ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Smart Materials in Sculptural Education

Sorabh Sharma 1![]()

![]() ,

B. Dhanalakshmi 2

,

B. Dhanalakshmi 2![]()

![]() , Shankar

Prasad S 3

, Shankar

Prasad S 3![]()

![]() , Mohit

Malik 4

, Mohit

Malik 4![]() , Kajal

Thakuriya 5

, Kajal

Thakuriya 5![]()

![]() , Mohit

Gupta 6

, Mohit

Gupta 6![]()

![]() , Pawan

Wawage 7

, Pawan

Wawage 7![]()

![]()

1 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

2 Department

of Humanities and Science, Aarupadai Veedu Institute of Technology, Vinayaka

Mission’s Research Foundation (DU), Tamil Nadu, India

3 Associate Professor, Department of Management Studies, JAIN

(Deemed-to-be University), Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

4 Assistant Professor, School of Business Management, Noida International

University 203201, India

5 HOD, Professor, Department of Design, Vivekananda Global University,

Jaipur, India

6 Chitkara Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University,

Himachal Pradesh, Solan, 174103, India

7 Assistant Professor, Department of Information Technology, Vishwakarma

Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The

introduction of intelligent materials in sculpture education is reshaping the

ancient ways of providing art-making with dynamism in ability to react, deal,

and sensitivity to the environment. In the present paper, the mechanisms of

enhancing the expressive and functional possibilities of the sculpture at

hand through the use of shape memory alloys and polymers, piezoelectric

composites, and chromic substances are discussed. The paper examines their

characteristics like actuation and self-modification, color-shift behavior,

etc and the way these materials reconfigure the adaptive, kinetic and

interactive artworks. This study extends to the field of education where

interdisciplinary education is encouraged through the application of smart

materials where material science, engineering, and digital fabrication are

combined with artistic implementation. The study assesses the pedagogical

value of integrating these new technologies through qualitative case studies,

experimentation in the studio and examination of student initiated projects.

Results indicate that smart materials promote innovation, creative

problem-solving, and creativity as well as sustainable and responsive art

practices. Nevertheless, there are still some difficulties, especially when

it comes to material availability, price, technical restrictions, and the

necessary expertise. In spite of these limitations, the study shows that

purposeful curriculum development and practical exploration can be successful

in facilitating the implementation of smart materials in the sculpture

courses. Altogether, the present work emphasizes the importance of

introducing smart materials into the art education process as the method of

deepening the experiential learning practice and broadening the conceptual

and practical boundaries of the sculptural practice. |

|||

|

Received 16 March 2025 Accepted 21 July 2025 Published 20 December 2025 Corresponding Author Sorabh

Sharma, sorabh.sharma.orp@chitkara.edu.in

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i3s.2025.6785 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Smart Materials, Sculptural Education, Kinetic Art,

Material Innovation, Interactive Sculpture, Interdisciplinary Pedagogy |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The development of the sculptural practice was, and will be always, directly connected with the improvement of the material technologies. Since the first sculptures were made using stone, clay, and bronze, every new material has increased the scope of expression and conceptualization of sculpture. However, the recent development of smart materials, materials that can sense, react to or change to the outside environment, has presented a whole new frontier to artists and educators alike. These materials consist of shape memory alloys, responsive polymers, piezoelectric composite and chromic pigment, and push the traditional concepts of a stable form to the sculptural vocabulary - these materials incorporate movement, interactivity, and environmental sensitivity. The smart materials are therefore not additions to the toolkit of an artist; they are a paradigm shift of how sculptural objects can act, communicate and engage with their environment. This change is both an opportunity and task within the context of the educational setting Guo et al. (2025). Art and design school programs are increasingly being challenged to prepare students to operate in the rapidly shifting creative landscape, in which the ability to be technologically literate and work interdisciplinarily has become the main determinants of success, along with the crafts and aesthetic training. The integration is a dedicated platform that is sought after using intelligent materials, and students can acquire knowledge on how the arts, science, engineering, and digital systems interact Stamkou et al. (2022). An experience with materials that respond to heat, light, pressure, electricity, or magnetic fields assist in motivating students not merely to consider the physical attributes of the work they are developing, but to consider also the dynamic interaction between the work and the viewers and spaces. This promotes a more systems-based comprehensive appreciation of sculpture that also conforms to the current artistic and social issues Serrao et al. (2024).

Introduction of the smart materials in the sculptural education also serves the broader pedagogical intentions. Such materials are biased toward experiential learning since they demand the experimentation, the ability to test and also the ability to reflect critically on the lessons learned-skills that form the core of the studio-based practice. They encourage creative problem-solving because students struggle with aesthetic and technical problems: how to fit sensors in, how to choreograph movement, how to keep the system functioning, and how to combine the arts and crafts of the analog with the digital, such as 3D printing or microcontroller programming Petti et al. (2020). Although such materials present transformative opportunities, they are more expensive, demand specialized skills and can add complexities that can discourage students and instructors who are not used to technological media Zhang et al. (2022). To solve these issues, curriculum development must be designed carefully, academic collaborations should be established, and the new material practices should be supported by the institution.

2. Background Work

The integration of intelligent materials into the artistic and educational sphere has long been a process that has unfolded over the last few decades, a by-product of the parallelism of progress in the material sciences, engineering, and the art of the present-day. The First Contemporary work can be dated to the middle of the 20 th century, when scientists started to investigate materials capable of self-changing shape, producing a signal, or changing physical characteristics based on environmental factors. Nitinol discovered in the 1960s as shape memory alloys and electroactive polymers discovered later offered the scientific basis of materials with reversible transformation Ding et al. (2021). With the maturation of these technologies, artists began to have interest in experimenting with motion, responsiveness, and sense perception in the forms of sculpture. Kinetic and interactive practices established some significant conceptual bases in the art world. Movement and interactivity were brought forth by artists like Alexander Calder, Jean Tinguely and subsequently by Rebecca Horn, long before smart materials were easily accessible Liu et al. (2021). Their work created a format of thinking sculpture as a living system not as an object. Creating sensors, microcontrollers and electromechanical parts, artists and designers began experimenting with them at the end of the 20 th and beginning of the 21 st centuries and continued to further expand the gulf between technological innovation and creativity Oladele et al. (2020). These interdisciplinary projects provided foundations of the incorporation of smart materials in creative disciplines, which prove to be applicable not just in technical applications. The idea of smart materials has been given traction within the field of sculptural education as the use of hybrid practices and STEAM-related approaches gain more importance in art schools Peng et al. (2021). Research techniques, contributions and benefits of smart-material in sculpture are summed up in Table 1. Despite its relative novelty, it is this body of background that represents the increasing awareness of smart materials as an artistic medium, as well as a means of teaching and learning, which is defining the changing state in contemporary sculpture.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Overview of Research Contributions, Methods, and Advantages in Smart Material Applications for Sculpture |

|||||

|

Focus Area |

Smart Material Type |

Methodology |

Educational Setting |

Outcome Measured |

Advantages |

|

Interactive sculpture using responsive materials Du (2022) |

Piezoelectric films |

Case study |

University studio course |

Student engagement |

Encourages sensory learning |

|

Kinetic art integration |

Shape memory alloys |

Experimental prototypes |

Advanced sculpture class |

Motion accuracy |

Lightweight, silent motion |

|

Chromic materials in public art |

Thermochromic pigments |

Field testing |

Outdoor installation workshop |

Environmental response |

Passive energy use |

|

STEAM curriculum development |

Mixed smart materials |

Curriculum design |

High school art-tech program |

Learning outcomes |

Bridges art & science |

|

Digital fabrication with SMPs |

Shape memory polymers |

3D printing trials |

Fab-lab environment |

Fabrication success rate |

Easy molding & reprogramming |

|

Sensory installations Shi et al. (2021) |

Piezo sensors |

User interaction study |

Museum education program |

Audience response |

Enables real-time feedback |

|

Smart textiles in sculpture |

Thermochromic textiles |

Material testing |

Textile-art hybrid course |

Material flexibility |

Highly adaptable surfaces |

|

Environmental data sculptures |

Photochromic materials |

Outdoor exposure tests |

Environmental art seminar |

Data visualization |

No electronic power needed |

|

Kinetic transformation studies Xu (2020) |

SMAs + microcontrollers |

Lab experiments |

Engineering–art collaboration |

Motion precision |

Offers mechanical elegance |

|

Student prototyping behaviour |

Mixed smart materials |

Qualitative analysis |

Introductory sculpture class |

Prototyping success |

High creative exploration |

|

Sustainable smart materials use |

Biodegradable polymers |

Life-cycle assessment |

Green design studio |

Environmental impact |

Eco-friendly options |

3. Types and Properties of Smart Materials

3.1. Shape memory alloys and polymers

Some of the most common smart materials in sculptural application are shape memory alloys (SMAs) and shape memory polymers (SMPs) because they can experience reversible transformations. Nitinol, a shape memory alloy, has a special ability, which is the shape memory effect, wherein the alloy may recover a previously defined form, when subjected to heat or electrical current. Figure 1 represents the mechanisms and classification categories of shape memory materials.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Mechanism and Classification of Shape Memory

Materials

This act enables artists to make sculptures which are bent, twisted or folded down in a controlled and repeatable manner. Superelasticity also occurs in SMAs and allows them to take up large amounts of deformation without irreversible damage, which is a desirable quality in an interactive artwork that encourages touching. Shape memory polymers work on the same principle however they are different structurally and mechanically Yu et al. (2018). SMPs are not as heavy as metals, are flexible and can be dramatically deformed. They tend to be changed by changes in temperature, but more light- and moisture-sensitive versions have been produced. SMPs are easy to shape into intricate shapes with the help of available tools of fabrication like 3D printers, which makes them especially attractive in classroom settings. The fact that they can do so in recalling and revisiting programmed geometries gives students an intuition of what material responsiveness is like Zhao et al. (2020).

3.2. Piezoelectric Materials

The piezoelectric materials have the capability of transforming the mechanical stress into electrical energy and the opposite of this as well. This bi-directional nature makes them especially interesting when it comes to sculptural use based on sensitivity, interactivity as well as delicate movement. Examples of common piezoelectric materials are quartz crystal, ceramic (PZT, lead zirconate titanate), and more recent piezoelectric films made of polymer Zhang et al. (2022). These materials applied to sculpture have the capability of making vibrating surfaces, responsive surfaces or making signals depending on conditions in the surrounding, like pressure, touch, or vibration. Piezoelectric materials in the educational world offer students an available point of introduction to the electromechanical systems. They can do this because the relatively straightforward wiring needs enable the learners to experiment with touch-reactive surfaces, sound-driven installations, or self-powered sensors without sophisticated engineering abilities Liu et al. (2022). The piezo films and discs may be incorporated into sculptural structures in order to respond to movement or create motion to allow artwork to engage with the audiences. One such example could be a sculpture that produces sound when played with or slightly changes shape in a reaction to the vibrations in the environment around. Piezoelectric actuators have more possibilities of kinetic expression. They can bend, contract, or oscillate when stimulated electrically giving artists the opportunity to produce delicate rhythmic motions. These properties make piezoelectric materials useful in the study of the links between energy, environment and form Shi et al. (2021).

4. Application of Smart Materials in Sculpture

4.1. Adaptive and kinetic sculptures

Adaptive and kinetic sculpture is one of the most exciting ways of utilizing smart materials wherein the artists can produce pieces that move, change, and react to the environment. Kinetic art was traditionally based on the mechanical mechanism (motor or gears, or some other source of force). The repertoire of Smart materials, especially, shape memory alloys, electroactive polymers and piezoelectric actuators is extended to include movement that is a consequence of the inherent behavior of the material. These adaptable components enable the sculptor to create the form that becomes bent, twisted, unfolded or vibrated without the huge mechanical constructions, which creates a more flowing, organic and integrated movement Venkataramanaiah et al. (2021). Adaptive sculptures go beyond this with their configuration changing upon being exposed to external stimuli (heat, light, pressure, electrical signal) or changing with a response. An illustration of this is a sculpture that has shape memory alloys embedded in it; it will change shape during the day due to the different ambient temperatures and thermochromic materials can cause slight color changes that reflect the conditions around the work. This real-time transformational ability places smart materials as agents of changes and information, which allows artworks to reflect transformations due to cycles and environmental consciousness.

4.2. Interactive Installations and Sensory Art

Smart materials enhance interactive installations and sensory art a lot because they allow works of art to react to the presence, touch, sound, or environmental changes of humans directly. The fact that they are capable of sensing and responding facilitates them to be the best at creating immersive experience where participation by the audience becomes a part of the work. Touch, vibration or light exposure can be detected by piezoelectric sensors, thermochromic pigments and photochromic films and used as inputs to produce visual, audio or kinetic output. The interactive possibility enables the sculptors to make works which can also communicate with the viewers and change form or color according to behavioral features in human beings or surrounding conditions. An example of this is an installation that requires the use of piezoelectric elements, so that when someone walks over it, the installation responds, or an installation made of thermochromic surfaces that draw new images as one touches them. Photochromic substances have the capacity to produce dynamic space systems that change over the day depending on the changing sunlight. These interactions are invitations to the viewers to join them as co-creators breaking down the conventional distinctions between artwork and viewers. The educational process is in the field of smart materials, which promotes the comprehension of the sense perception, interactiveness and the interactions between human and surroundings better.

4.3. Integration of Smart Materials with Digital Fabrication

The integration of intelligent materials and digital fabrication technologies offers new opportunities of creating sensitive sculptures in association with superb production. The 3D printing, CNC milling and laser cutting tools allow the artist to create complicated geometries, bespoke housings and bespoke interfaces to accommodate the behavioral idiosyncrasy of smart materials. Examples are, but not limited to, 3D printing shape memory polymers into complex structures that are programmed to deform in a particular way and piezoelectric components which can be digitally designed in components to sense or to act. Digital fabrication increases the ease of access and reuse of smart materials providing students and artists with the capability to prototype inexpensively and refine designs through reuse. The computational design software combined with responsive materials further promotes the creation of hybrid sculptures which further erases the lines between physical appearance and digital logic. The parametric modeling tools enable the creators to simulate the material behavior, structural performance optimization and interactions, prior to the commencement of fabrication. This integration is used in sculptural education as a means of a STEAM-approach to learning, where students are expected to combine a sense of artistic insight and engineering principles.

5. Pedagogical Implications in Sculptural Education

5.1. Curriculum innovation and interdisciplinary approaches

To implement smart materials in sculptural studies, curriculum innovation of significance must be adopted to adopt interdisciplinary learning. As the sphere of sculpture and the sphere of material science are becoming increasingly interdependent, engineering and computer technologies, the traditional art circulation must be inclined to the practice of teaching the ability and knowledge which will allow them to be able to exercise contemporary creativity. It does not simply consist of the mere insertion of separate and distinct courses in technical disciplines but a restructuring of the curriculum into a living and cross-disciplinary system where artistic investigation and scientific knowledge exist alongside each other. The integration of the issues of responsive material behavior, embedded electronics, and computational design will assist the students in thinking out of the box and learn about sculpture as a type of interactive and living science. Figure 2 describes a model that can help to modernize the curriculum and provide a lot of cross-disciplinary learning experience. The multi-disciplinary method also encourages interdepartmental collaboration among the disciplines (e.g. art, engineering, and architecture and computer science) and thus the creative capabilities accessible to the students.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Framework for Curriculum Innovation and

Interdisciplinary Learning

Through joint workshops, co-taught courses and collaborative studio projects learners have a chance to experiment with smart materials in a variety of ways, and their comprehension of artistic and technical aspects is enhanced.

5.2. Studio-Based Experimentation with Material Technologies

The experimentation in the studio is one of the pillars of sculptural education, and working with smart materials will also enrich this experience, encouraging risk-taking, learning by doing, and iterating. In contrast to conventional materials, smart materials have the students to work with physical processes that make them come into direct contact with stimuli (heat, light, pressure, electricity). This interactive learning stimulates the learners to explore the aesthetic features of materials as well as their functional and behavioral characteristics.

5.3. Challenges in Accessibility, Cost, and Sustainability

Numerous smart materials, which include shape memory alloys, advanced polymers, and piezoelectric components, are not cheap when compared to the traditional sculptural media. This may be constrained in their cost because students may not access them, or may have restricted scale or frequency of experimentation. There might be a difficulty in institutions in providing funds to purchase materials, service equipment or upgrade digital fabrication facilities that would be needed to operate with these technologies. Accessibility is not limited to monetary factors. Smart materials may involve semi-technical skills, equipment and safety measures which may pose obstacles to students who might not be well versed with the concepts of electronics or engineering. Lack of proper instructions and support can make the learners feel overwhelmed or disheartened and this might increase the skills gaps in the classroom. Teachers, therefore, have to devise ways of scaffolding knowledge, offering entry points that are easy to access, and making sure students (with or without a technical background) can get significant engagement with such materials. Sustainability is also a matter of concern.

6. Results and Discussion

The paper found out that smart materials greatly enriched sculptural education, as it provided creative thinking, interdisciplinary thinking, and experimental learning. Students were more engaged when dealing with responsive materials, creating pieces of art reflecting motion, interaction and environmental sensitivity. Educators testified to a higher level of problem-solving and the increased readiness of students to use new technologies. Nevertheless, material cost, technical complexity and inaccessibility to specialized tools were all challenges that affected the extent of experimentation.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Student Engagement and Learning Outcomes Using Smart Materials |

||

|

Metric |

Before Integration |

After Integration |

|

Student engagement level (%) |

52 |

87 |

|

Creativity score in project evaluation (%) |

61 |

89 |

|

Successful project completion rate (%) |

72 |

91 |

|

Interdisciplinary collaboration instances |

14 |

28 |

|

Use of experimental materials per student |

1.3 |

3.6 |

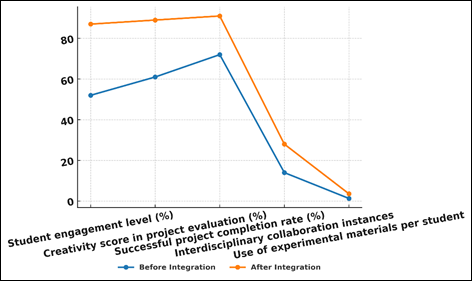

The statistics provided in Table 2 show that there is a definite positive influence of smart materials introduction in the sculptural education. The level of student engagement was significantly raised as the percentage of engagement grew by 52 to 87, which shows that interactive processes and responsive materials raised the levels of interest and engagement significantly. Figure 3 indicates performance improvement after the introduction of AI in education.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Performance Improvement

Before and After AI Integration in Educatio

This change implies that smart materials provide new concrete learning processes that are appealing to students. The creativity scores also increased by 61 percent to 89 percent in terms of increased imaginative exploration and wide concept range in the projects of students.

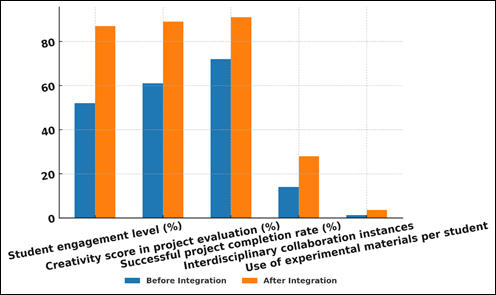

Figure 4

Figure 4 Comparative Analysis of Educational Metrics Pre- and

Post-AI Integration

The non-stagnant and non-reliable quality of smart materials must have prompted the learners to be more experimental and think of new artistic solutions. The comparison of the educational metrics of the pre-implementation stage and the post-implementation stage is presented in Figure 4. The rates of successful project completion went up (72 to 91), and it can be concluded that the students did not only work more intensively, but were also capable of implementing their ideas more confidently and competently. The number of interdisciplinary cooperation increased almost two times: 14 to 28 cases, which depict how smart materials may be used to achieve cross-departmental interaction between the art, engineering, and technology disciplines.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Challenges Encountered During Smart Material Integration |

||

|

Challenge

Category |

Frequency

Reported (n) |

Percentage

(%) |

|

High material cost |

22 |

31% |

|

Technical complexity |

29 |

41% |

|

Limited tool/resources

access |

18 |

26% |

|

Material durability issues |

12 |

17% |

|

Sustainability concerns |

9 |

13% |

The difficulties of applying smart materials to sculptural education are outlined in Table 3 and include a number of obstacles to the education process by educators and students. Technical complexity is the most reported problem with 29 responses (41%). This means that a lot of intelligent material involves specific skills and needs to be handled very carefully and that learning about the use of electronics or programming, which may scare away learners not used to these technologies.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Reported Challenges and Their Frequency in AI–Assisted Creative Projects

The solution to this barrier is to conduct organized training, have tutorials available, and interdepartmental support. Figure 5 emphasizes the challenges that have been reported and their prevalence in AI-assisted projects. Another major constraint is high material cost which is reported by 22 respondents (31%). Large-scale experimentation and equitable access by students has not been possible because many smart materials are currently costly like shape memory alloys or advanced polymers. This issue highlights the necessity of institutional investment or the creation of cost-efficient options. The access to the tool and resources (26%) is another complication as to deal with smart materials, one may need certain fabrication tools, laboratory room or technical material that may not be easily accessible in all programs. Durability of materials (17) is also a source of concern particularly whereby responsive materials fails or becomes useless during repetitive use.

7. Conclusion

The research concludes that the sculptural education using smart materials is a drastic step on bridging the artistic and technological divide. As it is demonstrated in the paper, the variety of responsive materials, including kinetic, sensory, and environmentally adaptive, expand the spectrum of conceptual and practical possibilities in the hands of students and make them rethink sculpture as a dynamic, interactive medium. The findings highlight how smart materials could be utilized to get curiosity, stimulate experimentation, and interdisciplinary group work, thus allowing learners to obtain those skills that might be transferred to contemporary creative practice. Despite such positive results, there are also critical issues that are pointed out during the study. Technical limitations, money, and necessity of specific knowledge can limit the access to students and influence the results of the project. These issues confirm that much is to think over in preparing the curriculum, introducing more institutional aids, as well as developing fair teaching strategies that would result in the smart material technologies being made available to students of all abilities. The problem of sustainability should be also mentioned as teachers and learners are to consider material lifecycle, environmental impact, and sustainable usage of new technologies. This will enable schools to create not only the makers but also the critical thinker who is capable of negotiating complex relations between art and technology on the one hand and the environment on the other. This prepares the students to contribute in the emerging fields of interactive art, digital fabrication and adaptive design.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Ding, Y. (2021). The Application of Polymer Materials in Interior Decoration and

Design. Synthetic Materials Aging and Applications, 50(2), 142–161.

Du, J. (2022). Application of a New Type of Composite FRP in Modern Sculpture art

design. Adhesion, 49(2), 51–54.

Guo, S. (2025). Emotional expression in Artworks and Psychological Reactions of

Audiences. Journal of Art, Culture and Philosophy Studies, 1(1).

Liu, C., Zhang, L., Ren, Y., &

Zhang, J. (2021). Review on Effect of Non-Metallic

Inclusions on Pitting Corrosion Resistance of Stainless Steel. Journal of Iron

and Steel Research, 33(9), 1040–1051.

Liu, L., Ding, F., & Li, Y. (2022). Big Data Research on Polymer Materials: Common basis, Progress and Challenges. Acta Polymerica Sinica, 53(5), 564–580.

Oladele, I. O., Omotosho, T. F., & Adediran, A. A. (2020). Polymer-Based Composites: An Indispensable Material for Present and Future Applications. International Journal of Polymer Science, 2020, 8834518. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8834518

Peng, J. (2021). Application and Analysis Based on Polymer Materials in Art Painting media. Synthetic Materials Aging and Applications, 50(3), 165–167.

Petti, L., Trillo, C., & Makore, B. N. (2020). Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Development Targets: A Possible Harmonisation? Insights from the European Perspective. Sustainability, 12(3), 926. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030926

Serrao, F., Chirico, A., Gabbiadini, A., Gallace, A., & Gaggioli, A. (2024). Enjoying art: An Evolutionary Perspective on the Esthetic Experience from Emotion Elicitors. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1341122. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1341122

Shi, Y., Chen,

S., Chen, L., Jin, S., & Wu, L. (2021).

Study on Outgassing Characteristics of Epoxy Glass Fiber Reinforced Plastic at

Different Temperatures. Chinese Journal of Vacuum Science and Technology,

41(9), 1039–1045.

Shi, Y., Yu, X., Ban, H., & Peng, Y. (2021). Research and Application on High Performance Structural Steel and its Structural System. Building Structures, 51(5), 145–151.

Stamkou, E. (2022). On the Social Functions of Emotions in Visual Art. Evolutionary Studies in Imaginative Culture, 6(1), 57–60. https://doi.org/10.5325/evoimagcult.6.1.0057

Venkataramanaiah, P., Aradhya, R., & Rajan, J. S. (2021). Investigations on the Effect of Hybrid Carbon Fillers on the Thermal Conductivity of Glass Epoxy Composites. Polymer Composites, 42(2), 618–633. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.25872

Xu, C. (2020). Application of Glass Fiber Materials in Modern Furniture. Packaging

Engineering, 41(12), 345–350.

Yu, T., Sun, D., Wang, Y., &

Geng, Y. (2018). Application of Carbon Fiber

Composite Material in Lightweight Furniture Design. China Forest Products

Industry, 45(2), 50–53.

Zhang, M., Liu, P., & Song, S. (2022). Effects of Preparation Parameters on Microstructure and Relative Density of Copper-Based Composites with Large Particles of Graphite. Chinese Journal of Nonferrous Metals, 32(3), 406–415.

Zhang, Y., Yu, X., & Cheng, Z. (2022). Research on the Application of Synthetic Polymer Materials in Contemporary Public Art. Polymers, 14(6), 1208. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14061208

Zhao, M. (2020). Study on Preparation and Durability of Viscoelastic Tape and Polyurethane FRP. Journal of Functional Materials, 51(12), 9140–9145.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.