ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

AI as a Medium in Conceptual Art Practice

Dr. Peeyush Kumar Gupta 1![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Ankayarkanni B. 2

,

Dr. Ankayarkanni B. 2![]()

![]() ,

Amit Kumar 3

,

Amit Kumar 3![]()

![]() ,

Kuldeep Dhiman 4

,

Kuldeep Dhiman 4![]() , Romil Jain 5

, Romil Jain 5![]()

![]() ,

Amrut Ramchandra Pawar 6

,

Amrut Ramchandra Pawar 6![]() , Dipti Nitin Dixit 6

, Dipti Nitin Dixit 6![]()

1 Assistant Professor, ISDI - School of

Design and Innovation, ATLAS Skill Tech University, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

2 Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Sathyabama Institute of Science and Technology, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

3 Centre of Research

Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab, India

4 Assistant Professor, International School of Sciences, Noida University,203201, India

5 Chitkara Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University, Himachal Pradesh, Solan, 174103, India

6 Department of CSE (AIML), Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

This paper

sets out to review the advent of artificial intelligence as an important

medium in modern conceptual art practice, with particular reference to its

ability to both extend and confuse the traditional operating assumption of

ideas being the primary element in conceptual art practice. The study is

based on the historical development of conceptualism, starting with the early

linguistic and systemic arts and moving to the subsequent computational

experimentalism, which orients AI to a tradition of artistic and

process-oriented approaches, in which processes, instructions, and networks

of meaning take the place of conventional object-based production. The

distinctive language, image, and symbolic manipulatory skills of AI present

new forms of authorship, autonomy, and indeterminacy and provide artists with

the opportunity to create works that predetermine system-directed meaning,

algorithmic patterning, and computational aesthetics. By presenting the

history of algorithmic practices and the current case study, the paper will

show that AI is not only a technical tool but also an active conceptual agent

that can act to construct the propositions of art. This incorporates its role

as partner, actor, and even proxy author, and leads to a rethinking of the agency

of the creative and agency, and purposefulness. The theoretical consequences

of the changes throw down challenges to the accepted versions of

interpretation, work of art, and the limits of the intelligent in the

artistic frames. Finally, the paper concludes that AI has a transformative

potential to conceptual art that relates to the possibility of producing

novel types of ideas, speculative questions, and bringing immaterial ideas to

life. |

|||

|

Received 29 February 2025 Accepted 27 June 2025 Published 20 December 2025 Corresponding Author Dr.

Peeyush Kumar Gupta, peeyush.gupta@atlasuniversity.edu.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i3s.2025.6817 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Artificial Intelligence, Conceptual Art, Authorship,

Computational Aesthetics, Algorithmic Art, Creative Agency |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

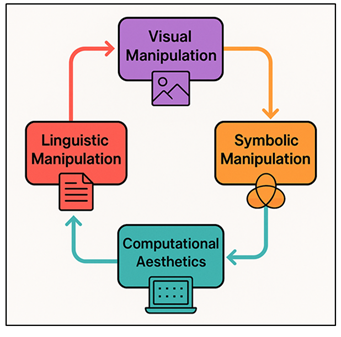

The fast adoption of artificial intelligence into artistic creation has brought about a paradigm shift in understanding the role of medium, idea, and authorship as the primary issues of the conceptual art since its introduction in the late 1960s. Although the early conceptual artists attempted to dematerialize the art object by focusing on ideas, instructions and linguistic propositions, AI presents a new type of immaterialism but generative medium which is capable not only of generating images, texts and forms, but also of modeling patterns of thought, inference, and symbolic relation. This change calls into question a new conceptualization of the meaning of art being conceptual in a period where the computer systems themselves have the ability to produce, manipulate and comprehend conceptual content. The growing availability and complexity of AI in the form of large language models to neural generative systems have widened the artistic practice beyond what was already understood as algorithmic or rule-based creation systems. Contrary to the previous computational systems that ran pre-programmed instructions, AI provides some degree of conditional autonomy: it is able to generalize data, recombine concepts, simulate dialogic thinking, and add the element of surprise to the creative process. To conceptual artists, this kind of behavior is a resonance and a continuation of strategies employed historically to disrupt authorship, challenge knowledge systems and prefigure the methods of meaning construction Walczak and Cellary (2023). AI is not, however, just a means but an intermediary in relationship to which its conceptual value is based on the idea of an active participant in a logic of the piece of art. The development of AI-based art also makes the old arguments on artistic agency difficult. Conceptual art has continually put in doubt the concept of the individual genius-artist through foregrounding instructions, systems, and collective interpretation. Figure 1 presents a generalized flow of ideas to show how AI systems generate art. In AI, the agency is further displaced: machine outputs produce contents in which the artist is not always expected to know, and the training data, computational architectures and algorithmic constraints have a systemic effect on meaning-making Kalniņa et al. (2024).

Figure 1

Figure 1 Conceptual

Pathways of AI-Driven Art Production

This brings up the issue of whether AI is a collaborator, assistant, co-author or even a performer when it comes to the conceptual framework of the piece. The resulting artworks tend to be pegged on the relationship of tension between the intent of the human and the workings of the machine to produce new conceptual landscapes based on ambiguity, distributed authorship and aesthetics of computation. Simultaneously, the medium of AI reinstates the conceptual art having the obligation to question the frameworks within which language, images, and knowledge work Alotaibi (2024). The past conceptual artists employed linguistic play, bureaucratic processes and systems analysis to uncover the hidden processes that define knowledge. The AI provides a modern equivalent: its generative capabilities are based on the statistical and ideological modes of the data used to train the actual AI, rendering it as a medium, a natural encoding of the systems and prejudices of the world that created it. Artists who use AI have a chance to predict such situations and use the medium to criticize the technological infrastructures, explore the aesthetic of machine logic, or highlight the artificiality of intelligence itself.

2. Historical Context of Conceptual Art

2.1. Overview of conceptualism’s focus on ideas over objects

Conceptualism is a radical shift in the priorities of art that appeared in the late 1960s and criticized the existence of the object of art as the most important place of meaning and the idea, as the main place of its meaning. Conceptual artists like Sol LeWitt, Joseph Kosuth, Lawrence Weiner and others tried to deconstruct the conventional notions about craftsmanship, materiality and visual gratification Hutson and Lang (2023). Instead, they suggested that conceptual basis of a work, which is frequently presented in a written form or instructions or systems, should be considered the piece of art. In this context objects were made secondary and only optional manifestations or placeholders of the underlying proposition. This process of dematerialization of the art object was simultaneously a reaction to commodification of art and an attempt to move the boundaries of artistic practice to the limits that were not imposed by physical form Chiu et al. (2022). At the heart of conceptualism, there was an opinion that art could be a discipline of investigation and not a visual production sphere. The strategies used by artists were based on linguistics, logic, philosophy and bureaucratic processes, which artists used to challenge the way of meaning production and perception. The focus on propositions as opposed to material artifacts moved the focus on the mental work of an artist and the mental work of a viewer Lim et al. (2023). Consequently, the art piece turned into a place of interaction with knowledge systems instead of a work of art. This long-standing philosophical direction, which gave ideas, instructions, and systemic thinking priority, became the foundation of subsequent artistic tendencies, which began to experiment with other mediums, such as digital, algorithmic, and eventually AI-based practices.

2.2. Evolution of Artistic Mediums within Conceptual Art Practice

Despite the fact that conceptual art has been traditionally linked to the phenomenon of dematerialization, the history of conceptual art shows that there has always been a consistent growth and transformation of artistic mediums to achieve conceptual ends. The use of language as a unit of analysis and as a sculptural substance was common in early conceptual practices that utilised text in various ways. At the same time, photographers, diagrammers, and documers employed photography, diagrams, and documentation not to express beauty but express their ability to give directions, procedures, or pieces of evidence Ernesto and Gerardou (2023). These mediated representations undermined the concept of medium specificity and proposed the value of the media as being the capacity to host or carry conceptual propositions. With the development of conceptual art, artists came to rely more on systems-based and technological media that represented or performed conceptual structures Ivanov and Soliman (2023). The medium was emphasized as a medium of operation, a system of operations and not a material substrate by the use of instructional art, performance scores, and bureaucratic operations. The developments made conceptualism connected to the new technologies cultures, which position technological as a site of meaning, and not just the instrument. Table 1 presents insights into studies that have been published on the role of AI as an approach to conceptual art. In the late twenty th and early twenty first century, conceptual art began incorporating digital media, networks, and software to a greater extent.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary on AI as a Medium in

Conceptual Art Practice |

|||||

|

Work

/ Project |

Method

/ Technology |

Conceptual

Focus |

Benefits |

Impact

on Art Practice |

Future

Trends |

|

Early

Plotter Drawings Lacey and Smith (2023) |

Algorithmic

rules, computer programs |

Systemic

aesthetics, logic |

Introduced

generative systems |

Positioned

computers as creative agents |

Revival

of rule-based generativity |

|

Matrix

Multiplications |

Early

digital computation |

Mathematical

structure |

Linking

math + aesthetics |

Expanded

computational art vocabulary |

Hybrid

symbolic–AI approaches |

|

Cubic

Limit Cao et al. (2023) |

Algorithmic

abstraction |

Formal

systems, minimalism |

Clear

demonstration of process-based art |

Influenced

later neural-gen art |

AI-driven

dynamic abstraction |

|

Instruction-based

works |

Rule

systems, language |

Idea

> object |

Foundation

for system logic |

Inspired

later algorithmic art |

AI

as autonomous executor |

|

BOB

O’Dea (2024) |

Reinforcement

learning, agents |

Autonomy,

evolving systems |

Live

simulations with behavior |

Redefined

digital performance |

Long-duration

AI ecosystems |

|

Data

Sculptures |

GANs,

neural networks |

Data

aesthetics |

Makes

invisible data perceptible |

Popularized

AI aesthetics |

Hyper-contextual

datasets |

|

Mosaic

Virus Pataranutaporn

et al. (2021) |

Custom

datasets, GANs |

Data

authorship |

Emphasized

dataset construction |

Highlighted

human shaping of AI |

Ethical

dataset building |

|

Training

Humans |

Dataset

analysis |

Surveillance

critique |

Reveals

biases in AI |

Raised

sociopolitical awareness |

Critical

AI literacy in art |

|

Spawn

Davidovitch

et al. (2024) |

Vocal

neural networks |

Human–machine

co-creation |

New

sonic vocabularies |

Expanded

AI in performance |

Adaptive

AI instruments |

|

How

Not to Be Seen |

AI,

imaging systems |

Institutional

critique |

Connects

AI + geopolitics |

Critical

discourse influence |

AI

for geopolitical mapping |

|

Synthetic

Abstractions |

Classifiers,

ML vision |

Machine

perception |

Reveals

how AI “sees” |

Bridged

ML research + art |

Interpretability-focused

art |

3. AI and Conceptual Strategies

3.1. AI’s capacity for linguistic, visual, and symbolic manipulation

Artificial intelligence presents new possibilities of manipulating linguistic, visual, and symbolic forms such that it is an exceptionally versatile medium in conceptual art. In contrast to previous algorithmic tools, which functioninged based on the process of the application of rules, modern AI systems, especially to neural networks, operate by learning statistical trends using large amounts of data. This allows them to create language that resembles human syntax, create images that have the appearance of paintings or photographs and combine symbols in the same way as to give the impression of associative or metaphorical thought Chan and Lee (2023). To conceptual artists, these capabilities create new avenues of questioning how the meaning is constructed, written and altered through the representational systems. In the manipulation of language AI is capable of producing texts that simultaneously act both as content and commentary upon language. AI allows artists to make ambiguous statements, pseudo-theoretical fragments or recursive definitions that violate the stability of interpretation Dehouche and Dehouche (2023). AI models in visual manipulation rearrange images, creating new forms by hallucinating, or reinterpretation of patterns in memory representations, which provokes the question of authenticity, perception, and what representation is. Symbolically, AI systems can subdivide categories and resembling connections and connotations and disclose the biases as well as the conceptual structures ingrained in the training material Sullivan et al. (2023).

3.2. AI’s Role in Authorship, Autonomy, and System-Driven Meaning

The introduction of AI in conceptual art essentially bests the established ideas of authorship since it is capable of obscuring the line between human will, machine agency, and systemic determinism. Historically conceptual art subverted the role of the artist as the lone creator and highlighted instructions, shared authorship or the concept as the dominant force. As shown in Figure 2, there are interactions between AI systems and authorship and artistic autonomy. AI goes beyond this usurpation of authorship by introducing a generative system that can generate content that goes beyond or off-course what the artist anticipated.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Systemic

Interactions Between AI, Authorship, and Artistic Autonomy

Consequently, the art piece is a compromise between the conceptual system of the artist and the internal logic of an algorithm, training history and computational tendencies. AI exhibits some kind of conditional autonomy: despite being programmed and instructed by human designers, its results are co-created by a complex network-based process that cannot be fully predicted and is not under the control of the artist. This independence brings a novel system-driven meaning, where the meaning of the artwork is created through the interactions of input stimuli, model structure, data biases, and inference of the algorithm. In this regard, AI does not act as much as a tool but more as a companion or an actor in the conceptual mechanism of the work.

3.3. AI-Generated Randomness, Patterns, and Computational Aesthetics

The AI systems have brought about unique types of randomness, pattern generation, and computational aesthetics that can be utilized as conceptual frameworks in the modern art practice. In contrast to the conventional notion of randomness: chance operations in Dada or Cagean indeterminacy Generative unpredictability generated by AI can be seen through the use of complex statistical models, nonlinear transformations and the sheer number of possibilities of the learned representations of AI. This presents outputs which waver between coherence and deviation and gives the artist the ability to investigate the edge of structure, error and emergence. The latent patterns in training data are frequently produced by AI it can expose biases, repetitions and tendencies which are concept rich in their own right. These patterns have the capacity to reveal the latent structures of visual culture, linguistic behavior or data archives of groups. Artists may apply these pattern of computation to critique regimes of classification, representation, and surveillance or draw images of the abstract dynamics of machine thoughts. The conflict that exists between emergent order and algorithmic noise turns into a conceptual instrument, which enables artworks to pre-empt the aesthetics of computation itself. AI-generated computational aesthetics are unlike other established artistic forms and styles in that they have their basis in statistical inference, and not gesture or intentional creation of form.

4. Artistic Precedents and Case Studies

4.1. Early algorithmic and computational art as conceptual foundations

The history of AI-driven conceptual art has its origins in the early algorithmic and computational art of the 1960s and 1970s which provided the critical precedents of viewing technological systems as meaning-making machines instead of a production means. Artists like Vera Molnár, Frieder Nake, and Manfred Mohr also explored the use of programmed instructions and mathematical logic to make artworks that predicted process, rule-based behavior and aesthetics of computation. These were the conceptual works, as the algorithm was the main artistic suggestion, instead of the completed visual representation. The piece of art was the implementation of a concept using a system and is quite akin to the conceptual approaches of highly conceptualizing contemporary art, focusing on dematerialization and the dominance of thought. These innovators proved that in a random way, permutation, and computational decision-making can be artistic tools that can create new aesthetics possibilities. Notably, they disclosed that machines are capable of being involved in creative procedures, despite having to work under strict guidelines. Their plotters, primitive computers and generative instructions formed a legacy of rule-based art and systemic art that would eventually be the foundation of conceptual frameworks of AI-based art.

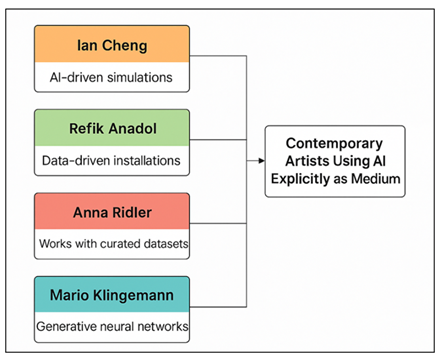

4.2. Contemporary Artists Using AI Explicitly as Medium

In the twenty-first century, there is a tendency of a further rise in artists who have embraced the use of artificial intelligence as not merely a tool of production but a medium of central concern, which influences the conceptual logic of the piece. These artists use AI in order to challenge the systems of knowledge, to explore what can be perceived by machines, and to challenge the notion of authorship and creative agency. Ian Cheng, Refik Anadol, Anna Ridler, and Mario Klingemann are among the most well-known artists who have employed neural networks, generative adversarial systems and big data to produce artworks whose meaning is formed through the workings of an algorithm. The live simulations offered by Ian Cheng, e.g. involve AI-controlled agents that create new narrative ecosystems with developing narratives, where characters act independently, casting doubt on the intentionality and lack of predictability. Figure 3 points out the AI-informed approaches to the modern-day conceptual art practices. The data-driven installations by Refik Anadol restructure the archival databases into the visual worlds, implying that data processing by machines may demonstrate patterns of group memory and perception.

Figure 3

Figure 3 AI-Driven

Artistic Methodologies in Contemporary Conceptual Art

Artists such as Ridler preempt the subjective quality of data gathering by means of meticulously edited datasets to reveal the impact of human choices on machine productions. Meanwhile, Klingemann welcomes the generative instability of neural networks with vulnerability to aesthetics of failure, mutation, and hallucination in machines.

4.3. Analysis of Select Artworks That Rely on AI for Conceptual Meaning

A number of modern art objects show us the potential of AI to be an engine of meaning, where its computational forms, training materials and the behaviors that it produces create a meaning. These texts are not based on the visual or textual output per se but on the conceptual implication of machine intelligence, autonomy and working of the system as a whole. To provide the examples, the Memories of Passersby I by Mario Klingemann makes use of neural networks to create continuously changing portraits. The meaning of the artwork is that it will always produce forms of a human shape and leaves one wondering about identity and the way a machine can be able to create a form which questions the depth of psychology without having to live. On the same note, Mosaic Virus by Anna Ridler is a project that trains a gAN using a hand-labeled dataset to visualize variations of tulips. The imaginative power of the work is due to the relationship between the data bias, economic speculation, and the historical narrative: the composition of data determines the generated AI output, which reveals the role of the artist in training the machine perception. The BOB by Ian Cheng is an example of an AI-based creature, which develops a system of beliefs due to the interaction with its audience. The meaning of the artwork is a result of the interdependence between the input of the audience, the evolution of the algorithm, and the unpredictability of machine learning.

5. Theoretical Implications

5.1. AI’s impact on notions of authorship and creative agency

The problem of artificial intelligence and its introduction into the artistic practice greatly upsets the traditional ideas of authorship and creative agency, which were some of the main pillars of artistic history discourse. In conceptual art, authorship has always been a conflictual zone, frequently disrupted by means of instructions, delegations or systems in which the role of the artist is reduced to minimum. The introduction of AI into the process of destabilization further compounds this destabilization by bringing in a generative agent, which does not only process information but also generates outputs that might be rather unexpected, complex, or even evidently intentional. This widens the concept of distributed authorship moving the human-human partnership to more of human-machine co-production. Here, the artist is no longer in the position of being the exclusive producer but rather a designer of environments, a manager of productions or an orchestrator of situations between information, algorithms and audiences. The AI systems have some form of computational agency as they are able to draw patterns, interpolate associations and create new content using probabilistic arguments. Though this agency cannot be compared to human creativity, it opposes the view that intention is supposed to be consciously possessed by a human subject in order to be relevant in an artwork.

5.2. AI as Collaborator, Performer, or System Within Conceptual Frameworks

The introduction of AI in conceptual art work practice leaves open to different interpretations of its ontological role in the piece of art, where it is alternatively seen as a collaborator, performer or systemic structure. As a collaborator, AI also brings generative, surprising, and algorithmic decisions into the conceptual direction of the work. The artist and the AI are a dialogic partnership in this kind of relational model, and each of them influences the contributions made by the other. This is in line with conceptual practices of privileging co-authorship and distributed creative practices. Alternatively, AI can be used as a performer, in which it carries out actions, carries out conclusions, or real-time creation. At this role AI is visible as an agent of the unfolding logic of the piece of artwork. This performative dimension has been illustrated through interactive installations, live generative environments and autonomous simulations as machine actions conceive both temporal and behavioral meaning. The art work turns into a platform of the algorithm workings, predictability of the procedure, emergent activity, and responsiveness of the system.

5.3. Philosophical Implications: Intelligence, Intention, and Interpretation

The conceptual art generated using AI provokes some urging philosophical questions concerning the essence of intelligence, where the intention was focused, and how the meaning is decoded. The implication of artificial intelligence is that human and nonhuman cognition have a complex relationship since it exhibits behaviors, including pattern recognition, generative synthesis, adaptive response, which can be viewed as a type of reasoning or creativity despite being based on entirely different mechanisms. This puts into perspective philosophical constructs that put intelligence solely at the conscious deliberation or experience. The question of intent comes into the same kind of trouble. The traditional aesthetics presuppose that art pieces reflect the will of their creators. However, AI-generated work can oftentimes be a result of calculations, which are not conscious of themselves, want what they have, or have any intention. This paradox makes it necessary to reconsider the fact that intention should be initiated by a sentient subject or it can be shared between systems, protocols and training data. This change is particularly fateful in conceptual art, where personal expression is sometimes secondary to conception: the will may be in how a system is designed, in the choice of inputs, in the very conceptual structure, instead of in a particular conscious entity. Interpretation also is more complicated.

6. Limitations and Challenges

6.1. Technological constraints influencing artistic outcomes

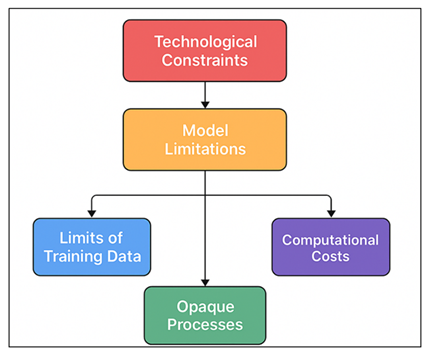

In spite of the fact that AI enables novel conceptual art, its application is conditioned by various technological limitations that determine the results of artistic activity to great extent. These shortcomings are pegged on the design of AI models, the character of training data, and the computational resources needed to be used in complex generative processes. Figure 4 provides the structural representation of the main technological constraints in AI-mediated art.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Structural Model of Technological

Limitations in AI-Mediated Art

Artists who deal with AI have to struggle with the reality that machine learning systems act within predefined variables: their results are conditioned by the structure of the dataset, the design of the model, and statistical assumptions of the algorithm. Consequently, the generative space is not neutral and infinitely open, but the aspect of it that is determined by the technological decisions and prejudices of the system. Another factor of artistic production is hardware limitations. Models of high-resolution generation or real-time simulation require intensive computing resources and are inaccessible to artists who lack institutional or other financial resources. Such technicity can affect the types of work created, favoring looks and forms based on the equipment, but not the aesthetics or the pure conceptuality. Moreover, the opacitance of modern AI systems, which can be characterized as black boxes, does not give the artist a full size of the internal processes, which can be controlled. It poses difficulty in transparency and deliberateness in conceptual frameworks that still hold clarity of method highly esteemed.

6.2. Overreliance on Model Outputs and Homogenization of Aesthetic Forms

The danger of too much dependence on model outputs is one of the evident threats of including AI into the process of conceptual art, as it might result in homogenization of the forms. Since the majority of artists use readily available pre-trained models, frequently created by giant companies, the results created are likely to follow common stylistic trends and visual/linguistic patterns. This may lead to a convergence of the vocabularies of aesthetics, reducing the variety of artistic expression, and supporting the biases and cultural assumptions underlying the model. The excessive dependence on AI-produced content could also result in the lack of artistic focus on the conceptual rigor and turn it into the novelty of the surface. When artists internalize model outputs, the artwork will become an act of exemplification of what the model is capable of doing, instead of being a critical or interrogative act involving the underlying logic behind it. The power of conceptual art is in the conscious organization of thought, over-reliance on machine productions can undermine this paradigm by replacing algorithmic hint with conscious conceptual inculcation. Homogenization also arises out of training data. A mainstream tastes and normative models are more likely to be reproduced when models are trained on big, culture hegemonic datasets. This creates a self-recycling cycle where the identical tropes of style come to be repeated throughout AI-generated products, restricting the possibility of originality and critical deviation.

6.3. Conceptual Risks: Novelty Fatigue and Technological Determinism

As AI finds its way into artistic practice, there are conceptual risks of AI, notably of fatigue of novelty and technological determinism. Novelty fatigue occurs when viewers and institutions become too obsessed by the technological spectacle of AI instead of the conceptual content of the work. In this instance, the very fact that AI is used can be seen to gloss over the concept behind the artwork to make it seem a display of computing power. This focus on technological newness, in the long-term, reduces the conceptual weight of AI-based art because as it is repeated, it becomes desensitized, and the critical engagement decreases. The same is risked by technological determinism. It is identified when the technology itself is assumed to drive the meaning of art, meaning that the ability of the medium determines the idea structure. This negatively impacts on the critical part of the artist in creating the intention and interpretation of the artwork. When AI is considered as a process of natural progress or a more advanced creative power, the tradition of skepticism and questioning of conceptual art is undermined. The painting might unintentionally support the ideology of technological determinism and ignore the sociopolitical consequences of AI systems, including data mining, business domination, and algorithmic bias. These dangers provoke the credibility of the intellectual project of conceptual art.

7. Conclusion

The introduction of artificial intelligence into modern conceptual art practice is more of an expansion and a dramatic shift of the basic tenets of the movement. Conceptual art has traditionally given more privilege to ideas, systems, and processes than to the materiality of the object, attempting to take the underlying structures of meaning production into view. AI builds upon this project by proposing a medium that can produce, read and convert linguistic, visual, and symbolic content in a manner that subverts the conventional view concerning the understanding of authorship, agency, and cognition. AI allows artists to venture into novel forms of speculation, bring the immaterial into physical form, and create elaborate relational structures that are beyond the faculties of human thought alone through its ability to identify patterns, generate synthesis, and operate on a system level. Simultaneously, AI exposes the circumstances in which modern technological systems are run, which provides a good platform to explore them critically. The fact that it uses training information, algorithmic structures, and institutional infrastructures place it in wider sociotechnical settings which may be interrogated, critiqued, or re-used by conceptual artists. AI is therefore not only a generative medium, but a subject of conceptual inquiry, furthering the field on which knowledge claims of intelligence, willfulness and meaning are argued.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Alotaibi, N. S. (2024). The Impact of AI and LMS Integration on the Future Of Higher Education: Opportunities, Challenges, and Strategies for Transformation. Sustainability, 16(23), 10357. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310357

Cao, Y., Li, S., Liu, Y., Yan, Z., Dai, Y., Yu, P. S., and Sun, L. (2023). A Comprehensive Survey of AI-Generated Content (AIGC): A History of Generative AI from GAN to ChatGPT. ArXiv Preprint Arxiv:2303.04226.

Chan, C. K. Y., and Lee, K. K. W. (2023). The AI Generation Gap: Are Gen Z Students More Interested in Adopting Generative AI such as ChatGPT in Teaching and Learning Than Their Gen X and Millennial Generation teachers? arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.02878. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-023-00269-3

Chiu, M. C., Hwang, G. J., Hsia, L. H., and Shyu, F. M. (2022). Artificial Intelligence-Supported Art Education: A Deep Learning-Based System for Promoting University Students’ Artwork Appreciation and Painting Outcomes. Interactive Learning Environments, 32(5), 824–842. Https://Doi.Org/10.1080/10494820.2022.2100426

Davidovitch, N., and Cohen, E. (2024). Administrative Roles in Academia—Potential Clash with Research Output and Teaching Quality? Cogent Education, 11, 2357914. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2024.2357914

Dehouche, N., and Dehouche, K. (2023). What’s in a Text-to-Image Prompt? The Potential of Stable Diffusion in Visual Arts Education. Heliyon, 9(8), e16757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16757

Ernesto, D., and Gerardou, F. S. (2023). Challenges and Opportunities of Generative AI for Higher Education as Explained by ChatGPT. Education Sciences, 13(9), 856. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090856

Hutson, J., and Lang, M. (2023). Content Creation or Interpolation: AI Generative Digital Art in the Classroom. Metaverse, 4(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.54517/m.v4i1.2158

Ivanov, S., and Soliman, M. (2023). Game of Algorithms: ChatGPT Implications for the Future of Tourism Education and Research. Journal of Tourism Futures, 9(2), 214–221. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-02-2023-0038

Kalniņa, D., Nīmante, D., and Baranova, S. (2024). Artificial Intelligence for Higher Education: Benefits and Challenges for Pre-Service Teachers. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1501819. Https://Doi.Org/10.3389/Feduc.2024.1501819

Lacey, M. M., and Smith, D. P. (2023). Teaching and Assessment of the Future Today: Higher Education and AI. Microbiology Australia, 44(3), 124–126. https://doi.org/10.1071/MA23036

Lim, W. M., Gunasekara, A., Pallant, J. L., Pallant, J. I., and Pechenkina, E. (2023). Generative AI and the Future of Education: Ragnarök or Reformation? A Paradoxical Perspective from Management Educators. International Journal of Management Education, 21, 100790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2023.100790

O’Dea, X. (2024). Generative AI: Is it a Paradigm Shift for Higher Education? Studies in Higher Education, 49(5), 811–816. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2024.2332944

Pataranutaporn, P., Danry, V., Leong, J., Punpongsanon, P., Novy, D., Maes, P., and Sra, M. (2021). AI-Generated Characters for Supporting Personalized Learning and Well-Being. Nature Machine Intelligence, 3(11), 1013–1022. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-021-00417-9

Sullivan, M., Kelly, A., and McLaughlan, P. (2023). ChatGPT in Higher Education: Considerations for Academic Integrity and Student Learning. Journal of Applied Learning and Teaching, 6(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.37074/jalt.2023.6.1.17

Walczak, K., and Cellary, W. (2023).

Challenges for Higher Education in the Era of Widespread Access to Generative

AI. Economics and Business Review, 9(2), 71–100. https://doi.org/10.18559/ebr.2023.2.743

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.