ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Augmented Reality in Media-Based Learning Environments

Kunal Dhaku

Jadhav 1![]() , Poonguzhali S 2

, Poonguzhali S 2![]()

![]() ,

Prachi Rashmi 3

,

Prachi Rashmi 3![]()

![]() ,

Tapasmini Sahoo 4

,

Tapasmini Sahoo 4![]()

![]() ,

Yasoda Ramesh 5

,

Yasoda Ramesh 5![]()

![]() , Sachin Mittal 6

, Sachin Mittal 6![]()

![]() ,

Om Prakash 7

,

Om Prakash 7![]() , Ashutosh Kulkarni 8

, Ashutosh Kulkarni 8![]()

1 Lifelong

Learning and Extension, University of Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

2 Professor,

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Aarupadai

Veedu Institute of Technology, Vinayaka Mission’s Research Foundation (DU),

Tamil Nadu, India

3 Greater

Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201306, India

4 Associate

Professor, Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering, Siksha 'O' Anusandhan (Deemed to be University), Bhubaneswar, Odisha,

India

5 Assistant

Professor, Department of Fashion Design, Parul Institute of Design, Parul

University, Vadodara, Gujarat, India

6 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

7 Associate

Professor, School of Business Management, Noida international University

8 Department

of DESH Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Augmented

Reality (AR) has become a revolutionary technology in the educational field,

and it fills the gap between the physical and the digital learning

environment. This paper describes the application of AR to the learning

context using media, with a focus on its ability to improve interactivity,

immersion, and contextual learning. AR promotes both constructivist and

experiential learning methods by integrating multimedia elements like text,

audio, video and 3D objects into real-life contexts which enables learners to

adopt complex concepts through their visualization and manipulation. The

paper has laid down a theoretical basis based on multimedia learning and

cognitive load theory, and so, the AR-based interactions are not overly

engaging or mental consuming. An extensive system architecture is presented,

which includes the description of hardware-software ecosystem, content

pipeline, and UX/UI design of educational AR applications. The research

design involves experimental validity on the platform of Unity, ARKit, and ARCore, and the analysis of participants on the

background of retention of learning, motivation, and spatial cognition.

Findings show that there is considerable enhancement in the level of

conceptual knowledge as well as learner involvement in the occasion of the

incorporation of AR in the media enriched lesson plans. Scalability,

compatibility of devices, and accessibility have been identified as

challenges in the discussion, whereas the future is based on AI-driven

personalization, cloud deployment, and gamified collaboration. The paper adds

to the developing debate on immersive learning, making AR one of the main

facilitators of adaptive, interactive, and inclusive learning. |

|||

|

Received 01 April 2025 Accepted 06 August 2025 Published 25 December 2025 Corresponding Author Kunal Dhaku Jadhav, jdkunal@mu.ac.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i4s.2025.6870 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Augmented

Reality, Media-Based Learning, Experiential Learning, Educational Technology,

Interactive Pedagogy, Immersive Education |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Overview of Augmented Reality (AR) and its evolution in education

Augmented

Reality (AR) is a dynamic technological innovation, which superimposes digital

content (images, animations, 3D models) on the physical one in real time. The

state of development of AR in the field of education has shifted to the

application of experimental visualization devices to more powerful pedagogical

tools that can create an immersion in the learning process. Early AR art in

education became present with markers-based systems that allow the simple

recognition of objects, and the current AR platforms (ARKit, ARCore, and Unity) have added features of spatial mapping,

gesture recognition as well as adaptable content generation. The incorporation

of AR is in line with the general paradigm of Industry 4.0, and Education 5.0,

which supports experiential, personalized, and learner-centered

learning. AR can help students to engage with virtual scenarios, historic

recreations, or complicated scientific processes by combining real with virtual

worlds, thereby improving the level of conceptual or memorization knowledge Fombona-Pascual et al. (2022). Additionally, AR promotes

multimodal learning because it uses visual, auditory, and kinesthetic

learning, resulting in higher forms of thinking. The future of AR in education

can be described as moving towards the use of artificial intelligence

(AI)-based personalization, adaptive systems that are able to detect their

surroundings, and virtual co-locations that overcome the geographical

differences. With the growing digitalization and immersiveness

of education, AR can be viewed as a major linkage between the abstract and

practical, as learners have the ability to explore,

manipulate, and visualize information in meaningful and interactive ways Marín et al. (2022).

1.2. Definition and Scope of Media-Based Learning Environments

The

media-based learning environment (MBLEs) refers to the instructional

environments in which a wide range of digital media such as text, audio, video,

graphics, simulations, interactive modules etc. are combined to facilitate

multiple learning modalities. In comparison to the conventional classes, which

mostly depend on the linear delivery of information, the MBLEs offer nonlinear,

multi-modal, and learner-oriented experience that facilitates learning and

involvement Karacan and Polat (2022). They are digital tool-based,

content management-based, and visualization, environments, which make use of

exploration and collaboration to build knowledge in an interactive environment.

The scope of MBLEs runs both in formal education, corporate training, and

informal learning settings and is aided by technologies of virtual reality

(VR), AR, and mixed reality (MR). In educational systems, MBLEs facilitate

adaptive learning processes in which the content can be dynamically adjusted to

the profile of the learner, their cognitive preferences, as well as real-time

feedback systems Hobbs and Holley (2022). Multimedia convergence enables

them to participate in inquiry-based learning, experimentation by simulation,

and storytelling.

1.3. Significance of Integrating AR into Media-Rich Educational Contexts

Incorporation

of Augmented Reality (AR) in media rich education can transform learning by

engaging in interactivity, immersion and contextual relevance. AR takes

conventional multimedia learning one step further to incorporate digital

objects (3D models, animations and videos, data visualization) into the

physical space of the learner and change the aspect of passive consumption of

the content into the one of active engagement.

This

multi-modality integration is congruent with the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia

Learning by Mayer in which it is claimed that learners build greater

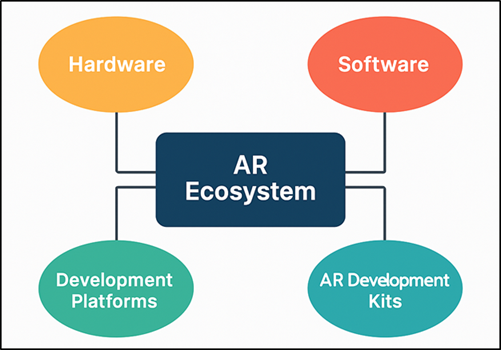

comprehension based on a coordinated input of the senses. Figure 1 demonstrates that core

dimensions of the AR are helping to increase the learning in media-rich

learning. AR is a facilitator of experiential learning in media-based contexts

to help students learn about abstract scientific processes in a way that allows

manipulation of virtual artifacts or allows them to explore historical contexts

as part of their own space. The pedagogical importance is in its ability to

increase spatial cognition, problem-solving skills, and conceptual memory with

the help of the hands-on interaction Lim (2022). Additionally, AR encourages

cooperative learning because it enables two or more users to interact with

common virtual elements which encourages communication and collaboration. Its

dynamic flexibility also promotes differentiated instruction in which students

get personalized feedback and assignments on the basis of performance

analytics.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Core Dimensions of AR Integration within Media-Rich

Educational Contexts

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Constructivist and experiential learning frameworks

Augmented

Reality (AR)-based education is based on the constructivist and experiential

learning models. These frameworks are based on the theories of Piaget,

Vygotsky, and Dewey and hold that knowledge building occurs through active

interaction, reflective and contextual exchange as opposed to passive

absorption. AR inherently is in line with the principles of constructivism,

placing learners in interactive, problem-based spaces, where abstract concepts

have a base in the real world Erçağ and Yasakcı

(2022). AR provides real learning

activities that stimulate exploration, hypothesis testing and feedback through

visual overlay and spatially related simulation. According to Kolb,

experiential learning focuses on the process of concrete experience, reflective

observation, abstract conceptualization and active experimentation. AR makes it

possible through this cycle so that learners can interact with the phenomena

itself, such as visualizing molecular structures or recreating historical

locations, and reflecting on the experience of that interaction in a digital or

collaborative environment Andrews (2022). In addition, AR enhances

social constructivism, through encouraging cooperative communication and mutual

manipulation of online artifacts. This follows the Zone of Proximal Development

as proposed by Vygotsky in which the knowledge is co-constructed with the help

of peers or the instructor.

2.2. Multimedia Learning Theory and Cognitive Load Considerations

The

application of AR in learning processes that are mediated by media is based on

the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning presented by Richard Mayer,

according to which the cognitive activity is the most productive when

information is conveyed both visually and orally. AR environments are biased

towards these dual channel processing and combine text, images, sounds, and 3D

models that learners can interact with in order to construct meaningful mental

representations. Nonetheless, these deep multimodal experiences also create the

challenge of cognitive load, with the overload of working memory potentially

being a problem when stimuli are too many Drljević et al. (2022). Cognitive Load Theory Sweller proposed this theory which classifies mental effort

as intrinsic, extraneous and germane load. The design in AR based learning

should therefore strike a balance between these factors whereby the extraneous

factors are minimized and the germane load increased to facilitate the

development of the schema. As an example, spatially contextualized annotations

or guided overlays can minimize the cognitive fragmentation, and adaptive AR

interfaces can provide a personalized experience to the capacity of a

particular learner. Besides, multimedia coherence, redundancy and signaling principles should be well used to keep attention

and clarity Dutta et al. (2022). AR applied in its appropriate

manner to multimedia learning serves as an addition of conceptual to embodied

cognition in which the learner can physically experience and manipulate digital

information.

2.3. Interaction Design Principles in AR-Based Pedagogy

The

interaction design in AR-based pedagogy is concerned with designing friendly,

meaningful, and pedagogically oriented user experiences that enable the active

engagement and learning. A proper AR interaction design closes the gap between

usability and didacticism, making the technology positively contribute to the

learning goals and objectives instead of being distracting. The interface

development is informed by core principles of affordance, feedback, consistency

and minimal cognitive friction and facilitated by multimodal interaction which

integrates gesture/ voice/ gaze and allows a user to interact with the

interface in natural mode Lampropoulos et al. (2022), Díaz et al. (2023). Pedagogically, interaction

design has to be consistent with experiential and constructivist learning,

allowing the learner to discover, play with, and co-author knowledge in

spatially augmented space. Following the example of touch-based interaction on

virtual models in an anatomy course or gesture-based interaction in engineering

simulations, embodied cognition can be encouraged, with learning developed

through direct interaction of the two Fearn and Hook (2023). Table 1 is a summary of previous AR

learning research, including methods, contributions and limitations. Also,

visual cues, haptic reactions, and real-time performance metrics, which are

adaptive feedback mechanisms, improve motivation and self-regulation. AR also

requires interaction design to consider accessibility that will make it

inclusive to learners with various disabilities.

Table 1

|

Table

1 Related

Work Summary on Augmented Reality in Media-Based Learning Environments |

||||

|

Study

Focus |

AR

Platform/Tool Used |

Learning

Domain |

Evaluation

Metric(s) |

Key

Findings |

|

Interactive AR learning

experiences |

ARToolkit |

STEM Education |

Engagement, Comprehension |

AR increased conceptual

clarity and enjoyment |

|

Mobile AR for science

visualization |

Unity + Vuforia |

Physics |

Knowledge Gain, Retention |

Improved visualization and

spatial reasoning |

|

AR impact on motivation and

attitude De la Plata et

al. (2023) |

ARCore |

General Education |

Motivation Index, Retention |

Increased motivation and

learning persistence |

|

Collaborative AR learning

environments |

ARKit |

Engineering Design |

Task Accuracy, Collaboration |

AR improved teamwork and

design accuracy |

|

AR for cognitive skill

enhancement |

Unity3D |

Biology |

Cognitive Load, Focus |

Lowered cognitive load and

improved retention |

|

AR storytelling for creative

learning |

Spark AR |

Media Studies |

Creativity, Engagement |

Enhanced narrative

expression and creativity |

|

Spatial learning in AR

classrooms |

ARCore +

Unity |

Geography |

Spatial Memory, Achievement |

AR improved retention of

spatial data |

|

Gamified AR learning Taggart et al.

(2023) |

Unity + ARKit |

Computer Science |

Motivation, Performance |

Gamified AR boosted

engagement and grades |

|

AR-supported lab simulations |

Vuforia |

Chemistry |

Conceptual Understanding |

Higher accuracy in

experiment interpretation |

|

Cognitive impact of

immersive AR |

Unreal Engine |

Psychology |

Cognitive Engagement, Focus |

Improved attention span and

deep learning |

3. System Architecture and Design

3.1. AR hardware and software ecosystem

AR

hardware-software ecosystem is the technological foundation of the system

facilitating the immersion of the educational experience. The current AR

systems are based on a combination of sensors, processors, and rendering

engines to help one interact with the digital and real worlds in a real-time.

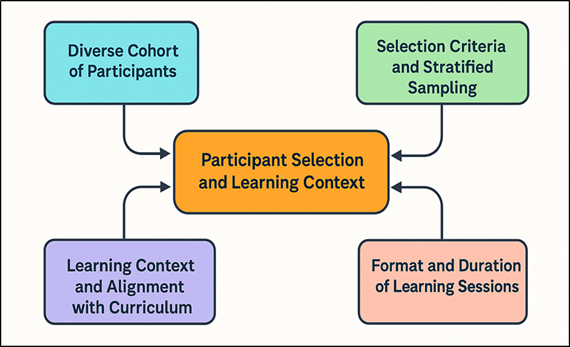

Figure 2

Figure 2 Components of an Augmented Reality (AR) Hardware and Software Ecosystem

Hardware

On the hardware front, users can use devices as small as handheld mobile

platforms and tablets or head-mounted displays (HMDs), including Microsoft

HoloLens, Magic Leap, and Meta Quest, with different levels of immersion,

spatial tracking, and portability. In Figure 2, there are essential AR

hardware-software elements that provide the means of smooth interactive

learning. The key elements are depth sensors, RGB cameras, accelerators, and

gyroscopes that take images of the space and motion of the user. The software

layer incorporates AR development systems such as Unity3D, Unreal Engine, ARKit

(Apple), ARCore (Google), and Vuforia that present

the required APIs to serve the purpose of object recognition, environment

mapping, and 3D rendering.

3.2. Media Integration Workflow

AR-based

educational design revolves around the media integration workflow, which allows

combining multimodal components (text, audio, video, and 3D content) with a

coherent and interactive learning experience. The given workflow starts with

the content design phase, at which learning objectives are correlated with

specific types of media so that to guarantee pedagogical compatibility. To give

an example, textual notes can be used to provide some conceptual details, audio

narratives can be used to help engage with the language more actively, and

videos and 3D models can be used to visualize complex phenomena dynamically.

Development entails bringing these elements in and aligning them in development

platforms of AR like Unity or Unreal Engine. Such techniques as a texture

mapping, spatial anchoring, and animation scripting help to place the content

in the context of the environment of the learner. Also

it has interactive triggers like touch, voice or recognition of gestures mean

to enable the learner to control the flow of information. The rendering and

optimization step aims at eliminating latency and providing smooth integration

between devices and the state of lighting.

4. Methodology

4.1. Research design and experimental setup

The

study design to assess Augmented Reality (AR) in media-based learning

classrooms is a mixed-method design, which combines both quantitative and

qualitative research design to provide holistic understanding of the teaching

and learning effectiveness. The experimental design is pretest/ posttest control group, in which one group of participants

will use AR-enhanced media modules and another group

will be under control (so they will be exposed to normal multimedia

instruction). It aims at the evaluation of quantifiable variance in the

learning outcomes, engagement rates, and cognitive retention. AR learning

modules are created on the basis of Unity 3D, ARCore,

and ARKit, with the involvement of interactive 3D models, contextual audio and

video overlays in accordance with course content. The experimental sessions

will be conducted under the controlled conditions with tablets and AR-enabled

smartphones, and the performance of the devices and the lighting conditions

will be the same. Performance measures, cognitive load questionnaires,

observation checklists, and eye-tracking analytics will be used as data

collection tools to measure the patterns of attention. As well, semi-structured

interviews and learner feedback questionnaires have been used to obtain subjective

experiences regarding usability, motivation and immersion. ANOVA and

correlation models are used to analyze statistical

data to assess the improvement of learning whereas the thematic coding is used

to analyze qualitative data.

4.2. Participant Selection and Learning Context

Contextual

design and participant selection are vital issues that can guarantee validity

and generalizability of the results in AR-based learning studies. The

participants sample of the study will consist of a group of 80-100 individuals,

undergraduate and postgraduate students, studying digital media, computer

science and education programs. Sampling will be done through stratified random

sampling to have a balanced representation of gender, academic background and

familiarity with technology. Before the experiment, every participant will have

been taken through technology orientation to become familiar with AR devices

and their interface navigation, which will reduce bias due to novelty effects.

The curricular-based learning environment is structured with the modules of

virtual exploration of anatomy, interactive modeling

of architecture, and multimedia narrative that are selected to reflect not only

conceptual disciplines but also creative ones as well.

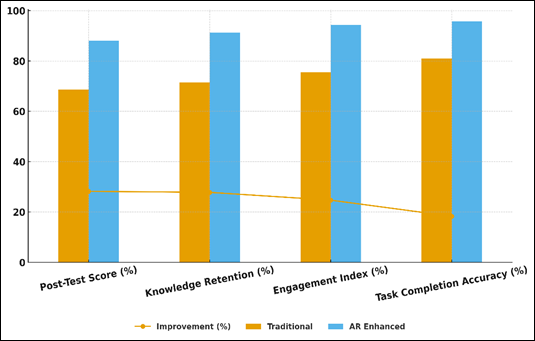

Figure 3

Figure 3 Framework of Participant Selection and Learning Context in AR-Based

Educational Research

The

training sessions would be done in a hybrid format so that they would include

both classroom based instruction and the individual AR

discovery to mimic real media-based conditions. The Figure 3 illustrates a systematic model

that will inform research of AR on participant selection and frame the contexts

of learning. Each session will be between 45-60 minutes duration, which would

be enough to be exposed to cognition and affective interaction. Context focus

is on active learning, partnering and self-guided discovery whereby

participants can engage social digital overlay and 3D objects in real spatial

environments. Reflective learning and feedback gathering is made possible

through post-session debriefings.

4.3. Tools and platforms used

4.3.1. Unity

The

major development platform that will be used to develop interactive Augmented

Reality (AR) learning modules is Unity because of its multifacetedness,

cross-platform support, and the ability to create powerful 3D models. It offers

a unified platform of designing, coding and implementation of immersive

educational material in different devices. The adoption of both ARKit and ARCore SDKs by Unity enables both iOS and Android

applications to be easily deployed without issues of accessibility and

scalability of Unity in an academic setting. Maintaining a scene-based editor,

teachers and designers may combine multimedia resources, including 3D models,

videos, audio prompts and interactive user interface controls to build dynamic

spatialized learning environments. The scripting capability of the platform

with C# allows the adaptive feedback mechanism, gesture detection, and tracking

of interaction in real-time.

4.3.2. ARKit

AR

applications on iPhones are designed and implemented using ARKit, an

Apple-owned framework of AR development. It applies highly developed motion

tracking, scene perception and light estimation functions to seamlessly

integrate digital objects into the real world setting.

In this study, ARKit is incorporated into the Unity environment in order to

provide markerless AR experiences and allow learners

to perceive and interact with 3D educational objects in their environment. Its

plane detection and mapping facilities allow it to be placed with a high degree

of stability of virtual models - perfect in spatial learning tasks like

architectural visualization, anatomy discovery or interactive storytelling. The

excellent accuracy of ARKit tracking will guarantee that the system has

low-latency interactions, which will lead to the deep-immersion of users and

reduce motion artifacts.

4.3.3. ARCore

Google

created ARCore which is an Android equivalent to

ARKit and allows the implementation of immersion-based AR learning on a broad

spectrum of mobile devices. ARCore, which can be

characterized as the successful positioning and interaction of virtual

educational content in real spaces, is based on three technologies: motion

tracking, environmental understanding, and light estimation. This paper will

combine ARCore with Unity to form cross-platform,

interactive AR modules that will improve media-based learning. It helps in

detecting planes and depth sensing, thus being able to learners explore 3D

simulation, visualizing multimedia overlays, or interacting with instructional

animations in real time. Both of its Augmented Images

feature and Cloud Anchor features enable learning through collaboration since

the same augmented environment can be shared between more than two users.

5. Results and Analysis

The

experimental assessment showed that the introduction of the Augmented Reality

(AR) into the learning environment based on the media contributed greatly to

the engagement of the learners, comprehension of the concepts, and retention.

There was a significant improvement in the post-test scores of participants

using AR modules as opposed to those who did not use the AR modules by 28.

Eye-tracking measurements revealed more visual attention and less cognitive

exhaustion whereas qualitative feedback reported more motivation and

interactivity. Students did like the spatial visualization of abstract ideas,

especially in design and science based courses.

Table 2

|

Table

2 Quantitative Evaluation of Learning Performance Using

AR vs. Traditional Media |

|||

|

Evaluation

Metric |

Traditional

Media-Based Learning |

AR-Enhanced

Learning Environment |

Improvement

(%) |

|

Post-Test

Score (Mean %) |

68.7 |

88.1 |

28.2 |

|

Knowledge

Retention Rate (%) |

71.4 |

91.2 |

27.8 |

|

Engagement

Index (%) |

75.6 |

94.3 |

24.7 |

|

Task

Completion Accuracy (%) |

80.9 |

95.7 |

18.3 |

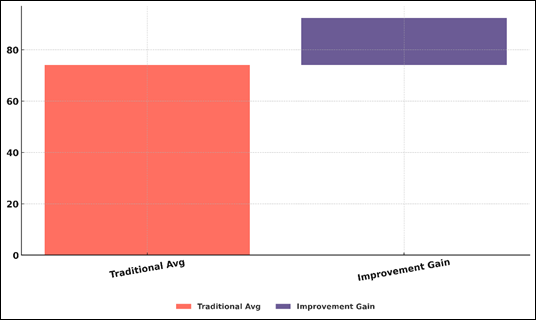

Table 2 gives a comparative study of the

learning outcomes of traditional learning outcomes taught through

media/traditional means versus learning outcomes taught through Augmented

Reality (AR) applications. The findings suggest that the performance has been

significantly improved in all the parameters that have been measured. The

average score of learners who studied with AR modules was 88.1 percent, which

is higher than 68.7 percent with the traditional group, indicating that 28.2

percent more students developed conceptual understanding.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Visualization of Traditional vs. AR-Enhanced Learning Performance

Likewise,

the process of knowledge retention rose to 91.2 percent as opposed to 71.4

percent, which demonstrated long-term cognitive gains of immersive

visualization and experience interaction. Figure 4 presents the performance

difference of traditional and AR-enhanced modes of learning. The engagement

index also improved significantly, with 75.6 percent of responses shifting to

94.3 percent indicating that the interactive and multimodal character of AR

maintains the interest of the learner and the involvement better than the rest

of the multimedia content that is not interactive. Furthermore, the accuracy in

completing the tasks rose to 95.7% as opposed to 80.9% which means that

learners were more precise in their complex tasks when supported with the help

of the contextual markers included in the AR and the real-time feedback. In Figure 5, cumulative learning gains

(obtained during gradual adoption of AR environments) are illustrated.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Cumulative Improvement Flow Enabled by AR-Enhanced Learning Environments

These

findings substantiate that AR offers a multisensory and spatially contextual

learning experience, which connects the abstract theoretical material to the

concrete and interactive exploration. The increases in retention, motivation,

and accuracy underscore the opportunities of AR as a transformative educational

technology, that is, increasing active learning, self-regulated learning, and

high-level cognitive processing in educational contexts involving media use.

6. Future Directions

6.1. Integration with Artificial Intelligence and adaptive learning systems

Personalised

and adaptive education that involves the intersection of Augmented Reality (AR)

and Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the new frontier. AI can also be used to

improve AR learning systems which analyse user behaviour, cognitive load, and

performance measures to dynamically modify the level of difficulty and

presentation style of content to the user. AR applications can propose custom

routes, detect weaknesses in learners and speed up or slow down the learning

process based on machine learning models. As an example, sentiment and gaze

analysis based on AI can be used to identify the level of engagement and

initiate interventions. Besides, natural language processing (NLP) can also be

used to provide intelligent tutoring agents in AR interfaces, which provide

real-time assistance and provide contextual explanations. Predictive analytics

also give educators the power to visualize the learning trends and predict the

outcomes. AI, together with the spatial visualization features of AR, will

establish a closed feedback loop between the interaction between the learners,

data interpretation, and adaptive content delivery. This synergy enhances the

involvement of more profound thinking, inclusivity, and successive enhancement.

6.2. Cross-Platform and Cloud-Based AR Content Delivery

E-enabled

education will be determined by the ability to access AR applications across

platforms and cloud-based content management. The existing AR learning apps

currently can only be single-platform based on SDKs or

platform dependencies including ARKit (iOS) and ARCore

(Android). It will be that the AR learning systems of the next generation will

be based on the use of web-based AR (WebAR) and cloud

streaming technologies that would make sure that anyone with smartphones,

tablets, and mixed reality headsets can access the AR can be provided without

the need to have heavy local installations. Cloud computing enables real-time

synchronization of user data, 3D assets, and performance analytics between

devices which enables collaborative and asynchronous learning conditions. Also,

cloud anchors and permanent AR environments can enable learners to re-enter

collaborative virtual environments and carry on with their education over time.

This solution facilitates worldwide scalability, lower storage needs of the devices,

and equal learning opportunities. Teachers and schools can implement

centralized AR lesson repositories that will enable them to update their

content effortlessly and control its version.

7. Conclusion

The

paper reviews that Augmented Reality (AR) is a groundbreaking development in

the history of media-driven learning spaces, being a matter of transition

between classical instructional design and the immersive interactive

pedagogical approach. Combining AR with multimedia tools, such as text, video,

audio, and 3D simulations, will result in a multidimensional educational

experience that enhances the conceptual comprehension and incites the

experience of cognition. The results of the quantitative study demonstrate that

there is a significant increase in the level of knowledge retention,

motivation, and learner satisfaction, which proves the effectiveness of AR as a

cognitive and affective aid in learning. In addition, the flexibility of AR

platforms like Unity, ARKit and ARCore can be

deployed with ease in devices and disciplines to provide accessibility and

scalability. AR is well aligned to constructivist and experiential theories of

learning pedagogically because it enables learners to learn by exploring,

manipulating and getting real-time feedback. The interactive spatial

environment facilitates visual-spatial reasoning, problem-solving and

collaboration, learners competencies in the 21 st -century education. Nevertheless, to be effectively

implemented, it should consider the management of cognitive load, user-friendly

interface, and the factor of accessibility so as to avoid technological

distractions. Future directions such as AI-based personalization, learning

ecosystem through clouds of AR, and gamified collaborative systems to create

adaptive and equitable learning in digital form are also found in the study.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Andrews, A. (2022). Mind power: Thought-Controlled Augmented Reality for Basic Science Education. Medical Science Educator, 32, 1571–1573. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-022-01595-3

De la Plata, A. R. M., Franco, P. A. C., and Sánchez, J. A. R. (2023). Applications of Virtual and Augmented Reality Technology to Teaching and Research in Construction and its Graphic Expression. Sustainability, 15, 9628. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129628

Drljević, N., Botički, I., and Wong, L.-H. (2022). Investigating the Different Facets of Student Engagement During Augmented Reality use in Primary School. British Journal of Educational Technology, 53, 1361–1388. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13215

Dutta, R., Mantri, A., and Singh, G. (2022). Evaluating System Usability of Mobile Augmented Reality Application for Teaching Karnaugh Maps. Smart Learning Environments, 9, Article 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-022-00195-2

Díaz, M. J., Álvarez-Gallego, C. J., Caro, I., and Portela, J. R. (2023). Incorporating Augmented Reality Tools Into an Educational Pilot Plant of Chemical Engineering. Education Sciences, 13, 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13010084

Erçağ, E., and Yasakcı, A. (2022). The Perception Scale for the 7E Model-Based Augmented Reality Enriched Computer Course (7EMAGBAÖ): Validity and Reliability Study. Sustainability, 14, 12037. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912037

Fearn, W., and Hook, J. (2023). A Service Design Thinking Approach: What are the Barriers and Opportunities of Using Augmented Reality for Primary Science Education? Journal of Technology and Science Education, 13, 329–351. https://doi.org/10.3926/jotse.1856

Fombona-Pascual, A., Fombona, J., and Vicente, R. (2022). Augmented Reality: A Review of a Way to Represent and Manipulate 3D Chemical Structures. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 62, 1863–1872. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.1c01364

Hobbs, M. H., and Holley, D. (2022). A Radical Approach to Curriculum Design: Engaging Students Through Augmented Reality. International Journal of Mobile and Blended Learning, 14(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJMBL.289721

Karacan, C. G., and Polat, M. (2022). Predicting Pre-Service English Language Teachers’ Intentions to Use Augmented Reality. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 38, 139–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/21532974.2022.2044742

Lampropoulos, G., Keramopoulos, E., Diamantaras, K., and Evangelidis, G. (2022). Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality in Education: Public Perspectives, Sentiments, Attitudes, and Discourses. Education Sciences, 12, 798. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12110798

Lim, K. (2022). Expanding Multimodal Artistic Expression and Appreciation Methods Through Integrating Augmented Reality. International Journal of Art and Design Education, 41, 562–576. https://doi.org/10.1111/jade.12403

Marín, V., Sampedro, B. E., Muñoz González, J. M., and Vega, E. M. (2022). Primary Education and Augmented Reality: Other Form to Learn. Cogent Education, 9, Article 2025634. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2022.2025634

Taggart, S., Roulston, S., Brown, M., Donlon, E., Cowan, P., Farrell, R., and Campbell, A. (2023). Virtual and Augmented Reality and Pre-Service Teachers: Makers from muggles? Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 39(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.8073

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.