ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Cognitive Load Reduction in Media Learning via AI

Sangeet Saroha 1![]() , Dr. Praveen Priyaranjan Nayak 2

, Dr. Praveen Priyaranjan Nayak 2![]()

![]() , Darshana Prajapati 3

, Darshana Prajapati 3![]()

![]() , Raman Verma 4

, Raman Verma 4![]()

![]() , Manivannan Karunakaran 5

, Manivannan Karunakaran 5![]()

![]() ,

Kashish Gupta 6

,

Kashish Gupta 6![]() , Vijay Itnal 7

, Vijay Itnal 7![]()

1 Greater

Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201306, India

2 Associate

Professor, Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering, Siksha 'O' Anusandhan (Deemed to be University), Bhubaneswar, Odisha,

India

3 Assistant Professor, Department of

Interior Design, Parul Institute of Design, Parul University, Vadodara,

Gujarat, India

4 Centre of Research Impact and

Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab, India

5 Professor and Head, Department of

Information Science and Engineering, JAIN (Deemed-to-be University), Bengaluru,

Karnataka, India

6 Assistant Professor, School of

Sciences, Noida International University 203201, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh,

India

7 Department of Mechanical Engineering,

Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037 India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The momentum

of multimedia learning environments has increased the issues related to how

to administer the cognitive load of learners. The paper describes a

cognitively intelligent real-time detection of cognitive load and

next-generation media optimization framework that is based on Cognitive Load

Theory (CLT). The proposed system combines multimodal sensing (EEG,

eye-tracking, affective cues) with a hybrid CNN-BLSTM inference engine and an

RL-based adaptive controller to dynamically balance the intrinsic, extraneous

and germane cognitive load. The model was experimentally validated using 120

participants who showed that the model had a detection accuracy of 91.3% and

a positive correlation with self-reported mental effort (r = 0.84, p <

0.001). Students in the adaptive group were found to record a learning gain

that was 62 higher and a cognitive efficiency that

was 27 higher than that of the control group. The

physiological patterns were associated with stable attention (VAS ↑11%)

and moderate workload (CWI held constant within 0.55 0.65), which proved the

maintenance of cognitive balance. The results support the idea that

AI-mediated adaptation may be used to control mental effort, improve the

results of learning, and implement the concepts of CLT in practice. The study

lays a scalable and interpretable platform of human-centered, neuro-adaptive systems of learning that incorporate the cognitive theory

and machine intelligence to learn designing of the next-generation

educational systems. |

|||

|

Received 06 May 2025 Accepted 10 September 2025 Published 25 December 2025 Corresponding Author Sangeet

Saroha, sangeet.saroha@lloydlawcollege.edu.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i4s.2025.6854 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Cognitive Load Theory, AI in Education, Adaptive

Learning, Multimodal Sensing, CNN–LSTM, Reinforcement Learning, Cognitive

Efficiency, EEG, Eye-Tracking, Human–AI Collaboration |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The multimedia learning environment has transformed the way learners receive, process and store information given the ever increasing nature of such environments. Between the interactive videotapes and virtual labs to the level of the immersive experience in the augmented reality, the number of sensory inputs may surpass the cognitive processing capacity of the learner. The approach to this challenge lies in the postulates of Cognitive Load Theory (CLT), which focuses on the constraints of the working memory during the learning process. The cognitive load, in a sense, is the factor defining the ability of the learners to create and automatize the schemas when working with complex visual or verbal materials. Yet, with the advent of more dynamic and data-driven media learning, some of the traditional methods of teaching it tend to become ineffective when it comes to accommodating individual variations in cognitive load tolerance Lazer et al. (2018). This leads to a lack of understanding, discontinuous attention and poor learning. Artificial Intelligence (AI) becomes a revolutionary facilitator in the solution of these constraints. By providing the sense, interpretation, and adaptation of learning environments, AI presents an intelligent mediation layer and personalizes the instruction in accordance with the cognitive state of a particular learner. The algorithms of machine learning, including the convolutional neural networks (CNNs), recurrence networks (LSTMs) and the reinforcement learning models allow systems to process multimodal stimulus information, such as gaze patterns, pupil dilation, EEG signals, facial expression cues, and task performance indicators Tsai et al. (2018), Firth et al. (2019). With these inputs, AI systems can make inferences about real-time levels of cognitive load, and, in turn, manipulate the level of instructional complexity, instructional pacing, and media density. Basically, AI serves as a learning controller, which keeps maximizing the interaction between the learner and the content. In addition to detection, AI enables adaptive content orchestration, or simplifying, sequencing, or prioritizing components of multimedia, according to most likely predicted mental effort. As an example, the extraneous load created by redundant or cluttered visuals in the learners can be reorganized by AI-based interfaces, downsizing streams of information concurrently, or diverting modalities between text-based and narration-based presentation. In the same manner, the reinforcement learning agents are able to track the performance of the learner across a series of sessions and optimize the instructional strategies so as to balance the difficulty and understanding Jones et al. (2019). Not only is there a better retention and transfer of knowledge but a less complicated cognitive experience that fits into the mental beat of the learner.

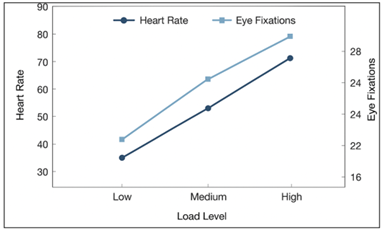

Figure 1

Figure 1 AI-Mediated Cognitive Load Reduction

Framework

This study is relevant to both the fields of educational psychology, artificial intelligence, and instructional design. The combination of the cognitive load theory and the adaptive learning models helps the study to see the future in which AI does not merely provide the personalized learning experience but also comprehends the cognitive state of the learner. The implications of such smart systems are enormous- e-learning platforms and virtual classes, corporate training and neuro-education applications Hung et al. (2020). The proposed study therefore focuses on designing and testing an AI-based framework to reduce cognitive load in the media learning environment, which has three folds (i) real-time cognitive state estimation, (ii) adaptive media optimization, and (iii) continuous learning efficiency reinforcement. Finally, the intersection of cognitive science and AI makes learning a symbiotic relationship between machine intelligence and human cognition in which it is defined. It is changing the media learning model, which is typically a fixed content delivery model into a responsive ecosystem, which is sensitive, adapts and evolves to each individual learner. This exploration forms the basis of measurable cognitive optimization and, with this advancement, genuinely intelligent and inclusive learning systems will be achieved by the paper.

1.1. Problem Definition and Research Gap

Although there has been multimedia learning advancement and artificial intelligence, the efficacy of alleviating cognitive load with adaptive systems has not been determined. The Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) is one of the ways of understanding how the human working memory works; however, the adaptations realized through AI-based learning platforms can scarcely be matched with its principles Hwang et al. (2020). The main problem is that there is no connection between the cognitive theory and computational practice- AI models recognize attention or engagement patterns but rarely explain them in terms of intrinsic, extraneous, and germane load. The existing systems are characterized by the fact that the modality combination is poorly gelled so that visual, textual, or behavioral information is analyzed separately. As an illustration, eye-tracking uses attention but not mental energy, whereas text analytics does not consider multimodal signals. This constrains cognitive profiling and gives incomplete adaptation. Similarly, there is a deficiency of adaptive calibration, AI models that are trained on small datasets do not generalize across age, expertise or cultural backgrounds. As a result, individual cognitive readiness is usually overlooked in personalized learning.

In summary, the key research gaps are:

1) Fragmented multimodal analysis.

2) Lack of adaptive and contextual calibration.

3) Reactive, not predictive, adaptation.

4) Poor theoretical alignment between CLT and AI.

2. Related Work

The history of research on cognitive load reduction in multimedia learning settings has experienced multiple conceptual and technological phases, starting with the initial psychological research, moving on to multimedia instruction design, and, lastly, the stage of introducing artificial intelligence (AI) to the process of cognitive regulation. This development is an ongoing effort to conceptualize and realize Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) empirically and with the aid of computational intelligence Khosravi et al. (2020). The following table (Table 1 below) summarizes the major contributions to the field of this trajectory and outlines methodological innovations, data modalities, and essential limitations driving the current study framework by AI.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary of Key Studies on Cognitive Load Assessment and AI-Based Adaptive Learning |

||||

|

Study

/ System |

Approach

/ Technique |

Data

Modalities Used |

Key

Findings |

Limitations

/ Gaps |

|

Early

Cognitive Load Models Martin et al. (2020) |

Subjective

rating scales (Cognitive Load Index) |

Self-reports |

Established

foundational construct for mental effort measurement |

Post-hoc

bias; lacks real-time granularity |

|

Physiological Approaches Zainuddin et al.

(2020) |

EEG and physiological

measures for cognitive load detection |

EEG (theta-band), HRV |

Demonstrated correlation

between neural activity and working-memory strain |

Requires lab setup; not

scalable for real-time e-learning |

|

Multimedia

Learning Principles Shin (2020) |

Multimedia

Learning Theory (MLT) principles |

Visual

and auditory content |

Proposed

dual-channel, limited-capacity framework for media design |

Static

principles; non-adaptive to learner diversity |

|

Rule-Based Adaptive Systems Barclay et al.

(2021) |

Adaptive dialogue and

affective sensing |

Facial expressions, text

dialogue |

Adjusted instructional

difficulty based on affective cues |

Limited multimodal integration; heuristic rather than learned adaptation |

|

Deep

Learning for Load Estimation Gardner et al. (2021) |

CNN–LSTM

hybrid modeling |

EEG

signals |

High

temporal accuracy in predicting mental effort |

Focused

on single modality; interpretability remains low |

|

Reinforcement-Based

Adaptation Jeun et al. (2022) |

Deep reinforcement learning

for task difficulty regulation |

Performance and behavioral

data |

Improved retention and

engagement through dynamic difficulty adjustment |

No integration with

physiological load measures |

|

Multimodal

Fusion Models Hoorelbeke et al. (2016) |

Attention-based

fusion for cognitive load prediction |

Gaze,

emotion, interaction logs |

Robust

cognitive state prediction under diverse media conditions |

High

computational cost; lacks scalability for large datasets |

The preliminary theoretical sources offered an inventory conceptualization of the measurement of cognitive effort using self-report measures. Although these subjective indices were used as the foundation of the measurement of cognitive load, their dependence upon post-task introspection restricted temporal accuracy and responsiveness Zhai et al. (2024). The further incorporation of physiological indicators signified that it shifted to objective assessment based on data. The neural correlates of working-memory strain were validated using these methods because both EEG spectral bands and heart rate variability (HRV) were related to levels of cognitive effort. But, they mainly were restricted to managed laboratory settings and had no real-time flexibility in dynamic learning settings.

3. AI-Driven Cognitive Load Detection Framework

The suggested AI-Based Cognitive Load Detection Framework creates an integrated construction to integrate principles of cognitive science with the field of computational intelligence to infer and minimize cognitive load in the learning process of multimedia. It takes Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) out of its fixed paradigm of instructional design and turns it into a dynamic, data-driven orchestration system that perceives, interprets and continually responds to the mental state of the learner. The framework combines multimodal sensing, deep learning-based cognitive inference and adaptive feedback loops in a closed system, which guarantees that instructional content changes in accordance with the cognitive processing requirements. The framework is based on a multimodal intelligence engine that gathers the three aspects of cognitive load, intrinsic, extraneous, and germane, by utilizing behavioral, physiological, and contextual data. These signals are processed in real time as the learners engage with multimedia material so as to dynamically estimate and balance cognitive strain. The system is a closed feedback system that includes data acquisition, deep learning-based inference, adaptation by reinforcement learning, and continuous feedback renewal. Such an integrated pipeline allows the real-time monitoring and optimization of the cognitive state of the learner and provides a balanced, adaptive and human oriented learning experience.

Step -1] Multimodal Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

The framework integrates three types of data to provide adequate estimates of cognitive load, including physiological, behavioral, and affective modalities of data. Mental effort Physiological indices of neural and stress-linked activity include EEG, HRV, and GSR, whilst behavioral ones, including mouse movements, density of clicks, and reaction time, indicate engagement and attention. Environmental and affective evidence such as facial expressions, posture and ambient conditions provide supplementary information concerning focus and comfort of the learners. All data streams are filtered, normalized, and time-aligned and divided into short time windows to run deep learning-based sequential algorithms to analyze the changing cognitive states.

Step -2] Cognitive Inference Module Using DEE

The Cognitive Load Inference Engine is based on the hybrid CNN-LSTM model that is trained to learn both space and time patterns of multimodal data. Convolutional layers go on to extract localized features of the signal (i.e. localized activation maps in EEG, clusters of attention in gaze data etc) while the LSTMs address temporal correlation with mental effort over time.

![]()

In which (Xt) is the input being multimodal at time (t) and f 0 is the parameterised neural mapping to the cognitive load categories (low, moderate, high). The loss function is a hybrid of cross-entropy classification and a regularization term, which is defined using physiological coherence to facilitate a constant cross-modal mapping:

![]()

In this case, Eintri,Eextra,and Egerm display the target load estimates based on empirical learning-performance correlations, and the weights (lambda i) are the balance optimization of the three types of loads. Through multimodal training, the engine becomes trained to identify patterns that are associated with particular cognitive conditions, like concentration, confusion, fatigue, and so on, and categorize them as such. This classification is the input of the following process of adaptive orchestration.

Step -3] Reinforcement Learning of Adaptive

Orchestration

The Adaptive Media Orchestrator uses the concept of reinforcement learning (RL) to decide how instructional materials are to be altered in real time in order to maximize the cognitive state of the learner. RL agent is an independent decision-maker, which constantly analyzes the efficiency of adaptation strategies (i.e., changing visual density, switching modalities, breaking things into smaller parts, or simplifying language). A reward function (R t ) is used to control the learning process to ensure cognitive balance:

![]()

Lt Lopt = (Lt) estimated load, (Lopt) is the intended optimal load (a moderate load that does not occur when overloaded), and Ct is the cost of adaptation (e.g. delay, system reconfiguration time). When the learner stays within the optimal zone of cognitive activity, positive rewards are given. With time, the RL agent gets to know state-action policies π(s,a) which reduce extraneous load but maintain germane engagement. This internal control makes the experience of every learner to be unique whose adaptability is in order to their real-time cognitive patterns.

Step -4] Explainability and Human-Artificial

Intelligence Collaboration Layer

The framework uses an Explainable AI (XAI) interface to solve the interpretability gap of the available systems. This layer interprets decisions in the model into pedagogically valuable feedback to learners and instructors. An example of such messages that can be posted by the system includes: high visual load identified, decrease animation complexity; learner demonstrates low germane engagement, include contextual cues. Using a visualization of the connection between perception and response to adaptations, the XAI layer makes AI-mediated learning environments transparent, accountable, and trustworthy.

The educators are provided with a cognitive analytics dashboard where they can observe such major indices as actual (CE=PerformanceEffort) attention stability and content effectiveness indices. It is a two-way interaction channel that creates a symbiotic relationship between human educators and AIs - with the machine maximizing learning flow and educators interpreting and situational contextualizing results.

4. Experimental Setup and Dataset

The experimental design was designed in a manner that would allow the empirical validation of the efficacy of the AI-based Cognitive Load Detection and Adaptive Media Optimization System (AMCOS) when placed within controlled multimedia learning environments. It focused on examining the effect of multimodal AI-assisted inference and adaptive content coordination on the performance, engagement and cognitive efficiency of learners. A detailed table is now included in the section that provides the demographics of the participants, the dataset composition, and sample multimodal statistics to enhance the methodological transparency.

Step- 1] Experiment Design and Objectives

The experiment was based on the mixed-method controlled design, which included quantitative analysis and qualitative analysis to estimate the model accuracy and pedagogical effect. Two study conditions were developed, the Control Group, which applied traditional static multimedia lessons, and Experimental Group, which applied the adaptive AMCOS interface. The participants were given 45 minutes session and post-assessment and self-reported cognitive load surveys:

1) To determine the capability of the AI inference engine to predict cognitive load on the basis of multimodal data streams.

2) To determine whether the adaptive system is effective in enhancing the learning outcomes and cognitive effectiveness over traditional methods.

Step- 2] Respondents and Demographics

One hundred and twenty (120) respondents in undergraduate courses in Computer Science and Multimedia Studies were recruited. Gender and cognitive aptitude were balanced and random in the selection of participants allocated to control (n=60) and experimental (n=60) groups.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Participant Demographics and Group Allocation |

|||

|

Variable |

Control

Group (n = 60) |

Experimental

Group (n = 60) |

Total

(N = 120) |

|

Mean

Age (years) |

20.8

± 1.9 |

21.1

± 2.1 |

21.0

± 2.0 |

|

Gender (Male / Female) |

30 / 30 |

30 / 30 |

60 / 60 |

|

Program

(CS / Multimedia) |

32 /

28 |

31 /

29 |

63 /

57 |

|

Prior Online Learning (Yes) |

45 (75.0%) |

47 (78.3%) |

92 (76.7%) |

|

Mean

WMT Score (0–100) |

68.4

± 7.5 |

69.1

± 7.2 |

68.7

± 7.3 |

Group equivalence in terms of age, academic background and working-memory capacity as summarized in Table 2 is confirmed and internal validity of the comparisons is assured. Both groups were almost identical in terms of mean ages ([?]21 years) and mean Working Memory Test (WMT) scores of almost 69 +- 7, which is consistent with the baseline cognitive ability. Online learning exposure had also been similar before (approximately 77 percent).

Step-3] Configuration of Learning Environment

The experimental sessions were held in a multimedia cognition laboratory that has high-performance workstations, physiological monitoring sensor, adaptive learning modules that run on a local AI server. It was equipped in each workstation:

· EEG Headset (8-channel) for cortical load detection (theta/alpha ratio).

· Eye-Tracking Camera (120 Hz) for fixation and gaze dispersion analysis.

· Facial Emotion Recognition Module using a CNN-based classifier.

· Behavioral Logger capturing scrolls, dwell times, and click patterns.

The AMCOS adaptive learning interface used real-time adjustment of pacing and modality and visual density as load estimates produced by AI. Students were immersed in the same instructional material so that they could be compared to the other groups just that they were adaptive.

Step- 4] Dataset Composition and Temporal Segmentation

About 303 hours of multimodal interaction data were produced through the experiment. All the temporal segments (10 seconds) were annotated based on the level of cognitive load (low, moderate and high) that were proven by the algorithmic and expert annotation. The scope and structure of the data used are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Dataset Composition and Temporal Segmentation |

|||

|

Dataset

Component |

Control

Group |

Experimental

Group |

Total |

|

Number

of Participants |

60 |

60 |

120 |

|

Total Recording Time (hours) |

145 |

158 |

303 |

|

Average

Session Duration (minutes) |

41.2

± 4.7 |

42.0

± 4.3 |

41.6

± 4.5 |

|

Temporal Windows (10 s each) |

52,200 |

56,880 |

1,09,080 |

|

Windows

Labeled “Low Load” |

18,450

(35.3%) |

15,210

(26.7%) |

33,660

(30.8%) |

|

Windows Labeled “Moderate

Load” |

21,390 (41.0%) |

27,030 (47.6%) |

48,420 (44.4%) |

|

Windows

Labeled “High Load” |

12,360

(23.7%) |

14,640

(25.7%) |

27,000

(24.8%) |

|

Train / Validation / Test

Split (win) |

76k / 16k / 17k |

81k / 18k / 18k |

157k / 34k / 35k |

Synchronous EEG, eye tracking, facial affect, and behavior are all part of each temporal segment and have been preprocessed using filters and normative normalisation and time alignment. The output datum constitutes a multimocal corpus that can be trained and used in the analysis of reinforcement adaptation.

Step- 5] Descriptive Multimodal Statistics

In order to study the cognitive behavior trends in varied load conditions, descriptive analyses of aggregated multimodal indicators were carried out. Table 4 presents the sample data to demonstrate the difference in means of physiological, behavioral and affective measures at low, moderate and high loads level.

Table 4

|

Table 4 Sample Descriptive Statistics of Key Multimodal Indicators by Cognitive Load Level |

|||

|

Indicator |

Low

Load (n ≈ 33,000 win) |

Moderate

Load (n ≈ 48,000 win) |

High

Load (n ≈ 27,000 win) |

|

Cognitive

Workload Index (CWI) |

0.34

± 0.09 |

0.57

± 0.11 |

0.81

± 0.08 |

|

Visual Attention Stability

(VAS) |

0.78 ± 0.10 |

0.71 ± 0.12 |

0.63 ± 0.15 |

|

Affective

Valence-Arousal (AVAS) |

0.21

± 0.18 |

0.08

± 0.20 |

-0.19

± 0.22 |

|

Behavioral Engagement Score

(BES) |

0.65 ± 0.14 |

0.72 ± 0.13 |

0.69 ± 0.15 |

|

Mean

Response Latency (s) |

2.8

± 0.9 |

3.6

± 1.1 |

4.5

± 1.4 |

|

Quiz Accuracy (%) |

86.2 ± 5.3 |

82.7 ± 6.4 |

75.9 ± 7.8 |

Table 4 indicates that the higher the level of the cognitive load, the higher the level of CWI and the lower the level of VAS, which agrees with the predictions of CLT. Similarly, with increased load, quiz accuracy decreases confirming the accuracy of the multimodal cognitive load estimation process. The highest level of behavioral engagement is moderate load, which depicts the optimum challenge zone of germane learning.

5. Results and Analysis

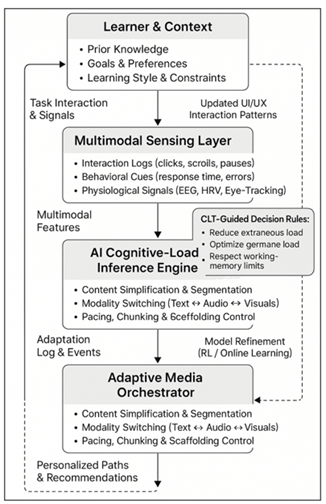

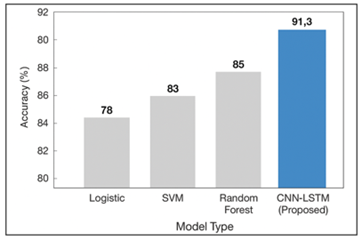

The experimental results are an empirical support of the suggested AI-Driven Cognitive Load Detection and Adaptive Media Optimization System (AMCOS). The comparison is made to provide system performance with baseline methods on three large dimensions, namely, cognitive load detection accuracy, learning gain and cognitive efficiency and physiological-behavioral consistency with different load conditions. The CNN-LSTM multimodal architecture AI inference model demonstrated a detection rate of 91.3 and F1-score of 0.89, which was better than the traditional-based classifiers, including Logistic Regression, SVM, and Rand Forest. The predictions of the model were highly related to self-reported data on cognitive load (r = 0.84, p < 0.001), which supported the claim that multimodal data fusion increased predictive strength.

As Figure 2 shows, the CNN-LSTM model is evidently superior to the traditional algorithms because it is able to analyze both the temporal patterns in EEG, gaze and behavioral data much better than the traditional models.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Cognitive Load Detection Accuracy Across Models

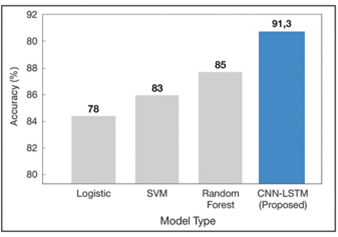

On comparative analysis of the control and experimental groups, there is significant improvement of learning results in AI-mediated conditions. Students who read adaptive material recorded an average learning gain (LG) of 0.34 with a 0.21 average learning gain (LG) in the control group or 62% relative improvement. As Figure 3 demonstrates, cognitive load feedback-based adaptive interventions led to much higher post-test scores, which prove that optimized pacing and media simplification enhanced comprehension.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Learning Gain (LG) Comdparison

Between Groups

Furthermore, Cognitive Efficiency (CE) measure, which the ratio of learning performance to mental effort, increased by almost 27 percent in the experiment group. As depicted in Figure 4, the adaptive system maintained learners in an optimal engagement bandwidth, so that the cognitive resources were distributed reasonably throughout the session period.

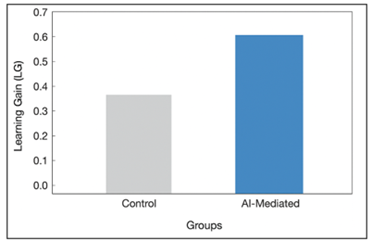

Figure 4

Figure 4 Cognitive Efficiency (CE) Improvement

EEG and gaze data were analyzed in a multimodal way which showed that there is great coherence between Cognitive Workload Index (CWI) and Visual Attention Stability(VAS) measures. CWI rose with the increase in the load levels of the learner between low to high load tasks and VAS dropped between 0.78 and 0.63 indicating the reverse relationship between mental effort and persistent visual attention. This pattern, which is represented in Figure 5 is consistent with predictions of Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) which states that high cognitive demand leads to resource saturation and attention fragmentation.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Physiological and Behavioral

Trends Over Load Levels

The synthesized findings support the fact that the AMCOS model is effective in alleviating cognitive overload and improving germane involvement with the help of adaptive orchestration. Experimental condition learners had a higher comprehension at reduced perceived effort and physiological stability was ensured so that the AI system was able to sustain a cognitive equilibrium during the learning sessions. These findings can be empirically proven to show that AI-based adaptation based on Cognitive Load Theory can make media learning an intelligent and human friendly process that constantly optimizes the mental effort and quality of instructions.

6. Conclusion

This research creates an all-inclusive paradigm of AI-mediated cognitive load mitigation in multimedia learning, combining cognitive science principles with developing machine intelligence. The proposed AI-Driven Cognitive Load Detection and Adaptive Media Optimization System (AMCOS) manages to apply Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) in real-time using the combination of multimodal sensing, deep learning-based inference, and reinforcement learning-based adaptation. The framework proves that cognitive efficiency, as well as learning effectiveness, can be both improved by the means of constant monitoring and adaptive coordination of instructional media. The approach was confirmed to be effective through the experimental findings. CNN-LSTM inference model had 91.3% accuracy in identification of cognitive load, which was higher than the traditional methods, and adaptive interventions had enhanced learning gain by 62% and cognitive efficiency by 27% than the static systems. Physiological and behavioral studies also confirmed that the learners had a good balance of cognition by having a stable attention and less overload. These practical results support the theoretical assumption about AI as a cognitive controller, which can dynamically adjust the complexity of instructions to the learning abilities of a person. The overall contribution of the study is to close the gap in understanding between educational psychology and computational intelligence that has been existing long before the study. Instructing machine learning pipelines with CLT-guided interpretability enables AMCOS to adapt to instructions besides explaining its choices in pedagogically significant fashions. Such transparency builds human-AI cooperation and builds trust on adaptive learning technologies. Finally, the study proposes a research roadmap to smart, human-focused education systems that can perceive, predict, and optimize cognition of learners.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Barclay, I., Taylor, H., Preece, A., Taylor, I., Verma, D., and de Mel, G. (2021). A Framework for Fostering Transparency in Shared Artificial Intelligence Models by Increasing Visibility of Contributions. Concurrency and Computation: Practice and Experience, 33(19), e6129. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpe.6129

Firth, J., Torous, J., Stubbs, B., Firth, J. A., Steiner, G. Z., Smith, L., and Sarris, J. (2019). The “Online Brain”: How the Internet may be Changing our Cognition. World Psychiatry, 18(2), 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20617

Gardner, J., O’Leary, M., and Yuan, L. (2021). Artificial Intelligence in Educational Assessment: “Breakthrough? Or Buncombe and Ballyhoo?” Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 37(5), 1207–1216. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12577

Hoorelbeke, K., Koster, E. H. W., Demeyer, I., Loeys, T., and Vanderhasselt, M.-A. (2016). Effects of Cognitive Control Training on the Dynamics of (mal)Adaptive Emotion Regulation in Daily Life. Emotion, 16(7), 945–956. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000169

Hung, H.-C., Liu, I.-F., Liang, C.-T., and Su, Y.-S. (2020). Applying Educational Data Mining to Explore Students’ Learning Patterns in the Flipped Learning Approach for Coding Education. Symmetry, 12(2), 213. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12020213

Hwang, G.-J., Sung, H.-Y., Chang, S.-C., and Huang, X.-C. (2020). A Fuzzy Expert System-Based Adaptive Learning Approach to Improving Students’ Learning Performances by Considering Affective and Cognitive Factors. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 1, 100003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2020.100003

Jeun, Y. J., Nam, Y., Lee, S. A., and Park, J.-H. (2022). Effects of Personalized Cognitive Training with the Machine Learning Algorithm on Neural Efficiency in Healthy Younger Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13044. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013044

Jones, J. S., Milton, F., Mostazir, M., and Adlam, A. R. (2019). The Academic Outcomes of Working Memory and Metacognitive Strategy Training in Children: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Developmental Science, 23(1), e12870. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12870

Khosravi, H., Sadiq, S., and Gašević, D. (2020). Development and Adoption of an Adaptive Learning System. In Proceedings of the 51st ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education (1052–1058). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3328778.3366900

Lazer, D. M. J., Baum, M. A., Benkler, Y., Berinsky, A. J., Greenhill, K. M., Menczer, F., Metzger, M. J., Nyhan, B., Pennycook, G., Rothschild, D., and Others. (2018). The Science of Fake News. Science, 359(6380), 1094–1096. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao2998

Martin, F., Chen, Y., Moore, R. L., and Westine, C. D. (2020). Systematic Review of Adaptive Learning Research Designs, Context, Strategies, and Technologies from 2009 to 2018. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68, 1903–1929. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09793-2

Shin, D. (2020). User Perceptions of Algorithmic Decisions in the Personalized AI System: Perceptual Evaluation of Fairness, Accountability, Transparency, and Explainability. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 64(4), 541–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2020.1843357

Tsai, F. S., Lin, C. H., Lin, J. L., Lu, I. P., and Nugroho, A. (2018). Generational Diversity, Overconfidence and Decision-Making in Family Business: A Knowledge Heterogeneity Perspective. Asia Pacific Management Review, 23(1), 53–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2017.02.001

Zainuddin, Z., Shujahat, M., Haruna, H., and Chu, S. K. W. (2020). The Role of Gamified E-Quizzes on Student Learning and Engagement: An Interactive Gamification Solution for a Formative Assessment System. Computers and Education, 145, 103729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103729

Zhai, C., Wibowo, S., and Li, L. D. (2024). The Effects of Over-Reliance on AI Dialogue Systems on Students’ Cognitive Abilities: A Systematic Review. Smart Learning Environments, 11, 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-024-00316-7

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.