversarial networks also increase the perceptual realism by creating realistic textures that match statistics of natural images. The High Dynamic Range (HDR) reconstruction models are a combination of several exposures or an inference of the missing luminance data of single images that generate balanced outputs with better shadows and highlight. An AI-based approach is able to reduce ghosting effects and preserving natural color grading as opposed to the classical HDR pipeline. The models of enhancements are commonly trained on the paired data of degraded and high-quality images, which enables end-to-end optimization. The fact that they are integrated into post processing processes saves on time of manual corrections and enhances the quality of the baseline images prior to creative editing processes.

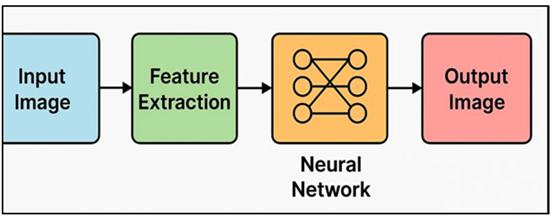

4.2. Color Grading and Tonal Adjustment Using Neural Networks

Grade and tonality are important in the development of mood, emotion, and visual unity in photography. Neural network-based methods allow it to perform transformations of colors based on data and not just on the presets and lookup tables. Deep learning models can be trained on high-quality reference images graded by a professional color grader, with high-resolution, deep color mappings of the input image, utilizing small details of correlation between luminance and chroma as well as context of scene. The convolutional networks are able to make predictions of per-pixel or region-specific changes, which permits differentiated treatment of the sky, skin color, and backgrounds.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Neural Network–Based Color Grading and Tonal

Adjustment Pipeline for Creative Photography

ransformer-based and recurrent architectures also enable tonal consistency globally all over the sequences of images and are useful in series based projects and cinematic workflows. The neural network pipeline of color grading and tonal adjustments is represented in Figure 3. High-level descriptors (warmth, contrast, vibrancy or cinematic tone, etc.) can also be integrated into the neural color grading system, converting the abstract creative intent into specific color processes. The models are faster, more repeatable, and have stylistic consistency as compared to manual grading yet have user intervention.

4.3. Style Transfer and Artistic Rendering Techniques

The methods of style transfer and artistic rendering allow applying AI-assisted post-processing not only to the enhancement but also to the expressive transformation. The neural style transfer is a type of model that uses the content structure and style components like the brush strokes, coloration, and pattern styles that deep networks have trained on, and transfers them over a different texture. Through the combination of these representations, photographers are able to use artistic styles based on paintings, films, or illustrative aesthetic and retain necessary scene geometry. Generative adversarial networks enhance the realism of style, by applying the constraint of perceptual consistency, and minimizing the artifacts of the early methods of style transfer. Diffusion-based models also support more control by making it possible to refine the stylistic characteristics gradually and iteratively, allowing users to control between realism and abstraction. Illustrative effects and sketch generation as well as painterly abstraction are also developed using artistic rendering models and are not limited to regular photography. Notably, the system of the modern era focuses on controllability by means of adjustable style strength, reference specific use and area specific use. These functionalities help to express the subtle artistry instead of the single-button makeovers. Although the stylistic AI tools bring up the issue of novelty and aesthetic homogenization, co-creative workflows help to increase the risks since the photographer can choose styles and optimize them, enabling him to take control. Due to this, style transfer methods are creative amplifiers, which allow photographers to experiment with various visual languages while not losing authorship and intent.

5. System Architecture and Implementation

5.1. Data acquisition and photographic dataset preparation

Effective AI-assisted post-processing systems are based on data acquisition and dataset preparation. Photographic datasets should be of high quality and diverse to facilitate the strength of the datasets in terms of variety of genres, lighting and style records. Sources of data usually encompass professional collections of photos, online repository curated collections, collections of data provided by camera producers and archives provided by photographers themselves. The images are taken in various groups like portraits, landscape, street photography, low-light photography, and artistic images to embrace large aesthetic diversity. Normalization of resolution, color space standardization and the elimination of corrupted or low quality samples are some of the preprocessing steps. In case of supervised learning jobs, professional-edited versions of the original images are created in pairs and paired datasets are used to train the model, which learns how to improve original images and make them better or more stylish. Training data is also enhanced with metadata (i.e. camera settings, exposure value, lens information, and shooting conditions) that give the necessary context. There is enhancement of generalization and robustness by applying data augmentation techniques, such as geometric transformations, color jittering, noise injection, and exposure variation.

5.2. Feature Extraction: Color Spaces, Textures, Lighting, and Composition

The ability of AI models to process and manipulate photographic content through feature extraction helps them in interpreting photographic data and encoding visual qualities into meaningful data. It uses various color spaces including RGB color space, HSV color space, LAB color space, and YCbCr color space that describe the complementary aspects of chromatic and luminance color space. Surface patterns, gradient statistics or deep feature maps produced by convolutional networks are represented by texture features as spatial filters or gradient statistics, respectively. Lighting features are used to represent the distribution of illumination, contrast ratios, shadow and highlight relationship, and dynamic range which are used in exposure correction and HDR reconstruction. Features of composition The context-sensitive adjustments that composition-aware features achieve include studying spatial layout, centrality of subject, depth information and saliencies, and respects photographic compositional principles, like the rule of thirds and visual balance. Deep neural networks are becoming progressively popular in modern systems to learn hierarchical features representations using only the data, avoiding the use of handcrafted descriptors. Explicit feature modeling however is useful in terms of interpretability and user control. The low and high-level features enable AI systems to become semantically aware of the content of a scene, enabling them to treat subjects and backgrounds in different ways. Effective feature extraction guarantees that the post-processing decisions made have esthetic consistency in addition to artistic intent, and constitutes an important bridge between uncoded raw image data and intelligent editing operations.

5.3. Model Training, Fine-Tuning, and Inference Pipeline

Model training and inference pipeline determines the way AI-assisted post-processing systems learn, evolve, and work in real-life processes. Training is usually performed by starting with pre-trained deep models that are initialized with the large-scale image datasets in order to learn some general visual representations. Such models are then optimized on domain-specific photographic datasets to be trained to learn to enhance, color grade or perform some stylistic changes. To trade between fidelity and aesthetics, loss functions are based upon pixel-level reconstruction terms as well as perceptual, adversarial and style-consistency losses. Fine-tuning; It can be used to adapt to a particular genre or the preferences of individual photographers with smaller curated datasets and optimize them using feedback. Inference Inference involves a series of modular steps that the images go through; preprocessing, feature extraction, model execution, and post-edit rendering. The problem of real-time is solved with compressing, quantization of the models, and using hardware acceleration in the GPUs or edge devices. Man-free editing processes save AI-generated edits as parameter layers, which allows refinement to be done manually and repeatedly. The mechanisms of continuous learning can use the user feedback to change the model behavior as time progresses. An intelligent pipeline has to be designed to be scaleable, responsive, creatively flexible, and the application of AI to post processing becomes feasible and user-friendly in the studio setting of professional photography.

6. Evaluation Methodology

6.1. Quantitative metrics: PSNR, SSIM, color fidelity, and sharpness indices

Quantitative assessment gives a definite base of the technical effectiveness of post-processing systems with the help of AI. The reconstruction quality and, in particular, the quality of images in denoising, super-resolution, and restoration is commonly quantified by the Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) by comparing pixel-wise differences between the output image and some reference standards. To complement PSNR, Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM) measures perceptual similarity taking into consideration luminance, contrast and structural information, which are much more relevant to human visual perception. The metrics play a vital role in comparison of the color grading models particularly when it comes to the aspects of maintaining skin tone and mood stability. Indexes that are sharpness indices measure how clearly edges are defined and how well the details are preserved, either using gradient-based metrics or analyzing using the frequency domain to identify whether sharpening is over doing it or it is an artifact of sharpening. Collectively these measures allow the comparison between AI-assisted products and baseline practices to be done in a systematic way. Nevertheless, quantitative measures cannot possibly be used to fully express aesthetic quality because they possibly can promote similarity of pixels instead of creative interpretation. Thus, the metrics can be regarded as auxiliary tools of technical strength, stability and visual integrity, ensuring that AI-enhanced improvements do not affect image quality or assist in creative processes.

6.2. Qualitative Assessment: Aesthetic Quality and Creative Expressiveness

To measure the artistic contribution of the AI-assisted post-processing, the qualitative assessment is critical, focusing on the aspects that cannot be measured in terms of numerical values. The aesthetic quality is usually judged by the review of experts, as photographers, visual artists, and design experts evaluate products in terms of the composition balance, color harmony, the depth of the tones, and the emotional appeal. The expressiveness of creativity is explored in measuring the effectiveness with which the image of the processed image is presented to express mood, narrative intent, and style identity. Comparative studies provide original images with AI-enhanced and manually edited ones, which can be evaluated by the evaluator in terms of authenticity, originality, and visual attractiveness. Subjective perceptions are represented by rating scales and pair wise comparisons, as well as by open ended feedback. The qualitative assessment is also based on the ability of AI interventions to enrich or weaken the voice of a photographer, especially related to its use in art and documentary work. Another important requirement is visual consistency among sets of images, particularly when the project should be stylistically consistent. Although these are subjective, these measures offer valuable critical information on the real-life creative acceptance. Through incorporating qualitative analysis alongside technical metrics, evaluation frameworks will guarantee that AI-aided post-processing can assist creativity as well as artistic excellence and that the performance of the systems is aligned with the expectation of the creative professionals.

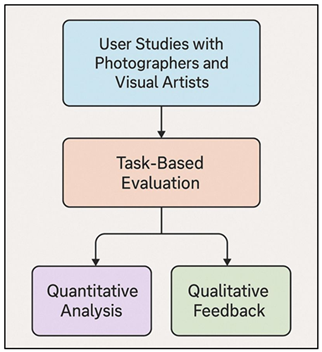

6.3. User Studies with Photographers and Visual Artists

The usability, effectiveness, and creative impact of post-processing systems with AI help will be highly evaluated through user studies. Various types of photographers and visual artists, both professionals and amateurs, are asked to use AI tools in controlled or real-world editing exercises, such as those related to photography and video. They will usually be requested to carry out post-processing tasks with the help of both conventional and AI-based systems, which allows to compare efficiency and satisfaction levels with the results of creative tasks. Measurements gathered are the time to complete a task, number of times a task had to be manually changed and perceived workload, and subjective ones, including trust, perceived control, and empowerment of creativity.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Flowchart of User Study Design for Evaluating AI-Assisted

Photographic Post-Processing

User experiences and preferences are recorded with the help of surveys, interviews, and observational studies, which will help to understand how AI affects creative decision-making. In Figure 4, the user study workflow is evaluated through the effectiveness of AI-assisted photographic post-processing. User studies also evaluate learning curves and adaptability, in specific, learning and making efficient use of AI features, how quickly a user can learn how to use it. These studies provide feedback that is used to refine the system, interface design and personalization. Notably, user-centered assessment would make sure that AI-aided post-processing would correspond to the actual creative activities and is not defined by strictly technical standards. User studies confirm the usefulness and aesthetic feasibility of AI-based solutions of photographic post-processing by basing system evaluation on human experience.

7. Challenges and Future Research Directions

7.1. Generalization across diverse photographic styles

Among the most prominent problems with AI-assisted post-processing are the realization of strong generalization in a variety of photographic styles, genres, and cultural aesthetics. The photographic practice takes divergent forms, in light, color philosophy, norms of composition, or intent to expressiveness, and includes minimalistic documentary approaches to highly refined forms of fine art and commercial photography. The models developed using the limited or biased data might be overfitted to the patterns that are mostly prevalent and, thus, produce homogenized results, without regard to the diversity between styles. The differences in camera sensors, lenses, and shooting conditions also make things more complex on generalization as models should change to fit various noise types, respond differently to colors, and dynamic range. To resolve this issue, big, equal, and culturally adaptable data sets are needed, in addition to domain adaptive learning methods. Adaptability to unseen styles can be enhanced using technologies like multi-domain training, style-conditioned modeling and meta-learning. Systems that are aligned to particular aesthetic intentions can also be used by including references given by the photographer and interactive feedback. The next way to prevent aesthetic bias in research is to focus on cross-cultural analysis and design with an eye to fairness. Using generalization to enhance the processing systems can enable the AI assisted post-processing systems to serve a wider range of creative expression without dictating the same visual standards to all.

7.2. Real-Time and Edge-Based AI Post-Processing

Edge-based and real-time AI after-processing is a key boundary to intelligent editing being incorporated into cameras, mobiles and in the field of work. Despite the high quality results, deep learning models have a tendency to be computationally expensive, which means that they cannot be deployed in real-time, especially on resource limited systems. The need to be able to optimize models to achieve low-latency performance is met by different model optimization methods, including pruning, quantization, knowledge distillation, and lightweight architecture design. Compared to using cloud infrastructure, edge-based processing is more privacy-enhancing, more reliable, and more responsive in professional and consumer applications. Real-time AI post-processing provides users with a visual feedback as soon as the capture is made, and photographers can make changes to the creative decision onsite. Nonetheless, it is quite difficult to strike a balance between the performance and the visual appearance, and the aggressive compression may compromise the quality of textures and colour precision.

8. Conclusion

Artificially intelligent post-processing is an important development in creative photography, changing the intersection of technical improvement in the creative process and expression in the workflow of the modern world of art. Photography is drifting away from paradigms of rigid and manual adjustments to smart and intelligent systems that operate through machine learning and deep learning by installing machine learning and deep learning systems in post-processing pipelines. Instead of substituting human-made creativity, AI is an empowering co-worker, which simplifies technical processes, speeds up the workflow, and increases the area of aesthetic play. In this paper, the theoretical framework, technical architectures, and testing schemes underlying the AI-assisted post-processing have been discussed. Since the neural color grading and style transfer methods are no less than the improvement and restoration models, AI has high potential to enhance the quality of images as well as facilitate the expressive visual storytelling. The suggested architectures focus on human-AI cooperation, progressive automation, and preservation of creative intent, which are important issues to control, interpretability, and authenticity. Quantitative indicators and qualitative evaluations combined point to the fact that AI systems of success need to be technologically faithful yet aesthetically and emotionally evocative. Meanwhile, such issues as generalization across different styles, constraints of real-time deployment, and personalization are still researched areas.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Brendlin, A. S., Plajer, D., Chaika, M., Wrazidlo, R., Estler, A., Tsiflikas, I., Artzner, C. P., Afat, S., and Bongers, M. N. (2022). AI Denoising Significantly Improves Image Quality in Whole-Body Low-Dose Computed Tomography Staging. Diagnostics, 12, 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12010225

Hanafy, N. O. (2023). Artificial Intelligence’s Effects on Design Process Creativity: A Study on Used A.I. Text-To-Image in Architecture. Journal of Building Engineering, 80, 107999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107999

Jaruga-Rozdolska, A. (2023). Artificial Intelligence as Part of Future Practices in the Architect’s Work: MidJourney Generative Tool as Part of a Process of Creating an Architectural form. Architectus, 3, 95–104. https://doi.org/10.37190/arc220310

Maksoud, A., Al-Beer, B., Hussien, A., Dirar, S., Mushtaha, E., and Yahia, M. (2023). Computational Design for Futuristic Environmentally Adaptive Building forms and Structures. Architectural Engineering, 8, 13–24. https://doi.org/10.23968/2500-0055-2023-8-1-13-24

Maksoud, A., Al-Beer, H. B., Mushtaha, E., and Yahia, M. W. (2022). Self-Learning Buildings: Integrating Artificial Intelligence to Create a Building That can Adapt to Future Challenges. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 1019, 012047. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1019/1/012047

Maksoud, A., Hussien, A., Mushtaha, E., and Alawneh, S. (2023). Computational Design and Virtual Reality Tools as an Effective Approach for Designing Optimization, Enhancement, and Validation of Islamic Parametric Elevation. Buildings, 13, 1204. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13051204

Maksoud, A., Mushtaha, E., Chouman, L., Al Jawad, E., Samra, S. A., Sukkar, A., and Yahia, M. W. (2022). Study on Daylighting Performance in the CFAD Studios at the University of Sharjah. Civil Engineering and Architecture, 10, 2134–2143. https://doi.org/10.13189/cea.2022.100532

Maksoud, A., Sahall, H., Massarweh, M., Taher, D., Al Nahlawi, M., Maher, L., Al Khaled, S., and Auday, A. (2020). Parametric-nature obsession. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology, 29, 2091–2095.

Müezzinoğlu, M. K., Akan, S., Dilek, H. Y., and Güçlü, Y. (2023). An Analysis of Spatial Designs Produced Through Midjourney in Relation to Creativity Standards. Journal of Design, Resilience, Architecture and Planning, 4, 286–299. https://doi.org/10.47818/DRArch.2023.v4i3098

Nam, J. G., Ahn, C., Choi, H., Hong, W., Park, J., Kim, J. H., and Goo, J. M. (2021). Image Quality of Ultralow-Dose Chest CT Using Deep Learning Techniques: Potential Superiority of Vendor-Agnostic Post-Processing Over Vendor-Specific Techniques. European Radiology, 31, 5139–5147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-020-07537-7

Paananen, V., Oppenlaender, J., and Visuri, A. (2023). Using Text-To-Image Generation for Architectural Design Ideation. International Journal of Architectural Computing, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/14780771231222783

Phillips, C., Jiao, J., and Clubb, E. (2024). Testing the Capability of AI Art Tools for Urban Design. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCG.2024.3356169

Ploennigs, J., and Berger, M. (2023). AI Art in Architecture. AI in Civil Engineering, 2, Article 8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43503-023-00018-y

Rozema, R., Kruitbosch, H. T., van Minnen, B., Dorgelo, B., Kraeima, J., and van Ooijen, P. M. A. (2022). Structural Similarity Analysis of Midfacial Fractures: A Feasibility Study. Quantitative Imaging in Medicine and Surgery, 12, 1571–1578. https://doi.org/10.21037/qims-21-564

Tong, H., Türel, A., Şenkal, H., Yagci Ergun, S. F., Güzelci, O. Z., and Alaçam, S. (2023). Can AI Function as a New Mode of Sketching. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 18, 234–248. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v18i18.42603

Zhang, Z., Fort, J. M., and Giménez Mateu, L. (2023). Exploring the Potential of Artificial Intelligence as a Tool for Architectural Design: A Perception Study Using Gaudí’s Works. Buildings, 13, 1863. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13071863

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.