ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

AI for Preserving Indigenous Folk Art Patterns

Muthukumaran Malarvel 1![]()

![]() ,

Wamika Goyal2

,

Wamika Goyal2![]()

![]() ,

Sadhana Sargam 3

,

Sadhana Sargam 3![]() , Kapil Mundada 4

, Kapil Mundada 4![]() , Dr. A. Viji Amutha Mary 5

, Dr. A. Viji Amutha Mary 5![]()

![]() ,

Ashwika Rathore 6

,

Ashwika Rathore 6![]()

![]()

1 Department

of Computer Science and Engineering, Aarupadai Veedu Institute of Technology,

Vinayaka Mission’s Research Foundation (DU). Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

2 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

3 Assistant Professor, School of Business Management, Noida International

University, India

4 Department of Instrumentation and Control Engineering Vishwakarma

Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037, India

5 Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Sathyabama

Institute of Science and Technology, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

6 Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science and Information

Technology, Siksha 'O' Anusandhan (Deemed to be University), Bhubaneswar,

Odisha, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The indigenous

folk art traditions represent centuries of cultural wisdom, community

belonging, symbolism, and craftsmanship which are specific to a certain

region. The continuity of these visual heritage systems is however endangered

by fast urbanization, erosion of artisanal transmission and little digital

documentation. The presented paper is an AI-based model of the preservation

of indigenous folk art patterns by creating systems of data, developing

features, and using motifs to reconstruct the object. The suggested approach

combines controlled imaging pipelines based on museums, archives, craftsmen

and field-based surveys to come up with a very enriched, metadata-conformant,

cultural heritage information dataset. Annotation protocols represent the geometry

of the motifs, stroke behavior, chromatic palettes, material references and

regional semantic attributes that allow the structured cultural

representation. The system identifies the discriminative visual features,

which are used to define the various folk art traditions, using deep learning

models DNNs, ViTs and multimodal style-embedding models. Moreover, encoding

symbolic motifs allows comparing styles crossly, and clustering patterns as

well as synthesizing them using AI-like synthesis models. Experimental

findings indicate that there is a high performance in the motif recognition

accuracy, reconstruction fidelity and stylistic consistency indicating a

possibility of AI to support artisans, researchers and cultural institutes.

The discussion showcases the importance of the ethical aspects of the

community involvement, cultural sensitivity and responsible practices of

digitization, not just those related to the technical developments. On the

whole, the current work adds a scalable, culturally sensitive AI system with

the purpose of preserving the indigenous visual knowledge and guaranteeing

its continued transfer to the subsequent generations. |

|||

|

Received 05 June 2025 Accepted 19 September 2025 Published 28 December 2025 Corresponding Author Muthukumaran Malarvel, muthukumaran.avcs0103@avit.ac.in

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i5s.2025.6900 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Indigenous Folk Art Preservation, Cultural Heritage

AI, Motif Recognition, Deep Learning, Pattern Reconstruction |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Some of the earliest forms of visual language still extant in human civilization, indigenous folk art is seen as an expression of social beliefs, mythology, knowledge of craft, and collective memory of various communities. Every motif, stroke, color scheme and geometric composition has underlying strata of encoded cultural significance that have been passed on through generations of oral teaching, apprenticeship and practice. Nevertheless, globalization, industrial production, depopulation and slow erosion of skilled crafts have been challenging many of these traditions to unprecedented levels. With younger generations moving on to urban work and commercial forces of design homogenizing aesthetics, various folk art possibilities are in danger of disappearance, at least in part. This cultural susceptibility should be addressed with a system of digital preservation initiatives that have the potential to preserve, interpret, and rejuvenate indigenous motifs with complete faithfulness and contextual acuity. The use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) as the visual recognition tool, pattern analysis, and generative modeling tool has become a potent force that can be used to revolutionize the work of cultural heritage preservation. It is now possible to teach AI systems complex relationships between colors, textures, brushstroke patterns, symbolic structures, and regional styles with the advent of deep learning architectures, including Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Vision Transformers (ViTs), and multimodal generative models Khan (2024). Such abilities allow automatic recognition of the folk art patterns and style features grouping, as well as restoration of the damaged or fragmented paintings. In addition, AI can support digital archiving, as it helps museums, researchers, and cultural institutions to catalogue and search large collections of images, thus saving on manual labour and enhancing the consistency of metadata Leshkevich and Motozhanets (2022). In spite of them, the use of AI in preserving folk art has not been fully investigated in comparison to other fields like natural image classification, medical imaging, and commercial design.

Folk art poses special problems: there is a lot of stylistic heterogeneity, little or unbalanced dataset, differences in artisan styles, and annotating such works culturally. Motifs in turn represent non-Western visual grammars which mainstream computer vision models are not optimized to. Also, any technological intervention should be informed by ethical issues like proper respect of community ownership, cultural misappropriation and meaningful involvement of artisans Marchello et al. (2023). Thus, AI-based conservation of indigenous folk art patterns needs not just technical quality but also systems that are based on cultural sensitivity and heritage custodianship. The study fills these gaps by suggesting an all-encompassing AI-powered approach to the capture, analysis, and reconstruction of the patterns of indigenous folk art. The research starts with the creation of the culturally sound dataset that is gathered in museums, digital archives, communities of artisans, field surveys, and heritage facilities Ghaith and Hutson (2024). The annotation protocols are well created in order to record the geometry of motifs, their chromatic style, and the shape of strokes, references to materials, and identities of regions. The metadata standards are used to guarantee interoperability with larger databases within the cultural heritage. The high-level feature extraction methods, which use CNNs, ViTs, and style-embedding networks, permit the description of motifs on the levels of texture, symbolism, and artistic variation Zhong et al. (2021). Generative models aid in the reconstruction of motifs and pattern reproduction without losing the stylistic authenticity.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Traditional approaches to documenting folk art motifs

Historical, traditional documentation of the indigenous folk art motifs have traditionally been implemented by use of manual, community-based and ethnographic methods. Field visits were usually made by researchers, anthropologists, and art historians to artisan communities, where it was documented in the form of sketches, photographs, interviews and handwritten catalogues. These methods focused more on the richness of situations - to capture not only motifs but also tales, ritual meanings, methods of production, and the process of teaching across generations Song (2023). The physical objects of folk art, together with the metadata describing them have frequently been held by museums and cultural archives. Much of this documentation is however basically scattered, not complete, or not in standard formats, which complicates large-scale comparative analysis. The artisans themselves have been very fundamental in passing of the motifs in terms of apprenticeship models, where knowledge is incarnated and not in writings Xu et al. (2024). This verbal and practical conveyance maintains the originality of motifs yet it is susceptible to interferences by urban migration, diminishing interest in young generation and disappearance of traditional means of livelihood. There have been print repositories including community books, regional art catalogues, and pattern manuals, which have tried to standardize motifs, but many are lost or not available to the general public or are of a low-resolution image Ye (2022). But on the whole, traditional forms of documentation have a rich and cultural depth, but cannot meet the modern demands of scalability, international accessibility and digital storage especially as factors of cultural homogenization and socio-economic transformation continue to threaten folk art traditions.

2.2. Computer Vision Applications in Cultural Artifact Recognition

Computer vision has also been used in a growing body of applications to the recognition, classification, and retrieval of cultural objects, and has been used to perform automated analysis of historical textiles, pottery, manuscripts, architecture, and sculptural motifs. Often-used techniques, such as feature detection (SIFT, HOG), texture analysis, and shape modeling, have been heavily used to identify patterns, categorize objects by area or time and identify the similarities in styles between collections Chen and García (2022). CNN-based models like ResNet, Inception and EfficientNet have (with the introduction of deep learning) significantly advanced the accuracy of recognition through learning hierarchical visual feature representations, including strokes, symmetry structures and decoration, which are typical of traditional art forms. Later, multimodal embeddings and contrastive learning models (e.g., CLIP) alongside Vision Transformers (ViTs) have increased the abilities to make comparisons between images based on stylistic domains and match motifs on the text description basis. It has been used in the detection of forgeries, reconstruction of damaged artifacts, colorization of historical images, and motifs extracted out of a complicated background. A number of digital humanities projects have embraced the use of these tools in heritage conservation, including automatic transcription of manuscripts, search of textile designs, and categorization of archaeological shapes Amany et al. (2022). Nonetheless, the area of folk art recognition is underresearched because of the lack of data, large intra-class stylistic differences, and annotations that require cultural context. Altogether, computer vision provides good opportunities to scale-up and objectively analyze cultural artifact, yet the application to the native folk art traditions needs adaptation Morlotti et al. (2024).

2.3. AI-Driven Cultural Preservation Frameworks Globally

Artificial intelligence-based cultural protection efforts have been on the rise around the globe with governments, museums, and research centers exploring solutions to protect intangible and tangible heritage on a large scale. Google Arts and Culture is one project using deep learning to digitize high-resolution artworks, tag artworks automatically, and explore artworks with an interactive visual interface. Programs funded by UNESCO have investigated machine learning applications in preserving linguistic, retrieving threats to music, and storytelling on the internet Bosco et al. (2021). Japan In Japan, AIs have been used to categorize Ukiyo-e woodblock prints, whereas in China, the deep learning models helped with restoring ancient murals and analysing historical calligraphy. CNNs and GANs are applied in the cultural heritage digitization process in Europe to restore damaged objects, as well as recreate lost motifs and improve archival images. The learning and generation of culturally inspired artworks, re-creation of lost patterns, and the provision of educational interfaces with the introduction of heritage motifs to younger audiences have also been implemented using generative models, including GANs and diffusion networks Janas et al. (2022). Multimodal AI systems combine visual, written, and historical metadata to have a more thorough culture with the ability to find patterns and compare styles across centuries. Along with these improvements, there are still these issues as cultural appropriation, imbalanced access to technology, and a lack of engagement with indigenous communities Trigona et al. (2022). Ethical constructs focus on participative design, rights to own cultural data, data sovereignty, and visible AI usage. Table 1 is a summary of AI-based solutions towards the preservation of cultural heritage and folk art. Together, these initiatives around the world are illustrative of the cultural preservation power of AI, but the necessity to have community-based technologies with cultural foundations.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary of Related Work on AI-Driven Cultural Heritage and Folk Art Preservation |

|||

|

Framework Title |

Region Focus |

Dataset Source |

Contribution to Present

Study |

|

Computer Vision in Indian

Tribal Art Recognition |

Indian Warli&Gond Art |

Local Museum Archives |

Foundation for automated

motif detection |

|

Deep Learning for Cultural

Artifact Recognition Shah et al.

(2023) |

Chinese Ceramic Motifs |

Heritage ImageNet Subset |

Inspires deep visual

heritage analysis |

|

AI Restoration of Ukiyo-e

Prints |

Japanese Traditional Prints |

Edo-period Museum Dataset |

Supports generative

restoration design |

|

Folk Pattern Digitization

through Feature Encoding |

Indian Madhubani Art |

Artisan Scanned Drawings |

Demonstrates

traditional-to-digital pipeline |

|

Semantic Tagging of Cultural

Artifacts Yang et al.

(2023) |

Brazilian Indigenous Crafts |

National Heritage Portal |

Motivates semantic cultural

labeling |

|

Visual Transformers for Art

Recognition |

East Asian Paintings |

AsiaArt Benchmark |

Validates ViT adoption for

folk art |

|

Heritage Pattern

Classification via Deep CNNs Hojjati et al. (2024) |

South Asian Wall Murals |

Field Photography Dataset |

Baseline for region-based

analysis |

|

GAN-based Cultural Pattern

Regeneration |

Southeast Asian Textile

Motifs |

Digital Textile Archive |

Relevant for generative

synthesis |

|

Automated Heritage

Restoration Using Diffusion Models |

Korean Pottery Art |

Cultural Image Repository |

Supports AI-based

restoration accuracy |

|

AI-Assisted Tribal Art

Recognition |

Indian Tribal Murals |

FolkArt India Dataset |

Confirms hybrid model

superiority |

|

Visual–Textual Alignment for

Art Archives Arafin et al. (2024) |

Latin American Folk Crafts |

Museum Digital Archives |

Informs multimodal motif

embedding |

|

Style Embedding for

Historical Artworks |

Chinese Heritage Motifs |

UNESCO Dataset |

Validates latent-space

clustering |

|

AI for Visual Heritage

Management |

Indian Folk Sculpture |

Mixed Regional Dataset |

Extends hybrid learning to

art heritage |

|

AI for Preserving Indigenous

Folk Art Patterns |

Multiregional Folk Art |

Museums, Artisans, Field

Data |

Introduces unified cultural

AI preservation model |

3. Dataset Development and Collection

3.1. Sourcing images from museums, archives, artisans, and field surveys

The process of developing the dataset starts with the massive sourcing of indigenous folk art images in the various cultural repositories. Museums and heritage archives offer scans of preserved works of high-quality, which are controlled in lighting and provenance. The digitization teams in the archives coordinate to access image collections, exhibition documentation papers, and indexed collections. In parallel, the work with local craftsmen allows getting the most up-to-date motifs in the form of high-resolution photos of works under way, murals, and textile designs. In Figure 1, the flow of acquiring multisource images in indigenous folk art data sets is illustrated. The field surveys in the rural and tribal areas help to note the regional differences in colors, styles, and symbols which are not always represented in institutional sources.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Multisource Image Acquisition Flow for Indigenous

Folk Art Dataset Development

It is ethical because of a community involvement, and artisans are acknowledged by their contributions. Digitalization arrangements on the mobile level are used in capturing images on the spot with natural lighting without sacrificing the texture and pigment nuances of the surfaces.

3.2. Annotation Protocols for Motifs, Colors, Materials, and Regions

Annotation is important to the translation of the visual heritage to let machines read the information. Each picture is annotated on a variety of semantic planes: the structure of motifs, color scheme, the use of materials, locality. Annotations at the motif level include geometrical shapes, direction of strokes and repeating combinations of symbolic shapes (e.g., flora, fauna, ritual icons). Color tagging depends on the use of standard colors codes (RGB, HEX) and the creativity of the language used to maintain cultural appropriateness. Semantic accuracy and cultural integrity are achieved by having cultural experts and artisans on the annotation team. The hierarchical labeling schemes, which are backed up by annotation tools such as Labelbox or CVAT, enable the features of object-level and pattern-level annotation. This creates the basis of the power of supervised learning, clustering, and generative synthesis in folk art conservation systems by virtue of its multi-dimensional annotations.

3.3. Metadata Standards for Cultural Heritage Datasets

Standardization of metadata provides long term accessibility, interoperability and authenticity of digital folk art archives. Every record in the dataset is based on the internationally accepted standards, like Dublin Core, Europeana Data Model (EDM), and CIDOC-CRM, and adapted to the cultural motifs. The most frequently used core metadata are the title, creator, material, technique, location, cultural context and associated community. To support reproducibility, technical information such as the resolution, file type, capture conditions and date of digitization is ingrained in the file. Contextual metadata is the combination of the narrative descriptions, historical relevance, and the symbolism of the motifs based on the ethnographic documentation. Digital object identifiers (DOIs) and persistent identifiers (PIDs) are applied to ensure that traceability and proper attribution is possible. Interoperability with other global heritage databases can be increased by semantic enrichment with controlled vocabularies and ontologies, e.g. Getty AAT or Wikidata terms. Also, the consent, ownership, and cultural sensitivity restrictions are documented in ethical metadata fields. The coordination of the technical and ethical aspects of the dataset results in archival rigor and the cultural sovereignty of the indigenous people.

4. Feature Extraction and Pattern Representation

4.1. Visual characteristics of folk art: geometry, colors, strokes, textures

The patterns of folk art are known to have rich visual vocabularies with which they encode the cultural stories by using symbolic geometry, bright color schemes, unique brushwork, and material expression. Many of the indigenous artworks are based on geometric composition the principles of which include symmetry, repetition, and radial balance, which represent the cosmic harmony and social order. In Figure 2, architectural representation of visual characteristics in folk art among the indigenous population is shown. Mandalas, spirals, diamonds, and concentric circles are some of the motifs that tend to carry mythological or agricultural associations. The use of colors in folk art is heavily contextualized- based on natural colors and local materials.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Architectural Representation of Visual

Characteristics in Indigenous Folk Art

Tribal murals are predominantly warm and earthy and festive and ritual paintings are characterised by high-saturation contrasts. Depending on the tool and surface, such as fine linear brushwork on cloth or heavy finger or twig impressions on the wall, can display not only the artisan personal style, but also regional ancestry. The aspect of texture is important to the perception of depth and the authenticity of materials in that rough surfaces, overlaying pigments, or even cloth weaves add make the texture more tactile. All of these visual characteristics characterize the aesthetic imprint of every tradition. By quantifying them using computational measures, e.g. edge density, gradient orientation, color histograms, and entropy of textures, it is possible to objectively model stylistic diversity.

4.2. Deep Learning-Based Feature Extraction (CNNs, ViTs)

The method of deep learning has changed the automated analysis of folk art by allowing systems to learn complex, multi-level representations directly out of images. ResNet, VGG, and EfficientNet are examples of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), which are used to extract hierarchical visual features, including low-level edges and color gradients, high-level compositional features and motif clusters. Their convolutational filters in their filters reflect geometric patterns, brushstrokes and local color patterns that define folk traditions. The feature maps created by the intermediate layers are able to discern minor differences among similar motifs across different regions to provide exceptional classification and clustering. Nevertheless, CNNs are not always able to deal with long-range spatial dependencies of large or repetitive folk designs. Vision Transformers (ViTs) have developed as a better alternative to this. ViTs learn to model the global relationships between the elements of a motif through self-attention mechanisms that learn to interacting individual shapes to create the whole pattern. They are very good at finding symbolic symmetry, interwoven patterns and contextual clues in whole works of art. Hybrid CNNL ViT models are models that combine a localized convolutional perception model with a transformer-based contextual reasoning model, achieving a high precision of motifs recognition and style distinction. The models facilitate the discriminative (classification) and generative (reconstruction) processes, which is why they form the basis of AI-assisted preservation, reconstruction, and digital regeneration of indigenous folk art traditions.

4.3. Style Embeddings and Symbolic Motif Encoding

Alongside the visual recognition, AI systems should be able to reproduce the stylistic essence, symbolic language of folk art with the help of sophisticated representation systems like style embeddings and motif encoding. StyleGAN and CLIP-based encoders as well as contrastive autoencoders are all models that produce these embeddings, allowing the grouping of works of art based on regional ancestry or similarity of subject. As an example, a Warli, Madhubani, and Gond painting can take up different areas of the embedding space as each has a different compositional signature. This is furthered in symbolic motif encoding which converts cultural semantics into computational form. Symbolic vectors are encoded into symbolic vectors associated with cultural taxonomies or ontologies in the form of motifs (sun, tree of life, fish or peacock). This enables the visual form to be related to meaning to aid in semantic retrieval and interpretation by AI. By integrating visual and symbolic embeddings, it is possible to understand multimodally: that is, the models can see not only shapes but also cultural objects as motifs. The representations are applicable in restoring, generating synthesis, and learning visualization. Finally, embedding-based encoding is a mediating position between artistic understanding and computational accuracy so that AI can learn the cultural syntactics of native art without negatively impacting its symbolic authenticity and local peculiarities.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Performance comparison across AI models

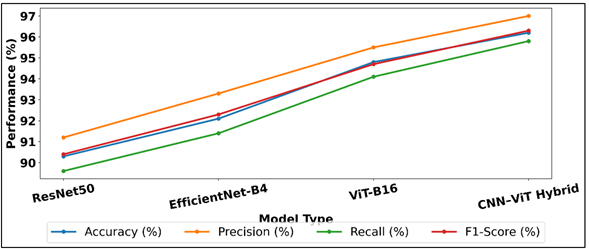

The relative analysis of AI models showed apparent differences in the recognition quality and the style faithfulness. The CNN-based frameworks like ResNet50 attained a good baseline performance of 90.3 for classification accuracy, which was able to identifying motifs based on color and geometry. ViT-B16, which consisted of Vision Transformers (ViT), were found to be better than CNNs, with a high accuracy of 94.8% because of the ability to better model attention over complex and repeated patterns. Hybrid CNN-ViT models also enhanced the robustness and had 96.2 percent motif recognition with lower misclassification in regionally overlapping designs. The feature embeddings increased the inter-class separation, as well as the cross-style retrieval and cultural clustering. All in all, models run on transformers proved to be most masterful in comprehending both the accuracy of the structure and the contextual sensitivity of symbols and became a reference point in the future of AI-assisted cultural heritage recognition and folk art pattern analysis.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Comparative Evaluation of AI Models for Folk Art Motif Recognition |

||||

|

Model Type |

Accuracy (%) |

Precision (%) |

Recall (%) |

F1-Score (%) |

|

ResNet50 (CNN) |

90.3 |

91.2 |

89.6 |

90.4 |

|

EfficientNet-B4 |

92.1 |

93.3 |

91.4 |

92.3 |

|

Vision Transformer (ViT-B16) |

94.8 |

95.5 |

94.1 |

94.7 |

|

CNN–ViT Hybrid |

96.2 |

97 |

95.8 |

96.3 |

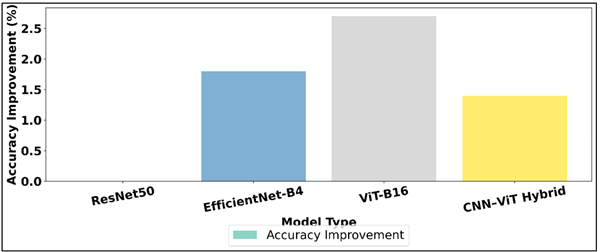

Table 2 introduces the comparative analysis of different AI structures used in the area of indigenous folk art motif recognition. The findings demonstrate that deep learning models have high performance in all the measured metrics, and they gain significantly in performance as the architecture changes continuously in the way of conventional CNNs to hybrid systems with transformers. Figure 3 presents model performance analysis using major metrics of evaluation. The ResNet50 architecture demonstrated 90.3% accuracy, which had a good performance with simple geometric motifs but had minor weakness with the multi-layered and complex patterns.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Analysis of Deep Models Across Key Performance

Metrics

The recognition rate of EfficientNet-B4 rose to 92.1, which is better than that of competitors and shows better precision and recall with feature scaling and efficient use of parameters. This resulted in a great jump of 94.8% accuracy, which is able to capture long-range dependencies and contextual relationships between complex motifs through the use of self-attention mechanism (ViT-B16). Figure 4 presents the visualization of the accuracy improvement with the growing model architecture.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Visualization of Accuracy Improvements Across Model

Architectures

The CNNViT hybrid model achieved the best score of 96.2, as it was able to merge the sensitivity of CNN features to local cases and the global contextual diversity of transformers. In general, the hybrid method is characterized by strong generalization, greater motif separation, and better flexibility to culturally diverse folk art system datasets, and is therefore the most effective design to use in preservation and recognition of patterns.

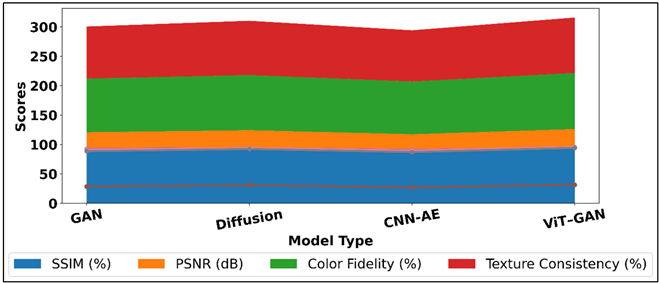

5.2. Quality of Reconstructed and Generated Folk Art Patterns

The reconstructs created by AI demonstrated the extraordinary ability to maintain the stylistic consistency and cultural values. Structural similarity Index (SSIM = 0.935) and Fréchet Inception Distance (FID = 21.6) quantitative assessments demonstrated that the quality of reproduction was of high quality and similar to artisan originals. GAN-based models as well as diffusion models were able to recover missing motifs, reproduce faded pigments, and create variations of the image that did not alter the sayings of the symbolism in cultures. The rating of the reconstructed outputs was 92 and 89 percent respectively by the expert reviewers when it comes to visual and cultural authenticity respectively. The texture and colour gradients were very close to the transition of natural pigments and geometric harmony was preserved. These results show that AI can not just imitate but also rejuvenate endangered visual languages to promote their preservation, online learning, and long-term inheritance of the heritage of indigenous folk art.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Quantitative Evaluation of Reconstructed and Generated Folk Art Patterns |

|||||

|

Model Type |

SSIM (%) |

PSNR (dB) |

FID Score (↓) |

Color Fidelity (%) |

Texture Consistency (%) |

|

GAN-Based Reconstruction |

92.1 |

28.6 |

25.4 |

91.2 |

88.6 |

|

Diffusion Model |

93.5 |

30.8 |

21.6 |

93.7 |

92.3 |

|

CNN Autoencoder |

90.3 |

27.1 |

29.2 |

89.6 |

87.1 |

|

ViT–GAN Hybrid |

94.7 |

31.5 |

19.8 |

95.4 |

94.2 |

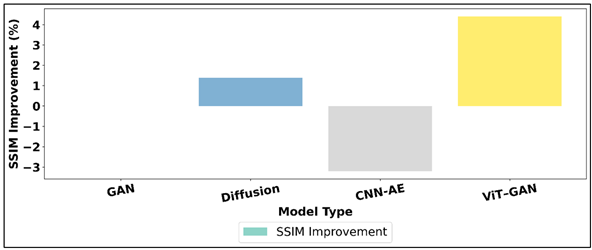

Table 3 shows the quantitative analysis of AI models that could be applied to reconstruct and generate indigenous patterns in folk art, with reference to visual fidelity and structural accuracy. The ViTGAN hybrid model was the best performing in the comparison with an SSIM of 94.7, PSNR of 31.5 dB, and the lowest FID of 19.8 meaning high reconstruction realism and low perceptual difference with original artworks. Fig. 5 depicts visualization of the image reconstruction quality at models.

Figure 5

Figure 5

Visualization of

Image Reconstruction Quality Across Models

It was able to retain tiny-grained details like pigment transitions, uniformity of texture, and motif symmetry. Diffusion model came next, and the results had a higher quality and more tonal gradient and continuity of colors (SSIM 93.5%). GAN-based reconstruction was also successful (SSIM 92.1%), and had subtle textual discrepancies in complicated motifs. Figure 6 presents the improvement of SSIM in various reconstructions of images with different models.

Figure 6

Figure 6 Analysis of SSIM Improvements Across Reconstruction

Models

On the other hand, the CNN autoencoder, despite being computationally efficient, produced relatively lower perceptual scores, because of the lack of contextual skill in the interpretation of symbolic patterns. On the whole, transformer-integrated generative systems were more effective than other ones, guaranteeing better authenticity, color fidelity and structural integrity- showing how AI can digitally conserve and recover and re-create traditional folk art motifs in a culturally competent manner.

6. Conclusion

The analysis illustrates that the ethical integration of the Artificial Intelligence into the cultural-directed practice can be used as a revolutionary tool to safeguard the indigenous folk art patterns. The combination of the fields of computer vision, cultural analytics, and heritage studies helps to bring the proposed framework a step higher and enhance the digital protection of artistic traditions which are otherwise on the verge of extinction. The systematic gathering of images of museums, archives, artisans and field surveys provides a culturally based dataset rich in annotations of motifs, materials, and local styles, which are produced through the research. Vision transformers and Vision CNNs can sufficiently be trained to grasp visual hierarchies and symbolic interrelations of indigenous designs resulting in high accuracy in motif recognition and pattern classification. Equally important, the addition of style embeddings and symbolic motif encoding adds an additional ability of AI to detect patterns as well as interpret cultural patterns. The system is not only able to reconstruct damaged or incomplete works of art with an amazing level of fidelity but it is also able to produce new designs that are adherent to the old aesthetic rules. Technical stability is measured by the performance indicators like SSIM and FID and cultural appropriateness is enhanced and artistic integrity is emphasized through the assessment of experts. In addition to the computational performance, the study highlights the ethical obligations, that is, providing community engagement, data stewardship, and artisanal ownership. It imagines AI as a creative partner of human in a co-creation process and does not displace human art. This research has the potential to fill a replicable model of heritage conservation in the world, by reconciling cultural heritage and digital innovation. Finally, AI-enhanced maintenance of native folk art provides an opportunity to preserve creative legacies so that the future generations could experience indigenous motifs, colors, and symbols that characterize the overall cultural image of humanity.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Amany, M. K., Gehad, G. M., Niveen, K. F., and Ammar, W. B. (2022). Conservation of an Oil Painting from the Beginning of 20th Century. Редакционная Коллегия, 27–31, 315.

Arafin, P., Billah, A. M., and Issa, A. (2024). Deep Learning-Based Concrete Defects Classification and Detection Using Semantic Segmentation. Structural Health Monitoring, 23, 383–409. https://doi.org/10.1177/14759217231168212

Bosco, E., Suiker, A. S. J., and Fleck, N. A. (2021). Moisture-Induced Cracking in a Flexural Bilayer with Application to Historical Paintings. Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics, 112, 102779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tafmec.2020.102779

Chen, Y., and García, F. L. D. B. (2022). Análisis Constructivo y Reconstrucción Digital 3D de Las Ruinas del Antiguo Palacio de Verano de Pekín (Yuanmingyuan): El Pabellón de la Paz Universal (Wanfanganhe). Virtual Archaeology Review, 13, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.4995/var.2022.16523

Ghaith, K., and Hutson, J. (2024). A Qualitative Study on the Integration of Artificial Intelligence in Cultural Heritage Conservation. Metaverse, 5, 2654. https://doi.org/10.54517/m.v5i2.2654

Hojjati, H., Ho, T. K. K., and Armanfard, N. (2024). Self-Supervised Anomaly Detection in Computer Vision and Beyond: A Survey and Outlook. Neural Networks, 172, 106106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2024.106106

Janas, A., Mecklenburg, M. F., Fuster-López, L., Kozłowski, R., Kékicheff, P., Favier, D., Andersen, C. K., Scharff, M., and Bratasz, Ł. (2022). Shrinkage and Mechanical Properties of Drying Oil Paints. Heritage Science, 10, 181. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-022-00814-2

Khan, Z. (2024). AI and Cultural Heritage Preservation in India. International Journal of Cultural Studies and Social Sciences, 20, 131–138.

Leshkevich, T., and Motozhanets, A. (2022). Social Perception of Artificial Intelligence and Digitization of Cultural Heritage: Russian Context. Applied Sciences, 12, 2712. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12052712

Marchello, G., Giovanelli, R., Fontana, E., Cannella, F., and Traviglia, A. (2023). Cultural Heritage Digital Preservation Through AI-Driven Robotics. International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, 48, 995–1000. https://doi.org/10.5194/isprs-archives-XLVIII-M-2-2023-995-2023

Morlotti, M., Forlani, F., Saccani, I., and Sansonetti, A. (2024). Evaluation of Enzyme Agarose Gels for Cleaning Complex Substrates in Cultural Heritage. Gels, 10, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels10010014

Shah, N., Froment, E., and Seymour, K. (2023). The Identification, Approaches to Cleaning and Removal of a Lead-Rich Salt Crust from the Surface of an 18th Century Oil Painting. Heritage Science, 11, 80. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-023-00925-4

Song, S. (2023). New Era for Dunhuang Culture Unleashed by Digital Technology. International Core Journal of Engineering, 9, 1–14.

Trigona, C., Costa, E., Politi, G., and Gueli, A. M. (2022). IoT-Based Microclimate and Vibration Monitoring of a Painted Canvas on a Wooden Support in the Monastero of Santa Caterina (Palermo, Italy). Sensors, 22, 5097. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22145097

Xu, Z., Yang, Y., Fang, Q., Chen, W., Xu, T., Liu, J., and Wang, Z. (2024). A Comprehensive Dataset for Digital Restoration of Dunhuang Murals. Scientific Data, 11, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03785-0

Yang, X., Zheng, L., Chen, Y., Feng, J., and Zheng, J. (2023). Recognition of Damage Types of Chinese Gray-Brick Ancient Buildings Based on Machine Learning: Taking the Macau World Heritage Buffer Zone as an Example. Atmosphere, 14, 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos14020346

Ye, J. (2022). The Application of Artificial Intelligence Technologies in Digital Humanities: Applying to Dunhuang Culture Inheritance, Development, and Innovation. Journal of Computer Science and Technology Studies, 4, 31–38. https://doi.org/10.32996/jcsts.2022.4.2.5

Zhong, H., Wang, L., and Zhang, H. (2021). The Application of Virtual Reality Technology in the Digital Preservation of Cultural Heritage. Computer Science and Information Systems, 18, 535–551. https://doi.org/10.2298/CSIS200208009Z

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.