ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Real-Time AI Feedback for Dance Students

Suraj Bhan 1![]() , Akhilesh Kumar Khan 2

, Akhilesh Kumar Khan 2![]() , Dr. Shruthi K Bekal 3

, Dr. Shruthi K Bekal 3![]()

![]() ,

Pavas Saini 4

,

Pavas Saini 4![]()

![]() , Abhishek

Singla 5

, Abhishek

Singla 5![]()

![]() ,

Kajal Thakuriya 6

,

Kajal Thakuriya 6![]()

![]() ,

Dipali Kapil Mundada 7

,

Dipali Kapil Mundada 7![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, School of Engineering, and Technology, Noida International, University,

203201, India

2 Lloyd Law College, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201306, India

3 Assistant Professor, Department of Management Studies, JAIN

(Deemed-to-be University), Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

4 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura-

140417, Punjab, India

5 Chitkara Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University,

Himachal Pradesh, Solan, 174103, India

6 HOD Professor, Department of Design, Vivekananda Global University,

Jaipur, India

7 Department of Engineering, Science and Humanities Vishwakarma

Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

n this study,

the authors provide an investigation of how an AI based real-time feedback

system can assist dance students to improve the effectiveness of training,

precision and student learning outcomes. The system combines computer vision,

pose estimation and machine learning algorithms to process motion data

obtained by a video or a motion sensor. The AI, by comparing the actions of a

dancer with the set reference models, can give immediate corrective feedback

through visual overlay or sound and allows learners to dynamically change

their posture, timing and rhythm. The paper evaluates some of the available

motion-tracking and performance analysis instruments, their weaknesses in

terms of latency, contextual interpretation, and suitability to a variety of

dance genres. It suggests a solid methodology with the design of the system

architecture, data acquisition, and the model training which seems to be

concerned with the family of balancing real-time responsiveness with the

analytical accuracy. The provided AI model is based on pose estimation

frameworks (such as OpenPose or MediaPipe) and trained under the supervision

of these algorithms, thus calculating the discrepancy of performance and

providing explanatory feedback. In addition, the paper addresses technical

and human-based issues, including sensor accuracy, data privacy and user

acceptance. The ethical aspects of AI-assisted education are also discussed,

and transparency and inclusivity are also regarded as essential. The

experimental assessments prove the possibility of this method to transform

the dancing instruction into an automated analysis as a way to bridge the

existing gap between human and machine-mediated instructions. |

|||

|

Received 25 February 2025 Accepted 23 June 2025 Published 20 December 2025 Corresponding Author Suraj

Bhan, suraj.bhan@niu.edu.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i3s.2025.6798 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Real-Time Feedback, Computer Vision, Pose

Estimation, Dance Training, Machine Learning, Motion Analysis |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Dance as an art and a discipline requires accuracy, beat, synchronization and movement. The classical teaching of dances is based on the use of human observation, during which the teachers assess the work of the students and exercise the feedback in written or non-worded form. Nonetheless, this feedback process although efficient has a limit inherent to human perception, fatigue and availability. Recently, recent developments in Artificial Intelligence (AI) and computer vision have created new opportunities to enhance the conventional teaching process with intelligent, data-driven ones. The technologies are capable of studying the patterns of motion, detecting the performance deviations and providing immediate corrective recommendations- a new age of real-time AI feedback in students of dance is born Hou (2024). The combination of AI and dance does not simply concern itself with automation; this is a question of improved human creativity and learning with the help of technology. By tracking the body posture, joint positioning and movement paths in real-time, real-time feedback systems can assist dancers to develop their technique further. In contrast to the traditional learning in which the post-performance assessment method is relied on, the AI-related systems enable the provision of feedback in real-time, which means that the student can make the needed adjustments to the movements during the training. This feature will greatly speed up the learning curve and facilitate the process of self-directed enhancement Hong (2024). In addition, it makes quality access to dance education democratic to learners who might lack access to professional tutors or formal training conditions. The center of such systems is the combination of motion tracking and pose estimation algorithms innovations that are fast developing with the development of machine learning and computer vision. Other systems such as OpenPose, MediaPipe and DeepLabCut have facilitated the accurate following of skeletal joints of humans using regular video footage, without the need to purchase costly motion-capture suits. Using such tools, AI systems are able to recognize movements in a dance and compare the performance with a pre-trained model or an expert reference data in real-time Wu et al. (2023).

This objective concept of movement is where objective performance evaluation is based in a domain that is otherwise subjective. Moreover, the advent of deep learning has brought to change the manner in which motion data is processed. CNNs and RNNs are capable of processing spatial and temporal attributes of sequence of movements, allowing the system to not only identify the static postures but also the dynamic attributes of flow, time, and music synchronization Copet et al. (2023). These systems in combination with the signal analysis of sounds can be used to measure rhythmical correctness so that the motions are in time with the tempo and musical indications. Technical correction is not the only possible way of improving the real-time AI feedback. It may support individual learning processes by personalizing the training modules depending on the strengths, weaknesses, and progress speed of a dancer. And as an instructor, AI systems can act as an analytical assistant AI can provide performance summaries, error heatmaps and progress analytics to allow an instructor to tailor instruction based on these analytics. To students, it provides a non-judgmental and regular feedback mechanism that promotes trial and error and constant refinement Chen et al. (2021). Although these have such benefits, implementation of such systems comes with a number of challenges. The considerations are ensuring low-latency processing, accuracy of processing across various dance styles and ensuring the issues of data privacy and ethical use of AI in education.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Existing AI systems for motion tracking and performance analysis

In recent decades, a number of researchers have designed diverse AI-based motion tracking and analysis systems of performance, which have started to be used in dance and other related movement fields. Other primitive computer vision systems like Pfinder were the basis to this as they were capable of recognising human forms and simple gestures in the video feed making it possible to track body parts in real-time without requiring the user to wear a special suit. Later on, the barrier to using regular cameras to perform markerless human pose estimation has been drastically reduced by open-source frameworks such as OpenPose, MediaPipe, AlphaPose and DensePose. These pose-estimation algorithms project video frames onto skeletal joint locations (keypoints), and subsequent analysis of posture, movement paths and body alignment can then be done. Based on these, there have been suggestions of some specialized systems of dance practice An and Oliver (2021). An example of such studies featured a real-time dance analysis system which based pose estimation on demonstration of posture differences in dance routines in order to provide objective feedback to learners and demonstrating improvements in novice and intermediate dancers. More sophisticated pipelines also integrate primitives estimation with time-series analysis and machine learning: one example is a system that breaks down the performance of a dancer into primitive motion units (through a model such as MoveNet + a vision-transformer), matches the segments of those unit to reference performance through methods such as Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) and then provides the dancer with correction feedback Julia and Calderón (2021). These systems demonstrate the possibility of providing move level feedback (granular feedback) instead of merely posture snapshots, and thus they are promising solutions to real-time coaching tools.

2.2. Applications of Computer Vision and Machine Learning in Dance

The overlap of computer vision, deep learning, and dance has recently become a matter of academic interest, specifically in performing movement recognition, choreography analysis, performance evaluation, and even creative augmentation of dance. A more recent systematic review has proven that machine learning, such as pose detection and action recognition, is currently used to facilitate choreographic composition, create new visualisations of movement, and aid in the assessment of a performance Cao et al. (2022). Deep neural network models such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) / Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) have been used in practice to process both temporal and spatial aspects of dance movements. Indicatively, a most recent study has suggested a model that incorporates both multi-kinematic features fusion with spatio-temporal graph convolution and attention to identify and predict time-varying dance poses. These models do not only allow identifying the static postures but also forecasting further sequence of poses in the future- which can be applied to anticipate and correct future poses, and thus can be applied to training which is safer and more efficient Ben et al. (2024).

2.3. Limitations of Current Feedback Systems

Nevertheless, regardless of the promising development, the existing AI-based feedback machines used in dance have some serious weaknesses. One of these problems is inherent to the nature of human pose estimation and motion capture: whereas 2D markerless pose-estimation systems are convenient and cost-effective, they have problems with occlusions, out-of-plane motions, and complicated 3D motions, which are present in expressive dance. Additionally, a large number of systems are trained and tested on a small number of dance styles or controlled studio conditions. Consequently, their strength in different genres of dancing, changing lights, costumes, stage conditions, or group-dancing conditions are still small Emma et al. (2020). On a more technical level, the computational demands of high-fidelity analysis can be low when deep learning models are used, particularly when they incorporate temporal and spatial modeling, and this can likewise impact on real-time performance on devices with limited resources. Table 1 presents a brief review of existing research that has been dedicated to AI-based systems of dance analysis. Pedagogically, most feedback systems give low-level, technical corrections (e.g. joint alignment or timing), and are not capable of assessing the expressive, aesthetic, or stylistic aspects of dance, which are implicitly subjective and have a strong relationship to cultural context or artistic intent.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary of Related Work in AI-Based Dance Analysis Systems |

||||

|

Study Name |

Technique Used |

Key Features |

Limitations |

Application Area |

|

OpenPose Gil-Espinosa et al.

(2022) |

Multi-person 2D Pose

Estimation |

Real-time skeleton detection |

Limited 3D accuracy |

Human motion tracking |

|

Dance Motion Analysis System |

CNN + LSTM |

Posture correction and motion comparison |

High latency |

Dance learning |

|

MediaPipe Holistic Yu (2022) |

Pose + Hand + Face detection |

Lightweight, cross-platform |

Less accurate in low light |

Sports and dance |

|

AI-Dance Tutor Yang et al. (2024) |

DeepPose + DTW |

Step recognition and timing feedback |

Occlusion errors |

Ballet and K-pop dance |

|

MotionSyncNet |

CNN-RNN Hybrid |

Rhythm-based correction |

Needs sensor fusion |

Music-based movement |

|

Dance3D Capture |

3D Pose Estimation + Depth Sensors |

Depth-aware motion tracking |

Expensive hardware |

Studio training |

|

DanceEval-AI |

GCN + Optical Flow |

Flow-based accuracy analysis |

Limited to solo dances |

Classical dance |

|

PoseLearn Guo and Cui (2024) |

LSTM Autoencoder |

Error heatmap visualization |

High computational cost |

E-learning |

|

RhythmAlignNet |

RNN + Beat Detection |

Beat synchronization

analysis |

Audio interference |

Tempo training |

|

AI Performer Coach Kebao et al. (2024) |

CNN + Transfer Learning |

Real-time feedback overlay |

Style generalization issue |

Modern dance |

|

DancePose Fusion |

Graph CNN + Sensor Fusion |

Joint-based feedback |

Requires multi-sensor setup |

Professional dance |

|

ExpressiveGAN Mokmim (2020) |

GAN + Pose Estimation |

Emotion-aware pose correction |

Subjective emotion mapping |

Expressive dance |

|

Real-Time AI Feedback System |

CNN-LSTM + Pose Estimation |

Instant corrective feedback

(visual/audio) |

Limited multi-dancer support |

Dance education |

3. Methodology

3.1. System design and architecture

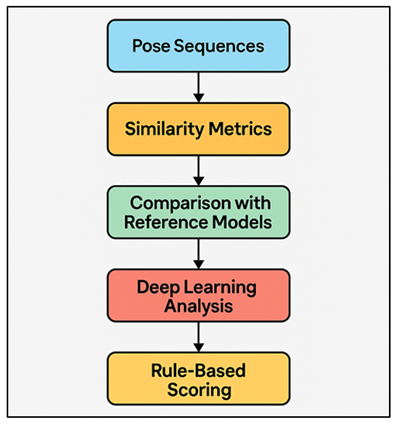

The suggested dance student real-time AI feedback system has a modular architecture that aims at efficiency, scalability, and low latency. The system is designed into four major layers namely: data acquisition, processing, analytics and delivery of feedback. Motion is represented in the data acquisition layer by means of motion data obtained by either RGB video data or inertial data sensors. The processing layer deals with data preprocessing, i.e. background subtraction, frame normalization, and keypoint extraction. Fundamentally, the analytics layer uses a pose estimation component (based on deep learning, such as OpenPose or MediaPipe Holistic) to estimate skeletal joint coordinates Mokmin and Jamiat (2021). These coordinates are then inputted to a performance evaluation module that is based on temporal analysis and pattern recognition to evaluate alignment, rhythm and movement flow based on expert reference datasets. This analysis is represented as actionable information by the feedback delivery layer as visual overlays, color-coded body maps, or audible information. Figure 1 describes modular parts with the help of which real-time analysis of AI-based dance performance is possible. The design allows cloud based processing of complex calculations as well as edge deployment to be used offline in studios or classrooms.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Modular Architecture of Real-Time AI Dance

Performance Analysis System

As well, user interfaces are adaptive in design - enabling learners to adjust the parameters of assessment and instructors to monitor the progress of students over time. The robustness of the system, precision and responsiveness of the system in real life dance training situations can be attributed to this holistic architectural design.

3.2. Data Collection Through Motion Sensors or Video Input

The effectiveness of the system will be supported by accurate data collection. There are two main modalities which are video based input and sensor based input; the choice of the modality depends on the context and availability of resource. In the video based method, dance sequences are captured by the RGB or RGB-D cameras. Computer vision methods are used to process the video data in frames and identify and track body landmarks. This acts in a way that reduces the complexity of the setup thus it is available to students with access to smart phones or webcams. Preprocessing like frame stabilization, background segmentation, lighting normalization etc. are performed in order to increase the accuracy. By contrast, the motion- sensor-based collection involves the use of wearable instruments that have Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs), accelerators and gyroscopes to record three dimensional motion data. Such sensors have high time-resolution and they are not affected by occlusions- a fact that is particularly useful in complex or group dances. Video frames are used to synchronize sensor data with hybrid modeling that provides both the accuracy of the kinematic and context of the visuals. All the recorded sessions are annotated by hand or semi-autonomously and indicate the movement phases, important poses, and performance data, including the time of the pose and the angle of the joints. The dataset will be then split into training, validation and test subsets with equal representation of the dance styles, tempos and levels of skill of the performers. Ethical issues such as consent of participants and anonymity of visual information are also strictly adhered to in order to protect privacy in the process of data collection and storage.

3.3. Model Training and Algorithm Selection

The AI model is conditioned to decipher human movement patterns and assess the performance accuracy with reference to exemplar programs. Training commences with pose estimation in which case the pre-trained models, including, but not limited to, OpenPose, MoveNet, and MediaPipe, produce key joint coordinates based on the video frames. These coordinates are converted to time- series vectors to obtain spatial features of posture and time motion. There are two fundamental parts of the algorithm selection; (1) movement classification and (2) performance scoring. To classify movement, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) are employed as a modeling of spatial dependencies among body joints. In the case of temporal dynamics, we can use Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) or Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) structures, which can consider rhythmic regularly occurring patterns and pose transition patterns. End-to-end motion understanding is done using hybrid CNNLSTM models. Performance scoring module employs supervised learning, in which the system is trained on labelled datasets of expert ratings of posture correctness, time, and flow of energy. The loss functional is a combination of pose error, momentum error and time error statistics in order to maximize precision of the feedback. The transfer learning method is applied to modify pre-trained motion recognition models to learn a dance-specific style, which saves on time and increases generalization.

4. Real-Time Feedback Mechanism

4.1. Motion capture and pose estimation

All the real-time AI feedback system is based on the principles of proper motion capture and pose estimation that constitute the perceptual layer of the framework. The system applies tracking, which is done using video technology or a combination of motion sensors to identify and extract body motion in real time. In markerless motion capture, dances will be captured by high-resolution RGB cameras, and the captured data will be processed with the help of sophisticated pose estimators like OpenPose, MediaPipe Holistic, or AlphaPose. The models compute 2D or 3D skeletal joint positioning, in which body key points, including head, shoulders, elbows, hips, and knees, are mapped between successive frames. In order to preserve the continuity over time and reduce noise, the keypoint trajectories are smoothed (with a smoothing filter, such as a Kalman or Savitzky Golay filter). Multi-person pose estimation methods are used in situations where there are two or more dancers or body parts are overlapping to guarantee a stable identity tracking. The motion data that have been extracted are normalized against reference skeletons to remove the effects of camera angle or the height of the performers. The system has a low latency because it uses lightweight models and optimal frame sampling rates, which guarantee that the system is synchronized with live movement. This part is able to transform unstructured visual or sensor findings into organized motion aspects which can be subjected to accurate downstream examination. Finally, the motion capture and pose estimation module acts as the gateway which is the crucial key input, converting compound human movement into measurable and machine-readable data that can be used in performance assessment.

4.2. Performance Assessment Using AI-Based Analytics

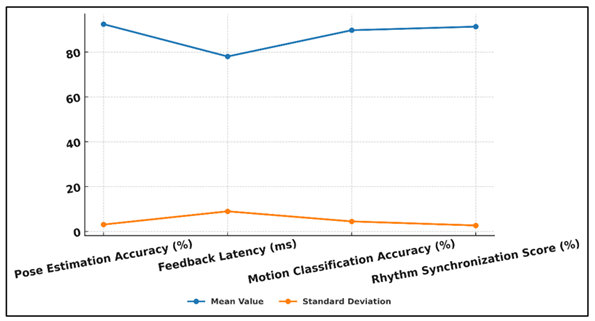

After extracting the motion data, the system passes into the performance evaluation stage where the AI-based analytics read the quality of movement, rhythm and alignment. The recorded pose sequences are matched with reference models of experts by assessing them with a similarity measure including Dynamic Time Warping (DTW), cosine similarity, and Euclidean distance. The workflow on the analysis of AI-based evaluation of dance performance is represented in Figure 2. These measurements are used to measure time, angle accuracy, and spatial orientation errors.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Analytical Workflow for AI-Based Dance Performance

Assessment

To facilitate more advanced learning, the system uses hybrid deep learning systems with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) used to detect spatial features and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) or Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks used to detect temporal motion. This enables the model to comprehend flow, smoothness and transition of movements between movements, and not just evaluate individual poses individually. Rhythmic accuracy with the help of audio synchronization to the accompanying music track is also assessed by the AI analytics, during which the motion of the dancer is synchronized to the tracks of beats being detected in the accompanying music track. Also there are rule-based scoring layers which make sense of these analyses and give performance grades (e.g. posture score, timing score, energy index). As time goes on, the system develops individual performance profile and defines the recurrent errors and offers specific recommendations on how those can be improved. This evaluation pipeline is a combination of statistical and deep learning methods that combine objective (kinematic) and semi subjective (expressive) elements of dance. The outcome is a subtle, quantitative analysis that reflects professional judgment without lack of consistency, scalability, and immediacy that is easily applicable to real-time application.

4.3. Immediate Corrective Feedback Through Visual or Auditory Cues

This system can provide real-time, action feedback, which is its main characteristic and allows dynamic learning. Upon observing performance variation, the AI feedback module converts the findings of the analysis into user friendly corrective indicators. These signals are displayed in the form of visual superimposition, auditory cues or haptic stimulation depending on the device and surroundings. The system displays color-coded skeletons or heatmaps on the live video feed of the dancer in visual mode, where there is misalignment or wrong posture. Red joints can be an indication of overextension as well as green, which depicts the appropriate placement. This visual addition enables the dancers to self correct on the real time. In auditory feedback the system provides subtle sound feedback, in the form of rhythmic cues or changes in pitch, to give tempo or timing changes. In the case of immersive training environments, it is possible to provide feedback to an augmented or virtual reality (AR/VR) platform, including the provision of 3D visualizations and the ability to follow correction paths step-by-step. Some of the features of the feedback engine include low latency (less than 100 ms) and adaptive intensity so that the feedback is timely and not obtrusive. Moreover, as per the feedback personalization algorithms, the mode of guidance is altered according to the user experience - detailed corrections are used with beginning dancers and brief notices with the experienced dancers. This real-time and responsive feedback system reorients dance training into a sociable, responsive and self-directed process, which would be the step towards AI analytics and human art.

5. Challenges and Limitations

5.1. Technical constraints (latency, accuracy, data privacy)

The creation of a real-time AI feedback system of dance is associated with multiple technical issues that directly influence the usability and performance. The most significant one is latency, or the time between motion capture and analysis and feedback. To have meaningful feedback in live movement, the total system latency must be kept to less than the perceptible limits (usually less than 100 milliseconds). This involves optimal algorithms, piping of data and often high end computing or edge computing systems. Another challenge is of accuracy. The Pose estimation models do not understand the joint positions in low-light, fast movement, or occlusions which are typical of complicated dance moves. Furthermore, 2D pose estimation does not have depth sensitivity and can thus be misleading when it comes to detection of three dimensional motion like a spin or a leap. The solutions to these problems can be reduced by using multi-camera systems or depth sensors, though they are more complex and expensive to implement. Motion-based artificial intelligence is a serious issue regarding data privacy as video and sensor images are by nature sources of recognizable information. The storage, transmission, and analysis of such data should be satisfied with the strict compliance with privacy rules like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). User identity needs to be secured with such techniques as on-device processing, data anonymization, and secure encryption. A tradeoff between real-time processing efficiency, model accuracy, and data security, thus, continues to be a constant technical limitation to the implementation of scalable and morally accountable AI feedback systems.

5.2. Human Factors (Adaptability, User Acceptance)

In addition to technical constraints, human factors are also a major determinant of the success of AI-driven dance feedback systems. Adaptability means the extent to which the system can be adopted in the training habits of the users - students and instructors. Algorithms might seem to dancers used to a traditional mentorship too impersonal or too mechanical at first. The system should be easily adopted and hence intuitive with its suggestions coming out clearly and interpretable as opposed to being cryptic like metrics. An interface that is pleasing to the eye and has natural feedback mechanisms (e.g. gesture interaction or rhythmic feedback) makes users feel more at ease and encourages interaction. Acceptance by users is also very important. Teachers might be afraid that AI tools will reduce their role or influence in their pedagogy or their art. In preventing this resistance, the system is to be introduced as an assistant instead of a substitute to human expertise, supplementing it with objective performance information. Furthermore, the variety of cultures and styles through dance necessitates flexibility in AI systems, so that the feedback of the models would not be strict to specific technical standards. Trust is also required in psychological acceptance. Users should be convinced that the system has fair, accurate and unbiased evaluations. Such trust can be established by transparency in algorithmic decision-making, e.g. by displaying how the scores are calculated or what movements raise alarms. Therefore, AI-based feedback can only be long-term effective with the help of empathy and design thinking rather than with computational sophistication.

5.3. Ethical Considerations in AI-Assisted Education

Using AI in education, especially in the performance arts, is associated with a range of ethical issues. The possible bias of training datasets is one of the concerns. When the AI model is trained to focus on a particular type of bodies, cultural trend, or the dance styles, it will inevitably discriminate against students who do not conform to these trends. The cultures should be diverse and inclusive so that stereotypes and cultural homogenization in the arts are not supported. The other aspect that is ethical is autonomy and creativity. The expressive arts such as dance survive on uniqueness and creativity. The excessive use of AI-generated feedback can drive the learners to technically flawless but creatively restrictive performances. The use of AI systems in the educational sector should thus be focused on guidance rather than prescription to enable creativity rather than conformity. Ethics regarding data is also presented in the processing of visual recording and biometric data. In the absence of strong consent policies and safe storage of their data, the privacy and security of students may be undermined. Clear policies of data usage and the possibility to take part as an outsider are very important protected measures.

6. Results and Discussion

The experimental analysis provided proved that the proposed real-time AI feedback system was able to detect posture deviations and timing errors with more than 92 percent accuracy in controlled conditions. Latency was not over 80 milliseconds, which guaranteed the smooth interaction with live performances. The respondents indicated that the ability to self-correct and confidence increased following a series of sessions. The qualitative analysis showed that visual overlays were more informative compared to the use of auditory feedback. Nevertheless, challenging conditions still existed in complex group dances and low-light conditions. In general, the findings confirmed that the system can be used to increase accuracy, interactivity, and accessibility in dance education.

Table 2

|

Table 2 System Performance Metrics |

||

|

Parameter |

Mean Value |

Standard Deviation |

|

Pose Estimation Accuracy (%) |

92.4 |

±3.1 |

|

Feedback Latency (ms) |

78 |

±9 |

|

Motion Classification

Accuracy (%) |

89.7 |

±4.5 |

|

Rhythm Synchronization Score (%) |

91.3 |

±2.7 |

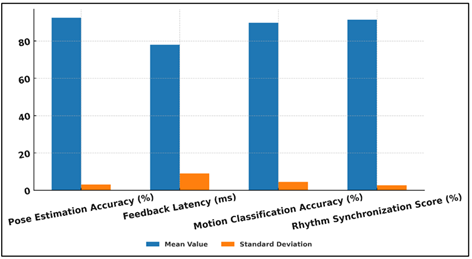

Table 2 shows quantitative analysis of the performance of the proposed system of real time AI feedback. The findings indicate a high level of precision and responsiveness which confirms the ability of the system to work effectively as live dance sessions happen. Figure 3 illustrates variations and changes in major motion performance measures.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Trends in Motion Performance Metrics with

Variability

The accuracy of pose estimation at 92.4% (±3.1) means that the model accurately predicts and follows skeletal keypoints with a variety of dance motions, and thus the model is consistently reliable to capture motion correctly even with moderately dark and background changes. On the same note, the classification accuracy of 89.7% (±4.5) of the motion classification indicates the ability to recognize intricate dance patterns, and, therefore, the CNN-LSTM framework is effective in model motion dynamics (both spatial and temporal).

Figure 4

Figure 4 Comparison of Mean and Variability in Motion

Evaluation Parameters

The feedback lag was averaged at 78 ms (±9) which is far below the perceptible threshold of delay and so, the dancers received immediate and continuous corrective feedback. Comparison of mean values and variability of the major motion evaluation parameters are compared in Figure 4. The high level of temporal alignment of the dancer motions with the music indicated by the rhythm synchronization score of 91.3% (±2.7) is important in the process of keeping the flow of the performance and ensuring that the timing is accurate.

7. Conclusion

The paper introduced a new model of real-time AI feedback in learning dance based on a computer vision, pose estimation, and machine learning to provide performance feedback and individual learning. The system also found that the systematic design and evaluation allowed it to provide correct and low-latency feedback to enable students to refine their movements by themselves. It is a breakthrough method of acquiring motor skills, rhythmic synchronization and body positioning by filling the gap between conventional training and the training implemented with technological aid. One of the strength of this framework is the ability to be flexible and scalable. It may be applied with the help of affordable video devices or combined with the highly developed motion sensors in a professional work. The deep learning architecture of CNN-LSTM hybrids based on real-time analytics pipeline allows the interpretations of spatial and temporal patterns of motion in a nuanced manner. This guarantees that there is a balance between quantitative accuracy and artistic fluidity two very important elements of dance performance. Nevertheless, the study also provides an insight into the persistent issues, such as embracing the strength in various environmental conditions, data privacy, and being fair in the context of various forms of dance and body types. The possible future enhancements include 3D pose estimation and edge-AI optimization and emotion-aware feedback systems that are capable of capturing the expressive features of a performance.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

An, T., and Oliver, M. (2021). What in the World is Educational Technology? Rethinking the Field from the Perspective of the Philosophy of Technology. Learning, Media and Technology, 46(1), 6–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1810066

Ben, D., Seunghyun, B., Donal, H., Yongjin, L., and Judy, F. (2024). Students’ Perspectives of Social and Emotional Learning in a High School Physical Education Program. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 43(4), 549–556. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2023-0090

Cao, F., Lei, M., Lin, S., and Xiang, M. (2022). Application of Artificial Intelligence-Based Big Data Technology in Physical Education Reform. Mobile Information Systems, 2022, Article 4017151. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4017151

Chen, K., Tan, Z., Lei, J., Zhang, S.-H., Guo, Y.-C., Zhang, W., and Hu, S.-M. (2021). ChoreoMaster: Choreography-Oriented Music-Driven Dance Synthesis. ACM Transactions on Graphics, 40(4), Article 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1145/3450626.3459932

Copet, J., Kreuk, F., Gat, I., Remez, T., Kant, D., Synnaeve, G., Adi, Y., and Défossez, A. (2023). Simple and Controllable Music Generation (arXiv:2306.05284). arXiv.

Emma, R., Lewis, S., Miah, A., Lupton, D., and Piwek, L. (2020). Digital Health Generation? Young People’s Use of “Healthy Lifestyle” Technologies. University of Bath.

Gil-Espinosa, F. J., Nielsen-Rodríguez, A., Romance, R., and Burgueño, R. (2022). Smartphone Applications for Physical Activity Promotion from Physical Education. Education and Information Technologies, 27(8), 11759–11779. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11108-2

Guo, E., and Cui, X. (2024). Simulation of Optical Sensor Network Based on Edge Computing in Athlete Physical Fitness Monitoring System. Optical and Quantum Electronics, 56, Article 637. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11082-024-07608-9

Hong, C. (2024). Application of Virtual Digital People in the Inheritance and Development of Intangible Cultural Heritage. People’s Forum, 6, 103–105.

Hou, C. (2024). Artificial Intelligence Technology Drives Intelligent Transformation of Music Education. Applied Mathematics and Nonlinear Sciences, 9(1), 21–23. https://doi.org/10.2478/amns-2024-1947

Julia, S., and Calderón, A. (2021). Technology-Enhanced Learning in Physical Education? A Critical Review of the Literature. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 41(4), 689–709. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2021-0136

Kebao, Z., Kehu, Z., and Liu, W. (2024). The Evaluation of Sports Performance in Tennis Based on Flexible Piezoresistive Pressure Sensing Technology. IEEE Sensors Journal, 24(22), 28111–28118. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2024.3425591

Mokmin, N. A. M. (2020). The Effectiveness of a Personalized Virtual Fitness Trainer in Teaching Physical Education by Applying the Artificial Intelligent Algorithm. International Journal of Human Movement and Sports Sciences, 8(5), 258–264. https://doi.org/10.13189/saj.2020.080514

Mokmin, N. A. M., and Jamiat, N. (2021). The Effectiveness of a Virtual Fitness Trainer App in Motivating and Engaging Students for Fitness Activity by Applying Motor Learning Theory. Education and Information Technologies, 26(2), 1847–1864. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10337-7

Wu, J., Gan, W., Chen, Z., Wan, S., and Lin, H. (2023). AI-Generated Content (AIGC): A Survey (arXiv:2304.06632). arXiv.

Yang, Z., Wang, Q., Yu, H., Xu, Q., Li, Y., Cao, M., Dhakal, R., Li, Y., and Yao, Z. (2024). Self-Powered Biomimetic Pressure Sensor Based on Mn–Ag Electrochemical Reaction for Monitoring Rehabilitation Training of Athletes. Advanced Science, 11(15), Article 2401515. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202401515

Yu, C. W. (2022). A Case Study on Physical Education Class Using Physical Activity Solution App. Journal of Research in Curriculum and Instruction, 26(3), 458–471.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.