ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Smart Contracts for AI-Generated Art Rights

Dr. C. Komalavalli 1![]()

![]() ,

Rinki Bhati 2

,

Rinki Bhati 2![]() , Akhilesh Kumar Khan 3

, Akhilesh Kumar Khan 3![]() , Dr. Arun Kumar Tripathi 4

, Dr. Arun Kumar Tripathi 4![]()

![]() ,

Arpit Arora 5

,

Arpit Arora 5![]()

![]() ,

Gunveen Ahluwalia 6

,

Gunveen Ahluwalia 6![]()

![]() ,

Kajal Sanjay Diwate 7

,

Kajal Sanjay Diwate 7![]()

1 Professor,

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Presidency University,

Bangalore, Karnataka, India

2 Associate

Professor, Department of English, Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli,

Tamil Nadu, India

3 Greater

Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201306, India

4 Professor,

Department of Computer Science, Noida Institute of Engineering and Technology,

Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

5 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

6 Chitkara

Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University, Himachal Pradesh,

Solan 174103, India

7 Department

of Artificial Intelligence and Data Science, Vishwakarma Institute of

Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The swift

AI-generated art development has further fueled the discussion on both

authorship and ownership, as well as on whether digital rights can be

enforced. The existing intellectual property paradigms lack the ability to

recognise works produced by autonomous systems fully or in part, which

presents proxies in the maintenance of copyright, derivatives and

cross-jurisdictional identification of AI-related rights. With more and more

creative outputs based on algorithmic processes, there is an urgent requirement

to have transparent, tamper-resistant processes that would be able to define,

assign and protect right at scale. One of the promising infrastructures to

facilitate legal and economic aspects of AI-generated art is the use of smart

contracts, which are the self-executable agreements that run on blockchain

networks. This paper discusses how authorship claims can be encoded in smart

contracts, how royalty payments can be automated, and how programmable access

controls can be offered, at the same time, offering verifiable provenance by

tokenizing the provenance. We analyze technical specifications of creating

powerful metadata standards to cover creation parameters, level of

contributions, and model lineage. Moreover, we discuss interoperability

issues in the heterogeneous blockchains and digital marketplaces, which are

limited to the immutability, upgradability, and long-term security. In

addition to the technical design, the paper evaluates the ethical impact,

such as the fairness to human designers, responsible design of AI innovators,

and risks to society in general of bias, exploitation, and its unequal

distribution of rights-management systems. |

|||

|

Received 25 February 2025 Accepted 23 June 2025 Published 20 December 2025 Corresponding Author Dr. C.

Komalavalli, komalavalli.c@presidencyuniversity.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i3s.2025.6803 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: AI-Generated Art, Smart Contracts, Digital Rights

Management, Blockchain Provenance, Copyright and Authorship, Tokenization |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

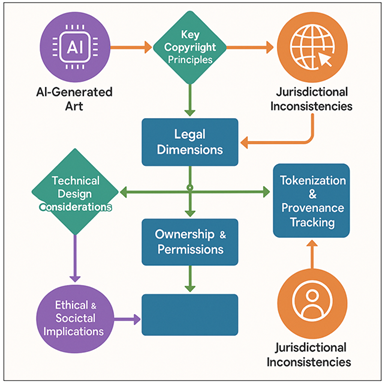

The development of artificial intelligence has quickly changed the environment of creative production, and it has sparked enthusiasm and concern in artistic, legal, and technological circles. Machine-learning systems that have the ability to create images, music, literature and multimedia works pose a threat to traditional notions of creativity, authorship and intellectual property. Generative adversarial network (GAN)-based tools, diffusion-based architectures, and large-scale transformer architectures have enabled people with minimal technical expertise to create complex works of art that can compete with that of a professional. With such systems being more and more open and more and more autonomous, the boundaries between human creativity and algorithmic generation become indistinct and some of the most fundamental questions emerge regarding how these works are supposed to be controlled, attributed, and monetized in the modern digital ecosystems. The AI generated art presents new complexities in the management of rights Rathore et al. (2021). Classical copyright law is based on the assumption of a human author-conditioned requirement which is not consistent with the autonomous computational creativity of many types. In some regions that insist that manuscripts need to be authored by individuals to be eligible to be covered by copyright laws, the works produced by AI can usually find themselves in the legal grey areas, with creators, developers, and platforms unable to understand what they own or what can be used as derivatives. Other jurisdictions have already started to experiment with more liberal interpretations, meanwhile, without any international consensus having arisen Zeid et al. (2019). This makes the artist, collectors, and commercial entities that cross border so much more difficult since there is no legal uniformity, especially in the digital art markets where transactions often cut across jurisdictions. The Figure 1 illustrates the process of tokenizing AI art, where smart contracts are used to automate the ownership validation process, to enforce the right to usage, and to ensure transparent digital transactions. It is against this context of legal ambiguity that blockchain-based smart contracts are a potential breakthrough.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Process Flow of AI Art Tokenization and Rights Enforcement through Smart Contracts

Self-executable written in code and implemented in decentralized networks, smart contracts can store conventions of authorship claims, royalty payments, licensing policies, and permissions to use it. Their automation, transparency, and immutability make them appealing instruments in the management of the ever-complicated rights situation that the art generated by AI is about to face. Although it is a promising approach, the incorporation of smart contracts into the AI art ecosystems is not as simple as it sounds Bello and Zeadally (2019). There are still technical questions about the most effective way to store the authorship metadata, how to make it interoperable with other blockchains and art marketplaces and how to compromise the immutability with the necessity to revise the rights information in accordance with the changes of legal standards.

2. Background Work

The development of AI-generated art is based on multiple decades of study in the field of computational creativity, digital rights management and blockchain-based governance. They were theoretically and technologically pre-empted by the work of early algorithmic art in the 1960s and 1970s as pioneered by writers like Harold Cohen and Frieder Nake. They were rule-based and deterministic systems; this contrasts with modern, data-driven and probabilistic systems Kiani and Sheng (2024). The development of machine learning, especially neural networks in the 1990s and deep learning in the 2010s, made it possible to learn complex visual and stylistic patterns on large data volumes, and the breakthrough methods that include GANs and variational autoencoders and, most recently, diffusion-based generators of images have emerged. Such inventions broadened the artistic approaches and cast new doubts on the originality, training statistics as well as authorship. Concurrent with the rise of AI as a creative medium, researchers and computer technology experts have explored how conventional copyright models fail when used in relation to the creation of works with few or no direct human interaction Nguyen et al. (2024). Conspicuous researches have stressed that it is not an easy task to apply human-oriented authorship theories to machine-generated products with references to discordances between the creative activity and the governing legal framework focusing on intent, creativity, and ownership. Digital rights management (DRM) research has also provided some background information, illustrating what can and can not be done to implement the anything in the digital world by computational means to enforce licensing terms and ownership tracking Chatterjee and Ramamurthy (2024). New advancements came with blockchain technologies, especially with decentralized registries that are able to establish a track of transparent, immutable histories of digital assets. NFTs have rekindled attention towards provenance tracking, which has created the potential of verifiable ownership and programmable royalties. Smart contracts are a topic of academic interest, and have been proposed in the context of decentralized finance, decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs), and supply chain tracing as a technical blueprint of automating agreements, complex rights structures, and eliminating reliance on intermediaries Zhao et al. (2024). Table 1 is a summary of the research on the field of AI art generation and rights management through smart contracts. The new interdisciplinary practice has already started to combine these strands, asking about how AI-generated content can be controlled using tools based on blockchain.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Related Work on AI-Generated Art and Smart Contract Rights Management |

||||

|

Title / Study Focus |

Domain |

Key Contribution |

Technology |

Limitations |

|

AARON: The Early Algorithmic

Artist |

Computational Creativity |

Introduced rule-based art

generation |

Procedural Algorithms |

Limited autonomy |

|

Generative Adversarial

Networks Khoramnejad and Hossain (2024) |

Machine Learning |

Proposed GAN framework for

image synthesis |

Neural Networks |

High compute cost |

|

Sale of AI-Generated

Portrait |

Art Market |

First AI artwork auctioned |

GAN + Blockchain Provenance |

Lacked clear rights

attribution |

|

Creative AI and Authorship Epstein et al. (2023) |

AI Ethics |

Discussed authorship in

machine creativity |

Theoretical Framework |

No technical implementation |

|

AI Authorship Rejection Case |

Copyright Law |

Tested AI’s eligibility for

copyright |

Legal Ruling |

U.S.-specific interpretation |

|

NFT Marketplace Development Brynjolfsson et al. (2023) |

Blockchain Commerce |

Enabled tokenized art sales |

Smart Contracts (ERC-721) |

Centralized elements |

|

NFT Royalty Standardization |

Token Protocol |

Automated royalty

distribution |

Ethereum Smart Contracts |

Partial adoption |

|

AI Ethics Recommendation Choie et al. (2025) |

Global Policy |

Advocated ethical governance

of AI |

Policy Framework |

Non-binding principles |

|

AI and IP Policy Challenges |

Legal Governance |

Explored global IP

implications |

Comparative Law Analysis |

Lacks enforcement mechanisms |

|

Decentralized Storage

Protocols |

Blockchain Infrastructure |

Ensured immutability of art

files |

Distributed Ledger |

Metadata fragility |

|

Stable Diffusion / DALL·E 2 Prathigadapa and Daud (2025) |

Generative AI |

Enabled high-quality image

generation |

Transformer and Diffusion

Networks |

Ambiguous data sources |

|

Community-Led Ownership

Models Bellini and Bignami (2025) |

Decentralized Systems |

Explored collective

authorship models |

Smart Contracts + Token

Voting |

Low user literacy |

|

Blockchain DRM Frameworks |

Digital Rights Management |

Proposed blockchain for IP

enforcement |

Hybrid On-/Off-Chain Model |

Scalability limits |

|

Smart Contracts for

AI-Generated Art Rights Gardazi et al. (2025) |

Interdisciplinary |

Integrates legal, technical,

and ethical dimensions |

Smart Contracts + Metadata

Standards |

Regulatory uncertainty |

3. Legal Dimensions of AI-Generated Art

3.1. Outline key copyright principles and their ambiguity with AI-created works.

The copyright law has been based on a number of principles that have been considered to be original, fixed, and human authored and all of them become unclear when it comes to the AI produced art. The originality criterion means that a human author has used skill, judgment or creative decisions but most of the present AI systems are made autonomously based on statistical patterns of training data. This poses the question of whether products that come out without any deliberate creative intention of the human can be considered the work of authorship. Equally, fixation, the need to have the work fixed in a physical form, is also usually fulfilled in digital forms, but the question remains, who does this fixing of the work happen when an algorithm brings about the generation Matarazzo and Torlone (2025). The greatest lack of clarity is the question of authorship. Generative systems do not presuppose identifiable creative expression by any single person, as copyright regimes have always assumed. Individuals who provide prompts, those who implement algorithms and those who provide training corpora by curating the dataset all play a part in the ultimate output, yet the law does not provide any explicit guidelines as to who should be credited with authorship Lai et al. (2024). Besides, the outputs of AI tend to be stylistically influenced or recognizable based on training data, thus whether such pieces are infringing or unauthorized derivative works.

3.2. Authorship, Ownership, and Derivative Rights Disputes

The issue of authorship in AI-generated art is often between establishing who the creative input was and who was of good standing to receive legal protection. Prompt providers believe that their contribution to the final aesthetics is significant, whereas developers assume that the architecture and training of the model constitute the most significant creative gesture that makes generation possible. Creative influence could also be claimed by dataset curators whose collection determines the stylistic results. However, there is no common or distributed authorship across these crossed roles in existing laws, which consequently results in fragmented or undetermined ownership. The ambiguity of contractual conditions along with the usage of AI tools is the most common source of ownership disputes. Social networks frequently provide users with wide rights of use but at the same time, limit property or resale of the content created. Others of the services renounce all rights and the outputs are in the public domain whereas others claim to own their platform. Such discrepancies result in controversies as works of art acquire commercial significances or are assembled as part of a bigger body of creative works. Moreover, the human-AI workflows create challenges around the concepts of co-authorship, in which both parties have a significant influence on the end product. The point of disagreement in derivative rights is rooted in the fact that with the aid of AI, there is a chance that the generated outputs will replicate or be highly similar to the works of copyright in the training sets.

3.3. Jurisdictional Inconsistencies in AI Rights Recognition

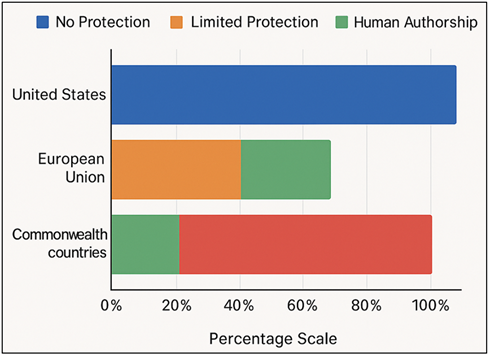

The legal framework on the treatment of AI-generated works is highly fragmented with global copyright systems treating the issue in different ways. The Copyright Office in the United States supports the position that only man-made works can be put under protection and specifically opposes the registration of outputs produced by AI-autonomous algorithms. The human contribution should be significant and imaginatively relevant, but the boundary is not defined, and creators have no idea whether timely engineering or model setup can be considered. In contrast, the United Kingdom and a number of Commonwealth jurisdictions have limited protection on the works of a computer-generated nature, with authorship being considered to the person who makes the so-called arrangements required to make the work. This is a bit enlightening but has been condemned as out of date and not enough driven to modern machine learning. Within the changing regulatory landscape of the European Union, there is still controversy on whether the output of AI is to be safeguarded, and whom to safeguard it using what category of law. There are those member states that focus on human authorship and others that are not closed to sui generis rights or hybrid protection mechanisms. At the same time East Asian countries have started to experiment with more liberal interpretations. As an example, jurisdictions may have allowed AI-generated materials to have limited rights when the input of human input is deemed relevant, and the standards are most diverse. The jurisdictional differences in regards to recognition and protection of AI-related rights are compared in Figure 2. These inconsistencies prevent the cross-border usage, distribution, and commercialization of AI-generated art.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Comparative Analysis of Jurisdictional Inconsistencies in AI Rights Recognition

International market places are caught up in contradictory regulations on ownership, licensing, and infringement.

4. Smart Contracts as a Rights Management Mechanism

4.1. Explain smart contract architecture and automated rule enforcement.

Smart contracts are computer-executed digital contracts that are coded on blockchain networks and they are intended to be free of central intermediaries. They are based on sequencing programmable conditions and actions which are loaded into distributed ledgers so that when specified criteria are followed, the contract automatically fulfils its terms. Smart contracts usually consist of functions defining ownership, revenue division, user access restrictions, and transaction execution when a user interacts with the smart contract or outside data is received. Since they operate with decentralized infrastructure, the implementation of these agreements is transparent, resistant to interference, and can be verified by all parties, thus eliminating the possibility of conflicts or ungrounded interference. Smart contracts are also a form of governance in the environment of AI-generated art as they can formalize the rights and responsibilities of the contributors, platform operators, and collectors. They may be coded in such a way that they verify the source of a piece of artwork, ensure the integrity of metadata, and limit transfers or access based on a set of established licensing policies. Rule enforcement: Automated rule enforcement provides consistency in the implementation of conditions, including a royalty payment, or restriction of use or resale of the item to be used. An example is that with a given resale of an AI-generated artwork, automatic proportional royalty payments can be made to specified creators or rights holders.

4.2. Tokenization and Provenance Tracking for AI Art

The tokenization of AI-created artworks represents a digital art piece in the form of a distinct or semi-fungible asset which can be represented, traded, and authenticated on blockchain networks. The most widespread one is the issuance of non-fungible tokens (NFTs) connecting the artwork and a cryptographically sealed on-chain address. This marker refers to the metadata behind the piece itself, which can contain the model that generated it, creation parameters, the prompts, who created it, when it was created and version details. The tokenization of the artwork by adding this information at the time of minting creates a verifiable, immutable provenance chain that records the provenance of the artwork and its history. The provenance tracking is a valuable element in AI-based art systems where the identity of authorship and authenticity is not straightforward. The distributed registry of blockchain all the transactions, transfers, changes, and so on producing a clear trail that can be accessed by collectors, markets, and legal regulators.

4.3. Models for Assigning Ownership, Royalties, and Usage Permissions

To ensure a proper rights management of AI-generated art, there is a need to have models that explain the ownership, automate flows of royalty and establish use permissions in transparent, enforceable terms. By use of smart contracts, there are various ownership forms that are possible. One of them attributes the main ownership to the person who triggers the generative process- usually the user who makes the prompts or design parameters. The other model assigns ownership to the developer or entity that has the AI system being constructed where output is considered a derivative product of the model architecture.

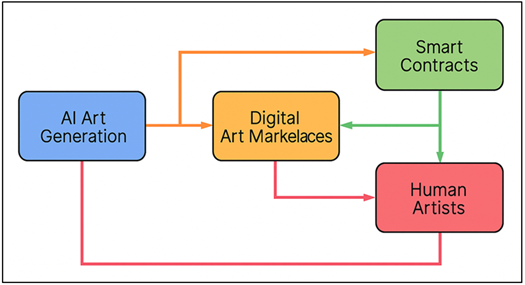

Figure 3

Figure 3 Smart Contract Package Diagram for AI-Generated Art Rights Management

Fractional ownership is distributed in hybrid models between contributors, such as prompt designers, AI developers as well as dataset curators, and generative workflows are collaborative. Royalty management is a fundamental aspect of smart contracts, which enables creators to get automated payments on the primary and secondary sale, which are perpetual. Figure 3 presents the elements of smart contracts that control the rights of AI-created art. Depending on the usage trends, contribution rates or joint working conditions, royalty percentages are hard-coded or can vary dynamically. Multi-recipient royalty splits facilitate precision bi-compensation systems in which multiple rights holder are automatically compensated on each usage, which not only lightens the administrative load, but also allows justice in distributed creative systems. Smart contracts can also have usage permissions embedded in them. These licenses can limit commercial abuses, regulate the right of display, regulate reproduction, or even define the right ofderivative work. The programmable licensing structures can include tiered licensing frameworks or time-based licensing frameworks that enable the collectors and the platforms to communicate with the artwork in the framework of predetermined conditions that are monitored and enforced automatically with code.

5. Technical Design Considerations

5.1. Define metadata standards for recording authorship and creation parameters.

It is essential to build strong metadata standards that will represent the authorship, creation parameters, and lineage in the case of AI-generated art to document it properly. Metadata is the foundation of any rights-management system, granting that each work of art is put into verifiable contexts of its sources and the efforts that creators or systems make to it. An extended metadata scheme of AI art must cover the information regarding the generating model, e.g. model version, the type of training dataset, the architecture of the algorithm used, and any fine-tuning steps applied. Also, human creative role should be captured by capturing user inputs such as prompts, parameter adjustments, seed values or iterative optimizations. Fields of authorship have to vary between different contributors such as prompt engineers, model developers, dataset curators, and platform operators. Such a stratified system allows more transparent attribution and allows any flexible ownership or royalty distribution model. The other necessary piece is timestamping, which offers the records of the time of the generation that cannot be modified, the time of minting the token, and the time of any modifications or licensing alterations. To maximize compatibility between platforms, metadata needs to follow standardized formats, E.g. JSON-LD or extended ERC token metadata schema.

5.2. Interoperability Across Blockchains and Art Marketplaces

Interoperability has to be discovered in order that AI-generated artworks would flow freely across various blockchains, marketplaces and digital ecosystems. Since the creative assets can be created or discovered on one network and then traded or shown on others, technical ships need to make sure that ownership and provenance metadata and rights metadata are not lost in the transfer. Cross-chain interoperability is usually based on token bridges or wrapped asset protocols, interoperability standards like Inter-Blockchain Communication (IBC) and cross-chain messaging frameworks. Through these protocols, assets can be moved/mirrored among blockchains and still be guaranteed cryptographically as authentic. Marketplace interoperability involves the following: compliance with common metadata standards, royalty-distribution protocols and licensing schemas. In the absence of harmonized frameworks the artists and collectors experience incongruencies in the way the rights are perceived or implemented on the platforms. ERC-721C, ERC-2981 standards on royalties and the developing extensions of multi-chain metadata standards can decrease fragmentation. Also, decentralized storage like IPFS or Arweave will help to make sure that files containing artwork off-chain are still accessible, and untampered throughout the environment, even when ownership of the token is transferred to other networks.

5.3. Security, Immutability, and Update Constraints

The issue of security and immutability, as well as restricting updates, will be paramount when developing technical structures of AI-generated art. Blockchain is immutable and when metadata, ownership information, or the terms of a license are stored, these entries will never be changed unless network participants agree to do so, which guarantees high resistance to tampering or other unauthorized changes. Nonetheless, this immutability also puts in place limitations particularly when the law frameworks or amended metadata need to be revised. To cope with this, designers frequently adopt hybrid-architectures in which mutable elements are off-chain, but important hashes or signatures are stored on-chain so that they can permit controlled revisions without affecting provenance integrity. The security concerns due to the potential attack vectors include metadata manipulation, malicious token contract, compromised private keys, or token bridge vulnerabilities. Smart contracts should be highly audited to eliminate exploits that may manipulate royalty structures, payments, and spoof ownership documents. The multi-signature control, timelocks, and permissioned update functions can be used to reduce the risk without making it less flexible to operations.

6. Ethical and Societal Implications

6.1. Consider fairness toward human artists versus AI model developers.

The example of incorporating AI into art is provoking urgent questions regarding ethical equality between humans and the developers of AI models. Human artists claim that generative tools tend to imitate their unique style or redefine art patterns without their permission, which reflects the years of work and self-expression. Most AI systems are trained using datasets of copyrighted artworks, often obtained by crawling without permission, which causes them to produce content that replicates or combines the style of a human being without compensation. This dynamism endangers the established concept of artistic integrity, authorship and livelihood. On the other hand, developers and data scientists believe that they are creative in their approach to automating creativity, which is achieved through the development of algorithms, training data pipelines, and computing structures. In this light, the creative process does not change directly to its technical support, but it is the creative process that is converted into an algorithmic authorship. Nevertheless, the potential disadvantage of giving priority to developer ownership is that it will overshadow human creativity and entrench power structures in favor of large tech firms that can afford to train complicated models. Fairness therefore requires a form of doing justice between the contributions of the two groups. Solutions based on smart contracting and equitable royalty distribution can be encoded in the policy framework to ensure that the developers and human artists are proportionately rewarded and compensated.

6.2. Risks of Bias, Exploitation, and Unequal Access to Smart Contract Systems

Although smart contracts are expected to be more transparent and automate the process of handling AI-generated art rights, they might also cause the system to perpetuate existing inequities and create new ways of digital exploitation. Blockchain technology, crypto markets, and technical literacy access is not evenly distributed by region and demographics, and may lock out marginalized artists in the participation of decentralized art economies. The economic and computational expenses of implementing smart contracts, e.g., gas charges or multifaceted wallet management, are likely to reduce the interest of small-scale creators but advantage institutional participants and professionally-funded developers. The risk of bias in AI models also increases ethical threats. In case the training data displays the societal stereotypes or lacks representation of some cultural manifestation, the artworks will support the discriminatory norms and uphold the dominant aesthetic paradigms. In addition, the nature of smart contracts themselves may be structured biased when authored without any input, in the form of unjust royalty allocations, restrictive terms of use, or black-box licensing bureaucracies.

6.3. Economic Impacts on Digital Art Ecosystems

The emergence of AI-generated art and blockchain-managed rights usage are transforming the digital art economy on the global front. On the one hand, automation and tokenization lead to the widening of opportunities of artists as they democratize the access to tools, allow direct-to-market sales, and new forms of interaction between a human and a machine. Smart contracts make it possible to do micro-transactions and royalty-perpetual, which enables creators who are not always included in the current art markets to have sustainable revenue streams. Ultimately, there are economic-impact architecture that translates AI-driven digital art ecosystems (described in Figure 4). The tools of AI also facilitate faster creativeness and reduce the entry barriers and promote experimentation.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Architecture of Economic Impacts in AI-Driven

Digital Art Ecosystems

Nevertheless, the same technologies break the value hierarchies that are present in art ecosystems. The flood of AI-created content may saturate the digital market at the expense of originality and human artists may struggle to stand out in the crowd of the algorithmically generated content. It is possible that collectors have a difficult time in determining authenticity or aesthetic worth of art when it can be reproduced indefinitely with little human intervention. Moreover, capital accumulation is likely to be concentrated with operators of platforms, NFT markets, and AI developers, but not with individual creators, as with the Web2 economies of centralized pretenses. Volatility in crypto markets also increases the problem of sustainability. Long-term stability will be compromised by price speculation and token inflation as well as environmental concerns associated with energy-intensive blockchains.

7. Conclusion

Artificial intelligence and blockchain technology merging are transforming the limits of the creative ownership, legal responsibility, and financial involvement in the digital art ecosystems. Traditional paradigms of copyright and authorship fail to keep up with algorithmic creativity as AI systems produce more and more sophisticated and original works of art. The ambiguities that come as a result, including how one determines who is the author, how the rights are shared and in what circumstances the rights can be applied, require some novel mechanisms that should work both legally and technically accurately. Such mechanisms can be described as a good premise of smart contracts. They offer a visible, resistant infrastructure of authoritative control, with self-executing code, to manage the claims of authorship, automate the stream of royalty and track the provenance of an item, the history of which cannot be altered. Smart contracts can resolve the problem between fragmented legal frameworks and decentralized technological systems through the combination of metadata standards, tokenization frameworks, and interoperability protocols. These tools however are not without limitations. The problem of discrepancy in regulations, scalability, authoring of AI, and the possibility of manipulating the metadata remain challenges that have complicated the application of AI in practice. In addition to technical and legal aspects of AI-generated art, there are the ethical and societal aspects of this art that require the same attention.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Bellini, V., and Bignami, E. G. (2025). Generative Pre-Trained Transformer 4 (GPT-4) in Clinical Settings. The Lancet Digital Health, 7(1), e6–e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landig.2024.12.002

Bello, O., and Zeadally, S. (2019). Toward Efficient Smartification of the Internet of Things (IoT) Services. Future Generation Computer Systems, 92, 663–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2017.09.083

Brynjolfsson, E., Li, D., and Raymond, L. R. (2023). Generative AI at Work (NBER Working Paper No. 31161). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w31161

Chatterjee, S., and Ramamurthy, B. (2024). Efficacy of Various Large Language Models in Generating Smart Contracts. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-85363-0_31

Choi, B. K., Sohn, D. H., and Hong, J. (2025). Analysis and Comparison of PPP ZTD Using Empirical Models GPT, GPT-2, and GPT-3. Journal of Positioning, Navigation, and Timing, 14, 21–28.

Epstein, Z., Hertzmann, A., Akten, M., Farid, H., Fjeld, J., Frank, M. R., Groh, M., Herman, L., Leach, N., and Investigators of Human Creativity. (2023). Art and the Science of Generative AI. Science, 380(6650), 1110–1111. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adh4451

Gardazi, N. M., Daud, A., Malik, M. K., Bukhari, A., Alsahfi, T., and Alshemaimri, B. (2025). BERT Applications in Natural Language Processing: A Review. Artificial Intelligence Review, 58, Article 166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-025-11162-5

Khoramnejad, F., and Hossain, E. (2024). Generative AI for the Optimization of Next-Generation Wireless Networks: Basics, State-of-the-Art, and Open Challenges. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2025.3535554

Kiani, R., and Sheng, V. S. (2024). Ethereum Smart Contract Vulnerability Detection and Machine Learning-Driven Solutions: A Systematic Literature Review. Electronics, 13(12), Article 2295. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13122295

Lai, Z., Wu, T., Fei, X., and Ling, Q. (2024). BERT4ST: Fine-Tuning Pre-Trained Large Language Model for wind Power Forecasting. Energy Conversion and Management, 307, Article 118331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2024.118331

Matarazzo, A., and Torlone, R. (2025). A Survey on Large Language Models with Some Insights on their Capabilities and Limitations. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.04040

Nguyen, C. T., Liu, Y., Du, H., Hoang, D. T., Niyato, D., Nguyen, D. N., and Mao, S. (2024). Generative AI-Enabled Blockchain Networks: Fundamentals, Applications, and Case Study. IEEE Network, 39(2), 232–241. https://doi.org/10.1109/MNET.2024.3412161

Prathigadapa, S., and Daud, S. B. M. (2025). A Review of Virtual Tutoring Systems and Student Performance Analysis Using GPT-3. Journal of Learning for Development, 12(1), 168–181. https://doi.org/10.56059/jl4d.v12i1.1367

Rathore, M. M., Shah, S. A., Awad, A., Shukla, D., Vimal, S., and Paul, A. (2021). A Cyber-Physical System and Graph-Based Approach for Transportation Management in Smart Cities. Sustainability, 13(14), Article 7606. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147606

Zeid, A., Sundaram, S., Moghaddam, M., Kamarthi, S., and Marion, T. (2019). Interoperability in Smart Manufacturing: Research Challenges. Machines, 7(2), Article 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines7020021

Zhao, J., Chen, X., Yang, G., and Shen, Y. (2024). Automatic Smart Contract Comment Generation via Large Language Models and In-Context Learning. Information and Software Technology, 168, Article 107405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2024.107405

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.