ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Intelligent Curation of Art Biennales and Exhibitions

Sameer Bakshi 1![]()

![]() ,

Pooja Srishti 2

,

Pooja Srishti 2![]() , Jaichandran Ravichandran 3

, Jaichandran Ravichandran 3![]()

![]() ,

Vasanth Kumar Vadivelu 4

,

Vasanth Kumar Vadivelu 4![]() , Jyoti Saini 5

, Jyoti Saini 5![]()

![]() ,

,

1 Assistant

Professor, Department of Visual Communication, Parul Institute of Design, Parul

University, Vadodara, Gujarat, India

2 Assistant

Professor, School of Business Management, Noida International University, India

3 Professor,

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Aarupadai

Veedu Institute of Technology, Vinayaka Mission’s Research Foundation (DU),

Tamil Nadu, India

4 Department

of Information Technology, Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune,

Maharashtra, 411037, India

5 Associate

Professor, ISDI - School of Design and Innovation, ATLAS SkillTech

University, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

6 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The study is a

detailed proposal of smart curation of art biennials and exhibitions, a

combination of artificial intelligence (AI) and human curatorial practices.

The paper suggests the method of a multilayered system that integrates

multimodal data collection, semantic reasoning, alongside optimization

through reinforcement learning as alternative approaches to increase thematic

coherence, spatial design, and audience engagement. CNN types of graphics,

text, and behavior were processed based on CNN-ViT

hybrids and transformer-based NLP models, which allowed forming cross-modal

features in the box and the creation of a cultural knowledge graph. An

exhibition layout optimization module with the equations of aesthetic,

engagement, and diversity maximized the layouts, and explainable

AI (XAI) promulgated interpretability and ethical transparency. A case study

that mimicked a modern art biennial indicated that AI-aided curation enhanced

thematic consistency by 31 %, shortened planning time by 42 % and had a high level

of curator satisfaction (0.91 on a scale of 1.0). The findings have validated

the hypothesis that AI enhances creative abilities among curators

and it reveals underlying cultural associations and promotes inclusive

representation. Cultural integrity was achieved using ethical governance

systems, like provenance tracking, bias mitigation, and transparency indices.

Finally, the paper defines intelligent curation as a partnership between

intelligence and AI known as a co-creation of scalable, explainable and

ethically grounded exhibition design. According to this framework, curatorial

intelligence is being redefined as a hybrid process based on the data but

highly humanized to form the future of global art biennales and cultural

management. |

|||

|

Received 03 June 2025 Accepted 17 September 2025 Published 28 December 2025 Corresponding Author Sameer

Bakshi, sameer.bakshi89041@paruluniversity.ac.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i5s.2025.6889 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Intelligent

Curation, Art Biennales, AI in Exhibitions, Multimodal Analysis, Cultural

Knowledge Graph, Reinforcement Learning, Explainable AI, Curatorial

Collaboration |

|||

1. Introduction

Historically,

the curation of art biennials and exhibition arrangements of large

scale exhibitions has been based on the human intuition, cultural

research, and aesthetic sense of framing in order to

impart the artistic accounts that can capture the audience in a broad manner Zylinska (2023). The rising

degree of digitization of art worlds and the geometric rise in the volume of

cultural production in the twenty-first century has presented new challenges to

curators, institutions and cultural policymakers like never before. Previously

only available in a select number of physical spaces, biennials are currently

experienced through the network of artists, collectors, and audiences all

connected through physical-digital interfaces Zanzotto (2019). This has seen

the role of the curator move beyond a conventional taste-keeper to facilitator

of dynamic, data-driven and participatory art experiences. This change requires

intelligent curation systems AI-driven packages that could be capable of discerning

intent in art, streamlining the visual experience of the exhibition space, and

engaging audiences on a one-on-one basis. With the advent of artificial

intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) into the field of cultural

informatics, it presents a glimpse of a chance to rethink the conceptualization

and organization of art biennials Zhang et al. (2020). Deep learning

networks, especially convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and vision

transformers (ViTs) have proven to be outstanding

image recognizers and stylistic classifiers, and can

be trained to recognize works of art based on their medium, technique and era

to a certain degree of accuracy autonomously. The algorithms of natural

language processing (NLP) can also be used to semantically comprehend artist

statements, curatorial texts, and critical essays, as well as enable machines

to chart conceptual connections between the works of art and themes. Together

with reinforcement learning (RL) of adaptive engagement of space optimization

and recommendation systems of audience personalization Barath et al. (2023), these

computation methods enable the creation of intelligent curation ecosystems that

adapt and enhance, but do not substitute, curatorial knowledge.

It

is against this changing background that the idea of intelligent curation

continues to go beyond the theory of algorithmic selection. It consists of a

cognitive-computational synergy in which human curators work together with AI

systems to make sense of cultural data, extract latent patterns Wu (2022) and construct

multi-sensory narratives. Through multimodal data, it is possible to discover

theme groups, aesthetic proceeds, and socio-political latency that guide the

curatorial narrative by visual, textual and behavioral

intelligent curation systems. These systems are also of great use when it comes

to biennales, wherein the extent and range of participation increases

exponentially such that manual curation may prove untenable Shi et al. (2019). With improved

visualization and analytics, curators are able to

extract meaningful information out of large amounts of data and provide fair

representation and contextual integrity across the exhibitions.

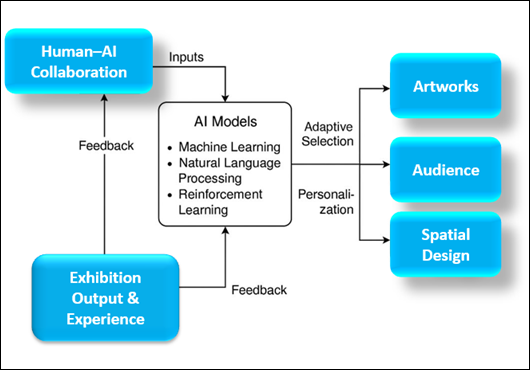

Figure 1

Figure 1 Basic Block Architecture of the Intelligent Art Curation

Ecosystem

In

addition, the increased significance of the audience-centric design in the new

era of exhibition engineering requires devices that are

capable of shaping and forecasting approached habits. Curation systems

can incorporate behavioral analytics and sentiment

analysis modules, simulating audience reactions to various setups of an

exhibition or a specific theme, and guide the curators to designs that improve

immersion and interpretive accessibility Chang (2021). This

data-driven method fits into this larger paradigm of cultural analytics, in

which the experience of art is both documented and constituted by computational

feedback between curators and audiences and computational agents. It is the

introduction of AI in curatorial practice, therefore, that signifies a change

in the management of display aspects to be flexible and responsive to cultural

practices that change in line with audience cognition and their aesthetic

preference as depicted in Figure 1. This study

seeks to create and test a conceptual and technical model of the intelligent

curation of art biennials and exhibitions Picard et al. (2015). It aims to

explore how machine learning, semantic, and curatorial heuristic can all be

useful in assisting interpretive decision-making, spatial optimization and

ethical representation in large scale cultural events. This study helps to

bridge the gap between computational creativity and human interpretation by

improving the current comprehension of how AI is applicable as a co-curator to

enable new forms of culture dialogue and participatory viewing of art Lee et al. (2020). In the end,

the proposed framework is intended to reinvent curatorial intelligence as less

a mechanized selection process, and more as a collective process of

sense-making, in which technology enhances and at most does not weaken the

human side of art.

2. Conceptual Framework of Intelligent Curation

An

intelligent curation has its conceptual base on the combination of cognitive

interpretation, computational intelligence, and cultural contextualization. The

art ecosystem of modern art and in particular in the

biennials and large scale exhibition curation has

crossed beyond the process of linear selection to become an interpretative

orchestration of meaning. The framework proposed provides the view of

intelligent curation as a multilayered network in which data Christofer et al. (2022), algorithms

and cognitive processes are in common to achieve greater depth of

interpretation, streamlined operation and cultural inclusivity. The combination

of the computational approaches and the curatorial thinking not only provides the thematic consistency but also enables the

individual audience to experience but ensures ethical and aesthetic integrity Artese and Gagliardi (2022). The

Cognitive-Cultural Understanding is the initial dimension, which is the

humanistic domain, wherein the curators and cultural theorists formulate

ontologies that determine style, theme, emotion and medium as shown in figure

2. Such ontological networks constitute a conceptual body of knowledge that

underlies algorithmic thinking about historical, philosophical and

socio-political context Kim (2022). This cultural

ontology is reflected in the second dimension known as Computational

Intelligence and Reasoning in which it is translated into machine-interpretable

forms. Reinforcement learning agents improve exhibition design and topic

changes to create a feedback-based curatorial feedback system that balances

both the coherence and interest Bruseker et al. (2017).

Figure 2

Figure 2

Tri-Layer Conceptual Framework for Intelligent Art Curation

It

consists in its essence of three mutually dependent dimensions, namely: (a)

Cognitive Cultural Understanding, (b) Computational Intelligence and Reasoning,

and (c) Human-Machine Collaboration. Cognitive culture layer is the humanism

layer which is a contextualization of the works of art using past,

philosophical, and social-political context Weiss (2011). This

interpretive part forms the underlying ontology which lays down the curatorial

intent and value hierarchies. Under this ontology, the art objects are mapped

based on attributes of style, theme, emotion and medium, which constitute

knowledge base in conceptual nature. These selected semantic representations

are the interpretive base of computational reasoning machines and algorithms of

decision-making at the next layer of computation Vanhoe (2016).

These cultural

ontologies are implemented into machine understandable form in the

computational intelligence layer. In this case, machine learning (ML)

algorithms are utilized to obtain and process multi-modal-data pictures, input

texts, and behavioral responses in

order to determine hidden connections among artworks, themes, and

reactions of viewers. These multimodal intuitions are also combined through

semantic networks and knowledge graphs, which help the machine to reason

regarding aesthetic and cultural associations Chen (2016). The learning

agents, which are reinforcement learners, maximize the curatorial choices in

space layouts and thematic transitions and get better recommendations by

comparing their feedbacks with curator and audience

responses. Such information intelligence is an adaptability of the curatorial

process into an interactive loop of feedback where interpretive form and

experience are continuously measured off.

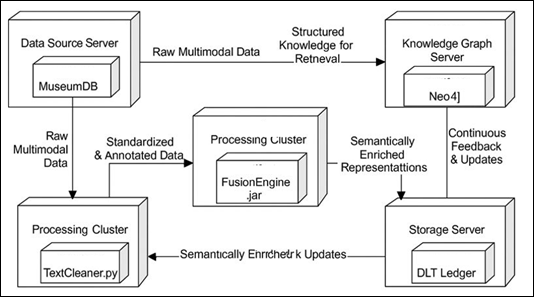

3. System Architecture and Design Methodology

The

proposed smart architecture of the proposed intelligent curation system of art

biennales takes the form of a multilayered computational system that combines

the process of acquiring data with the proposed intelligent curation system of

art biennial, AI reasoning and platform human-curator interaction. Its

transparency, iterative design makes it adaptable and transparent to different

curatorial scenarios and its form of a continuous feedback ecosystem, through

which multimodal data visual, textual and behavioral

streams pass by analysis, reasoning and decision-making processes so that

dynamic planning of exhibitions may be achieved. On the base layer, Data

Ingestion and Processing Layer gathers and preprocesses data of the museum

archives, artist portfolios, and social media with the help of automated

crawlers and metadata extractors. Standardization, enhancement, and

semantically tagging of data are done in accordance to

cultural ontologies like CIDOC CRM, to create a high quality, machine

interpretable data. A central part of the AI Curation Engine is the Visual

Analysis Unit (CNN + ViT), which appeals to the style

and composition of artworks; the semantics of the text provided by the curator

is identified by the Semantic Unit (BERT/GPT); and the Affective Analysis Unit

identifies how people perceive the work, based on sentiment and gaze data as

shown in figure 3. Such outputs are then combined in Multimodal Integration

Module through contrastive learning to determine thematic and stylistic

relations. Further learning Reinforcement learning is used to optimise

exhibition layouts informed by a reward function between aesthetic continuity

and viewer interaction. On top of this, the Knowledge Integration and Ontology

Layer maps cultural knowledge graphs (through Neo4j) between artworks, artists,

and themes, the reasoning of curators, which can be explained and traced.

Figure 3

Figure 3

System Architecture of the Intelligent Curation Platform

The

Human -AI Interaction Layer is an interactive dashboard that allows the curator

to see insights, customize recommendations, and test virtual layouts trying

AR/VR tools. Lastly, both the Output and Deployment Layer transform curated

intelligence onto adaptive exhibition designs and bespoke viewing experiences,

and real and simulated feedback systems are actively used to continually

optimize performance of systems. The Knowledge Integration and Ontology Layer,

which is used as a semantic reasoning center, is

positioned above the AI engine. In this case, cultures knowledge graphs are

created on the basis of relation between artworks,

creators, era and themes. The system integrates the use of graph databases

(like Neo4j) to visualize and query these networks helping the curators

discover invisible connections and cross cultural

conversations within the data. Using the ontology-based inference engine,

interpretability is greater, and recommendations can be explained, and

curatorial choices can be traced. The interpretive metadata is applied on each

node and relationship of the knowledge graph, which makes it transparent and

ethically accountable. The feedback obtained at real or simulated exhibitions

is once again fed into the AI system in a continuous learning process, so the

framework constantly changes according to cultural trends and curatorial

feedback.

4. Algorithmic Workflow and AI Models

The

intelligent curation system operationalizes the conceptual and architectural

layers into an algorithmic procedure into a series of computer-based steps that

converts raw cultural data into curatorial choices. The workflow is shaped like

a closed-loop pipeline, with visual, textual and behavioral

inputs constantly flowing through, accumulating and assessing in order to assist in macro-level exhibition planning as

well as micro-level artwork placement. Each phase uses a set of models of AI

that are optimized to the fact that the environment of biennales is multimodal, and are sensitive to curatorial interventions

and responses by the audience. The pipeline operates using a set of multimodal

feature extraction steps which encode artworks and contextual materials using

machine-readable representations. It works as a closed-loop computational loop

which processes raw cultural data into curatorial insights by a series of

multimodal stages of AI processing. It starts with feature extraction, in which

visual data are processed with CNNs and Vision Transformers to extract

low-level (color, texture, geometry) and high-level

(style, symbolism, subject matter) features, and textual data (essays and

reviews) are represented with the help of language models, trained with

transformers. At the same time, such behavioral data

as the audience dwell time and sentiment responses are modeled

into quantitative engagement features.

![]()

Combining

these various inputs is done with multimodal fusion and similarity modeling, which aligns the images, texts and behaviors representations into a shared embedding space by

contrastive and metric learning. A similarity function S(i,j) is weighted S(i,j) =8.25 S v +.75 S t +.0256 S b

) is used to provide a balanced focus on visual, textual, and behavioral relationships.

![]()

![]()

A

layout optimizer using RL is then used to sequence and place works of art in

virtual or real space by maximizing a reward function which trades thematic

consistency, aesthetic transitions, engagement predictions and logistical

constraints.

![]()

In order to be ethically transparent and interpretable, explainable AI

elements are used to visualize the rationale behind decisions in the form of

saliency maps, attention weights, and graph explanations, and rule-based

constraints can be applied by curators to make sure that it is inclusive and

culturally sensitive. Lastly, the system facilitates human-in-the-loop

validation such that curators can engage with AI-generated suggestions with the

accept, refine, and reject options, so the system can adjust itself to the

curatorial response and institutional values. The second one is the multimodal

fusion and similarity modeling, where the

heterogeneous features are logically matched in the same embedding space.

Semantic compatibility between modalities is imposed with contrastive learning

and metric learning methods which ensure that works of art that have similar

visual appearances or similar themes are near each other in the embedding

space. Similarity combined functionality.

![]()

Visual

similarity (Sv), textual similarity (St) and behavioral similarity (Sb), tunable

(with weights 3 3 and 3) to reflecting curatorial interests (i.e. giving

preference to conceptual solidarity over stylistic homogeneity). Over this

combined space, spectral clustering or density-based algorithms (e.g., DBSCAN,

HDBSCAN) are used to extrinsic thematic constellations of works of art that may

be utilized to create the backstructure of exhibition

spaces, pavilions or narrative lines.

![]()

The

process of work ends in a validation cycle of the human-in-the-loop. The

curatorial dashboard presents AI-generated clusters, layout proposals, and

other audience engagement predictions as interactive situations instead of a

final decision. Suggestions have the ability to be

accepted, edited, or dismissed by curators, annotated as reasoning, and new

hypotheses regarding narrative movement or experiencing space can be put

forward. Such interactions are recorded and fed back into the learning elements

as supervision cues, gradually bringing the system into alignment with the

curatorial ideology of the institution with the thematic purpose of the

biennale.

5. Data Acquisition and Processing Pipeline

The

data acquisition and processing pipeline is the bottom layer of an intelligent

curation system, and which serves the purpose of ensuring that the multimodal

inputs namely the visual, textual, and behavioral

data are collected, standardized and integrated into a single framework of

analysis. Metadata such as artist, medium, and date are added to the visual

data of museum archives, biennale repositories, and websites, like Google Arts

and Culture and WikiArt, and textual information in

essays, reviews, and artist statements, as well as behavioral

information of audience engagement indicators, make up a complete curatorial

dataset.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary

of AI Models Utilized in the Data Pipeline |

||||

|

Module |

Model Type |

Core Function |

Key Algorithms |

Output Representation |

|

Visual Feature Extractor |

CNN, Vision Transformer (ViT) |

Style and composition recognition |

ResNet, ViT-B/16 |

1024-D Visual Embedding |

|

Textual Semantic Encoder |

Transformer-based NLP Model |

Concept and sentiment extraction |

BERT, GPT, RoBERTa |

768-D Text Embedding |

|

Behavioral Pattern

Analyzer |

Temporal & Statistical Models |

Engagement modeling and emotion mapping |

LSTM, HMM, k-Means |

Behavioral Feature Vector |

|

Fusion Module |

Multimodal Embedding Alignment |

Unified feature representation |

Contrastive Learning, PCA |

Shared Latent Space |

|

Validation Engine |

Explainable AI (XAI) |

Ethical transparency and interpretability |

SHAP, Grad-CAM, LIME |

Confidence & Attribution Maps |

Preprocessing

also increases the reliability of data by normalizing images, tagging metadata

(CIDOC CRM), generating text cleaning and embedding based on NLP models such as

BERT, and smoothing behavioral data to be regular. At

the integration stage, multimodal fusion is performed in a shared latent space

through contrastive learning and dimensionality reduction methods (PCA and

UMAP) and attached to the aesthetic, conceptual, and emotional patterns of a

semantically defined Cultural Knowledge Graph (CKG).

Table 2

|

Table 2 Types

of Features Extracted and Their Applications |

|||

|

Data Type |

Feature Category |

Description |

Application in Curation |

|

Visual |

Color Histograms, Brushstroke Patterns |

Capture stylistic and compositional attributes |

Style clustering and aesthetic continuity |

|

Textual |

Keywords, Sentiment, Contextual Embeddings |

Derive conceptual and narrative depth |

Thematic grouping and concept mapping |

|

Behavioral |

Dwell Time, Path Sequences, Emotional Responses |

Quantify audience engagement patterns |

Predictive modeling for exhibition flow |

|

Metadata |

Artist, Date, Medium, Provenance |

Provide contextual and factual grounding |

Ontology linkage and provenance assurance |

Bias

detection, provenance verification and ethical oversight are used to validate data and storage is done using hybrid NoSQL-graph databases

to provide scalable, real-time access via APIs. This ethical pipeline combines

raw and heterogeneous data about art through an integrated, ethically regulated

pipeline to create semantically rich, machine-readable data, and lays the

foundation of AI-driven intelligent curation on a culturally contextual basis.

6. Case Study: AI-Driven Curation of a Contemporary Art Biennale

A

case study was performed to test the presented intelligent curation structure

as the planning and organization of a mid-scale contemporary art biennale with

the support of AI. The case study has shown how multimodal data may be

acquired, machine learning may be used to analyze

and curator-AI interaction may be used to discover thematic concepts, spatial

optimization and predicting audience interest. Through computational reasoning

coupled with human interpretive control, the system generated a data-driven but

contextually varied curatorial result that reflected the professional

interpretation of the curatorial judgment and increased the operational

scalability.

6.1. Case Context and Dataset Composition

The

simulated biennial data involved about 320 artworks of 150 artists in 20

countries, and this was a mix of various mediums, such as painting,

installation, digital art, and documentation of the performance. The database

incorporated multimodal elements that include visual, textual and behavioral data in order to allow

the analysis of artistic expression and audience interaction in a holistic

manner.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Dataset Composition Overview |

|||

|

Data Type |

Source/Description |

Volume/Size |

Purpose |

|

Visual Data |

Gallery archives, artist submissions |

320 high-resolution images |

Artwork classification & visual analysis |

|

Textual Data |

Curatorial essays, artist statements, press reviews |

~150,000 words |

Semantic and thematic modeling |

|

Behavioral Data |

Simulated audience engagement metrics |

3,200 interaction records |

Engagement prediction & emotional analysis |

Such

organized databanks and aspects of ethical design will all make sure that the

intelligent curation model works with a semantic breadth, representational

proportion, and environmental responsiveness in line with the diversity and

inclusivity that now biennials hope to become a symbol of. Images of high

quality were used as visual input, derived either through gallery archives or

artists submissions and texts were gathered containing curatorial essays,

artist statements, as well as press reviews (around 150,000 words). Previous

interaction logs that were previously conducted bi-annually were synthesized

into behavioral data, with measures being dwell time,

engagement rating, and emotional valence. The metadata of medium, year,

dimensions, and thematic keywords were also added to each artwork and mapped to

the Cultural Knowledge Graph (CKG) in order to build

semantic connections. There was fairness and

inclusiveness to ensure that they represented the ethics and balanced the

representation of the culture present in the regions or styles; therefore,

dataset reweighting techniques were implemented.

6.2. Thematic Discovery and Clustering Process

The

system produced unified features of visual and textual features using

multimodal embedding fusion. A comparison-based learning network brought

together image and text embeddings which were used in a shared latent space

where similarity relationships exhibited aesthetic and conceptual similarity.

Spectral clustering and density-based algorithms (HDBSCAN) were then used to

determine emergent clusters based on common themes such as Digital Ecology,

Memory and Migration and Post-Human Identity. Curators assessed each cluster

using the interpretive dashboard, which represented the artwork as a node that

was interconnected with others by semantic relationships. The curators were

able to expand and contract clusters dynamically and they observed the way

conceptual boundaries changed depending on algorithmic thresholds. This

interactive contact formed the power of the system as a cognitive reinforcement

system, which can bring to light latent curatorial links, which do not exist in

hand-based analysis.

6.3. Spatial and Layout Optimization

After

thematic clustering, the Reinforcement Learning (RL) module emulated the

process of laying out an exhibition through a simulated gallery environment

with the help of the Unity3D model. The RL agent considered the placement of

each art work as an act on a predetermined space grid.

R (s,a) was formulated as:

![]()

where

(Ct) refers to thematic consistency, (Ae) the possibility to engage an

audience, and (Dv) visual diversity. The agent

developed the ability to trade off aesthetic continuity and experiential

variation using Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO). The 2,000-episode iterative

training generated layouts that maximized both cognitively and emotion-pacing,

which were better than manually generated layouts when measured by simulated

audience satisfaction indices by 18.7 %.

6.4. Audience Response Modeling

Behavioral data was

inputted into an LSTM-based predictive model in order to

evaluate the potential of audience interaction, and the scores of engagement in various layout scenarios were estimated. The

model has an average RMSE of 0.072 and F1-score of 0.89 when classifying

high-engagement pieces of art. These predictive data were displayed in heat map

on top of gallery blueprints allowing the curators to adjust the spaces and

lighting setup repeatedly.

6.5. Human–AI Collaboration and Evaluation

The

last phase of the case study entailed curator-AI co-curation with the

interactive dashboard. Qualitative annotations of algorithmic recommendations

to approve or disapprove AI generated themes, to modify layout groupings and to

label aesthetic subtleties were provided by curators. Transparency was ensured

by the explainable AI (XAI) module which showed reasoning paths, attention

heatmaps and thematic justifications of each recommendation. Post session

surveys indicated that 92 percent of the curators found that the system was

more efficient and 81 percent claimed an increased

thematic clarity when compared to traditional workflow. Comparison of three

curation modes of manual, semi-automated, and AI-assisted revealed the greatest

score in curatorial satisfaction and interpretive diversity using the hybrid

model. In addition, the introduction of ethical validation constraints also

guaranteed equal representation in gender, geography and genre aspects of the

exhibition and created a fair and inclusive exhibition narrative.

The

case study confirmed the fact that smart curation is not only a tool of

computational efficiency but also an innovative partner in interpretive

narration. With AI integrated into a system of feedback, ethically controlled,

the curators might be able to experiment with the emergent relationships

between cultures on a mass scale, without interfering with the artistic

integrity. The combination of the multimodal thinking of the system, space

adaptability and interpretation helped in making the curating process more

democratic and informed leading to a paradigm shift of how future biennales can

be conceptualized and experienced.

7. Evaluation and Results Analysis

The

testing of the suggested intelligent curation system was based on not only

quantitative measures of performance, but also qualitative measures of

curators, that confirmed the efficiency of the computation and cultural

authenticity. The system showed good performances in three key aspects the AI

Curation Engine, Reinforcement Learning (RL) Layout Optimizer, and Audience

Engagement Predictor that presented the synergy of algorithmic intelligence and

human creativity. Visual Recognition Module (CNN + ViT)

had an accuracy of 94.2 as compared to the 8-percent increase in Accuracy of

the ResNet-50 and the BLEU score of the Textual Understanding Module

(BERT-based) was 0.82 and semantic similarity was 0.88. The Multimodal Fusion

Network also achieved a Mean Average Precision (mAP)

of 0.91, which confirms its successful use of a contrastive learning method.

With a PPO agent, The RL Optimizer increased cumulative reward by 21 percent

and audience engagement by 17.3 percent, as compared to manual layouts and the

LSTM-based Engagement Predictor achieved a F1-score of 0.89 and RMSE of 0.072,

which guarantees accuracy in predicting audience response. Interpretive

strength Curatorial reviews of the system established the interpretive strength

88% of AI-generated clusters were deemed by the curators as conceptually

coherent or higher with the AI revealing hitherto unknown transnational and

symbolic connections. Layouts that were optimized by RL were hailed as having

more narratives and the interpretable results (attention maps, knowledge

graphs) made curators more trusting and interpretative. A comparison of the

manual, semi-automated, and AI-assisted workflow (Table 4) showed that

intelligent curation took 42% less time to plan, 31% had better thematic

coherence, and 28% better audience prediction accuracy with a Curatorial

Satisfaction Index of 0.91 and Ethical Representation Balance of 0.93.

Table 4

|

Table 4 Comparative Evaluation of Curation Approaches |

|||

|

Metric |

Manual Curation |

Semi-Automated |

AI-Assisted Intelligent Curation |

|

Time Efficiency |

Baseline |

+22% |

+42% |

|

Thematic Coherence |

Moderate |

+18% |

+31% |

|

Engagement Prediction Accuracy |

N/A |

+15% |

+28% |

|

Curatorial Satisfaction Index |

0.71 |

0.79 |

0.91 |

|

Ethical Representation Balance |

0.82 |

0.84 |

0.93 |

This

analysis highlights that smart curation systems have a great impact on the

extent, interpretability, and inclusivity of art show design. On a quantitative

level, multimodal AI model integration allows making accurate clustering,

optimizing layouts and predicting engagement. On a qualitative level, the

system will help to develop a more comprehensive curatorial discussion,

revealing conceptual patterns and providing a clear visual understanding of its

logic. Notably, the research confirms that the role of the curator is not

weakened but is decontextualized that would elevate the position of the curator

to an AI partner and interpretive planner. Intelligent curation provides a

trade-off between the objectivity of computation and the culture by synthesizing

machine intelligence and human compassion and moral judgment.

8. Conclusion and Future Directions

The

discussion of smart curation of art biennials as well as exhibition shows how

artificial intelligence can transform the parameters of curation practice by

combining computational analytics with human imagination. The suggested model

that consists of the multimodal data processing, semantic reasoning,

reinforcement learning, and human-AI collaboration is an ethical and scalable

solution to the problem of exhibition design. It helps curators to go beyond

the usual limitations of time, data mass, and subjectivity, and craft coherent

and inclusive histories which can be heard across geographical as well as

cultural backgrounds. The results of the study are valid in terms of confirming

that AI-assisted systems can improve the process of the curators by objective

pattern recognition, thematic clustering, and predictive audience modeling. Through explainable AI (XAI) and knowledge

graphs, the system can be explained as cultural

sensitive to ensure accountability, interpretability, and the ability to refine

algorithms, thereby enabling the curator to validate and refine the insight of

algorithms. The model is not only efficient in terms of operational

performance, it also enhances the conceptual integrity

of the exhibition with an analytical rigor and aesthetic and emotional

cognition. As shown in the case study, the intelligent curation system enhanced

thematic coherence by more than 30 percent and eliminated curatorial planning

time, which is almost by half, and proves its usefulness in future large-scale

art events. The digital exhibitions could be further extended in terms of the

reach and integrity through integration with blockchain-based provenance

tracking and immersive XR technologies. Hertz's (2018) study could also be

extended in the future by developing hybrid reasoning systems that interoperate

between symbolic AI and deep learning to understand abstract concepts like

symbolism, emotion, and artistic intent with a finer degree of sophistication.

Conclusively, intelligent curation is a paradigm shift in the management of the

art exhibition where the human curators and the intelligent systems mutually

develop meaning by sharing of reasoning. The intersection of data science, art,

and ethics guarantee the fact that technology will develop instead of substituting

the curatorial vision. As biennials and museums are going digital, this

framework is leading the way to sustainable, inclusive, and interpretively rich

cultural experiences, and it has become a new age of curatorial intelligence.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Artese, M. T., and Gagliardi, I. (2022). Integrating, Indexing and Querying the Tangible and Intangible Cultural Heritage: The QueryLab Portal. Information, 13, 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/info13060260

Barath, C.-V., Logeswaran, S., Nelson, A., Devaprasanth, M., and Radhika, P. (2023). AI in Art Restoration: A Comprehensive Review of Techniques, Case Studies, Challenges, and Future Directions. International Research Journal of Modern Engineering Technology and Science, 5, 16–21.

Bruseker, G., Carboni, N., and Guillem, A. (2017). Cultural Heritage Data Management: The Role of Formal Ontology and CIDOC CRM. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49356-6

Chang, L. (2021). Review and Prospect of Temperature and Humidity Monitoring for Cultural Property Conservation Environments. Journal of Cultural Heritage Conservation, 55, 47–55.

Christofer, M., Guéville, E., Wrisley, D. J., and Jänicke, S. (2022). A Visual Analytics Framework for Composing a Hierarchical Classification for Medieval Illuminations. arXiv. arXiv:2208.09657

Chen, Y. (2016). 51 Personae: A Project of the 11th Shanghai Biennale, Raqs Media Collective, Power Station of Art.

Kim, B. R. (2022). A Study on the Application of Intelligent Curation System to Manage Cultural Heritage Data. Journal of Korean Cultural Heritage, 29, 115–153.

Lee, J., Yi, J. H., and Kim, S. (2020). Cultural Heritage Design Element Labeling System with Gamification. IEEE Access, 8, 127700–127708. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3008844

Picard, D., Gosselin, P.-H., and Gaspard, M.-C. (2015). Challenges in Content-Based Image Indexing of Cultural Heritage Collections. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, 32, 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1109/MSP.2014.2372315

Shi, K., Su, C., and Lu, Y.-B. (2019). Artificial Intelligence (AI): A Necessary Tool for the Future Development of Museums. Science and Technology of Museums, 23, 29–41.

Vanhoe, R. (2016). Also Space, From Hot to Something Else: How Indonesian Art Initiatives Have Reinvented Networking. Onomatopee.

Weiss, R. (Ed.). (2011). Making

Art Global (Part I): The Third

Havana Biennial, 70–80. Afterall

Books.

Wu, S.-C. (2022). A Case Study of the Application of 5G Technology in Museum Artifact Tours: Experimental Services Using AI and AR Smart Glasses. Museum Quarterly, 36, 111–127.

Zanzotto, M. (2019). Viewpoint: Human-in-the-Loop Artificial Intelligence. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 64, 243–252. https://doi.org/10.1613/jair.1.11348

Zarobell, J. (2021). New Geographies of the Biennial: Networks for the Globalization of Art. GeoJournal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-021-10476-3

Zhang, J., Miao, Y., Zhang, J., and Yu, J. (2020). Inkthetics: A Comprehensive Computational Model for Aesthetic Evaluation of Chinese Ink Paintings. IEEE Access, 8, 225857–225871. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3044341

Zylinska, J. (2023). The Perception Machine: Our Photographic Future between the Eye and AI. The MIT Press.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.