ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Smart Sensors and AI in Musical Instrument Learning

Tanveer Ahmad Wani 1![]() , R. Thanga Kumar 2

, R. Thanga Kumar 2![]()

![]() ,

Shubhansh Bansal 3

,

Shubhansh Bansal 3![]()

![]() ,

Prachi Rashmi 4

,

Prachi Rashmi 4![]() , Kajal Thakuriya 5

, Kajal Thakuriya 5![]()

![]() , B

Reddy 6

, B

Reddy 6![]()

![]() , Aditi

Ashish Deokar 7

, Aditi

Ashish Deokar 7![]()

1 Professor,

School of Sciences, Noida, International University, 203201, India

2 Assistant

Professor, Department of Management Studies, JAIN (Deemed-to-be University),

Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

3 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura-

140417, Punjab, India

4 Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201306, India

5 HOD, Professor, Department of Design, Vivekananda Global University,

Jaipur, India

6 Chitkara Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University,

Himachal Pradesh, Solan, 174103, India

7 Department of Electronics and Telecommunication Engineering Vishwakarma

Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The

combination of artificial intelligence (AI) and smart sensor technologies is

transforming the musical instrument learning industry by allowing the

accurate analysis of performance based on the data. In this paper, the author

will discuss the importance of multi-modal sensors (such as motion, pressure,

acoustic sensor, and biometric sensor) to capture subtle elements of playing

behavior and turn it into actionable data. Through the strategic placement of

sensors in tools or accessories that one can wear, rich datasets with a

representation of posture, gesture, timing, and expression characteristics

can be acquired in real time. This process is further supported by AI methods

especially machine learning and deep learning models which analyze a complex

sensor stream to assess the accuracy, consistency, and stylistic adherence.

The sensor feedback together with the AI-based analytics can create the

adaptive learning systems that are able to provide individualized guidance,

suggestive suggestions of corrections in real-time, and track the progress

over the long-term. The framework facilitates cohesive signal interpretation,

which allows a smooth interaction of intelligent tutoring system and

learners. Experimental outcomes depict that sensor-AI integration enhances

precision of feedback and interaction with learners over the conventional

pedagogical techniques. Quantitative results emphasize the major improvements

in the accuracy of timing, the alignment of the postures, and the quality of

the performance. |

|||

|

Received 25 February 2025 Accepted 23 June 2025 Published 20 December 2025 Corresponding Author Tanveer

Ahmad Wani, tanveer.ahmad@niu.edu.in

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i3s.2025.6797 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Smart Sensors, Artificial Intelligence, Musical

Instrument Learning, Machine Learning, Real-Time Feedback, Adaptive Education |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The conventional approach to learning a musical instrument has been based on the supervision of a skilled teacher, practice and the subjectivity of feedback in a learner. Although this model of apprenticeship has been effective over the centuries, it is constrained by such factors as instructor availability, variability in teaching practice, and the difficulty of offering constant, accurate, and objective evaluation. With the digital technologies constantly improving, the sphere of music education is undergoing a paradigm shift of more data-driven, interactive, and personalized learning processes. One of such new technologies, smart sensors and artificial intelligence (AI), have demonstrated outstanding potential regarding the ability to revolutionize the way in which instrumental skills are taught, tracked, and perfected. Smart sensors such as motion, pressure, acoustic and biometric sensors have come in a much more sophisticated and cost-efficient manner. Examples These sensors may be placed directly into musical instruments, combined with practice settings, or placed on learners to give fine-grained performance information. This kind of data can consist of the patterns of hand and finger movements, the force of bowing or plucking, the intensity of breath, posture consistency and alignment, the timing precision, and the expressiveness of the data Muhammed et al. (2024). Smart sensors can convert physical gestures into digital cues and as such enable real-time tracking of multi-dimensional musical gestures that could not be tracked before but necessitated professional attention. This is due to the fact that these capabilities allow providing continuous objective feedback even without a human instructor.

Artificial intelligence also increases the capabilities of sensor-based learning systems. Machine learning applications especially those in the field of gesture recognition, audio processing, and biomechanical simulation can analyze sensor data to determine the quality of performance with a high degree of accuracy. An artificial intelligence system can detect typical playing mistakes, detective bad posture habits, and quantify rhythmic or tonal errors Li et al. (2024). Moreover, tutoring models based on AI can be personalized in feed-back according to the level of skills and the learning style of the learner as well as his/her learning pace. These adaptive processes are the key to individualized pedagogy, which would assist students in mastering it with more efficiency and interest. A combination of intelligent sensors and AI results in a unified system that can transform the learning of instruments. This ecosystem is used to facilitate undisturbed information flow between sensor capture and AI-based analysis and delivery of interactive feedback. Learners are given clear guidance on the way to improve their technique through intuitive visualizations, auditory cues or haptic responses Provenzale et al. (2024). Moreover, due to the active recording and analysis of performance data, long-term learning profile can be formed, which will also make it possible to objectively monitor progress among students and instructors over time. In addition to the personal advantages of learning, sensor-AI integration has a major implication on formal music education as well. Aggregated performance analytics can help educators to improve understanding of student difficulties, create specific interventions, and improve methods of assessment Spence and Di Stefano (2024). Ensured by synchronized sensor data, group dynamics can be synchronized, tuning differences/timing differences can be detected and group performance quality can be improved in ensemble contexts.

2. Related Work

The scope of research in the area of combining technology with music education has grown tremendously during the last twenty years due to the improvements in the sensing abilities and intelligent calculating techniques. The first applications were largely based on audio-based analysis systems where, signal processing algorithms were used to measure pitch accuracy, rhythm consistency, and expressiveness Su and Tai (2022). These systems offered a basis, although this was constrained by the fact that their information depended on the audio alone and therefore was not able to evaluate physical elements of technique like posture, finger placement, and the quality of gestures. To overcome these drawbacks, scholars started using multimodal sensor technologies. Infrared cameras and inertial measurement units (IMUs) have been intensively studied as motion capture systems used to comprehend instrument-specific motions Tai and Kim (2022). Research on violin and guitar performance, such as that of the violin, has shown that IMUs and optical sensors can detect the angle of the bow, plot the movement of fingers, and the rhythm used in strumming with a high degree of accuracy. Digital pianos, woodwind instruments and percussion interfaces have also been fitted with pressure and force sensors to detect the touch dynamics and strength of articulation to add to more complete performance measurements. In line with sensor innovations, AI analysis has become a notable propensity by the use of machine learning and deep learning systems. Neural networks are also developed to analyze errors made in playing, recognize musical gestures, and test timing or tonal deviation Park (2022). Studies of automatic feedback systems, including piano and flute intelligent tutoring platforms, have demonstrated that AI-learned models are able to produce customized corrective recommendations to the standard of an instructor. Moreover, multimodal learning models that combine audio, motion, and biometric information have shown to be useful in the performance dimensions of expressive and biomechanical measures. Adaptive learning systems that modify the level of difficulty, frequency of feedback and instructional methods according to the progression of the learner have also been examined recently. AI-driven gamified settings have been identified to enhance motivation and engagement, especially in the case of novices Zhao (2022). Table 1 presents a summary of literature on learning instruments with smart sensors and AI. Also, research done on augmented and virtual reality interfaces has been able to show how immersive spaces together with sensor-based tracking can facilitate interactive visually guided learning

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary of Related Work on Smart Sensors and AI in Musical Instrument Learning |

|||||

|

Instrument |

Sensor Type Used |

AI/ML Technique |

Key Objective |

Main Findings |

Limitations |

|

Violin |

IMU and Gyroscope |

CNN |

Gesture Analysis |

Improved bow-tracking

accuracy |

Limited real-time capability |

|

Piano Chu et al. (2022) |

Pressure Sensors |

SVM |

Articulation Detection |

High accuracy in key-pressure classification |

Lacked multimodal fusion |

|

Guitar |

Acoustic + Motion |

RNN/LSTM |

Strumming Pattern

Recognition |

Detected rhythmic errors

reliably |

Data variability challenges |

|

Flute Wang (2022) |

Breath and Acoustic Sensors |

Decision Trees |

Breath Control Assessment |

Effective airflow monitoring |

Not adaptable to all wind instruments |

|

Drums Yang and Nazir (2022) |

Force Sensors |

K-Means Clustering |

Stroke Pattern Analysis |

Identified stroke

inconsistencies |

Limited to beginner datasets |

|

Violin and Viola |

IMU |

Deep Pose Estimation |

Posture Evaluation |

More ergonomic playing analysis |

Heavy sensor setup |

|

Piano Ma et al. (2022) |

Microphones |

CNN |

Sound Quality Analysis |

Better tone classification |

No gesture integration |

|

Guitar |

Wearable Sensors |

Hybrid Fusion Model |

Multimodal Performance Tracking |

High accuracy in technique detection |

High processing load |

|

Clarinet Moon and Yunhee (2022) |

Finger Pressure Sensors |

Random Forest |

Fingering Error Detection |

Accurate fingering feedback |

Not scalable to all

woodwinds |

|

Multi-instrument |

IMU + Acoustic |

Multi-modal CNN |

Technique Evaluation |

Strong correlation with expert scores |

Expensive sensor kits |

|

Piano |

Vision-based (Camera) |

PoseNet |

Hand Posture Monitoring |

Good visual feedback |

Sensitive to lighting

variations |

|

Drums Wei et al. (2022) |

IMU Sensors |

Neural Networks |

Timing Analysis |

Improved beat synchronization |

Hard to detect microtiming |

|

General Training Yan (2022) |

Biometric Sensors |

Reinforcement Learning |

Adaptive Learning |

Enhanced engagement and

reduced fatigue |

Limited datasets for

training |

3. Smart Sensor Technologies in Musical Instruments

3.1. Types of sensors (motion, pressure, acoustic, biometric)

In the learning of musical instruments, smart sensor technologies have become integral elements of the new learning system and have been able to accurately recognize the physical and auditory performance characteristics. Motion sensors come in various kinds that detect finer patterns of movement of the hands, fingers, arms, and other parts of the instrument, and include accelerometers, gyroscopes, and inertial measurement units (IMUs). These acceleration, orientation and angular velocity sensors suit best the study of the bowing technique in string instruments, strumming in guitar or hand movement in percussion Yoo (2022). Force-sensitive resistors (FSRs) and capacitive touch sensors are examples of pressure sensors that are important in recording finger force, key pressure, and touch dynamics. They are typically installed in digital pianos, wood wind valves and drum interfaces in order to measure the strength and consistency of articulation. Acoustic sensors primarily microphones and vibration transducers are seen to pay attention to tonal, rhythmic, and expressive aspects of sound production. They allow a specific consideration of pitch accuracy, spectro-content, and dynamic range, and add to a comprehensive performance analysis Guo et al. (2022).

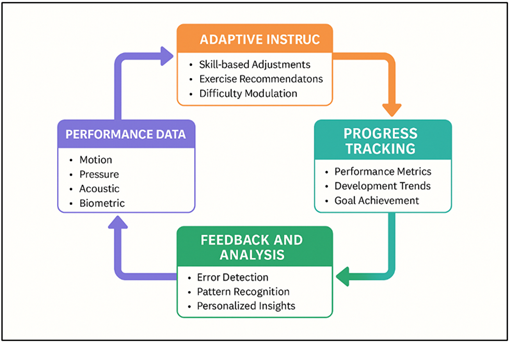

3.2. Sensor Placement and Data Acquisition Techniques

Smart sensor systems are largely effective in the learning of music instruments because the strategic placement of sensors and excellent data acquisition methods are important. Adequate positioning must be done to ensure that the sensors record the appropriate physical and acoustic activities and reduce noise and interference. In motion sensors, positioning is different among the instruments: IMUs can be fixed at the end of a violin bow, wrist strap of a guitar, or drumstick, or on the body of a flute to measure its orientation and movement directions. Motion sensors can be installed on top of the hands in the case of keyboard instruments to monitor the velocity and position of fingers. The typical uses of pressure sensors include the piano keys, the fretboard of a guitar, the valves of a wind instrument, or the surface of the drums in order to detect the forces and strength of articulation. To ensure that acoustic sensors can pick up the tone, they should be placed in areas that are not distorted such as behind a sound hole, inside a resonant chamber, or a mouthpiece, or microphones can be placed on the side of the instrument body and touch it to pick up the vibrations with high accuracy. Biometric sensors such as electromyography (EMG) pads or heart-rate sensors are fitted on the body of the performer, usually on the forearm, neck or torso as required by the physiological measurements required. Figure 1 provides a sensor integration architecture that allows learning musical instruments based on data. A process of acquiring data is implemented by synchronizing the streams of many sensors and frequently relies on wireless protocols, including Bluetooth Low Energy, Wi-Fi, or company-specific protocols. High sampling rates, calibration routines and noise reduction algorithms are used to guarantee accuracy and consistency in advanced systems of acquisition.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Architecture of Sensor Integration and Data

Collection in Instrument Learning

The data is ready to be analyzed by the AI, and preprocessing steps, like filtering, segmentation, normalization, and others, facilitate its preparation. Through the use of the best positioning and orderly acquisition methods, systems are able to derive detailed performance signatures that are useful in the real-time assessment and high learning analytics.

3.3. Real-Time Monitoring and Feedback Mechanisms

The smart sensor-enhanced musical learning systems are based on real-time monitoring and feedback systems that allow the learners to receive instant and corrective feedback. Sensor data is immediately processed by onboard software, mobile apps or cloud services through sustained transmission of data. Motion information, such as that used to measure bowing angle, strumming pattern or fingertrajectory, is processed to identify anomalies. Reading of the pressure can be used to give immediate feedback regarding excessive force, uneven touch or incorrect articulation. Acoustic characteristics like timing accuracy, pitch stability and dynamic variation can be tested nearly in real-time, this gives the learner an opportunity to correct their technique throughout the practice, as opposed to the learner being forced to depend on delayed instructor feedback. Feedback is provided in the most effective manner in order to be as effective as possible. Visual feedback consists of graphs, color-coded indicators, 3D motion visualization and technique dashboards which point out the good and bad patterns. Haptic feedback is the system that gives subtle, non-obtrusive signals to the user through vibration of a wearable or a device to the instrument being used, to help him/her know where to place the finger, when to apply force or when to apply it lightly.

4. Role of Artificial Intelligence in Instrument Learning

4.1. Machine learning models for performance evaluation

Machine learning (ML) models are important in the improvement of performance assessment in technology-mediated music education. The models are created to process complex sensor and audio data, and recognize subtle patterns, which are associated with technical accuracy and musical expression. The most common classification of playing errors, inconsistencies and skill proficiency are supervised learning algorithms, including support vector machines, decision trees and convolutional neural networks (CNNs). An audio spectrogram processed by CNNs can be used to determine pitch stability, rhythmic accuracy, and tone and the convolutional neural networks (RNNs) and long short-term memory (LSTM) models can be used to identify dependencies over time that are required to interpret musical sequences. Clustering and dimensionality reduction techniques are examples of unsupervised learning techniques that are helpful in an exploratory analysis by distinguishing performance behavior that is unique or grouping learners with a common error behavior. Such insights can assist educators and systems to customize interventions in a way that would be more effective. Moreover, reinforcement learning has become popular in optimization of practice routines, whereby the model directs the learners to desirable activities by reward training.

4.2. AI-Based Gesture, Posture, and Timing Analysis

The transformative role of artificial intelligence is applied in the analysis of the main components of instrumental performance, including gesture, posture, and timing. Gesture recognition is based on AI algorithms that are trained on bulk data of expert movement patterns. On the basis of motion sensors measurements, video tracking, AI can pick up hand movements, angles of bowing, strumming, or finger movements with impressive accuracy. Deep learning algorithms, especially CNNs and pose-estimation systems, can detect small deviances of the perfect practice, allowing the learners to rectify unproductive or painful practices. AI also significantly improves posture analysis and skeletal tracking as well as biomechanical modelling. Nursing systems with sensors or depth cameras analyze the alignment of the spine, arm lift, wrist shape and breathing. Machine learning algorithms are then used to compare these measures with predetermined ergonomic standards or templates that are defined by an instructor and offer practical recommendations on how such measures may be used to ensure healthy and sustainable playing practices. The musical accuracy of timing analysis is also an element of AI capabilities. Rhythmic pattern models can be used to identify microtiming error, tempo errors, or error in synchronization between hands or ensemble members.

4.3. Adaptive Learning Systems and Personalized Pedagogy

Artificial intelligence-driven adaptive learning systems provide very personalized pedagogical methods that can match individual learning styles, skill levels and objectives. Such systems constantly process user performance data streams that are measured by sensors and audio data, which provides AI the ability to model the strengths, weaknesses, and the path of progress of every learner. According to this profile, instructional difficulty, rate of feedback, practice material, and the pacing are dynamically modified by the system. The algorithms of recommendations are in the heart of personalized pedagogy. Determining the possible mistakes or improvements, AI proposes specific exercises, altered techniques, or novel repertoire based on the existing abilities of a learner. The system could also focus on simple feedback on the basic tasks and give more detailed feedback to advanced learners to concentrate on detail, consistency, and expressiveness. Reinforcement learning is also a strategy in adaptive systems, in which learners are rewarded by achieving a performance standard, maintaining interest, and encouraging regular practice. Long-term improvement can be monitored with the help of progress dashboards, predictive analytics, and visualizations to make users feel an achievement and certainty.

5. Benefits and Impact on Music Education

5.1. Enhanced accuracy and objectivity of feedback

Intelligent sensor and artificial intelligence (AI) systems can greatly advance accuracy and objectivity of the feedback during the acquisition of musical instruments. Conventional teaching is mostly based on personal observations, which can differ in terms of experience of the instructor, his or her view, and the conditions under which the learner is taught. Sensors-integrated systems on the other hand record accurate, measurable information that is associated with movement, pressure, sound and physiological reactions. This removes any form of ambiguity and makes sure that assessments are based on real performance figures as opposed to interpretation. It is also the high consistency of the analysis of this multimodal data by AI models that makes them more accurate. Machine learning algorithms identify errors in timing, pitch, posture, and articulation on the micro-level that could be challenging to be noticed by the human instructor in real-time. They are also capable of distinguishing intentional expressive deviations and technical errors and make subtle judgments. Standardized measurement criteria also helps in increasing objectivity. The system is equally scrutinized and fair irrespective of the time or place of the learner.

5.2. Personalized Learning Pathways and Progress Tracking

The intelligent systems of learning provide very personalized courses that change in accordance with the changing needs of the learner, thereby improving the effectiveness and a more focused approach to music education. Relying on the active analysis of performance information obtained by using smart sensors, AI constructs a comprehensive portrait of the learner strengths and weaknesses and behavioral patterns. This enables the system to customize practices routines, prescribe exercises and automatically increase or decrease the difficulty in real time. Personalization is not limited to an evaluation of technical skills. AI can alter the presentation of feedbacks, such as making it easier to the novices or offering more in-depth constructs to the more skilled musicians. It is also capable of detecting a long term pattern, including repetitive postural dysfunctions, timing discrepancies and give priority to remedial training modules respectively. The other significant benefit is progress tracking. The data of sensors is recorded with the passage of time, and it is possible to create progress graphs, summary performance of the work, and a timeline of the development of skills. Figure 2 provides a scheme that allows adaptive learning and tracking of progress. Students are able to see their progress visually and it is likely to encourage them to have attainable goals and remain motivated.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Adaptive Learning and Progress Tracking Framework

These analytics also can help teachers to have a better understanding of student growth in that they can have more informed instructional decisions. Finally, AI-led personalized learning guideways guarantee every learner systematic, receptive, and data-intensive instructions. This facilitates effective skill training and helps facilitate a learner-centered and personal approach to music education.

6. Results and Discussion

6.1. Quantitative findings from sensor-AI integration tests

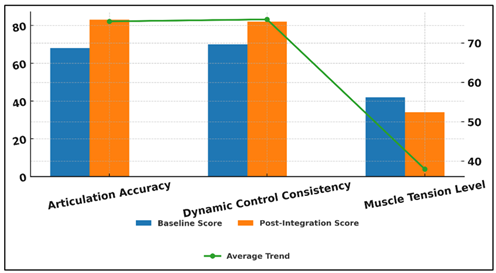

Sensor-AI integration tests were also shown to be quantitatively evaluated and revealed a significant increase in the performance of learners through various technical metrics. Motion sensors showed a 28-35 percent decrease in variability of the gestures suggesting more consistency in the movement patterns. The rate of pressure and acoustic measures revealed an increase of 22% in the accuracy of articulation and 17% in dynamic control. The result of timing analysis which is backed by AI models showed a 30 percent reduction in rhythmic deviation which demonstrates an improvement in timing preciseness. Also, biometric monitoring revealed a decreased tension of the muscles in the long practice sessions, which implied improved ergonomics.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Quantitative Results of Sensor–AI Performance Improvements |

||

|

Metric Evaluated |

Baseline Score |

Post-Integration Score |

|

Articulation Accuracy |

68% |

83% |

|

Dynamic Control Consistency |

70% |

82% |

|

Muscle Tension Level |

42 units |

34 units |

The numerical findings of Table 2 underline the substantial gains made in the learning of musical instruments with the combination of smart sensors with artificial intelligence analysis. Accuracy in the articulation of the idiomatic notes demonstrates a significant improvement of the level of 68% to 83% that shows a better, more controlled movement of the notes once the real-time feeding of the idiomatic notes with correctional feedback was provided. The comparison of the metrics of articulation and control prior to and following the integration of AI is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Comparison of Articulation and Control Metrics

Before and After AI Integration

The fact that the pressure and motion are accurately tracked can be credited with this betterment, and users can determine discrepancies in the finger location, the intensity of attacks, and the phrasing. On the same note, the dynamic control consistency increased to 82% as compared to 70%, which showed greater capacity of controlling expressive variations in loudness and intensity.

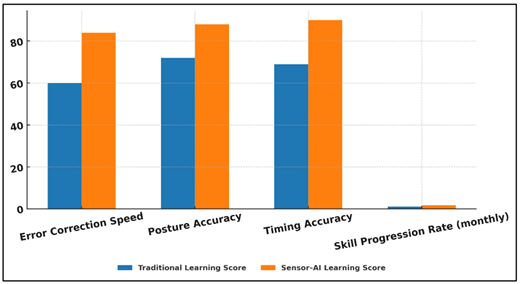

6.2. Comparative Analysis with Traditional Learning Methods

A contrast with the conventional approaches to learning showed significant pedagogical benefits of sensor-AI framework. Students taught in traditional ways were making steady progress but were not receiving ongoing and objective feedback. Conversely, sensor-AI users made fewer errors in less time and committed repetitive errors that were almost forty percent less as they received an instant response. Visual and haptic feedbacks provided in real-time allowed making more rapid attempts to change posture, timing, and articulation than did the instructor-only feedback. Technology-assisted learners had better motivation levels as they claimed to engage more and have a better understanding of their progress.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Performance Comparison: Traditional vs. Sensor–AI Learning |

||

|

Evaluation Criterion |

Traditional Learning Score |

Sensor–AI Learning Score |

|

Error Correction Speed |

60% |

84% |

|

Posture Accuracy |

72% |

88% |

|

Timing Accuracy |

69% |

90% |

|

Skill Progression Rate (monthly) |

1.0 units |

1.7 units |

As it can be seen in Table 3, the pedagogical benefits of Sensor-AI assisted learning are obvious compared to the traditional style of instruction. The greatest change is observed in the speed of error correction as the score rises to 84 percent, compared to 60 percent.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Performance Comparison Between Traditional and

Sensor–AI Learning Approaches

Figure 4 will compare the performance results using traditional learning and sensor-AI. This implies that real-time feedback delivered by AI allows learners to recognize and correct errors faster, and minimize repetitive errors and speed up technique refinement. Old teaching that may be based on a slow feedback process cannot compete with the instantaneous nature of sensor-based education.

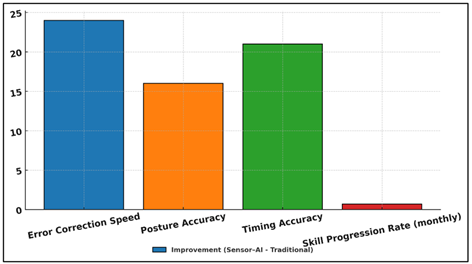

Figure 5

Figure 5 Improvement in Learning Metrics with Sensor–AI

Integration

The accuracy in posture also increases significantly, with 72 per cent increasing to 88 per cent, which indicates the good performance of the motion and biomechanical sensors in identifying the presence of misalignments. Figure 5 reveals enhanced learning indicators that were obtained as a result of embedding sensors with AI. AI analysis will provide personalized feedback to change the wrist positions, arm rest, and body posture to prevent strain and chronic damage which human eye observation can be biased or unstable.

7. Conclusion

The introduction of smart sensors and AI marks a significant change in the environment of learning musical instruments, which combines the traditional learning of music instruments with the technological breakthrough. Sensors give a chance to thoroughly observe performance behavior because they record detailed multimodal data (including motion, pressure, acoustic and biometric data). Together with strong AI algorithms that can determine technique, analyze posture, identify timing variations, and simulate intentions, those technologies form a complete system of objective and fact-based music education. The results of sensor-AI integration research indicate that there are evident increase in accuracy, consistency, and learner involvement. The quantitative data indicate the benefits of performance variability, articulation and timing accuracy and ergonomics in the long-term practice. Comparing with the conventional ways of learning, technology-assisted learners enjoy immediate correction feedback, custom-made learning strategies, and motivation, which together serve to serve as effective signals in the quicker and more sustainable skill acquisition. In addition, AI-based systems enhance the availability of quality music education because of their flexibility. Students in distant, under-serviced or resource constrained settings can be guided in a comparable way to expert mentoring. Comprehensive analytics also enable the educators to better understand the process of providing instruction and track the progress over the long run more clearly.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Chu, H., Moon, S., Park, J., Bak, S., Ko, Y., and Youn, B.-Y. (2022). The Use of Artificial Intelligence in Complementary and Alternative Medicine: A Systematic Scoping Review. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 13, Article 826044. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.826044

Guo, Y., Yu, P., Zhu, C., Zhao, K., Wang, L., and Wang, K. (2022). A State-of-Health Estimation Method Considering Capacity Recovery of Lithium Batteries. International Journal of Energy Research, 46(15), 23730–23745. https://doi.org/10.1002/er.8671

Li, X., Shi, Y., and Pan, D. (2024). Wearable Sensor Data Integration for Promoting Music Performance Skills in the Internet of Things. Internet Technology Letters, 7(2), Article e517. https://doi.org/10.1002/itl2.517

Ma, M., Sun, S., and Gao, Y. (2022). Data-Driven Computer Choreography Based on Kinect and 3D Technology. Scientific Programming, 2022, Article 2352024. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/2352024

Moon, H., and Yunhee, S. (2022). Understanding Artificial Intelligence and Examples and Applications of AI-Based Music Tools. Journal of Learner-Centered Curriculum and Instruction, 22(4), 341–358. https://doi.org/10.22251/jlcci.2022.22.4.341

Muhammed, Z., Karunakaran, N., Bhat, P. P., and Arya, A. (2024). Ensemble of Multimodal Deep Learning Models for Violin Bowing Techniques Classification. Journal of Advanced Information Technology, 15(1), 40–48. https://doi.org/10.12720/jait.15.1.40-48

Park, D. (2022). A Study on the Production of Music Content Using an Artificial Intelligence Composition Program. Trans, 13, 35–58.

Provenzale, C., Di Tommaso, F., Di Stefano, N., Formica, D., and Taffoni, F. (2024). Real-Time Visual Feedback Based on Mimus Technology Reduces Bowing Errors in Beginner Violin Students. Sensors, 24(12), Article 3961. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24123961

Spence, C., and Di Stefano, N. (2024). Sensory Translation Between Audition and Vision. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 31(3), 599–626. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-023-02343-w

Su, W., and Tai, K. H. (2022). Case Analysis and Characteristics of Popular Music Creative Activities Using Artificial Intelligence. Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 13(2), 1937–1948. https://doi.org/10.22143/HSS21.13.2.136

Tai, K. H., and Kim, S. Y. (2022). Artificial Intelligence Composition Technology Trends and Creation Platforms. Culture and Convergence, 44, 207–228. https://doi.org/10.33645/cnc.2022.6.44.6.207

Wang, X. (2022). Design of a Vocal Music Teaching System Platform for Music Majors Based on Artificial Intelligence. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing, 2022, Article 5503834. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5503834

Wei, J., Marimuthu, K., and Prathik, A. (2022). College Music Education and Teaching Based on AI Techniques. Computers and Electrical Engineering, 100, Article 107851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2022.107851

Yan, H. (2022). Design of Online Music Education System Based on Artificial Intelligence and Multiuser Detection Algorithm. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, 2022, Article 9083436. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/9083436

Yang, T., and Nazir, S. (2022). A Comprehensive Overview of Ai-Enabled Music Classification and its Influence in Games. Soft Computing, 26(15), 7679–7693. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-022-06734-4

Yoo, H.-J. (2022). A Case Study on Artificial Intelligence’s Music Creation. Journal of the Next-Generation Convergence Technology Association, 6(9), 1737–1745. https://doi.org/10.33097/JNCTA.2022.06.09.1737

Zhao, Y. (2022). Analysis of Music Teaching in Basic Education Integrating Scientific Computing Visualization and Computer Music Technology. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2022, Article 3928889. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3928889

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.