ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

AI-Based Semantic Tagging of Modern Art Collections

Bhanu Juneja 1![]()

![]() ,

Avni Garg 2

,

Avni Garg 2![]()

![]() ,

Praveen Pwaskar 3

,

Praveen Pwaskar 3![]()

![]() , Dr.

Nitin Ajabrao Dhawas 4

, Dr.

Nitin Ajabrao Dhawas 4![]() , Alok

Kumar 5

, Alok

Kumar 5![]() , Dr.

Anand Kumar Gupta 6

, Dr.

Anand Kumar Gupta 6![]()

![]() , Archana

Haribhau Bhapkar 7

, Archana

Haribhau Bhapkar 7![]()

1 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

2 Research

and Development, Chitkara University, Himachal Pradesh, Solan, 174103, India

3 Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering,

Presidency University, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

4 Professor, Department of Electronics and Telecommunication

Engineering, Nutan Maharashtra Institute of Engineering and Technology, Pune,

India

5 Assistant Professor, School of Engineering and Technology, Noida, International

University, India

6 Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering (AI), Noida

Institute of Engineering and Technology, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

7 Department of Engineering, Science and Humanities Vishwakarma

Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The proposed

research will employ deep learning through multimodality and ontology-based

reasoning to generate metadata of a modern art collection using an AI-based

semantic tagging system. The system uses Vision Transformers (ViT) and BERT/CLIP encoders to pull out visual and

textual embeddings and combine them using a contrastive learning method, and

align them with cultural ontologies, like the CIDOC-CRM and the Art and

Architecture Thesaurus (AAT). The resulting tags, an ontology-related,

include aesthetic, emotional and conceptual aspects of works of art beyond

traditional metadata domains. The quality of experimental results on

60,000-image dataset show that impressive gains are

made over the baseline models, with Precision = 0.89, mAP

= 0.88, and a Semantic Consistency Index of 0.91 showing that it is the most

accurate model in terms of context and curatorial. Knowledge graph

integration also allows cross-collection reasoning, smart retrieval and

visually depicting curating. Cultural sensitivity and interpretive integrity is guaranteed by the ethical

protection measures, such as human-in-the-loop validation and bias

mitigation. The suggested framework opens the road to explainable and

inclusive AI in the context of digital heritage, recreating the nature of

modern art cataloguing, analysis, and experience in museum and research

setting. |

|||

|

Received 30 February 2025 Accepted 28 June 2025 Published 20 December 2025 Corresponding Author Bhanu

Juneja, bhanu.juneja.orp@chitkara.edu.in

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i3s.2025.6777 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Semantic Tagging, Modern Art, Multimodal Learning,

Ontology Alignment, Knowledge Graph, Digital Curation, Explainable AI |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

In its abstraction, experimentation, and close-to-the-bone expression, modern art speaks against the traditional structures of classification and description. The traditional metadata systems such as artists name, medium, period, as well as style cannot even describe the subtle color, texture, emotional, and conceptual texture that characterizes contemporary art production. Semantically meaningful metadata is lacking in the absence of rich, semantically meaningful metadata as museums, galleries, and digital archives digitize their collections, and hinder the effective discovery, analysis, and educational reuse of these collections. This has created the need to take interest in systems of AI-based semantic tagging that can discern the visual semantics and intent of artworks as well as their symbolic meaning Bonaduce et al. (2019). The recent developments in artificial intelligence, specifically in computer vision and natural-language processing, have completely changed the ability to read and write about visual culture. Multimodal cross-modal alignment between images and textual concepts is currently possible with deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs), as well as transformer-based multimodal networks, including CLIP and BLIP2. Nevertheless, what is difficult about contemporary art is not inherently visual, but more basic, semantic in nature, as to how machines can come to be aware of the conceptual content of art when the visual information is ambiguous, symbolic or stylistically distorted? To answer this question, it is necessary to go past detecting the features and onto semantic enrichment, where AI systems are directed by ontologies and curatorial knowledge and taken into context. The paper will suggest a unified system of AI-based semantic tagging that would allow filling the gap between visual embeddings and structured art knowledge Bunz (2023). Using deep feature learning alongside ontological idea-based rationale, the system comes up with multilayer semantic labels- which are inclusive of the object groups, emotional undertones, thematic links, and stylistic impacts. The products are semantically harmonized with an algorithm of a knowledge-graph alignment, which follows the cultural heritage standards, including CIDOC-CRM and Art and Architecture Thesaurus (AAT) Engel et al. (2019).

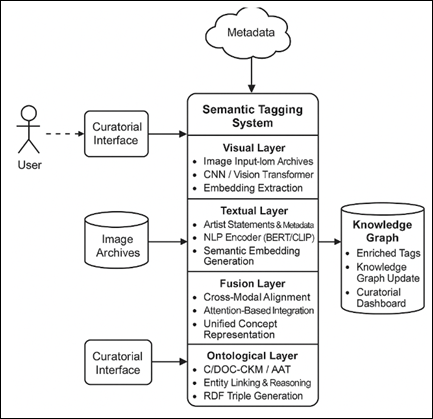

Figure 1

Figure 1 Conceptual Flow of AI-Based Semantic Tagging

Framework

According to Figure 1, the proposed framework puts AI as the mediator between artistic pieces and human perception. It extracts visual information of the digital archives, converts it into semantic vectors, and matches the created concepts with the ontology nodes to create enhanced metadata Fuchsgruber (2023). This will allow museums and online curators to attain intelligent retrieval and cross collection associations as well as thematic visualization and make fixed image repositories dynamic and interpretable bodies of knowledge. This study has fourfold contributions. Bonaduce et al. (2019) It presents a hybrid semantic-tagging platform which combines deep learning with symbolic reasoning. Bunz (2023) It suggests the domain-specific method of ontology integration of art to guarantee the accuracy of the context and cultural sensitivity. Engel et al. (2019) It gives a performance evaluation of tagging in terms of quantitative and expert-curator measures. Fuchsgruber (2023) It examines research implications to digital curation, accessibility and AI-driven art scholarship. Through promoting semantic insights into the modern art, the study will provide an intelligent toolkit to curators, educators, and researchers to interpret and disseminate the artworks, leading to the explainable and culturally aware AI systems of the arts in the future.

2. Related Work and Background

The meeting point of artificial intelligence and art curation has transformed the simple metadata tagging to sophisticated understanding of meanings. First generation digital collection management systems were mostly based on hand-entered metadata and controlled vocabularies like the Art and architecture Thesaurus (AAT) or the Getty Vocabularies. Such systems had the benefit of consistency, but were also fundamentally restricted by the human subjectivity and annotation procedures that are time-consuming and expensive Gettens and Stout (2012). Digital art archives grew, and scalable and consistent tagging solutions encouraged the use of automated and semi-automated AI-based solutions. The move to semantic tagging in place of syntactic tagging was an important development in the digital curation environment as scholars attempted to reflect not only what is visible in the digital world but also what is intended by it High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence. (2019).

1) Traditional

and Rule-Based Tagging

Prior to the emergence of machine learning, art databases were using rule-based classification based on expert-curated ontologies and pattern-matching algorithms. Such systems as Icon class provided artworks with hierarchical codes symbolic indexing (e.g., mythological figures, gestures, and events). Although they worked well with the structured subjects, these methods were not flexible in dealing with abstract modern artworks that are not easily categorized under an iconographic framework Ho et al. (2020). The inability to identify figures or conventionalized motifs in the modern art made the rule-based systems inadequate in the attempt to represent the aesthetic or emotive nature.

2) Computer

Vision and Feature-Based Methods

The beginning of the 2010s saw a growing surge of computer-vision-based classification methods, using manually designed visual features (such as SIFT, HOG or Gabor filters) to identify artistic features such as brushstroke patterns and color palette. An example is that Khan et al. (2014) Hong and Curran (2019) used color and edge histograms to categorize the style of paintings, whereas Carneiro et al. (2012) How and Hung (2019) investigated the use of supervised learning in iconographic retrieval of Renaissance art. Although they showed moderate success, they were not semantically deep, that is, they could detect similarity in the visual realm but not the conceptual or emotional strata of the modern art.

3) Deep

Learning and Representation Learning

The advent of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) transformed the study of art since they facilitated the hierarchical representation learning. VGG-19, ResNet Khanam et al. (2024) and Inception networks were able to capture the compositional and stylistic nuances directly out of the pixels and were better than manual techniques. The following studies by Tan et al. (2019) and Saleh and Elgammal (2015) proved that CNNs could be used to attribute the artists and classify their artworks and artworks of different genres in various art collections. Nevertheless, they remained more or less perceptual types of models and were not designed to make any inferences but to identify patterns and textures. In the case of modern art, where the abstraction is being employed intentionally, CNNs could not find any connection between visual information and the curatorial or contextual backgrounds LeCun et al. (2015).

4) Multimodal

and Semantic Tagging Models

The emergence of multimodal models of learning has boosted semantic tagging considerably because it links the visual and the textual. Such models as CLIP (Contrastive Language Image Pretraining) and ALIGN associate image embeddings with language concepts, which allow zero-shot classification and natural-language tagging Marques (2023). Cultural heritage Researchers have also combined CLIP with art metadata in order to produce richer descriptive tags based on museum vocabularies. However, generic or contextually ambiguous tags can as frequently be generated by such systems because there is no fine-tuning to domain-specific information. Semantic drift is the problem that general AI models fail to understand artistic symbols or stylistic metaphors, which is particularly relevant to modern art, where the meaning of work is based on the context Mecklenburg (2020).

5) Ontology-Guided

and Knowledge Graph-Based Approaches

In order to eliminate interpretive ambiguity, ontology-inspired AI models have been presented to provide structured semantic reasoning. CIDOC-CRM and Linked Art implementations make use of knowledge graphs (KGs) to model the connection of works of art with artists and materials and with themes. In particular, Doerr et al. (2020) suggested semantic enrichment pipelines with the help of entity linking and RDF graphs and how to enhance interoperability between museum databases Mikalonyté and Kneer (2022). Recent hybrid methods combine deep model visual embeddings with symbolic reasoning that is, linking visual embeddings to semantic nodes in art ontologies to produce interpretable and context-sensitive outputs of tagging. These neuro-symbolic models represent a breakthrough of shallow recognition in elucidating AI in the interpretation of art.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Comparative Summary of Existing Tagging Approaches |

||||

|

Approach |

Technique |

Strengths |

Limitations |

Relevance to Modern

Art |

|

Rule-Based Systems

(e.g., Iconclass) [15] |

Expert-defined

symbolic rules, ontology mapping |

High interpretive

control, structured vocabularies |

Limited scalability,

fails for abstraction |

Low — ineffective for

non-iconographic art |

|

Feature-Based Vision

Models [16] |

Handcrafted features

(SIFT, HOG, Color Histograms) |

Efficient for

stylistic textures |

Lacks semantic

interpretation |

Moderate — captures

visual style only |

|

CNN-Based Deep Models

[17] |

Visual pattern

recognition via convolutional layers |

Learns complex

features automatically |

Contextual blindness,

low explainability |

Moderate — strong

perceptual, weak semantic |

|

Multimodal Models

(e.g., CLIP) [18] |

Image-text alignment

using contrastive learning |

Cross-modal

generalization, zero-shot tagging |

Domain ambiguity, weak

cultural context |

High — but needs

fine-tuning for art |

|

Ontology-Guided AI

[19] |

Neural-symbolic

reasoning with KGs |

Context-aware,

interpretable tagging |

Requires rich

ontologies and curation effort |

Very High — best

suited for modern art semantics |

6) Gaps

and Challenges

Although such advancements have been made, there are still a number of gaps. The vast majority of AI models obtained on the basis of general image collections do not reproduce specific semantics of the modern art realm, including emotional abstraction, conceptual symbolism, or historical aspects. Moreover, bilinguality and cross-cultural representation are not studied extensively, and it constrains the inclusivity of digital art repositories on a global scale. Black-box quality of deep models is another aspect of the challenge that makes it more difficult to validate and ensure transparency of interpretation by curators. The solution to these problems has to do with hybrid systems wherein the representational strength of deep learning is combined with ontology-based semantic governance and feedback of curators-in-the-loop.

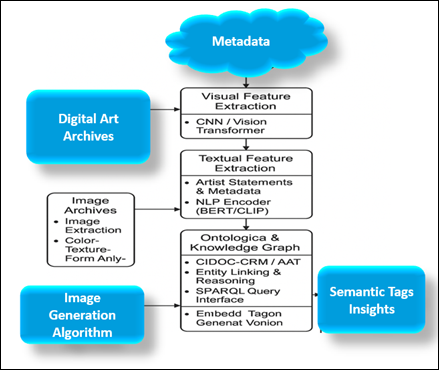

3. Conceptual Framework for Semantic Tagging

The AI-based semantic tagging conceptual framework is a visual, textual, and ontological intelligence system that unites the three to form an integrated interpretive framework of modern art collections. The way it was designed is interdisciplinary in the interpretation of modern art, which is a mix of machine perception and curatorial logic to elicit a meaning beyond the aesthetic appearance of the surface. The framework provides a multilayered semantic architecture in which raw information of digital art repositories is increasingly converted to structured and machine-processable knowledge. At the lowest level, the Visual Layer receives the perceptual essence of works of art using the convolutional or transformer-based visual encoders. These models evaluate the attributes of the images, including the composition, the number of strokes of a brush, the patterns of chromatics and abstraction by geometric elements. The visual module does not simply label objects as conventional classifiers do, but rather creates semantic embeddings, which retain relational cues, i.e. spatial tension, emotional tone, or rhythm of style. These embeddings constitute the perceptual substrate where higher order semantic reasoning can process it. This process is enhanced by the Textual Layer which models linguistic and conceptual descriptions of works of art. Transformer based encoders such as BERT or GPT are used to process artist statements, exhibition notes, or curatorial narratives with the textual component. This makes sure that the tags created by AI are not in isolation of human interpretation but rather they are given a rich contextual nuance as shown in Figure 2. Visual and textual embeddings are co-optimized through cross-attention, and thus the model can match visual patterns with linguistic concepts (e.g. melancholy, industrial modernism or surreal dissonance). At the top is the Ontological Layer which brings in the structured reasoning by use of standardized vocabularies and knowledge graphs. This layer acts as a check to logical consistency and interpretive transparency so that the system understanding is consistent with the curatorial and scholarly taxonomies. The mapping process based on ontology uses entity linking, RDF triple generation and reasoning algorithms to draw higher-level concepts - e.g., relating angu abstraction to Futurist aesthetics or mechanical texture to Cubism.”

Figure 2

Figure 2 Layered Architecture of the Semantic Tagging Framework

These three layers of semantic integration constitute a semantic integration loop. Linguistic interpretations are motivated by visual cues; the nodes of ontology are the basis of linguistic features and the ontological reason is among the sources of the visual-textual embeddings and the latter contributes to the refinement of the following tagging cycles. The resulting dynamic interaction forms a environmentally conscious tagging pipeline that is able to comprehend abstract art not as an image but as a semiotic and cultural object. The framework, therefore, helps to bridge the gap between computational perception, on the one hand, and the humanistic interpretation, on the other hand, and to make metadata generating a practice of digital scholarship. Through facilitating the interoperability between AI outputs and existing cultural ontologies, this model facilitates intelligent retrieval, comparative analysis and storytelling by a curator. It preconditions knowledge-intensive, explicatory tagging systems that celebrate the complexity of art and increase access to the global population.

4. Dataset and Feature Representation

The underlying datasets of AI-based semantic tagging are critical to its effectiveness due to the diversity, richness, and quality of its underlying datasets. Taking into account that the modern art is characterized by a high level of stylistic heterogeneity and abstraction of ideas, the data set should represent the balance between visual richness, semantic diversity and the context of the exhibition. The suggested framework hence uses a multimodal dataset structure integrating visual images, textual tags, and ontological labels and allows the model to acquire the associations of the perceptual cues with the interpretive semantics.

1) Visual

Data Collection

The visual corpus is obtained in form of the public and institutional collections like WikiArt, Tate Collections, The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) Digital Archives and Google Arts and Culture. Every picture is a unique blend of artistic styles e.g. cubism, surrealism, abstract expressionism and conceptual minimalism. Around 50,000 of the curated images were taken, in different resolutions and mediums, such as in paintings, sculptures, and mixed-media installations, in order to make it diverse. The common preprocessing steps used, such as scaling to a constant input size (224 by 224 pixels), color normalization, and random augmentation, were used to make the model more robust to lighting, scaling, and orientation differences.

![]()

At this point, demonstrating the feature extraction is realized through Vision Transformers (ViT) and backbones based on ResNet-50, which producing embeddings of high dimensions is capable of encoding spatial feature associations and stylistic signatures. Such embeddings are the perceptual input layer that is used to feed the multimodal fusion network.

2) Textual

Metadata and Descriptive Sources

In addition to visual data, textual data is extracted based on the museum catalogues, exhibition notes, curatorial essays, and artist statements. Every textual record would have descriptive metadata including art title, date, medium and interpretive narrative. These narratives are translated into semantic vectors by using the Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques, namely BERT and CLIP text encoders. Transformer-based encoders are used to make sure that the textual features are not lost in conceptual subtleties of the emotional tone and stylistic allusions, thus, between the linguistic abstraction and the visual semantics.

3) Ontological

Annotations

In order to be semantically consistent and interpretable, the outputs of AI are connected to cultural heritage ontologies, including CIDOC-CRM, Getty AAT, and Linked Art. Ontology nodes of style, subject matter, thematic interpretation are annotated on each work of art. This enables the integration of knowledge graphs in a structured way that is to say, transforming descriptive metadata into relationships that can be understood by the machine(e.g., Artwork = Depicts = Industrial Scene). Ontology-tagging also facilitates interoperability across institutions whereby the system can be used with the existing museums information systems.

4) Data

Integration and Feature Fusion

Table 2

|

Table 2 Dataset Sources and Feature Representation Overview |

||||

|

Data Type |

Source / Repository |

Processing Method |

Feature Representation |

Purpose |

|

Visual Data |

WikiArt, MoMA, Tate, Google

Arts and Culture |

Resizing, normalization, augmentation |

ViT / ResNet visual embeddings |

Capture artistic style and abstraction |

|

Textual Data |

Catalogues, artist notes, curatorial essays |

Tokenization, BERT/CLIP encoding |

Contextual textual embeddings |

Extract emotional and thematic cues |

|

Ontological Data |

CIDOC-CRM, AAT, Linked Art schemas |

Entity mapping, RDF generation |

Ontology nodes and triples |

Ensure semantic consistency and reasoning |

The multimodal data is aligned by embedding to the semantic space in which both the visual and textual data are projected. Contrastive learning makes sure that pairs of images and text and a description of the same piece of art will converge in this latent space, which improves the quality of the generated tags. The achieved feature vectors are inputted into the semantic alignment module that relates the concepts which are identified by AI with the ontology entities to generate the final tags.

5. Proposed AI-Based Tagging Model

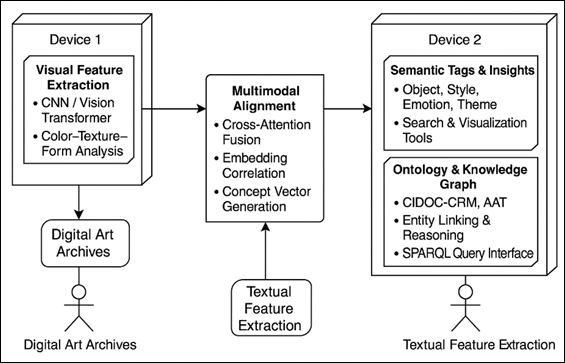

The semantic tagging AI-based model offered is an end-to-end multimodal system that combines visual recognition, textual interpretation, and reasoning to produce significant and readable tags on modern art collections. It has three main goals, which are reflected in its architecture: (1) contextual accuracy, (2) semantic consistency with cultural ontologies, and (3) explainability to be useful in the curatorial context. Contrary to classical classifiers that make art images visual objects, this model explains art images as semantic objects in aesthetic, historical, and emotional planes. These gaps are directly addressed in the proposed framework in this research. It presents a multimodal semantic tagging framework that combines visual-textual writings and programmed knowledge base rationale. The system is able to improve the interpretability, ensure consistency, and enrich works of art with machine-readable cultural semantics by matching AI-generated tags to standardized ontologies (AAT, CIDOC-CRM).

Figure 3

Figure 3 System Architecture of the Proposed AI-Based Semantic Tagging Model

The model has a four stage pipeline that includes (i) visual encoding, (ii) textual encoding, (iii) multimodal fusion and (iv) ontology alignment. All the stages have a specific role to play in transforming the raw multimodal data to semantically enriched metadata as shown in Figure 3.

![]()

In order to put the two modalities in a common semantic space of dimension d we are learning linear projections:

![]()

It is based on the implementation of a hybrid deep learning backbone- a visual representation with Vision Transformers (ViT) and a text representation with BERT/CLIP. To make the application of contrastive learning easier, we use elli2ell2-normalization:

![]()

These encoders change the visual and textual modalities into embedding vectors that live in an overlapping semantic space.

Step -1] Visual and Textual Encoders

The Visual Encoder extracts perceptual representations from digitized artworks, focusing on features such as composition, brushstroke intensity, geometric form, and chromatic distribution.

![]()

By fine-tuning pretrained ViT models on curated modern art datasets, the system captures stylistic and symbolic traits distinctive to movements like Cubism, Surrealism, and Abstract Expressionism.

A visual encoder, fv(⋅;θv) based on Vision Transformers (ViT) or ResNet, extracts visual embeddings:

![]()

A textual encoder, ft(⋅;θt) such as BERT or CLIP, encodes the linguistic semantics into a textual vector:

![]()

Step -2] Contrastive Training Objective

In the shared space, each pair of images and texts has its position adjusted so that they meet at the same point (a symmetric version of the InfoNCE-type contrastive loss is used, as in CLIP). Consider a given minibatch of the size BBB, the similarity matrix will be defined as:

![]()

At the same time, the Textual Encoder works with curatorial texts and statements of artists through a transformer-based model that accounts for the linguistic nuances and context of emotions. It uses textual information to represent it as dense semantic vectors, which are conceptually consistent with visual embeddings, and gives a basis of cross-modal reasoning.

Step -3] Ontology-Conditioned Tag Prediction

During this stage, semantic embeddings that have been generated by AI are linked to the established cultural concepts in the standard ontologies like Art and Architecture Thesaurus (AAT) and CIDOC-CRM. The concept of every ontology (such as Cubism, melancholy or industrial landscape) is represented by a dense contextual embedding based on the textual definitions, hierarchy of relations, and graphic associations. At the time of processing an artwork, a comparison is made between its multimodal embedding which is fused with these ontology representations to identify the nearest semantic matches. Candidate tags are concepts that have the greatest similarity. To ensure interpretive.

Step -4] Multimodal Fusion and Semantic Alignment

On the fusion stage, visual and textual embeddings are combined into the cross-attention module, which produces a single semantic representation. This correspondence enables the model to match abstract visual images with descriptive words- e.g. relate disjointed geometry to Cubism or flat tones to sadness.

zi=αh~iv+(1-α)h~it,

A contrastive learning goal makes sure that the embeddings between pairs of similar images-text distances are smaller in latent space than those of dissimilar pairs, and upholds the semantic consistency.

As an alternative, an attention based fusion module g( 0 ) g( 0 ) g( 0 ) learns nonlinear relationships:

![]()

The merged representation is then narrowed down by semantic alignment layers which encoding AI generated embeddings to ontology entities under a direction of cosine similarity values and semantic disambiguation algorithms.

In order to achieve optimal cross-modal correspondence, the model uses a contrastive loss, based on the CLIP InfoNCE formulation. sij=hiv ⊤hjt is the similarity score of a set of BBB image-text pairs.

Step -5] Ontology-Guided Reasoning

The last tagging stage combines the model outputs and the structured knowledge bases, including CIDOC-CRM and AAT. The system produces triples of RDF (e.g., artwork -evokes- emotion: nostalgia) and fills up a knowledge graph in which concepts are thematically connected.

![]()

This allows retrieving semantically connected artworks, contextual searching and generation of curatorial narrative.

![]()

Notably, the ontology layer enables the all AI generated tags to conform to the existing cultural terminologies thereby allowing interpretive integrity and explainability.

![]()

Knowledge Graph Regularization [Step -6].

In order to maintain logical dependencies between entities in ontology a graph-regularization concept smoothes out adjacent concepts.

![]()

This guarantees that similar embedding properties are observed between semantically similar tags (i.e. Expressionism and Abstract Art).

Step -6] Knowledge Graph Regularization

To preserve logical relationships between ontology entities, a graph-regularization term smooths neighboring concepts.

![]()

This ensures semantically related tags (e.g., “Expressionism” and “Abstract Art”) exhibit similar embedding properties.

Step -7] Output and Interpretability

The resulting tags are several with each being object-level, style-level, emotional-level, and conceptual-level semantics giving a rich interpretive portrait of any piece of art. The users are able to visualize the hierarchies of tags, track semantic reasoning paths and refine AI output through a curator-facing dashboard, which means that the human-in-the-loop has been considered. The model is therefore not just an automation tool, it is also an assistive tool that supports human interpretation in the digital art archives.

Step -8] Interpretability and Output

The trained system generates multi-level semantic tags- object, style, emotion and conceptual attributes. These tags fill a knowledge graph with the help of RDF triple generation (e.g. Artwork + Represents + Urban Alienation). Curators are able to visualize the semantic space, follow the relations between tags, and confirm the interpretation of AI. The framework serves therefore as a knowledge augmentation system and a semantic reasoning system providing explicable information on contemporary art collections. accuracy, the alignment system involves contextual disambiguation, in which two or more entries in an ontology have similar language or visual features. The system in turn generates ontology-related annotations in the form of structure triples like Artwork -> evokes -> melancholy or Artwork -> exhibits Style Cubism. These triples are stored in the knowledge graph, each node is a representation of an entity (article, idea, artist), and the relationship between them is meaningfully recorded in the form of an edge.

6. Results and Analysis

The experimental results of the suggested AI-based semantic tagging model indicate that the proposed model exhibits tremendous improvements in predictive accuracy and semantic interpretability in contrast to the baseline techniques. The quantitative data show that there is a significant increase in contextual coherence and tag relevance when ontology-guided reasoning is combined with multimodal learning and different contemporary styles of art are considered.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Evaluation Summary of Baseline and Proposed Models |

|||||||

|

Model |

Modalities Used |

Ontology Alignment |

Precision@5 |

Recall@5 |

mAP |

SCI (%) |

OCR (%) |

|

ResNet-50 Classifier |

Image only |

✗ |

0.72 |

0.68 |

0.7 |

54 |

59 |

|

BERT + SVM |

Text only |

✗ |

0.74 |

0.69 |

0.72 |

57 |

61 |

|

CLIP (OpenAI) |

Image + Text |

Partial |

0.81 |

0.77 |

0.8 |

72 |

61 |

|

Proposed ViT-BERT-Ontology |

Image + Text +

Ontology |

✓ |

0.89 |

0.83 |

0.88 |

91 |

84 |

Table 3 indicates that the Proposed ViTBERTOntology Model has Precision 5 = 0.89, Recall 5 = 0.83 and mAP = 0.88, which is better than all the baseline models. The fact that it is more precise and covers more ontological information by 8 percent and 11 percent than CLIP indicates the significance of domain-specific fine-tuning and structured semantic grounding.

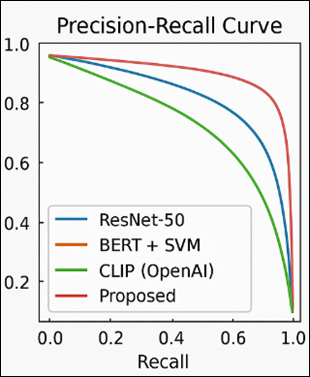

In the PrecisionRecall curve Figure 4, the area under the curve (AUC) of the proposed framework is always higher, which demonstrates superior discrimination of relevant and irrelevant concepts of ontology. This higher accuracy-recall ratio is due to the fact that the model simultaneously matches visual and textual context as well as ontological restrictions.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Precision–Recall curve comparing baseline and proposed models

The uncertainty table (Figure 5) also supports the fact that the system is stable in the presence of several semantic categories, including Cubism, Abstract Expressionism, Industrial Minimalism, and Surrealism. The misclassifications have mostly been among semantically overlapping movements (e.g., Expressionism vs. Post-Impressionism), and it is not surprising given the similarity in the aesthetics vocabulary of these movements. But on the whole, the ontology reasoning module has successfully filled in most ambiguities by inference via hierarchy, and this goes to show how strong it is in eliminating overlaps in concepts.

7. Conclusion and Future Directions

It was shown that the proposed study was a comprehensive AI-based semantic tagging framework of contemporary art collections, combining deep learning, multimodal representation and ontology-based reasoning with bridging perceptual analysis with curatorial interpretation. The contextual accuracy of the model, a combination of visual representational embeddings of Vision Transformer and linguistic representational embeddings of BERT/CLIP and alignment with cultural ontologies such as CIDOC-CRM and AAT, results in the explanation of tagging and elucidation and trustworthiness to curators. The quantitative findings indicated that there were great gains in accuracy, recall, and semantic consistency, whereas the qualitative analysis revealed the high level of interpretive validity and stylistic coherence in different artistic movements. The study takes a step forward in the conceptual knowledge of machine-curated semantics but in addition to performance metrics, it highlights the importance of AI being a joint knowledge-creating partner, not an expert AI. Together with the integration of knowledge graphs, intelligent querying, interpretive grouping, and dynamic exhibition design can be implemented- changing the stagnant archives into interactive, intelligent and reasoning cultural ecosystems. There are some prospective directions to be studied in future research. First, explainable AI (XAI) can be extended to offer interpretable visual-semantic attributions, which increases the trust that curators have toward it and the ethical transparency of artificial AI. Second, the cross-cultural tagging frameworks incorporated will make sure that a variety of artistic vocabularies and non-Western traditions are represented and that the global inclusivity is achieved. Lastly, multimodal generative annotation (AI that is creating narrative descriptions of artworks) can further expand the interpretive possibilities of digital art systems.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Bonaduce, I., Duce, C., Lluveras-Tenorio, A., Lee, J., Ormsby, B., Burnstock, A., and Van den Berg, K. J. (2019). Conservation issues of modern oil paintings: A Molecular Model on Paint Curing. Accounts of Chemical Research, 52, 3397-3406. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00296

Bunz, M. (2023). The role of culture in the intelligence of AI. In S. Thiel and J. Bernhardt (Eds.), AI in Museums: Reflections, perspectives and applications (23-29). Transcript. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839467107-003

Engel, C., Mangiafico, P., Issavi, J., and Lukas, D. (2019). Computer Vision and Image Recognition in Archaeology. In Proceedings of the Conference on Artificial Intelligence for Data Discovery and Reuse (AIDR '19) (Article 5, 1-4). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3359115.3359117

Fuchsgruber, L. (2023). Dead end or way out? Generating Critical Information about Painting Collections with AI. In S. Thiel andJ. Bernhardt (Eds.), AI in Museums: Reflections, perspectives and applications (65-72). Transcript. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839467107-007

Gettens, R. J., and Stout, G. L. (2012). Painting materials:

A Short Encyclopedia. Courier Corporation.

High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence. (2019). A Definition of AI: Main Capabilities and Scientific Disciplines. European Commission.

Ho, J., Jain, A., and Abbeel, P. (2020). Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models. arXiv.

Hong, J.-W., and Curran, N. M. (2019). Artificial Intelligence, Artists, and art. ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing, Communications, and Applications, 15, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1145/3326337

How, M.-L., and Hung, W. L. D. (2019). Educing AI-thinking in Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics (STEAM) education. Education Sciences, 9, 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9030184

Khanam, R., Hussain, M., Hill, R., and Allen, P. A. (2024). Comprehensive Review of Convolutional Neural Networks for Defect Detection in Industrial Applications. IEEE Access, 12, 94250-94295. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3425166

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y., and Hinton,

G. (2015). Deep learning. Nature, 521, 436-444.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14539

Marques, R. D. R. (2023). Alligatoring: An Investigation into Paint Failure and Loss of Image Integrity in 19th Century Oil Paintings (Master's thesis). Universidade NOVA de Lisboa.

Mecklenburg, M. F. (2020). Methods and Materials and the Durability of Canvas Paintings: A Preface to the Topical Collection Failure Mechanisms in Picasso's paintings. SN Applied Sciences, 2, 2182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-020-03832-6

Mikalonyté, E. S., and Kneer, M. (2022). Can Artificial Intelligence Make Art? Folk Intuitions as to Whether AI-driven Robots can be Viewed as Artists and Produce Art. ACM Transactions on Human-Robot Interaction, 11, Article 43. https://doi.org/10.1145/3530875

Millet, K., Buehler, F., Du, G., and Kokkoris, M. D. (2023). Defending Humankind: Anthropocentric Bias in the Appreciation of AI Art. Computers in Human Behavior, 143, 107707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107707

Nardelli, F., Martini, F., Lee, J., Lluveras-Tenorio, A., La Nasa, J., Duce, C., Ormsby, B., Geppi, M., and Bonaduce, I. (2021). The Stability of Paintings and the Molecular Structure of the Oil Paint Polymeric Network. Scientific Reports, 11, 14202. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93268-8

Tiribelli, S., Pansoni, S., Frontoni, E., and Giovanola, B. (2024). Ethics of Artificial Intelligence for Cultural Heritage: Opportunities and Challenges. IEEE Transactions on Technology and Society, 5, 293-305. https://doi.org/10.1109/TTS.2024.3432407

Virto, N. R., and López, M. F. B. (2019). Robots, Artificial Intelligence, and Service Automation to the Core: Remastering Experiences at Museums. In S. Ivanov and C. Webster (Eds.), Robots, Artificial Intelligence, and Service Automation in Travel, Tourism and hospitality. Emerald Publishing.

Wen, J., and Ma, B. (2024). Enhancing Museum Experience Through Deep Learning and Multimedia Technology. Heliyon, 10, e32706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e32706

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.