ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

NṞTYA GAṈAPATI: INSIGHTS FROM LITERATURE, ICONOGRAPHY AND BHARATANATYAM

K. Vadivelou 1![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Saju George 2

,

Dr. Saju George 2![]()

![]()

1 Research

Scholar, Kalai Kaviri College of Fine Arts (Affiliated to Bharatidasan

University), Tiruchirapalli, India

2 Research

Supervisor, Department of Dance, Kalai Kaviri College of Fine Arts (Affiliated

to Bharatidasan University), Tiruchirapalli,

India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

In Hinduism, dance is a

ritual, and deities like Siva and Krishna are depicted as dancers. The Bhakti

period in South India facilitated the development of music and dance as

avenues to praise God and attain salvation or eternal bliss. Lord Siva,

particularly, is revered as the God of dance, and various dancing forms of

other Gods are present in Hindu Mythology alongside Nataraja. Gaṇapati worshipped as the remover of obstacles, is

specifically praised as Nartana Gaṇapati in

his dancing form. The Agamas enumerates sixteen forms of Gaṇapati,

with Nṛtya Gaṇapati,

the dancing form, being one of them. References in Vināyakar

Parākkiramam and numerous literary

works elaborate on different aspects of Gaṇapati's

dance. Presently, Bharatanatyam performances incorporate kritis,

slokas, and songs dedicated to Nartana Gaṇapati.

This form is established and venerated in Siva and Gaṇapati

temples, often depicted through sculptures nationwide. This article delves

into numerous literary references and temple depictions to enhance

comprehension of Gaṇapati as a dancer and the

incorporation of Nṛtya Gaṇapati

in Bharatanatyam. |

|||

|

Received 28 September 2023 Accepted 21 February 2024 Published 28 February 2024 Corresponding Author K. Vadivelou, vadivelou123@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v5.i1.2024.690 Funding: (Ref.

No.15498/Ph.D.K7/Dance/Part-Time/July2014). Copyright: © 2024 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Nṛtya Gaṇapati, Nartana Gaṇapati,

Dancing Gaṇēsa, Bharatanatyam |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

In Hinduism, the ritualistic inclusion of music and dance is inherent in daily practices and special events. Within the Bhakti cult's evolution, these artistic expressions became revered as channels for divine praise and a pathway to salvation. Notably, deities like Siva and Krishna were cast as divine dancers in Bhakti literature. Agamic temples, reflecting diverse deity forms, prominently featured Gaṇapati's worship during the Bhakti period. Dancing Gaṇapati icons abound in temples nationwide, embodying his role as a dancer evident in Puranic literature, epigraphic records, and artistic depictions. Notably, literary works, encompassing slokas and kritis, acknowledge Gaṇapati's dance, with these compositions integrated into contemporary Bharatanatyam performances. This article delves into the eminence and significance of Gaṇapati's dance as illuminated in both literary and artistic realms. Malaiya (1991)

2. Literature review

The portrayal of Dancing Ganapati is a recurring motif examined across diverse literary and artistic traditions. Textual references found in seminal works such as the Vināyakar Parākkiramam and Ganesh Purana, Srī Tattvaniti, Vināyakar Aghaval, underscore Ganapati’s dance as saturated with profound mythological and ritualistic significance. Additionally, compositions by revered Carnatic music compoers like Thyagaraja and Muthuswamy Dikshitar provide nuanced insights into the devotional and aesthetic dimensions inherent in Ganapati’s dance within the musical domain. Furthermore, the enduring presence of sculptural representations in temple art serves as tangible evidence of Dancing Ganapati’s enduring cultural and artistic prominence. Dēsigar (1992)

3. Research Gap

In the existing and explored research on Dancing Ganapati in literature, icons, and Bharatnatyam, there remains a gap in understanding the intricate connections between these domains. Further study is needed to elucidate how literary and iconographic representations of Dancing Ganapati influence the choreography and symbolism in Bharatnatyam performances. Closing this gap will deepen our understanding of the cultural and artistic significance of Dancing Ganapati within Bharatnatyam practice.

4. The legend of Gaṇapati

In Hinduism, Gaṇapati holds significant reverence as a deity, particularly known for his role in overcoming obstacles. In daily temple rituals, Gaṇapati is prioritized, receiving offerings before other deities. Gaṇēsa is visually depicted with an elephant head. Jansen (1993)

The Siva Purana narrates the legend of Gaṇapati. Parvati created a guardian boy whose head was severed by Siva's Trishul. In response to Parvati's plea to restore the boy's life, an elephant head was affixed, bringing him back to life, and he became known as Gaṇapati. The name Gaṇēsa designates him as Gaṇapati in Sanskrit, meaning "Lord of the Hosts," signifying his leadership among demigods and as head of celestial armies.

Gaṇapati is recognized by various names such as Vināyaka, Vigṉeshvara, Eka tantā, Vigṉesha, Vigṉaharta, Vigṉa rājā, Buddi priyā, Gaṇēsa. The name Eka tantā signifies him having a single tusk, with the other tusk sacrificed to scribe the epic Mahabharata. In South India, he is commonly referred to as Pillaiyar, meaning noble child in Tamil. Gaṇapati is also worshipped in Buddhist Tantra. Gaṇapati is praised in thirty-two distinct forms, with Nṛtya Gaṇapati, the dancing form, being one of them. Kolhatkar (2004)

5. Nṛtya Gaṇapati

Gaṇēsa appears in the form of Nṛtya Gaṇapati, considered an emanation from Ōmkāra, the Pranava Mantra Kumaran (n.d.). Gaṇapati possesses the ability to create the illusion of the world's appearance and disappearance. The act of Gaṇēsa's dance receives recognition for its commendation of the inherent rhythm that harmonizes all current manifestations Grimes (1995) .

Nṛtya Gaṇapati is the fifteenth form among the thirty-two forms of Gaṇapati. In this form, he is praised as a Happy Dancer, appearing in a golden complexion with a dancing posture under the Karpaga Vruksham, the celestial tree of boons. In some sculptures, he is depicted dancing with accompanists beneath a mango tree.

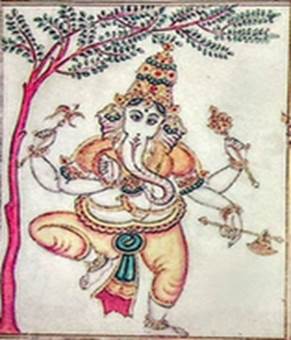

The shloka of Nritya Ganpati in Srī Tattvaniti is,

“Pashankusha Kutaradanta Chanchatkara

Kalupta Varanguleeyakam

Peetamprabham kalpa taror dhashtham bhajami

Nritthopa Padam Gaṇēsam.”

|

Figure 1 Nṛtya Gaṇapati, Srī Tattvaniti Wodeyar (2004) |

Noose, goad, and tusk are the attributes held by Nṛtya Gaṇapati, who appears adorned with rings adorned with glittering gemstones (Figure 1). This manifestation of Gaṇapati is believed to bestow proficiency and success upon devotees, particularly in the realm of fine arts Wodeyar (2004) .

6. Dance of Gaṇapati in

Literature

The Mudgala Purana, Srī Tattvaniti, and Gaṇeśa Purāṇa all make mention of Nṛtya Gaṇapati, depicted as dancing with joy Kumaran (n.d.). The Tamil text, Vināyaka Parākiramam, draws from various Puranas to elaborate on diverse contexts of Gaṇapati's dance. According to the narrative in this text, a demon named Tuntupi attempted to poison the young Gaṇapati with fruits, but Gaṇapati thwarted this threat by decapitating and dancing on Tuntupi's lap, an episode referred to as Tuntupi Marataṉa niṟthaṉa Parākkiramam Banukavi (1908). Another work, Nūppurācura Caṅkāra Parākkiramam, details an episode where Gaṇapati defeats Nupurasura by dancing, resulting in his demise Banukavi (1908). Maccācura Caṅkāra Parākramam narrates sages witnessing Gaṇapati's singing and dancing, while Cāyācura Caṅkāra Parākkiramam highlights Gaṇapati's dance with his brother Karthikeya Banukavi (1908).

The Ganapati Shodasa Nama Stotram in the 24th division of Upasana Khanda of Ganesh Purana, praises the 16 names of Lord Ganesh. The fifteenth stotra praise on Nṛtya Gaṇapati.

Avvaiyār, a prominent Tamil female poet of 8th Century CE Vinayagar Agavalgal. She references Gaṇapati's dance in Vināyakar Aghaval, describing the different sounds produced by his anklets as he dances Vinayagar Agavalgal. Nakeerar, poet of 10th century CE, in his Vināyakar Tiruvaghaval verses, mentions the syllables corresponding to Gaṇapati's dance Pillai (1951). In Civañāṉapōta Vacaṉalaṅkāra Tīpam, a Saiva philosophy text of 19th century, the second invocation song refers to Lord Siva playing the drum Thudi to the dance of Gaṇapati Pillai (1951).

The blissful appearance of Dancing Gaṇapati is noted in the first verse of Gaṇēsa Bhujangam by Adi Shankara of 8th Century CE. Kalpaka Gaṇēsa pañca ratṉam by Umāpati Civāccāriyār refers as “Raṇatk ṣutra kaṇṭāṉi ṉātāpi rāmam calattāndavot tantavatpat matālam…”. The above text also narrates the story of Nṛtya Gaṇapati dancing for the sake of Rishi Durvasa Arunachalam (1971). Atirā aṭikaḷ of 8th Century CE, defines the dance of Gaṇapati in his Child form as, "Nilantuḷaṅka mēru tuḷaṅka neṭuvāṉ nalaṉ tuḷaṅka cappāṇi koṭṭum kalantu uḷam koḷ kāmāri eṉṟa karuṅkaikkaṭattu māmāri īṉṟa maṇi" Arunachalam (1971). Tillaik Kaṟpaga Vināyakar Veṇpāvantāti is a Tamil text of 19th century CE, praising the dancing Gaṇapati of Chidambaram Chettiar (1916) .

7. Dance of Gaṇapati in

Musical Compositions

Oothukkaadu Venkata Kavi's Kriti, "Ānanda nartana Gaṇapatim bhāvayē cidākāra mūlādhāra ōmkāra gajavadanam paramam ..." is a well-known piece often performed in Bharatanatyam concerts. The composer praises the bowing to Gaṇapati, dancing in bliss.

In another kriti, Thyagaraja depicts Gaṇapati's

movement and dance for syllables ‘Tittaḷāṅku’ as in

"Srī Gaṇapatiṉi sēvimparārē

srita māṉavulārā ....tyākarāja viṉutuṭu

vivita katula tittaḷāṅkumaṉi veṭaliṉa..".

This kriti advises to bow to Gaṇapati, who moves dancing to the rhythmic syllables of 'Tittaḷāṅku'.

Muthuswami Dikshitar praises Gaṇapati's fondness for

Drama is referred in "Srī mahā kaṇapatim māṉasa

smarāmi

vaciṣṭa vāmatēvāti vantitā..,Mahākāvyā nāṭakati

piriyam"...

Heramba Murthi, a lyricist, and music composer, has crafted a composition on Nartana Gaṇapati titled “Narttaṉa kaṇapatiyē…” in Hamsadvaṉi raga, Adi Tala Mūrti (1998).

Lalgudi Gopala Iyer, father of violinist Lalgudi Jayaraman, has also composed songs frequently danced in Bharatanatyam, including compositions on Gaṇapati. Keertanams like “Pranava Mudalvane’’ in raga Vacaspati and Rupaka Tala, and “Iniyagilum..” in raga Manirangu and Adi Tala. Additionally, Lalgudi Jayaraman has composed a Thillana on Gaṇēsa in raga Kadanakuthuhalam and Adi Tala Khokar (n.d.).

8. Nrtya Gaṇapati in Icons

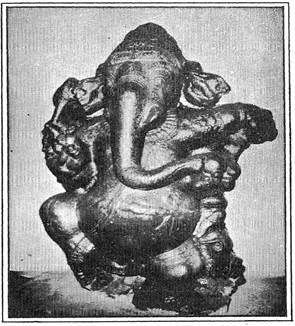

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 Bronze Icon of Nartana Ganpati @ Vedaranyam Sivan Temple Toṇṭaimāṉ (2000). |

In the Vedaranyam Sivan temple, a bronze icon of Nartana Ganpati is present (Figure 2). The Thanjavur Art Gallery houses a granite Nartana Ganpati in the Thanjavur Palace Art Gallery Museum, previously located in the Darasuram Temple Toṇṭaimāṉ (2000) (Figure 3). The Manakula Vinayagar temple in Pondicherry hosts a larger Nartana Gaṇapati bronze icon.

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 Nartana Ganpati @ Thanjavur Palace Art Gallery. Toṇṭaimāṉ (2000) |

Karpaga Vinayagar, in various forms of Ganpati, is the primary deity at the Sri Nataraja Temple in Chidambaram. The Nritya-Ganapathi, housed in a separate temple near the western tower of the Sri Nataraja Temple, is referred to as Karpaga Vinayagar. Toṇṭaimāṉ (1942)

|

Figure 4 Nartana Ganpati @ Gangai Konda Chola Puram |

In Gangai Konda Chola Puram, a Nartana Ganpati is visible on the outer south wall of the Brihadeeswarar Temple (Figure 4). Accompanied by the dance and music of Bhūtaganās, dwarfs playing various musical instruments are depicted in three panels, two on both sides and one beneath the Nartana Gaṇapati. Sivaramamurti (2007) Two additional panels of dancing women are also found under the Nartana Gaṇapati, forming a group.

The foundational sculptural structure of Nṛtya Gaṇapati emerges from the Rajalochana Temple, Rajim. Nṛtya Gaṇapati depiction is notably observed in the KatiSama karana, where Ganpati is portrayed with one hand raised in the Udvahita Katti pose. In numerous cultural representations across India from the 13th to the 15th century CE, dancing Ganpati is often depicted with one foot in the kunchita position, with the raised heel, while the other foot remains on ground. This pose, termed Lalita karna, features the right hand in vivarita mudra and the left hand in karihasta mudra Malaiya (1991). Dancing Gaṇapati is commonly seen in temples across North Indian states such as West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Orissa, and Karnataka, belonging to the period of 9th to 12th century CE.Various poses of Nṛtya-Gaṇapati, with a variety of Sthānaka bheda, are observed.

From the Chola period, 9th century CE, Sivan temples of Tamil Nadu have Nartana Gaṇapati icons. In these temples, Dancing Gaṇapati is placed just before the Palipīṭam and on the front board of the Koṭimaram, the flagpole at the entrance of Sivan Temples. Gaṇapati is also positioned on the south side of the Arda Mandapam, the outer wall of the Sanctum in Sivan Temples. Nartana Gaṇapati is present in a separate small temple in the prākāram in Sivan Temples like Chidambaram, Mylapore, Vaideeswaran Koil, Thiruthurayur, Madurai, Thirukkodikaval.

9. Dance Of Gaṇapati in

Bharatanatyam

In Bharatanatyam, dancers embody Gaṇēsa with the Kapita hasta in both hands, where the right hand faces up, and the left hand faces down (Figure 5). Both hands are positioned away from the body, and the right foot in Ancita pada has toes raised with heels resting on the ground. This hand position is a part of Dēvata hasta, as described in the Abhinaya Darpana of Nandikesvara.

Figure 5

|

Figure 5 Sankar (2016). Bharatanatyam Dancers. Pondicherry.Sri. Krishnan and Smt. Preetha Posing Gaṇēsa. Copyright@ Puduvai Bharathalaya |

Typically, a Gaṇēsa Stuti or Kauthuvam is performed at the beginning of a Bharatanatyam performance. Dancer V. P. Dhananjayan composed and choreographed a Padavarnam on Pillaiyar or Gaṇēsa titled ‘Vinayaka Varnam,’ set in Nattakurinji raga. This varnam was performed as part of a Gaṇēsa temple consecration in 1982. Dancer Sudharani Raghupathy and her student Aruna Subbaiah created a Margam format devoted to Gaṇēsa and Muruga. Included in this format is the Padavarnam on Gaṇēsa, ‘Om enum porule’ in Hamsadhwani raga and Adi tala. Choreographed by Sudharani Raghupathy, it explores the legends related to Vinayaka. Dancer Krishna Kumari Narendran choreographed group productions on Gaṇēsa in Bharatanatyam, namely Sri Maha Ganapathi and Sodasha Ganapathi. Jayanthi Raman, a US-based dancer, choreographed a dance drama called Gajamukha during a US tour, involving three classical dance styles, including Bharatanatyam Khokar (n.d.). Dancers adopt Nṛtya Gaṇapati by emulating and posing on Gaṇapati in dance pieces. An understanding of the significance of Gaṇapati as a dancing lord is provided by these presentations of Nṛtya Gaṇapati in dance performances by renowned choreographers and senior Gurus.

In Yagasala rituals during temple consecrations, priests recite Gaṇapati Tala to the music of Nadaswaram and Thavil. In a few places in the Kongu region of Tamil Nadu, priests adorned as Gaṇapati dance to Gaṇapati Tala accompanied by music.

In the portrayal of Nṛtya Ganapati, the literature, and the icons on Nṛtya Ganapati, are the sources to adopt in dance. The dancing form of Lord Ganapati, his divine grace and joy are expressed through intricate dance movements. Through dance performances in his praise, audience experience the vibrant energy and auspiciousness embodied by Nṛtya Ganapati, fostering a deeper connection with the divine.

10. Conclusion

In the intricate tapestry of Hindu artistic and spiritual traditions, Nṛtya Gaṇapati emerges as a sublime manifestation, embodying profound cosmic significance akin to Shiva's celestial dance. Rooted in Hindu Mythology, Gaṇapati's dance encapsulates the cyclical rhythm of creation and dissolution, embodying a metaphysical force shaping the fabric of existence. The sacred dance, intricately associated with the Kalpavriksha tree, signifies the granter of wishes and blessings, invoking deep spiritual resonance. In the performing arts, dancers ritualistically invoke Gaṇēsa, especially in Bharathanatyam concerts. Nṛtya Gaṇapati as thematic richness found in foundational texts like Vināyaka Parākiramam, intricately weave tales of triumph over adversity, the pursuit of joy, and the conferral of divine blessings, reflecting nuanced layers of Hindu devotional literature.

Dancing Ganapati icons in temples symbolize the cosmic dance of creation and destruction, reflecting the universe's intricate rhythms with artistic significance. In these sacred spaces, devotees connect spiritually through the profound language of dance, music, and symbolic art. Musical compositions dedicated to Nṛtya Gaṇapati, spanning Kritis, Pada Varnam, and Thillana, seamlessly integrate into Bharatanatyam, perpetuating a rich cultural legacy. This exploration underscores the symbiotic relationship between literature, iconography, and dance, providing profound insights into the spiritual and artistic dimensions converging in the divine dance of this revered deity.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Arunachalam, M. (1971). Tamil Ilakkiya Varalaru, Pathinoram Nutrandu. Chennai: Pari Nilayam.

Avvaiyar, V. A. (1958). Chennai: Sri Kamakoti Kosthanam.

Banukavi, M.T. (1908). Vināyaka Parākiramam. Chennai: Rubi Press.

Chettiar, C. (1916). Tillaik Kaṟpaga Vināyakar Veṇpāvantāti. Saiva Vithyānupālaṉa Yantiracālai.

Dēsigar, D. (1992). Gaṇapati. Tiruvāvaduduṟai Adheenam.

Grimes, J. A. (1995). Gaṇapati: Song of the Self. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Jansen, E. R. (1993). The Book of Hindu Imagery: Gods, Manifestations and Their Meaning. Binkey Publications.

Khokar, A. (n.d.). The Concept of Gaṇēsa in Dance.

Kolhatkar, M. (2004). Review: Gaṇeśa, Lord of Obstacles, Lord of Beginnings. Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, 85, 186-189.

Kumaran, T. S. (n.d.). Gaṇēsa.

Malaiya, S. (1991). Nritta Gaṇapati in India and Beyond its Frontiers: Summary. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 52, 1059-1061.

Mūrti, H. (1998). Kīrttaṉa Mālai- Vol 3. Yāḻppāṇam: Srī Subramaṇiya Accakam.

Pillai, M. S. (1951). Vinayagar Agaval. Tiruvāvaduduṟai Adheenam.

Sivaramamurti, C. (2007). The Great Chola Temples. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India.

Toṇṭaimāṉ, B. (1942). Vinayagar Agavalgal. Dharmapuram: Dharmapuram Adheenam.

Toṇṭaimāṉ, B. (2000). Piḷḷaiyārpaṭṭi Piḷḷaiyār. Bāskara Nilayam.

Wodeyar, S. M. K. R. (2004). Sritatvnidhi- Sivanidhi Volume 3. Dr. K.V. Ramesh (Ed.). Mysore: Oriental Research Institute.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.