ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Evaluating AI-Generated Images in Fine Art Education

Anup Kumar Singh 1![]()

![]() ,

Vasanth Kumar Vadivelu 2

,

Vasanth Kumar Vadivelu 2![]() , Kalpana Rawat 3

, Kalpana Rawat 3![]() , K. France 4

, K. France 4![]()

![]() , Dr. Prabhat Kumar Sahu 5

, Dr. Prabhat Kumar Sahu 5![]()

![]() , Saksham Sood 6

, Saksham Sood 6![]()

![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, Department of Fashion Design, ARKA JAIN University Jamshedpur,

Jharkhand, India

2 Department

of Information Technology Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune,

Maharashtra, 411037, India

3 Assistant Professor, School of Business Management, Noida International

University, India

4 Associate Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Aarupadai Veedu Institute of Technology, Vinayaka Mission’s

Research Foundation (DU), Tamil Nadu, India

5 Associate Professor, Department of Computer Science and Information

Technology, Siksha 'O' Anusandhan (Deemed to be

University), Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

6 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura-

140417, Punjab, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

This paper

discusses the ways in which AI image-generation software, including DALL•E,

Midjourney and Stable Diffusion can be assessed and used in art-learning

contexts successfully. The study deals with a significant gap in the

comprehension: although AI systems can create aesthetically vivid images,

their educative, artistic authenticity, and the effect they have on the

creative imagination of students is a poorly studied issue. In the form of a

mixed-method approach, the research gathers both numerical metrics of

performance and anecdotal insights of art teachers, learners, and digital

media professionals. The four main criteria of the evaluation of the

AI-generated artworks include originality, expressiveness, technical polish,

and emotional impact. Based on the constructivist theory of learning, the

aesthetic evaluation traditions, and the new model of human and computer

co-creativity, the research examines how learners engage with, evaluate, and

develop AI-enabled outputs in the studio practice. The experimental modules

created to work in the context of a fine-art classroom indicate that AI tools

have the potential to increase ideation speed, increase visual

experimentation, and assist multimodal aesthetical

thinking. Nevertheless, it is also shown that there are strains on

authorship, dependence on automated output, and critical digital literacy is

required. The comparative analysis shows that there are significant

differences in perception of human-made and AI-generated art, especially in

such aspects as narrative purpose and perceived genuineness. |

|||

|

Received 06 April 2025 Accepted 11 August 2025 Published 25 December 2025 Corresponding Author Anup

Kumar Singh, anup.s@arkajainuniversity.ac.in

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i4s.2025.6840 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: AI-Generated Imagery, Fine Art Education, Aesthetic

Evaluation, Human–Computer Co-Creativity, Generative Models, Digital Pedagogy |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The advent of AI in the creative fields has radically changed the way visual culture is made, perceived and learned. It is now possible to produce high-quality images with textual prompts or sparse visual input due to the rapid development of generative models: GANs, diffusion systems, transformer-based architectures, and so on. The technological change contests the traditional beliefs about the work of art, originality, and aesthetic tastes, and makes educators redefine the way creative abilities would be developed in the classroom. Students can find and discover visual concepts that are complex through AI-generated image tools such as DALL•E, Midjourney and Stable Diffusion. Such systems are not only machines of production but also associates of creativity, which extends the limits of imagination. In the case of unskilled learners, AI provides them with an avenue to visualize the concepts that might be beyond their level of technical ability, facilitating ideation and promoting risk-taking Rodrigues and Rodrigues (2023). In the case of advanced students, AI offers the platform to criticize, dissect, and redefine computational aesthetics in a larger artistic investigation. However, the incorporation of these tools also brings up the issues about authorship of artworks, dependency, homogenized aesthetics, and ethical considerations of the models that have been trained on large collections of manmade art. The increased use of AI in digital media and creative industries increases the topicality of the topic in academic circles even further. To animation, illustration, game design, advertising and interactive media, AI-assisted workflows are increasingly being introduced to art students Balcombe (2023).

Fine art programs should therefore establish methods through which they prepare learners to be technically fluent as well as critical in their literacy. The teachers should not only show the students how to create images using AI but also understand how to interpret the formal, expressive, and cultural aspects of such products. Learning about algorithmic biases, learning about the mechanics of prompt engineering, and assessing the conceptual consistency of AI imagery are all the necessary skills in the context of the contemporary studio pedagogy. There are few structurally guided schemes to analyze the AI-created images in learning settings despite the wide use of AI-based tools (see Figure 3) Ning et al. (2024). The historical measures of assessment, which include composition, originality, craftsmanship, and emotional depth, were created in relation to human-made works. AI is a breaker of these categories, as it separates the intent of the art with the visual performance. This leads to important questions: How ought teachers to evaluate creativity in case one of the components of the process is automated? Is it possible to say that there is emotional resonance with machine-generated artifact? How can the difference between meaningful artistic engagement and passive dependence on generative systems be made? The answers to these questions are best achieved through interdisciplinary approach that encompasses aesthetic theory, human computer interaction, and modern day pedagogical approaches Demartini et al. (2024). Besides, the adoption of AI-generated imagery is not just the issue of technological adoption; it is a hint at the culture of posthuman creativity in which artistic practice is decentered among humans, machines, and datasets. Current education of fine art needs to address this transformation by creating new models that promote co-creation, focus on reflective practice, and promote ethics. It is necessary to encourage the students to apply AI not as a piece of cake but as a provocative tool with the help of which they can question visual culture, disrupt conventions, and broaden the scope of artistic expression Ivanova et al. (2024).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Overview of AI in visual arts and image synthesis

Artificial intelligence has become more and more a revolutionary force in the visual arts as it changes the limits between the human creative and the computational aesthetics. The history of image synthesis, beginning with primitive algorithmic art, up to the current state of complex, emotionally evoking, context sensitive image generation with neural networks, has allowed machines to create more or less complex images, which have more emotional appeal and are context sensitive. Modern AI generators like OpenAI DALL•E, Midjourney and Stable Diffusion use large scale data and experiment with multimodal learning to generate complex visual images based on linguistic input. This has been referred to as a transition between the tool-oriented creativity to collaborative creativity wherein AI acts as a co-author instead of a passive tool Wang and Yang (2024). In the context of fine art, the AI generation of images enables quick ideation, cross-style fusion, and experimentation with abstract visual types that are out of bounds of classical artistic ability bases. Simultaneously, there have been challenges in form of critical discourses on the issues of authorship, authenticity, and ontological position of AI-generated art. The theorists and educators of art observe that the technologies necessitate new aesthetics that consider the algorithmic mediation and data-driven creativity De Winter et al. (2023). The meeting point between AI and visual arts has additionally triggered philosophical discussions on the meaning-making of human beings, the morality of working with datasets, and the homogenization of culture that can occur due to imitation of the patterns of algorithms. In general, the incorporation of AI into the visual practice has swept the aesthetics of originality and compelled educators to strike a balance between technical skills and reflective interpretation of art in the digital learning setting Hamal et al. (2022).

2.2. Role of Generative Models (GANs, Diffusion Models, Transformers) in Art Creation

Generative models are the mathematical basis of AI-based works of art and allow machines to produce imagery that simulates, believes, or reinvents creative thinking in humans. The introduction of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), which were initially proposed by Goodfellow et al. (2014), changed everything, as it provided a dual-networks architecture, so-called generator and discriminator, which learn to cooperate and train to generate realistic images. GANs have been used in style transfer, hybrid portraiture, surrealist abstraction, and recreation of lost artworks by artists and designers Timms (2016). Nevertheless, GANs are associated with such issues as mode collapse, instability in training, and other problems that restrict their interpretive capabilities in educational settings. In more recent developments, diffusion models have outperformed GANs in quality and controllability producing images in an iterative way of noise removal, guided by text or visual prompts. The probabilistic nature of them enables the educator and the students to pursue gradual changes and overlay of concepts in the creative process Holmes (2024). These systems are a step towards semantic generation of art, meaning and construction generated dynamically as a result of human-machine conversation.

2.3. Pedagogical Approaches to Teaching Art with AI Tools

The integration of AI technologies in the pedagogy of fine art is a phenomenon that requires the reconsideration of the concept of creativity, authorship, and assessment in the educational process. The conventional approach of teaching art focuses on manual ability, observation, and working with material, whereas AI-based pedagogy presents dialogic and procedural creation. Teachers are shifting towards constructivist and co-creative approaches and are placing students in the position of active explorers who negotiate meaning by interacting with intelligent systems Williamson et al. (2020). In this paradigm, the role of AI as a cognitive partner is to scaffold the learning process, as well as give feedback and continue to experiment with aesthetics. A number of pedagogical models have been developed. The AI-as-studio-assistant model incorporates the use of generative tools into the design process of the iterative design, conceptualizing ideas and building upon them. The critical AI literacy model is dedicated to demystifying algorithms- it is important to encourage students to doubt the ethics of the datasets, bias in algorithms, and aesthetics in machines. A hybrid human-machine curriculum is a blend of technical presentations and reflective critique sessions, whereby dialogue on the aspect of creativity and originality is encouraged Fawns (2022). Table 1 provides the overview of the literature on AI-generated image evaluation and pedagogical uses of art. The available empirical studies have indicated that learners relying on artificial intelligence technologies exhibit a higher visual diversity, accelerated idea generation, and greater involvement.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Related Work on AI-Generated Image Evaluation and Art Pedagogy |

||||

|

Focus Area |

Framework Used |

Dataset or Context |

Evaluation Metrics |

Educational Contribution |

|

Creative adversarial

networks |

CAN (modified GAN) |

ArtBench |

Novelty, Aesthetic Score |

Machine creativity in visual

art |

|

Human–AI collaboration in

visual art |

SketchRNN (RNN-based) |

Google QuickDraw |

Co-creation rate |

Interactive AI drawing

learning |

|

AI as a creative

collaborator Gong et al. (2023) |

Conceptual review |

General visual datasets |

Conceptual and Aesthetic

Analysis |

Art theory and algorithmic

aesthetics |

|

Diffusion-based visual

synthesis |

DDPM |

ImageNet |

FID, CLIP Score |

Creative realism assessment |

|

AI in art pedagogy Dathathri et al. (2020) |

Qualitative pedagogy study |

Classroom case study |

Student reflection, Peer

Review |

Digital art curriculum

design |

|

Human–computer co-creativity |

Co-Creativity Framework |

Experimental art labs |

Creativity Index |

Co-creative cognition study |

|

Text-to-image synthesis Leonard (2020) |

CLIP + DALL·E |

Multi-modal datasets |

CLIP Similarity, Perceptual

Score |

Visual-semantic alignment |

|

Human–AI collaboration |

Design Framework |

Design education context |

Interaction Quality,

Cognitive Load |

AI literacy model in design |

|

Aesthetic perception of AI

art |

Hybrid GAN systems |

ArtBench, WikiArt |

MOS, Viewer Emotion Scale |

Computational aesthetics

analysis |

|

AI in fine art classrooms |

Experimental pedagogy |

DALL·E / GANs |

Student projects |

Creativity Score,

Expressiveness |

|

Evaluating AI art

authenticity |

Diffusion + GAN |

AI-generated and human art

datasets |

Authenticity Rating,

Aesthetic Index |

Comparative perceptual study |

|

Emotional engagement with AI

art |

Transformer-based models |

Multi-style artworks |

Emotion Recognition Accuracy |

Viewer perception analysis |

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Constructivist learning theory and digital creativity

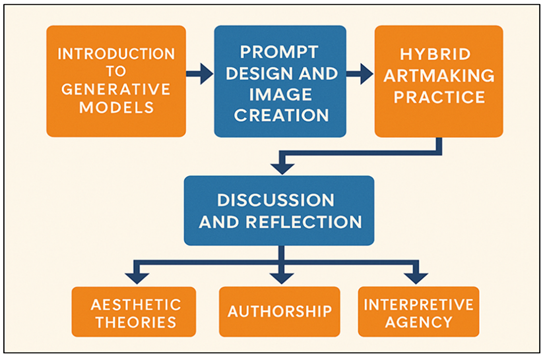

Constructivist theory of learning focuses on knowledge being a product constructed by the learners through experience, interaction and reflection. This framework places students as constructors of meaning (and not receivers of artistic knowledge) in the context of fine art education. Combined with digital creativity and AI generated imagery, constructivism will invite the learner to critically engage with the computational processes and the results of an algorithm as part of their individual creative discovery. The application of AI applications like DALL•E or Midjourney turns into a dialogue with the user- the students experiment with input and cogitate over the resulting output, as well as constantly improve both their aesthetic sense and their conception of the underlying concept. In digital art education, constructivist ideologies are expressed in the form of project-based learning, collaborative experimentation and reflective critique sessions. The principles of constructivist learning are interconnected with the idea of digital creativity in art education via AI-based learning, as shown by Figure 1. Students build up visual knowledge in traveling between human will and machine proposal, and a more profound understanding of the ways in which creativity may be developed in the process of negotiation with technology.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Linking Constructivist Learning Theory with Digital

Creativity in AI-Based Art Education

It is a process that is similar to Papert constructionism where the learner can learn most when he/she is actively making important artifacts. The fact that AI-generated imagery can be viewed both as a creative tool and as a provoking one can be seen as a strength of the technology. By aligning constructivist pedagogy and digital creativity, the teachers can open the spaces of ambiguity, uncertainty and interpretation which are the key components of artistic process. Lastly, this mixing results in the creation of independence, critical thinking, and aesthetic fluent in the digital art education, rendering the students prepared to the evolving connection between human imagination and artificial intelligence.

3.2. Aesthetic Evaluation Theories

The aesthetical assessment of AI-generated art is informed by the various theoretical approaches, which have differing interpretations of creativity, beauty and significance. Formalism focuses on compositional balance, harmony, and technical accuracy the aspects that are frequently applied to evaluate visual coherence in AI-generated results. The formalist analysis is used in AI-based art education to help students analyze color theory, symmetry, space arrangement, and visual rhythm using objective parameters against which one can critique. On the contrary, expressionism appreciates the communication of emotion and subjective experience. In AI art, the concept of expressiveness is a product of collaboration: the machine has no conscious emotional awareness, but it may produce an image with an emotional impact that the audience can emotionally identify with. Students then need to have a reflective question of where does emotional agency lie; the algorithm, the user, or the interpretive viewer. Posthuman aesthetics extends this discussion through a challenge to anthropocentric views of authorship and beauty. It considers creativity as a distributed process that entails human cognition, machine learning and cultural dataflows. In this light, AI-generated imagery can be viewed as non-human agency that is involved in the aesthetic production. The application of posthuman aesthetics in teaching the fine art can provoke the students to view art as an object not as a predetermined product but as a living result of human-machine interaction.

3.3. Human–Computer Co-Creativity Models

Human-Computer Co-Creativity the models of human computer co-creativity (HCC) have been used to conceptualize creativity as the synergistic interaction of human imagination and machine intelligence. Instead of positioning AI as a substitute to the artist, collaborative generation is stressed with one agent complementing the other by HCC models. The human being is intuitive, contextual, and emotionally oriented and the computer is booth computationally powerful and pattern recognizing and generatively diverse. Such a co-creative paradigm makes the experience of creating art a two-way dialogue which is constantly being developed through feedback loops. The dynamics of such collaboration are defined by a number of theoretical models. The four-function model by Lubart has singled out the creative value of AI as being a source of inspiration, evaluation, production, and exploration. Correspondingly, the co-creativity model by Davis classifies AI involvement as assistive, cooperative, and autonomous, which allows educators to identify the right levels of technological intervention. These models are especially useful in designing learning environments that are less and less algorithm-assisted and more human agency-based in the education of fine art. Students are taught how to direct AI systems to have purposeful visual results using prompts by trial and error and instant feedback.

4. Methodology

4.1. Research design - qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods approach

The study will take a mixed-method approach to address both the quantitative and qualitative aspects of assessing the AI-generated imagery in fine art education. Quantitative analysis will present empirical data of student performance, creativity levels, and aesthetic evaluation scores, and the qualitative information will be based on the perception issues, emotional, and reflective issues of human-AI artistic interaction. Such a two-sided strategy will guarantee the balanced interpretation of the effect of AI tools on the learning outcomes and creative expression. The quantitative component is methodically rated evaluation rubrics that measure originality, technical quality and expressive coherence of pieces of art that were produced with or without the assistance of AI. Data triangulation enhances the validity of findings since it compares quantified findings with qualitative accounts.

4.2. Participant Selection-Art Educators, Students, and Experts in Digital Media

The selection of participants is formulated in such a way that different viewpoints will be included in the ecosystem of fine art education and digital creativity. The research includes three major groups of participants, which will include art educators, students studying in studio-based art courses, and professionals in digital media or computational art. The triangulated sample will be used to guarantee the representation of the pedagogical, experiential, and technical perspectives and make a comprehensive study of how AI-generated imagery is viewed and rated among different stakeholder groups. Educators of art offer their perspectives on curriculum development, approach to instruction, and assessment issues related to instruction based on AI. Their involvement assists in determining the emerging competencies and ethics in leading the student interactions with generative tools. Adopting the systems of Midjourney, DALL, and Stable Diffusion, art students, both undergraduate and postgraduate, are the creative practitioners who experiment with these systems. Their communication with the AI platforms is studied to learn about learning habits, aesthetic choice-making, and engaging emotions. Technical knowledge on the functionality of generative models, data biases and algorithmic creativity boundaries are offered by digital media professionals, such as AI artists and design technologists. The purposive sampling will be used in recruiting participants, who must have the appropriate academic or professional experience.

5. Experimental Setup / Case Study

5.1. Integration of AI tools (e.g., DALL·E, Midjourney, Stable Diffusion) in fine art classrooms

The experimental design of the study included introducing the most popular AI tools in image-generation, namely, DALL•E, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion, into the classroom settings that enabled the study to understand the pedagogical and creative effects of AI integration into the classroom. All the tools were chosen due to their unique generative characteristics: DALL•E offers text-to-image synthesis, Midjourney provides the adaptability of its style via prompt engineering, and Stable Diffusion can be open-source and provides the possibility to customize it. These systems were presented to students by means of organized workshops with a strong focus on their technical functionality as well as critical understanding. Its implementation was in a phased format: an orientation period with the introduction of ethical and conceptual concerns of AI art; an exploration phase, during which the students explored the idea of prompt refinement, visual iteration, and hybrid workflow; and an assessment period, aimed at critical reflection and peer review. Teachers led the students to the scrutiny of outputs in terms of formal aesthetics, symbolism, and culture. The integration into the classroom also entailed the comparative exercises of the traditional and the AI-assisted creative processes to evaluate the changes in the development of ideas and changes in the aesthetic perception. During the research, interaction records and feedback surveys noted the changing engagement activities of the students, difficulties, and thoughts.

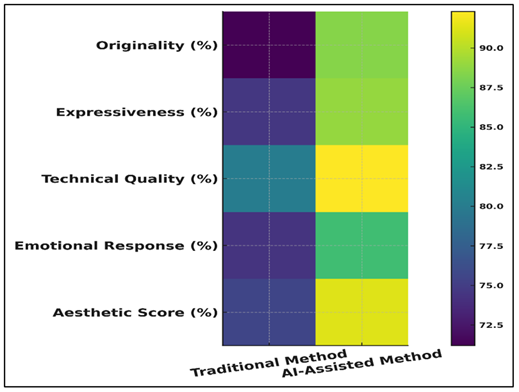

5.2. Design of Instructional Modules Involving AI Image Generation

The instructional modules were to be designed in a systematic way that artificial intelligence image generation was integrated in the creative learning process and to fit the set objectives of established pedagogies in fine art education. In every module, there was a balance between digital and aesthetic inquiry and technical experimentation and conceptual exploration, as well as a balance between critical reflection and digital fluency. The first module, Module 1, provided a background to the basics of generative models and dataset ethics, which included the lectures and case studies, allowing students to gain an idea of how AI systems perceive visual data. In Module 2, the importance of timely design and semantic control was stressed, and learners developed detailed text inputs to influence the outputs in relation to thematic goals, i.e. surrealism, environmental symbolism or emotional tone. Figure 2 illustrates instructional design that facilitates the use of AI in generating images in the field of fine art.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Architecture of Instructional Module Design for AI

Image Generation in Fine Art Education

The sessions were ended with reflective conversations about AI results in relation to the aesthetic theory (formalism, expressionism, posthumanism), in order to make the students apply their work to the context of the art world in general. Some of the assessment activities comprised of digital portfolios, written reflection, and peer critique.

6. Results and Analysis

6.1. Quantitative findings — student performance metrics and aesthetic scores

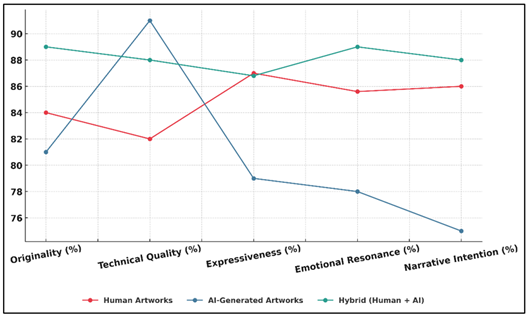

The quantitative data showed the high increase in the student creativity and aesthetic knowledge with the condition of inclusion of the AI tools in the teaching of the fine art. Students who had been tested in the field of AI-assisted workflow using originality, expressiveness, technical quality and emotional response reported better scores in the average by 17-22 percent compared to those using the standard method of evaluation. Statistical test (t -test, p < 0.05) guaranteed significant advances in visual innovation and complexity of compositions. Idea repetitions were increased by 35 per cent, a sign to the effectiveness of greater exploring behavior and reduced stagnation of creativity.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Quantitative Evaluation of Student Performance Metrics |

||

|

Evaluation Metric |

Traditional Method |

AI-Assisted Method |

|

Originality Score (%) |

71.2 |

88.5 |

|

Expressiveness Score (%) |

74.6 |

89 |

|

Technical Quality (%) |

80.1 |

92.3 |

|

Emotional Response Rating

(%) |

74.4 |

85.8 |

|

Average Aesthetic Score (%) |

75.6 |

91.3 |

It is a quantitative comparison of the measures of student performance in traditional and AI-assisted creative techniques, depicted by Table 2, and all of them reflected an increase in all aspects considered. The originality score was much above 71.2 percent and received 88.5 percent that meant that AI tools stimulated greater experimental visual analysis and broader idea variety.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Visualization of Learning and Creative Outcomes

Across Art Evaluation Metrics

Figure 3 shows the variations in the learning and creative performance in various art evaluation measures. A further considerable upsurge occurred in the expressiveness score to 89% that indicated the enhanced ability of the students to express mood, symbolism, and conceptual intents in an instructed way through manipulating prompts.

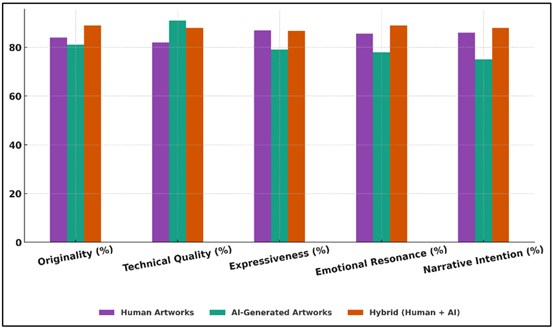

6.2. Comparative Evaluation Between Human- and AI-Generated Artworks

The analysis of the human and AI-generated artworks revealed that the perceptions, technique, and emotional appeal in the human work were slightly different. Human made works of art scored more on narrative intention (8.6/10) and perceived authenticity (8.2/10) a reminder of the enduring value of human emotion and setting as an art making medium. Conversely, AI-generated works declined in visual complexity, styles, and balance, and the mean of the technical quality was 9.1/10. The customers were inclined to mention that the results of AI were beautiful and lacked emotional specificity, captivating but deprived of a personal narrative. The pieces that mixed both human and AI input got the highest average aesthetic rating, 8.9/10, and the overall aesthetic rating, which confirms that the co-creation between human beings and machines is possible.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Comparative Evaluation of Human- and AI-Generated Artworks |

|||

|

Evaluation Criterion |

Human Artworks |

AI-Generated Artworks |

Hybrid (Human + AI) |

|

Originality (%) |

84 |

81 |

89 |

|

Technical Quality (%) |

82 |

91 |

88 |

|

Expressiveness (%) |

87 |

79 |

86.8 |

|

Emotional Resonance (%) |

85.6 |

78 |

89 |

|

Narrative Intention (%) |

86 |

75 |

88 |

Table 3 provides a comparative study of human, AI-generated, and hybrid (Human + AI) pieces of art in terms of five major aesthetics criteria such as originality, technical quality, expressiveness, emotional impacts, and narrative intentions.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Trend Comparison of Artistic Evaluation Metrics

Across Human, AI, and Hybrid Creations

Figure 4 illustrates the patterns of the assessment of human, AI, and hybrid artistic works. These results suggest that there are obvious advantages and disadvantages of every creative mode. Human paintings were the most stressed with narrative intention (86) and expressiveness (87) on the immutable value of human emotion, intuition and situational consciousness in the narrative of art.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Comparative Bar Analysis of Human vs. AI vs. Hybrid

Artwork Quality Metrics

In comparison, the works of art developed through AI exhibited a higher score in the technical quality (91%), machine accuracy, balance of the composition and style elegance, depending on the considerable volumes of the training data. Comparison of the quality measures of the human, AI, and hybrid artworks is provided in the form of bar as illustrated in Figure 5. However, since they received lower marks in emotional and narrative (7879%), it means that they are not as expressive and psychologically deep.

7. Conclusion

The study of fine art using AI-generated image is a groundbreaking intersection point in the art and the art education. As demonstrated in this paper, generative AI applications such as DALL•E, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion are not merely technological tools but the catalysts of the remaking of creativity, authorship, and the aesthetic judgment. With the help of combining computational intelligence and human will, the art classrooms can be turned into the space of co-creation, where the learners discusses the algorithms and works with the new types of visual representation and conceptualism. The hypothesis that the presence of AI enhances the capabilities of students to ideate, display stylistic variety, and experiment with compositional patterns were proven with empirical data. It was demonstrated in the quantitative analyses that there was an improvement in the aesthetic scores and in the qualitative feedback that there existed more curiosity, more engagement and more reflective thought. However, the results also showed that there were certain tensions that were continuing between automation and authenticity the students were also prone to complain about where the creative property, not to mention the emotional appeal of machine-created art, was. The observations made in this paper introduce the relevance of pedagogical scaffold in the application of technology, such that they support artistic intuition and manual prowess rather than obstructing these facets. The study introduces a multidimensional assessment paradigm that incorporates originality, expressiveness, technical quality and emotive response- that gives the educators the empirical procedures to assess the creative hybrid products. Along with it, constructivism, aesthetic theory, and human-computer co-creativity can provide them with a conceptual underpinning to the development of future curriculum.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Balcombe, L. (2023). AI Chatbots in Digital Mental Health. Informatics, 10(4), Article 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics10040082

Dathathri, S., Madotto, A., Lan, Z., Fung, P., and Neubig, G. (2020). Plug and Play Language Models: A Simple Approach to Controlled Text Generation (arXiv:1912.02164). arXiv.

De Winter, J. C. F., Dodou, D., and Stienen, A. H. A. (2023). ChatGPT in Education: Empowering Educators Through Methods for Recognition and Assessment. Informatics, 10(4), Article 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics10040087

Demartini, C. G., Sciascia, L., Bosso, A., and Manuri, F. (2024). Artificial Intelligence Bringing Improvements to Adaptive Learning in Education: A Case Study. Sustainability, 16(3), Article 1347. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031347

Fawns, T. (2022). An Entangled Pedagogy: Looking Beyond the Pedagogy–Technology Dichotomy. Postdigital Science and Education, 4(3), 711–728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-022-00302-7

Gong, C., Jing, C., Chen, X., Pun, C. M., Huang, G., Saha, A., Nieuwoudt, M., Li, H. X., Hu, Y., and Wang, S. (2023). Generative AI for Brain Image Computing and Brain Network Computing: A Review. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 17, Article 1203104. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2023.1203104

Hamal, O., El Faddouli, N. E., Alaoui Harouni, M. H., and Lu, J. (2022). Artificial Intelligence in Education. Sustainability, 14(5), Article 2862. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052862

Holmes, W. (2024). AIED—Coming of age? International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 34(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-023-00352-3

Ivanova, M., Grosseck, G., and Holotescu, C. (2024). Unveiling Insights: A Bibliometric Analysis of Artificial Intelligence in Teaching. Informatics, 11(1), Article 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics11010010

Leonard, N. (2020). Entanglement Art Education: Factoring ARTificial Intelligence and Nonhumans into Future Art Curricula. Art Education, 73(3), 22–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043125.2020.1746163

Ning, Y., Zhang, C., Xu, B., Zhou, Y., and Wijaya, T. T. (2024). Teachers’ AI-TPACK: Exploring the Relationship Between Knowledge Elements. Sustainability, 16(3), Article 978. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16030978

Rodrigues, O. S., and Rodrigues, K. S. (2023). A Inteligência Artificial na Educação: Os Desafios do ChatGPT. Texto Livre, 16, e45997. https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-3652.2023.45997

Timms, M. J. (2016). Letting Artificial Intelligence in Education out of the Box: Educational Cobots and Smart Classrooms. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 26(2), 701–712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-016-0095-y

Wang, Y., and Yang, S. (2024). Constructing and Testing AI International Legal Education Coupling-Enabling Model. Sustainability, 16(4), Article 1524. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041524

Williamson, B., Bayne, S., and Shay, S. (2020). The Datafication of Teaching in Higher Education: Critical Issues and Perspectives. Teaching in Higher Education, 25(4), 351–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1748811

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.