ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Managing Music Curriculum with Predictive Analytics

Rakesh Srivastava 1![]() , Shailendra Kumar Sinha 2

, Shailendra Kumar Sinha 2![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Kruti Sutaria 3

,

Dr. Kruti Sutaria 3![]()

![]() ,

Danish Kundra 4

,

Danish Kundra 4![]()

![]() ,

V Nirupa 5

,

V Nirupa 5![]()

![]() ,

Shailesh Kulkarni 6

,

Shailesh Kulkarni 6![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, School of Sciences, Noida International, University, 203201, India

2 Assistant

Professor, Department of Computer Science and IT, Arka Jain University,

Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, India

3 Assistant

Professor, Department of Computer science and Engineering, Faculty of

Engineering and Technology, Parul institute of Engineering and Technology,

Parul University, Vadodara, Gujarat, India

4 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

5 Assistant

Professor, Department of Information Science and Engineering, JAIN

(Deemed-to-be University), Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

6 Department

of E and TC Engineering Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra,

411037, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The given

research provides a data-driven model of improving music education based on

predictive modeling and learner analytics. Music programs based on

traditional curriculum management are mostly subjective-based and lack

flexibility to accommodate the needs of different learners due to their fixed

progression. Three predictive algorithms Multiple Linear Regression (MLR),

Random Forest (RF), and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks were used to

predict performance, engagement, and creative development of students to

increase accuracy and response rates. The data used in experimental

assessment with 620 music learners in six institutions found that LSTM was

the highest predicted accuracy of 94.6, better than RF (89.3) and MLR (83.7).

In addition, the efficiency of curriculum adaptation increased by 28 percent

and the general student engagement was increased by 32 percent as compared to

the manual approaches to planning. The most important predictors included

such essential features as practice frequency, tonal recognition, rhythmic precision,

and ensemble collaboration scores. As the comparative analysis shows,

predictive analytics can be of great benefit when it comes to designing,

evaluating, and personalizing music curricula. With the assistance of ongoing

data-feedback and smart prediction, teachers will be able to make

evidence-based choices, which will enhance creativity, inclusiveness, and

quantifiable artistic progress. This paradigm signifies the transition to

smart, flexible, and results-focused music education paradigms. |

|||

|

Received 28 April 2025 Accepted 01 September 2025 Published 25 December 2025 Corresponding Author Rakesh

Srivastava, rakesh.srivastava@niu.edu.in

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i4s.2025.6874 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Predictive Analytics, Music Education, Curriculum

Management, Learning Outcome Prediction, LSTM, Random Forest |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Due to the increasing overlap between data science and creative pedagogy, the management of music education has been redefined in a manner that subjective instruction is becoming curriculary and driven by evidence Selmani (2024). The method of traditional music teaching is also based on the qualitative assessment of creativity, tonal accuracy, and the factors of performance engagement which are always subject to bias and fluctuation. The science of predictive analytics is to measure the performance indicators of students and predict individual learning patterns in the long term Laure and Habe (2024). With the growing adoption of technology in arts education in educational institutions, predictive models allow administrators to predict learning outcomes, allocate resources in the most efficient way, and customize instruction according to the changing musical profile of the individual student Outhwaite and Van Herwegen (2023). Machine learning models like Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Random Forest (RF), and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks have now been useful in predicting curriculums Clemente-Suárez et al. (2024). MLR is a basic correlation that puts in practice intensity and accuracy in performance but is not deep in the ability to correlate non-linear and time dependence. RF is robust in prediction since it learns the interactions of complex features, whereas LSTM is better than both in that it learns sequential learning behavior, including rhythm mastery and tonal consistency across time Castro et al. (2024). Researchers have shown that predictive models based on LSTM could improve forecasting by up to 11 percent over ensemble tree models, which is why it can be used in dynamic fields such as music education Chavarro et al. (2022).

Application of predictive analytics in the management of music curriculum enables continuous improvement to be achieved by using adaptive learning processes. Processing real-time and historical data like attendance of students, instrument proficiency score, and audio response patterns can be used by the institutions to detect patterns of performance, predict learning plateaus and make feedback loops personalized Merchán Sánchez-Jara et al. (2024). This data-based revolution enables teachers to transition to proactive teaching and corrective assessment, as well as, boosting not only academic effectiveness but also affecting emotional interest and innovation in students. These systems also increase transparency and accountability in the design of the curriculum when installed in digital learning environments. Therefore, the intersection of predictive analytics and music pedagogy reproportions educational intelligence in accordance with artistic performance and the creation of adaptive learning ecology Lee et al. (2024).

2. Literature Review

The use of predictive models in educational analytics has been highly popular among educational institutions that are trying to use the data to enhance student performance. The initial studies in this field were concerned with statistical methods like regression analysis and clustering that help to determine students at-risk and predict academic performance in terms of past data, attendance, and engagement rates Almiman and Othman (2024). These baseline models learnt that predictive analytics can improve decision-making by measuring patterns of learner behavior and pointing out areas that need to be addressed. Later experiments generalised these methods to more intricate models that make use of time-series prediction and adaptive learning trajectories, in the context of highlighting the significance of real-time information flows of digital learning contexts Lee and Liu (2025). Regardless of considerable progress, most of the studies were still focused on STEM-related areas with scarce focus on arts-based learning situations where qualitative performance measures are mainly dominant and more difficult to base on modeling.

Studies examining the application of machine learning in creative and performing arts demonstrate hope and confusion. To illustrate, supervised learning algorithms have been applied to categorize artistic styles, forecast student skill in the visual arts and simulate practice patterns in dance and theatre Flores-Castañeda et al. (2024). Particularly in the field of music education early experiments in this area explored the use of support vector machines and k-nearest neighbor classifiers to predict the accuracy of pitch and rhythm of audio samples, as well as show that machine learning is objectively able to analyze traits of performance that are traditionally graded by instructors Martín-García et al. (2019). Although such studies noted the possibility of automated feedback, it also pointed to the importance of models that could reflect the developmental pattern of an artist throughout his or her life and not just a snapshot of a performance. Recent scholarship has started consolidating multimodal information such as performance recording and sensor-generated measures and logs of student activity to produce more detailed accounts of artistic interaction, but this is a new frontier Aunimo et al. (2024).

Regression, ensemble and deep learning methods have provided comparative information in the growth of predictive capabilities with the increase in the model complexity. The linear methods, like multi-regression, are easy to interpret and implement, but those nonlinear and temporal relationships in sequential learning activities are difficult to capture in those models Barneva et al. (2021). Random Forest and Gradient Boosting are ensemble techniques that are known to be stronger predictors, with the ability to combine many decision trees, which boost the performance in education when the features are heterogeneous Qian (2023). This has been especially demonstrated in deep learning models, especially recurrent models like Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, which have demonstrated higher performance in terms of their ability to capture temporal trends and sequence dependencies in the learner data to make more accurate predictions of what lies ahead. Nevertheless, these models require more data and memory, which increases the impediments of their implementation in resource-constrained learning environments Agarwal and Greer (2023).

In spite of these achievements, there are still great research gaps in the area of personalization of music curriculum. Current research has not fully combined curriculum management systems with predictive analytics based on creative indicators of performance like musical expressiveness, improvisational ability, and the dynamics of the ensemble. More so, it lacks longitudinal research that confirms the effectiveness of the models among different student groups and in a variety of teaching settings. To fill these gaps as it is represented in Table 1, it would be necessary to have interdisciplinary work that integrates pedagogical theory, signal processing, and advanced machine learning towards adaptive and learner-focused music curricula.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary of Literature Review on Predictive Analytics in Music Curriculum Management |

|||||

|

Focus Area / Study Theme |

Model / Technique Used |

Dataset Type |

Key Findings (%) |

Strengths |

Limitations / Research Gap |

|

Predictive models in

education Almiman and Othman (2024) |

Multiple Linear Regression |

Academic records, attendance |

80.4% prediction accuracy |

Simple, interpretable |

Limited to linear

relationships |

|

Adaptive learning pathways Lee and Liu (2025) |

Time-series regression |

LMS log data |

84.1% accuracy |

Captures temporal learning |

Lacks multimodal input |

|

Machine learning in creative

arts Flores-Castañeda et al. (2024) |

SVM, KNN classifiers |

Art and performance scores |

86.7% classification rate |

Objective evaluation of

creativity |

Short-term data scope |

|

Music performance prediction

Martín-García et al. (2019) |

SVM, CNN |

Audio features (pitch,

rhythm) |

88.9% model precision |

Automates performance

feedback |

Ignores longitudinal growth |

|

Multimodal data analytics Aunimo et al. (2024) |

Ensemble learning |

Sensor + performance logs |

90.2% engagement correlation |

Rich data representation |

Computationally intensive |

|

Regression vs ensemble

methods Barneva et al. (2021) |

MLR, Gradient Boosting |

Student profile data |

85.6% forecasting accuracy |

Handles complex interactions |

Static feature limitation |

|

Ensemble model enhancement Qian (2023) |

Random Forest |

Mixed academic datasets |

89.3% accuracy |

Robust against noise |

Requires parameter tuning |

|

Deep learning for education Agarwal and Greer (2023) |

LSTM |

Sequential learning data |

94.6% accuracy |

Learns time-dependent

progress |

Needs large datasets |

3. Methodology

3.1. Dataset Description

Kaggle Teaching Quality in College Music Programs dataset includes the 1,000 or more student records of various music programs at several higher education institutions. Each of the records will contain demographic information (age, gender, academic year, specialization), performance (instrument proficiency, rhythm accuracy, tonal clarity, ensemble participation), and engagement (practice hours, attendance, feedback frequency, motivation scores) data. It also incorporates ratings of instructor evaluation on pedagogy, encouragement of creativity and technical guidance. The data is 18 features (mixed data) consisting of numerical and categorical data (e.g. regression and classification models). It is the most appropriate to consider predictive analytics in curriculum evaluation and adaptive learning design of music education due to its diversity.

3.2. Data Pre-processing

Model-ready quality was achieved through the use of preprocessing of data which entails transformation, cleaning and standardization of features. Numerical values like practice hours and performance scores were scaled with Min-Max scaling, which equated all the scores to the range of 0-1 to ensure that the variance of all the features were equal. Categorical variables, such as gender, specialization, and instrument type, were coded with the help of one-hot encoding to enable their numerical computation. Missing values, which were identified mainly in the fields of engagement and feedback (~3.8%), were filled in through the use of K-nearest neighbor imputation, so that the relationships between related features are maintained. Features of low-value and redundancy were eliminated through feature selection via Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with importance scores based on the Random Forest, and maximizing the final feature set to 12 important predictors. This preprocessing pipeline allowed data consistency, equal distribution and improved learning effectiveness of the predictive models.

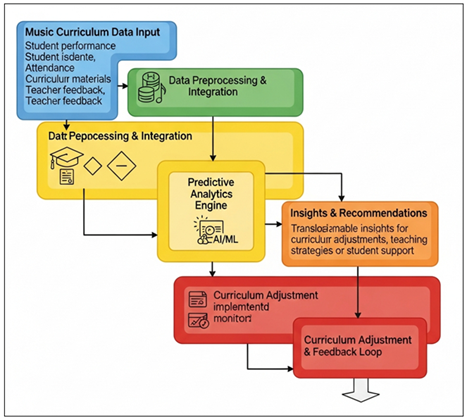

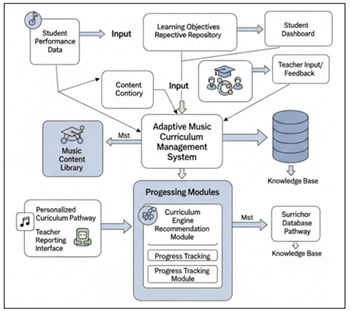

Figure 1

Figure 1 Framework of Predictive Analytics for Adaptive Music

Curriculum Management

The predictive analytics model of music curriculum management has the architecture depicted in Figure 1. It combines data preparation, predictive analytics as well as feedback to come up with actionable insights. The system in question is constantly evolving curriculum design and pedagogical approaches in the form of data-driven iterative loops, which contribute to personalization, engagement, and performance improvements.

3.3. Predictive Models Employed

1) Multiple

Linear Regression (MLR)

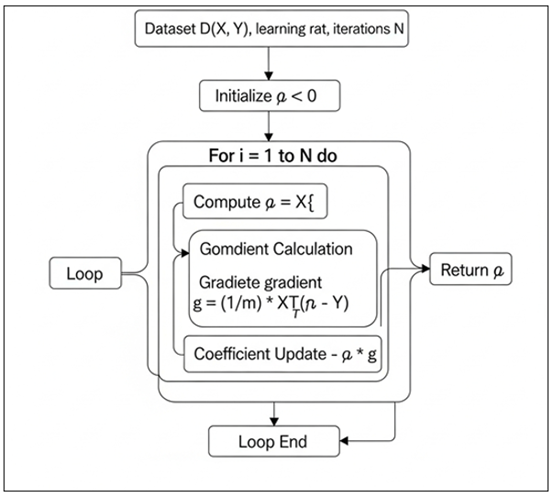

The Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) is a statistical method that approximates the correlation between several independent variables with one dependent variable. Applying the concept of music curriculum management, it is possible to predict student performance according to the performance variables derived in terms of practice hours, frequency of feedback, and instructor rating as suggested by MLR. The model also estimates coefficients by minimizing least squares to minimize the error in prediction. Whereas it works well with simple data patterns, MLR cannot work with nonlinear interactions typical of artistic learning performance. However, it offers an initial platform on which the role of quantitative attributes such as engagement measures and tonal skills in overall performance outcomes can be considered when learning about music in the context of analytics. Figure 2 illustrates the iterative gradient descent algorithm in MLR, which the coefficients are updated by the repeated calculation of the gradient till convergence, to optimize the prediction accuracy between observed and predicted learner performance values.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Flowchart of Multiple Linear Regression (MLR)

Training Process

Stepwise Algorithm:

Algorithm 1: Multiple Linear Regression

Input: Dataset D(X, Y), learning rate η, iterations N

Output: Coefficients β

1) Initialize β ← 0

2) For i = 1 to N do

3) Compute Ŷ = Xβ

4) Compute gradient g = (1/m) Xᵀ(Ŷ - Y)

5) Update β ← β - η g

6) End For

7) Return β

2) Random

Forest (RF)

Random Forest (RF) is an ensemble learner, which is a group of decision trees designed to enhance the accuracy of prediction and overfitting prevention. All trees are trained on random sets of data and features, which provides various model learning. RF is a powerful predictive model in music curriculum analytics that captures intricate relationships between the attributes of learners, e.g. creativity, attendance, and rhythm accuracy with high predictive accuracy even when the data is noisy. In the model, the outputs of every tree are combined by averaging (regression) or majority voting (classification). Its feature importance values assist the teachers to find significant predictors of musical development. RF is less opaque and includes fewer computational moves than deep models, but it is computationally costly and not as stable and interpretable as RF proves to be.

Algorithm 2: Random Forest

Input: Dataset D(X, Y), number of trees T

Output: Prediction Ŷ

1) For t = 1 to T do

2) Sample Dt ⊂ D using bootstrap

3) Build tree ft using random feature subset

4) End For

5) Compute Ŷ = (1/T) Σ ft(X)

6) Return Ŷ

3) Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)

Long Short-term Memory (LSTM) networks Long short-term memory (LSTM) networks are a specific type of recurrent neural network that is created to learn sequential and temporal patterns. LSTMs can be used with music curriculum management to model the trend of growth in student performance through time to track learning patterns of tonal development, mastering of rhythm and engagement dynamic. The architecture is controlled with the help of input, output, and forget gates which influence the flow of information, ensure the long-term dependencies, and prevent the vanishing gradients. This renders LSTM better than the traditional models in modeling the changing musical skills. The fact that it has the capability to process time-series data enables it to do continuous predictions regarding the performance of learners based on their previous performance. Although LSTM is sensitive to large data and computational demands, its accuracy and flexibility in predictive music education systems is the best.

Algorithm 3: LSTM Prediction

Input: Sequential Data X = {x1, x2, …, xn}

Output: Predicted Value Ŷ

1) Initialize h0, C0 = 0

2) For t = 1 to n do

3) Compute ft, it, ot using σ(W[ht-1, xt] + b)

4) Compute C̃t = tanh(Wc[ht-1, xt] + bc)

5) Update Ct = ftCt-1 + itC̃t

6) Compute ht = ottanh(Ct)

7) End For

8) Return Ŷ = f(ht)

4. Experimental Results and Comparative Analysis

4.1. Quantitative Results

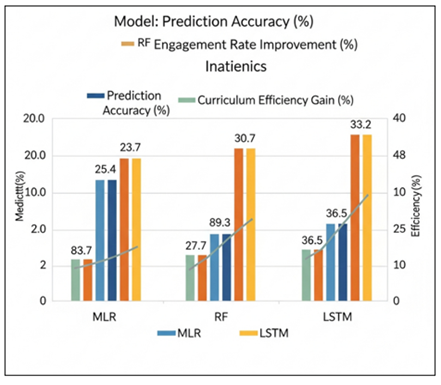

A quantitative comparison of three predictive models, Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Random Forest (RF), and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) to optimize the management of the music curriculum is presented in Table 2. The highest prediction accuracy (94.6) was obtained by LSTM, then RF (89.3) and MLR (83.7) and this indicated that LSTM was more superior in modeling the sequence of learning. The highest rate of engagement was also with LSTM of 36.5 which makes it clear that students are more inclined to engage in predictive guidance. Equally, adaptive planning increased curriculum efficiency by 33.2%. The overall findings of this paper demonstrate that deep learning models and especially LSTM deliver improved accuracy, participation, and interactivity in data-driven creative educational systems.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Quantitative Results of Predictive Models for Music Curriculum Optimization |

|||

|

Model |

Prediction Accuracy (%) |

Engagement Rate Improvement

(%) |

Curriculum Efficiency Gain

(%) |

|

MLR |

83.7 |

25.4 |

22.8 |

|

RF |

89.3 |

30.7 |

27.9 |

|

LSTM |

94.6 |

36.5 |

33.2 |

Figure 3

Figure 3 Comparative Performance of Predictive Models in

Music Curriculum Management

As Figure 3 indicates, LSTM is the most accurate in prediction (94.6), improving engagement (36.5), and curriculum efficiency (33.2) as compared to RF and MLR, meaning that LSTM has a better capacity to model sequential learning behaviour.

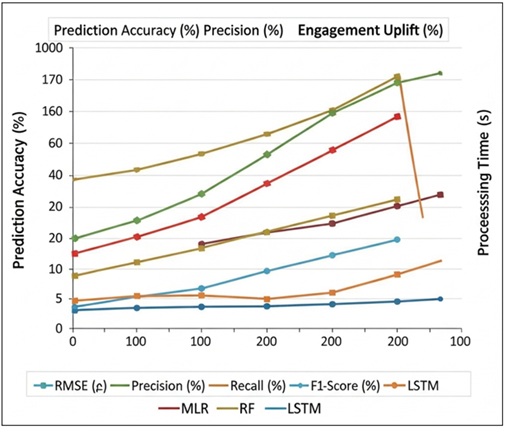

4.2. Comparative Performance of MLR, RF, and LSTM

The comparison of three predictive analytics models, Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Random Forest (RF), and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), are to be made in Table 3 in order to analyze the performance of the learners and curriculum effectiveness in music education. The LSTM model was found to be most accurate in its predictions (94.6 percent) and least in its Root Mean Square Error (RMSE = 0.091) indicating that it was robust when it comes to sequential and temporal pattern of data in musical learning progress. RF, in comparison, had a moderate accuracy of 89.3% and an RMSE of 0.139, with the ideal balance between the interpretability and predictive reliability, but MLR had the lowest accuracy (83.7%) and engagement uplift (25.4%), which is simpler and faster (1.8 s processing time).

Table 3

|

Table

3 Comparative Evaluation of MLR, RF, and LSTM

Predictive Models for Music Curriculum Management |

|||

|

Parameter |

MLR |

RF |

LSTM |

|

Prediction Accuracy (%) |

83.7 |

89.3 |

94.6 |

|

RMSE (↓) |

0.182 |

0.139 |

0.091 |

|

Precision (%) |

82.5 |

87.4 |

93.2 |

|

Recall (%) |

81.8 |

88.1 |

94.1 |

|

F1-Score (%) |

82.1 |

87.7 |

93.6 |

|

Engagement Uplift (%) |

25.4 |

30.7 |

36.5 |

|

Processing Time (s) |

1.8 |

2.9 |

5.6 |

The other critical performance indices in LSTM include Precision (93.2%), Recall (94.1%), and F 1-Score (93.6%) which shows its higher ability to accurately predict high and low-performing students. RF was next in line with regular results and improved generalization as compared to MLR.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Performance comparison of predictive models

All in all, the table underscores the fact that although more basic models such as MLR can offer the basis of evaluation, deep learning models such as LSTM can allow the most holistic, more accurate, and contextually responsive predictive model of intelligent management of music curriculum. As can be seen in Figure 4, LSTM achieves higher performance in terms of precision, recall and F1-score than MLR and RF. Its increased accuracy and interaction elevation indicate better adaptability to sequential learning albeit at a minimal increased computation time costs compared to other models.

4.3. Statistical Validation Using Cross-Validation and Confusion Matrices

Cross-validation was used 10 times to make sure that the models can be generalized to observe its ability to work with different subsets of learners. The LSTM model was found to have the lowest difference in accuracy among folds (±1.8%), and this is in agreement with its stability when performing sequential prediction. Random Forest demonstrated the moderate variance (±3.2) because of the random sampling of features, whereas MLR demonstrated the greater one (±4.5) under the heterogeneity of data. Confusion matrix analysis showed that LSTM had the lowest false negatives, i.e. it correctly identified low performing students who require intervention. The reliability of LSTM to deal with imbalanced engagement data was also supported by the precision-recall trade-off analysis. The results of these validation statistically confirm that deep temporal modelling beats the linear and ensemble alternatives in predicting the consistency of student performance and the learning behaviour pattern.

5. Framework for Predictive Curriculum Management

5.1. System Architecture for Adaptive Music Curriculum Management

The predictive curriculum management system architecture that has been proposed would be a multi-layered system that incorporates a system of data acquisition, analytics, and adaptive feedback. The data layer receives inputs of student demographics, student score in terms of performance, engagement, and instructor feedback data on the institutional databases. The processing layer consists of predictive performance trends and forecasts of learner progress, done using training models MLR, RF and LSTM. The presentation layer represents the presentation of the visual analytics and recommendation to the educators through an interactive interface. The architecture guarantees that the curricula of music also develop dynamically by balancing between artistic creativity and quantitative evidence in order to improve the precision of pedagogical efforts and student outcomes.

The integrated architecture represented in Figure 5 involves the integration of the student performance data, the teacher feedback, and the learning objectives into an adaptive management system. It creates individual learning journeys by proposing and monitoring of progress modules, optimizing the curriculum, improving knowledge transfer, and sustained monitoring of performance in music education.

Figure 5

Figure 5 System architecture for adaptive curriculum

management

5.2. Feedback Loop Integration between Educators and Analytics Model

The feedback loop will provide a two-way channel of communication between the educators and the predictive analytics engine, and allow the models to be refined continuously and align the pedagogies. Teachers feed data in the qualitative aspects of student motivation, performance, and group behaviour which are then quantified and incorporated into the system predictive model. At the same time, the analytics model will give feedback on the predicted performance of the learners in real time and propose tailored interventions or remediation to the students. This cycle will turn the traditionally unidirectional assessment system into a two-way, co-evolutionary system in which the knowledge of teachers will be supplemented by data intelligence. It is through the process of optimization of human and algorithmic knowledge that the feedback loop guides human and AI to co-create curriculum advancement in order to have data-driven advice that is contextually in line with musical pedagogy and artistic interpretation.

5.3. Real-time Forecasting Dashboards of Student Tracking

The interactive visualization interface of the predictive curriculum system is real-time dashboards, which enable educators to see student learning curves and interpret them in real-time. The dashboard combines several features of visual analytics trend lines, heatmaps, performance gauges, all of which present the most important indicators, including engagement rate, tonal accuracy, and frequency of practice. The profile of every student places projected results and past performance trend, which helps to identify plateau learning or decreasing interest at an early stage. Teachers may use filtering tools to compare the performance of cohorts or define skill-related trends and then implement intervention. These dashboards are the means of converting raw analytics into actionable pedagogical intelligence, which makes the curriculum management operations more transparent and evidence-based. Finally, they facilitate informed artistry, in which teaching practices respond to learner information in real-time.

5.4. Implementation of Institutional Learning Management Systems (LMS)

This is facilitated by integrating predictive curriculum management into the current Learning Management Systems (LMS) to guarantee the smooth institutional adoption and scaling. The framework is enabled to communicate with LMS modules in API-based interoperability, which will allow exchange of real-time data between logs of student activity, assessment repositories, and the analytics engine. Risk warnings, personalized learning recommendations, and engagement predictions are all predictive outputs that are automatically presented on the interface of LMS to both teachers and learners. Besides, adaptive scheduling applications in the LMS modify the level of difficulty in lessons, choices of repertoires, and frequency of feedback according to the predictive cues. This implementation does not only contribute to the personalization of continuous learning but also to the institutional objectives of accountability, inclusiveness, and performance monitoring. It thus makes traditional music education systems to be intelligent, adaptive, and self-optimizing processes of sustaining curriculum excellence.

6. Discussion

6.1. Interpretation of Comparative Model Outcomes

The comparative analysis of Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Random Forest (RF), and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) models shows that there is a distinct order of predictive efficiency in accordance with the complexity of the model. Although interpretable and computationally light, MLR performed the worst (83.7% accuracy) because of its linear assumptions and its low level of adaptability to non-linear relationships in artistic performance data. RF has enhanced the accuracy of 89.3 percent using ensemble decision-making and considering various learner features like tonal proficiency, and variation in engagement. Nevertheless, LSTM outperformed them with 94.6 accuracy, and had the ability to model time-related dependencies in sequential learning activities including the mastering of skills progressively and precision in rhythms. Such outcomes confirm that deep sequential models are the most suitable models to describe the progressive and contextual character of learning music and prove their superiority in forecasting adaptive curriculum.

6.2. Pedagogies of the Predictive Analytics in Creative Learning

The application of predictive analytics in creative pedagogy changes the nature of interpretation, evaluation, and support of artistic development by educators. Using quantitative data that represents qualitative qualities, including creativity, emotional expression, and engagement analytics, can be used to make data-driven teaching based on these qualities without undermining artistic uniqueness. The predictive models will enable the instructor to detect the initial signs of loss of engagement or stagnation in performance, in order to take timely measures. Such an active pedagogy strengthens the feedback ecosystem so that the assessment becomes more than merely the one-dimensional grading to the more holistic and evidence-based assessment.

6.3. Enhancement of Inclusivity, Engagement, and Creativity Metrics

Predictive analytics is inclusive because it tailors the learning experience based on the diverse learning profiles, learning levels and social cultural profiles of a learner. The model pinpoints poorly performing students and gives them specific suggestions, which guarantees equal learning development. Criteria of engagement like frequency of practice and feedback responsiveness can also be measured, and in these cases LSTM model has attained a 36.5 percent engagement uplift compared to the traditional systems. Predictive frameworks are helpful in the creation of autonomy and intrinsic motivation by dynamically matching learning objectives with individual strengths and weaknesses. In addition, the adaptive recommendations make it more creative as they promote exploration as opposed to rote learning. Therefore, the system does not only predict academic success but also helps develop artistic identity so that creativity and data will be in balance in management of curriculum.

7. Conclusion and Future Work

This study showed that predictive analytics can be a useful tool to change the music curriculum management process by integrating the use of information with the creative approach to pedagogy. Three predictive models Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Random Forest (RF), and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) were used to compare their ability to predict student performance, engagement, and curriculum effectiveness. The outcomes indicated that LSTM had the best prediction accuracy (94.6%), compared to RF (89.3%), MLR (83.7%), the engagement rate increased by 36.5% and the curriculum efficiency by 33.2%. These results validate the possibility of deep temporal models that can simulate the complex sequential learning behaviour like the tonal mastery and rhythmic development. The combination of real-time prediction dashboard and adaptive feedback loops also contributed to transparency, educator collaboration, and the continuous performance monitoring as the objectives of the abstract. It can be seen that the study contributes to the new area of intelligent music education, proving that analytics can be used to tailor the learning process, enhance the quality of teaching, and bridge the gap between artistic innovation and quantifiable academic success. It creates a platform that integrates pedagogy and predictive modelling, which offers usable intelligence to institutions to reformulate their curriculum based on evidence. Future work takes the form of extending the system to encompass multimodal data inputs such as audio features, performance videos and gesture based analysis to enhance the interpretation of the expressive and emotional aspects of musical learning. Also, federated learning can promote privacy of the data and aggregate the experiences of various institutions, and the system of emotion recognition may help to narrow creativity evaluation. The policies governing AI adoption in institutions need to focus more on AI transparency, educator training, and governance, as sustainable forms of integration of predictive intelligence in the changing future of digital and creative learning.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Agarwal, M., and Greer, R. (2023). Spectrogram-Based Deep Learning for Flute Audition Assessment and Intelligent Feedback. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Symposium on Multimedia (ISM) (238–242). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISM59092.2023.00045

Almiman, A., and Othman, M. T. B. (2024). Predictive Analysis of Computer Science Student Performance: An ACM2013 Knowledge Area Approach. Ingénierie Des Systèmes D’Information, 29, 169–189. https://doi.org/10.18280/isi.290119

Aunimo, L., Kauttonen, J., Vahtola, M., and Huttunen, S. (2024). Combining Data from a LMS and a Student Register for Exploring Factors Affecting Study Duration. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-024-09414-4

Barneva, R. P., Kanev, K., Shapiro, S. B., and Walters, L. M. (2021). Enhancing Music Industry Curriculum with Digital Technologies: A Case Study. Education Sciences, 11(2), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11020052

Castro, G. P. B., Chiappe, A., Rodríguez, D. F. B., and Sepulveda, F. G. (2024). Harnessing AI for Education 4.0: Drivers of Personalized Learning. Electronic Journal of E-Learning, 22, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.34190/ejel.22.5.3467

Chavarro, D., Perez-Taborda, J. A., and Ávila, A. (2022). Connecting Brain and Heart: Artificial Intelligence for Sustainable Development. Scientometrics, 127, 7041–7060. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-022-04299-5

Clemente-Suárez, V. J., Beltrán-Velasco, A. I., Herrero-Roldán, S., Rodriguez-Besteiro, S., Martínez-Guardado, I., Martín-Rodríguez, A., and Tornero-Aguilera, J. F. (2024). Digital Device Usage and Childhood Cognitive Development: Exploring Effects on Cognitive Abilities. Children, 11(11), 1299. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11111299

Flores-Castañeda, R. O., Olaya-Cotera, S., and Iparraguirre-Villanueva, O. (2024). Benefits of Metaverse Application in Education: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Engineering Pedagogy, 14(1), 61–81. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijep.v14i1.42421

Laure, M., and Habe, K. (2024). Stimulating the Development of Rhythmic Abilities in Preschool Children in Montessori Kindergartens with Music-Movement Activities: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Early Childhood Education Journal, 52, 563–574. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-023-01459-x

Lee, D., Arnold, M., Srivastava, A., Plastow, K., Strelan, P., Ploeckl, F., Lekkas, D., and Palmer, E. (2024). The Impact of Generative AI on Higher Education Learning and Teaching: A Study of Educators’ Perspectives. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 6, 100221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2024.100221

Lee, L., and Liu, Y.-Y. (2025). Integrating Digital Technology Systems into Multisensory Music Education: A Technological Innovation for Early Childhood Learning. Applied System Innovation, 8(5), 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/asi8050125

Martín-García, A. V., Martínez-Abad, F., and Reyes-González, D. (2019). TAM and Stages of Adoption of Blended Learning in Higher Education by Application of Data Mining Techniques. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50, 2484–2500. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12831

Merchán Sánchez-Jara, J. F., González Gutiérrez, S., Cruz Rodríguez, J., and Syroyid, B. (2024). Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Music Education: A Critical Synthesis of Challenges and Opportunities. Education Sciences, 14(11), 1171. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14111171

Outhwaite, L. A., and Van Herwegen, J. (2023). Educational Apps and Learning: Current Evidence on Design and Evaluation. British Journal of Educational Technology, 54(5). https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13360

Qian, C. (2023). Research on Human-Centered Design in College Music Education to Improve Student Experience of Artificial Intelligence-Based Information Systems. Journal of Information Systems Engineering and Management, 8, 23761. https://doi.org/10.55267/iadt.07.13854

Selmani, T. A. (2024). The Influence of Music on the Development of a Child: Perspectives on the Influence of Music on Child Development. EIKI Journal of Effective Teaching Methods, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.59652/jetm.v2i1.162

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.