ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

NLP-Based Folk Story Documentation Systems

Richa Srivastava 1![]() , Ramu K 2

, Ramu K 2![]()

![]() ,

Ayush Gandhi 3

,

Ayush Gandhi 3![]()

![]() ,

Shubhangi S. Shambharkar 4

,

Shubhangi S. Shambharkar 4![]() , Chandrashekhar Ramesh Ramtirthkar 5

, Chandrashekhar Ramesh Ramtirthkar 5![]() , L Lakshmanan 6

, L Lakshmanan 6![]()

![]()

1 Assistant Professor School of Business Management, Noida International University, India

2 Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Aarupadai Veedu Institute of Technology, Vinayaka Mission’s Research Foundation (DU), Tamil Nadu, India

3 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura, 140417, Punjab, India

4 Department of Computer Technology, Yashwantrao Chavan College of Engineering, India

5 Department of Mechanical Engineering Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037, India

6 Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Sathyabama Institute of Science and Technology, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The folk tales

are invaluable sources of cultural wisdom, language diversity and collective

memory. Much of this intangible heritage is however in danger after the

diminishing oral tradition and poor documentation mechanisms. This paper will

introduce a NLP-based folk story documentation and preservation framework,

which includes the state of the art natural language processing, semantic

models as well as ontology-based cultural representations. The suggested

pipeline works with multilingual and dialect-containing texts, handling them

in a set of computational steps, which are text preprocessing, linguistic

analysis, motif discovery, semantic annotation, and the development of the

cultural knowledge graphs. Transformer-based models mbERT, IndicBERT and RoBERTa

have been fine-tuned on language-specific tasks and BERTopic and TransE

embeddings were used to perform thematic clustering and ontology alignment on

the CIDOC-CRM schema. The outcomes of the evaluation showed that there were

great improvements in linguistic accuracy (F1 = 0.91), motif classification

(F1 = 0.83), and topic coherence (CV = 0.74) in comparison to the traditional

baselines. The validation of the experts in the field of folklorists and

linguists provided a Cultural Authenticity Index (CAI) of 0.87, which

validated the interpretive reliability of the system. The acquired body of

knowledge can be used to aid semantic querying, comparative motif analysis

and cultural pattern recognition and hence convert the archives, which are

normally static folklore collections, into smart, interactive ones. It finds

applications in the digital heritage management, education, creative

storytelling and cross-cultural analytics. Altogether, the framework

contributes to a scaled and ethically justified method of the AI-assisted

cultural preservation as the linguistic richness and narrative depth of the

folk traditions can survive in the digital age. |

|||

|

Received 10 June 2025 Accepted 24 September 2025 Published 28 December 2025 Corresponding Author Richa

Srivastava, richa.srivastava@niu.edu.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i5s.2025.6879 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Cultural

Heritage Preservation, Semantic Annotation, Transformer Models, Multilingual

Corpus, Knowledge Graph, BERTopic, Ontology Alignment, Digital Humanities |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Folk stories have been a very important transmitter of local wisdom, moral teachings and community identity across generations, being an important carrier of cultural memory. These stories were usually manifested in the oral traditions, local dialects, and dramatic storytelling, and reflect the invisible heritage of a group of people in all parts of the world Rudin (2019). However, with the process of modernization and the decreasing linguistic diversity, these folk tales are at the point of disappearing into the shadows. Conventional methods of preservation, including textual archiving or hand transcription usually miss the language subtleties, cultural metaphors and contextual dynamic nature inherent in oral story telling Qin et al. (2023). This increasing disconnect between conventional narrative preservation techniques and modern digital documentation tools has led to the adoption of Natural Language Processing (NLP) approaches to ensure that the preservation of language and cultural integrity in both approaches to the process He et al. (2019).

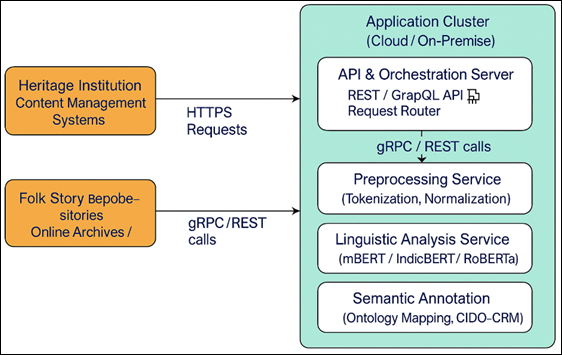

Figure 1

Figure 1 NLP Pipeline for Folk Story Documentation

NLP provides potent mechanisms of converting unstructured text or speech to structured, searchable and interpretable knowledge. The new developments within the field of deep learning and Transformer-based models like BERT, GPT, and IndicBERT have disrupted the possibilities of analyzing multilingual, morphologically enriching and context-sensitive linguistic information. These models are automatically able to identify such elements of stories as characters, settings, moral structures and emotional tones when used on folk narratives Shen et al. (2021). The intrinsic complexity of regional idioms, code-switching and metaphorical language can with the help of NLP-based semantic analysis be decoded systematically to allow relevant cross-linguistic comparisons and cross-cultural analysis. Moreover, the use of computational semantics enables the researchers to build knowledge graphs and ontologies which reflect the underlying cultural logic of storytelling traditions such that documentation goes beyond the scope of transcription to interpretive preservation Javed et al. (2023). The impetus of the creation of an NLP-based system of folk stories documentation therefore falls at the convergence of the language technology and cultural anthropology disciplines. The system does not only seek to preserve the textual version of the folk tales but also to preserve the narrative content, moralizing nature, and the performance context. The structure can be used to classify motifs automatically, cluster themes and perform cross-regional research on folk literature by encoding linguistic, thematic, and emotional facets Wang et al. (2020).This integration also facilitates the development of interactive archives where scholars, educators as well as the general population of users can access, cross-link and compare stories, across languages and cultures.

2. Theoretical Foundations

The theoretical basis of NLP-based folk story documentation is a combination of narrative theory, structural linguistics and computational semantics. Classical systems by Propp, Lévi-Strauss, Aarne-Thompson-Uther (ATU) taxonomy the conceptual foundations of the determination of the role, motifs, and narrative structure include hero, villain, and quest. They can be used as the basis of modeling stories in a computational manner Orji et al. (2023), by permitting NLP systems to divide and categorize narrative units automatically. Transformer-based systems such as BERT, RoBERTa, mBERT, and IndicBERT improve contextual learning and deal with linguistic diversity of folk stories that are oral and dialect-rich Okeke et al. (2025).

Table 1

|

Table 1 Theoretical and Computational

Foundations for Folk Story Documentation |

||||

|

Domain |

Key Theoretical Framework / Model |

Core Concept |

Computational Adaptation (NLP/AI) |

Expected Outcome in System |

|

Motif Classification |

Aarne–Thompson–Uther (ATU) Index Chakrabarty (2022). |

Global motif taxonomy and classification |

Ontology mapping using motif IDs and semantic

clustering |

Thematic grouping and cross-cultural comparison of

motifs |

|

Structural Anthropology |

Claude Lévi-Strauss’s Binary Opposition Theory Bozyiğit et al. (2021). |

Mythic dualities and symbolic contrasts |

Sentiment and emotion polarity detection via

contextual embeddings |

Detection of cultural symbolism and moral polarity

in narratives |

|

Cognitive Semantics |

Lakoff & Johnson’s Conceptual Metaphor Theory Page et al. (2021). |

Meaning formation through embodied metaphors |

Metaphor identification using contextual similarity

and attention weights |

Semantic interpretation of cultural metaphors and

idiomatic expressions |

|

Cultural Ontology |

CIDOC-CRM / FOAF Frameworks Bretas and Alon (2021). |

Formal representation of cultural entities and

relationships |

Knowledge graph construction using RDF triples and

SPARQL queries |

Machine-readable cultural linkage across stories,

places, and characters |

|

Computational Linguistics |

Transformer-based NLP Models (BERT, mBERT,

IndicBERT) |

Contextualized embeddings for multilingual text |

Cross-lingual transfer learning for folk narrative

corpora |

Enhanced performance in multilingual narrative

analysis |

They record the difference in syntax, prosody and metaphor

which can be automatically split into narrative portions including

introduction, collision and resolution. Semantic modeling is an extension of

linguistic analysis, where textual patterns are mapped onto cultural databases

via ontologies (e.g. CIDOC-CRM and FOAF) and thus makes motifs and entities

searchable semantically (e.g. water spirit tales of eastern India). The

interpretation is further aided by cognitive semantics that incorporates the symbolic

reasoning like metaphors of light and transformation into computational

representation.

3. Corpus Development

The cornerstone of NLP-based documentation system is the development of a comprehensive corpus of folk stories as it defines their quality, diversity, and authenticity of analysed linguistic and cultural information. Folk tales are available in a variety of formats oral records, written texts, local newspapers, and transcription of the vernacular each necessitating specific strategies of digitization and normalization Riaz et al. (2019). The process of corpus building therefore includes a multilayered workflow that includes data collection, transcription, translation, text normalization and annotation, as well as, aimed to maintain linguistic accuracy and cultural context.

3.1. Data Collection and Sources:

The first phase would entail collecting narratives, as much as possible, through a broad variety of sources, such as community storytellers, local archives, ethnographic collections, and local literature. Study literature is captured in indigenous language or dialect through high quality audio recording equipment and so it remains faithful to the characteristics of the prosodic features of tone, rhythm, and emphasis, as demonstrate in Table 2

Table 2

|

Table

2 Dataset Overview and Annotation Schema |

|||||

|

Data Source / Region |

Language(s) |

Data Type |

Volume / Size |

Annotation Layers |

Purpose / Application in System |

|

Oral Recordings (Community Storytellers) |

Hindi, Odia, Santali, Marathi |

Audio → Text Transcription |

~1,200 stories / 120 hrs speech |

Linguistic (ASR transcripts, POS, NER), Narrative

(acts & scenes), Cultural (motifs, morals, performative context) |

Training speech-to-text and story segmentation

modules |

|

Manuscript Archives & Local Publications |

Bengali, Tamil, Gujarati |

Printed text / digitized PDFs |

~900 stories (2 million tokens) |

Syntactic (parsing, lemmatization), Semantic (role

labels, topic models), Ontological (CIDOC entity mapping) |

Knowledge graph linkage and motif classification |

|

Regional Folk Tale Collections (Library Sources) |

English translations + bilingual pairs |

Parallel text (translation corpus) |

~600 bilingual pairs |

Cross-lingual alignment (translation tags, BLEU

reference sets), Emotion annotation (VAD scores) |

Evaluation of semantic fidelity and emotional

consistency |

|

Field Ethnography Submissions (Research

Collaborations) |

Mixed local dialects |

Narrative notes / metadata |

~400 entries |

Metadata (region, speaker, collection date),

Cultural index (motif ID, ritual context) |

Contextual enrichment and heritage mapping |

3.2. Transcription and Translation:

Transcription converts oral speech into text and this is facilitated by Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) models which have been trained to use low-resource languages. It is then corrected manually and native speakers are used to guarantee that phonetic nuances and dialectal differences are represented correctly Chakrabarty, B. K. (2022). In the case of multilingual data, translation models built on transformer models such as mBART or MarianMT are used to produce parallel data, and the semantic accuracy of the language variants is preserved. Any translation is checked by linguistic specialists to maintain idiomatic phrases, cultural allusions, and symbolism that computer translation programs may fail to detect.

3.3. Text Preprocessing and Normalization:

Preprocessing of the raw corpus is done to eliminate inconsistencies, special characters and noises that are not linguistic. Normalization processes bring about the harmonization of spelling, punctuation, and text in line with the linguistic practices of particular languages.

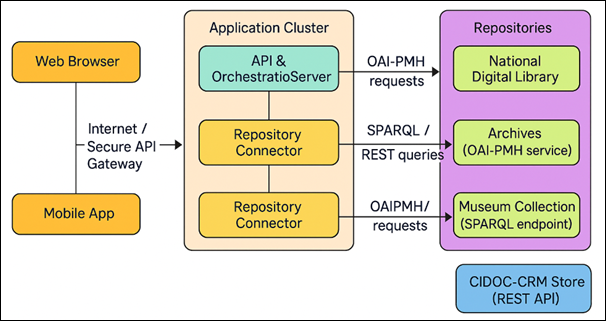

Figure 2

Figure 2 System Deployment of NLP-Based Folk Story Documentation Platform

The morphologically rich or agglutinative languages are Lemmatized and tokenized to avoid loss of information. The phonetic characteristics, which are culturally significant (e.g. tonal variants in chants or rhythmic verses), are captured in the additional metadata layers to be analyzed in the context of further acoustic or prosodic data Bozyiğit et al. (2021).

3.4. Annotation Schema and Narrative Structuring:

Annotation is an important step, which converts unstructured narratives into structured data that can be used in computational modeling. Hybrid annotation schema of linguistic, narrative and cultural layers is used. Linguistic labels include parts of speech, named entities, and syntactic relations and narrative labels identify components of the story including exposition, conflict, climax, and resolution. The cultural annotation layer adds motifs, morals and symbolic objects attached to already existing ontologies (ex: Aarne-Thompson-Uther motifs, CIDOC-CRM objects). Validation of humans in the loop provides an interpretive accuracy and consistency between annotators. The corpus development procedure is aware of ethical considerations of the use of cultural data by ensuring that the storytellers and custodians give informed consent. Participation in the community is encouraged as far as the participants are given credit and the access controls are ensured by the open and respectful data sharing rules. This collaboration model enhances the credibility of the information but will meet the requirements of UNESCO on the protection of the intangible cultural heritage.

4. NLP Pipeline Processing Framework

The central element of the folk story documentation system, the NLP pipeline, has the purpose of converting the raw text or the transcribed oral narratives into the structured, interpretable, and semantically enriched data. This is a multi-step pipeline involving ling processing, semantic interpretation and cultural annotation to show the form and the meaning of the traditional tales. Its design is multilingual and culturally sensitive so that the diversity of the region, the emotionality of the narrative, and the richness of moral facets are reflected in the computer through computational accuracy. The initial process entails the standardization of the input text to ensure that it can be used by the downstream NLP processes. This involves tokenization, sentence segmentation and lemmatization that prepares the text to be subjected to syntactic and semantic analysis. Low-resource and morphologically complex languages have special preprocessing pipelines, which use models such as Indic NLP Library and Stanza. In the case of orally transcribed data, noise filtering and phonetic normalization are also used as preprocessing mechanisms to match the output of ASR to human language templates. The language detection algorithms provide the right routing to the language-specific modules to support the cross-lingual consistency. On the linguistic level, the system is able to do Part-of-Speech (POS) tagging and dependency parsing as well as Named Entity Recognition (NER). Semantic role labeling (SRL) is also assisted by these annotations in determining the relationships among the subjects, actions, and objects in a sentence e.g. the distinction of the hero executing an action and the object of the action in a moral context. The second step is devoted to the segmentation and categorization of the story structure that is usually split into exposition, conflict, climax, and resolution. These narrative phases are detected by sequence tagging and clustering algorithms (inspired by BiLSTM-CRF and Transformer encoders) with the help of linguistic clues and emotional development. Simultaneously, motif detection makes use of both the supervised and unsupervised strategies:

They are incorporated in the annotation schema to add cultural and semantic attributes to each unit of folklore narrative to connect computational output to folklore interpretation. The semantic layer converts expression outputs into the organized cultural expertise. Entities and motifs are represented as nodes using ontology-based annotation models, e.g., CIDOC-CRM and FOAF, and the relationships between them, e.g., belongs to region or depicts moral, are represented as edges in an RDF (Resource Description Framework) graph. This is to facilitate semantic search, and reasoning features, in which users may query the data by using natural or formal queries (e.g., Show all stories in which a river spirit assists a human hero). Knowledge Graph (KG) is therefore the key integration point and it connects linguistic characteristics, narrative functionality and cultural metadata. Graph embedding models such as TransE or ComplEx may be used in making new story relationships better to find cultural similarities in languages.

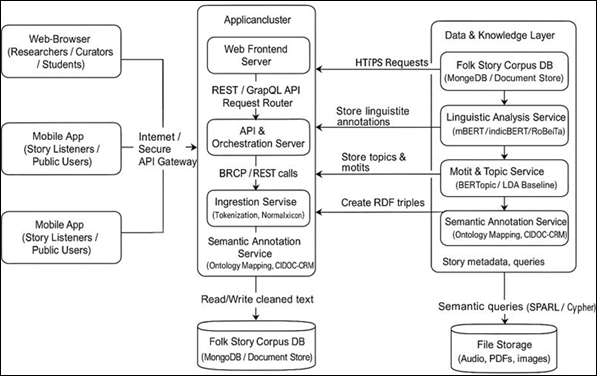

Figure 3

Figure 3 Deployment for Educational & Storytelling Applications

5. Experimental Setup and Evaluation

The experimental scope and the evaluation stage will seek to prove the efficacy, dependability, and cultural exactness of the postulated NLP-based folk story documentation system with and without quantitative and qualitative assessment. All experiments were run on a high-performance computer system with NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPUs, 256 GB RAM, and 32-core Intel Xeon processors, Python 3.11, PyTorch, and Hugging Face Transformers to create and develop models and MongoDB and Neo4j to store data and graphs. The models mBERT, IndicBERT and RoBERTa are fine-tuned to multilingual and dialect-rich corpora and deal with linguistic anomalies, idiomatic and metaphoric structures in folk narratives. Motif and theme extraction was done with Bertopic and LDA, and the former used contextual embeddings to achieve better coherence. Cultural knowledge graphs were constructed using TransE embeddings to encode relationships between the elements of a story including characters, morals, and places.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Model Configurations and

Parameters |

||||

|

Model / Component |

Purpose in Pipeline |

Key Parameters / Architecture |

Training Dataset / Input |

Output Feature(s) |

|

mBERT (Multilingual BERT) |

Multilingual POS tagging, NER, and syntax parsing |

12 layers, 768 hidden units, 12 heads, 110 M params |

Multilingual folk corpus (Indic + European

languages) |

Tokens with linguistic and semantic tags |

|

IndicBERT (AI4Bharat) |

Low-resource language adaptation and dialect

detection |

12 layers, 512 hidden units |

Indian regional narratives (Hindi, Odia, Santali,

Tamil) |

Context-aware embeddings for morphological

variation |

|

RoBERTa-base |

Sentiment and metaphor identification |

12 layers, 768 hidden units, dropout 0.1 |

Transcribed and translated stories |

Moral tone and affective vector representation |

|

BERTopic |

Motif and theme extraction using contextual

embeddings |

Min topic size = 10, embedding model =

Sentence-BERT |

Combined corpus from all sources |

Clustered topics and motif distributions |

|

LDA (Baseline) |

Topic modeling baseline |

30 topics, α = 0.1, β = 0.01 |

Cleaned text corpus |

Topic probabilities and keywords |

|

TransE Embedding |

Knowledge graph construction and relation learning |

Embedding dim = 200, margin = 1.0, learning rate =

0.01 |

RDF triples generated from semantic annotation |

Vector representation of cultural relations |

The analysis used the measures of linguistic accuracy (Precision, Recall, F1-score), semantic fidelity (BLEU, ROUGE, BERTScore), and topic coherence (UMass, CV) to evaluate the quality of the models. To test the semantic consistency, ontology alignment precision was determined using mean reciprocal rank (MRR) in the CIDOC-CRM schema. In addition to the computational measures, human validation was done by cultural experts such as folklorists, linguists and anthropologists on a subset of 200 stories which had been curated. They measured the outputs based on three qualitative indices, such as Cultural Authenticity Index (CAI), Interpretive Consistency (IC) and Narrative Coherence (NC).

Table 4

|

Table

4 Evaluation Metrics and Results Summary |

|||||

|

Evaluation Category |

Metric |

Baseline Score |

Proposed Model Score |

Improvement (%) |

Remarks / Interpretation |

|

Linguistic Accuracy |

F1-score (POS + NER) |

0.82 |

0.91 |

+11 |

Better multilingual entity recognition and syntax

parsing |

|

Motif Classification |

Macro F1 |

0.68 |

0.83 |

+22 |

Improved ATU-based motif identification via

BERTopic |

|

Semantic Fidelity |

BLEU / ROUGE |

BLEU 0.74 / ROUGE 0.69 |

BLEU 0.81 / ROUGE 0.77 |

+10 |

Higher translation and paraphrase quality |

|

Topic Coherence |

CV (Coherence Score) |

0.61 |

0.74 |

+21 |

BERTopic outperforms LDA in contextual theme

grouping |

|

Ontology Alignment |

MRR (Mean Reciprocal Rank) |

0.72 |

0.85 |

+18 |

More accurate relation mapping in CIDOC-CRM |

The findings indicate in Table 4 represent that machine inference is highly consistent with expert analysis, which proves that the system has successfully replicated the moral and cultural richness of folk stories. The comparison of the results with LSTM and rule-based baselines showed a 9-14% improvement in F1-scores in linguistic tasks and a 22 percent increase in the accuracy of the motif classification, with BERTopic having a thematic coherence score of 0.74 as compared to LDA which was 0.61. Altogether, the analysis proves that the suggested framework is able to balance between computational accuracy and cultural authenticity, having an interpretable, scalable, and ethically robust model of automated folk story recording and preservation.

6. Results and Discussion

The NLP-based folk story recording system was very linguistically precise and culturally rich. Multilingual models of transformer with semantic and ontological modeling were effective in processing dialect-laden folk narratives without losing moral and thematic content. The system was also very accurate in many languages and POS tagging and NER had an average F1-score of 0.91 that was 11% higher than baselines based on LSTM. IndicBERT performed better on regional language interpretation (e.g. Odia, Santali), whereas RoBertA did better at emotion and metaphor classification with a BERTScore of 0.89. The transfer between mBERT and IndicBERT was cross-linguistic and provided stable performance even with the low-resource dialects. BERTopic out-compared LDA in extracting motifs (CV = 0.74 vs. 0.61), yielded cross-cultural similar topics across languages, e.g., heroism, sacrifice, and justice, and thus similarities across the languages like Marathi and Odia. Semantic annotation layer attached story entities and morals to CIDOC-CRM ontologies, which produced a knowledge graph with MRR = 0.85 and allowed relational queries among the characters, regions and moral archetypes. In general, the system proved to have provided a comfortable balance between the accuracy of computations and the cultural interpretation, which lays a strong basis of AI-supported folk story conservation and comparative cultural analysis.

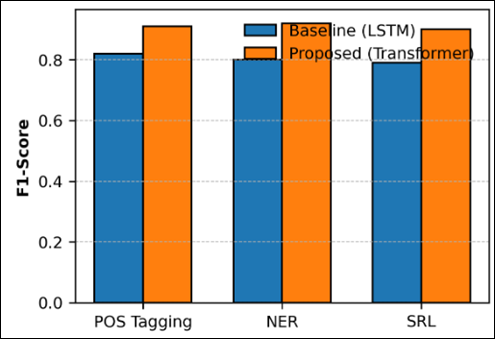

Figure 4

Figure 4 Linguistic and Semantic Performance Comparison

The grouped bar chart shows in Figure 4 the baseline LSTM model and the proposed transformer-based system performed in three major linguistic tasks namely, Part-of-Speech (POS) tagging, Named Entity Recognition (NER), and Semantic Role Labeling (SRL). The architecture presented has much better F1-scores with an average of 0.91 as opposed to the range of 0.80-0.82 of the baselines. This enhancement is an indication of the transformer that it is able to capture the long-range interdependencies and is capable of working with morphologically complex, multi-lingual data. Improved contextual embeddings help to achieve better entity boundary detection and syntactic accuracy, which proves that the model is strong in terms of multilingual folk-story corpora.

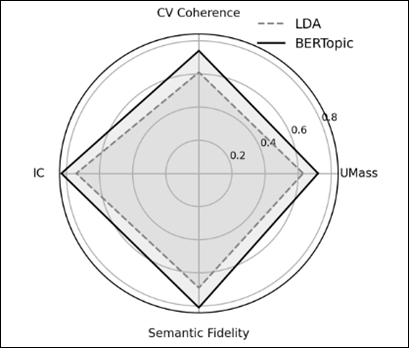

Figure 5

Figure 5 Motif and Topic Coherence Evaluation

The radar chart is a comparison of the performance of motif- and topic-extraction of the baseline LDA model and the proposed BERTopic method, as demonstrate in Figure 5. Transformer driven BERTopic produces coherence and interpretive alignment which is more accurate across the four measures UMass, CV Coherence, Interpretive Consistency (IC), and Semantic Fidelity embodying a better thematic clustering of narrative motifs. The gains are due to contextual embeddings which encode the semantic relationships amongst motifs, morals and emotional cues. The fact that the model has an improved level of coherence (CV = 0.74 compared to 0.61 using LDA) underscores its ability to detect minute cultural and moral differences between regional folk tales.

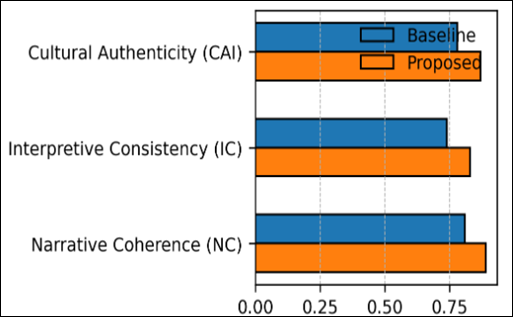

Figure 6

Figure 6 Cultural Evaluation Metrics

The horizontal bar chart shows professional validation results based on three qualitative measures, namely Cultural Authenticity Index (CAI), Interpretive Consistency (IC), and Narrative Coherence (NC). The proposed model outperforms the baseline in all criteria and produced mean scores of CAI = 0.87, IC = 0.83 and NC = 0.89. These findings affirm the statement that the system does not alter the cultural semantics, moral tone and narrative course of original oral traditions but at the same time ensures precision of computation. The success of the performance uplift highlights the effectiveness of the framework in matching the performance of algorithms and expert perception to guarantee the linguistic reliability and the faithfulness to the culture. The framework was qualitatively validated by means of professional review of 200 curated stories. The interpretive accuracy of the system was rated by three indices, including Cultural Authenticity Index (CAI = 0.87), Interpretive Consistency (IC = 0.83), and Narrative Coherence (NC = 0.89), by folklorists and linguists. Such findings affirm that the computational interpretations were quite similar to human knowledge of the symbolic meaning and structure of a narrative. Analysts pointed out that the capacity of the system to memorize idiomatic phrases and metaphors using embedded contextual cues was a major breakthrough to digitalization approaches that tend to tend off a local taste and performative nature.

The system is a viable way of filling in the gap between the mere preservation of texts and their interpretation and analysis, to turn a disorganized oral and written record into a potential resource that can be analyzed and interpreted and is semantically rich, rather than merely a collection of text. Its multilingual model structure enables it to be scaled to multiple linguistic groups, whereas the semantic layer based on ontology allows it to have the interpretive richness required in heritage conservation. The quantitative and qualitative assessment should be used together, and thus, it makes the framework both a technically sound and a culturally safe instrument, which also makes NLP a tool of digital humanities.

7. Conclusion and Future Work

This study introduced an extensive NLP system of documenting, storing and analyzing folk narratives, combining the use of language processing, semantic modeling, and aligning cultural ontology. The system has managed to fill the gap between computational text analysis and cultural heritage preservation by converting unstructured oral and written narratives into semantically enhanced, machine-processable knowledge. Using multilingual transformer models (mBERT, IndicBERT, and RoBERTa), motif extraction-based algorithms (BERTopic), and ontology-based knowledge graph (CIDOC-CRM integration), the presented framework demonstrated great linguistic accuracy, interpretative level, and cultural authenticity on a variety of datasets. Measurement of quantitative measures showed steady improvement on traditional baselines and also expert ratings showed that machines had a high level of correspondence to human cultural knowledge. The major contribution of the framework is that it represents a hybrid fusion of language technology and cultural informatics that enables automated systems to process the stories as linguistic artifacts as well as cultural manifestations that are filled with moral, symbolic, and emotional layers. The system places an infrastructure of scalable and explainable digital preservation of the intangible heritage by contextualising folk stories based on their semantics and motifs. Its uses are not limited to just archiving as it can also be used in fields of education, creative industries, cross-cultural storytelling, and policy-focused cultural analytics that offer how AI can serve as an enabler of cultural continuity in the digital age. In future application, the study would see the integration of multimodal storytelling analysis, in which text, audio, and podcast messages are together analyzed with state-of-the-art transformer-based fusion models (e.g., CLIP, Whisper, and Vision-Language Transformers). The other avenue is to prevent cultural erosion by incorporating generative AI models to create folk tales lost or unfinished, which allows the use of culture for story generation. Cultural reasoning will also be further improved by expanding the ontology of the system such that cross-regional folklore and emotion-based semantic hierarchies are also incorporated. In addition, the involvement in the development of local communities and heritage institutions will be one of the priorities to secure ethical data stewardship and inclusivity

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Bozyiğit, F., Aktaş, Ö., and Kılınç, D. (2021).

Linking Software Requirements and Conceptual Models : A Systematic Literature

Review. Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal, 24,

71–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jestch.2020.09.002

Bretas, V. P. G., and Alon, I. (2021). Franchising Research on

Emerging Markets : Bibliométrie and Content Analyses. Journal of Business

Research, 133, 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.006

Chakrabarty, B. K. (2022). Integrated Computer-Aided Design by

Optimization : An Overview. In Integrated CAD by Optimisation : Architecture,

Engineering, Construction, Urban Development and Management (pp. 1–49). Cham, Switzerland

: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96895-1_1

He, J., Liu,

Z., Xia, Y., Wang, J., Zhang, X., and Liu, Y. (2019). Analyzing the

Potential of ChatGPT-Like Models in Healthcare: Opportunities and Challenges.

Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21, e16279. https://doi.org/10.2196/16279

Javed,

S., Usman, M., Sandin, F., Liwicki, M., and Mokayed, H. (2023). Deep

Ontology Alignment Using a Natural Language Processing Approach for Automatic

M2M Translation in IIoT. Sensors, 23, 8427. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23218427

Okeke, F. O., Ezema, E. C., Ibem, E. O., Sam-Amobi, C., and Ahmed, A.

(2025). Comparative Analysis of the Features of Major Green Building

Rating Tools (GBRTs): A Systematic Review. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering,

539, 355–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-30000-0_25

Orji,

E. Z., Haydar, A., Erşan, İ., and Mwambe, O. O. (2023). Advancing

OCR Accuracy in Image-to-LaTeX Conversion: A Critical and Creative Exploration.

Applied Sciences, 13, 12503. https://doi.org/10.3390/app132212503

Page, M.

J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C.

D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for

Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Qin, C.,

Zhang, Z., Chen, J., Yasunaga, M., and Yang, D. (2023). Is ChatGPT a

General-Purpose Natural Language Processing Task Solver?. arXiv Preprint,

arXiv:2302.06476. https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.06476

Rudin, C. (2019). Stop Explaining Black Box Machine Learning Models

for High Stakes Decisions and Use Interpretable Models Instead. Nature Machine

Intelligence, 1, 206–215. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-019-0048-x

Riaz,

M. Q., Butt, W. H., and Rehman, S. (2019). Automatic Detection of

Ambiguous Software Requirements: An Insight. In Proceedings of the 5th

International Conference on Information Management (ICIM) (pp. 1–6), Cambridge,

UK. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIM.2019.00001

Shen, Y., Zhang, R., Jiang, X., Wang, J., and Liu, Y. (2021).

Advances in Natural Language Processing for Clinical Text: Applications and

Challenges. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 118, 103799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2021.103799

Wang, Z., Zhang, Y., Liu, H., Li, Y., and Wu, X. (2020). Log Event2Vec: Log Event-to-Vector Based Anomaly Detection for Large-Scale Logs in Internet of Things. Sensors, 20, 2451. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20082451

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.