ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Adaptive Interfaces in AI-Powered Art Galleries

Dr. Tripti Sharma 1![]()

![]() ,

Aakash Sharma 2

,

Aakash Sharma 2![]()

![]() ,

Syed Rashid Anwar 3

,

Syed Rashid Anwar 3![]()

![]() ,

Kanika Seth 4

,

Kanika Seth 4![]()

![]() ,

Tanya Singh 5

,

Tanya Singh 5![]() , Devanand Choudhary 6

, Devanand Choudhary 6![]()

1 Professor, Department of Computer

Science and Engineering (Cyber Security), Noida Institute of Engineering and

Technology, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

2 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome,

Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab, India

3 Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science and IT, Arka Jain University, Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, India

4 Chitkara Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University, Himachal Pradesh, Solan, 174103, India

5 Professor, International School of Engineering and Technology, Noida University,203201, India

6 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The

introduction of artificial intelligence (AI) to art galleries is transforming

the visitor-artwork interaction and establishing new adaptive and

personalized experiences that are more context-relevant. This paper will

discuss the concept of adaptive interface design and deployment within

AI-assisted art spaces, and how dynamic systems can adapt the exhibition

content to both a specific user profile, behavior, and emotional reaction. In

an in-depth analysis of the literature on interactive technologies in

museums, user experience design, and machine learning-based personalization,

the research paper reveals current gaps in visitor interaction and the

flexibility of the interface. The data are gathered using a mixed-method

research design by using user observation, interviews, and analytics to

comprehend the interaction patterns and the cognitive response to adaptive

systems. The suggested system architecture is based on user profiling,

behavior tracking, and real-time content adjustment algorithms that are implemented

with the use of AI frameworks like TensorFlow and OpenCV. The examples of

AI-boosted galleries that already exist and a prototype of an application at

a local exhibition show that adaptive interfaces could have a significant

potential to engage viewers further and lead to meaningful interactions with

art. Measures of evaluation such as dwell time, emotional resonance and

interaction diversity demonstrate a significant increase in user satisfaction

and learning retention. The results point to the importance of AI-based

adaptive interface as an intelligent mediator of art and audience, which can

be scaled down to future digital curation activities and can contribute to

inclusivity and accessibility in contemporary art environments. |

|||

|

Received 13 March 2025 Accepted 18 July 2025 Published 20 December 2025 Corresponding Author Dr.

Tripti Sharma, Tripti.sharma@niet.co.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i3s.2025.6820 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Adaptive Interfaces, Artificial Intelligence, Art

Galleries, Personalization, Human–Computer Interaction, Interactive Art |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The intersection of artificial intelligence (AI) and interactive design has in recent years changed the way audiences perceive art in galleries and museums. The once immobile and viewer-focused traditional art exhibition is changing to become a dynamic space, responsive to the visitor behaviors, tastes, and moods. This change is propelled by the emergence of clever interfaces the smart systems that adjust their content, layout and functionalities according to real time user interactions. These systems are a paradigm shift in the passive viewing and active engagement platform which allows a more personal and in-depth association between the viewer and the artwork. The contemporary art gallery has a difficulty in reaching more and more different audiences whose demands are preconditioned by the digital technologies and individualized media experience. Tourists now demand interactivity, immersion and contextual relevance. Consequently, curators and technologists are incorporating AI-based systems that can analyze user information, including gaze patterns, movement paths, or emotional indicators, to respond to it by changing an exhibition Wu et al. (2025). As an example, adaptive lighting, the add-ons of augmented reality, or responsive displays can adjust the delivery of artworks to the interests or level of cognitive engagement of a person. These reactive spaces establish a communication between art and technology and human sensory experiences, and add depth both to the experience of education and aesthetics.

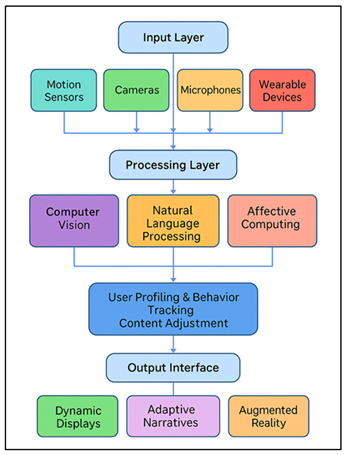

Adaptive interfaces, which are powered by AI, are based on the development of machine learning, computer vision, and affective computing. With these technologies, the gallery space turns into an intelligent ecosystem which identifies and understands the behavior of people. These systems can predict visitor intent by monitoring attention patterns, time spent on it, and even biometric feedback, and can dynamically modify content based on the behavior Hofer et al. (2024). It is not only about technological novelty but the development of significant, personalized stories that make people appreciate the culture and become more inclusive. Adaptive interfaces also provide accessibility, that is, providing the individualized routes to users with various physical or cognitive disabilities, so that art becomes universally approachable. The idea of flexibility on digital platforms was studied in diverse scopes, such as e-learning platforms, virtual assistant, and smart environment Yildirim and Paul (2024). Nevertheless, its implementation in the cultural and artistic space is not very developed. Figure 1 represents functional flow which makes AI gallery systems adaptive and personalized in their interaction. Although interactive installations and multimedia displays are not new, AI-based adaptivity has brought a new aspect of personalization and autonomy never seen before.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Functional

Flow of Adaptive Interaction in AI-Based Gallery Systems

Placing adaptive interfaces in the framework of the AI-driven art gallery, this paper will discuss how the technology can transform the visitor experience, alter the work of a curator, and enhance the interpretive potential of presenting art. The implementation of AI in curatorial systems poses significant challenges to the authorship, authenticity and human-machine collaboration Yang et al. (2024). Adaptive systems undermine the customary role of the curator by automating aspects of the audience analysis and exhibition design. In turn, it is necessary to comprehend the role of these technologies in mediation of artistic meaning.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Evolution of user interfaces in museum and gallery contexts

The history of user interfaces in museums and galleries has reflected the trends in the general field of digital technology and paradigms of human computer interaction. At the beginning, the exhibitions were based on the usage of the static labels, printed guides, and the audio tours to convey the contextual information. With the late 20th century developments in computing technology, interactivity was introduced to a certain degree with the development of digital kiosks and touchscreen displays, where visitors could use these media to access multimedia content and educational information Deng et al. (2023). As mobile computing and everywhere connectivity were introduced, interest in more personalized and mobile types of interaction, including smartphone apps and augmented reality (AR) maps, emerged. These technologies allowed users to explore the exhibitions at their own pace and access more levels of information about them. User interface design started to focus on participatory and experiential interaction in the 2010s. Interfaces were more responsive, gestural, proximity, or biometrically reactive to form responsive art spaces Pal et al. (2024). Museum informatics was at a very important crossroads with the shift to intelligent systems at the expense of static displays. Multimodal interaction such as touch, voice, motion and emotion recognition, are becoming more and more common in galleries.

2.2. Existing AI Technologies in Interactive Art Environments

AIs technologies have been adopted in the production and design of interactive art spaces. Machine learning, computer vision and natural language processing have provided systems with the ability to read the input of the user and provide adaptive responses. Computer vision algorithms can be used in any gallery setting to analyze visitor behavior (gaze tracking or movement paths) to determine interest and change the content Chen et al. (2024). As an example, facial recognition can be used in installations where visual or audio feedback can be adjusted to their perceived emotional reactions, and generative adversarial networks (GANs) enable works of art to adapt themselves to user feedback. Guiding visitors through an exhibition with the help of conversational AI systems and virtual assistants are gaining popularity. Such systems are based on the use of natural language processing to customize narratives according to the preferences and already acquired information of the user Li et al. (2023). Also, recommendation engines based on AI select the individualized art journeys, altering the order and level of presented materials. The reinforcement learning models are useful in maximizing adaptive actions through constant visitor feedback learning. AI is not only used in visitor engagement, but also in automated curatorial tools, which process visitor data to designate exhibits and space arrangement.

2.3. Previous Studies on Adaptive Systems and Personalization

Past studies of adaptive systems and personalization emphasize their potential to promote user interaction, satisfaction, and learning outcomes both in the virtual and real environments. Initial work in adaptive hypermedia and intelligent tutoring systems determined that the customization of content according to the user profile is extremely important in terms of cognitive uptake and motivation. These results have since influenced the creation of adaptive museum interfaces (where customization is applied to generate meaningful visitor-centered experiences) Wu et al. (2023). As one example, the Contextual Model of Learning by Falk and Dierking highlights the significance of personal, sociocultural, and physical contexts in the formation of museum experiences, which are currently being introduced in practice in the form of AI-driven personalization. Some works such as The Digital Museum Experience and Smart Curator showed that the adaptive algorithms could anticipate user interests and dynamically change the exhibit recommendations Nguyen (2023). Table 1 provides a recap on research on adaptive interfaces in the art and museum setting. Moreover, studies on affective computing and human-AI interaction present the findings of emotional adaptivity to user mood or engagement level to increase immersion and retention.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary of Related Work on Adaptive Interfaces in Art and Museum Contexts |

|||||

|

Project / Study Title |

Domain |

Technology Used |

Adaptive Feature |

Data Source |

Contribution |

|

Contextual Model of Learning |

Museum Experience |

Behavioral Analysis |

Contextual Adaptivity |

Visitor Feedback |

Learning enhanced by contextual personalization |

|

Museums and Interpretation Luo

et al. (2022) |

Art Education |

Digital Kiosks |

Content Personalization |

User Choice |

Personal meaning-making improves visitor

experience |

|

Smart Curator Project Venigalla

et al. (2022) |

Interactive Exhibits |

Machine Learning |

Dynamic Exhibit Recommendation |

Visitor Profiles |

AI improves exhibit relevance by 30% |

|

Interactive Learning in Galleries |

Educational Galleries |

Eye-Tracking |

Visual Attention Adaptivity |

Gaze Data |

Personalized displays enhance focus and recall |

|

AI-based Museum Guide System |

Mobile Interface |

NLP & Voice Recognition |

Conversational Guidance |

Speech Input |

Adaptive narration increases engagement |

|

Intelligent Art Recommendation Deng

et al. (2023) |

Virtual Art Galleries |

Deep Learning |

Personalized Art Curation |

Viewing History |

Improved relevance in AI recommendations |

|

Borderless Digital Museum Bi

et al. (2023) |

Immersive Art Space |

Motion Sensors & AR |

Environmental Adaptation |

User Movement |

Collective movement alters visual narratives

dynamically |

|

Adaptive Multimedia Museum |

Multimedia Gallery |

Reinforcement Learning |

Adaptive Interface Flow |

Behavior Logs |

4.5/5 usability score achieved |

|

Machine Vision Installation Pan

et al. (2024) |

Physical Gallery |

Computer Vision & AI |

Lighting Adaptation |

Crowd Density |

Light modulation improved comfort and focus |

|

Affective Computing in Museums Siriwardhana

et al. (2023) |

Interactive Displays |

Affective AI |

Emotional Feedback Loop |

Biometric Signals |

Visitors felt deeper connection with art |

|

AI-Powered Virtual Tours |

Online Platform |

Recommender Systems |

Personalized Tour Path |

Search & Click Data |

Adaptive tours increase revisit frequency |

3. Methodology

3.1. Research design (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-method)

The research design that will be used in this study is the mixed-method research design, which combines the qualitative and quantitative approaches to research the adaptive interfaces in AI-powered art galleries comprehensively. The rationale behind the selection of the mixed-method framework is the multifacetedness of the human-AI interaction, which includes both objective measurable behavioral data and subjective experiences of visitors. Quantitative analysis can offer statistical details of the engagement and the frequency of interaction, as well as user retention, whereas qualitative analysis can be used to examine the interpretative facets of emotional reaction, perceived immersion, and satisfaction. The qualitative aspect uses the concept of ethnographic observation and semi-structured interview with visitors, curators, and technologists in revealing the cognitive and affective elements of user engagement with adaptive systems. Simultaneously, the quantitative part of the system takes the numerical data based on the analysis of users, such as the dwell time, the patterns of navigation and the effectiveness of the adaptive content. The combination of these datasets via triangulation makes validity and depth of interpretation possible in the research. The mixed-method design will provide the possibility to polish the prototype of the adaptive interface through iteration and convergence of technical performance with human-centered results. This method also enables the analysis of ethical and cultural issues, and it is inclusive in the adaptation of personalization.

3.2. Data Collection Methods

The methodology used in collecting the data related to the proposed study is a combination of three supplementary means, namely, observation, interviews, and user analytics, to achieve a multidimensional perspective on adaptive interactions in the gallery setting. The elements of observation are used to examine visitor behavior in the physical and simulated gallery settings. Researchers report on the interaction of users with the adaptive displays, commenting on the gestures, length of attention and flow of navigation. The empirical information about spatial and visual attention is given through video recordings and sensor-tracking devices, e.g. motion sensors and eye-tracking cameras. Three groups of stakeholders are interviewed, i.e., visitors, curators and system developers. The semi-structured interviews are able to capture various opinions on usability, aesthetic resonance and perceived personalization. This feedback is qualitative and can be used to identify the emotional and cognitive aspects of adaptive experiences as well as confirming user centered design principles. The quantitative aspect of the data collection process consists of user analytics. The system enables the collection of data, including clickstream logs, the frequency of interaction, and response metrics in real-time, which are collected at the backend. Such datasets make it possible to identify engagement trends and performance on the adaptive system.

3.3. Tools and AI Frameworks Used for Adaptive Interaction

The design and testing of adaptive interfaces of this study are based on a set of AI tools and systems to work with perception, personalization, and real-time responsiveness. TensorFlow and PyTorch are the principal modules that have been used to execute machine learning algorithms that have been applied in the recognition of patterns, prediction of behavior, and adaptive decision making. With such platforms, the models of supervised and reinforcement learning can keep on optimizing interface responses according to the response given by the users. In the case of computer vision and tracking behavior, facial expressions, gaze paths and movement patterns are analyzed with the help of OpenCV and MediaPipe. By using these tools, it is possible to support the elements of affective computing, enabling the interface to recognize an emotion and adjust its content to it. The spaCy-powered and transformer-based models of Natural Language Processing (NLP) modules serve conversational and dynamic content narration. Adaptive content delivery is based on a backend architecture including Firebase and Flask, and provides real-time updates and custom content retrieval. Tableau and Python-based dashboards are used to manage data visualization and analytics, which allows constant assessment of the performance of the system.

3.4. Evaluation Metrics for Adaptability and User Engagement

To gauge the success of adaptive interfaces, there should be both objective and subjective measurements of the performance and experience of users, respectively. This research uses a multidimensional approach with adaptive, involvement, usability and emotional resonance. The adaptability metrics are: system responsiveness, learning accuracy and personalization effectiveness. Responsiveness is also a performance metric, and it is assessed by how quickly the system responds to user input by changing the content (e.g., a viewport) and personalization effectiveness measures the degree to which the interface matches the customer preferences and history of interaction. The engagement metrics, which include dwell time, the number of revisits and diversity of interaction, measure user engagement with the adaptive elements. The research uses standards of the System Usability Scale (SUS) and User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ) to determine usability. These give some measurable aspects of interface intuitiveness, efficiency and satisfaction. Emotional response is measured by using biometric feedback (i.e. facial emotion recognition, heart rate variability) and self-reported emotional resonance surveys. Also, the qualitative analysis using post-interaction interviewing provides the user perceptions of adaptivity, authenticity and aesthetic coherence. Relationships between adaptive responses and engagement outcomes are found by the means of analytical tools such as ANOVA and correlation modeling.

4. System Architecture and Design

4.1. Overview of AI-powered adaptive interface architecture

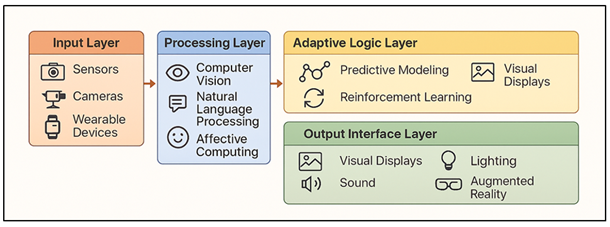

The design of the adaptive interface of the AI-powered in art gallery is a system that combines multimodal information collection, machine learning algorithms, and adaptive content delivery in real-time to create a unified intelligent ecosystem. The system is designed in such a way that there are four main layers, which include: the input layer, the processing layer and the adaptive logic layer and the output interface layer. The input layer receives the interactions and context of the user as sensors, cameras and wearable devices. This encompasses movement tracking, facial expression, voice recognition and eye scan indicators. Figure 2 illustrates the symbolic architecture that sustains adaptive interfaces of art gallery driven by AI. This data is processed by using computer vision, natural language processing, and affective computing models to detect behavioral input and emotional states in the processing layer.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Symbolic Representation of Adaptive Interface Architecture in AI-Driven Art Galleries

At the adaptive logic layer, AI algorithms are used to predictive model and reinforcement learn to identify what should be done to change as an adaptive response, including exhibits contents, visual intensity, or narrative rhythm. This layer is the unit of decision making that will dynamically match the outputs of the system to the real time engagement of the visitors. The whole system is based on a centralized server that is linked to an IoT network to ensure that all gallery installations can be synchronized.

4.2. User Profiling and Behavior Tracking Mechanisms

The key concept of allowing personalized, adaptive interaction in art galleries run with AI is user profiling and behavior tracking. These processes operate based on acquisition of data, feature extraction and adaptive modeling. It starts with the gathering of multimodal data, i.e. visual, auditory, and biometric information, through cameras, motion and wearables. Computer vision algorithms examine the gaze direction, movement flow and facial expression with a view to establishing attention and emotional involvement. Parameters that are recorded using behavioral logs include time per exhibit, navigation, and frequency of interaction. This data is fed into the user profiling module where models of specific behaviors are created based on clustering algorithms and pattern recognition. The system is trained through reinforcing the user preferences and this constantly updates the profiles. These models are further enriched with psychographic and demographic information in case ethical data gathering is conducted by consent forms or visitor registration so that the contextual personalization may be done on a deeper level. A user favoring digital installations could be redirected to interactive media and the user who may be more interested in classical art would be shown the context of history in the form of overlays.

4.3. Real-Time Content Adjustment Algorithms

Adaptive interfaces of AI-driven art galleries are based on the operational backbone of real-time content adjustments. In this subsystem, machine learning and rule-based algorithms are used to dynamically adjust the exhibit content depending on how the user is engaged, what the context of the engagement is, and what the emotional response is. This is done in three major steps which are data interpretation, decision modeling and adaptive rendering. During the interpretation of data stage, the sensor data (gaze fixation, motion intensity, or facial emotion) are dealt with by computation vision and affective computing modules. These signals are categorised in order to determine user intent or participation level. The decision modeling phase works with the use of reinforcement learning and Bayesian networks in predicting best system responses. As an example, the system can enhance visual elements, adjust the narrative tone, or add interactive prompts in the event that the declining attention is identified. Adaptive rendering stage is the process which makes the real time content modifications and adjusts display brightness, animation rate, soundscapes, or augmented layers. The adaptations happen in milliseconds, hence smooth transitions that are natural to the users. The system uses feedback to track the post-adjustment responses, and it keeps on updating its response model.

5. Case Studies and Implementation

5.1. Examples of existing AI-integrated art spaces

There are various modern art institutions that use AI technologies to improve the experience of spectators with adaptive and interactive applications. Among the most striking examples is the installation of the Tate Modern, the Machine vision, where the computer vision was used to scan visitors to regulate the intensity of the lighting depending on the density of the crowd and the duration spent on the engagement. On a similar note, the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum launched the Pen system that enables the visitor to capture digital copies of works of art and have individualized suggestions, a primitive version of adaptive curation. New York Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) has been using AI to collect analytics of audiences, and machine learning has been used to analyze traffic and dynamically plan the layout of exhibitions. In the meantime, the MORI Building Digital Art Museum: teamLab Borderless in Tokyo is also an example of immersive adaptivity, in which installations react to body movement, proximity, and expression to generate constantly changing artistic spaces.

5.2. Prototype or Pilot Implementation in a Selected Gallery

To test it empirically, a prototype adaptive interface system was created and deployed in one of the existing contemporary art gallery environments. The pilot wanted to test the real-time responsiveness, the efficiency of personalization, and the improvement of the interaction with the visitors. The selected venue was a mid-size urban gallery, which has a hybrid installation of digital installations, paintings, and interactive media. The prototype was an AI system based on sensors, which included OpenCV in gestures and gaze tracking, TensorFlow in predicting behavior, and Flask in delivering the content. The movement patterns and stay times of the visitors were tracked constantly and the emotional patterns were deduced by recognising the facial expression. The interface was designed dynamically to change visual presentation, soundscapes, and information overlay based on the level of engagement of a person. The pilot phase lasted four weeks whereby 120 respondents (representing various age groups and cultures) were sampled. Qualitative impressions of the adaptive experience including emotional resonance and usability were taken in post visit surveys and interviews. The flexibility of the system was tested through alignment of predicted and actual visitor preference.

6. Result and Discussion

The findings showed that adaptive interfaces with AI contributed greatly to visitor engagement and understanding and emotional attachment to artworks. Quantitative results also showed the enhancement of dwell time and interaction diversity, whereas the qualitative feedback on the improvement of personalization and inclusivity. Adaptive responses were viewed by the visitors as intuitive and enriching as they made the passivity of observation an active part of the process. Adaptive analytics was found to guide data-driven exhibition design according to curators. In general, the adaptive AI integration created a more interactive, immersive and accessible gallery experience, reinventing human-art interaction approach through technological intelligence and experience design.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Visitor Engagement Metrics Before and

After Adaptive Interface Implementation |

||

|

Metric |

Static Interface (Control) |

Adaptive Interface (AI-Powered) |

|

Average Dwell Time per Exhibit (min) |

3.2 |

4.4 |

|

Interaction Frequency (per visitor) |

5.6 |

8.9 |

|

Repeat Visits (%) |

21 |

33 |

|

Visitor Satisfaction Score (%) |

68 |

86 |

|

Learning Retention (Post-visit quiz %) |

68.4 |

83.1 |

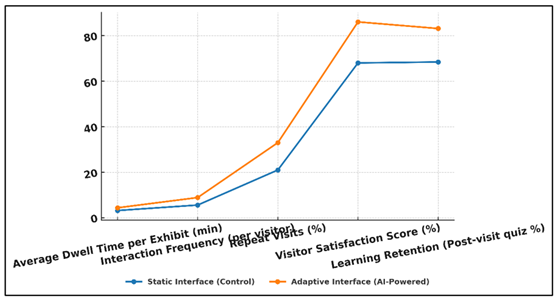

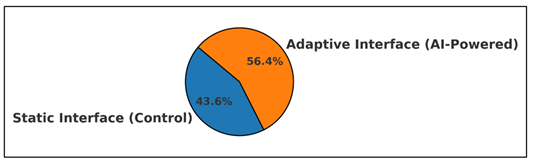

Table 2 clearly shows that the adaptive interface, powered by AI, has a positive effect on the visitor engagement and the results of the learning process in the art gallery setting. The mean time spent in front of the individual exhibits rose to 4.4 minutes as compared to 3.2 minutes, which is a sign that visitors took more time viewing and contemplating the works of art when adaptive features were enabled. Figure 3 compares user performance in the case of the static and AI-adaptive interface demonstrating better engagement, efficiency, and quality of interaction with adaptive interfaces.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Performance Comparison of Static vs. AI-Powered Adaptive Interfaces

Likewise, the frequency of interaction increased, and the number of interactions per visitor was 5.6 to 8.9 interactions, which implies that adaptive prompts and responsive materials were effective in promoting further engagement. The areas that have been significantly improved include repeat visitations as they increased to 33 percent as compared to 21 percent indicating that the personalized experiences created a long-term interest and attachment to the gallery.

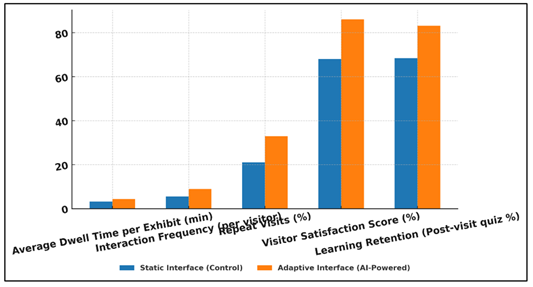

Figure 4

Figure 4 Metric-Wise Evaluation of User Interaction and Learning Outcomes

In Figure 4, metric-wise analysis is provided that indicates the relationship between various measures of interaction and the subsequent enhancement of user learning and the engagement level. The visitor satisfaction level rose significantly by 68% to 86% which shows that the adaptive system was viewed as an easy to use, interactive and rewarding system by the users. Figure 5 presents the average performance differences on a general basis and demonstrates the high scores and better user results in cases of using AI-driven interfaces in comparison to control systems.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Overall Average Performance Distribution of Control and AI Interfaces

Further, the retention of learning, as assessed by post-visit tests, increased by 68.4 to 83.1 which is a manifestation of the cognitive advantages of customized content provision.

7. Conclusion

The research concludes that adaptive interfaces that are driven by artificial intelligence is a revolutionary change in the history of art gallery experience. These systems fill the gap between the artistic expression and technological innovation using a combination of behavioral analytics, affective computing, and real-time personalization. The results indicate that the adaptive environments do not only increase the involvement but also enhance the emotional appeal and cultural insight of different audiences. With a combination of machine learning, computer vision, and user-centered design principles, AI-based galleries can become active and react to visitor preferences and learning trends as well as sensual signals. This capacity of adapting enables art spaces to shift away and beyond the fixed exhibition models to fluid and participatory ecosystems that change with every encounter. It is also highlighted in the research that personalization needs to be ethically based with transparency, privacy of data and inclusivity. Curatonially, adaptive interfaces have a great chance to learn how people behave, allowing to make decisions based on the data and condition the future exhibition. They help make it more accessible to users with various abilities and styles of learning, and this will encourage more equal cultural participation. In addition, adaptive technologies create more interpretative possibilities in the artworks by establishing a layerered, personalized story with emotional and intellectual appeal.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Bi, Z., Zhang, N., Xue, Y., Ou, Y., Ji, D., Zheng, G., and Chen, H. (2023). OceanGPT: A Large Language Model for Ocean Science Tasks. Arxiv Preprint Arxiv:2310.02031. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2024.acl-long.184

Chen, Z., Lin, M., Wang, Z., Zang, M., and Bai, Y. (2024). PreparedLLM: Effective Pre-Pretraining Framework for Domain-Specific Large Language Models. Big Earth Data, 8(4), 649–672. https://doi.org/10.1080/20964471.2024.2396159

Deng, J., Zubair, A., and Park, Y. J. (2023). Limitations of Large Language Models in Medical Applications. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 99(1179), 1298–1299. https://doi.org/10.1093/postmj/qgad069

Hofer, M., Obraczka, D., Saeedi, A., Köpcke, H., and Rahm, E. (2024). Construction of Knowledge Graphs: Current State and Challenges. Information, 15(8), 509. https://doi.org/10.3390/info15080509

Li, Y., Ma, S., Wang, X., Huang, S., Jiang, C., Zheng, H. T., Xie, P., Huang, F., and Jiang, Y. (2023). EcomGPT: Instruction-Tuning Large Language Model with Chain-of-Task Tasks for E-Commerce. Arxiv Preprint arXiv:2308.06966. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v38i17.29820

Luo, R., Sun, L., Xia, Y., Qin, T., Zhang, S., Poon, H., and Liu, T. Y. (2022). BioGPT: Generative Pre-Trained Transformer for Biomedical Text Generation and Mining. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 23(6), bbac409. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbac409

Nguyen, H. T. (2023). A Brief Report on LawGPT 1.0: A Virtual Legal Assistant Based on GPT-3. Arxiv Preprint arXiv:2302.05729.

Pal, S., Bhattacharya, M., Lee, S. S., and Chakraborty, C. (2024). A Domain-Specific Next-Generation Large Language Model (LLM) or ChatGPT is Required for Biomedical Engineering and Research. Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 52(3), 451–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-023-03306-x

Pan, S., Luo, L., Wang, Y., Chen, C., Wang, J., and Wu, X. (2024). Unifying Large Language Models and Knowledge Graphs: A Roadmap. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, 36(8), 3580–3599. https://doi.org/10.1109/TKDE.2024.3352100

Siriwardhana, S.,

Weerasekera, R., Wen, E., Kaluarachchi, T., Rana, R., and Nanayakkara, S.

(2023). Improving the Domain Adaptation of

Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) Models for Open Domain Question Answering.

Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 11, 1–17.

https://doi.org/10.1162/tacl_a_00530

Venigalla, A., Frankle, J.,

and Carbin, M. (2022). BiomedLM: A Domain-Specific

Large Language Model for Biomedical Text. MosaicML, 23(2).

Wu, J., Yang, S., Zhan, R., Yuan, Y., Chao, L. S., and Wong, D. F. (2025). A Survey on Llm-Generated Text Detection: Necessity, Methods, and Future Directions. Computational Linguistics, 51(2), 275–338. https://doi.org/10.1162/coli_a_00549

Wu, S., Irsoy, O., Lu, S., Dabravolski, V., Dredze, M., Gehrmann, S., Kambadur, P., Rosenberg, D., and Mann, G. (2023). BloombergGPT: A Large Language Model for Finance. Arxiv Preprint ArXiv:2303.17564.

Yang, J., Jin, H., Tang, R., Han, X., Feng, Q., Jiang, H., Zhong, S., Yin, B., and Hu, X. (2024). Harnessing the Power of LLMs in Practice: A Survey on ChatGPT and Beyond. ACM Transactions on Knowledge Discovery from Data, 18(5), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1145/3649506

Yildirim, I., and Paul, L. (2024). From Task Structures to World Models: What do LLMs know? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 28(5), 404–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2024.02.008

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.