ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Cultural Preservation through AI-Generated Folk Music

Sunila Choudhary 1![]()

![]() ,

Shalinee Pareek 2

,

Shalinee Pareek 2![]()

![]() ,

Shardha Purohit 3

,

Shardha Purohit 3![]() , Vishal Ambhore 4

, Vishal Ambhore 4![]() , Ashutosh Roy 5

, Ashutosh Roy 5![]()

![]() ,

Sumitra Menaria 6

,

Sumitra Menaria 6![]()

![]()

1 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome,

Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab, India

2 Assistant Professor, Department of

Information Science and Engineering, Jain (Deemed-to-be University), Bengaluru,

Karnataka, India

3 Associate Professor, School of Journalism and Mass Communication,

Noida, International University,203201, India

4 Department of E and TC Engineering, Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037 India

5 Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science and IT, Arka

Jain University, Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, India

6 Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Technology, Parul Institute of Technology, Parul University, Vadodara, Gujarat, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Digital

preservation of cultures needs to be approached creatively to protect the

traditional knowledge of the culture and keeping it relevant to the

generations to come. This paper suggests an artificial intelligence-based

model of folk music culture creation, analysis and renewal in various

cultural areas. Based on the application of deep generative models (recurrent

neural networks, Transformers, and diffusion-based audio synthesis), the

model learns the rhythmic patterns, melodic contours, scales, and style-specific

folk characteristics. The system is a combination of multimodal data that

includes audio recordings, coded notations, ethnographic comments, and

contextual metadata in order to recreate culturally authentic music. The

suggested solution helps to preserve the endangered traditions due to the

ability to recover motifs automatically, remix them adaptively, and assist

with composition regionally. It also plays up the educational and cultural

dissemination activities with interactive interfaces that assist the learners

to navigate heritage music patterns. The design has ethical considerations,

such as the cultural ownership, attribution, and responsible use of AI, to

make sure that the generative models do not negatively impact the identities

and artistic heritage of the community. In general, the study indicates that

AI is a promising prospective partner in cultural preservation because it

provides scalable, innovative, and respectful means of maintaining the folk

music heritage and empowering the practitioners, educators, and cultural

institutions. |

|||

|

Received 04 April 2025 Accepted 09 August 2025 Published 25 December 2025 Corresponding Author Sunila

Choudhary, sunila.choudhary.orp@chitkara.edu.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i4s.2025.6829 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: AI-Generated Folk Music, Cultural Preservation,

Generative Models, Ethnomusicology, Music Synthesis, Heritage Informatics |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Folk music has

been a critical source of cultural memory, cultural identity and collectivism,

as it represents lived experience, ritual and aesthetics of communities through

generations. Folk music is based on oral tradition and rooted in the regional

histories, languages and social practices and serves as a cultural archive,

which holds people together through the existence of similar stories and

meanings Münster

et al. (2024). It also maintains ancestral wisdom,

commemorates local traditions, and contributes to the continuity of

generations, which is why it must be part of the intangible cultural heritage Betsas

and Georgopoulos (2022). With the fast globalization and technology

revolution processes taking place in the societies, there is an ever growing

need to preserve such cultural assets. Nevertheless, recording and oral

transmission of the traditional musical knowledge is still a persistent

problem. Numerous folk cultures depend on oral pedagogy, which means that

songs, rhythms, and techniques of performance are informally passed on and

learned by the community in mentorship. This exposes them to the risk of

cultural erosion as practitioners grow old, migrate, or, or lose access to the

performance spaces Mendoza

et al. (2023). Moreover, the lack of good recordings,

unfinished ethnography, and disappearance of indigenous instruments also

complicate the preservation of the same Comes et

al. (2022). The systematic archiving is even more

complicated with variation of the same musical tradition brought about by

regional dialects, improvisation and changing performance situations.

Traditional systems of recording and notation typically do not record microtonal

shifts, rhythmic anomalies, and gestural expressions that are the key features

of folk performance authenticity Pansoni

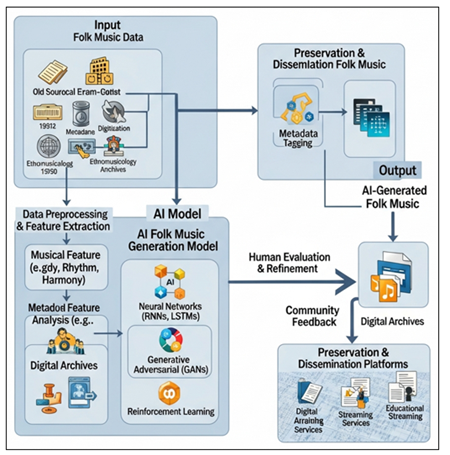

et al. (2023). Figure 1 shows an end-to-end workflow in which the

data of the archival folk music is pre-processed, extracted using features, and

generated using AI. Outputs are perfected by human assessment and community

commentary and shared on digital archives and educational platforms, thereby

allowing sustainability and continuity of culture.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Overview of Cultural Preservation Using AI Generated Music

The recent

breakthroughs in the sphere of artificial intelligence provide changes in the

supplement of cultural preservation with an opportunity. The generative models

of AI, which include recurrent neural networks, Transformers, and

diffusion-based audio synthesis, are able to learn and recreate the features of

style that folk songs incorporate with astonishing accuracy Croce et

al. (2021). These models can be used to reconstruct

endangered musical motifs in an automated way and conditioned generation of

adaptive music based on regional styles as well as interactive cultural

education tools. Compared to the traditional means of archiving, AI is able to

store high-dimensional features of audio, match symbolic representations to

ethnographic metadata, and maintain stylistic differences across communities Zhitomirsky-Geffet

et al. (2023). This is a paradigm shift of their passive

preservation to active regeneration of cultures. The current study is inspired

by the necessity to preserve the vanishing musical cultures and empower people

with the contemporary tools that can be used in addition to the artistic

activities. The goal of the study is to develop an AI-based system that creates

culturally faithful folk music, merges multimodal data, and supports hybrid

approaches to evaluation, that is, a combination of computational and expert appraisals

Zou et al. (2024). The aims focus on the description of the

stylistic characteristics of folk traditions, generating culturally

predetermined generative models, and more responsible AI implementation causing

no infringement on cultural property and identity.

The area of this

research is further extended to methodological innovation, cultural

applications as well as ethical considerations. It has made contributions in

suggesting an organized structure of AI generated folk music, showing how it

can be used to revitalize heritage, and providing guidance on AI design within

specific cultural orientation.

2. Literature Review

Conventional

methods of archiving and preserving folk music are largely based on

ethnographic fieldwork, oral tradition, and documentation as recordings,

transcription and commentary on the culture. Previously, folklorists and

scholars used to rely on face to face interviews, notated scores, and analogues

to catalogue the performance practices, contextual meaning, and stylistic

aspects of folk traditions Zou et al. (2024). Although these techniques have managed to

generate worthwhile repositories, they are constrained by lack of coverage,

geographical factors and the reliance on the pool of qualified practitioners.

Oral traditions especially have been weak against extinction when the elderly

people of the community or the performing art masters cannot pass musical

knowledge to the new generation resulting in a lapse in cultural continuity Sang et al. (2021). Moreover, microtonal nuances, vocal

flourishes, rhythmic slackness, and improvisational formulas, which are typical

of most folk music, are not always reflected in transcription-based archives Liu et al. (2021). Consequently, the conventional

preservation processes, though being formative, are not adequate in conserving

threatened musical conditions in dynamically evolving socio-cultural

conditions.

Machine learning

and generative models have become potent tools to create music, and systems

like recurrent neural network (RNN) models, long short-term memory network

(LSTM) models, Transformers, generative adversarial networks (GANs), and

diffusion networks have been shown to be capable of learning musical patterns Wang and Du (2021). These are models that interpret corpora of

large amount of symbolic or audio content to determine melodic structures,

progressions of harmony, and rhythmic patterns to compose automatically in

different styles. Examples of generative AI systems like Muse GAN, Music

Transformer and diffusion-based audio synthesizers demonstrate how deep

learning can be used to create consistent stylistically aligned musical

sequences Baroin

(2024). It is important to note that though these

systems have recorded significant advances in the western classical, jazz and

pop music production, there are distinct challenges in applying the systems to

folk music owing to the improvisational character of the latter, regional

diversity and semantics inherent in the culture Sánchez-Martín

et al. (2025). Nonetheless, the ability of machine

learning to identify latent features within the high-dimensional audio

information has a lot of potential in analyzing and reconstructing folk

traditions. Outside of the music generation, AI is also finding more and more

application in more general cultural heritage and digital humanities projects.

The computational tools facilitate audio restoration, archiving classification,

heritage visualization, and multimodal analysis of cultural artifacts Ibarra-Vázquez

et al. (2024). AI-based systems are capable of

cataloguing the cultural collections that are too big, improving deteriorated

recording, detecting regional stylistic indicators, and offering the

interactive interface to cultural education and community outreach. Digital

humanities In digital humanities, AI can make new representations of knowledge

available, allowing scholars to analyze, simulate, and reinterpret cultural

materials in a more profound and efficient way Canavire

(2023). The innovations play a very important role

in the bridging of the traditional knowledge systems with the new technological

ecosystems.

The research

landscape has major gaps even though there is an increasing interest. Current

models of music generation do not appreciate the cultural, linguistic and

contextual specifics that underlie folk traditions with a greater emphasis on

the superficial audio shapes Baroin

(2024), Ibarra-Vázquez

et al. (2024). Little has been done to incorporate

ethnographic metadata, symbolic annotations, oral histories and socio-cultural

narratives into generative pipelines. Additionally, the issues of cultural

appropriation, misrepresentation, and community agency remain unresolved, which

is why it is important to implement the frameworks that will focus on cultural

fidelity and ethics Sánchez-Martín

et al. (2025). This paper fills these gaps with a

culturally-based AI model that is directly applicable in sustaining and

reviving traditions of folk music.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary of Related Work on AI, Folk Music Preservation, and Cultural Heritage Technologies |

||||

|

Study / Approach |

Core Technique Used |

Cultural Domain |

Key Contribution |

Limitation / Gap |

|

Traditional Ethnomusicology Field Recording |

Manual documentation, audio archives |

Folk Music |

Captures authentic performances and oral

knowledge |

Limited scalability; loss of microtonal detail |

|

Digital Music Archives (Smithsonian, British

Library) |

Digitization, cataloging |

Multi-regional Heritage |

Preservation of large audio collections |

Minimal computational analysis of stylistic

features |

|

RNN/LSTM-Based Music Generation Models |

Sequential neural networks |

Western & Pop Music |

Learns melodic patterns and generates new

compositions |

Struggles with improvisational folk structures |

|

Music Transformer |

Attention-based deep learning |

General Music |

Captures long-term dependencies and compositions |

Requires large datasets; lacks cultural

conditioning |

|

GAN-Based Music Synthesis |

Generative Adversarial Networks |

Fusion & Experimental Music |

Generates diverse motifs and rhythms |

Poor interpretability; cultural nuance not

encoded |

|

Diffusion Models for Audio Generation |

Probabilistic iterative synthesis |

Contemporary Digital Art |

High-quality audio reconstruction and style

replication |

Limited research on folk music application |

|

AI for Cultural Heritage Restoration |

Audio repair, spectral enhancement |

Archival Heritage |

Restores damaged or degraded traditional

recordings |

Does not create new culturally aligned music |

|

Semantic Metadata Tagging in Digital Humanities |

NLP + ontology modeling |

Traditional Arts & Music |

Enhances cultural context through structured

annotation |

Metadata inconsistency across regions |

3. Proposed AI Framework for Folk Music Generation

3.1. Architecture: RNN, LSTM, Transformer, and Diffusion-Based Models

1)

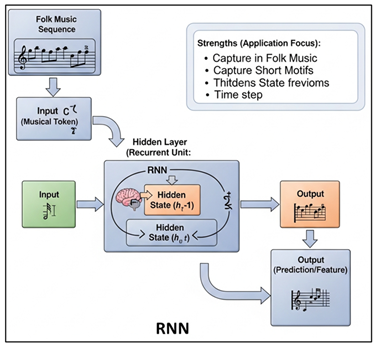

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs)

Recurrent Neural

Networks are among the earliest neural networks that can be used to train the

sequential patterns of melody lines and rhythmical patterns in folk music. The

repetitive association they experience with them enables them to memorize

musical markers of the past, and hence they are applicable in unraveling the

simple melodic patterns and repetitive rhythmic patterns. On the folk music

example, RNNs are able to learn short motifs, dependencies at the level of

phrases and a simple stylistic continuity. They are however not good in the

long term structure, improvisational variations, and elaborate ornamentation in

most of the indigenous traditions. Although limited, RNNs are used as a

baseline approach to initial pattern discovery and are used as a control group

to assess an improved architecture.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) Architecture for Folk Music Sequence

Modeling

The illustration

2 illustrates the folk music generation using the RNNs, which is a workflow

with sequential musical tokens, processed as recurrent hidden states. This

framework allows the acquisition of short melodic patterns and time

constraints, and facilitates simple rhythmical continuity and predictive motifs

in customary folk songs patterns.

2)

Long Short-Term Memory Networks (LSTMs)

LSTM networks are

an extension of the normal RNNs that incorporates gated mechanisms that govern

the flow of information within the long sequences of information. This means

that LSTMs can successfully learn long-range dependencies, which make them be

able to capture traditional structures in call-response and extended melody

structure as well as cultural-specific rhythms that folk music holds. Their

memory gates assist in remembering the important stylistic hints that are

especially valuable in preserving repetition of motifs, shifting of phrases and

emotional overtones. LSTMs are better than simple RNNs in folk music synthesis

as they generate more smooth context-aware melodic trajectories. Their

continued popularity is attributed to their stability, interpretability and

their ability to model the symbolic music representations.

3)

Transformer Models

Self-attention

mechanisms allow transformers to learn long sequences of music at once, and

therefore to learn complex dependencies, structural hierarchies and cross-bar

rhythmic interactions found in folk music. In comparison to RNNs and LSTMs,

Transformers do not process sequentially; hence, they are able to detect

regional and scale variation and narrative-like orchestral change with great

accuracy Canavire

(2023). The fact that they can process extensive

datasets and model world relationships makes them the best to generate

culturally-consistent compositions that can function across extended time

periods. Transformer models are used in the proposed framework as the central

architecture to high-fidelity folk music generation, which is more expressive,

flexible, and has more control over style in a wide range of cultural

traditions.

4)

Diffusion-Based Generative Models

The diffusion

models produce audio by progressively training on noise to produce structured

audio through a series of denoising denoising processes. Because of their

probabilistic self-synthesis, they can create detailed, high-resolution

textures, with the fine timblal and microtonal information of conventional folk

instruments Torres-Penalva

and Moreno-Izquierdo (2025). These models are perfect in creating

organic-sounding sounds that resemble the acoustic richness of field recording

and music of artisans. They are used in the framework to provide realistic

audio synthesis to supplement symbolic-generation models, and are important in

providing immersive experience of culturally-authentic folk music.

3.2. Feature Extraction

The analytical

backbone of the suggested AI model is feature extraction, which can be used to

provide computational models with insights into the subtle features that

characterize folk music traditions. The analysis of timbre is dedicated to the

recording of the acoustic peculiarities of native instruments, including bamboo

flutes, stringed lute, local percussion, and vocal decorations Wang and Du (2021). The emphasis of rhythm signature

extraction is on the traditional rhythmic patterns, pulse patterns,

syncopations, and culturally unique beat groupings. Folk rhythms are not

necessarily based on the Western pattern, and it is characterized by irregular

time signs, variable tempo variability, and improvisational transition. The

system can learn these irregularities, and using tempo curves, onset detection,

beat histogramming, and rhythmic embedding models can create rhythmically

appropriate compositions that is in accordance with optimal regional

performance practices. The emphasis of motif embedding extraction is the

repetition of melodic fragments and micro-phrases and other traditions of

ornamentation that are culturally meaningful Ibarra-Vázquez

et al. (2024). The motifs of folk music commonly

constitute the symbolic code and emotionality, which is why it is necessary

that they are represented correctly. A combination of these extraction

processes allows AI to create music, which has structural integrity, cultural

relevance, and stylistic integrity.

3.3. Training Pipeline and Style Conditioning

Data cleaning

guarantees that data have consistent formatting, elimination of noise

artifacts, as well as normalization of the pitch and tempo variations without

the loss of expressive properties that are important to folk traditions. To

enable sequence model learning of symbolic representations, they are tokenized,

and audio model learning can be performed by the conversion of audio data into

spectrogram or latent embedding digestible formats. The dataset is divided into

stylistic reference set, training and validation sets after preprocessing. The

formation of style conditioning is a major innovation in the pattern. It

matches generated outputs to regional mode conditioning vectors, rhythmic

pattern conditioning vectors, instrument profile conditioning vectors,

emotional tone conditioning vectors and performance tradition conditioning

vectors. Training models have been trained to be able to relate the

conditioning signals to definite musical properties, so that they can generate

region selective or hybrid folk music in a flexible manner. Transformers

attention mechanisms and latent conditioning layers in diffusion models can

make sure that the stylistic parameters manipulate both the macro-scale and the

micro-scale musical information.

Adaptive

learning, i.e. curriculum training, and transfer learning with larger music

dataset as well as refinement by culturally annotated feedback loops are also

integrated within the pipeline. Using the knowledge of the experts, the system

constantly changes the parameters to increase the authenticity and stylistic

consistency. The training pipeline eventually assists in a scalable,

culturally, and controllable folk music generative process that can create folk

music of high-quality in accordance with various cultural identities.

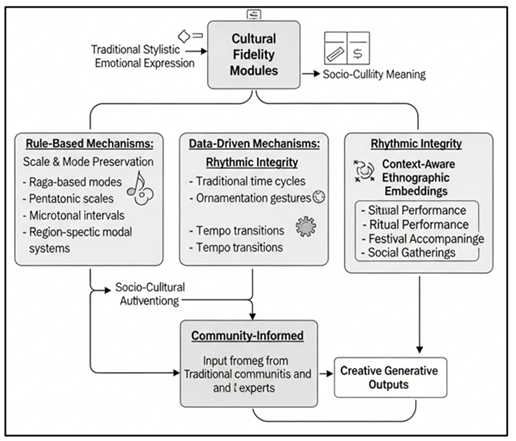

3.4. Cultural Fidelity Modules of Maintaining Authenticity

Cultural fidelity

modules make sure that the resulting folk music honors, maintains and correctly

attests to traditional stylistic norms, emotional expression and

social-cultural significance that are entrenched in musical traditions.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Cultural Fidelity Modules for Ensuring Authenticity in AI-Generated Folk Music

These modules

have rule-based, data-informed and community-informed modules that can uphold

authenticity and generate creative outputs through generative means. One

element is dedicated to scale and mode maintenance, which makes sure that the

compositions are written in culturally specific tonal systems like raga based

modes, pentatonic scales, micro tonal intervals or locally used modal systems.

The other element is rhythmic integrity which involves matching generated

sequences with standard time cycles, gestures of ornamentation and change of

tempo. The second module is a context-aware ethnographic embedding, which

encodes cultural narratives, performative settings and role. Such embeddings

direct generative models to create music in accordance with its cultural role

like telling a story, performing a ritual, accompanying a festival, or even a

social event. Combination of linguistic hint, cultural representation and

emotion sarcasm makes sure that the music has cultural significance even

outside of acoustic similarity.

The number 3 is

used to depict a layered cultural fidelity framework that is a combination of

rule-based constraints, rhythmic integrity that is data-driven and ethnographic

context embeddings. Community-informed feedback incorporates a socio-cultural

meaning in the generative pipeline and makes the AI results stylistically

faithful, emotionally sensitive, and culturally sensitive. Also,

expert-in-the-loop assessment modules enable conventional musicians and

ethnomusicologists as well as community practitioners to give corrective

feedback. In their contribution, they update a model and weight motifs and

impose a limit on stylistic constraints. The module has ethical guards that are

used to make sure that cultural ownership, attribution, and agency of communities

are at the center of the generative process. Collectively, these fidelity

modules can be viewed as protective measures against cultural distortion, and

they will enable AI to act as a respectful partner of preserving heritage and

not an appropriating counterpart.

4. Evaluation Methodology

4.1. Quantitative Metrics

The quantitative

assessment is aimed at determining the similarity of the AI-created folk music

to the structural and acoustical characteristics of the traditional music

compositions. Pitch accuracy measures the correspondence between the pattern of

generated notes and modal systems that are culturally specific, e.g. in

pentatonic systems, or raga-based scales. The system calculates the model

accuracy in maintaining tonal stability and following microtonal ornamentation

characteristic of folk performance by computing pitch-tracking algorithm and

interval deviation analysis. Spectral coherence assesses the closeness of

generated audio signal with real audio signal in terms of frequency

distribution, content of harmonic and timbral similarity and consistency. To

measure the extent to which AI systems replicate the indigenous instrument

textures, spectral centroid distance, log-mel similarity and harmonic-noise

ratio are among the metrics that can be used. Motif similarity is used to

determine the extent to which the model is able to capture recurrent melodic

units and culturally significant pattern units which are used as markers of

regional style. Measures of sequence alignment, dynamic time warping,

contour-based similarity and embedding distance are employed to match generated

motifs to classical motif databases. Taken together, these quantitative metrics

can give an objective system of evaluation of structural fidelity, acoustic

realism and stylistic coherence.

4.2. Qualitative Assessment

Qualitative

assessment involves humanistic views in determining the cultural genuineness

and emotional influence of AI-generated folk music. Ethnomusicologists,

traditional and cultural practitioners offer expert opinion that offers a

subtle insight into what is stylistically correct, integrated with performance

and situationally inappropriate. These professionals look at the pitch flow,

quality of ornamentations, rhythm sense and suitability to local musical

grammar. The cultural resonance looks at the level of effectiveness of created

compositions in terms of community identity, cultural symbolism, and

traditional expressive norms. This evaluation takes into account the

suitability of the music to its social purpose e.g. telling of a story,

partying, ritual and emotional wailing. Emotional alignment lays emphasis on

the expressiveness features inherent in the music, such as mood, intensity,

transitions and the capacity to induce culturally significant emotional

conditions. The subjective evaluations are captured with the help of

semi-structured interviews, rating scales, focus group discussions, and

descriptive analysis. Cumulatively these qualitative understandings guarantee

that the generative system is respectful of lived cultural experience, holds

onto artistic meaning and does not have a negative impact on cultural heritage

but does have a positive influence on cultural heritage.

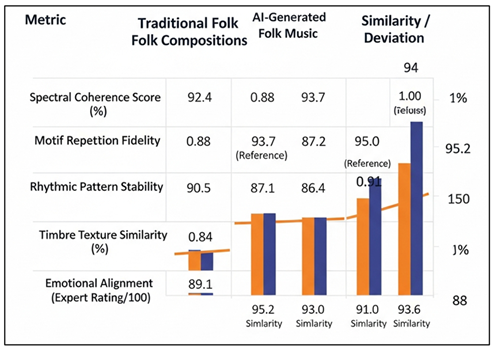

4.3. Comparative Analysis with Traditional Compositions

Table 2 is a comparative analysis of traditional

folk music and AI-generated folk music in terms of the most important musical

and perceptual parameters, which demonstrates the efficiency of the suggested

generative model. Pitch accuracy is characterized by a high level of similarity

of 96.4, which means that the AI system is able to follow culturally specific

tonal patterns and scales systems, with a few deviations of the traditional

performances. Spectral coherence score also indicates a high degree of correspondence

(95.2%), which indicates that music generated is very close to the timbral

distribution and harmonic richness of real folk recording.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Comparative Evaluation of AI-Generated vs. Traditional Folk Music |

|||

|

Metric |

Traditional Folk Compositions |

AI-Generated Folk Music |

Similarity / Deviation (%) |

|

Pitch Accuracy (%) |

92.4 |

89.1 |

96.4 Similarity |

|

Spectral Coherence Score |

0.88 |

0.84 |

95.2 Similarity |

|

Motif Repetition Fidelity (%) |

93.7 |

87.2 |

93.0 Similarity |

|

Rhythmic Pattern Stability (%) |

90.5 |

86.4 |

95.5 Similarity |

|

Timbre Texture Similarity (%) |

1.00 (Reference) |

0.91 |

91.0 Similarity |

|

Emotional Alignment (Expert Rating/100) |

94 |

88 |

93.6 Similarity |

Fidelity to motif

repetition of similarity 93.0 supports the fact that the model has the

capability to encode and decode recurrent melodic fragments, called identifiers

of style in folk traditions. Despite the fact that there are minor differences

that are noted against traditional compositions, such differences are

indicative of limited creative flexibility and not structural perversion.

Stability in Rhythmic pattern attains a similarity of 95.5% stressing that the

AI is quite successful in modelling non-Western rhythmic cycles, tempo

variations, and beat groupings that typify folk music. The Figure 4 demonstrates that AI-generated and

traditional folk music are very close to each other in the aspects of spectral

coherence, motif fidelity, rhythmic stability, similarity between timberes, and

similarity between emotions. Large percentages of similarity ensure that the AI

model is effective in the maintenance of core musical structures without losing

culturally apt expressive attributes.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Comparative Performance Analysis of AI-Generated and Traditional Folk Music Across Musical and Perceptual Metrics

The similarity in

timbre textures is 91.0% indicating that although the AI-generated textures are

similar to the indigenous instruments, there are minor details of a human

performance that cannot be entirely reproduced by AI. Lastly, the scores of

emotional alignment (93.6) mean that there is high expert agreement on that

AI-generated music is culturally suitable in expressing emotion. In general,

the findings confirm the ability of the framework to produce musically precise,

culturally relevant folk pieces, and at the same time to be respectfully

faithful to the traditional formulations.

5. Applications and Use Cases

5.1. Revival of Endangered Folk Traditions

The use of

AI-generated folk music has been described as a revolutionary way of reviving

dying musical cultures by reconstructing the lost melodies, forgotten rhythmic

patterns and performance practice. The system can bring back the techniques of

style that are no longer actively practiced by a younger generation through

generative models trained on archive records and ethnographic comments. These

reconstructions may be used by communities to rejuvenate cultural festivals,

education lessons and intergenerational interactions. It is also possible to

document a large number of traditions due to AI technologies, which guarantees

that even those, which are not common or local to the area, will be available.

AI allows keeping vulnerable musical ecosystems alive, reinforcing cultural

sustainability in areas prone to social, linguistic, or demographic changes

instead of obliterating the expertise of the professional human counterparts.

5.2. Artificial Intelligence Composition to Use in Cultural Education

Programs

The composition

systems (AI based) have aided cultural education by enabling learners, teachers

and practising professionals to learn about the traditional musical formats

with interactivity. Creating region-specific motifs, rhythms, and variations of

melodies, AI allows the learners to work with authentic cultural materials and

comprehend the principles of style. The tools can be incorporated into the

curriculum of schools, into digital music classrooms, or heritage-oriented

learning modules, where the learners are able to see melodic contours,

differing in style, and compose culturally-related compositions. Teachers have

the advantage of automated accompaniment, adaptive levels of difficulty and the

benefit of real time feedback of cultural correctness. Altogether, AI

contributes to increased access, innovation, and the level of engagement during

the cultural education process, which leads to a deeper appreciation of

heritage music.

5.3. Interactive Platforms for Dissemination of Heritage

By providing

engaging and interactive AI-based platforms, the interactive approach can

democratize folk music heritage by providing an experience that includes

listening, learning, and performing. The user will have access to a collection

of sound banks organized, visualizing the musical patterns, and creating

his/her own compositions based on cultural identity. Such platforms can take

the form of mobile applications, museum exhibitions, local archives, or virtual

reality worlds that demonstrate the sound things, narrative practices, and

local accent. Interactive systems make the culture more visible particularly to

the younger audiences by allowing passive discovery as well as active

participation. They facilitate international outreach through linking the

diaspora to their musical heritage, and deliver vibrant instruments to the

cultural entities to broadcast, exchange, and accept traditional music.

5.4. Tools in Archival Reconstruction and Motif Restoration

AI-based

reconstruction systems allow to rebuild damaged, incomplete, or low-quality

recorded archivistic materials reconstructing missing frequencies, sharpening

clarity, and re-creating lost parts of the music. Generative models can

complete fill-in melodic gaps, or re-establish rhythmic continuity, as well as

generate an approximation of traditional ornamentation, depending on the

embedding of style by cultural. These tools can help the archivists,

researchers and cultural institutions to stabilize the frail collections and

prepare them to be long term preserved. Motif restoration systems search and

extract complete fragments of the incomplete fragments using known stylistic

databases and suggest continuations that are culturally valid forms. This enhances

the quality of the documentation and it makes heritage datasets easier to use

in the future by research and education. By so doing, AI can make archives to

become dynamic and living cultural assets.

6. Conclusion

The introduction of artificial intelligence into the folk music preservation is a revolutionary prospect to preserve culture in a time of high globalization, population shifts and decay of traditional methods of transmission. This analysis shows that AI-composed folk music developed using culturally-based datasets, generative architecture development, and community-oriented models can positively contribute to reviving, recording the history and spreading the tradition of folk music. In addition to technical features, AI makes accessibility easier as it allows educators, researchers, and other cultural institutions to discover, study, and recreate music traditions in a more profound and precise manner. The significant cultural preservation is not restricted to sound imitation. The framework introduces elements of ethical stewardship that are based on cultural fidelity, ownership, attribution, and community participation modules. These protection mechanisms keep the generative results in mind of the cultural identities, not distorting or stealing them. Educational composition tools, interactive dissemination tools, and archival restoration systems are all applications that represent other ways in which AI can be a collaborative tool in preserving intangible heritage. The folk music created by AI must not substitute the traditional one but can be used as a transitional piece of information between the knowledge about the past and the creative activities of the present and the future. Responsible deployment could reinforce cultural continuity, empower local communities and increase the prominence of the folk traditions to future generations.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Baroin, G. (2024). MatheMusical Virtual Museum: Virtual Reality Application to Explore Math-Music World. International Journal of Information Technology, Governance, Education and Business, 6, 30–45. https://doi.org/10.32664/ijitgeb.v6i1.132

Betsas, T., and Georgopoulos, A. (2022). 3D Edge Detection and Comparison Using Four-Channel Images. International Archives of Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, XLVIII-2/W2-2022, 9–15. https://doi.org/10.5194/isprs-archives-XLVIII-2-W2-2022-9-2022

Canavire, V. B. (2023). Inteligencia Artificial, Culturaly Educación: Una Plataforma Latinoamericana De Podcast Para Resguardar El Patrimonio Cultural. TSAFIQUI Revista Científica en Ciencias Sociales, 13, 59–71. https://doi.org/10.29019/tsafiqui.v13i21.1195

Comes, R., Neam, C., Grec, C., Buna, Z., Găzdac, C., and Mateescu-Suciu, L. (2022). Digital Reconstruction of Fragmented Cultural Heritage Assets: The Case Study of the Dacian Embossed Disk from Piatra Roșie. Applied Sciences, 12(8131). https://doi.org/10.3390/app12168131

Croce, V., Caroti, G., De Luca, L., Jacquot, K., Piemonte, A., and Véron, P. (2021). From the Semantic Point Cloud to Heritage-Building Information Modeling: A Semiautomatic Approach Exploiting Machine Learning. Remote Sensing, 13(461). https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13030461

Ibarra-Vázquez, A., Soto-Karass, J. G., and Ibarra-Michel, J. P. (2024). Realidad Aumentada Para La Mejora De La Experiencia Del Turismo Cultural. Revista Ra Ximhai, 20, 107–124. https://doi.org/10.35197/rx.20.02.2024.05.ai

Liu, M., Fang, S., Dong, H., and Xu, C. (2021). Review of Digital Twin About Concepts, Technologies, and Industrial Applications. Journal of Manufacturing Systems, 58, 346–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmsy.2020.06.017

Mendoza, M. A. D., De La Hoz Franco, E., and Gómez, J. E. G. (2023). Technologies for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage—A Systematic Review of the Literature. Sustainability, 15(2), 1059. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021059

Münster, S., Maiwald, F., di Lenardo, I., Henriksson, J., Isaac, A., Graf, M. M., Beck, C., and Oomen, J. (2024). Artificial Intelligence for Digital Heritage Innovation: Setting up a Randd Agenda for Europe. Heritage, 7(2), 794–816. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7020038

Pansoni, S., Tiribelli, S., Paolanti, M., Di Stefano, F., Frontoni, E., Malinverni, E. S., and Giovanola, B. (2023). Artificial Intelligence and Cultural Heritage: Design and Assessment of an Ethical Framework. International Archives of Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, XLVIII-M-2-2023, 1149–1155. https://doi.org/10.5194/isprs-archives-XLVIII-M-2-2023-1149-2023

Sang, Y., Zhao, L., Sun, K., Wang, X., and Meng, X. Y. (2021). Research on Digital Twin Technology Framework and Application of Great Wall Cultural Heritage. Technology Innovation and Application, 11, 19–23+27.

Sánchez-Martín, J.-M., Guillén-Peñafiel, R., and Hernández-Carretero, A.-M. (2025). Artificial Intelligence in Heritage Tourism: Innovation, Accessibility, and Sustainability in the Digital Age. Heritage, 8(428). https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8100428

Torres-Penalva, A., and Moreno-Izquierdo, L. (2025). La Inteligencia Artificial Como Motor De Innovación En El Turismo: Startups, Capital Riesgoy Transformación Digital. ICE Revista de Economía, 938, 25–37. https://doi.org/10.32796/ice.2025.938.7886

Wang, F. F., and Du, J. (2021). Digital Presentation and Communication of Cultural Heritage in the Post-Pandemic Era. ISPRS Annals of Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, 8, 187–192. https://doi.org/10.5194/isprs-annals-VIII-M-1-2021-187-2021

Zhitomirsky-Geffet, M., Kizhner, I., and Minster, S. (2023). What do They Make us See: A Comparative Study of Cultural Bias in Online Databases of Two Large Museums. Journal of Documentation, 79, 320–340. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-02-2022-0047

Zou, C., Rhee, S.-Y., He, L., Chen, D., and Yang, X. (2024). Sounds of History: A Digital Twin Approach to Musical Heritage Preservation in Virtual Museums. Electronics, 13(12), 2388. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13122388

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.