ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

cReinforcement Learning in Musical Improvisation

Thara P 1![]()

![]() ,

Tarang Bhatnagar 2

,

Tarang Bhatnagar 2![]()

![]() , Indira Priyadarsani Pradhan 3

, Indira Priyadarsani Pradhan 3![]() , Dr. Jairam Poudwal 4

, Dr. Jairam Poudwal 4![]()

![]() , Dr. Dhamodaran S 5

, Dr. Dhamodaran S 5![]()

![]() , Shailesh Kulkarni 6

, Shailesh Kulkarni 6![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Aarupadai Veedu

Institute of Technology, Vinayaka Mission’s Research Foundation (DU), Tamil

Nadu, India

2 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

3 Assistant Professor, School of

Business Management, Noida International University, Greater Noida, Uttar

Pradesh, India

4 Assistant Professor, Department of

Fine Art, Parul Institute of Fine Arts, Parul University, Vadodara, Gujarat,

India

5 Associate Professor, Department of

Computer Science and Engineering, Sathyabama Institute of Science and

Technology, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

6 Department of E and TC Engineering, Vishwakarma

Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037 India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

As a synthesis

of real-time choices, awareness of style and expressiveness, musical

improvisation is a complicated creative process. Implementing a conventional

generative music system that uses supervised learning will tend to favor the

approach that is only adaptive and exploratory of the approach used in

improvisational performance. The paper explores how reinforcement learning

(RL) can be applied to musical improvisation and presents the task as a

sequence decision-making problem where an intelligent agent is trained to

produce musically coherent and musical sequences by being exposed to an

evaluative environment. The structure of music is represented as a Markov

decision process with the states representing melodic intervals, harmonic

context and rhythmic patterns, and actions representing the choice of notes,

continuity of phrases and strategies of ornamentation. One of the main works

offered by this work is the design of multi-objective reward functions which

balance tonal and temporal coherence, stylistic and creative novelty. The

offered framework of RL-based improvisation is a combination of feature

extraction, a learning agent, evaluative feedback modules, and a symbolic

output generator. The training is performed with datasets based on professional

improvisation recording, with auxiliary rule-based musical constraints,

aesthetical feedback by the listener in addition to model based evaluators.

Q-learning, Deep Q-Networks, Proximal Policy Optimization and hybrid RL-deep

learning models are used to make comparative experiments. |

|||

|

Received 06 June 2025 Accepted 20 September 2025 Published 28 December 2025 Corresponding Author Thara P, tharaselvi1985@gmail.com

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i5s.2025.6911 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Reinforcement Learning, Musical Improvisation,

Generative Music, Reward Design, Sequential Decision-Making, Creative AI |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Few human creativity types are as refined as musical improvisation, where the choice is made on the spot without prior thought, where the style is well informed, and where time and harmony limits are constantly challenged. In contrast to composition, where a composition can be refined with repetitions, improvisation is dynamic and the performer must reconcile between anticipations of the music and improvisation. Improvisers are constantly aware of the context of the music, are able to anticipate future progression and they choose what they want to do which still creates coherence and does introduce something new. This dynamic creative process is a great challenge to computational systems since it requires structural discipline as well as adaptive exploration. Initial computational systems of music generation were largely based on rule systems that used music theory. Although these techniques guaranteed the tonal accuracy and formalism, they were not flexible and could probably deliver fixed and predictable results Chirico et al. (2021). With the development of machine learning, in particular, sequence modeling algorithms, including recurrent neural networks (RNNs), variationalautoencoders (VAEs), and transformer-based models, it became possible to learn musical patterns based on large corpora using data. These models have been shown to have great potential of local melodic and harmonic dependency capture Kilty et al. (2023). Nevertheless, they are mostly optimized by supervised learning goals, which are concerned with what comes next as opposed to music decision-making. This means that such systems are likely to be weak in the areas of long-term structure, expressive control, and adaptive creativity, which are important components of improvisational performance. Reinforcement learning (RL) provides an entirely different approach that is very consistent with cognitive mechanisms of improvisation Dowlen et al. (2022).

In RL, an agent is able to learn by interacting with an environment by performing actions, providing feedback as rewards, and observing consequences. This learning process of trial and error is similar to human musicians who practice and experiment their improvisational skills and react to the audience. Using musical improvisation as a series of decision making problems, RL also allows models to go beyond passive pattern replication to goal oriented, context sensitive musical behaviour. The application of reinforcement learning to musical improvisation is done by modeling the generation of music as a Markov decision process. Examples of information that can be encoded by musical states include the current pitch, harmonic context, rhythmic position and history of phrases and the actions are the selection of notes, altering articulation or extending melodic phrases Keady et al. (2022). Most importantly, reward functions can be configured to add several musical goals, such as tonal stability, rhythmic alignment, stylistic compliance, and creative variation. This freedom enables RS systems to optimize conflicting objectives, e.g. harmonic coherence and exploration of new melodic concepts. Reinforcement learning in music is a rather unexplored field, although it is conceptually suitable in comparison with supervised generative models Reid-Wisdom and Perera-Delcourt (2022). Among the challenges are the design of musical reward signals which are meaningful, the dimensionality of musical action spaces is high, and aesthetic evaluation is subjective.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Overview of musical improvisation theory (tonality, harmony, rhythm, phrasing)

The musical improvisation has a strong theoretical basis of combining the structural rules and expressive freedom. Tonality gives the basic structure of pitch, which has a central key or modal center according to which notes are chosen, and the basis of perceptual stability is created. Improvisers usually insist on scale tones, chord tones and tension-resolution patterns in order to preserve the tonal integrity but create expressive variations in the form of chromaticism or modal substitution Clements-Cortés and Yu (2021). Harmony determines the vertical aspect of improvisation, the chord progressions and the rhythm of harmony play a role in determining melodies. Experts improvising foresee alteration of chords, define harmonic roles and use replacements or additions to add richness to music without breaking the style conventions. The rhythm is very important in improvisation as it organizes time flow and expressive time. In addition to metrical form, improvisers play around with syncopation, swing, tempo change, rhythmic displacement to generate groove and momentum Foubert et al. (2021). Rhythmic motifs are frequently repeated and developed, giving the passages in the improvisation continuity. Phrasing is the integration of melodic contour, grouping of rhythm and expression into logical musical ideas. Improvised phrases tend to follow conversation pattern, which includes structures of call and response, tension building, climactic points and resolution. The application of breath, pause and silence is controlled to create musical stories Riabzev et al. (2022).

2.2. Machine Learning Approaches to Generative Music (RNNs, Transformers, VAEs)

Generative music systems have also been greatly improved through machine learning where a model is able to learn the structure of music by analyzing data. Some of the earliest deep learning models in generation of music were the recurrent neural networks (RNNs), including the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) networks. They are appropriate in modeling melodic sequences and rhythmic patterns because they are capable of capturing the temporal dependencies Begun et al. (2023). Nevertheless, long-term coherence can be a significant problem in the RNN-based models, and they tend to produce repetitive or fluctuating music when trained on long musical fragments. Variationalautoencoders (VAEs) presented a probabilistic latent music generation space that enables interpolation and variational as well as style control. VAEs facilitate the exploration of musical phrases as well as controlled generation by learning compact representations of musical phrases Jones et al. (2024). However, because of the reconstruction faithfulness, VAEs often do not have musical intentionality, and thus yield statistically possible but musically dissolved results during improvisation. A little later, transformer architectures have gained prominence with their self-attention mechanisms that are useful in modelling long-range dependencies and hierarchical musical structure Campbell et al. (2024). Transformers are efficient at gathering relationships between phrases, sections and harmonic progressions all over the world.

2.3. Existing Reinforcement Learning Models for Sequential Artistic Tasks

Learning to reinforce has been studied in other sequential artistic fields whereby creativity is played out as a series of decisions that are interdependent. In music Early use of RL In this context, initial RL systems were used with rule-based composition and accompaniment systems, with agents trained to choose notes or chords that would give maximum predetermined musical rewards. These systems showed that it was possible to frame the process of music generation as a decision-making process, at the cost of basic state representations and manually designed reward functions Dower (2022). In addition to music, RL has been used in the generation of visual art, dance choreography, procedural animation and interactive storytelling. In choreography generation, such as the RL agents, motion sequences are acquired that are smooth, consistent in style, and physically possible. Likewise, in creative writing and storytelling, an RL has been applied to maximize narrative coherent and readership with acquired reward predictors. Table 1 is a summary of the reinforcement learning methods on musical improvisation and generative music. These researches demonstrate the ability of RL to deal with long-horizon dependencies and tradeoffs among a variety of often conflicting goals. More recently, deep reinforcement learning methods have been applied to musical tasks that combine neural networks with the RL models of Deep Q-Networks (DQN) and policy gradient methods Afchar et al. (2022).

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary on Reinforcement Learning in Musical Improvisation and Generative Music |

|||||

|

Musical Domain |

Model Type |

Learning Paradigm |

State Representation |

Action Space |

Objective |

|

Algorithmic Music |

Rule-based RL |

Reinforcement Learning |

Pitch and duration |

Note selection |

Tonal correctness |

|

Jazz Improvisation Messingschlager and Appel (2023) |

GenJam |

RL + GA |

Chord context |

Phrase selection |

Listener feedback |

|

Melody Generation |

Tabular RL |

Reinforcement Learning |

Pitch intervals |

Next note |

Harmonic fitness |

|

Symbolic Music |

RNN + RL |

Hybrid (SL + RL) |

Melody history |

Note probabilities |

User preference |

|

Polyphonic Music Agostinelli et al. (2023) |

Transformer |

Supervised Learning |

Token sequences |

Next token |

Likelihood maximization |

|

Music Composition |

RL Agent |

Deep RL |

Harmonic features |

Pitch-duration pairs |

Tonal stability |

|

Generative Music |

VAE |

Unsupervised Learning |

Latent embeddings |

Sample decoding |

Reconstruction loss |

|

Melody Improvisation |

DQN |

Deep RL |

Scale and chord states |

Interval moves |

Music theory rules |

|

Creative AI Music |

Survey |

Mixed Methods |

— |

— |

— |

|

Expressive Performance |

PPO |

Policy Gradient RL |

Temporal dynamics |

Expressive timing |

Smoothness reward |

|

Jazz Soloing |

Transformer + RL |

Hybrid RL–DL |

Phrase embeddings |

Phrase actions |

Novelty + harmony |

|

Interactive Music |

Multi-agent RL |

Deep RL |

Performer–agent state |

Call–response actions |

Engagement score |

|

Musical Improvisation |

PPO + Hybrid RL |

Deep RL + Generative Models |

Melody, harmony, rhythm |

Notes, phrases, ornaments |

Tonality, creativity,

coherence |

3. Theoretical Foundations of RL for Music

3.1. Markov decision processes for musical state–action formulation

Markov decision processes (MDP) usually formalize sequential decision-making problems, and have become a natural abstraction of musical improvisation. An MDP is comprised of states, actions, transition dynamics, and rewards, which can both be mapped to musical contexts sensibly. The state in music generation of improvisation is the given musical situation, frequently capturing, in a form of encoding, pitch class, history of melodic intervals, harmonic context, metrical location, tempo, and phrase structure. These depictions of local musical events as well as broader structural cues affecting ensuing choices are what is depicted. Action space determines the number of possible musical options that the agent can make at a given time step. These actions can involve choosing the next note or chord, defining rhythmic length, ornamentation or deciding whether to continue the phrase or not. Actions may be more abstract (e.g. MIDI notes or scale degrees) and higher-level more abstract like motif selection. The transition of the states is related to the development of musical context after every action based on the changes in harmony, rhythm, and melodic progression. The model of musical state-action improvisation is in Figure 1, which is a Markov decision process. Markov property is based on the idea that future music outcomes are determined by only state and action, and not the history of the entire performance.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Markov Decision Process Framework for Musical State–Action

Modeling in Improvisation

Although the long-term dependencies are observed in music, example state representations would allow approximating this property by storing enough contextual memory.

3.2. Reward Design Strategies for Tonal Stability, Creativity, and Temporal Coherence

The key problem of implementing the concept of reinforced learning to musical improvisation is the design of rewards since they directly encode both the aesthetic and structural goals. Rewards Tonal stability rewards entice the agent to choose those notes that agree with the dominant key, mode, chord, and to strengthen harmonic consonance and suitable tensionto-resolution interactions. These rewards are usually based on the rules of music theory, such as belonging to a scale, giving emphasis to the tones of the strong beats in a chord, and punishing unresolved dissonance. On the contrary, the rewards supporting creativity encourage originality and expressive diversification. These can encourage melodic variety, intervallic experimentation, mutation of motif or non-repetitive use. In order to prevent random, the rewards of creativity are usually tried to equalize with stability constraints so that innovation can take place within the stylistically significant frames. The novelty are usually quantified using the statistical measures e.g. the entropy or distance to training distributions. The rewards of Temporal coherence are rhythmic coherence, continuity in phrases and structural flow over time. These rewards can take note of metrical alignment, recurrence of rhythmic patterns as well as the proper length of phrases. Punishing sudden shift of rhythm, or overly divided phrases, assists in the sustenance of the musical intelligibility. Subjective aspects like expressiveness and musicality have been found to be increasingly trained in learned reward models on top of human preferences or expert annotations. Reinforcement learning systems can provide approximations of multifaceted musical judgement by jointly using rule-based, data-driven and listener-inspired rewards, to direct agents to improve their own improvisations in a manner that is coherent, creative and stylistically based.

3.3. Exploration–Exploitation Balance in Improvisational Contexts

The exploration and exploitation balance are essential to reinforcement learning but is especially essential in musical improvisation. Exploitation is an act of choosing those actions that are known to be highly rewarding, e.g. harmonically safe notes or known rhythmic patterns. This practice guarantees the musical unity and stylistic cohesion, but leads to possible repetitive or predictable improvisations. On the contrary, exploration makes the agent attempt less confident actions and may lead to the creation of new melodic thoughts, rhythmic variations, or expressive gestures. In improvisation, successful exploration should be structured as opposed to an accidental process. Controlled variability and maintaining musical plausibility can be performed with the help of ε-greedy policies, entropy regularization and stochastic policy gradients. It can be used to minimize the amount of randomness in adaptive exploration schedules as learning proceeds, and this is more reminiscent of how human musicians develop their improvisational vocabulary with time. Context-dependent exploration plans can also change exploration rates depending on musical position, and thus be more experimental at cadential points, or during transitions or solos. The exploration versus exploitation also has a connection with the perception of the audience and aesthetic fulfillment.

4. Proposed RL-Based Improvisation Framework

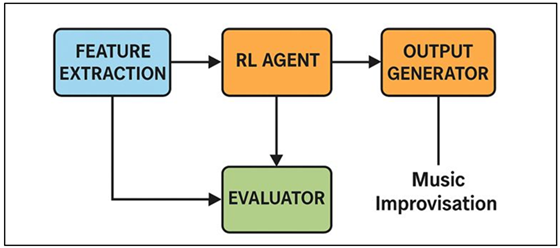

4.1. System architecture (feature extraction, RL agent, evaluator, output generator)

The suggested reinforcement learning-based improvisation framework is a modular architecture, which bonds musical perception, decision-making, evaluation, and generation into one pipeline. Its feature extraction module accepts music in the form of symbols or sound-based musical performances by converting raw records of improvisation performance into a structured format (pitches, intervals, chord names, rhythmic grids, phrase boundaries). This module makes sure that information regarding music that is relevant is recorded in a way that can be learned consecutively whilst not losing their stylistic nuances.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Reinforcement Learning–Based System Architecture for

Musical Improvisation

The RL agent is at the center of the system and monitors the current musical situation and chooses the actions based on an acquired policy. In Figure 2, reinforcement learning architecture will empower musical improvisation systems to be adaptive. The agent is deployed on the deep neural networks to manage high dimensional state spaces and complicated temporal dynamics. It is constantly revising its policy by engaging with the environment to enable adaptive improvisational action as time progresses. The evaluator module is the feedback system which calculates the rewards on the basis of tonal accuracy, rhythmic accuracy, a measure of creativity, and stylistic consistency.

4.2. State Representation: Melodic Intervals, Harmonic Context, Rhythmic Patterns

The representation of the state is a paramount design choice in musical improvisation based on the reinforcement learning since it determines the information about the agent when he/she makes a decision. The proposed framework does not use the absolute pitch values alone, but in preference, it focuses on the melodic intervals thereby, indicating the relative movement of pitch, and more perceptual and stylistic qualities in improvisation. Representing melodic contour across key is also learned without reference to key with the help of interval-based representations. The harmonic context is added with the help of the following features: labels of current chords, labeling of scales, indicators of functional harmony, and a history of chord progression. The information allows the agent to predict the harmonic changes and choose the notes that either go with the harmony beneath or deliberately contradict it. The explicit model of short-term harmonic memory enables the estimation of long-range dependence in the Markov decision process model. Metrical position, duration of notes, timing of onsets and rhythmic motif embeddings are used to represent rhythmic patterns. The characteristics have enabled the agent to preserve time, observe meter, and build rhythmic identities within phrases. More evidence of higher level structural recognition is provided by phrase boundary indicators and beat-level encoding.

4.3. Action Space: Note Selection, Phrase Continuation, Ornamentation Strategies

The action space is the space that specifies the available musical options the reinforcement learning agent can make on each step of the decision-making process and, consequently, directly determines the expressiveness of the produced improvisation. In the suggested framework, note selection is the most important action category, which enables the agent to select either pitch classes, scale degrees, or relative intervals. This abstraction helps to have harmony awareness and to have stylistic plasticity but limit actions to musical meaningful alternatives. In addition to individual notes, a decision space on phrase continuation also exists allowing the agent to decide whether to continue with an ongoing melodic idea, to add variation, or to end a phrase. These actions facilitate upper level musical form as it enables one to control the length of a phrase, repetition and development. Decisions at a phrase level aid in preventing highly disordered improvisations and promote musical accounts. The framework is supplemented with ornamentation strategies as optional actions in order to increase expressiveness.

5. Training Methodology

5.1. Dataset preparation from professional improvisation recordings

Musical improvisation reinforcement learning models should be trained using a carefully selected dataset in terms of authentic stylistic and expressive practices. In the suggested methodology, datasets will be created based on the recordings of professional improvisation in various genres which include jazz, classical cadenzas, folk traditions, and modern instrumental solos. A combination of musicological heuristics and automated onset detection are used to divide audio recordings into meaningful musical units, such as phrases, motifs and segments. Symbolic representations, if possible, like MIDI or annotated scores are synchronized with audio so that they are more accurate. Melodic intervals, distribution of pitch-classes, harmonic patterns, rhythmic patterns and standout signs are then derived using feature extraction. The harmony analysis tools and beat-tracking algorithms are used to find the labels of the chords and the metrical positions. The stylistic regularity is done by grouping of the recordings according to the genre, tempo span and the tonal system, allowing controlled training and assessment. Techniques used to augment data associated with transposition, rhythmic scaling and motif variation are used to enhance the generalization whilst maintaining musical semantics. Importantly, the dataset is not considered like in supervised learning as a source of desired outputs but considered as a reference environment which guides state initialisation, transition dynamics, and criteria used to evaluate the performance.

5.2. Learning Algorithms: Q-Learning, PPO, DQN, and Hybrid RL–Deep Learning Models

The training methodology investigates various reinforcement learning algorithms with the view of considering whether they are appropriate in musical improvisation work. Q-learning is a prototype method, learning functions of states-actions values, which approximate long term musical reward. Although it works well in small and discrete action spaces, the classical Q-learning finds it difficult to scale and continuous musical representations. To overcome this shortcoming, Deep Q-Networks (DQN) are used, where neural networks are used to estimate Q-values in high dimensional state spaces. DQN can be sensitive to reward sparsity and exploration methods as well as learn complex musical features. Improvisation is well adapted to policy-based approaches and especially Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) since they are stable and can deal with stochastic policies. PPO provides fine-grained control and easy exploration of action distributions, is expressively variably, and convergence-reliable. Under this arrangement, supervised models offer good musical priors and RL optimizes the decision making process by taking into consideration feedback on rewards.

6. Results and Analysis

6.1. Quantitative performance comparison across models

Quantitative assessment was done to evaluate the performance of the Q-learning, DQN, PPO, and hybrid RL–deep learning models under several musical criteria. Measures involved tonal accuracy, harmonic alignment, rhythmic consistency, phrase coherence and melodic diversity. The findings show that classical Q-learning had stable performance with limited success because state-action representation was limited. DQN was more harmonic correct and rhythmically stable and showed repetition in longer sequences. PPO was always better than the value-based approaches with higher scores in melodic diversity and long-term coherence because of its stochastic policy optimization.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Objective Evaluation Metrics for Improvisation Models |

||||||

|

Model |

Tonal Accuracy (%) |

Harmonic Alignment (%) |

Rhythmic Consistency (%) |

Phrase Coherence Score |

Melodic Diversity Index |

Avg. Reward |

|

Q-Learning |

78.4 |

75.1 |

72.6 |

0.61 |

0.42 |

0.58 |

|

DQN |

84.7 |

82.9 |

80.3 |

0.69 |

0.51 |

0.66 |

|

PPO |

89.6 |

88.2 |

86.7 |

0.78 |

0.63 |

0.75 |

|

Hybrid RL–DL |

93.1 |

91.8 |

90.4 |

0.85 |

0.71 |

0.82 |

The quantitative aspects of the performance improvement of reinforcement learning models with increasing expressiveness and structural knowledge are presented in Table 2. A tonal accuracy of 78.4 per cent and rhythmic consistency of 72.6 per cent, though with a fairly small phrase coherence value of 0.61, all demonstrate that Q-learning does not have the ability to model long-term musical structure. Figure 3 presents tonal, harmonic and rhythmic performance comparison among reinforcement learning models.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Comparative Analysis of Tonal, Harmonic, and Rhythmic

Performance Across RL Models

In switching to DQN, tonal accuracy is improved by 6.3pp (78.4% to 84.7%), and harmonic alignment by 7.8pp (75.1% to 82.9%), which is characterized by superior contextual learning using deep value approximation. The reinforcement learning model performance is illustrated in Figure 4 in terms of musical generation metrics. The PPO model also increases the tonal accuracy to 89.6, which is an 11.2-point improvement over Q-learning, and melody diversity, which grows 0.42 to 0.63 and is improved 50 percent, indicating better exploratory behavior. Phrase coherence also increases significantly (0.61 to 0.78), which also reflects the continuity of music on a longer time.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Reinforcement Learning Model Performance

Overall performance of the Hybrid RL-DL model is the highest with tonal accuracy of 93.1 percent and rhythmic consistency of 90.4 which are 3.5 and 3.7 higher than PPO. It has been shown that its average reward of 0.82 is an improvement of 41.4% compared to Q-learning (0.58). Such numeric patterns prove that hybrid reinforcement learning models are the most effective to balance musical accuracy, expressiveness and creative diversity in musical improvisation generation.

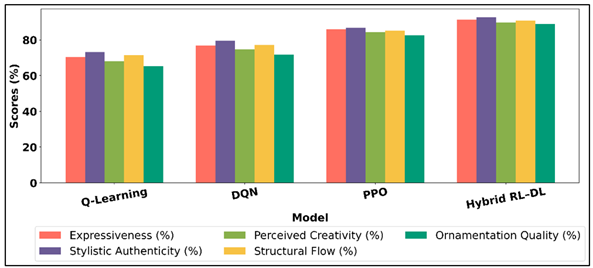

6.2. Qualitative Analysis of Generated Improvisational Sequences

Qualitative research centered on the expressiveness of music, its stylistic authenticity and perception of improvisations made by the listeners. The sequences generated by Q-learning models were usually coherent and predictable and tended to use safe melodic patterns with a restricted amount of variation. DQN-improvisations were more refined in terms of clarity but lacked expressiveness at times. PPO-generated sequences had a higher rhythmic flexibility, dynamic phrasing and balanced tension-resolution behavior that were strongly resemblant to human improvisational behaviors. Expert listeners judged hybrid RL /deep learning results as the most convincing and believed they had a noticeable stylistic identity, developed phrases in a natural manner, and utilized ornamentation to their advantage.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Expert and Listener-Based Qualitative Assessment Scores |

|||||

|

Model |

Expressiveness (%) |

Stylistic Authenticity (%) |

Perceived Creativity (%) |

Structural Flow (%) |

Ornamentation Quality (%) |

|

Q-Learning |

70.5 |

73.2 |

68.1 |

71.4 |

65.3 |

|

DQN |

76.8 |

79.5 |

74.6 |

77.2 |

71.8 |

|

PPO |

85.9 |

86.7 |

84.3 |

85.1 |

82.6 |

|

Hybrid RL–DL |

91.4 |

92.6 |

89.8 |

90.7 |

88.9 |

Table 3 shows the scores on expert and listener-based qualitative assessment which are used to express perceptual and aesthetic judgments on the created improvisational sequences. Figure 5 indicates the performance comparison of expressiveness of music models based on RL. Q-learning model scores rather modest ratings, expressiveness 70.5% and perceived creativity 68.1, which suggests musically consistent but emotionally inhibited results.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Expressiveness and Stylistic Performance Comparison

Across RL-Based Music Models

The lowest is ornamentation quality at 65.3 which implies the lack of surface-level decoration and expressiveness. DQN model is steadily improving in all dimensions as the expressiveness improved by 6.3 percentage to 76.8 percent and the stylistic authenticity grew to 79.5 percent. Perceived creativity increases 6.5 above the Q-learning, which indicates a better variation and structural visibility. There is also an increment in structural flow to 77.2% which means that the transition between phrases is more fluid. PPO model is a strong qualitative leap, with the expressiveness and the stylistic authenticity of 85.9 per cent and 86.7 per cent respectively. The perceived creativity is 84.3, which is a 16.2-point better than Q-learning. The quality of ornamentation also increases significantly to 82.6, which also points to the capability of PPO to handle the expressive decisions on a micro-level.

7. Conclusion

This paper has discussed how reinforcement learning can be effective and conceptually consistent as the model of musical improvisation. Reinforcement learning, in contrast to traditional supervised generative methods which give primary attention to pattern replication, allows adaptive goal-directed decision-making in music which is more reflective of the cognitive and performative mechanisms of human improvisers. The proposed framework is able to combine melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic awareness into one learning paradigm by developing improvisation as a sequence of decision making problem as part of a Markov decision process. One of the strengths of this work has been the construction of musically informed representations of states and multi-objective reward functions which trade off tonal stability, temporal coherence, stylistic uniformity, and creative exploration. The combination of rule based, listener based and model based feedback enables the learning agent to internalize objective musical structure as well as subjective esthetic judgment. Experimental testing shows that improved types of reinforcement learning, especially policy-based and hybrid RL deep learning models are superior to traditional type of value based models in terms of creating expressive, coherent and stylistically realistic improvisations. Both qualitative and quantitative findings also demonstrate the significance of exploration/exploitation control in creative systems, and that structured exploration reduces novelty without affecting musical intelligibility. The results indicate that the reinforcement learning not only positively influences the technical quality of composition improvisations but also promotes the expressiveness variation and structural growth in the long term.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Afchar, D., Melchiorre, A., Schedl, M., Hennequin, R., Epure, E., and Moussallam, M. (2022). Explainability in Music Recommender Systems. AI Magazine, 43(2), 190–208. https://doi.org/10.1002/aaai.12056

Agostinelli, A., Denk, T. I., Borsos, Z., Engel, J., Verzetti, M., Caillon, A., Huang, Q., Jansen, A., Roberts, A., Tagliasacchi, M., et al. (2023). MusicLM: Generating Music from Text (arXiv:2301.11325). arXiv.

Begun, S., Bautista, C., Mayorga, B., and Cooke, K. (2023). “Young Women my Age Really Need Boosts Like This”: Exploring Improv as a Facilitator of Wellness Among Young Women of Color. Health Promotion Practice, 24(6), 1133–1137. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248399221130726

Campbell, S., Dowlen, R., Keady, J., and Thompson, J. (2024). Care Aesthetics and “being in the Moment” Through Improvised Music-Making and Male Grooming in Dementia Care. International Journal of Education and the Arts. In press.

Chirico, I., Ottoboni, G., Valente, M., and Chattat, R. (2021). Children and Young People’s Experience of Parental Dementia: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 36(7), 975–992. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5542

Clements-Cortés, A., and Yu, M. T. (2021). The Mental Health Benefits of Improvisational Music Therapy for Young Adults. Canadian Music Educator, 62(3), 30–33.

Dower, R. C. (2022). Contact Improvisation as a Force for Expressive Reciprocity with Young Children who Don’t Speak. Learning Landscapes, 15(1), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.36510/learnland.v15i1.1065

Dowlen, R., Keady, J., Milligan, C., Swarbrick, C., Ponsillo, N., Geddes, L., and Riley, B. (2022). In the Moment with Music: An Exploration of the Embodied and Sensory Experiences of People Living with Dementia During Improvised Music-Making. Ageing and Society, 42(11), 2642–2664. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X21000210

Foubert, K., Gill, S. P., and De Backer, J. (2021). A Musical Improvisation Framework for Shaping Interpersonal Trust. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 30(1), 79–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2020.1788627

Jones, L., Cullum, N., Watson, R., Thompson, J., and Keady, J. (2024). “Only my Family Can Help”: The Lived Experience and Care Aesthetics of Being Resident on an NHS Psychiatric/Mental Health Inpatient Dementia Assessment Ward—A Single Case Study. Ageing and Society. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X24000096

Keady, J., Campbell, S., Clark, A., Dowlen, R., Elvish, R., Jones, L., Kindell, J., Swarbrick, C., and Williams, S. (2022). Re-Thinking and Re-Positioning “Being in the Moment” within a Continuum of Moments: Introducing a new Conceptual Framework for Dementia Studies. Ageing and Society, 42(3), 681–702. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X20001014

Kilty, C., Cahill, S., Foley, T., and Fox, S. (2023). Young Onset Dementia: Implications for Employment and Finances. Dementia, 22(1), 68–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/14713012221132374

Messingschlager, T. V., and Appel, M. (2023). Mind Ascribed to AI and the Appreciation of AI-Generated Art. New Media and Society, 27(6), 1673–1692. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448231200248

Reid-Wisdom, Z., and Perera-Delcourt, R. (2022). Perceived Effects of Improv on Psychological Wellbeing: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 17(2), 246–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2020.1856016

Riabzev, A., Dassa, A., and Bodner, E. (2022). “My Voice is Who I am”: Vocal Improvisation Group Work with Healthy Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Voices: A World Forum for Music Therapy, 22(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.15845/voices.v22i1.3125

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.