ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Intelligent Curation of Digital Portfolios for Artists

Shilpi Sarna 1![]() , Vimal Bibhu 2

, Vimal Bibhu 2![]() , Debayan Das 3

, Debayan Das 3![]()

![]() ,

Yaduvir Singh 4

,

Yaduvir Singh 4![]()

![]() ,

Guntaj J. 5

,

Guntaj J. 5![]()

![]() ,

Swetha Rajagopal 6

,

Swetha Rajagopal 6![]()

![]() ,

Anupama Abhijeet Deshpande 7

,

Anupama Abhijeet Deshpande 7![]()

1 Lloyd Law College, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201306, India

2 Professor, School of Engineering and

Technology, Noida, International University, 203201, India

3 Assistant Professor, Department of Animation, Parul Institute of Design, Parul University, Vadodara, Gujarat, India

4 Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering (AI), Noida Institute of Engineering and Technology, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

5 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab, India

6 Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Presidency University, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

7 Department of Engineering, Science and Humanities, Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Intelligent

curation represents a novel paradigm of digital art management where AI

exists to supplement human creativity to make artistic portfolios more

organized, interpreted, and personal. The current work describes a multimodal

system consisting of computer vision, transformer-based language models, and

reinforcement training that allows creating adaptive, explainable, and human

aligning curation. The system evaluates works of art in terms of visual,

semantic and emotional embedding to come up with aesthetic scores and

curatorial suggestions which develop through the feedback of artists,

curators and viewers. As proven by experimental case studies, such as solo

views, multi-artist shows, and bespoke experiences of the viewer, AI can be

used to improve the coherence of the curatorship, the range of subjects, and

the experience of the viewer without losing interpretive integrity. The

system has been assessed by precision, F1-score, aesthetic diverse metrics,

and engagement index to indicate that the system is analytically robust. The

conclusion of the paper is that human-AI co-curation is a contributor to a

collaborative form of intelligence that builds upon the data analytics of

curatorial reasoning into culture making and provides an ethically sound and

scalable channel through which digital exhibition design can be carried out

in the future. |

|||

|

Received 03 April 2025 Accepted 08 August 2025 Published 25 December 2025 Corresponding Author Shilpi

Sarna, shilpi.sarna@lloydcollege.in

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i4s.2025.6825 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Intelligent Curation, Digital Portfolios, Aesthetic

Scoring, Art Recommendation Systems, Explainable AI, Cultural Informatics,

Digital Exhibition Design |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Genesis of Intelligent Curation

Intelligent curation is a phenomenon that arises in the convergence of art, AI, and digital culture- but the algorithms are not just organizational instruments, but actively involved in the aesthetics interpretation. With the growth of artists moving to digital platforms, the challenge of the intelligent systems able to interpret, analyze, and deliver the artistic works in a meaningful way has grown. Human intuition and cultural literacy such as traditional curation are now challenged by online art repositories with their enormous size and the wide range of art products Aslan et al. (2022). The process demands a change of mind - in other words, the passive displays of portfolios get replaced by active environments, ones that can change depending on the situation and the behavior of the audience according to the artistic progression. The digital age makes documentation of an artist portfolio not restricted to the parameters of documentation; it is a living ecosystem of creative data. In every single piece of art, there are visual, semantic and emotional indications, which are coded in pixels, textures and metadata. Smart curation seeks to unravel these pointers, map aesthetic relationships, dynamic trends in style and subject continuation that are likely to be missed in manual curating McIntosh and Morse (2015). With a combination of computer vision, natural language processing and deep learning machines process visual information; it also processes artistic expressions; and synthesizes information in a consistent storytelling. This synthesis is making the digital portfolio a dynamic interface such as an intelligent object that learns through interactive patterns and is conscious of the desire to make something and grow along with the artist Medjani et al. (2019).

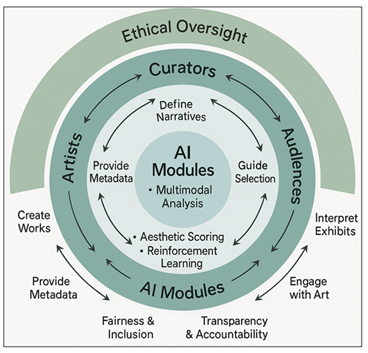

Figure 1

Figure 1 Cognitive–Computational Synergy in Intelligent Curation*

Intelligent curation has its origins in the wider field of computational creativity, in which algorithms take the place of curators, critics, and other agents of cultural mediation. Artificial intelligence is more than a process of data classification in this paradigm, artificial intelligence is the development of the ability to interpret meaning. As an example, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and vision transformers (ViTs) can learn the style features, including brushstroke density or compositional symmetry, whereas multimodal models such as CLIP can connect visual and linguistic features to image and abstract concepts or moods as demonstrated in Figure 1. Reinforcement learning opens flexibility, and AI can optimize their curatorial decisions with feedback of artists, viewers, or professional critics, eventually adapting algorithmic selection to human aestheticism. The reason behind this development is practical and ideological. On the one hand, the digital art increases exponentially and requires scalable and intelligent systems to control, suggest, and contextualise creative work. Conversely, smart curation challenges the traditional concepts of authorship, taste and the creator-audience dynamic Moulard et al. (2014). Combining the human sensitivity and computational reasoning, it forms hybrid intelligence, in which algorithms are co-workers, rather than substitutes in the process of artistic interpretation. This synergy enhances the visibility of art, makes it democratic by allowing access to global audiences, and creates personal experiences by providing art, adaptive recommendation engines and generative presenting models.

2. Cognitive and Computational Foundations

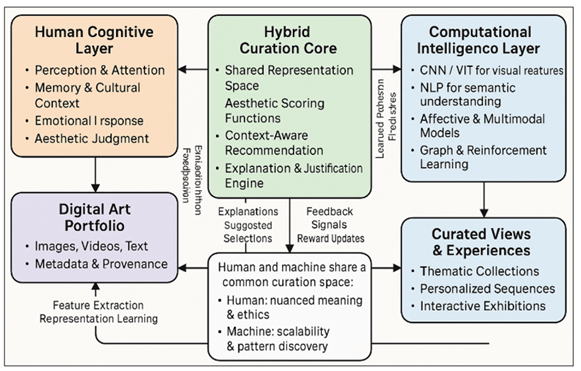

Intelligent curation is based on the integration of cognitive psychology, computational intelligence and aesthetic theory. In a nutshell, it attempts to mimic- but not to replace- the human thought process of watching, understanding and appreciating artistic expression. Human curation is multisensory and interpretative; it includes identification of symbolic meanings, cultural context, emotional undertones of the work and the intent of the artist. It is an intense interaction between art cognition and computational modeling, in which perception can be operationalized and interpretation programmable, that such phenomena of abstract cognitive systems can be translated to machine-understandable representations Dawson (2020). The cognitive perspective suggests that the process of aesthetic appreciation is a combination of perception, memory, emotion and judgment. According to neuroscientific research, the aesthetic reactions engage various brain activities that relate to reward, empathy and conceptual abstraction. These lessons drive computational analogies- neural networks which simulate the sequential processing of visual, semantic and affective information as depicted in Figure 2. As an example, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are modelled after the human visual cortex, which breaks down artworks into a sequence of color, texture and form patterns Dolan et al. (2019). In the meantime, the attention based architectures such as Transformers mimic selective attention, so that models not only learn to give weight to features in the context, such as symbolism or artistic genre, much like human observers prioritize focal points in a painting or sculpture. The fusion of emotion and meaning is also a part of cognition of art, which historically was not easy to achieve with the help of machines. The new field of affective computing has helped fill this disconnect by simulating emotional valence and arousal by using multimodal signals like color palettes, symmetry of composition, and tone in statements by artists. To guess the mood or the intensity of expressiveness of artworks, emotional AI systems are now utilizing sentiment analysis, facial-emotion mapping, and deep generative encoders. This, combined with cognitive thought, allows AI to not only see what an artwork is, but also feel how to create a sense of the human curator to the aesthetic resonance González et al. (2024).

Figure 2

Figure 2 Cognitive–Computational Synergy in Intelligent Curation

Intelligent curation frameworks represent artistic data as ontologies and graphs on the computational side using knowledge representation models. These ontologies are digital and establish notions of relationship between artists, styles, periods, techniques and cultural movements in a semantic framework on which contextual awareness is built. These systems have the ability to walk through connected aesthetic space, making latent associations, such as the thematic similarities between surrealist and digital art or cross-cultural stylistic similarities Bose et al. (2021). Moreover, multimodal learning is the epistemic gap between visual and linguistic interpretation. Such models as CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training) train simultaneous embeddings in such a way that visual features are in line with the textual semantics that the AI systems can extract the artistic meaning, titles, and conceptual descriptions of the artwork. The multimodal synergy widens the reasoning of the curator: the system is capable of not only promising artworks similar in appearance but also similar in conception or mood Serota (2023). Therefore, the combination of the cognitive and computational bases develops a dual intelligence concept, the concept that combines the human aesthetic reasoning and the machine learning abstraction. Cognitive layer tells empathy, cultural awareness, and interpretive subtlety and the computational layer brings scalability, pattern recognition as well as learns adaptively. Their intersection produces a hybrid structure which can influence audience emotion and respond to it, as well as maintain the authenticity of the curator Mughal et al. (2022). It is in this synergy that the meaning of intelligent curation can be realized, a feeling-computation balance, so that digital creativity can be very human despite being subject to machine logic.

3. Curation Intelligence Framework

The curation intelligence model offers the conceptual basis of the transformation of digital portfolios of works existing as static collections to dynamic, meaning-conscious ecosystems. As opposed to considering artworks as independent files or thumbnails, the frameworks represent every work as multi-dimensional rich object situated in the space of aesthetics, semantics, and context. The essence of this concept is that a simple metadata-based organization (by title, date or tag) is replaced by a more intelligent, ontology-based curation, where links between works, artists, styles and stories are explicitly described and computationally utilized. This allows the system to not just access appropriate artworks, but to compile them into logical chains, thematic groups and custom viewing experiences that both reflect the intention and taste of the artist as well as the audience. One of the main features of the framework is the multi-dimensional ontology of art assets, which establishes the connection between artworks, artists, techniques, genres and cultural movements as well as conceptual themes Goodfellow et al. (2016). The artworks are coded by various means: visual features (color scheme, composition patterns, texture), semantic features (topic, symbolism, story), emotional features (mood, emotive coloring), and provenience (date of creation, medium, displays, etc.). Some of the queries that can be reasoned with help of this ontology are e.g. show introspective portrait works with muted palettes made in the year of experimentation of the artist or curate a series that tracks the development of geometric abstraction over the career of the artist. Such relations embedded by the framework allow it to go beyond the matches of keywords and enable contextual interpretation and mapping of meaning. Over this ontological layer, the framework proposes an intelligent curation loop that is a combination of perception, reasoning and adaptation. During the perception part, AI models like CNNs, vision transformers, and multimodal encoders are used to extract visual and textual embeddings in the content of portfolios.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Algorithmic Model Components and Mathematical Representation |

|||

|

Model / Module |

Technique Used |

Learning Objective |

Evaluation Metric |

|

Visual Encoder |

CNN / ViT |

Extract visual

composition and style features |

Feature coherence,

PSNR, SSIM |

|

Text Encoder Lee

and Cha (2016) |

BERT / CLIP |

Embed semantic &

conceptual context |

Cosine similarity,

alignment loss |

|

Multimodal Alignment |

Contrastive Learning |

Align visual–text

pairs |

Alignment accuracy,

F1-score |

|

Aesthetic Scoring Imran

et al. (2023) |

Regression / Weighted

Model |

Compute

visual–conceptual quality |

RMSE, correlation with

expert rating |

|

RL Optimization Tashu

et al. (2021) |

Policy Gradient /

Q-learning |

Maximize

engagement-based reward |

Reward gain,

convergence rate |

This common space is utilized by the reasoning stage to create candidate curatorial sets with the assistance of graph-based structures and constraints based on rules. The sets can be themed, styled, chronologically, or audience-focused, and can be goal-oriented, like in the case of diversity, coherence, or novelty. The aesthetic scoring functions are able to assign several dimensions or technical quality, stylistic consistency, originality and emotional impact to composite indices. Nevertheless, these scores are not received as absolute ratings; they are adjusted by curatorial choices, artist-assigned limitations and audience feedback statistics (e.g., the time spent watching, pattern of interactions, likes or comments). This creates a human-AI co-curation paradigm, in which curators have the opportunity to promote, downrank, or annotate system suggestions, and the system is informed of the interference to improve future suggestions. Lastly, the framework has a feedback-based adaptation mechanism, which is also driven by reinforcement learning or bandit algorithms, and which continuously makes curation strategies better with time. Whenever a curated selection is launched, whether as a digital exhibition, as a portfolio view, or as a personalized suggestion, the system observes engagement cues and determines whether its goals (e.g. engagement diversity or narrative clarity) have been achieved. Responses made in a positive manner boost the policies on which they are built and low-level engagement leads to alternative sequencing, clustering, or thematic focus. This makes the curation process not a decision-based on design but rather a continuous dialogue between the artist, the curator, the audience, and the machine.

4. System Blueprint and Technical Architecture

The smart portfolio curation platform is organized into a multistage ecosystem that incorporates the user interaction interfaces, AI-powered analytic engines, knowledge bases, and feedback-based governance. This system blueprint, as visualised in Figure 3, transforms the conceptual curation intelligence structure a scalable technical architecture that is free to interpret, make aesthetic judgements, and generate adaptive exhibitions. The layers play a different functional role, which is overall such that the system is able to understand, reason and evolve with the continued collaboration between curator and the machine. The Client and Interface Layer contains three different user touchpoints on the platform, which are the Artist Portal, Curator Console, and Audience Experience Interface. Artists post their creative works, add metadata, and define preferences related to curation on the site, like the theme or exhibition purpose. The curator makes a review, modifies, or gives the thumbs up to collections suggested by AI on a console and adds semantic or emotional tags or labels to artworks. Meanwhile, viewers consume content that has been curated by getting personalized feeds and thematic feeds, as well as feedback mechanisms that capture what they liked, how much time they spent on it, and how much they felt about it. All the communication goes through an API Gateway which handles authentication, access control and data flow between users and the services in the back-end using REST or GraphQL endpoints. The system has a brain, which is the Curation Intelligence Layer. It is driven by a Curation Orchestrator, which arranges incoming tasks, be it portfolio organization, exhibition assembly or refining recommendations as in Figure 3. It appeals to specialized sub modules: the Aesthetic Scoring Engine rank by Compositional balance, stylistic coherence, and emotional tonality over art images: using learned embeddings; the Recommendation Engine builds portfolios of candidates optimized by diversity and thematic price; and the Explanation and Justification Module produces explanations on why the AI has made that choice: highlighting features or patterns that were the basis of AI choice. This explainability aspect will provide transparency among curators and strengthen human supervision. A Feedback and Reinforcement Learning (RL) Manager provides a Feedback Control loop by examining the curator manipulation and audience interactions metrics to revive policy parameters, and adjust the system curatorial logic processively to the changing aesthetic norms.

Under this is Analysis and Representation Layer in which

the raw artistic data is converted to computationally rich representations.

Formal attributes (color harmonics, brushstroke

patterns, and spatial composition) are formal attributes decoded by the

Computer Vision Feature Extractor (a CNNs or Vision Transformer based).

Simultaneously, NLP and Multimodal Encoder (with the help of model like BERT or

CLIP) processes textual documents - Artist statements, title and explanations

of the theme - so that linguistic and visual semantics coincide in a common

latent space. The Affective and Emotion Analyzer decoys the expressive

dimensions such as the mood or intensity based on multimodal sentiment fusion.

The products of these modules are stored at an Embedding and Feature Store,

which forms the basis of the unified aesthetic representation of the similarity

search, clustering, and retrieval activities. This shop is important in making

sure that the system is capable of executing

sophisticated aesthetic reasoning in various modalities of art.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Deployment Diagram of Intelligent Portfolio Curation Platform

Knowledge and Data Layer provide the system with ordered and enduring depositories. Media Repository: files with original artwork and their preview are stored there, and profiles of artists, their exhibition history, and technical descriptions are stored in the Metadata and Portfolio Database. The Ontology and Knowledge Graph is placed up above, coded relationships between artists, artistic movements, techniques, and symbolic themes. This graph allows making a contextual inference, i.e. being able to assert the presence of stylistic influences, or the chronological development of concepts through works. Behavioral data (views, clicks, comments, or dwell times) is logged during the Engagement and Analytics Store to provide input to the RL manager and aesthetic scoring functions, so that the resulting results of curation are sensitive to the real-life audience dynamics. Lastly, Infrastructure, Monitoring, and Governance Layer guarantees a sound operation, scalability and ethical integrity. The Model Registry has addressed trained versions of AI models, logs the performance metrics, and A/B experiments. The Monitoring and Logging module is a continuous system health evaluation, model drift detection and critical events are logged to be audited. A special component of Security and Access Control is used to implement role-based access control, encrypt data in transit and storage, and define compliance with privacy and copyright regulations frameworks- crucial in the administration of intellectual property and artist loyalty.

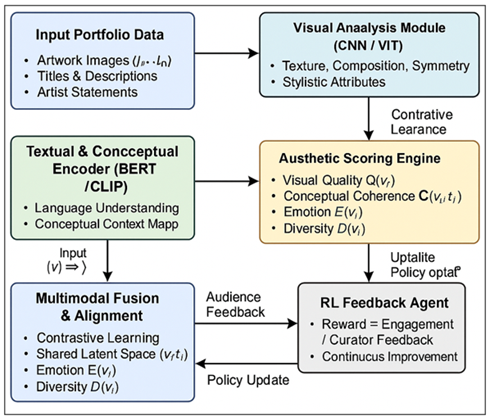

5. Algorithmic Design and Learning Models

The intelligent portfolio curation platform is based on the algorithmic core that combines various paradigms of learning, computer vision, natural language processing, multimodal representation learning, and reinforcement learning, to help to attain perceptual learning, contextual reasoning, and adaptive recommendation. It is a hybrid ensemble that enables the system to assess both the form and the meaning of artworks and combine low-level visual characteristics with high-level aesthetic purpose. The subsections below present the major components of learning and the mathematical formulations. The feature extraction pipeline is the initial step in the algorithmic design, and it uses convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and vision transformers (ViTs) to learn to explore visual features based on the portfolio pictures to cover the discriminative visual features. The image of an artwork Ii is processed by a pretrained CNN backbone which generates feature maps containing texture, color as well as composition balance. It has the visual representation as:

![]()

And vi is the embedding vector of a d dimensional latent space. ViT modules further augment these representations by computing non-local dependencies and hierarchical patches among patches and allow the model to learn style coherence at levels above correctly aligning the model with pixel free features. In parallel with the visual extraction, semantic and textual embedding network takes artist statements as illustrated in Figure 4, artwork titles, and thematic annotations with a transformer-based encoder, like the language module of BERT or CLIP. The textual encoded cue (ti) is a representation of linguistic and conceptual hints:

![]()

When (Si) is a textual description of artwork (Ii). Normative contrastive learning is used to align the visual and textual embeddings in an overlapping multimodal latent space. The joint goal reduces the cosine distance between visual-textual embeddings that are paired whereas maximizing between the mismatched pairs:

![]()

And τ is an inverse-temperature parameter, which corresponds to the sharpness of similarity and sim(vi,ti is the cosine similarity. On the basis of these multimodal embeddings, the aesthetic scoring model provides a composite model of the aesthetic score (Ai) of each piece of artwork in terms of balance, novelty, emotional intensity, and cultural background. In this score, weighted variables are used:

![]()

In which (Q) is the visual quality (sharpness, symmetry), (C) is the conceptual coherence, (E) is the emotional expressiveness estimated through affective features and (D) is the diversity in terms of other items in the portfolio. The weights are optimized using expert-labeled data by tuning the weights through the curator feedback and regression. In addition to this scoring process, the Recommendation and Curation Optimization Layer utilizes the reinforcement learning (RL) to optimize portfolio assembling depending on dynamic feedback. The variables are state (st) (holds curated portfolio), action (at) (adding or reordering an artwork) and reward (rt) (audience encounter or satisfaction of the curator). The goal of the agent is to maximize the cumulative reward that should be expected:

![]()

In which, π(at| st )

represents the policy function and ( g ) is a discount

rate. The policy gradients or Q-learning methods modify the policy to the

actions which contribute to the increase of engagement diversity and aesthetic

coherence. This process converts algorithmic curation policies to human

feedback policies in many repetitions and allows adaptive co-evolution between

artistic and audience preferences.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Hybrid Learning Pipeline for

Intelligent Curation (CNN–Transformer–RL Integration)

Learning models are trained in a multi-phase regime: the models are trained in a stage of supervised during the pretraining using labeled aesthetic datasets, fine-tuning using contrastive objectives, and adapting during the learning phase very long, which is utilizing online responses. The ultimate synthesized model thereby develops out of the perceptual precision to a contextual interpretation and an experience personification. To assess the curatorial authenticity and interpretability of models, model evaluation is performed using quantitative measures, which include precision, recall, F1-score, normalized discounted cumulative gain (nDCG), as well as qualitative human expert ratings.

6. Portfolio Evaluation Metrics and Performance Assessment

In order to be certain that the intelligent portfolio curation system works in terms of technical integrity and aesthetic plausibility, a multi-level assessment model is used. The precision metric is used to measure the number of recommendations made by the system that were in fact relevant and the recall used to determine the level at which the system can retrieve all the relevant items in the dataset. The F1-score is a possible compromise between the two, and they are defined as:

![]()

Where, P=TP+FPTP, and R=TP+FNTP, TP, FP and FN are the true positives, false positives and false negatives respectively. The nDCG metric is a common metric in ranking-based tasks, used to assess the positional relevance of results of the curation by comparing the ranking of results in a system with the ideal rankings of curators, to the degree to which the AI would rank results as the human experts do and the consistency of the results in theme. Performance is assessed in aesthetic and semantic levels in terms of content based and perceptual metrics. The content-based metrics evaluate diversity, coherence and balance of collections curated. Stylistic dispersion through embedding dispersion is used to measure the aesthetic diversity of a curated portfolio: the Aesthetic Diversity Index (ADI):

![]()

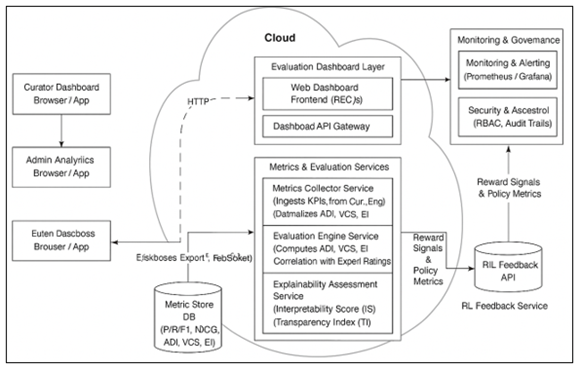

Where (vi) is artwork embeddings and v 7 is the centroid. High ADI signifies wider coverage of style, whereas low ADI signifies homogeneity of theme - both being reliant on curatorial goals. The Visual Coherence Score (VCS) on the other hand, is a consistency measure of curated collections of embeddings based on pairwise cosine similarity, which quantifies curatorial integrity and conceptual coherence as presented in Figure 5. Such steps enable one to compare quantitatively the collections created by humans and AI. The qualitative layer of evaluation involves the input of the expert opinion of art curators, teachers, and artists. Every curated collection is evaluated on four dimensions: aesthetic sense, narrative sense, originality and curatorial sense. The evaluation of these factors is done on a Likert scale (15) by the experts, and the aggregate scores are compared with the aesthetic scores obtained by the AI system (Ai) to determine congruence and deep meaning. To measure the consistency in ranking human ratings with systems, statistical correlation coefficients like the Spearman 0.001 -302 and Kendal 0.001 -302 are computed. High correlation means that the portfolios developed by the AI are highly consistent with the perception of experts.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Deployment Diagram for Evaluation

& Feedback Dashboard Architecture

7. Discussion

Experimental results of the above case studies have shown that artificial intelligence can be not a substitute of human curatorship but a cognitive accomplice that may supplement the curatorial experience. This part summarizes those results to explore the strengths, weaknesses, ethical consequences of the emerging human-AI co-curation paradigm, and place it in the context of wider discussion of authorship, authenticity, and aesthetical judgments.

7.1. Strengths: Expanding the Curatorial Spectrum

The greatest advantage of the AI-enhanced curation is its ability to promote scale, sensitivity, and serendipity. A machine learning model can be used to analyze thousands of artworks at once, and it can recognize latent stylistic and emotional connections that even a human eye cannot detect.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Comparative Case Study Outcomes Across Scenarios |

||||

|

Scenario |

Primary Objective |

AI Contribution |

Human Role |

Key Insights |

|

Solo-Artist

Retrospective |

Chronological and

stylistic synthesis |

Pattern recognition

across creative phases |

Narrative validation

and contextual framing |

AI rediscovered early

thematic precursors |

|

Multi-Artist

Exhibition |

Cross-artist

conceptual linking |

Ontology-driven

thematic clustering |

Conceptual curation

& theme balancing |

AI enhanced

cross-cultural coherence |

|

Personalized Audience

Curation |

Adaptive

recommendation for individuals |

RL-based behavioral

learning |

Oversight and

interpretive approval |

AI improved retention

& personalization |

|

Ethical Oversight

Integration |

Ensuring fairness

& transparency |

Explainability and

bias audit modules |

Governance &

accountability review |

Balanced trust between

system & curator |

In multi-artist shows, the analytical spectrum of AI allows a more profound integration of the exhibition theme, and diversity and coherence are balanced. Using multimodal embeddings and knowledge graphs, the system can make relationships between works of art that appear to have little to do with each other: geographically, medium, etc., which the conventional curation process, limited in time or familiarity, could not see. At the same time, the aspect of audience curation under personalisation highlights the democratizing possibilities of AI, which can provide unique viewers with adaptive paths of viewing works of art. By showing art in contextual, emotionally appealing series, such personalization facilitation encourages accessibility and inclusivity, boosting engagement and the level of education.

These strengths, collectively, lead to a model of curatorial intelligence functioning at three levels, namely, perceptual enhancement (enhancing both visual and semantic analysis), narrative scaffolding (generating interpretive connections among works), and adaptive mediation (learns as a result of audience response). Such an inter-level teamwork redefines curation as dynamic process of feedback as opposed to a form of selection as such.

7.2. Limitations: Boundaries of Algorithmic Interpretation

In spite of these successes, there are inherent shortcomings of the existing system that lie in the technical and philosophical constraints of the system. Algorithms of curation are still conditioned on the quality and representativeness of the training data which can have stylistic biases towards the prevailing art movements or Visual tradition. This can be neutralised using the metrics of aesthetic diversity, whereas machine recognition of the nuances of culture and history, including regional symbolism or spiritual abstraction, is still limited.

In addition, the interpretive richness of AI is also limited by the quantifiable characteristics. Models can compose, find a harmony and even a feeling through embeddings of data, but they do not have the real context consciousness of knowing the socio-political, cultural and autobiographical contexts that constitute the intent of a particular artist. The AI system can, therefore, replicate aesthetic reasoning but not philosophy. Clients in the case studies also reported that the explanations provided by the AI lacked technical decomposability but the poetic or narrative rationale behind their own human curatorial logic. This implies that tomorrow’s systems have to include explainable reasoning patterns that would be able to explain not only what the AI chooses, but why it has conceptual significance.

7.3. Ethical and Philosophical Considerations

Incorporating AI into art curation is presented with pressing issues of ethics of authorship, accountability and cultural equity. Who is the owner of the curatorial output of hybrid systems is it the human curator, the AI designer, or the aggregate data of participating artists? This kind of ambiguity makes intellectual property systems harder and requires new criteria of attribution of algorithms. Moreover, there is a threat of algorithmic bias to cultural representation. The system may reinforce the popular aesthetics or Western visual grammars without special effort in opposition to indigenous or experimental or under-documented art forms. This is necessary in order to establish inclusive datasets and curatorial audits that will help to stop homogenization of cultural expression by algorithms.

Lastly, there is an epistemic issue: AI models can be trained on engagement data, which, unintentionally, can equate popularity and artistic value and strengthen attention economies and not aesthetic discovery. Human curatorial position, as such, is necessary, as the ethical and intellectual rigor as a moral and cultural compass that manages the algorithmic decision-making. The resulting paradigm can be described as not AI as curator, but AI with curator the co-evolutionary framework where algorithms heavily offer analytical structures and human beings add interpretive level insights.

7.4. Toward Symbiotic Curation Futures

The future of the human-AI co-curation is in creating symbiosis relationships, in which both parties are constantly learning out of mutually beneficial relationships. The reinforcement learning agents have the ability of incorporating modifications made by curators as moral and artistic preferences in defining reward functions, which can be appreciative of cultural diversity and originality in addition to engagement metrics. At the same time, the pattern discovery can also be used by the curators in order to test their assumptions and make their aesthetic awareness more grand. This is where the real art of smart curation lies not in the automation of any type of curation but in collaboration the process of synthesis of both computational knowledge and human imagination and proving the boundaries of the possibilities of perceiving, placing, and experiencing art in the digital age.

8. Conclusion and Future Directions

In the case of intelligent curation, digital art management is redefined through the approach of making artificial intelligence a creative partner and not a technological competitor. The system is enhanced with curatorial results which is a balance between analytical accuracy and artistic articulation through multimodal analysis, reinforcement learning and human machine interaction. The case studies including individual retrospectives, multi-artist shows, and personalized experiences of the audience illustrate the potential of AI to reveal latent aesthetic correlations, increase the thematic intelligibility, and respond dynamically to the interaction with the audience without losing its authenticity. In its core, intelligent portfolio curation is an act of cognitive extrapolation of curatorship, and it allows one to reason on visual, textual, and emotive levels. Reinforcement learning turns curation into a structured process of constructive feedback, which improves interpretive precision in the process of interaction. The results of the evaluation prove that the balance of the framework between precision, inclusiveness, and transparency rates is human-aesthetic, notwithstanding the restrictions of the computational abilities. However, AI usage poses ethical and cultural dilemmas of authorship, bias and responsibility. The model of co-curation has to conform to aspects of fairness, explainability, and inclusivity that will tolerate equitable representation and respect to culture. Future studies ought to go a step further to describe explainable curation models (XAI-C), blockchain-based provenance systems, and decentralized adaptive networks in which artists, curators, and AI agents interact in a symbiotic way. Smart curation is the future that will turn exhibition design into the synthesis of knowledge capacity, a combination of computational logic with human understanding to generate participatory, transparent, and dynamic structures of art in the era of artificial intelligence.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Aslan, S., Castellano, G., Digeno, V., Migailo, G., Scaringi, R., and Vessio, G. (2022). Recognizing the Emotions Evoked by Artworks Through Visual Features and Knowledge Graph-Embeddings. In Image Analysis and Processing – ICIAP 2022 (Vol. 13373, pp. 129–140). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13321-3_12

Bose, D., Somandepalli, K., Kundu, S., Lahiri, R., Gratch, J., and Narayanan, S. (2021). Understanding of Emotion Perception From art. Arxiv Preprint arXiv:2110.06486.

Dawson, A. (2020). Instagram Turns Ten: How the World’s Favourite Photo App Disrupted the Art Market. The Art Newspaper.

Dolan, R., Conduit, J., Frethey-Bentham, C., Fahy, J., and Goodman, S. (2019). Social Media Engagement Behavior: A Framework for Engaging Customers Through Social Media Content. European Journal of Marketing, 53, 2213–2243. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-03-2017-0182

González-Martín, C., Carrasco, M., and Wachter Wielandt, T. G. (2024). Detection of Emotions in Artworks Using a Convolutional Neural Network Trained on Non-Artistic Images: A Methodology to Reduce the Cross-Depiction Problem. Empirical Studies of the Arts, 42, 38–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/02762374231163481

Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y., and Courville, A. (2016). Deep Learning. MIT Press.

Imran, S., Naqvi, R. A., Sajid, M., Malik, T. S., Ullah, S., Moqurrab, S. A., and Yon, D. K. (2023). Artistic Style Recognition: Combining Deep and Shallow Neural Networks for Painting Classification. Mathematics, 11, Article 4564. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11224564

Lee, S. G., and Cha, E. Y. (2016). Style Classification and Visualization of Art Painting’s Genre Using Self-Organizing Maps. Human-Centric Computing and Information Sciences, 6, Article 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13673-016-0063-4

McIntosh, M. J., and Morse, J. M. (2015). Situating and Constructing Diversity in Semi-Structured Interviews. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 2, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393615597674

Medjani, J., Nadeau, J., and Rutter, R. (2019). Social Media Management, Objectification and Measurement in an Emerging Market. International Journal of Business and Emerging Markets, 11, 288–311. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBEM.2019.102654

Moulard, J. G., Rice, D. H., Garrity, C. P., and Mangus, S. M. (2014). Artist Authenticity: How Artists’ Passion and Commitment Shape Consumers’ Perceptions and Behavioral Intentions Across Genders. Psychology and Marketing, 31, 576–590. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20719

Mughal, R., Polley, M., Sabey,

A., and Chatterjee, H. J. (2022). How Arts, Heritage and Culture can Support Health

and Wellbeing Through

Social Prescribing. National Association of School Psychologists.

Serota, N. (2023). Introducing our strategy: Let’s create. Arts Council England.

Tashu, T. M., Hajiyeva, S., and Horvath, T. (2021). Multimodal Emotion Recognition from Art Using Sequential Co-Attention. Journal of Imaging, 7, Article 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging7080157

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.