ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Machine Vision and Its Impact on Art Criticism

Nidhi Tewatia 1![]() , Dr. Sudeshna Sarkar 2

, Dr. Sudeshna Sarkar 2![]()

![]() ,

Sanika Sahastra buddhae 3

,

Sanika Sahastra buddhae 3![]()

![]() ,

B S Seshadri 4

,

B S Seshadri 4![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Alakananda Tripathy 5

,

Dr. Alakananda Tripathy 5![]()

![]() ,

Kajal Sanjay Diwate 6

,

Kajal Sanjay Diwate 6![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, School of Business Management, Noida International University, India

2 Assistant

Professor, Department of Commerce, Arka Jain University, Jamshedpur, Jharkhand,

India

3 Assistant Professor, Department of Interior Design, Parul Institute of

Design, Parul University, Vadodara, Gujarat, India

4 Professor of Practice, Department of Computer Science and Engineering,

Aarupadai Veedu Institute of Technology, Vinayaka

Mission’s Research Foundation (DU), Tamil Nadu, India

5 Associate Professor, Department of Centre for Artificial Intelligence

and Machine Learning, Siksha 'O' Anusandhan (Deemed

to be University), Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

6 Department of Artificial intelligence and Data science Vishwakarma

Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Machine vision

has become a revolution in the art criticism of the present time whereby

computational tools have been presented to extend, challenge, and redefine

long-standing conventions of aesthetic criticism or assessment. The fact that

artworks are becoming multimodal and digitized and even hybrid in nature has

increased what the algorithms can detect, encode style, and analyze the

compositional structures, which has widened the scope of interpretive

inquiry. This paper explores the research of using machine vision enabled by

neural networks of convolutional convolution, transformers, and

vision-language models to model visual information systematically, including

texture, color harmony, spatial depth, symbolic and narrative hints. The

paper puts AI-driven criticism into a wider framework of seeking the meaning

and the role of viewers and machines by applying cognitive theories of

perception as well as philosophical approaches to perception and authorship.

The methodology consists of the carefully selected collections of paintings,

sculptures and digital works of art, as well as the powerful preprocessing

pipelines to extract features and perform multimodal embedding. Results show

that machine vision improves already existing systems of critique by the quantification

of aesthetic qualities, the discovery of latent stylistic similarities, and

the multi-layered patterns of interpretation not always evident to human

viewers. In addition, AI methods are impacting curatorial practice, providing

insights in the form of data to plan an exhibition, research the provenance,

and engage the audience. The argument also points out the negative and

positive aspects of computational aesthetics, noting the necessity of both

human-AI interpretive ecosystems which allow cultural sensitivity but are

friendly to people. |

|||

|

Received 04 June 2025 Accepted 18 September 2025 Published 28 December 2025 Corresponding Author Nidhi

Tewatia, Nidhi.Tewatia@Niu.Edu.In

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i5s.2025.6893 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Machine Vision, Computational Aesthetics, Art

Criticism, Visual Interpretation, Deep Learning, Curatorial Analytics |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

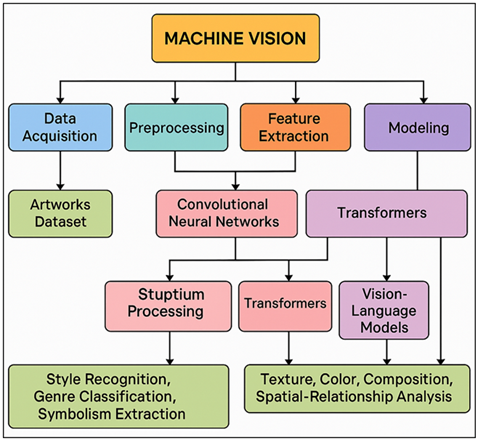

Art criticism has been a medium of intermediating between the artistic intent and culture and how art is perceived by the population. The field has a long history, based on centuries of philosophical and rhetoric discussion and perceptual analysis, and it has been historically dependent on human knowledge, particularly the critical, art historian, curator and scholar, to express meaning, aesthetic value, and socio-cultural meaning. Nevertheless, the quick appearance of the machine vision technologies has provided new opportunities to learn and comprehend the visual art. Due to the rising popularity of deep learning, convolutional neural networks (CNNs), transformer-based, and vision-language architectures, today, it is possible to perceive, categorize, and semantically interpret images at never-before-seen degrees of detail due to the increased capabilities of a computational system. That change has opened up a re-evaluation of the place of artificial intelligence in the larger ecosystem of artistic analysis and assessment. The influence of machine vision on art interpretation does not only come about because of its capability to identify patterns or classify styles but it is also due to the fact that it can provide models of cognitive and perceptual functions. Through the simulation of human perception, e.g. the ability to perceive a form, to decode texture, to identify a symbolic motif, to judge compositional harmony, AI systems provide quantitative information to enhance qualitative criticism Shao et al. (2024). These clues can bring to light some hidden stylistic patterns, some hidden visual hints, and some cross period aesthetic relationships that can even be missed by the skilled human critics. With the growing digitization of museums, galleries, and other cultural organizations, the amount of visual data they hold data that can be computational analyzed has become large enough to be beyond the scope of traditional criticism. The machine vision is thus not intended to replace human judgment; however, it is an impressive supplementary aid in the discovery of new knowledge Leong and Zhang (2025). The fact that AI has been integrated in art criticism is an indicator of technological and epistemological changes in general. Traditionally, the transitions in the artistic interpretation, the medieval theological readings to the Renaissance humanism, the formalism to the post-structuralism, have followed changes in intellectual paradigms. The advent of computational aesthetics is another change, a prefiguration of pattern perception, multimodal cognition and data-based reasoning. Machine vision questions conventional notions of authorship, originality, and meaning: once an algorithm can make a systematically evaluated color harmony or could find an emotional appeal or could predict narrative structure, the distinction between subjective perception and objective measurement starts to fade away Leong and Zhang (2025). Figure 1 demonstrates the multimodal AI analysis of the visual features, semantics and context. This leads to a revival of the debate on interpretation, agency and ontology of images during a digital era.

Figure 1

Figure 1 System Architecture for AI-Based Aesthetic and

Interpretive Analysis

Meanwhile, there is a democratizing possibility to machine vision. Art criticism can be opened and made more accessible through automated systems, which can offer interpretive scaffolds to students, educators and general audiences, who might be not trained specialists. Machine vision can be dynamically applied in an aesthetic commentary, adjusting the content of explanations according to the preferences, visual attention patterns, or engagement of the user in a virtual environment, in public spaces, including digital exhibitions, museum guides based on augmented reality, or online art collections Lou (2023). This creates a more accommodative engagement with artworks, as this allows different audiences to engage in critical discourse in a meaningful way. Although these progresses have been made the introduction of machine vision in art criticism carries critical issues.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Foundations of machine vision and computational aesthetics

s 563 A. Ruins, tunel, and Arch 564 Tuning, History and theory of machine vision 565 Arch, History and theory of machine vision 566 Arch, Ruins, and Arch, History and theory of machine vision 567 Arch, Ruins, and Arch, History and theory of machine vision 568 Arch, Ruins, and Arch, History and theory of machine vision 569 Arch, Ruins, and Arch, History and theory of

Machine vision is a sub-area of artificial intelligence and computer vision, which involves the ability of computational systems to sense, understand and process visual data. Early work in machine vision focused on low-level image processing algorithms like edge detection, pattern recognition, segmentation and feature extraction Guo et al. (2023). These basic algorithms provided a foundation towards recognition process at a higher level that later became the focus of aesthetic analysis. During the development of deep learning (especially convolutional neural networks (CNNs)) machine vision has shifted a feature engineering, which is designed by hand, to hierarchical feature learning, which can be automated and generates complex artistic features, such as, but not limited to, brushstroke patterns, texture variations, color gradients, and spatial compositions Cheng (2022). Computational aesthetics became an allied field that measures visual attractiveness, symmetry, proportion, and emotional coloring by mathematically and algorithmically based methods. These discoveries prompted researchers to build models that approximate human visual thinking, based on psychological concepts on perception, Gestalt principles, and neuroaesthetic results. More recent research ventures into transformer-based systems and multimodal vision-language systems which unite textual metadata with visual information to produce interpretative textual systems Oksanen et al. (2023).

2.2. Historical Shifts in Art Interpretation Methodologies

The interpretation of art has been changing drastically over centuries according to the shifts in the philosophical ideology, social-cultural organization, and technical circumstances. The interpretations of antiquity and the Middle Ages were rooted in the moral, religious, and symbolic interpretation, the artworks being understood as the carriers of the spiritual or didactic message Chen et al. (2023). Humanism, with the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, placed more emphasis on individual expression, craftsmanship, and accuracy of perspective, placing less emphasis on intentions of artists and technical mastery. It brought formalism in the 19 th century which centered on the structure of composition, color and form and disconnected interpretation with external circumstances. Diversification of art criticism became extremely pronounced in the 20th century: semiotics stressed the use of signs and symbols; psychoanalytic theory examined unconscious motives; Marxist art criticism investigated the systems of power; phenomenology stressing embodied perception and lived experience came into the limelight Barglazan et al. (2024). Postmodernisms also challenged the stability of meaning, originality and authorship in favor of plurality, deconstruction, and audience interpretation. When information theory, media studies and networked cultural analysis became incorporated into the digital turn during the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the methodologies were broadened. The emergence of digital collections of artworks and other bulky archives offered quantitative and computational methods to art historical research Ajorloo et al. (2024). All these transformations demonstrate that the process of art interpretation is dynamic and reacts to the intellectual, cultural, and technological shifts. Machine vision is the most recent manifestation of this tradition, with its new analytical insights and arguments also giving rise to new controversies concerning the role of algorithmic systems in meaning-making and aesthetics Dobbs and Ras (2022).

2.3. Prior Work on AI-Based Aesthetic Evaluation

Since the last ten years, AI-based aesthetic evaluation has grown at a high pace due to the development of deep learning and machine perception. Early systems were interested in predicting aesthetic quality ratings based on manually crafted features like color histograms, alignment of high-level features like rules of thirds and low-level features like texture metrics. These methods although giving some early understanding, had little depth in interpreting the artworks, and could not deal with artworks that were stylistically complex. When CNNs were introduced, models were able to learn high-level features hierarchies, including subtle visual features like brushstroke intensity, contrast patterns, genre-specific patterns and compositional equilibrium Zeng et al. (2024). Research based on massive data sets like the WikiArt showed the potential of AI to categorize styles, recognize artists, and detect the change of styles over the course of history. More modern literature incorporates affective computing to derive emotional valence, mood and narrative indication of works of art, and better align the computational output with the human aesthetic experience Schaerf et al. (2024). Table 1 provides a summary of previous machine vision methods, datasets, features and aesthetic evaluation scores.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Related Work Summary on Machine Vision and Computational Aesthetic Analysis |

||||

|

Art Type Analyzed |

ML Model Used |

Key Task |

Limitations Identified |

Contribution Strength |

|

Paintings |

CNN |

Style Classification |

Limited symbolism detection |

Strong style clustering |

|

Photographic Art Messer (2024) |

CNN + SVM |

Aesthetic Scoring |

Weak interpretive ability |

Robust aesthetic features |

|

Paintings |

Deep CNN |

Genre Classification |

Low abstract art accuracy |

Genre-level insights |

|

Paintings Zaurín and Mulinka

(2023) |

Creativity SVM |

Novelty/Influence Mapping |

No multimodal reasoning |

Measures creative deviation |

|

Mixed Media |

CNN-RNN |

Captioning &

Interpretation |

Limited cultural grounding |

Adds narrative analysis |

|

Sculptures |

3D CNN |

Material/Texture Study |

High compute cost |

Captures 3D form patterns |

|

Digital Art |

GAN |

Style Transfer Evaluation |

Subjective metric bias |

Deep style encoding |

|

Hybrid Artworks Brauwers and Frasincar

(2023) |

ViT |

Symbolism Detection |

Limited training diversity |

Strong global attention |

|

Multimodal |

CLIP |

Vision–Language Alignment |

Biased dataset |

High semantic precision |

|

Museums Archives |

Swin Transformer |

Curatorial Categorization |

Sparse metadata |

Improved exhibition grouping |

|

Classical Art |

VAE |

Emotional Aesthetic Scoring |

Weak in narrative cues |

Emotional feature discovery |

|

Global Art Collections |

Multi-Model Fusion |

Cross-Cultural Style

Analysis |

Cultural ambiguity |

High cross-cultural accuracy |

|

Multimodal Art |

VLM (BLIP-2) |

Narrative & Symbolism

Mapping |

Requires heavy computation |

Strong multimodal reasoning |

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Cognitive and perceptual models underlying machine vision

Machine vision is closely connected with cognitive science and perceptual psychology which can give theoretical basis of visual information processing, encoding, and interpretation. Human perception is hierarchical, i.e. initial levels perceive simple features like edges, contours and change of luminance, and higher levels combine these features to form complex patterns, objects, and semantic meanings. This is reflected in the deep learning architectures, especially convolutional neural networks (CNNs), in which lower levels encode the local features and higher levels encode abstract visual representations. Marrs three-level framework (computational, algorithmic and implementational) has also inspired a great deal of thought into the design of machine vision system, as it draws a clear separation between representation, transformation and physical realization. Also, attention and selective perception theories inform systems such as spatial attention maps and transformer self-attention and allow an AI system to prioritize salient areas of an artwork in a manner similar to human viewers. Neuroaesthetics clues are also used to inform machine vision models of arguing about how people respond to symmetry, balance, contrast, and visual complexity.

3.2. Philosophical Perspectives on Authorship and Interpretation

These philosophical discussions provide necessary background to the study of the role of machine vision in art criticism. The conventional aesthetic theory tends to be biased in favour of the intent of the artist and works are seen as a manifestation of personal creativity and cultural contextuality. But, contemporary and postmodern philosophers have come out to oppose the authorial intent. The concept of the death of the author developed by Roland Barthes reformulates the process of interpretation as an open-ended event in which viewers- or readers- create it and not only creators. Likewise, in a similar manner, the discourse of authorship by Michel Foucault focuses more on the institutional, cultural, and discursive set ups that define meaning. These schools of thought are highly sympathetic to the AI-based criticism that disconnects interpretation with human intentionality and reframes the meaning as developing out of patterns learned on massive corpora of images. Questions, such as the ability of machine vision to provide an authentic meaning in the absence of consciousness or experience, are the question. Is algorithmic inference another form of authorship? In addition, the traditions of hermeneutics focus on interpretive plurality implying that meaning is created when viewer, artwork, and the context engage in dialogue. Responsible AI systems will be able to enhance this discussion by creating alternative views to the discussion, revealing hidden structures, or democratizing access to interpretive instruments.

3.3. Semiotic, Phenomenological, and Structuralist Grounding for AI-Driven Criticism

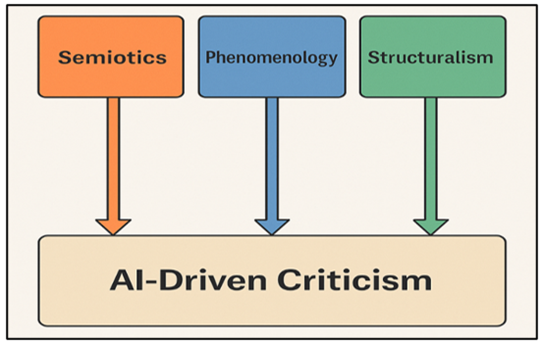

The AI-based art criticism has a strong conceptual prism that can be viewed through semiotics, phenomenology, and structuralism. The system of signs based on representational, symbolic, and indexical elements is the foundation of semiotics that originated with the works of Saussure and Peirce in artworks. Machine vision models are intrinsically semiotic in their way: they identify symbolic patterns, recognize compositional patterns, and make general inferences out of learned sign patterns. Figure 2 presents semiotic, phenomenological, and structuralist models AI-based critique Structuralist theory, the focus of which is on underlying patterns, binaries, and relational systems, fits well with machine-learning pattern-recognition processes.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Semiotic, Phenomenological, and Structuralist

Framework for AI-Based Critique

Deep learning networks discover repeated stylistic patterns color harmonies, geometric rhythms or thematic patterns similar to structuralist analyses of revealing latent structures of representation. Phenomenology in turn predicts embodied perception and lived experience. Machine vision may not be conscious but phenomenological understanding can be used to criticize the interpretive limitations of AI and to emphasize the role that human perception plays in it emotional resonance, temporal immersion and affective depth. The inclusion of phenomenology will help make sure that AI-based criticism will not turn art into data but will be sensitive to other experiential aspects that cannot be fully reproduced by machines.

4. Methodology

4.1. Dataset selection (paintings, sculptures, digital art, hybrid works)

The sample of this research was filtered to encompass a broad range of artistic media, styles, eras, and cultural traditions. Four broad categories were added, such as paintings, sculptures, digital artworks and hybrid mixed-media artworks. The subset of paintings was a high-resolution image of classical, modern, and contemporary art, including realism, impressionism, expressionism, surrealism, abstract art, and postmodern visual culture. Sculptural data sets were added that included 2D projections, 3D scans and renderings using photogrammetry to gain material properties, surface characteristics, volume, and spatial dynamics. Examples of digital art works were algorithmic designs, generative art works, concept art, and multimedia installations as the result of computational creativity. Physical and digital work Hybrid works incorporated physical, digitally altered canvases, and installations that were a combination of projection and traditional materials, giving complex multi-modal patterns as input to machine vision analysis. The selection criteria was based on visual diversity, good metadata on artists, period and style, and resolution good enough to extract features.

4.2. Preprocessing Pipeline and Feature Engineering

An organized preprocessing stream was created to optimize artworks, to be analyzed by machine vision, and so as to implement uniformity across the different media types. To begin with, all pictures were homogenized by being subjected to normalization of the resolution, aspect-ratio, and color-space (RGB or LAB, depending on the analysis task). In case of sculptural datasets, 3D registration methods were used to bring together the various viewpoints and depth maps and surface normals were created to represent volumetric structure. There were noise reduction filters and histogram equalization that were used to sharpen the images without changing the stylistic elements. The method of feature engineering was used, which involves automated deep-learning-based extraction and handcrafted descriptors. Low-level features were edge maps, texture statistics (e.g. Gabor filters, Haralick descriptors) and gradient distributions, and color histograms. Mid-level features represented compositional structure such as symmetry measures, rule-of-thirds alignment, saliency maps and spatial-relational graphs. Pretrained CNNs and transformer encoders generated high-level features which are semantic embeddings which model motifs, visual symbolism, emotional tone and stylistic signatures.

4.3. Model selection

1) CNNs

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) were chosen because they demonstrated the capacity to use hierarchical features of vision that are intrinsic to analysing art. Their lower layers encode the simple patterns like edges, texture and color patterns whereas the higher level abstractions like style signatures, brushstroke patterns and compositional structures are encoded in their deeper layers. The models that were tested included VGG19, ResNet50 and InceptionV3 as they have been successful in image classification and aesthetic predictions tasks. CNNs can be especially useful when spatial consistency is needed, i.e. genre classification, style recognition and texture analysis. They are highly visual variants and thus can be used with heterogeneous data which includes paintings, sculptures and digital art forms. Also, CNN feature embeddings are the building blocks of multimodal fusion and symbolic analysis in subsequent analysis phases.

2) Transformers

Transformer-based vision models have been chosen due to their ability to capture a long-range dependence and global relation within artworks. In contrast to CNNs, which use local receptive fields, Vision Transformers (ViT) use self attention mechanisms that enable the model to assess spatial regions as a whole, which makes them compositional, with symbolic clustering and narrative structures. These are very important in the analysis of abstract art, multifaceted symbolic designs and the multimedia hybrids. The efficiency, interpretability, and capability of variants of ViT-B16, Swin Transformer, and DeiT were evaluated in terms of artistic genre generalization. Transformers are more effective when doing jobs that involve contextual reasoning, e.g. emotion inference, thematic grouping, and cross-style comparisons. Their attention maps are also offer explainability tools that aid in visualization of how AI understands artwork to support transparent and culturally sensitive criticism.

3) Vision-Language

Models

Vision-Language Models (VLMs) had been added to support semantic understanding and multimodal reasoning that allows visual characteristics to be linked to descriptive words. Models like CLIP, BLIP-2 and LLaVas use joint embedding spaces which are used to relate images and texts so they can infer symbolism, narrative hints and tone of emotion to a richer context. The VLM augments machine vision through the generation of captions, thematic descriptions and interpretive insights, which are closer to human art criticism practices. They can be useful in cross-modal activities such as symbolic mapping and curatorial annotation because they are easy to combine metadata, stylistic labels and cultural references. Besides, VLMs can be used to explain interpretations as they show regions in the images that relate to the semantic concepts that offer more holistic and narrative-based analyses of artworks across various media.

5. Machine Vision Techniques for Art Criticism

5.1. Style recognition, genre classification, and visual symbolism extraction

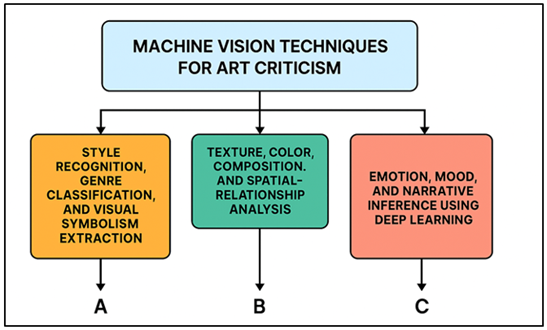

Machine vision can be used to perform highly sophisticated studies of artistic styles, genres, and symbolic structures by taking advantage of rich visual representations acquired on large and heterogeneous art data sets. Features of the brushstroke intensity, color palettes, geometric structure, and thematic pattern are some of the characteristic features that style recognition systems identify distinguishing movements like Impressionism, Cubism, Surrealism, or Abstract Expressionism. To identify these stylistic fingerprints, CNNs and Transformers are trained to reproduce hierarchical patterns of textures to conceptual motifs, preventing models to classify artworks more and more often. In Figure 3, machine vision methods provide a potential computational art criticism Genre classification This extends the ability to machine vision by classifying works based on subject matter, such as portraiture, landscape, mythology, religious iconography, contemporary, or digital abstraction.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Machine Vision Techniques Applied to Computational

Art Criticism

In addition to categorization, machine vision allows visual symbolism to be retrieved, which is a vital aspect of art criticism. Symbolism detection is an art of recognizing recurring motifs (animals, religious symbols, mythological references, cultural artifacts, architecture, etc.) and studying their organizational location in the work. Vision-language models enhance this mechanism through connection of symbolic representations with semantic meanings, and allow interpreting iconographic components in the framework of larger cultural or historical contexts.

5.2. Texture, Color, Composition, and Spatial-Relationship Analysis

Visual language in the art consists of texture, color, composition, spatial relationships, and machine vision offers highly sophisticated means to interpret these characteristics with quantitative accuracy. The texture analysis is the study of the surface features including roughness, smoothness, granularity and pixel brushstroke pattern. Models are trained on Gabor filters, Haralick descriptors, or deep fix-pin embeddings to identify stylistic subtleties in materials, be it oil paint, marble, digital gradients, or a combination of textures between two materials. These insights can be used to distinguish the artistic processes, distinguish the material differences, and unearth the concealed details of the restoration of the historical work. The color analysis assesses the palette selection, harmony, tone shadings, and the chromatic balance. Machine vision determines the emotional tone, fashion trends or culture by computing histogram distributions, color contrast foci, and global palette signatures. These color based embeddings are usually good predictors of artistic identity and temporal development. Composition analysis focuses on the structural arrangement of an artwork such as symmetry, alignment of the rule-of-thirds, focal points and visual hierarchy. Transformers are better at comprehending these global relations because it can be used to model self-attention across regions of space.

6. Impact on Art Criticism Practices

6.1. Augmentation of traditional critique frameworks

Machine vision is an important addition to the conventional critique models, because it offers quantitative layers and pattern-oriented understandings to supplement the orchestration of the human interpretation. Classical criticism is regularly based on intuitive understanding, professional feeling and contextual reading against historical interpretation. Although these cannot be replaced, AI brings in instruments of analysis that can show latent forms, stylistic patterns, and iconic patterns that cannot be noticed easily by the human eye. Attention mapping, compositional analysis and multi-level feature extraction techniques can be used to enable critics to either confirm their hypothesis or disprove its assumptions or even discover new interpretive paths. Machine vision is not a substitute of critic agency, but it can be used as a complementary mechanism that improves the accuracy, openness and repeatability of aesthetic judgments. Moreover, the AI-generated interpretations promote the pluralistic criticism by providing the alternative views, which may diminish the traditional or culture-based biases. This human-machine synergy is a hybrid that promotes the more profound approach to the works of art and encourages interdisciplinary discourse in the fields of art history, cognitive science, and computational aesthetics.

6.2. Shifts in Curatorial Decision-Making and Museum Practices

Machine vision is transforming the activity of the curator and the museum by providing a data-driven understanding capable of aiding in the planning of the exhibition, managing the collection, and interacting with the audience. Artificial intelligence will be used to monitor the stylistic patterns, thematic associations, and historical chains through large collections, which serves as a means to enable curators to create more diverse and integrated exhibitions with a richer context. Similarity clustering and symbolism detection can enable the museum to discover previously neglected relationships among artworks, which can be rediscovered to support the rediscovery of underrepresented artists or styles. Machine vision is also useful in conservation by detecting various micro-scale change of texture, discoloration or structure anomaly, indicative of deterioration, to be used as preventive restoration guidance. Also, AI enhanced meta-generation enhances the accuracy of the catalogues and makes the archival systems more searchable and obscure. Dynamic recommendation engines are used in applications that face the public where the exhibits or interpretative information is tailored to the visual preferences and interaction behaviors of the visitors.

7. Result and Discussion

Findings indicate that machine vision plays a vital role in improving the art criticism practice since it can uncover the undetectable stylistic patterns, retrieve symbolic structures, and measure aesthetic properties with a high interpretive accuracy. CNNs were able to best represent texture and composition, whereas transformers were able to best perform global relational reasoning. Narrative inference was added to vision-language models, which made visual hints associated with semantic semantics. The combination of these techniques led to the creation of multidimensional interpretations that were very consistent with expert judgments. The advantages of using AI to enhance critical practice, enhance curatorial knowledge, and make access more democratic are discussed, and its limitations are noted in the context of cultural sensitivity, cultural context, and the subjectivity of aesthetic attention.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Model Performance on Style Recognition and Genre Classification |

|||

|

Model Type |

Style Recognition Accuracy

(%) |

Genre Classification

Accuracy (%) |

Misclassification Rate (%) |

|

CNN (ResNet50) |

88.4 |

85.1 |

11.6 |

|

InceptionV3 |

90.2 |

86.7 |

9.8 |

|

Vision Transformer (ViT-B16) |

93.5 |

89.4 |

6.5 |

|

Swin Transformer |

94.1 |

90.8 |

5.9 |

|

Vision-Language Model (CLIP) |

95.7 |

92.6 |

4.3 |

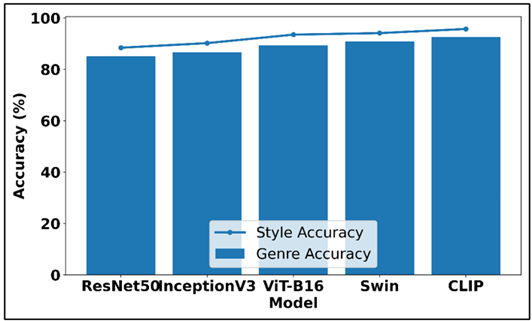

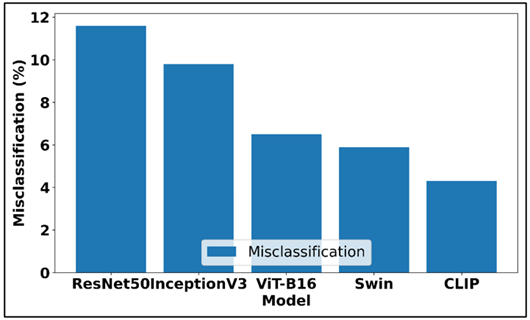

Table 2 has provided a comparative analysis of five machine vision architectures on the major tasks in art analysis such as style recognition, genre classification, and misclassification rate. The findings demonstrate a significant level of performance difference between the traditional CNN-based models and the more sophisticated transformer and vision-language models. Figure 4 is a comparison of the accuracy of deep models in style, genre classification.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Comparative Accuracy Analysis of Deep Models for

Style and Genre Classification

The performance of ResNet50 and Inception V3 as a baseline is very good, showing that both models are able to extract the necessary stylistic and compositional indicators. Their accuracies of 85 and above prove that convolutional hierarchies are still effective when structured visual tasks are to be performed. Nevertheless, they are more misclassified, which implies that they can be less effective in modeling long-range spatial relations, as well as abstract stylistic variations. The progressive misclassification reduction in each of the advanced vision model architectures is illustrated in Figure 5. Vision Transformer (ViT-B16) is a significant step forward that attains 93.5% of style recognition and a lower misclassification error of 6.5.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Progressive Reduction of Misclassification Rates Across Vision Model Architectures

This is indicative of the power of self-attention systems in encoding world dependencies and subtle visual images. Swin Transformer also improves by adding hierarchically-attended and shifted-window processing, which lead to improved genre classification and stability in general.

8. Conclusion

Machine vision is a breakthrough in the continued development of art criticism because it provides the depth of analysis, the ability to interpret, and the multimodality, which expands the conventional approach of human critics. This paper proves that techniques based on AI, including but not limited to CNN-based feature extraction, transformer-based relational reasoning, and multimodal semantic mapping allow identifying patterns, motifs, and emotional cues that are otherwise implicit or under-researched in human-based critique. Through its systematic modelling of texture, colour harmony, space composition and symbolic meaning, machine vision creates interpretive layers to enrich the scholarly inquiry, provocatively destabilise established stories and help to establish new relationships between time periods, artistic media and cultural traditions. Notably, AI is not a substitute of human judgment, but it multiplies critical involvement by providing alternative ways of analysis and minimizing interpretive biases embedded in habit, tradition, or personal point of view. Curatorial practice is enhanced by the data-driven insights to inform their exhibition design, conservation work, and collection management as well as educators also have strong tools to develop visual literacy and help the public to engage further. The ease of the machine vision is further democratized by providing interactive guiding services, automated descriptions, and customized interpretive systems, which makes people more involved in the art-viewing process and achieves the inclusion of more individuals in the aesthetic discussion. However, the final part affirms the importance of integration that should be done with caution. The machine vision systems should be created in a sensitivity to cultural sensitivity, depth and ethical accountability without simplistic readings or unconstrained algorithm biases.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Ajorloo, S., Jamarani, A., Kashfi, M., Haghi Kashani, M., and Najafizadeh, A. (2024). A Systematic Review of Machine Learning Methods in Software Testing. Applied Soft Computing, 162, Article 111805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2024.111805

Barglazan, A.-A., Brad, R., and Constantinescu, C. (2024). Image Inpainting Forgery Detection: A Review. Journal of Imaging, 10(2), Article 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging10020042

Brauwers, G., and Frasincar, F. (2023). A General Survey on Attention Mechanisms in Deep Learning. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, 35(4), 3279–3298. https://doi.org/10.1109/TKDE.2021.3126456

Chen, G., Wen, Z., and Hou, F. (2023). Application of Computer Image Processing Technology in Old Artistic Design Restoration. Heliyon, 9(10), Article e21366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e21366

Cheng, M. (2022). The Creativity of Artificial Intelligence in Art. Proceedings, 81(1), Article 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2022081110

Dobbs, T., and Ras, Z. (2022). On Art Authentication and the Rijksmuseum Challenge: A Residual Neural Network Approach. Expert Systems with Applications, 200, Article 116933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2022.116933

Guo, D. H., Chen, H. X., Wu, R. L., and Wang, Y. G. (2023). AIGC Challenges and Opportunities Related to Public Safety: A Case Study of ChatGPT. Journal of Safety Science and Resilience, 4(4), 329–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnlssr.2023.08.001

Leong, W. Y., and Zhang, J. B. (2025). AI on Academic Integrity and Plagiarism Detection. ASM Science Journal, 20, Article 75. https://doi.org/10.32802/asmscj.2025.1918

Leong, W. Y., and Zhang, J. B. (2025). Ethical Design of AI for Education and Learning Systems. ASM Science Journal, 20, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.32802/asmscj.2025.1917

Lou, Y. Q. (2023). Human Creativity in the AIGC Era. Journal of Design, Economics and Innovation, 9(4), 541–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2024.02.002

Messer, U. (2024). Co-Creating Art with Generative Artificial Intelligence: Implications for Artworks and Artists. Computers in Human Behavior: Artificial Humans, 2, Article 100056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbah.2024.100056

Oksanen, A., Cvetkovic, A., Akin, N., Latikka, R., Bergdahl, J., Chen, Y., and Savela, N. (2023). Artificial Intelligence in Fine Arts: A Systematic Review of Empirical Research. Computers in Human Behavior: Artificial Humans, 1, Article 100004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbah.2023.100004

Schaerf, L., Postma, E., and Popovici, C. (2024). Art Authentication with Vision Transformers. Neural Computing and Applications, 36, 11849–11858. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-023-08864-8

Shao, L. J., Chen, B. S., Zhang, Z. Q., Zhang, Z., and Chen, X. R. (2024). Artificial Intelligence Generated Content (AIGC) in Medicine: A Narrative Review. Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering, 21(2), 1672–1711. https://doi.org/10.3934/mbe.2024073

Zaurín, J. R., and Mulinka, P. (2023). Pytorch-Widedeep: A Flexible Package for Multimodal Deep Learning. Journal of Open Source Software, 8(82), Article 5027. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.05027

Zeng, Z., Zhang, P., Qiu, S., Li, S., and Liu, X. (2024). A Painting Authentication Method Based on Multi-Scale Spatial-Spectral Feature Fusion and Convolutional Neural Network. Computers and Electrical Engineering, 118, Article 109315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2024.109315

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.