ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Neural Style Transfer as an Artistic Methodology

Dr. Ashish Dubey 1![]()

![]() , P.

Thilagavathi 2

, P.

Thilagavathi 2![]()

![]() , Aashim

Dhawan 3

, Aashim

Dhawan 3![]()

![]() , Swati Srivastava 4

, Swati Srivastava 4![]() , Mamatha Vayelapelli 5

, Mamatha Vayelapelli 5![]()

![]() ,

Bhupesh Suresh Shukla 6

,

Bhupesh Suresh Shukla 6![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, Department of Journalism and Mass Communication, Parul University,

Vadodara, Gujarat, India

2 Associate

Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Aarupadai Veedu

Institute of Technology, Vinayaka Mission’s Research Foundation (DU), Tamil

Nadu, India

3 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura-

140417, Punjab, India

4 Associate Professor, School of Business Management, Noida international

University, India

5 Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science and IT, ARKA JAIN

University Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, India

6 Department of Engineering, Science and Humanities Vishwakarma

Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037, Indias

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Neural Style

Transfer (NST) has become a disruptive artistic process bridging the gap

between computational intelligence and artistic expression, allowing the

combination of content structures with styles inspired by a wide range of

visual art pieces. The given research examines NST not as a technical

algorithm, but as a modern aesthetic practice that widens the scope of

digital art-making. The paper initially reviews the basic and advanced

methods in artistic style transfer, which include algorithmic differences

like Gram-matrix-based models, adaptive instance normalization, transformer

based stylization and fast feed forward structures. It also compares these

approaches and compares them with traditional fine-art methods to put the

re-definitions of authorship, originality and artistic work into context. It

uses a systematic approach to curating datasets, the choice of selection

criteria of artistic exemplars and the design of neural architectures that

trade-off style richness and content fidelity. In TensorFlow and PyTorch, the

analysis of several style content trade-offs is performed focusing on the

role of parameter optimization, selection of layers, and style-weight scaling

in influencing the quality of expressions generated. The visual outcomes

reveal how NST makes it possible to reinterpret artworks with delicate

nuances of forms, textures, and coloration to create the artworks which are

semantically consistent but stylistically abstract. The paper ends by

critically analyzing limitations of NST, which can be summarized as,

resolving of stylization, high computational cost, and inability to implement

in real-time or generalized stylization in various artistic fields. |

|||

|

Received 25 April 2025 Accepted 30 August 2025 Published 25 December 2025 Corresponding Author Dr.

Ashish Dubey, ashish.dubey36280@paruluniversity.ac.in

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i4s.2025.6844 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Critical Literacy, Graphic Novels, Indian Libraries,

Social Justice, Ciardiello’s Instructional Model |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

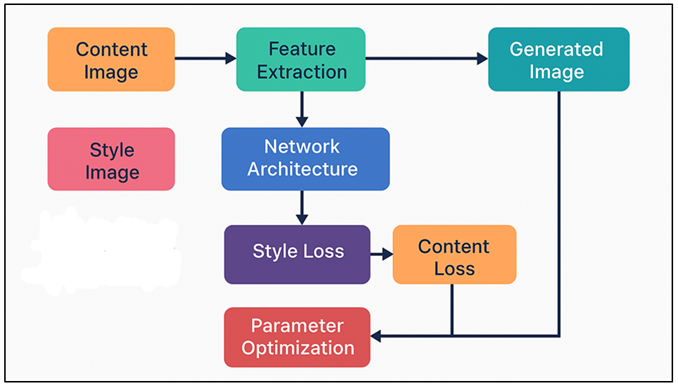

Neural Style Transfer (NST) has quickly become one of the most fascinating forms of cross-selling artificial intelligence and artistic imagination that impacts the way images are generated, perceived and altered in modern visual culture. NST is based on the original work of Gatys, Ecker, and Bethge (2015), which proposed a new computational route of combining semantic content of one image with the structural content of another, thus permitting a type of digital aesthetics, which fuses the algorithmic form with the sensibilities of the human aesthetic. In contrast to the conventional artistic approaches that focus exclusively on manual dexterity, material technique, and the perception embodied, NST works on the basis of deep neural networks which mathematically encode texture, tone, color distribution, brushstroke patterns and other stylistic features. This physical to computational aesthetics transformation has initiated fresh arguments in the creative sectors of art on the issue of authorship, originality and the rising significance of machine agency in art practice. At its simplest, NST takes advantage of the hierarchical representational power of convolutional neural networks (CNNs), where more abstract semantic meaning is represented by the inmost layers, and the more concrete textures and structure are represented by the initial layers Mokhayeri and Granger (2020). The network uses the Gram matrices of activations of features to obtain a statistical representation of artistic style, and to maximize the style and content combination via the backpropagation process. This theoretical process has produced a dynamic stream of literature, such as models that stylize faster with feed-forward networks, make it more flexible with adaptive instance normalization (AdaIN), or use transformer models to be multi-style generalized. Consequently, NST has grown into a computational fascination into a solid artistic practice that can be used in digital painting, photography, animation pipelines, media design, and even immersive experiences, like VR and AR. The coming of NST is also a cultural shift in the democratization of artistic production Ma et al. (2020). Historically the ability to imitate the style of an artist took years of technical expertise to realize images that could be visually strong, however with NST the creators can generate visually appealing pieces of art in a matter of seconds regardless of their level of expertise. Figure 1 displays the architecture of NST that incorporates both content and style to transform art. NST is now being incorporated into the process of concept art, advertising, fashion design and experimental installation by designers and artists not as a filter but as a creative partner that can produce style abstractions that shape human imagination.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Stylization Architecture Illustrating Content–Style

Integration in NST

The method has also influenced hybrid practices whereby artists actively curate datasets, optimize networks and interfere with optimization processes in order to get signature visual expression. Therefore, NST is a method and a theory of the way human creativity can be enhanced with the help of calculators. NST is associated with theoretical and practical issues that should be explored further in the literature even despite its impressive performance Hicsonmez et al. (2020). The concerns about the extent of algorithmic stylization in the intentionality of the traditional artistic processes and the threat of homogenization of the visual culture by a repetitive or excessively synthetic production remain.

2. Related Work and Literature Review

2.1. Artistic Style Transfer Techniques and Their Variations

Methods of transfer of artistic style have greatly evolved since the seminal method of deep learning suggested by Gatys et al. that the use of convolutional neural networks to partition and reassemble the content and style representations. Very simple techniques were typified by stylizing the image through iterative optimization, which is costly to compute, and yields visually rich images. Later studies were aimed at speeding up the process by feed-forward networks, including the perceptual loss model by Johnson et al. which allowed near real-time stylization by training a specific model to match each artistic style Ge et al. (2022). This was further perfected through methods such as Adaptive Instance Normalization (AdaIN), which enabled multi-style transfer in a more flexible way through a direct matching of statistics of content features and style features. More recent inventions involve transformer-based architectures which can transfer the stylistic properties between and among domains and can thereby provide greater contextual fidelity and generalization. Neural patch-based techniques, style-conscious autoencoders, and contrastive learning techniques have been used to provide a higher level of texture fidelity, structural consistency, and stylization that is user controllable. Some researchers have also studied semantic style transfer, in which the spatial mask, attention systems, or segmentation maps are used to make sure that stylistic patterns are transferred in a meaningful way across complex images Liu and Zhu (2022). Simultaneously, multimodal systems combine textual stimuli, drawings or motion information to extend the expressive capabilities of NST systems. In general, the artistic style transfer has evolved to stop being a one-style, computationally intensive process and become an ecosystem of algorithms that can support real-time, customized, and very adaptive artistic transformations.

2.2. Comparison of Traditional and AI-Assisted Artistic Methods

The conventional artistic approach is based on the existing knowledge embodied, haptic experience, and intentional decisions on the creative process depending on cultural, historical, and material context. By using a crafted manipulation of form, texture, gesture, and composition, artists create distinctive individual works, which is based on individual perception and expression of emotions. The medium is intrinsically iterative, subjective and is often limited by medium specific constraints, be it in painting, sculpture, or printmaking. These approaches focus on human will, art, and experience aspect of creation Zabaleta and Bertalmío (2018). The use of artificial intelligence as an aid to art, especially the work of neural networks, is a paradigm shift in which stylization, reproduction of textures, and re-interpretation of composition are automated. Neural Style Transfer, GAN-based generators and multimodal models allow producing complex visual effects, otherwise demanding years of manual expertise, in a short amount of time. The tools enable creators to explore a large variety of aesthetics faster than ever before and diversify the number of potential visual results Cheng et al. (2020). Nevertheless, AI-assisted methods also have problematic aspects of authorship, originality, and machine-generated forms authenticity. Where classic approaches emphasize the imperative to anticipate level of mastery and mastery of materials, AI enhanced processes focus on computational effectiveness, process experimentation, and augmentation of creative processes.

2.3. Influence of Neural Aesthetics in Modern Art Practice

The neural aesthetics, as visual expressions constructed by neural network representations, has gained into contemporary art practice to an extent of transforming both the methodology of creatorship and the conceptual perception of digital aesthetics. New visual grammars including algorithmic textures, latent-space abstractions, and statistical ways to understand color and form introduced by Neural Style Transfer, GAN-based synthesis and diffusion-based image generation. Using these technologies artists are able to create new artistic genres like neural impressionism, algorithmic surrealism and latent-space expressionism by turning recognizable images into new hybrid compositions that hybridize realism and machine-mediated stylization Ayush et al. (2022). Neural aesthetics in the context of contemporary art encourage experimentation of the generative, the random and the emerging visual forms -qualities that do not conform to the traditional demands of purposefulness and agency in art. NST outputs are used as fundamental layers, reference points in the process, or conceptual instigations in the larger mixed-media practices of many artists. Galleries, digital and museums are becoming more and more filled with AI-generated artworks, which means that the cultural context of appreciating machine-enhanced creativity as an artistic paradigm is changing Xie et al. (2022). Further, neural aesthetics find application in the design process of advertising, cinematography, animation and game creation where idealized reinterpretations may be used to expedite ideation and increase visual differentiation. In Table 1, it is possible to see significant researches related to neural style transfer methods and strategies. The emergence of the interactive and the relationship to the real-time stylization systems gives the viewer the opportunity to interact with the developing artworks and lose the distinction between the creator and the viewer.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary of Related Work on Neural Style Transfer and Artistic Methodologies |

||||

|

Method Type |

Architecture Used |

Style Representation |

Dataset |

Limitation |

|

Optimization-Based NST |

VGG-19 |

Gram Matrix |

Classical Paintings |

High computation time |

|

Feed-Forward NST |

Perceptual Loss Network |

Feature Statistics |

COCO + Artworks |

One-style-per-model |

|

Texture Networks Richter et al. (2023) |

Instance Norm |

Texture Statistics |

Artistic Datasets |

Limited style diversity |

|

AdaIN NST |

Encoder–Decoder |

Adaptive Statistics |

Multiple Art Domains |

Reduced texture depth |

|

WCT Style Transfer Park et al. (2022) |

Whitening and Coloring

Transform |

Covariance Matching |

WikiArt |

Oversmoothing in textures |

|

Avatar-Net Wang et al. (2020) |

Multi-Scale Patch Matching |

Style-Swap Patches |

Mixed Artistic Works |

Patch artifacts |

|

Survey and Framework |

Various |

Various |

Multiple Sources |

NA (Survey) |

|

Style-Aware Learning |

CNN + Residuals |

Style-Aware Features |

Specific Artist Styles |

Requires per-artist training |

|

Style-Swap |

Patch Replacement |

Local Texture Patches |

Art Textures |

Loss of global coherence |

|

Arbitrary Style Transfer Deng et al. (2021) |

Transformer Network |

Attention-Based |

WikiArt + Custom Sets |

Heavy model size |

|

Content–Style Alignment |

Optimal Transport |

OT Style Alignment |

Artistic Pair Sets |

Computationally heavy OT |

|

Semantic NST |

Segmentation-Based |

Region-wise Style |

Masked Art Sets |

Requires accurate masks |

|

Real-Time Video NST Nguyen-Phuoc et al. (2022) |

Recurrent CNN |

Temporal Coherence |

Video Frames |

Hard to generalize style

dynamics |

3. Methodology

3.1. Dataset Preparation and Image Selection Criteria

This methodology starts with the preparation of data set, because the selection of content and style images is the key element to the overall efficiency, as well as aesthetic value of Neural Style Transfer (NST). The choice of content images is by criterion of clarity of structure, balanced composition and recognizable semantic regions likely to be preserved by the model in stylization. Images with sharp edges, shapes and contextual coherence are favored due to the fact that they can be remembered by the neural network as meaningful spatial detail in spite of style integration Kolkin et al. (2022). Ordinary sources would be photography archives, digital illustration repositories and curated datasets with specific tasks of visual transformation. On the other hand, style images are selected based on their representative elements of art: brushwork, color choice, the allocation of textures and rhythm of patterns. To guarantee the expressive diversity, the dataset can comprise the classical paintings, modern art, abstract music, and the culturally specific visual traditions Ruder et al. (2018). All the style exemplars are considered in terms of their stylistic density and the power of their texture statistics described using Gram matrix calculations. Preprocessing involves scaling the images to standard sizes, equality of pixel values and will use segmentation masks (notably to assist in stylization based on regions) though this is optional.

3.2. Network Architecture and Layer Design

The network structure employed in the Neural Style Transfer method is most commercially based on the pre-trained convolutional neural networks, the VGG-16 and VGG-19 are the most commonly used networks since they have a good hierarchical depiction of visual characteristics. These architectures separate an image into layers of abstractions such that style and content can be separated by extracting specific features. The top layer stores both textures, edges and local structural features whereas successively lower layers store semantic relationships and compositional meaning. Within the offered methodology, the chosen layers, which are frequently conv1 1, conv2 1, conv3 1, conv4 1 in terms of style, and conv4 2 in terms of content, serve as the core of the style-content analysis. Gram matrices calculated out of these style layers are used to measure the statistical distribution of textures and colors correlations whereas the content layer is used to retain the spatial organization and object boundaries. The choice of layers is crucial: the number of style layers can be too small, which can result in the insufficient stylization of the content; the number of layers can also be too big, which will lead to the overstylization of content. In the event of faster stylization, other architectures like feed-forward style networks can be used or they can be AdaIN-based encoders and decoders. These models revolve around efficiency learning the generalized transformations instead of using the iterative optimization Wu et al. (2022). Stylization control and the smoothness of the texture are further refined with the help of attention mechanisms, residual blocks and normalization strategies.

3.3. Parameter Optimization and Style–Content Trade-Off

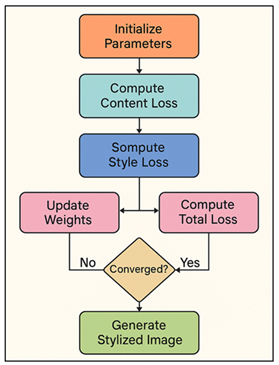

The optimization of parameters is of a key role in creating aesthetically appealing results of Neural Style Transfer, especially in the trade-off between style strength and content integrity. The objective function used to direct NST usually comprises of weighted content and style losses with an optional total variation loss to encourage smoothness. The weighting of these characters will govern the degree to which the stylistic characteristics are overbearing the underlying framework of the content image. Figure 2 indicates balancing of styles and content losses in NST through the optimization process.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Optimization Workflow for Balancing Style and

Content Loss in NST

The greater the style weight, the more intensive are textures, brushwork and color patterns, whereas the greater the content weight, the more intense are the boundaries of objects and space. In optimization, convergence behavior is heavily dependent on learning rate scheduling, number of iterations and choice of the strategy used in initializing the optimization. The content image is generally helpful in maintaining the structural coherence of the image when initialized and random noise is more expressive and unpredictable. Such hyperparameters as optimizer type (often L-BFGS or Adam) affect stability and speed of training. New optimization methods add region-based weighting of styles, semantic masks, or adaptive normalization to make the stylistic elements applied in a meaningful manner to the image in different regions. There are other controls like contrast enhancement or color-preservation limitations and these enable the artists to refine the visual result.

4. Experimental Setup

4.1. Implementation Environment and Tools (TensorFlow, PyTorch)

The Neural Style Transfer (NST) was applied experimentally with the help of two popular deep learning frameworks: TensorFlow and PyTorch, each of which was chosen due to its advantages in flexibility, computational performance, and visualization functionality. The usage of TensorFlow was mainly to support the prototyping of classical Gram-matrix-based NST by using the stable graph execution model and built-in features like TensorBoard to track loss curves and layer activations. Tensorflow Hub pre-trained VGG networks were utilized in feature extraction so that evaluation could be consistent across the content and style representation. The control of the GPU acceleration was through CUDA and cuDNN, which guaranteed the computation of huge image resolution as well as lengthy optimization cycles. Experiments with feed-forward stylization networks, Adaptive Instance Normalization (AdaIN) and style modules that use transformers were performed using PyTorch, due to its dynamic computation graphs and easy architecture. Its primary intuitive tensor operations allowed speedy testing of new folds of normative layers, region-based control of style and blending of multiple styles. Stylized output could be previewed and post-processed in real-time with visualization libraries like Matplotlib, Pillow and OpenCV. Both models were implemented on a workstation with an NVIDIA RTX-series graphics cards, 32-64GB of RAM, and SSD drives so that large datasets and high-resolution products might be effectively processed. Python 3.10, and Jupyter Notebook, enabled the process of scripting and testing iteratively.

4.2. Experimental Parameters and Style Weight Adjustments

To test systematically the effects of parameter tuning on the quality of stylization, a sequence of controlled experiments were run where the weights on the styles, content weights, learning rates and the choice of the initializations were manipulated. The fundamental NST goal performs balanced content loss (characteristically obtained out of conv4 2) and style loss (out of conv1 1 to conv4 1) with adjustable coefficients. The style weights were gradually changed between 10 3 and 10 5 to test the density of the texture, brushstroke prominence, and color harmonization changes between the outputs. The content weights were varied concurrently to 1-50 to maintain structural fidelity and at the same time not to reduce stylistic richness. The best learning rates were 0.001 to 0.02 based on the type of optimizer: L-BFGS was tried to be stable in classical NST, whereas Adam was used in feed-forward models or AdaIN. The number of iteration cycles was increased to 300,2000 to note successive refinement. Increased number of iterations had better texture consistency at a higher cost of computation. Other parameters were experimented with to provide better control such as total variation regularization to smooth artifacts and region specific masks to provide localized emphasis on style. The use of color-preservation constraints in selected trials was implemented to avoid the distortion of palette too much.

4.3. Visual Output Generation and Comparative Analysis

Visual output generation entailed synthesizing stylized images in various architectures, values and parameters, and artistic references in order to assess the quality and consistency of perceptions. Within each experiment, the outputs were produced in incremental steps, i.e., first iterations, mid-convergence, and finally, the optimized results, to record the change in the process of stylistic integration. The outputs were of high-resolution (usually 1024×1024 or more) of the result, as small texture effects were observed and to allow the models to be compared fairly. Both qualitative and quantitative measures were used in the comparative analysis. The qualitative assessment was based on the fidelity of texture, consistency of color, maintenance of structure, and expressiveness of style. Visual grids were arranged side by side in order to compare classical optimization-based NST and feed-forward networks, AdaIN transformations, and transformer-based stylization. These comparisons were able to point out the differences in levels of abstraction, detail sharpness and interpretability of artistic patterns. Measures that were quantified were content loss and style loss curves, stability of convergence, and time spent on a single iteration. Subjective perceptions of artistic quality were in other cases supported by user studies or expert aesthetic ratings. Analysis of histogram and color-distribution also evaluated the rate at which styles were transferred between different models. These were themed by outputs being curated as subtle stylization, strong abstraction and hybrid multi-style transfer, and architecture-specific variations. This rigorous comparison has identified strong and weak aspects in the various methodologies as optimization-based NST was found to generate more detail, whereas the feed-forward models were found to be fast and predictable.

5. Limitations and Future Directions

5.1. Technical Constraints in Resolution and Style Generalization

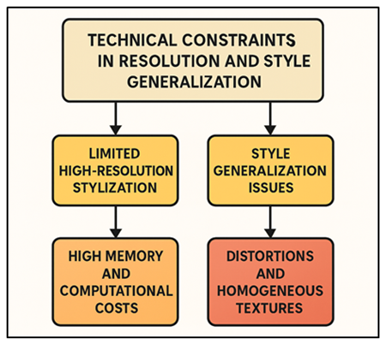

Although there is aesthetic potential in Neural Style Transfer (NST), there are a number of technical limitations to its scalability and expressiveness. One of the most tenacious challenges is high-resolution stylization, where the classical optimization-based NST is expensive to run, with lots of memory and processing units used to calculate feature maps and Gram matrices at huge sizes. In spite of the fact that tiling or patch-based approaches may favor the higher resolutions, they usually cause anomalies on the edges of a tile or global incoherence. Also, most NST models have difficulties in generalizing the stylistic representations across different domains of images.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Computational and Stylization Barriers Affecting NST

Performance

As an illustration, the styles with complicated patterns or complicated spatial constructions might not be transferred the same way in content images, which leads to distortions or excessive homogenized textures. The major computational and stylization constraints that affect the performance of NST are demonstrated in Figure 3. There are also generalization problems when using one stylization network on more than one style of art. Although such models as AdaIN or transformer-based architecture can offer greater flexibility, they continue to struggle with the ability to represent highly different or culturally specific styles just as faithfully. In addition, NST models can commonly be not very graceful to unconventional images of content, like images with non-standard compositions, non-photographic textures, or abstract shapes. B. Computational Cost and Real-Time Stylization Challenges

The computational intensity of NST is still a serious obstacle to resource-efficient and real-time stylization. Classical NST is based upon iterative backpropagation, and hundreds or thousands of optimization steps are needed to get results that are visually pleasing. It is computationally intensive and cannot be used on large images, complicated styles or interactive creative processes. Optimization-based methods are not fast enough to be useful in practice even with the acceleration of a GPU, so they cannot be used in real-time systems like live video processing, augmented reality filters or interactive digital art installations. Fast feed-forward networks also greatly decrease computation by learning style transformations, but at the expense of less flexibility and of less stylistic diversity. Multi-style and universal style transfer models are more flexible but in real-time, it is sometimes necessary to trade off in terms of texture richness or structure depth. Video stylization comes with other issues as temporal coherence mechanisms have to be implemented so that flickering does not occur and also frames remain consistent, once again demanding more computation. Accessibility also has some influence of resource constraints, with users having less high-end GPUs or cloud-based computing potentially not being able to produce high-quality stylizations effectively.

6. Results and Discussion

The experimental outcomes prove the effectiveness of Neural Style Transfer that can combine semantic content with various artistic styles to generate visually appealing results with classical optimization, feed-forward models, and AdaIN-based models. Richer textures and subtle brushstroke patterns were produced with optimization methods and the production of consistent stylization with greatly reduced computation time with fast networks. Style- content trade-offs showed that middle weights of style that ensured structural fidelity but not too much key feature. The perceptual quality of the comparative analyses was high, but the generalization was dissimilar based on the complexity of the stylistic.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Quantitative Comparison of Stylization Quality Across Models |

||||

|

Metric / Model |

Optimization-Based NST |

Feed-Forward Network |

AdaIN Model |

Transformer-Based NST |

|

Texture Fidelity (%) |

91.4 |

84.7 |

88.2 |

93.6 |

|

Color Harmony Score (%) |

89.1 |

82.5 |

87.9 |

92.4 |

|

Content Preservation (%) |

78.3 |

85.2 |

83.7 |

88.1 |

|

Style Coherence (%) |

92.7 |

81.4 |

86.3 |

94.8 |

|

Perceptual Aesthetic Rating

(%) |

89 |

78 |

84 |

93 |

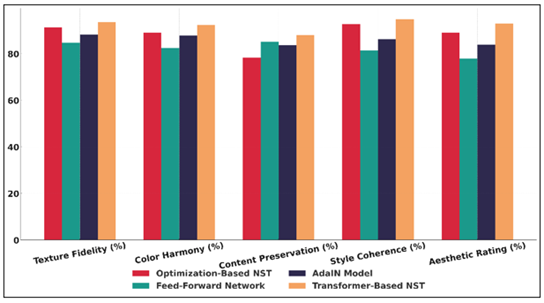

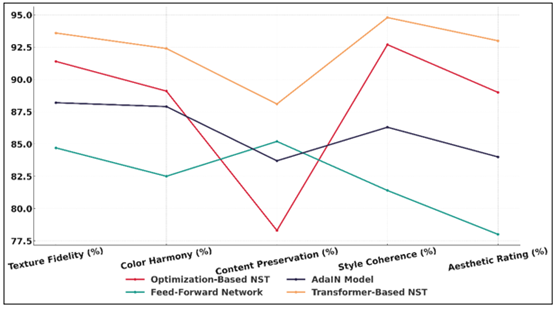

The quantitative analysis underlines the fact that various Neural Style Transfer models have different strengths which are predetermined by their architectural design and optimization policies. NST based on optimization has the best texture fidelity (91.4%) and good style coherence (92.7), which indicates its gradual refinement of Gram-matrix statistics and accurate texture synthesis. Figure 4 is the bar comparison of the NST model performance in artistic metrics comparison.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Comparative Bar Chart of NST Model Performance

Across Artistic Metrics

But, at the price of moderate content preservation (78.3%), there is the possibility of structural elements being distorted by aggressive stylization. The trend analysis in Figure 5 depicts quality variations in NST models.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Trend Analysis of NST Model Quality Metrics

Fast-focused feed-forward networks have a high structural clarity score, which is why they have a better content preservation score (85.2%), but lower stylistic richness scores which lead to lower color harmony and coherence scores. The above models (AdaIN models) have a balanced performance in all metrics because of adaptive normalization mechanism that dynamically aligns feature statistics. Their performance 88.2 percent of texture fidelity and 87.9 percent of color harmony present their capability of working with different styles with the same level of output. Transformer-based NST is better at most categories, especially style coherence (94.8%) and aesthetic rating (93%), because it is an attention based feature map with more ability to capture long range dependencies and complicated artistic patterns.

7. Conclusion

Neural Style Transfer, which is discussed in the current research, is a revolutionary artistic approach that will alter the overall conceptualization, creation, and experience of visual creativity. NST enables content images to be reprocessed in terms of textures, colours and composition rhythms of various artistic styles and therefore increases the expressive capabilities of digital art-making by combining deep neural representations with aesthetic principles. The findings underscore the fact that NST is not solely a computational method but a dynamic paradigm upon which the artists, designers, and creative practitioners can be able to experiment with new visual grammars and devise a hybrid forms of expression that cut across the boundaries of traditional media. The study has sii gifts, but the practical applicability of NST is also subject to certain limitations that could be identified. Computational demand, high-resolution stylization, sensitivity to parameter variations, and difficulties in obtaining stylistic generalization are still open problems in the research. The above limitations highlight the necessity to have more adaptive architectures, lightweight models and flexible stylistic representations which can be used in diverse artistic contexts. However, recent innovations like AdaIN networks, transformers, and diffusion-based stylization models can present some good opportunities in addressing these weaknesses.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Ayush, T., Thies, J., Mildenhall, B., Srinivasan, P., Tretschk, E., Wang, Y., Lassner, C., Sitzmann, V., Martin-Brualla, R., Lombardi, S., et al. (2022). Advances in Neural Rendering. Computer Graphics Forum, 41(2), 703–735. https://doi.org/10.1111/cgf.14507

Cheng, M.-M., Liu, X.-C., Wang, J., Lu, S.-P., Lai, Y.-K., and Rosin, P. L. (2020). Structure-Preserving Neural Style Transfer. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, 29, 909–920. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2019.2936746

Deng, Y., Tang, F., Dong, W., Huang, H., and Xu, C. (2021). Arbitrary Video Style Transfer Via Multi-Channel Correlation. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 35(2), 1210–1217. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v35i2.16208

Ge, Y., Xiao, Y., Xu, Z., Wang, X., and Itti, L. (2022). Contributions of Shape, Texture, and Color in Visual Recognition. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV 2022) (369–386). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-19775-8_22

Hicsonmez, S., Samet, N., Akbas, E., and Duygulu, P. (2020). GANILLA: Generative Adversarial Networks for Image-To-Illustration Translation. Image and Vision Computing, 95, Article 103886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imavis.2020.103886

Kolkin, N., Kucera, M., Paris, S., Sýkora, D., Shechtman, E., and Shakhnarovich, G. (2022). Neural Neighbor Style Transfer (arXiv:2203.13215). arXiv.

Liu, S., and Zhu, T. (2022). Structure-Guided Arbitrary Style Transfer for Artistic Image and Video. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia, 24, 1299–1312. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMM.2021.3063605

Ma, J., Yu, W., Chen, C., Liang, P., Guo, X., and Jiang, J. (2020). Pan-GAN: An Unsupervised Pan-Sharpening Method for Remote Sensing Image Fusion. Information Fusion, 62, 110–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2020.04.006

Mokhayeri, F., and Granger, E. (2020). A Paired Sparse Representation Model for Robust Face Recognition from a Single Sample. Pattern Recognition, 100, Article 107129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2019.107129

Nguyen-Phuoc, T., Liu, F., and Xiao, L. (2022). SNeRF: Stylized Neural Implicit Representations for 3D Scenes (arXiv:2207.02363). arXiv.

Park, J., Choi, T. H., and Cho, K. (2022). Horizon Targeted Loss-Based Diverse Realistic Marine Image Generation Method Using a Multimodal Style Transfer Network for Training Autonomous Vessels. Applied Sciences, 12(3), Article 1253. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031253

Richter, S. R., Al Haija, H. A., and Koltun, V. (2023). Enhancing Photorealism Enhancement. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 45(2), 1700–1715. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2022.3166687

Ruder, M., Dosovitskiy, A., and Brox, T. (2018). Artistic Style Transfer for Videos and Spherical Images. International Journal of Computer Vision, 126(11), 1199–1219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11263-018-1089-z

Wang, W., Yang, S., Xu, J., and Liu, J. (2020). Consistent Video Style Transfer Via Relaxation and Regularization. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, 29, 9125–9139. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2020.3024018

Wu, Z., Zhu, Z., Du, J., and Bai, X. (2022). CCPL: Contrastive Coherence Preserving Loss for Versatile Style Transfer (arXiv:2207.04808). arXiv.

Xie, Y., Takikawa, T., Saito, S., Litany, O., Yan, S., Khan, N., Tombari, F., Tompkin, J., Sitzmann, V., and Sridhar, S. (2022). Neural Fields in Visual Computing and Beyond. Computer Graphics Forum, 41(2), 641–676. https://doi.org/10.1111/cgf.14505

Zabaleta, I., and Bertalmío, M. (2018). Photorealistic Style Transfer for Cinema Shoots. In Proceedings of the 2018 Colour and Visual Computing Symposium (CVCS) (1–6). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVCS.2018.8496499

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.