ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Visual Semantics of AI-Generated Paintings

Gaurav Chaudhary 1![]() , Dr. Arvind Kumar Pandey 2

, Dr. Arvind Kumar Pandey 2![]()

![]() ,

Lakshya Swarup 3

,

Lakshya Swarup 3![]()

![]() ,

Sangeet Saroha 4

,

Sangeet Saroha 4![]() , Dr. Harsha Gupta 5

, Dr. Harsha Gupta 5![]()

![]() ,

Vibhor Mahajan 6

,

Vibhor Mahajan 6![]()

![]() ,

Sandhya Damodar Pandao 7

,

Sandhya Damodar Pandao 7![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, School of Sciences, Noida International University, India

2 Associate

Professor, Department of Computer Science and IT, Arka Jain University,

Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, India

3 Chitkara

Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University, Himachal Pradesh,

Solan 174103, India

4 Greater

Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201306, India

5 Assistant

Professor, Department of Information Technology, Noida Institute of Engineering

and Technology, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

6 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

7 Department

of Artificial Intelligence and Data Science, Vishwakarma Institute of

Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

This paper

examines the visual semantics of AI generated paintings focusing on the

crossroads between the computational creativity and the aesthetic

interpretation of paintings by humans. With the rise of artificial

intelligence based on powerful image-generation models, including Generative

Adversarial Networks (GANs) and diffusion models, the ability of machines to

generate image-based artworks with visual complexity and symbolic richness

has increased. Nonetheless, it is a question to whether these visual products

contain actual semantic depth or they only imitate human artistic intent. The

study is based on a mixed-method design that involves a combination of both

computational image analysis and qualitative semantic interpretation in order

to explore the construction and perception of meaning within AI-generated

art. The results of analysis of a curated dataset of AI-generated paintings

were presented using CLIP, DALL•E, and Midjourney to obtain visual features

and project them on conceptual and emotional planes. By applying the

conceptual theories of semiotics and aesthetics, the paper determines the

trends in color, composition and symbolism that are used to encode cultural

and perceptual information in AI models. It has been found that though AI

systems are able to adopt a human-like semantics via visual correlations

learned by training, their results are essentially derivational: based on

training data and probability associations as opposed to capturing original

creative intent. The discourse explains the ways AI-generated paintings

question traditional limits of authorship and artistic meaning in that they

propose a new paradigm, in which human users collaborate to create semantics

out of algorithmic aesthetics. |

|||

|

Received 22 February 2025 Accepted 21 June 2025 Published 20 December 2025 Corresponding Author Gaurav

Chaudhary, gaurav.chaudhary@niu.edu.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i3s.2025.6801 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: AI-Generated Art, Visual Semantics, Diffusion

Models, Computational Aesthetics, Machine Creativity |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

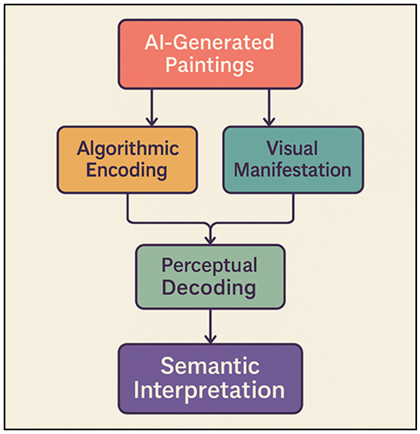

With the introduction of artificial intelligence (AI) in art, a new understanding of the interaction between technology, creativity, and human perception has been established. The artistic expression which was once regarded as a unique human realm is now being approached with the practice of algorithmic procedures that can create complex, emotive, and aesthetically engaging images. The advent of AI models like Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), and as of recently diffusion-based models like DALL•E, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion have all brought about a transitional period of visual culture wherein machines are not merely instruments for creating visual art but are also directly involved in the meaning-making process. The most important question to ask in this shift of paradigm is Can AI-generated images be said to have visual semantics or are they merely mimetic replications of human creativity? Visual semantics is a notion that is at the border of perception, symbolism, and interpretation. In conventional art, the visual semantics is the connection between visual content and signification, the mechanism by which images convey concepts, feelings or stories beyond their visual expression Rajpurkar et al. (2022). The application of the concept of visual semantics to AI-generated art makes it a complicated interaction between algorithmic procedures and the human interpretation. The meaning of AI models is not perceived consciously, but instead it is deduced based on large quantities of human-generated images and texts through the identification of patterns and correlations between these datasets. This brings up philosophical and aesthetic issues of authorship, intentionality and ontology of art in the digital era Rao et al. (2025). Do the machine-generated images contain information or are they just the reflection of human prejudices that are coded in the data? The introduction of AI in the art world has also caused a serious debate between artists, theorists and technologists. It is shown in Figure 1 that visual semantics in AI-generated paintings follow a conceptual flow. On the one hand, some find AI to be a groundbreaking instrument that increases the range of possibilities of artistic exploration; on the other hand, some find it as a threat to authenticity and creative ownership.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Conceptual Flowchart of Visual Semantics in

AI-Generated Paintings

However, in addition to these polarities, there is an impressive landscape of analyzing the functioning of AI-generated paintings as semiotic systems. The symbolic cues of each of the generated images, namely, the abstract, the surreal, and the representational ones, can be understood in a certain cultural and emotional setting. AI art pieces utilize color, form, composition and texture to invite viewers to meaning construction acts like those of the traditional art, albeit by other production processes Rajpurkar and Lungren (2023). Visual semantics in the pictures generated by the AI are, thus, not only a technical question, but also a philosophical question. It makes one think about the way in which meaning gets encoded and decoded in the visual media when the author is an algorithm.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Overview of AI-based image generation models

The advancement of AI-driven image generation has been facilitated mainly by the creation of the deep learning architecture that can produce the most detailed and realistic visual output. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) are another network, introduced by Goodfellow et al. (2014) that can be considered one of the greatest achievements in generative modeling. At the same time, GANs are based on a dual-network architecture that is comprised of a generator and a discriminator that are involved in adversarial training the generator generates images, whereas the discriminator judges their genuineness Hartmann et al. (2025). With time, improved versions like StyleGAN and BigGAN were developed, and they were better at controlling features such as texture, lighting, and composition and thus became potent tools in creative uses. More recently, diffusion models have been used to radically transform image synthesis by using probabilistic denoising generative algorithms, which progressively convert random noise to coherent images. DALL-E, Stable Diffusion, and Midjourney are models based on multimodal datasets and transformers trained on large-scale visual representations Quan et al. (2023). Diffusion models generate less artifacts and more semantically aligned results than GANs and achieve greater interpretability. They have the characteristic of these models being the transition of low-level pixel manipulation to semantic-level generation, where text or conceptual input is directly employed in visual composition. Consequently, AI-generated art ceases to be seen as a technical experiment to become conceptual art representing data-driven aesthetics Papia et al. (2023). This technological advancement supports the modern discourses of authorship, creativity, and the place of algorithms in visuality.

2.2. Theoretical Foundations of Visual Semantics

Visual semantics is a paradigm that intersects between cognitive psychology, semiotics and art theory, and deals with the question of how images are used to mean something other than what is inherent in their formal characteristics. Visual semantics is based on semiotic theories by theorists such as Ferdinand de Saussure, Charles Sanders Peirce and Roland Barthes, and studies the connection between the signifier (form drawn in a visual medium) and the signified (conceptual meaning) Ostmeyer et al. (2024). In the framework of art, such a relationship is a summation of how visual elements, color, line, shape, texture and composition, act as sign system, communicating emotions, narrative and ideologies. These semantic dynamics are given a new meaning in AI-generated imagery. With algorithms being consciousless and intentless, meaning is not created through conscious expression, but rather learned in the form of associations within training data sets Engel-Hermann and Skulmowski (2025). Digital aesthetics scholars claim that the visual semantics of AI art is a reflective process, that is connected to human cultural patterns, and not a source of new symbolism. Such images have their cognitive interpretation, thus, dependent much on human perception that imposes the semantic depth onto the constructed visuals using algorithmic processes Moshel et al. (2022).

2.3. Previous Studies on Human vs. AI Artistic Expression

Human and AI artistic expression are compared, with the stress on both similarities and dissimilarities of creativity, intentional, and meaning-making. Initial studies highlighted that human artists work using personal intuition, social environment and emotional meaning whereas AI systems are based on statistical associations and pattern recognition. As an example, Elgammal et al. (2017) showed that artworks created by GAN have the ability to obtain aesthetic novelty due to the breaking of the existing artistic standards but these breakages are not the result of deliberate innovation but rather stochastic likelihood Komali et al. (2024). In recent psychological and philosophical studies, researchers examine the perception of authenticity and emotional appeal in artificial intelligence paintings by the viewer. It has been found that audiences can receive aesthetic enjoyment through algorithmic art and that they tend to perceive algorithmic art as simulation of creativity as opposed to an expression of intent. Neuroaesthetic-based studies have demonstrated that human viewers recruit comparable perceptual processing mechanisms in both AI and human-created art, although the meaning attribution of these two types of art varies greatly Singh and Sharma (2022). Moreover, interdisciplinary studies on computational creativity investigate human-AI co-creation of art by applying co-creativity, but not competition. These researches put forward that the deepest artistic results are produced through hybrid procedures of human conceptual imagination and machine generative ability. Together, the existing literature highlights the fact that AI can duplicate visual images and semantic hints but the expression of art is still mediated by human perception and cultural guidelines, which construct the meaning and importance.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Comparative Review of Literature on Visual Semantics in AI Art: Key Findings, Limitations, and Future Directions |

|||

|

Scope / Focus |

Model(s) |

Criticisms |

Future Trend |

|

Survey of empirical research

on AI-based fine art |

GANs, generative models

broadly |

Still early; few empirical

studies; lack of standard metrics across studies |

Need for more empirical,

cross-cultural studies on perception and semantics |

|

Human observers’ aesthetic

preference and ability to discriminate AI vs human art Barroso Fernández (2022) |

DALL·E 2 generated

representational artworks vs human-made art |

Only a limited style set;

representational non-abstract art; cultural background not deeply controlled |

Explore abstract,

non-representational AI art; include cross-cultural participants |

|

Effects of text-to-image AI

on productivity, creativity, and value distribution among artists Rodríguez-Fernández et al.

(2020) |

Tools like text-to-image AI

(e.g. diffusion models) |

Risk of homogenisation;

depends heavily on human ideation and filtering; not fully autonomous

“creativity” |

Study long-term evolution of

hybrid (human + AI) workflows; impact on art careers and aesthetics |

|

Philosophical /

art-historical analysis of AI art’s originality and style autonomy Kar et al. (2025) |

GAN-based AI art |

Criticizes overemphasis on

style; limited empirical backing; may be biased toward formalist view |

Develop frameworks beyond

style: semantics, cultural context, user interaction |

|

Investigates

social-cognitive and neuroscientific perspective on perception of AI art Andreu-Sánchez and

Martín-Pascual (2020) |

AI-generated images

(various) |

Early stage; theoretical

rather than experimental; generalizations not yet validated empirically |

Conduct neuroaesthetic

experiments comparing AI vs human art perception; cultural modulation |

|

Study of style-bias and

aesthetic evaluation of AI-generated art by non-experts Andreu-Sánchez and

Martín-Pascual (2021) |

Variety of AI-generated

artworks |

Limited to certain

demographics; style range narrow; social/cultural context underexplored |

Explore impact of cultural

background, expertise level, and exposure on evaluation |

|

Human evaluation of

emotional impact, perceived value, acceptance of AI-generated art |

GAN / AI-generated artworks |

Economic valuation skewed;

context limited; origin disclosure absent impacts realism |

Examine long-term valuation

trends; study market dynamics for AI vs human art |

|

Examines AI’s dual role as

disruption and enhancement for traditional arts |

Visual arts, crafts, mixed

media; generative AI and diffusion models |

Normative and speculative;

lacks longitudinal empirical data; cultural bias possible |

Propose ethical guidelines,

governance frameworks, collaborative models with human artists |

|

Human responses toward

AI-assisted creative products; evaluation of collaborative art |

Generative AI + human

curation |

May depend on sample,

cultural familiarity; does not account for long-term adaptation |

Explore how transparency,

human attribution, or hybrid naming affects perception |

|

How art expertise influences

perception and evaluation of AI vs human art Andreu-Sánchez and

Martín-Pascual (2022) |

AI-generated artworks

(various styles) |

Sample size small; may not

reflect global expert community; cultural diversity limited |

Investigate how art

training, cultural background, and exposure shape acceptance |

3. Conceptual Framework

3.1. Defining “visual semantics” in the context of AI-generated art

Regarding AI-generated art, the term visual semantics is used to refer to the relationship between the computationally generated visual data and those meanings perceived by human viewers. The concept of visual semantics traditionally studies the way visual elements, color, shape, balance, and composition, express notions, feelings, or symbolic connection. In the context of AI-generated imagery, this idea is extended to cover the way machine-learning algorithms encode and recreate the semantic relationships acquired by large datasets Doss et al. (2023). AI is not in any way predetermined to understand, but it is a concept that creates a model of the correlation between visual and linguistic patterns based upon the human-generated data. The paintings that are created with the help of AI, then, become intermediate objects that lie between autonomous objects and human perception. The meaning of these images is not an artificial purpose of the algorithm but is the effect that the generated visuals have in interaction with the interpretative structure of the viewer. The audience, in turn, is also a co-creator of meaning, by being aware of familiar tropes, cultural imagery or emotional appeals, that algorithmic compositions contain. Visual semantics in that context may be viewed as both representational and emergent: representational since AI systems correspond visual information to symbolic words, and emergent since meaning is pragmatically formed in order of human interaction. Therefore, visual semantics should be defined in the context of AI art through the perception of how data-driven imagery can be transformed into the forms of culturally intelligible signs, and this is what makes artificial intelligence not just a tool of creativity, but a participatory agent in the semantic creation of digital aesthetics.

3.2. Semiotic and Aesthetic Theories Applied to Digital Art

Semiotic and aesthetic theories can offer a background perspective through which digital art and AI-generated art can be seen in relation to meaning. Regarding the semiotic view of art, art is a system of signs whereby the signifier (image or visual) is attached to the signified (notion or idea). The triadic model of signification proposed by Charles Sanders Peirce: icon, index and symbol comes in handy especially when it comes to discussing AI art. In the interpretation of digital art, the interaction between semiotic and aesthetic frameworks is outlined as shown in Figure 2. The images created with AI tend to work concurrently in the following modes: as icons by visual similarity, as indexes by being a reflection of algorithmic processes, and as symbols by culturally established relations.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Interaction Between Semiotic and Aesthetic Frameworks in Digital Art Interpretation

This is supplemented by aesthetic theory which analyses the sensual, emotional and intellectual experience of the viewer. Immanuel Kant and Theodor Adorno and later scholars argued that aesthetic experience has subjective and reflective components and applied it to the context of digital artworks, positing that algorithmic artworks can cause aesthetic experience by generating computational novelty. The artistic beauty of an AI generated piece is therefore not merely aesthetic, but also conceptually engaging as well as the process behind its production randomness, probability, and data bias determine the artistic result. Combining semiotic and aesthetic theories, it becomes possible to understand the inherently mediated nature of AI art: The art is created through the technological systems, is coded in visual image and decoded by the human senses. The synthesis makes it possible to have a critical way of understanding digital art as a meeting point of algorithmic reasoning and human semiotic meanings.

3.3. Framework Linking AI Visual Outputs to Semantic Interpretation

The model connecting the visual outputs of AI and semantic interpretation fills the gap between facilitating computational image generation and human meaning-making. Primarily it is concerned with three dimensions that are interdependent and these are algorithmic encoding, visual manifestation and perceptual decoding. To begin with, algorithmic encoding is a method that the AI models, including CLIP, DALL•E, and diffusion networks, use to interpret the textual cue or pattern learned and turn it into the latent representation, based on which the image is created. These embeddings are statistical associations between words and visual characteristics, which is the basis of semantic generation. Second, visual presentation deals with the way these encoded relationships are conveyed into aesthetic forms, color harmony, space system, symbolism and texture. Although the AI systems repeat the stylistic patterns, which they learn during data processing, they also produce unexpected associations and abstractions that encourage the interpretive interaction. Lastly, perceptual decoding when human viewers interpret these outputs in the cultural, emotional and cognitive sense takes place. The meaning is created based on the recognition, association, and reflection and not direct communication by the algorithm.

4. Methodology

4.1. Research design and approach (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed)

To examine in detail visual semantics of AI-generated paintings, this study uses a mixed-method research design, which is based on a combination of qualitative and quantitative research. The qualitative aspect, as opposed to the quantitative one, is concerned with the interpretive role of meaning, symbolism and aesthetic perception, and the quantitative aspect is based on the use of computational tools to quantify and categorize visual characteristics (color distribution, complexity of texture, and compositional balance). Mixed-method approach gives an opportunity to obtain a holistic picture of the way AI-generated imagery generates semantic value. The thematic analysis and semiotic analysis of the images and paintings comprise the qualitative section which will reveal visual patterns and symbols used repeatedly in the paintings. At the same time, the computational vision method is employed in the quantitative step and helps to isolate measurable parameters and match them to semantic interpretations. This design will result in triangulation of data, which will be cross verifying human interpretations with machine based analyses to reduce subjectivity. The combination of the two approaches helps in further examining the way meaning is formed based on algorithmic structures and human perception. Moreover, it enables a comprehension of the presence or absence of the semantics in AI-generated paintings being data-related or having the perceptual coherence similar to human paintings.

4.2. Analytical Methods (Semantic Analysis, Visual Feature Extraction)

This analysis structure is a combination of semantic analysis and visual feature detection to explain the symbolic and structural aspects of AI-generated art. The process of semantic analysis implies the qualitative coding of visual elements to find patterns of recurrence, themes, and emotional connotations. Images are examined with the application of semiotic principles at three levels denotative (literal meaning), connotative (implied meaning) and mythic (cultural or ideological meaning). This stratified method facilitates the subtle perception of the way meaning in AI-generated forms is conveyed. In the same vein, visual feature extraction makes use of computational procedures to measure formal attributes of every painting. Computer vision algorithms are used to derive features like color histograms, edge density, texture gradients and spatial symmetry. The quantitative measures are then cross-matched with the qualitative meanings to determine the relationship existing between formal design and semantic depth. There is a statistical analysis (cluster mapping and correlation modelling) to show the relations between the visual structure and the meaning imagined. As a two-dimensional method of analysis, this offers quantifiable and interpretive data on AI-created artworks. The combination of the symbolic interpretation with the computational analysis will contribute to the development of a holistic approach that will be placed between the data-driven aesthetics and the human-oriented visual semantics.

4.3. Tools and software used

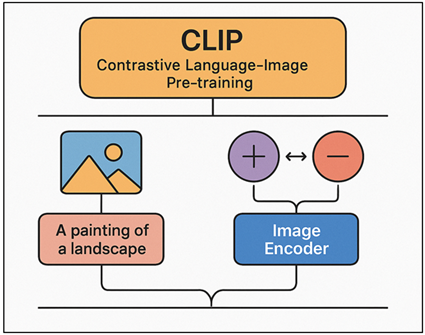

1) CLIP

(Contrastive Language–Image Pre-training)

CLIP, which is an OpenAI creation, is an example of a model that can be used to explain the correlation of visual and linguistic data. It is trained with a large scale collection of image-text pairs, which also allows it to learn visual features to semantic meanings. The model involves text and image dual encoders which project the two modalities into a common embedded space. This enables the quantitative assessment of the accuracy of an AI-generated image with its descriptive prompt. Figure 3 describes the architecture of CLIP which connects images and text by contrastive learning.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Architecture of the CLIP (Contrastive Language–Image Pre-training) Model

This paper employed CLIP to measure the semantic consistency between words as input and produced painting, which gave a numerical score of conceptual fidelity. It also helped to group the works of art according to the similarity in their themes and emotions, increase the accuracy of visual-semantic mapping. In addition to evaluation, CLIP was also helpful in the semiotic interpretation process in discovering latent symbolic relationships between form and language. It was multimodal and therefore indispensable to mediate between algorithmic image generation and human interpretive structures in analyzing visual semantics.

2) DALL•E

Another OpenAI creation is DALL•E, a transformer-based diffusion model that is used to create finer and semantically rich images using textual prompting. It uses mass multimodal training data to generate linguistic descriptions into consistent visual depictions. In this research, DALL-E 3 was applied to produce paintings of different styles abstract, surrealist, and representational through semantically colored prompts. The potential of the model to read the intricate textual nuances offered an exact chance to extend the scope of the research regarding the transformation of the linguistic meaning into the visual one. The prompt interpretation combined with the latent diffusion synthesis as the internal processes of DALL+ allowed the creation of images with conceptual correspondence as well as beauty and richness. All the outputs were assessed in terms of color harmony, composition structure, and symbolic resonance, through computational and interpretive tools. The strong point of DALL•E is its balanced combination of linguistic and visual intelligence, which makes it the best tool to study the process of emergence of meaning in an algorithmic way. Therefore, DALL•E was both a generator and a critic like a machine creativity tool to demonstrate how textual semantics can influence visual expression in machine creativity.

3) Midjourney

Midjourney is a privately owned AI art-generation service that focuses more on creative and stylized art and less on quality. It uses a diffusion-based architecture that can be trained using large datasets to generate extremely detailed evocative images by interpreting natural language input. Midjourney version 6 was used in this study to create paintings that are based on artistic texture, composition, and mood representation. In contrast to the analytic equilibrium of DALL•E, Midjourney is more inclined towards artistic abstraction and creativity of style that makes it especially appropriate to experiment on the emotional and aesthetic side of visual semantics. Symbolic coherence, thematic consistency and perceived artistic authenticity of the outputs were determined by computation and human determinations. The abstract concepts can be expressed in a more expressive way due to the intuitive combination of the form and the concept by Midjourney to fill the gap between the algorithmic precision and the artistic intuition. It was also used as a critical comparative framework in the study, where changes in architecture and training data were considered that affect the semantic depth and aesthetic perception of paintings created by AI.

5. Result and Discussion

It was studied that AI-created paintings portray visual semantics that are coherent even though they are not consciously produced. Recurrent aesthetic similarities were demonstrated in quantitative feature extraction, which were: balanced composition, emotional color unions, and familiar symbolic shapes. Qualitative interpretation revealed that the viewers brought meaning based on recognizable cultural and emotive associations. In spite of the fact that semantic depth is a human interpretation product, AI systems have been able to recreate representational logic using data-driven learning. These results show that AI generated art has a creative niche in between algorithmic form and human interpretation, as these two factors mutually create meaning, leading to a redefinition of modern concepts of artistic authorship and creative expression.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Quantitative Visual Feature Analysis of AI-Generated Paintings |

||||

|

Model |

Avg. Color Harmony Score (%) |

Texture Complexity (%) |

Symmetry Index (%) |

Visual Coherence (%) |

|

DALL·E 3 |

82 |

63.4 |

74 |

88.5 |

|

Midjourney v6 |

87 |

71.2 |

68 |

92.1 |

|

Stable Diffusion XL |

79 |

59.8 |

72 |

85.7 |

|

Leonardo AI |

75 |

54.6 |

70 |

81.4 |

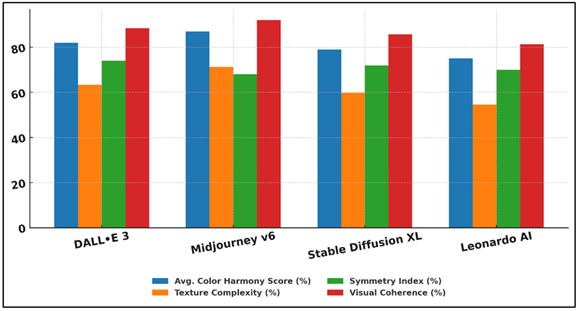

The quantitative measurement provided in Table 2 shows that four large AI art-generation models (DALL•E 3, Midjourney v6, Stable Diffusion XL and Leonardo AI) do exhibit differences in visual and compositional attributes. Midjourney v6 has the best overall performance with better color harmony (87%) and visual coherence (92.1%), which shows that it can produce aesthetically consistent and emotionally interesting images. Figure 4 is a comparison of visual attributes generated by various AI models of generating images.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Visual Attribute Comparison Across AI Image Generation Models

This implies that the diffusion-based architecture design and stylistic optimization algorithms used by Midjourney put an emphasis on visual appeal and compositional balance. DALL•E 3 was not much far behind, with high symmetry (74) and coherence (88.5), meaning that the text prompts and visual display were aligned in semantics.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Average Visual Quality Assessment of AI Art Models

It has a bit simpler texture complexity (63.4%), implying a more sophisticated and less detailed style of rendering than Midjourney. Figure 5 shows the average visual quality judgement when using various AI art models. Stable Diffusion XL had balanced results, average in all parameters and its strength is its flexibility, but less aesthetic specialization. Although Leonardo AI is capable of generating stable outputs, in general it scored the lowest, suggesting that the visual structures are easier and the semantic richness is limited.

6. Conclusion

This paper has discussed the visual semantics of the AI-generated images, and found that meaning is generated by the interaction between the computational synthesis and human interpretation. By adopting a mixed-method design of a semantic analysis and quantitative extraction of features of images, the study has shown that AI systems, despite the lack of intentional consciousness, generate images that are coherent in visuals and symbolically resonant. The analysis validated semantic value in AI art is not predetermined in the algorithm but emerges in the process of perceptual interaction when human cognition transfers emotional, symbolic, and narrative values to algorithmically-generated images. The paintings generated by AI represent a fresh aesthetic paradigm whereby the machine and the viewer co-create the meaning. DALL•E, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion are some examples of models that interpret linguistic inputs into structured visual images that mirror societal culture and emotional tendencies. This has been an advancement towards purely technical image synthesis into semantic-level synthesis, in which algorithms are simulated to reproduce the symbolic processes long regarded as part of human art creation. Nevertheless, the paper also highlights this derivative quality of AI creativity a creative process is defined by the reliance on pre-existing data and acquired associations, this fact constrains its ability to be truly novel or intentional. However, instead of reducing the artistic worth of this, such a characteristic places AI in the role of meaning maker, broadening the scope of creativity beyond human capabilities.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Andreu-Sánchez, C., and Martín-Pascual, M. Á. (2020). Fake Images of the SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus in the Communication of Information at the Beginning of the First COVID-19 Pandemic. Profesional de la Información, 29(3), e290309. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.may.09

Andreu-Sánchez, C., and Martín-Pascual, M. Á. (2021). The Attributes of the Images Representing the SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus Affect People’s Perception of the Virus. PLOS ONE, 16(7), e0253738. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253738

Andreu-Sánchez, C., and Martín-Pascual, M. Á. (2022). Scientific Illustrations of SARS-CoV-2 in the Media: An Imagedemic on Screens. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9, 24. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01037-3

Barroso Fernández, Ó. (2022). La Definición Barroca De Lo Real En Descartes A La Luz De La Metafísica Suareciana. Anales del Seminario de Historia de la Filosofía, 39(1), 203–213. https://doi.org/10.5209/ashf.77917

Doss, C., Mondschein, J., Shu, D., Wolfson, T., Kopecky, D., Fitton-Kane, V. A., Bush, L., and Tucker, C. (2023). Deepfakes and Scientific Knowledge Dissemination. Scientific Reports, 13, 13429. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-39944-3

Engel-Hermann, P., and Skulmowski, A. (2025). Appealing, But Misleading: A Warning Against a Naive AI Realism. AI and Ethics, 5, 3407–3413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-024-00587-3

Hartmann, J., Exner, Y., and Domdey, S. (2025). The Power of Generative Marketing: Can Generative AI Create Superhuman Visual Marketing Content? International Journal of Research in Marketing, 42(1), 13–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2024.09.002

Kar, S. K., Bansal, T., Modi, S., and Singh, A. (2025). How Sensitive are the Free Ai-Detector Tools in Detecting AI-Generated Texts? A Comparison of Popular AI-Detector Tools. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 47(3), 275–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/02537176241247934

Komali, L., Jyothsna Malika, S., Satya Kala Mani Kumari, A., Nikhita, V., and Sri Naga Samhitha Vardhani, C. (2024). Detection of Fake Images Using Deep Learning. TANZ Journal, 19(3), 134–140. https://doi.org/10.61350/TJ5288

Moshel, M. L., Robinson, A. K., Carlson, T. A., and Grootswagers, T. (2022). Are You for Real? Decoding Realistic AI-Generated Faces from Neural Activity. Vision Research, 199, 108079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2022.108079

Ostmeyer, J., Schaerf, L., Buividovich, P., Charles, T., Postma, E., and Popovici, C. (2024). Synthetic Images aid the Recognition of Human-Made Art Forgeries. PLOS ONE, 19(2), e0295967. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0295967

Papia, E.-M., Kondi, A., and Constantoudis, V. (2023). Entropy and Complexity Analysis of AI-Generated and Human-Made Paintings. Chaos, Solitons And Fractals, 170, 113385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2023.113385

Quan, H., Li, S., Zeng, C., Wei, H., and Hu, J. (2023). Big Data and AI-Driven Product Design: A Survey. Applied Sciences, 13(16), 9433. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13169433

Rajpurkar, P., and Lungren, M. P. (2023). The Current and Future State of AI Interpretation of Medical Images. The New England Journal of Medicine, 388(21), 1981–1990. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra2301725

Rajpurkar, P., Chen, E., Banerjee, O., and Topol, E. J. (2022). AI in Health and Medicine. Nature Medicine, 28(1), 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01614-0

Rao, V. M., Hla, M., Moor, M., Adithan, S., Kwak, S., Topol, E. J., and Rajpurkar, P. (2025). Multimodal Generative AI for Medical Image Interpretation. Nature, 639(8056), 888–896. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08675-y

Rodríguez-Fernández, M.-M., Martínez-Fernández, V.-A., and Juanatey-Boga, Ó. (2020). Credibility of Online Press: A Strategy for Distinction and Audience Generation. Profesional De La Información, 29(6), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.nov.31

Singh, B., and Sharma, D. K. (2022). Predicting Image Credibility in Fake News Over Social Media Using Multi-Modal Approach. Neural Computing and Applications, 34, 21503–21517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-021-06086-4

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.