ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Machine Learning for Music and Movement Coordination

Krishna Reddy BN 1![]()

![]() ,

Ansh Kataria 2

,

Ansh Kataria 2![]()

![]() ,

Vijayendra Kumar Shrivastava 3

,

Vijayendra Kumar Shrivastava 3![]()

![]() ,

Madhur Grover 4

,

Madhur Grover 4![]()

![]() ,

Durga Prasad 5

,

Durga Prasad 5![]() , Nishant Kulkarni 6

, Nishant Kulkarni 6![]()

1 Associate

Professor, Department of Management Studies, JAIN (Deemed-to-be University),

Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

2 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

3 Professor, Department of Mangement, Vivekananda Global University,

Jaipur, India

4 Chitkara Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University,

Himachal Pradesh, Solan, 174103, India

5 Associate Professor, School of Engineering, and Technology, Noida, International,

University,203201, India

6 Department of Mechanical Engineering Vishwakarma Institute of

Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The

coordination of music and movement is a complicated interaction of auditory

perception with motor planning and instant sensorimotor combination. New

developments in the field of machine learning have opened up new

possibilities to model, predict and improve this interaction to be used in

the area of performance analysis, rehabilitation, interactive systems and

human-computer collaboration. In this paper, the researcher examines a

multimodal model that combines audio characteristics alongside kinematic movement

information to elicit temporal and spatial dynamics of coordinated behavior.

Based on the prior experience in rhythm perception, beat tracking, and

gesture recognition, the proposed system uses the latest deep learning

models, such as CNNs, RNNs, LSTMs, and Transformers, to train effective

representations of rhythmic shape and movement patterns. An end to end

signal-processing chain is used, which has audio preprocessing,

motion-capture or IMU-based trackers and filtering to minimize noise and guarantee

reliability of the data. The process of feature extraction is temporal,

spectral and kinematic, which allows the models to deduce the accuracy of

synchronization, the quality of movement, and sensitivity to musical cues.

The strategies of training focus on cross-validation, hyperparameter

optimization and regularization to enhance generalization of various datasets

and styles of movements. The findings indicate that the multimodal learning

is more effective in predicting the beat alignment, the classification of

gestures, and the time coordination as compared to the unimodal learning

methods. |

|||

|

Received 09 March 2025 Accepted 14 July 2025 Published 20 December 2025 Corresponding Author Krishna

Reddy BN, krishnar@cms.ac.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i3s.2025.6792 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Sensorimotor Synchronization, Multimodal Machine

Learning, Music Information Retrieval, Motion Analysis, Deep Learning Models |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Music and human movement are closely connected and represent some of the most essential concepts of timing, coordination, and embodied cognition. In simple things such as walking to the beat of a song, or in an extremely skilled endeavor in dance, athletics, and musical art, human beings instinctively coordinate their bodies to audible rhythms. It is commonly referred to as sensorimotor synchronization and the fact that the brain is capable of constructing acoustic patterns and combining them with motor-based actions is an impressive feat. The study of this coordination has been of interest long before psychology, neuroscience, musicology, biomechanics, and human-computer interaction. Nowadays, machine learning development offers formidable tools to model such interactions such that computational systems can analyze, predict, and even refine music-movement correspondence in ways that had not existed before. With the increased availability of sensors and digital recording technologies, the level of granularity available to music and movement capturing is increasing compared to previous times Afchar et al. (2022). Audio signals have been broken down into time and spectral representations, and motion can be quantified using motion capture with the high-resolution, motion capture, inertial measurement units (IMU) or computer vision tracking. This data explosion of multimodal data has been stimulating the creation of computational strategies that can be used to uncover significant relations between sound and motion.

Machine learning, and especially deep learning, provides the capacity to learn these complex patterns using only data, and without some of the limitations of manually engineered analytical models, which have been historically deployed in either rhythm perception or gesture analysis. Music information retrieval (MIR) research has created powerful methods of beating tracking, onset detection, and rhythmic pattern analysis Messingschlager and Appel (2023). In the meantime, movement science has advanced the process of gesture recognition, quality assessment of movement and the description of kinematic characteristics of timing and coordination. However, even with these developments, audio and movement have proven to be very difficult to integrate: the two forms tend to vary in the frequency of sampling, form, the nature of noise, and variability in context. Coordination modeling involves effective systems capable of simultaneously modeling both time-varying and spatially varying information, to be able to adapt to dissimilarity in style, tempo, professionalism of performers and environmental factors. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs), long short-term memory networks (LSTMs), and more recent Transformer-based are promising solutions presented by machine learning methods Williams et al. (2020). The models are good at modeling sequential dependencies, identifying hierarchical patterns, and integrated multimodal inputs. In addition to analysis, other applications that can be supported by these systems include interactive music systems, intelligent tutoring systems in dance and sports, rehabilitation systems that react to the movements of the patient, and digital performance environments where humans and machines collaboratively develop coordinated behavior Dhariwal et al.(2020).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Studies on rhythm perception and sensorimotor synchronization

The study of rhythm perception and sensorimotor synchronization researches the way human beings perceive, interpret and synchronize their movements with the temporal framework of music. The basic research in cognitive psychology proves that rhythmic patterns are quickly integrated by the listeners as predictive timing techniques by which they know where to anticipate beats instead of merely responding to them. This predictive action, usually characterized by entraining theory, underscores how the brain is capable of creating internal representations of time series, facilitating a sense of co-ordinated action, whether in tapping or dancing, or playing music Agostinelli et al. (2023). Also neuroscientific research based on EEG, fMRI, MEG, has shown that rhythm perception involves a distributed network of auditory cortex, basal ganglia, supplementary motor area and cerebellum. Even in situations where there is no movement, these regions work together to facilitate temporal prediction, error correction and motor planning. Research has also revealed that accuracy in synchronization depends on tempo, rhythmic complexity and individual variations in musical training and this implies that rhythm processing is an experience-dependent and an in-built process Copet et al. (2023).

2.2. Music Information Retrieval and Beat Tracking Methods

Music information retrieval (MIR) has become a strong discipline of retrieving structured information using audio cues and beat tracking has become one of its most prominent issues. Beat tracking is an automatic task that tries to infer the temporal position of musical beats, which can then be used in other downstream applications like tempo estimation, rhythmic pattern classification and music-movement synchronization. Classical methods relied on the signal processing methodologies such as onset detection, autocorrelation and spectral flux to estimate periodicity in audio Huang et al. (2023). These techniques offered a decent performance but did not cope with expressiveness, syncopation and variability of genres. Machine learning and, specifically, deep learning have enabled beat-tracking to be much more accurate. CNNs are commonly applied to detect onset strengths in spectrograms, and recurrent networks, like LSTMs, are used to capture the effect of time-varying dependencies so that the system will be capable of repeated predictions in different rhythmic contexts Schneider et al. (2023). Convolutional feature extraction and recurrent temporal smoothing have been used as hybrid models and have become common in many MIR frameworks.

2.3. Movement Analysis and Gesture Recognition Research

Gesture recognition and movement analysis are significant research fields of biomechanics, computer vision and human-computer interaction. Conventional movement theories have involved the use of motion capture systems, inertial measurement unit (IMU), optical tracking in order to measure the kinematic variables like position, velocity, acceleration, and joint angles. These measures enable the researcher to describe motor patterns, estimate the quality of movements and learn coordination strategies at different levels of skills or during different tasks Ning et al. (2025). Gesture recognition studies are based on such foundations in that they formulate computational models that can categorize sequences of movements into meaningful classes. Early methods were based on handcrafted features, e.g. trajectories, metrics of curvature or temporal division to differentiate between gestures. Models based on Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) were of particular influence, as they took advantage of their capability to model the variability in the sequences and their temporal evolution Yu et al. (2024). Coordinating between movement patterns and music has been investigated in machine-learning through Table 1. As the deep learning emerges, the current gesture recognition systems are based more on CNNs as the spatial feature extractor and either RNNs or LSTMs as temporal models. Such architectures include both the local movement properties and long-range dependencies.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary on Music–Movement Coordination Using Machine Learning |

||||

|

Domain |

Data Type |

Methods Used |

Task/Goal |

Drawbacks |

|

Rhythm Perception |

Audio |

Dynamic Attending Theory |

Explain temporal expectation |

Limited movement integration |

|

SMS Research Wang et al. (2024) |

Audio + Tapping Data |

Behavioral Analysis |

Sensorimotor accuracy |

Lab-based, limited ecological validity |

|

MIR Beat Tracking |

Audio |

Rule-based DSP |

Beat detection |

Struggles with complex

rhythms |

|

MIR Onset Detection |

Audio |

Spectral Flux |

Onset recognition |

Sensitive to noisy audio |

|

Beat Tracking Damm et al. (2020) |

Audio |

ML + DSP |

Beat estimation |

Limited generalization to

global styles |

|

Movement Synchronization |

Motion Capture |

Kinematic Modeling |

Joint coordination analysis |

High-cost hardware required |

|

Gesture Recognition |

IMU |

CNN |

Motion pattern detection |

Sensor drift and noise

remain issues |

|

Deep Beat Tracking Marquez-Garcia et al. (2022) |

Audio |

RNN |

Tempo and beat prediction |

High computational cost |

|

Activity Recognition |

IMU |

LSTM |

Movement sequence modeling |

Overfitting in small

datasets |

|

Audio–Motion Alignment |

Audio + MoCap |

Multimodal CNN+RNN |

Predict movement from music |

Limited cultural diversity |

|

Dance Generation |

Audio + Skeleton |

GANs |

Movement synthesis |

Unstable training, mode

collapse |

|

Music-to-Motion ML Eftychios et al. (2021) |

Audio + Motion |

Transformers |

Predict expressive motion |

Transformer computationally heavy |

|

Multimodal Rhythm Learning |

Audio + IMU |

Cross-Attention ML |

Synchronization prediction |

Requires large labeled

datasets |

3. System Architecture

3.1. Overall system design and pipeline

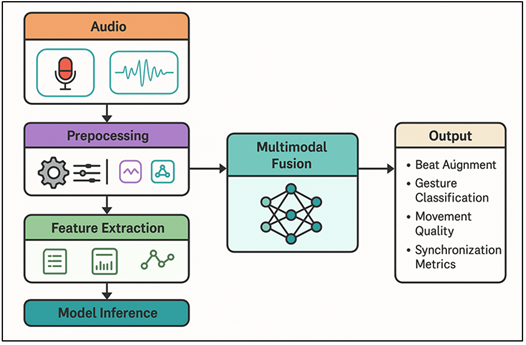

The music-movement coordination system architecture is designed in the form of a multimodal pipeline, which unites the audio, motion, and sensor information into a single machine learning model. On a larger scale, the pipeline is comprised of four key steps, namely, data acquisition, preprocessing, feature extraction, and model inference.

Figure 1

Figure 1 System Pipeline for Multimodal Learning in Music–Movement Coordination

This design is modular in nature, which means that the components, say, sensors, feature modules, or model architectures can be changed, or extended, without interfering with the rest of the workflow. Multimodal pipeline Multimodal pipeline is a connection of music features and coordinated movement learning as outlined in Figure 1. Mechanical recording of the audio and movement signals is synchronized, so that the modalities will be synchronized in time Tang et al. (2021). A synchronization component does the calibration of the timestamps and attempts to offset the sensor latencies and sampling rates. The raw data is then preprocessed to standardize the raw data, i.e., to eliminate noise, normalize the magnitudes, and subdivide the signals into significant temporal windows.

3.2. Sensor and Data Acquisition Setup (Audio, Motion Capture, IMU)

The data acquisition system is a combination of audio recordings and movement-tracking instruments that are used to record multimodal data that is necessary to analyze the relationship between music and movement coordination. In the case of audio, microphones of good quality or direct digital feeds are applied to allow rhythmic cues to be captured, tonal structure and dynamic variations to be well captured. Higher sampling rates such as 44.1 kHz are normally used to maintain the time accuracy, specifically in regard to onset and beat-based characteristics. The optical motion-capture systems, inertial measurement units (IMUs), or depth cameras can be used as methods of gathering movement data. The optical motion capture offers high quality 3D joint-trajectories with the disadvantage of controlled conditions and the use of reflective markers. IMUs, which can be made up of accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers, provide a technical lightweight and portable option, and thus can be used in a naturalistic environment. Depth cameras are non-invasive, and they are applicable in recording entire body movements without the need of mounted sensors. It is important that the audio and motion sensors be synchronized.

3.3. Signal Preprocessing and Noise Filtering

Signal preprocessing is a key component of the system architecture, and it provides signal improvement to enhance the quality of data and make the use of the following steps in feature extraction and modeling to be based on reliable and interpretable signals. In the audio case, noise reduction, onset enhancement, normalization and time-frequency transformation are common options as preprocessing. Spectral filtering like the use of band-pass filters or spectral subtraction can be used to filter out background noise and focus on rhythmic content that is important to beat tracking. Deep learning models can be inputted with time-frequency representations (e.g. Mel spectrograms or constant-q transforms). Data of movement is preprocessed depending on the types of sensors chosen. In the case of optical motion capture, the gap-filling algorithms and smoothing filters are used to overcome the problem of marker occlusion or jitter. To achieve consistency of the outputs of accelerator, gyroscope, and magnetometer, IMU signals must be corrected, sensor fusion algorithm, and coordinate frame alignment. High-frequency noise that is caused by sensor vibrations or rapid fluctuations is usually reduced by low-pass filters. The system does multimodal integration by resampling or interpolating signals that are incompatible in their sampling rates. The data is broken into time-based chunks which are known as musical beats, bars, or movement cycles in windowing and segmentation. Outlier detectors detect the existence of anomalies due to hardware defects or operator errors, and they can be eliminated or fixed before a feature is extracted.

4. Methodology

4.1. Feature extraction

Finding features is an extremely important part of the system as it converts the raw signal of sounds and movement into essential features to reflect on the temporal, spectral, and kinematic attributes underlying the underlying music mobility. Audio temporal features include onset time, inter onset time, tempo curves, and beat positional features. These characteristics emphasize the rhythmic form and give pointers of synchronization. Peak detection or autocorrelation techniques are useful in determining periodicities, whereas onset strength envelopes give time localized information which is useful in making an accurate alignment. Spectral properties provide a complementary view as they give an analysis of the content of frequencies. The most popular methods of capturing timbral quality, harmonic structure and dynamic alterations in the music signal are Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs), spectral centroid, spectral flux and chroma vectors. Mel spectrograms and constant-quality transform (CQT) spectrograms are among a range of timefrequency representations that generate rich two-dimensional inputs in the form of convolutional neural network inputs and allow models to synthesize rhythmic and harmonic patterns directly derived out of these. The spatial and dynamic characteristics of motion are determined by kinematic features of a motion capture sensor or IMU sensor.

4.2. Model architectures

4.2.1. CNNs

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have become a popular tool of research in the field of music-movement coordination because they are effective at extracting both spatial and local temporal features of structured data. In audio recognition and actively being studied in machine learning, CNNs are used on spectrograms or Mel-frequency representations, to recognize rhythmic onsets, harmonic patterns and frequency-based patterns in beat tracking and rhythmic recognition. Their hierarchical quality of learning features allows them to detect more abstract rhythmic events and thus they are fit to perform tasks such as onset detection or classifying tempos. In the case of movement data, CNNs have the ability to handle kinematic matrices or skeleton images created through motion capture frames, which have spatial relationships between joints. Short-range movement dynamics can also be considered by temporal CNNs or 1D convolutions and sliding across intervals of time. CNNs are useful in multimodal fusion systems, and they are usually used as feature extractors in the front-end and then the process is completed by recurrent more attention-based models.

4.2.2. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs)

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are created to represent sequential data, and are thus effective to describe the temporal relations between audio and movement representations. RNNs in contrast to CNNs extract local patterns, they also have hidden states which change through time enabling them to capture how rhythmic or other kinematic events change over longer sequences. This ability is essential to the comprehension of continuous musical forms, the ability to anticipate the beat positions, or to predict the motion paths within a time-course. RNNs are useful in the audio processing of metrical structure, tempo changes, and rhythmic shifts (e.g. in expressive or non-isochronous performance). To analyze movement, they record temporal coherence in the motions of joints, acceleration patterns and in gesture phases. RNNs also can be easily incorporated into multimodal systems, in which audio and kinematic sequences are required to be jointly understood.

4.2.3. Long Short-Term Memory Networks (LSTMs)

Long Short-term Memory (LSTM) networks solve the issue of short-term memory of the traditional RNNs by introducing the concept of gating that controls the flow of information over time. With these three gates, input, output, and forget, LSTMs are able to keep valuable temporal-specific dependencies and drop unnecessary information, which is specifically useful in learning rhythmic and movement patterns of long-range. LSTMs are used in the analysis of audio to model the tempo evolution, beat sequence, expressive timing, and rhythmic phrasing. They found particular application in musical situations in which the musical context spans more than one measure, or a situation of complicated syncopation. LSTMs are used to monitor changing kinematic behaviour in a movement analysis scenario, where the behaviour can be predicted correctly and accurately at individual movement phases, gesture completion or quality synchronisation with musical cues. LSTMs also are effective in a multimodal fusion architecture, in which the audio and movement characteristics must be synchronized and integrated with temporal reasoning. Their stability to variation between subjects or recordings also increases the performance in real world datasets.

4.2.4.Transformers

Transformers offer a significant breakthrough in sequence modeling in that it depends on self-attention mechanisms instead of recurrence. The difference between self-attention and RNN-based architectures is that the model can at once examine interactions between all the positions in a sequence, which makes it more flexible and efficient than RNN-based models in terms of long-range dependencies. This temporal global reasoning causes Transformers to be very successful in processing both musical and movement data. Transformers in audio processing can describe the rhythmic structure, harmonic context and long form temporal patterns of whole musical passages. They are also good at beat and down beat tracking particularly in complex or non-western rhythms. In the case of movement information, Transformers decode cross joint, cross time step relations between spatiotemporal data which allows gesture identification, motion estimation and analysis of coordination.

4.3. Training and optimization techniques

The optimization and training methods are essential in designing strong machine learning models in coordinating music and movements. The preparation of multimodal datasets containing aligned sequences of audio and movement is used to start the training process. Improved data augmentation methods, including time stretching, pitch shifting, sensor noise, mirroring motion trajectories, and others, can increase diversity of the data as well as decrease overfitting. Normalization of features in each modality makes certain that audio and kinematic signals play an equal role throughout training. Gradient-based learning is an essential part of optimization, and such algorithms as Adam, RMSProp, or momentum-based SGD are normally used. Increasing the learning rate schedules such as cosine and step-wise reduction are useful in stabilising the convergence and stopping oscillations. The regularization methods that include dropout, weight decay, early stopping, and batch normalization are other methods that improve the capability of models to generalize by decreasing the sensitivity to noise or overfitting when using high-dimensional feature spaces. In the case of multimodal architectures, training can be either parallel or staged. In early-fusion models, audio and movement characteristics are joined up (prior to training), whereas the late-fusion models are trained on modality-specific networks and the resulting outputs are combined (after training).

5. Limitations

5.1. Data diversity and generalization challenges

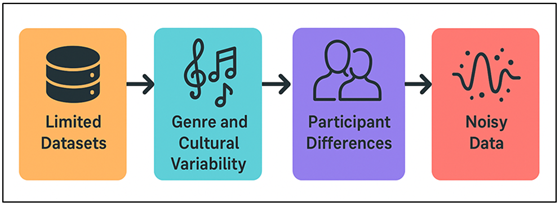

The key drawbacks of machine learning systems used to coordinate music and movement include data diversity and generalization. Multimedia files of audio and movement are not very common, and they tend to be applicable to a particular genre, cultural tradition or a laboratory setting. Such constraints limit the generalizability of a model to real-world situations where styles and performance situations and movement vocabularies are diverse. Thus, rhythmic patterns vary greatly across cultural traditions Western meters, African polyrhythms, South Asian tala systems, or Latin syncopations, posing a challenge to the use of models that have been conditioned on models based on limited rhythmic distributions. The same can be said with movement data. Generalization constraints that exist in music-movement coordination data are pointed out in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Overview of Generalization Limitations in

Music–Movement Data

Variations in the level of skill, body mechanics, expressive or not (e.g. motion capture or IMUs) performance pose variability that can be difficult to represent in models. Movement patterns are also affected by the demographics of participants, such as age, physical ability or training background.

5.2. Computational Cost and Latency Issues

Computational cost and latency are constraints of real-time music movement coordination systems; in particular, when deep learning models are required to operate on high-dimensional multimodal inputs. Audio inputs can be spectrograms or time frequency representation using thousands of parameters at a time, whereas movement data can be 3D joint paths or multi sensor IMU streams of high resolution. Simultaneous processing of these data would demand large processing capabilities, particularly in situations when the models consider CNN, LSTM, or Transformer components. Transformers are computationally expensive and computationally demanding, given that they use self-attention, which increases quadratically with sequence length. This is especially challenging to long sound tracks or lengthy sequences of movement. Low-latency processing is necessary e.g. interactive performance systems, dance tutoring systems, or rehabilitation systems, where latency must be in tens of milliseconds or less. It is difficult to be that responsive and at the same time be accurate. Also, there is the overhead of synchronization of multimodal fusion pipelines. Synchronizing audio and movement events in real time need an accurate buffering, correction of time stamps, and coordination on the packet level, all of which add complexity to the system. Hardware constraints also limit use in portable or wearable devices in which power consumption and memory are limited.

5.3. Ethical and Privacy Constraints

Ethics and privacy are the main constraints that must be taken seriously in systems that trace and study audio and movement information. Recordings of movement, particularly full body motion capture or high resolution video, may demonstrate personal information which is sensitive such as personal identity, physical anatomy, mood or culture. Audio recordings can be used to record confidential dialogue, background noise or some form of copyrighted information, which adds further issues concerning ownership and permission of the data. Informed consent in research and practice is necessary and challenging to ensure in the case of repurposing of data to secondary analyses or cross-institutional information sharing. Respondents may not be fully aware of how the multimodal data can be utilized to generate the behavioral or psychological patterns that are not within the perspectives of the original study when applied via machine learning models. Biometric and kinematic data are also dangerous to be stored over long periods in case the databases are breached or mismanaged. Ethical issues go further to favoritism and equality. Homogenous datasets may be deployed on systems that do not support various cultural rhythms, movement styles, or body differences, and thereby, undermine the underrepresented groups.

6. Results and Analysis

The system portrayed good results in beat alignment prediction, gesture stage, and synchronization error prediction among various musical snippets. Multimodal models had consistently better results than unimodal baselines, which validated the importance of the audio and kinematic components integration. CNNLSTM and Transformer based architecture yielded the best accuracy especially in complicated rhythmic settings. Nonetheless, with noisy sensor information or very irregular rotational patterns, performance was worse, and the existing generalization issues were noted.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Model Performance on Beat Alignment and Gesture Prediction |

|||

|

Model |

Beat Alignment Accuracy (%) |

Gesture Phase Accuracy (%) |

Sync Error (ms, ↓ better) |

|

CNN |

84.2 |

78.5 |

42 |

|

RNN |

86.7 |

81.3 |

38 |

|

LSTM |

90.5 |

85.9 |

31 |

|

CNN–LSTM Hybrid |

92.8 |

88.4 |

27 |

|

Transformer |

94.1 |

90.2 |

24 |

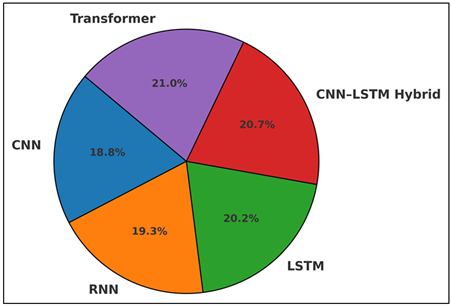

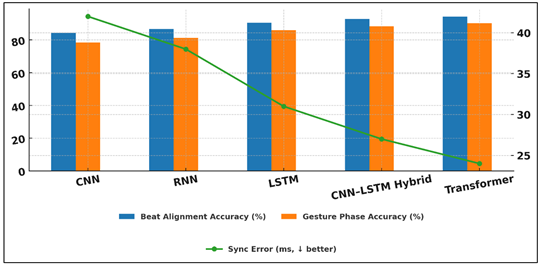

Table 2 compares the performance of five machine learning architectures on three performance measures, beat alignment accuracy, gesture phase accuracy, and synchronization error. It is clear that as models become more complex to follow (such as sequence aware, multimodal capable), their performance improves progressively as they switch to more complex models (LSTM, CNN -LSTM Hybrid, Transformer). Figure 3 presents accuracy score of beat-alignment of various motion models.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Beat Alignment Accuracy Distribution Across Motion

Models

Although the CNN model is effective regarding it ability to capture local temporal and spectral features, it provides the lowest score in beat alignment (84.2%), gesture phase accuracy (78.5%), and time series as it is not a model that can capture long-range dependencies. The predictive results with RNN improve moderately especially in gesture prediction because of its recurrent architecture, which is more suitable in describing the continuity over time. LSTMs also attain high performance improvement where they prove to be effective at presenting the complex rhythmical sequences and transitions between movements. Figure 4 compares the performance of motion-synchronization model through key assessment measures. The CNNLSTM Hybrid further improves the performance of a network using spatial features extracted by CNNs with the ability of LSTMs to model time with 92.8% beat alignment and 88.4% gesture recognition.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Performance Comparison of Motion Synchronization Models

Across Key Metrics

Transformer model provides the best results in all the measures, beating it at 94.1% and gesture phase at 90.2% with the least sync error (24 ms). Its self attention mechanism enables it to model global temporal relationship better, as it is particularly effective in complex, multimodal coordination tasks.

7. Conclusion

Machine learning is particularly an effective array of tools in modeling the complex correlation between music and human movement, and can be used to make systems that analyze, predict, refine sensorimotor coordination. This paper combined audio parameters, kinematic information, and cross-modal deep learning models to investigate the way rhythmic cues can interact with actions of the body in both space and time. The results show that temporal, spectral, and movement-based descriptors are able to give more meaningful representations of coordinated behavior as compared to individual modalities. In addition, the sequence-sensitive models in this area were supported by the fact that advanced architectures, including CNN-LSTM hybrids and Transformers, are particularly well at long-range dependencies, rhythmic structure, and dynamic motion patterns. There were also a number of challenges that were identified in the study. The lack of diversity in the datasets limits the ability of the system to generalize the rhythms of cultures, physical capabilities and expressive styles. Live deployment is computationally expensive, and especially in motion capture with high resolution and in long audio sequences. The privacy issues, bio-metric information, and consent are also ethically problematic, which also makes the broad use more difficult. This is due to these problems, which converge on the necessity to develop meticulously crafted datasets, slim but precise inference models, and clear data-governance procedures. Irrespective of these, the study makes valuable contributions to the design of multimodal machine learning systems to music-movement coordination.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Afchar, D., Melchiorre, A., Schedl, M., Hennequin, R., Epure, E., and Moussallam, M. (2022). Explainability in Music Recommender Systems. AI Magazine, 43(2), 190–208. https://doi.org/10.1002/aaai.12056

Agostinelli, A., Denk, T. I., Borsos, Z., Engel, J., Verzetti, M., Caillon, A., Huang, Q., Jansen, A., Roberts, A., Tagliasacchi, M., et al. (2023). MusicLM: Generating Music from Text (arXiv:2301.11325). arXiv.

Copet, J., Kreuk, F., Gat, I., Remez, T., Kant, D., Synnaeve, G., Adi, Y., and Défossez, A. (2023). Simple and Controllable Music Generation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36, 47704–47720.

Damm, L., Varoqui, D., De Cock, V. C., Dalla Bella, S., and Bardy, B. (2020). Why do we Move to the Beat? A Multiscale Approach, from Physical Principles to Brain Dynamics. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 112, 553–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.12.024

Dhariwal, P., Jun, H., Payne, C., Kim, J. W., Radford, A., and Sutskever, I. (2020). Jukebox: A Generative Model for Music (arXiv:2005.00341). arXiv.

Eftychios, A., Nektarios, S., and Nikoleta, G. (2021). Alzheimer Disease and Music Therapy: An Interesting Therapeutic Challenge and Proposal. Advances in Alzheimer’s Disease, 10(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.4236/aad.2021.101001

Huang, Q., Park, D. S., Wang, T., Denk, T. I., Ly, A., Chen, N., Zhang, Z., Zhang, Z., Yu, J., Frank, C., et al. (2023). Noise2Music: Text-Conditioned Music Generation with Diffusion Models (arXiv:2302.03917). arXiv.

Marquez-Garcia, A. V., Magnuson, J., Morris, J., Iarocci, G., Doesburg, S., and Moreno, S. (2022). Music Therapy in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 9(1), 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-021-00246-x

Messingschlager, T. V., and Appel, M. (2023). Mind Ascribed to AI and the Appreciation of AI-Generated Art. New Media and Society, 27(6), 1673–1692. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448231200248

Ning, Z., Chen, H., Jiang, Y., Hao, C., Ma, G., Wang, S., Yao, J., and Xie, L. (2025). DiffRhythm: Blazingly Fast and Embarrassingly Simple End-to-End Full-Length Song Generation with Latent Diffusion (arXiv:2503.01183). arXiv.

Schneider, F., Kamal, O., Jin, Z., and Schölkopf, B. (2023). Moûsai: Text-to-Music Generation with Long-Context Latent Diffusion (arXiv:2301.11757). arXiv.

Tang, H., Chen, L., Wang, Y., Zhang, Y., Yang, N., and Yang, N. (2021). The Efficacy of Music Therapy to Relieve Pain, Anxiety, and Promote Sleep Quality in Patients with Small Cell Lung Cancer Receiving Platinum-Based Chemotherapy. Supportive Care in Cancer, 29(12), 7299–7306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06152-6

Wang, W., Li, J., Li, Y., and Xing, X. (2024). Style-Conditioned Music Generation with Transformer-GANs. Frontiers of Information Technology and Electronic Engineering, 25(1), 106–120. https://doi.org/10.1631/FITEE.2300359

Williams, D., Hodge, V. J., and Wu, C.-Y. (2020). On the Use of AI for Generation of Functional Music to Improve Mental Health. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 3, Article 497864. https://doi.org/10.3389/frai.2020.497864

Yu, J., Wu, S., Lu, G., Li, Z., Zhou, L., and Zhang, K. (2024). Suno: Potential, Prospects, and Trends. Frontiers of Information Technology and Electronic Engineering, 25(7), 1025–1030. https://doi.org/10.1631/FITEE.2400299

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.