ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Data Visualization as a Form of Sculptural Art

Manivannan Karunakaran 1![]()

![]() ,

Praney Madan 2

,

Praney Madan 2![]()

![]() ,

Sachin Pratap Singh 3

,

Sachin Pratap Singh 3![]()

![]() ,

Peeyush Kumar Gupta 4

,

Peeyush Kumar Gupta 4![]()

![]() ,

Mohd Faisal 5

,

Mohd Faisal 5![]()

![]() , Fazil Hasan 6

, Fazil Hasan 6![]() , Mahesh Kurulekar 7

, Mahesh Kurulekar 7![]()

1 Professor

and Head, Department of Information Science and Engineering, JAIN (Deemed-to-be

University), Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

2 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

3 Assistant

Professor, Department of Journalism and Mass Communication, Vivekananda

Global University, Jaipur, India

4 Assistant

Professor, ISDI - School of Design and Innovation, ATLAS SkillTech

University, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

5 Lloyd Law College, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201306, India

6 Associate

Professor, School of Business Management, Noida international University, India

7 Department

of Civil Engineering Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra,

411037, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Data

visualization, the interconnection of information and sculptural art is a new

paradigm where information moves out of the digital screens and finds space

in the physical world to express itself. This paper examines the conceptual,

aesthetic and technological systems that allow the data to be physically

realized as three dimensional artworks. It investigates how datasets are

transformed algorithmically and modeled computationally into forms that

provoke sensory, emotional and intellectual interaction. The paper

contextualizes the current practices in the context of the historical path of

abstract visualization and data physicalization to

identify the connection of the modern practice with the information design

and artistic tradition. The research methodologically describes the following

processes: the choice of the dataset, semantic-geometric mapping, application

of digital fabrication tools, including 3D printing, CNC, and laser cutting.

Machine learning adds value to the technological ecosystem by supporting

pattern extraction, generative modeling through Grasshopper and Houdini, and

previews of the sculpture in real-time. The aesthetic inquiry is concerned

with the ability of the physicalized information to tell visual tales,

mediate perception, balance between science and creative interpretation. It

is further discussed with regards to issues of material constraints,

sustainability and representation of multidimensional datasets. This study,

finally, makes the data-driven sculpture be both an art and an

epistemological practice, i.e. the way of turning data into an embodied and

spatial conversation of information, materiality and human experience. |

|||

|

Received 18 April 2025 Accepted 24 August 2025 Published 25 December 2025 Corresponding Author Manivannan

Karunakaran, manivannan.k@jainuniversity.ac.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i4s.2025.6863 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Data Physicalization, Generative Design, Computational

Sculpture, Aesthetic Information Mapping, Digital Fabrication |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Data visualization has taken the form

of the interface between creative expression and analytical thinking in the

changing world of art, design and information science. Visualization has

traditionally been focused on the two-dimensional charts, infographics and

dashboards and helped to make sense of complex data by converting numerical or

categorical data into visual patterns that can be observed. Nevertheless, with

the emergence of new computational technologies, generative modeling,

and the physicalization of data, this area has now

gone beyond the flat screen- it is now physically represented as data physicalization or sculptural visualization. This change

does not just imply a shift in medium but paradigmatic shift in the way in

which data may be perceived, understood and embodied. The process of

transforming abstract data into three-dimensional sculptural constructions

changes the interaction between the object, information, and the viewer,

establishing novel perception, emotion, and interaction possibilities. The

concept of data as matter is consistent with the wider art trends that mislead

the boarders between science and aesthetics Nisiotis et al. (2020). According to the same logic as the traditional sculpture,

where imagination and physicality are transformed into form, the data-driven

sculpture combines algorithmic logic with artistic intent, bringing thoughtless

phenomena into the real world, as the material interactive sculpture. An

example would be the metrics of climate change in the form of undulating

topographies; the feelings of the social media in the form of pulsating organic

forms; and the sound frequencies represented by a complex lattice. These

representations disrupt the traditional definition of art and analytics since

it no longer revolves around accuracy but rather expressive embodiment, the

place where the meaning is created through the combination of information,

design and physical environment Monaco et al. (2022).

Gradually, with the democratization of

computation, as made available through software such as Processing,

Rhino-Grasshopper and TouchDesigner, artists and

designers developed a new mode of engagement through information, as both input

and co-creator in the generative process. This development is a major point of

convergence of art and technology - making datasets sculptural grammars that

can be created, displayed, and touched in the physical world. Regarding the

perception, sculptural data visualization allows the experience of a

multi-sensory perception. Physical forms, unlike the visualizations on the

screen, touch, spatial orientation and emotional resonance are all used Bekele et al. (2018). This was a dimension of touch that helps to create a

deeper sense of connection with the audience and makes the audience curious and

reflective. It makes information interpretation more democratic, as any human

being, not only specialists, is able to explore information physically,

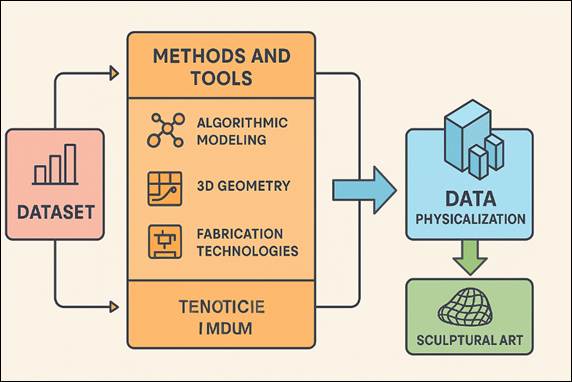

understand patterns and feel the connection. Figure 1 demonstrates

multistage framework on the basis of which data is

converted into expressive visualizations in sculptural form. Additionally,

these physical experiences have the ability to cross over linguistic and

cognitive boundaries so that complex data could speak conceptually using space

and material representation.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Multistage Framework of Data

Visualization as Sculptural Art

This new form of art provides a merging

of data analytics, machine learning, and generative design that is

technologically exploited. Parametric and algorithmic design tools transform

the patterns found in datasets into morphologies that can be fabricated,

whereas machine learning models reveal the latent patterns found in the

datasets. In terms of digital models, 3D printing, CNC milling and laser

cutting, techniques bring digital models into contact with material reality,

and translation of pixels into physicality, in other words, is smooth Maiwald et al. (2021). Such sculptural works are frequently supplemented with

interactive and kinetic, in which the sculpture is sensitive to real-time data

feeds, and thus represents a story in flux.

2. Theoretical Foundations

2.1. Definitions of data visualization, physicalization, and sculptural interpretation

Data visualization is the art of

interpreting either numerical or categorical data in visual ways that can be

used to identify patterns, generate insights as well as communicate. It is a

cognitive interface between the complexity of information and human perception

in that abstract datasets can be perceived in the form of color,

geometry and space. However, data physicalization

takes this process one step further into the physical world, where data is

instantiated in the form of physical, and often three dimensional, objects Rahaman et al. (2019). These objects may be passive or interactive and the users

are invited to engage with information by touching it, moving it, and

navigating a space. Physicalization makes

visualization physical, so that information which is abstract and intangible is

actualized in three-dimensional sculpture that blends informational logic with

aesthetic purpose Arrighi et al. (2021).

2.2. Historical Evolution from Symbolic Abstraction to Tangible Forms

The evolution of the symbolical

abstraction into the physical data representation is both the indicator of the

technological progress and the alterations of the thought of the art. The

origins of visualization that include the statistical charts developed by

William Playfair in the 18th century may be regarded as the foundation of the

symbolic form of abstraction since both of them attempted to reach the clarity

through the use of geometric simplicity. As the speed of computing increased in

the 20th century, information visualization started to take center

stage in the scientific exploration in the shape of digital graphs, network

maps, and algorithmic renderings that reduced the complexity to abstract visual

syntax Ceccotti (2022). With this also came a new generation of cybernetic and

information aesthetics, including Max Bense and Herbert Franke, which began to

conceptualize in terms of information as an art material, and to emphasize the

aesthetic constituent of information. Experimental intersections were pursued

in the 1960s and 1970s by artists such as Vera Molnar and Frieder Nake and

Edward Ihnatowicz to make geometric compositions and robotic sculptures. These researches marked the transition to the data-driven art

concept to combine the rational programming with the sensory representation Rauschnabel et al. (2022). Later 20th and early 21st centuries gave such

conceptualizations digital construction, and parametric modeling

and made the data physically manifest itself in sculptural forms possible.

2.3. Conceptual Frameworks Linking Aesthetics, Perception, and Information Design

Theoretical models of the relationships

between aesthetics, perception, and information design explain human cognition

in information-processing modes other than the analytical-cognitive one sensory

and emotional cognition. The Gestalt-based perception theory postulates that

people desire to achieve coherence and pattern recognition in visual forms.

When this principle is applied to the data visualization and physicalization, aesthetic harmony, balance, and rhythm

help to understand. Aesthetics, in turn, does not serve as ornamentation but as

an epistemological instrument which contributes to more understanding and

emotional appeal Theodoropoulos and Antoniou

(2022). In information design, aesthetics is the facet between

disclosure and involvement. Perceptual affordances are directed toward

attention and meaning-making by the material, color

and spatial organization. Intentionality Artistic intentionality adds to this

model: visualizations in sculpture goes beyond a description of data to include

interpretive stories that arouse the imagination and thought. Table 1

summarizes related works in terms of the methods, use of data, contribution and

limitation. Fusing semiotics, the study of signs and meaning, with

computational design, such works convey in both quantitative and qualitative

truth, the quantitative truth of information and the qualitative truth of

composition.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Comparative Overview of Related Works in

Data-Driven Sculptural Visualization |

||||

|

Project Title |

Data Type Used |

Technique |

Material or Medium |

Impact |

|

Artistic Data Sculptures for Social Visualization |

Social Media Text Data |

Aggregated Pattern Mapping |

Acrylic Layers |

Enhanced audience empathy via transparency and

layering |

|

Opportunities and Challenges for Data Physicalization |

Multivariate Data |

Data-to-Form Encoding Framework |

Mixed Materials |

Defined taxonomy for physicalization

approaches |

|

Exploring Tangible Data Representations |

Quantitative and Qualitative Data |

Tangible Interaction Models |

3D Printed Objects |

Highlighted tactile engagement benefits |

|

Data by Proxy: Material Traces and Quantified

Reality Lo Turco et

al. (2022) |

Urban Environmental Data |

Trace-Based Physical Mapping |

Metal & Concrete |

Connected environmental sensing with artistic

form |

|

Data Physicalization:

From Visual to Tangible Willkens et al. (2020) |

Scientific Data |

Algorithmic Mapping to Geometry |

PLA / Resin |

Promoted hybrid data interpretation frameworks |

|

Affective Data Sculptures: Emotive Quantification |

Biometric / Emotional Data |

Generative Emotion Mapping |

3D Printed Resin |

Demonstrated emotional connection via physical

data |

|

Critical Info-Aesthetics Pourmoradian et al. (2021) |

Cultural & Textual Data |

Conceptual Visualization |

Paper / Wood |

Encouraged critical interpretation over utility |

|

Tangible Topographies of Data |

Geospatial / Climate Data |

Topographic Height Mapping |

CNC Wood Panels |

Enhanced geographic cognition through tactile

surfaces |

|

Algorithmic Art and Information Aesthetics El-Said and

Aziz (2022) |

Mathematical Structures |

Algorithmic Plotting |

Ink / Plotter |

Inspired digital-to-physical generative art

lineage |

|

Embodied Data Narratives in Installation Art |

Behavioral Data |

Generative Spatial Composition |

Metal Frames + Light |

Fostered immersive environmental storytelling |

3. Data Physicalization and Sculptural Expression

3.1. Principles of transforming datasets into three-dimensional structures

Convergence of data science,

computational geometry and aesthetic design is the key to transformation of

datasets into three dimensional structures. The basic principle is to map the

abstract variables on spatial dimensions whereby the numerical or categorical

data defines the data parameters like the shape, scale, curvature, texture, or

density. That process turns the raw data into an embodied spatial narrative

that allows perceiving patterns in terms of volume and proportion Luther et al. (2023). The overall shapes are not literal copies of information

but beautiful representations which strike a balance between accuracy and

expressionism. Also, the symmetry aspect, rhythm and structural stasis play a

role in the final result, making sure that the sculpture has artistic unity, as

well as, material viability.

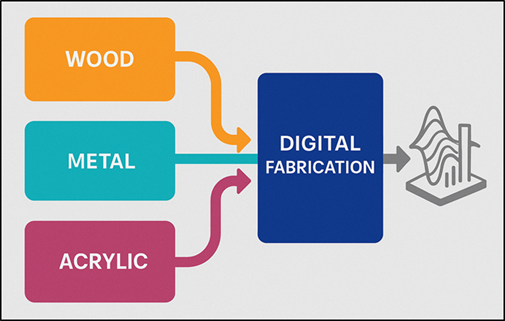

3.2. Materiality and Form: Wood, Metal, Acrylic, Digital Fabrication

Materiality is very important in

defining how the data-driven sculptures convey meaning, emotion, and the sense

of touch. The decision of material, whether it is a wood, metal, acrylic or

hybrid composites is not only an aesthetic but a conceptual decision, between

the physical and informational dimension of the piece of art Pisoni et al. (2021).

Wood is cozy, organic, and man-made,

and is typically appropriate in the depiction of ecological or chronological

data. Figure 2 indicates the combination of materiality and form to make

data-driven sculptural objects. Its texture and grain bring in a natural

irregularity to counter anything that is algorithmic and focus on the

discussion between nature and data. Metal, as a material that is rigid and

reflective, is an icon of strength, modernity and permanence. Industrial or

infrastructural data can be represented as stainless steel or aluminum, whereas more complex inscriptions of data can be

made on surfaces, such as anodizing or laser etching. The transparency of

acrylic and other translucent materials is used as a metaphor of clarity, flow

and immateriality, which is best suited to represent light-based or fluid

datasets. These materials are dynamically receptive to lights and cast changing

patterns and shadows, which bring the data experience out into environmental

space.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Materiality and Form Integration in Data-Sculptural

Fabrication

3.3. Spatial Composition, Embodiment, and Viewer Interaction

In data-based sculpture, spatial

composition characterizes the positioning and relations of information

concerning physical and perceptual space. In contrast to the conventional

visualization where meaning is limited to a frame or a screen, data sculpture

as a spatial experience is a three-dimensional experience. The composition is a

coordination of scale, direction, rhythm, to define the way the viewer

perceives and manages the form. Designers apply rules of equilibrium,

repetition and contrast to scale data relationships into choreography of

volume- where every curve, gap or density contains a certain pattern of

information. Embodiment introduces an additional performative aspect, which

places the data as well as the viewer into a common space of dialogue. With the

viewer walking about the sculpture, there is a change in perspective as new

correlations and hierarchies become evident and thus observation becomes

interpretation. The interactive technologies like sensors, LEDs, or kinetic

mechanisms are incorporated in some works and react to real-time streams of

data or the nearness of the audience.

4. Methods and Design Process

4.1. Dataset selection and semantic mapping to 3D geometry

The making of data-driven sculptures

starts with the strategic selection of the dataset, thus defining the

conceptual purpose as well as the logic of the structure behind the final form.

The selected data set should be semantically rich - it needs to have a story or

a thematic meaning which qualifies its translation into a physical form. As an

example, the climate records, or population movements or emotional sentiment

data each have visual languages that are distinctly dissimilar when turned into

geometry. One should not reproduce the data word-to-word but rather distill the expressive properties of the data to find the

variables that can be expressed by the means of shape, volume, and material.

After curating and cleaning the data, the next stage is called semantic mapping

and it involves matching data variables with the associated geometric

parameters. Spatial elements like height, curvature or density are associated

with quantitative aspects like frequency, magnitude or correlation. Colors, textures or modular arrangements can be defined by categoricals. Such mapping creates a visual grammar, which

allows data relationships to appear in the three-dimensional structure.

4.2. Algorithmic Modeling and Computational Design Techniques

Data-sculptural design consists of

algorithmic modeling as its creative and technical

backbone, that is, semantic mappings are transformed into actual geometries by

rule-based computation. Algorithms in this stage are generative systems that

perceive the information input to create complex forms that cannot be created

manually. Parametric and procedural modeling

Designers utilize parametric and procedural modeling

tools such as Rhino -Grasshopper, Houdini, and Processing to define the

relationships between the data parameters and geometric changes. The

constraints, iterations, and dependencies are encoded by each algorithm

resulting in a structure that is living and changes depending on variations in

the dataset. There are technologies like lofting, mesh subdivision, Voronoi

tessellation and point-cloud reconstruction to form organic and not a priori

complex surfaces and spatial patterns out of data-driven logic. Machine

learning models can additionally be applied in generative design processes to

discover latent models or to optimize aesthetic settings. The precision and

serendipity created by these computational systems allow designers to improvise

a space of design by searching vast and algorithmically created designs.

4.3. Integration of fabrication technologies

4.3.1. 3D printing

With the use of 3D printing, it is

possible to transform digital models to tangible data sculptures with its high

accuracy and geometric complexity. Additive manufacturing is used to fabricate

forms of an algorithmic nature by layering material, usually resin, PLA or

metal powder, sequentially to build up the desired shape. The method is most

suited to the manufacture of convoluted lattices or organic encodings of

geometries and volumetric data that would not have been possible in a manual

fabrication procedure. 3D printing can also be used to print multi-material and

color data such that categorical or scalar

information can be represented directly in the texture or colour of the

structure. Its easy approach, and also scalability are handy in the exploration of prototypes, as well as in

end sculptural installations. Of significance, 3D printing offers a links data

abstraction and physical representation to offer material mode of computation

in which computational aesthetics are brought to life. The printed edition is a

digital piece of digital intelligence - all the layers are parts of material

documentation of an algorithmic process, that is, it unites information

science, accuracy of the engineering and art intent into a material

representation.

4.3.2. CNC

CNC machines cut substances- be it

wood, metal or foam using information created geometries in order to disclose

spatial structures which possess informational significance. The CNC material

reduction process compared to an additive technique is concentrated on

articulation of surfaces, depth and tactile grain - interaction of mechanical

precision and natural flaw. Parametric toolpaths of designers are designed

using data driven algorithms, in which every cut is dependent on a variable in

a dataset or a spatial relationship. CNC machining is especially most suitable

in large or permanent installations, where physical robustness and textual

articulateness is needed. It allows intricate contouring, multi-axis carving as

well as hybrid assembly with other fabrication techniques. CNC will, therefore,

be a translator and sculptor, bringing computational form to the physical

through very fine control of motion, transposing digital patterns into physical

forms which combine the rigorousness of engineering practice with the

expressiveness of sculptural art.

4.3.3. Laser Cutting

Laser cutting offers a quick and

precise procedure of making planar or modular parts of data sculptures. With a

focused beam of laser, acrylic, wood, or metal sheets are cut, etched or

engraved accurately following algorithmic patterns based on datasets. The

method is skilled at creating stratified, interlocking or grid-based

visualizations regarding two-dimensional information associations where

physical assemblage is recast as a

information association. Laser cutting is commonly used in design by designers

in data stratification, in which every layer corresponds to a time, category,

or statistical dimension. These layers create volumetric illusions- when

stacked or suspended, the data of light, shadow, and translucency are converted

into a spatial composition, a flat data.

5. Technological Ecosystem

5.1. Role of data analytics, machine learning, and pattern extraction

Scientific data transformation Raw data

is converted into structured understanding informative of aesthetic form by

using data analytics and machine learning, which are the main focus of

sculptural data visualization. Precision, relevance and context are guaranteed

with the help of data analytics, and unprocessed numbers can be transformed to

the form of understandable variables that can be coded spatially. Patterns are

formed as a result of descriptive, predictive and exploratory analysis that

forms the conceptual blue print of physical manifestation. Some of the hidden

structures of big or complex data sets are revealed or uncovered using machine

learning like clustering, regression and dimensionality reduction algorithms.

Examples are the principal component analysis (PCA) or t-SNE to cluster

high-dimensional data in useful visual axes which can be then overlaid on

geometric features, like curvature, volume or symmetry. The idea of neural

networks and generative models are also included in the list of creative

variability, and the data may evolve to these expressive forms, that is,

combining the accuracy and unpredictability.

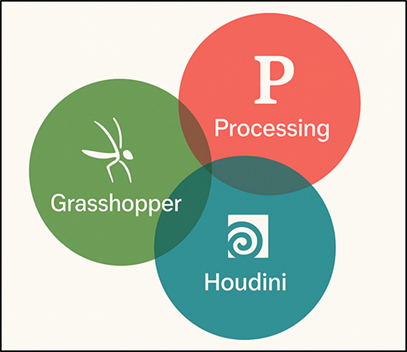

5.2. Parametric and Generative Design Tools

The creative center

of data-sculptural processes is made of parametric and generative design tools

which allow designers to convert datasets into dynamic and adaptable

geometries. Programs like Grasshopper to Rhino, Processing, and Houdini offer

an algorithmic environment where form is created through given relationships,

and not fixed size. In parametric modeling, each

structural element, whether curve, point, or surface will have adjustable

parameters that are associated with data values. This enables the real time

manipulation and the iterative refinement of the design, to make sure that the

evolution of design is as variably represented as the dataset it is based on.

Grasshopper is exceptional in the field of spatial logic and architectural

structuring and allows designers to create direct data-geometry pipelines.

Processing is a visual programming language that is used to create interactive

and generative graphics, which is best suited to exploratory modeling or visual pattern prototyping. Figure 3 demonstrates that adaptive data-sculptural models are

influenced by parametric and generative design tools. The procedural node based system of Houdini is able to

support complex simulations, particle systems and volumetric modeling where data can be used to create organic and fluid

morphology.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Parametric and Generative Design

Tools in Data-Sculptural Modeling

Collectively, these technologies bring

about generative authorship in which designers are in between algorithmic

intelligence and aesthetic judgment. The process of work turns into a cyclical

process - data is the source of form, form is the source of reinterpretation,

and computation changes itself in response to the former. Coupling logic and

spontaneity, the parametric and generative tools are able to make the design

process an alive system of emergence, able to create sculptures that are

mathematically consistent as well as artistically suggestive, that is to say,

in the rhythm of the data in a form of spatial motion.

6. Aesthetic and Interpretive Dimensions

6.1. Visual storytelling through physical form

In data sculpture, visual narrative is

performed by bringing abstract information to form, texture and space. As

compared to traditional narratives, which depend on text or image, sculptural

storytelling relies on the spatial rhythm, proportion, and touch to convey some

meaning. Every curve, every hollow, or every line turns into a piece of story,

a coded bit of information, which, when combined together, turns into a story

of change, association, or creation. The grouping of elements, gradients and

densities reflect the relationships of time or rank among sets of data, and

convert numerical acts into gestures of symbols. This type of narration

survives on metaphor. The statue of the variation in climate could be waving

like a tide, and the statue of the social networks could be a tree that could

be fractured into some branches. These kinds of symbolism enable information to

be not only understood but also evoked, so that the viewer can experience

patterns, but not read them. The material decisions, to use clear acrylics or

oxidized metals add to the reverberation of the narration, and indicate the

data themes such as transparency, corrosion, or flux. Composition, light and

perspective of the sculpture make it an experiential field of narrative

involving audiences in the interpretive participation. As the viewers navigate

through it, new alignments and visual relationships are created and the

information that was stagnant is dynamic as stories are told. Accordingly, the

sculptural system becomes a multimodal narrative tool as data analysis is

turned into poetic embodiment, and information begins to speak the universal

language of space and sensual perception.

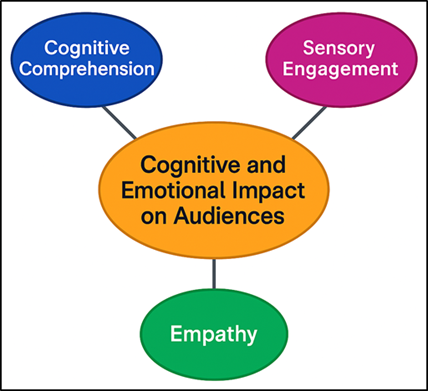

6.2. Cognitive and Emotional Impact on Audiences

The emotional and mental effect of the

data sculptures is determined by the possibility to merge logical understanding

and experience. Contrary to the visualizations found on screens, which favor analytical vividness, physical data representations

entail incorporating more than just one of the perceptual senses: sight, touch,

movement, scale, etc., forming a bodily experience with information. This

multi-sensory interaction enables embodied cognition so that data are processed

in a spatial and intuitively, not abstractly, way by the viewers. As seen in Figure 4, there is a framework of connection of cognitive and

emotional influences in data-sculptural artworks. The brain perceives

proportion, rhythm, and balance as some kind of innate stimulus and transforms

statistical relations into experiences.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Cognitive and Emotional Impact

Framework in Data-Sculptural Art

Sculptural visualizations have the

emotional power to convert unemotional information into emotional existence. A

curvy and wavy surface can be an expression of growth or peacefulness; the

rough, disorganized shapes can be an expression of war or violence. This

emotional appeal is based on aesthetic empathy, the ability of human beings to

project sensation into perceived forms. The sculpture causes a feeling of

connectivity and relation by placing the viewer into the physical space of the

data, making global datasets, such as the deforestation or migration,

accessible as personal experiences of scale and impact.

6.3. Balancing Abstraction, Accuracy, and Expressive Intent

The paradox of data-sculptural practice

is to effect a ratio between the abstraction, the

accuracy and expressiveness. Total fidelity of information ensures

informational integrity but may produce graphically rigid or impossible

information, and excessive abstraction may result in an absence of meaning. Balance

is an art form that involves the construction of the forms that would be true

to the nature of the dataset and promote the interpretive interaction.

Cognitive intelligibility and aesthetic richness are not sacrificed in the

selective simplification, scaling and metaphorical translation process of

designers. This process of simply viewing complexity in order to perceive

patterns that can be understood in order to make the mind to know about the

general relationships is the abstraction of visual language. Nevertheless,

these abstractions are grounded in accuracy which makes them remain

proportionate, have relational integrity and structural hierarchy to enhance

credibility. The expressive aspect, in its turn, adds human touch to the

sculpture, which is achieved as a result of material symbolism, movement, and

rhythm. This tripartite accord necessitates the refinement process and

precision of calculations is joined with the instinct of art. Algorithms can

achieve quantitative consistency, whereas interpretive hierarchy is maintained

by the designer, and he or she decides the fineness of the data that will take

the lead in the visual narrative.

7. Conclusion

Sculptural art form of data

visualization redefines human perceptions, interpretation as well as

experiences with respect to information. It permeates conventional divisions of

charts, graphs, computer displays in that it brings data to life in the form of

corporeal and spatial narratives that incorporate analytical precision and

beauty. The synthesis of computational modeling,

machine learning, and digital fabrication produces abstract datasets in a

touchable, explorable, and emotionally engaging form to represent them as

sculptural embodiments. A combination of science, technology and art such like

this enables the information to speak more than mind to stimulate feeling,

compassion and thought. It is pointed out in the paper that physicalization

of data is not a visualization process, however, it is a process of translation

and transformation. It decodes numeric logic at a sensual level, between the

spiritual realm of digital information and material realm of material space.

All sculptural manifestations of expression become a dialogue between accuracy

and fantasy and cause the viewers to think about the hidden rhythms of how the

mechanisms structure our reality, society, and emotions. However, it is not an

easy process and fidelity, issues of scale, sustainability and interpretive

ambiguity are still present. However, such limitations also contribute to

resourceful problem solving, which creates cross-disciplinary collaboration of

artists, designers, engineers, and data scientists. The chance of dynamic, interactive

and adaptable sculptures is even increasing with the development of fabrication

technologies.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Arrighi, G., See, Z. S., and Jones, D. (2021). Victoria Theatre Virtual Reality: A Digital Heritage Case Study and User Experience Design. Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage, 21, e00176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.daach.2021.e00176

Bekele, M. K., Pierdicca, R., Frontoni, E., Malinverni, E. S., and Gain, J. (2018). A Survey of Augmented, Virtual, and Mixed Reality for Cultural Heritage. Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage (JOCCH), 11, 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1145/3167132

Ceccotti, H. (2022). Cultural Heritage in Fully Immersive Virtual Reality. Virtual Worlds, 1, 82–102.

El-Said, O., and Aziz, H. (2022). Virtual Tours as a Means to an End: An Analysis of Virtual Tours’ Role in Tourism Recovery Post COVID-19. Journal of Travel Research, 61, 528–548. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875211024893

Lo

Turco, M., Giovannini, E. C., and Tomalini, A. (2022). Parametric and

Visual Programming BIM Applied to Museums, Linking Container and Content. ISPRS

International Journal of Geo-Information, 11, 411.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi11070411

Luther, W., Baloian, N., Biella, D., and Sacher, D. (2023). Digital Twins and Enabling Technologies in Museums and Cultural Heritage: An Overview. Sensors, 23, 1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23031583

Maiwald, F., Lehmann, C., and Lazariv, T. (2021). Fully Automated Pose Estimation of Historical Images in the Context of 4D Geographic Information Systems Utilizing Machine Learning Methods. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 10, 748. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10120748

Monaco, D., Pellegrino, M. A., Scarano, V., and Vicidomini, L. (2022). Linked Open Data in Authoring Virtual Exhibitions. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 53, 127–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2021.11.002

Nisiotis, L., Alboul, L., and Beer, M. (2020). A Prototype That Fuses Virtual Reality, Robots, and Social Networks to Create a New Cyber–Physical–Social Eco-Society System for Cultural Heritage. Sustainability, 12, 645. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020645

Pisoni, G., Díaz-Rodríguez, N., Gijlers, H., and Tonolli, L. (2021). Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence for Designing Accessible Cultural Heritage. Applied Sciences, 11, 870. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11030870

Pourmoradian, S., Farrokhi, O. S., and Hosseini, S. Y. (2021). Museum Visitors’ Interest on Virtual Tours in COVID-19 Situation. Journal of Environmental Management and Tourism, 12, 877–885.

Rahaman, H., Champion, E., and Bekele, M. (2019). From Photo to 3D to Mixed Reality: A Complete Workflow for Cultural Heritage Visualisation and Experience. Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage, 13, e00102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.daach.2019.e00102

Rauschnabel, P. A., Felix, R., Hinsch, C., Shahab, H., and Alt, F. (2022). What Is XR? Towards a Framework for Augmented and Virtual Reality. Computers in Human Behavior, 133, 107289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107289

Theodoropoulos, A., and Antoniou, A. (2022). VR Games in Cultural Heritage: A Systematic Review of the Emerging Fields of Virtual Reality and Culture Games. Applied Sciences, 12, 8476. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12228476

Willkens, D. S., Haley, H. M., and Liu, J. (2020). Race, Space, and Digital Interpretation at Selma’s Old Depot Museum. Arris, 31, 108–118.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.